Abstract

Human butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) is considered a candidate bioscavenger of nerve agents for use in pre- and post-exposure treatment. The presence and functional necessity of complex N-glycans (i.e. sialylated structures) is a challenging issue in respect to its recombinant expression. We aim to produce recombinant BChE (rBChE) in plants with a glycosylation profile that largely resembles the plasma-derived counterpart. rBChE was transiently co-expressed in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana. Site-specific sugar profiling by mass spectrometry of secreted rBChE collected from the intercellular fluid (IF) revealed the presence of mono- and di-sialylated N-glycans, with overall glycosylation profile that is virtually identical to the plasma-derived orthologue. Increase in sialylation content of rBChE was acehived by the over-expression of an additional glycosylation enzyme that generates branched N-glycans, (i.e. GnTIV), which resulted in the production of rBChE decorated with a large fraction of tri-sialylated structures. Sialylated as well as non-sialylated plant-derived rBChE exhibit functional in vitro activity comparable to that of its commercially available equine-derived counterpart. These results demonstrate the ability of plants to generate valuable proteins with designed sialylated glycosylation profiles optimized for therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, the efficient synthesis of carbohydrates present only in minute amounts on the native protein (tri-sialylated N-glycans) facilitates the generation of a product with superior efficacies and/or new therapeutic functions.

Keywords: glycoengineering, recombinant biopharmaceuticals, plants, sialic acid, butyrylcholinesterase

1. Introduction

Organophosphorous pesticides (OP) and chemical warfare nerve agents target acetylcholinesterase, a key enzyme regulating neurotransmission in cholinergic synapses. The high affinity of human cholinesterases to OPs prompted the evaluation of their application for prophylaxis and post-exposure treatment against chemical warfare nerve agents and has met with considerable success in pre-clinical studies [1–4]. In particular, the use of the serum paralog of acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), has proceeded into advanced development and has undergone Phase I clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00333528). BChE was the bioscavenger of choice in these first-in-human studies because it has a long half-life in serum and because it is readily available from outdated blood-banked plasma. However, this is an expensive source of limited supply that cannot meet the expected market demands. Recombinant DNA technology, e.g. mammalian cell-culture or plant-based production systems, could offer a solution to this problem [5, 6]. Despite the promise of such systems in providing the necessary quantities of the bioscavenger, the less-than-optimal pharmacokinetic properties of recombinant human BChE as compared to its plasma-derived counterpart remain a major hurdle [4, 6]. Human serum BChE undergoes post-translational modifications that endow it with a very long circulatory half-life of up to two weeks [7]. Factors that influence the pharmacokinetic profile are mass and glycosylation. In plasma the enzyme circulates as heavily glycosylated tetramer. Each monomer carries sialylated glycans on all of its 9 N-glycosylation sites, increasing its molecular mass from 66 to 85 kDa [8]. Glycan sialylation is crucial for conferring the long circulatory residence time to serum cholinesterase [9, 10].

Human BChE has been recombinantly expressed in various systems [4, 5, 9, 11, 12]. However in most cases this yields a protein with reduced circulatory half-life. For example, BChE expressed in mammary glands of transgenic goats and excreted into their milk is mostly dimeric, bears greatly under-sialylated glycans, and has a half-life of 6.5 h in the guinea pig model [11] as compared to 64.6 h of human plasma-derived BChE [13]. Similarly, recombinant human BChE that was expressed to high-levels in transgenic plants and that was shown to be enzymatically identical to the human enzyme, was only 50 % tetrameric and bore non-sialylated glycans [5]. Consequently, plant-derived human BChE was shown to effectively protect animals against OP challenge, but also have relatively short circulatory residence [4]. Improvement of the pharmacokinetic properties could be achieved by forced-tetramerization of the protein [14], post-purification decoration of the enzyme with polyethylene-glycol [4, 11], or by chemical polysialylation [6]. Nonetheless, these in vitro modifications complicate the production and formulation process and significantly increase its cost. We have hypothesized that an efficient and cost-effective alternative is to adapt the production system to enable its post-translational modification processes to produce proteins that more closely resemble their human counterparts.

Particularly, plant production systems seem highly relevant – not only bearing lower risks of mammalian pathogens, lower cultivation costs, and allowing easier and less-costly scale-up – but also demonstrating an outstanding degree of tolerance to changes in the N-glycosylation pathway. Indeed, several examples of in planta syntheses of complex human-like glycoforms, including sialylation, have been established [15, 16].

In this study we set out to produce rBChE with a glycosylation profile that largely resembles that of the plasma-derived protein. We used plants as our expression system and focused on generating efficiently sialylated glycovariants. The potent magnICON plant-viral-based system was used to transiently express the enzyme in leaves of the model plant N. benthamiana. rBChE derived from the intercellular fluid (IF, secreted fraction) was analyzed by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS). Site-specific sugar profiling showed the presence of complex N-glycans. Moreover, sialylated rBChE, carrying mono-, di-, and tri-sialylated glycans, was obtained by co-expression of BChE with the six mammalian genes required for in planta protein sialylation [17] and N-glycan branching [18]. In addition, differently glycosylated plant-derived rBChE exhibited normal enzymatic activity.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Construction of magnICON vectors

The signal peptide from the barley α-amylase gene for targeting proteins to the secretory pathway was inserted into the TMV based magnICON vector pICH26211 (kindly supplied by V. Klimyuk) resulting in pICHα26211. Dicotyledonous plant-codon optimized cDNA of the human BChE gene [5] was used as template for PCR amplification using primers with flanking BsmBI restriction sites (used primers BChE-F1: 5’-GCACGTCTCAAGGTGAGGATGACATCATCATTGC-3’ and BChE-R1: 5’-GCACGTCTCAAAGCCTAGAGACCCACACAGCTCTCC-3’); the resulting fragment corresponds to the full length protein without its signal peptide. It was cloned into the Zero Blunt® TOPO® vector (Invitrogen®) and the identity was confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. After digestion with BsmBI, the DNA fragment was cloned into the pICHα26211 BsaI sites. The resulting vector pBChE (Fig. 1A) was transformed into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 pMP90 by electroporation.

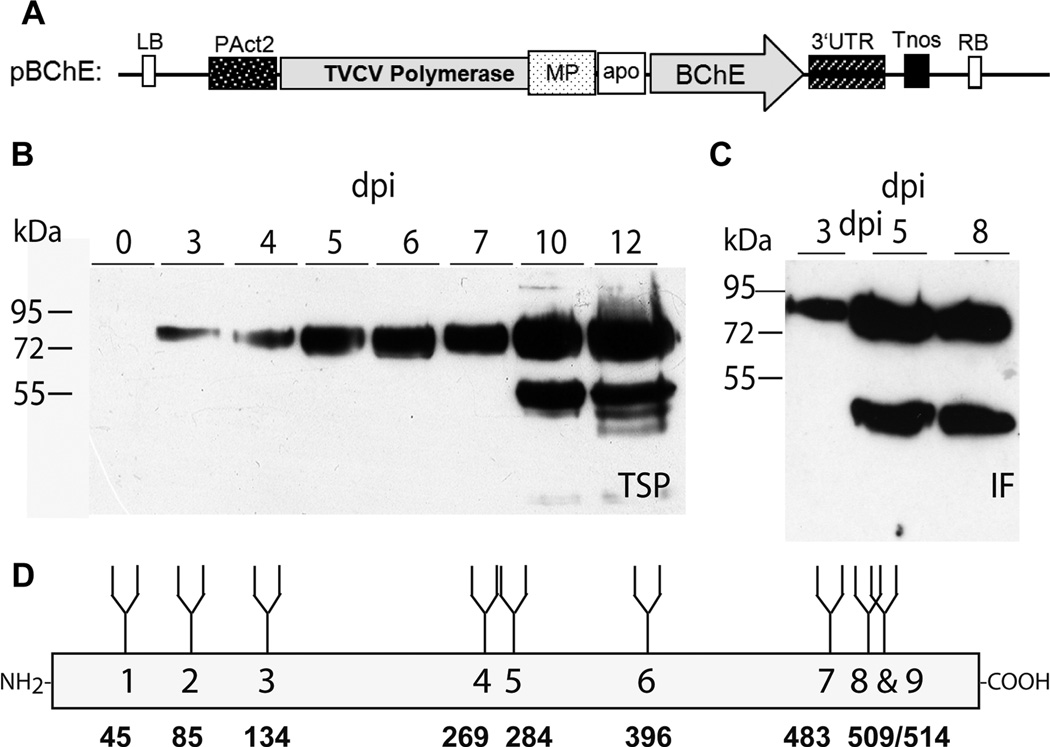

Figure 1.

Expression of human BChE A, Schematic representation of the expression vector and the protein backbone of human BChE. BChE cDNA was cloned into a modified TMV-based magnICON vector (pICHα26211) resulting in pBChE. Apo: Signal peptide sequence from barley α amylase; BChE: Human butyrylcholinesterase sequence lacking the native signal peptide; LB: Left border; MP: Movement protein; PAct2: Arabidopsis thaliana actin 2 promoter; RB: Right border; Tnos: Nopaline synthase gene terminator; TVCV polymerase: Turnip vein clearing virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; 3’UTR: TVCV 3’-untranslated region; B and C, Monitoring of rBChE expression in N. benthamiana. Expression of BChE was analyzed over a period of time ranging from 0–12 dpi. TSP (panel C, 4 µg protein per lane) and IF-derived proteins (panel D, 1µg protein per lane) were fractionated using 10% SDS-PAGE and the proteins were detected using anti-BChE antibodies. Experiments were performed using 4 different leaves transiently expressing BChE and Western blots were done in triplicates. D, Protein backbone of human BChE. Numbers in the box (1–9) refer to the glycopeptides obtained upon trypsin digestion. Bold numbers below the box indicate the positions of the N-glycosylated asparagine residues within the amino acid sequence of the protein.

2.2 Binary vectors for N-glycan engineering

For N-glycoengineering two binary vectors containing the six genes necessary for protein sialylation were used [17, 19]. In addition, a binary vector was generated for over-expression of Arabidopsis thaliana α1,6-mannosyl-β1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (GnTII). cDNA was obtained by RT-PCR with the primer pair Ath-GNTII-12F (5’-TATATCTAGASATGGCAAATCTTTGGAAGAAGC-3’) and Ath-GnTII-14R (5’-TATAGGATCCTCATGGAGATGCACTGCTACTG-3’) as described [20]. The XbaI and BamHI restriction sites created by the primers facilitated the subsequent subcloning of the XbaI/BamHI fragment into the binary expression vector pPT2M [21]. The resulting binary vector (pGnTII) was transformed into agrobacterium strain UIA 143 pMP90. The plasmid containing isoform A of human α1,3-mannosyl-β1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyl-transferase (GnTIV) used in this investigation has been described previously [18]. Detailed information about the expression cassettes used in this investigation is displayed in Supporting Information Table S1.

2.3 Plant material and protein expression

N. benthamiana wild-type (WT) and ΔXT/FT mutant plants, which lack plant-specific β1,2-xylose and core α1,3-fucose residues [22], were cultivated in a growth chamber with a constant temperature of 24°C, 60 % humidity, and a 16h light/ 8h dark photoperiod. 4- to 5-week old plants were used for agroinfiltration [17, 22]. Modifications of the N-glycosylation profile of rBChE was achieved by co-infiltrating binary vectors carrying mammalian genes necessary for protein sialylation [17, 19] and synthesis of tri-antennary N-glycans [18]. Agrobacteria containing magnICON constructs were infiltrated at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1, while binary constructs were mixed at an OD600 of 0.05. The GnTII construct was added to the infiltration mixture at OD600 0.8.

2.4. Isolation of intercellular fluid (IF) and total soluble protein (TSP)

Infiltrated leaves harvested 3–12 days post infiltration (dpi) were submerged in buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA). Vacuum was applied twice for 5 min. The proteins secreted into the apoplast were collected by centrifugation at 900 × g for 15 min (1 leaf yielded approximately 1 mL of IF). Prior to analysis, the IF was concentrated 10-fold with 10 or 30-kDa cut-off Spin-X® UF centrifugal concentrators (Corning®). All steps were carried out at 4°C. Protein quantification was done using the Bradford-based BioRad® Protein Assay following the manufacturer’s instructions. For total soluble protein extraction, infiltrated leaf material (250 mg) was submerged in liquid nitrogen. The material was ground in a swing mill (Retsch®, MM2000) for 2 min at amplitude 60 and then double volume (v/w) of 1×PBS was added. After incubation on ice for 10 min the extracts were centrifuged (6000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C) and the supernatant was stored at -20° C for further analysis. Total soluble protein quantification was done using the Bradford-based BioRad® Protein Assay following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5. Immunoblot analysis and quantification of rBChE

TSP- and IF-derived proteins were mixed with reducing 4× Laemmli buffer, incubated for 5 min at 95°C, and separated by 10 % SDS-PAGE. The fractionated proteins were used for Western blotting and Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 staining. Western blots were analyzed using polyclonal goat anti-BChE antibodies (N-15, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc® sc-46803, diluted 1:300). Detection was performed using HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (polyclonal anti-goat IgG-peroxidase antibody, A5420 Sigma Aldrich®, diluted 1:10000). SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent was used as a substrate (Pierce). BChE expression levels were estimated by a semi-quantitative Western blot analysis using plasma-derived BChE as a standard. Measurements were taken via the BioRad ChemiDoc Imaging System (BioRad).

2.6. Glycopeptide profiling

The N-glycan composition of rBChE was determined using LC-ESI-MS as described [23, 24]. In brief, the samples were submitted to denaturing SDS-PAGE, and the BChE-containing bands were S-alkylated, digested with trypsin, and eluted from the gel fragment with 50 % acetonitrile. Samples were separated on a Biobasic C18 column (150 × 0.32 mm, Thermo Electron) with a gradient of 1–80 % acetonitrile containing 65 mM ammonium formate at pH 3.0. Trypsin digestion allowed the analysis of five of the nine BChE glycopeptides (Gps): Gp2: W80SDIWNATK88; Gp4: N269RTLNLAK276; Gp5: E283NETEIIK290; Gp6: E368NNSIITRK376, and Gp7: D482NYTKAEEILSR493. Glycosites 8 and 9 (Y505GNPNETQNNSTSWPVFK522) are part of the same tryptic peptide. Therefore the discrimination of the glycosylation on the distinct glycosites is arduous, as already observed for hBChE in previous studies [8]. Detection of positive ions was facilitated by a quadrupole-time of flight (Q-TOF) Ultima Global mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The glyco-forms were identified by summed and deconvoluted spectra of the glycopeptides’ elution range. Peaks were labelled according to the ProGlycAn system (www.proglycan.com), with the ProGlycAn translator (http://www.proglycan.com/index.php?page=pga_translator) to convert abbreviations into Consortium for Functional Glycomics (CFG) type cartoons.

2.7. In vitro activity assay of rBChE

BChE activity was determined by a modified Ellman assay [25]. Total soluble protein extracts were analyzed. Hydrolysis of butyrylthiocholine (1 mM, B3253, Sigma Aldrich®) was evaluated in the presence of Ellman’s reagent in sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0) using 96-well microtiter plates. Substrate conversion rates were measured at room temperature with a Wallac® Victor2 plate reader at 405 nm every minute for 20 min, and thereafter at 30, 45, and 60 min. Equine serum-derived BChE (6 units, C1057, Sigma Aldrich®) served as a reference.

3. Results

3.1. Transient expression of BChE in N. benthamiana

The plant-expression optimized cDNA of human BChE was cloned into the TMV-based magnICON vector pICHα26211 (Fig. 1A; pBChE). Agrobacteria carrying the plasmid were delivered to WT N. benthamiana leaves by agroinfiltration. Expression of the recombinant protein (rBChE) was analyzed in time-course experiments using TSP and IF extracted at different days post infiltration (dpi). Western blot analysis of rBChE containing leaf extracts exhibited intensive signals at approximately 85 kDa, the expected size of the full-length monomeric protein. Signals could be detected as early as 3 dpi with increasing intensity up to 12 dpi (Fig. 1B). The expression level was approximately 10.5 µg/g leaf, which corresponds to approximately 1.3 % of TSP (data not shown). Interestingly, at 10 dpi (and beyond), a 55 kDa degradation product was present in addition to the 85 kDa band (Fig. 1B). Degradation was more pronounced in rBChE collected from the IF. Here the degradation product appeared at 5 dpi (Fig. 1C) at an intensity similar to the full-length protein. LC-ESI-MS data (not shown) indicated that the bands ranging from 50 to 55 kDa were in fact truncated rBChE.

3.2. N-glycosylation profiling of plant-derived BChE

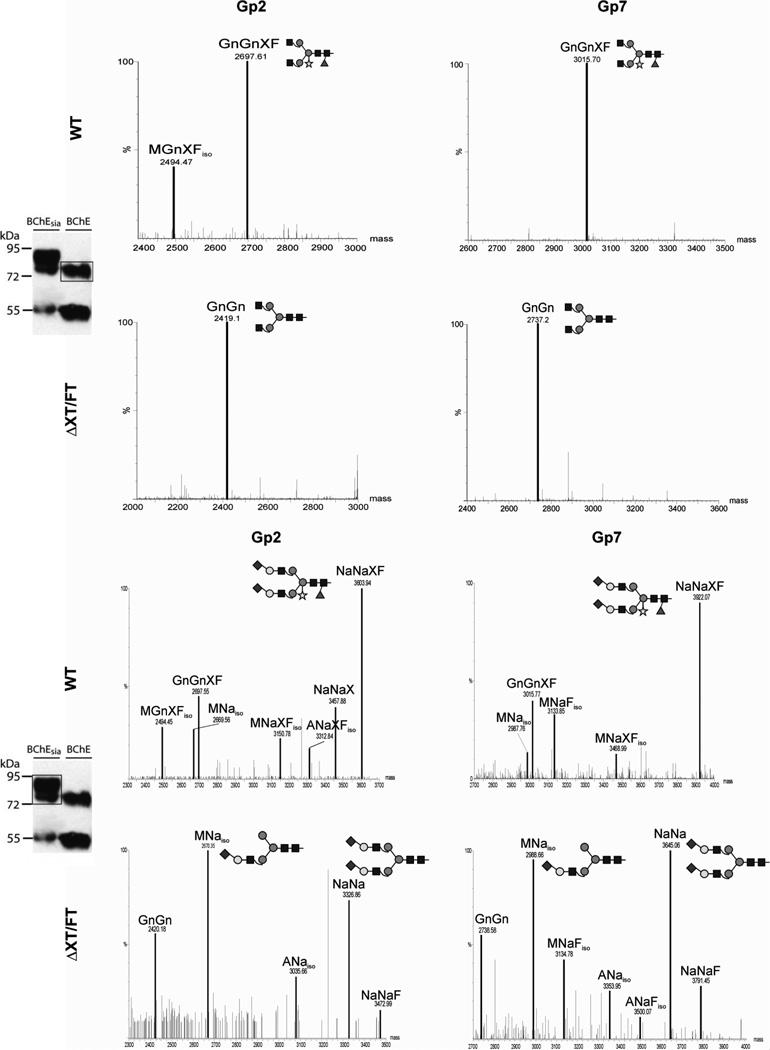

Human serum BChE is a heavily glycosylated 85 kDa protein with nine N-glycosylation sites that are decorated with sialylated N-glycans (Fig. 1D) [6]. The glycosylation profile of secreted rBChE expressed in WT N. benthamiana plants (BChEWT) was determined by LC-ESI-MS analysis. IF-derived BChE-containing bands at 85 and 50 kDa were excised from denaturing gels and digested with trypsin. This allowed for analysis of five of the nine BChE glycosylation sites namely glycopeptides (Gps) 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7, corresponding to the N-glycosites Asn85Asn269Asn284Asn396, and Asn483 (Fig. 1D). Although trypsin digestion allowed for analysis of most of the rBChE glycosites, detection of Gps 1 and 3 was not possible, and Gps 8 and 9 are part of the same tryptic peptide. Figure 2 shows the results for Gp2 and Gp7, which are representative of similar glycosylation patterns observed for other glycosites (data not shown). LC-ESI-MS profiles displayed a single dominant N-glycan, namely GnGnXF, accompanied by incompletely processed MGnXF structures (Fig. 2, panel A; Table 1). These are glyco-forms typical for secreted plant proteins. Plant-specific glycosylation, i.e. core β1,2-xylose and α1,3-fucose, was circumvented by expressing BChE in N. benthamiana ΔXT/FT, a mutant that lacks these two sugar residues [22] (BChEΔXT/FT). BChEΔXT/FT exhibited a single human-like complex N-glycan, i.e. GnGn, devoid of plant-typical core β1,2-xylose and α1,3-fucose residues (Fig. 2, panel A; Table 1). Glycosylation of BChEΔXT/FT was consistent on all glycosites analyzed (data not shown).

Figure 2.

N-Glycan profiles of rBChE glycopeptides Gps 2 and 7 expressed in N. benthamiana wild-type (WT) and the glycosylation mutant ΔXT/FT. A, Mass spectra of IF-derived BChE. B, Mass spectra of IF-derived rBChE co-expressed with genes necessary for in planta sialylation (BChEsia). Western blot analysis of BChEsia (lane 1) and BChE (lane 2) are shown on the left. Protein bands used for glycan analysis are boxed. Mass spectra were generated after liquid-chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS) of glycopeptides (Gp) obtained upon trypsin digestion. Peaks are labeled in accordance with the ProGlycAn system (www.proglycan.com). The suffix “iso” at the end of glycan abbreviations denotes the probable presence of isomers. Major glyco-forms are shown as cartoons, for detailed description of cartoons see Supporting Information, Figure S3. Unassigned peaks are background originating from co-eluting peptides. Figure shows a representative glycoprofiling of BChE expressed in different plants out of an average of four experiments.

Table 1.

Relative abundance in % of major glyco-structures detected on plant-derived BChEa

| Structure | BChE (WT) |

BChE (ΔXT/FT) |

BChEsia (WT) |

BChEsia (ΔXT/FT) |

BChEtrisia (ΔXT/FT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGniso | 7 | ||||

| GnGn | 88 | 9 | |||

| MGnXFiso | 15 | ||||

| GnGnXF | 81 | ||||

| ANaiso | 7 | ||||

| NaNa | 71 | 26 | |||

| NaNaF | 6 | ||||

| NaNaX | 20 | ||||

| NaNaXF | 71 | ||||

| Na[NaNa] | 65 | ||||

| ∑other ≤ 5 % | 4 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 9 |

BChE was collected from intercellular fluid. Letters in brackets indicate the expression host, wild type (WT) or ΔXT/FT plants. ∑other ≤ 5 %: sum of glyco-forms present at levels below 5 %. The glycan structures are assigned using the ProGlycAn nomenclature (www.proglycan.com).

3.3. Sialylation of plant-derived BChE

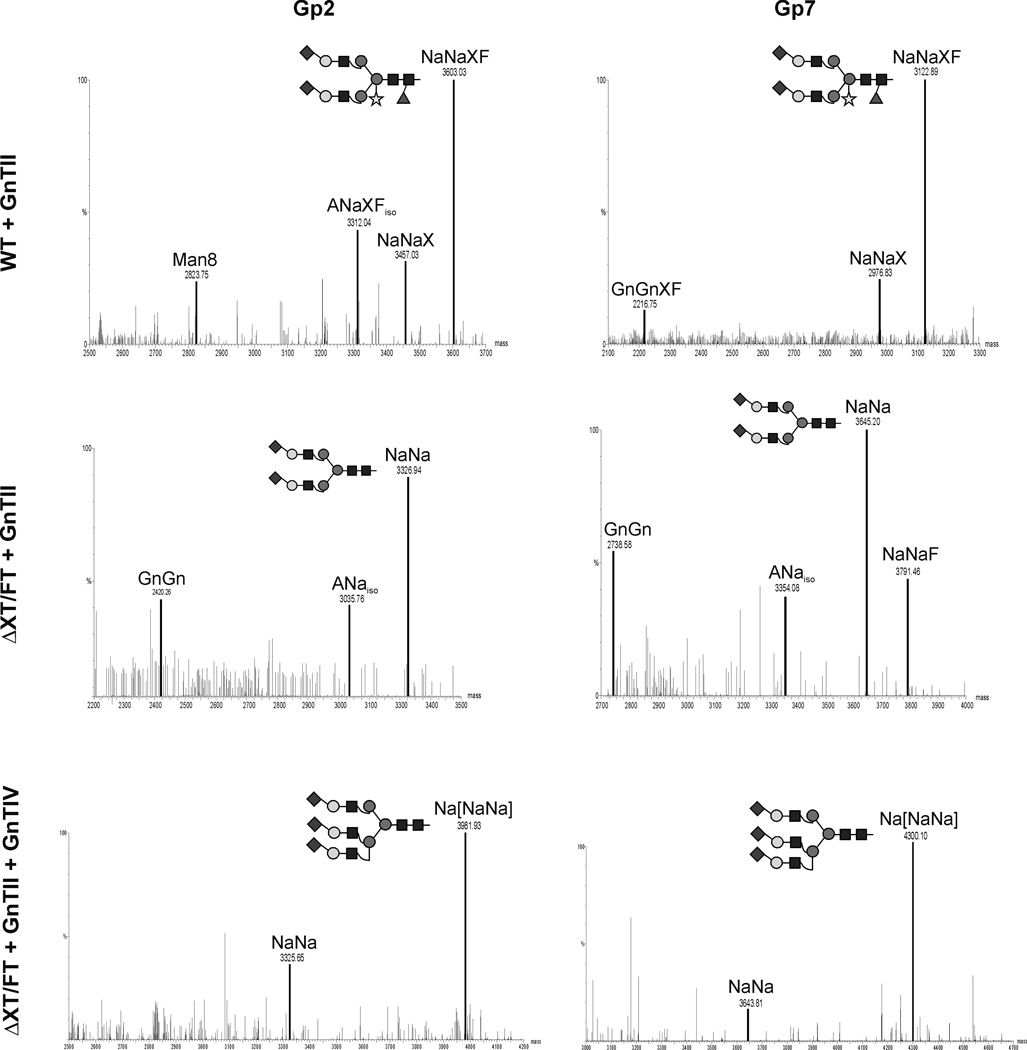

We sought to generate terminal sialylation (BChEsia) to further “humanize” the N-glycosylation of plant-derived BChE. To this end, pBChE was co-infiltrated with the genes necessary for in planta sialylation [17]. Two multi-gene vectors, each carrying three sialylation genes, were used [19]. IF was collected from infiltrated leaves at 5 dpi and subjected to Western blot analysis. A strong signal was obtained for BChEsia at a slightly higher position than BChEWT (Fig. 2). This size shift was most probably due to larger glyco-forms attached to BChEsia. Interestingly, it appears that sialylation improves the stability of BChEsia in the apoplast, as the degradation product is less prominent than in non-sialylated BChEWT (Fig. 2). Glycoprofiles of IF-derived BChEsia expressed in WT plants displayed largely sialylated structures with the major peak representing di-sialylated glycosylation (NaNaXF; Fig. 2, panel B). In addition, incompletely sialylated (MNa, MNaXF, ANaXF) and non-sialylated structures (GnGnXF, MGnXF) were detected (Fig. 2, panel B). (Note, the biosynthetically more plausible isomer is given here and in the following cases). Upon co-expression of rBChE in ΔXT/FT plants together with the genes coding for the sialylation pathway, rBChE carrying efficiently sialylated oligosaccharides, lacking plant-specific xylose and core fucose, was generated. Unexpectedly, the proportion of incompletely processed sialylated MNa structures increased compared to WT plants (Fig. 2, panel B). Incompletely processed N-glycans like MNa possibly result from interference of the transiently introduced enzymes with the endogenous α1,6-mannosyl-β1,2-N-acetylglucosa-minyltransferase (GnTII). To address this issue, Arabidopsis thaliana GnTII was co-expressed with the mammalian genes needed for in planta sialylation. Incompletely processed carbohydrates were then indeed converted into fully processed structures, as seen by the increased appearance of di-sialylated N-glycans (Fig. 3, Table 1 and Supporting Information, Fig. S1). Finally, we aimed to produce BChE with tri-antennary structures to increase levels of sialylation. Thus, we transiently co-expressed BChE with the genes necessary for in planta sialylation together with GnTII as well as GnTIV. The latter is responsible for the synthesis of tri-antennary glycans [18, 26]. In total nine foreign genes were simultaneously delivered into plant cells. Glycoprofiles of BChE expressed in this manner in ΔXT/FT plants (BChEtrisia) showed that tri-antennary sialylation could be achieved in a largely homogeneous manner (Na[NaNa], Fig. 3; Table 1) in addition to di-sialylated glycans. Again, all glycopeptides analyzed showed similar profiles (Supporting Information, Fig. S2). Overall, 80–90 % of BChE N-glycans carried sialic acid moieties upon co-expression of the sialylation pathway, irrespective of the expression host (WT and ΔXT/FT). Notably, small amounts of sialylated structures were also fucosylated (NaNaF) in some samples. Core fucose was most probably present due to incomplete silencing of the α1,3-fucosyltransferase in the ΔXT/FT plants [22]. Importantly, expression of BChE was in no case impaired by the addition of mammalian glycosylation proteins to the infiltration mixture.

Figure 3.

N-Glycan profiles of IF-derived rBChE Gps 2 and 7 co-expressed with genes necessary for in planta sialylation (BChEsia) and N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase II (GnTII). WT (top panel) and ΔXT/FT (middle and bottom panels) plants were used as expression hosts. Bottom panels show the MS profile of IF-derived BChEtrisia obtained upon co-expression of genes for in planta sialyltion, GnTII, and GnTIV (glycosyltransferase responsible for branching). Mass spectra were generated after liquid-chromatography-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS) of glycopeptides (Gp) obtained upon trypsin digestion. The suffix “iso” at the end of glycan abbreviations denotes the probable presence of isomers. Major glyco-forms are shown as cartoons, for detailed description of cartoons see Supporting Information, Figure S3. Unassigned peaks are background originating from co-eluting peptides. Figure shows a representative glycoprofiling of BChE expressed in different plants out of an average of four experiments.

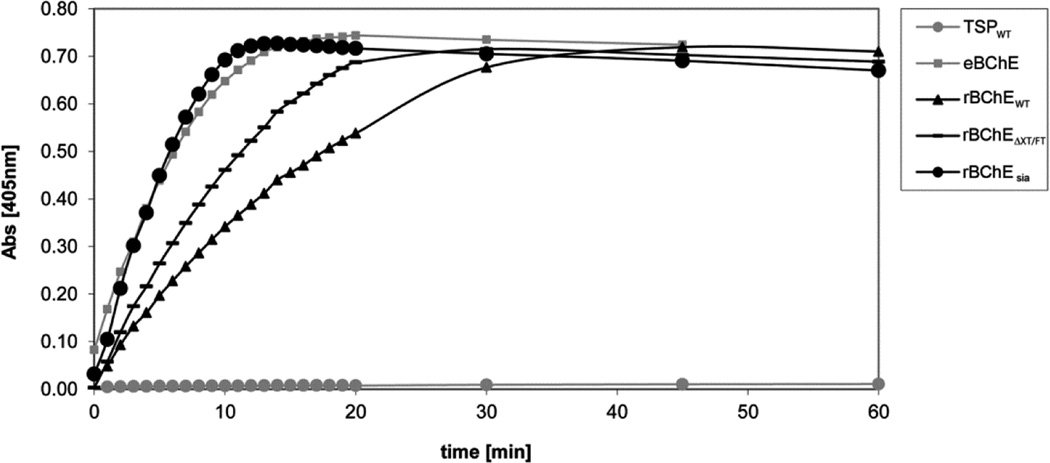

3.4. In vitro activity

The enzymatic activity of plant-derived BChE was monitored with a modified Ellman assay [25]. TSP extracts were used to assay the enzyme’s ability to hydrolyze the butyrylthiocholine iodide substrate. The following glyco-forms were tested: rBChEWT (GnGnXF), rBChEΔXT/FT (GnGn), and rBChEsia (NaNa) (Fig. 4). The activity was compared with that of commercially available equine BChE. All glyco-forms were active, with the sialylated BChE showing activity most similar to the equine enzyme. That plant-proteins other than BChE hydrolyze the substrate could be excluded, because the TSP of leaves infiltrated with agrobacteria that carried “empty” plasmids did not show activity.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of in vitro activity of plant-derived rBChE by a modified Ellman assay.

Hydrolysis of butyrylthiocholine was evaluated in the presence of Ellman’s reagent in sodium phosphate buffer. Substrate conversion rates were measured at different time points. Equine serum-derived BChE served as a reference. TSPWT: TSP of wild-type plants infiltrated with agrobacteria that do not carry the BChE cDNA; eBChE: equine BChE; BChEWT: BChE expressed in WT plants (main glyco-form GnGnXF); BChEΔXT/FT: BChE expressed in ΔXT/FT plants (main glyco-form GnGn); BChEsia: BChE co-expressed with the genes for in planta sialylation in ΔXT/FT plants (main glyco-form NaNa). All samples were analyzed in triplicates.

4. Discussion

In this study, we set out to produce rBChE in plants with a glycosylation profile that largely resembles the sialylated plasma-derived counterpart. Moreover we pursued novel in vivo glycoengineering strategies to generate glyco-forms with increased sialylation content, which potentially surpass the overall in vivo efficacy of the native counterparts. By using the magnICON-based transient expression system we were able to generate the recombinant protein as early as 3 days after delivery of the expression vectors to the model plant N. benthamiana. This time-efficient procedure clearly provides advantages over the more time-consuming generation of rBChE using other (transgenic) expression platforms.

N-glycosylation analysis of secreted rBChE collected from leaf apoplast (IF-derived) exhibited a largely homogeneous glycosylation profile with a dominant glycoform, either GnGnXF or GnGn, depending on whether the expression host was WT or the glycosylation mutant ΔXT/FT. Although consistent glycosylation is typical for secreted recombinant proteins in plants [15], the presence of virtually only one oligosaccharide structure, as was the case for BChEΔXT/FT, is impressive. Such uniformity was not previously demonstrated in any other expression platform and provides a perfect starting point for further elongation steps. Upon co-expression of rBChE with the six mammalian genes responsible for protein sialylation, rBChE was decorated with mono- and di-sialylated N-glycans. This carbohydrate profile largely resembles that of plasma-derived BChE [8]. Although tri-sialylated oligosaccharides are present only in minute amounts on plasma-derived BChE, we aimed to extend rBChE N-glycans toward tri-sialylated structures. Increased sialic acid content has been reported to prolong half-life of recombinant BChE and other bio-therapeutics [6, 27]. By overexpressing an additional glycosylation enzyme that carries out N-glycan branching (i.e. GnTIV), we were able to produce rBChE decorated with surprisingly high amounts of tri-sialylated carbohydrates (70 %). Overall, sialylated structures of IF-derived rBChE accounted for up to 90 % of all glycans detected in the sialylation experiments aimed at di- and tri-sialylation (Table 1). Such glyco-engineered BChE holds great promise for therapeutic applications. Here we demonstrated by the use of a modified Ellman assay that the three plant-derived glyco-forms (BChEWT, BChEΔXT/FT, and BChEsia) are biologically active. The activity profile of BChEsia largely resembles that of the commercially available equine-derived protein.

During our studies we had to overcome unexpected obstacles, like the appearance of significant amounts of incompletely processed structures (MNa). On IF-derived BChEWT and BChEΔXT/FT such hybrid carbohydrates (MGnXF, MGn) are present in only small amounts, if at all. Thus it appears that the simultaneous transient expression of “foreign” glycosyltransferases, which are required for in planta sialylation, impairs the functions of endogenous enzymes. From the structures synthesized (MNa) it seemed obvious that this was the case for GnTII. This enzyme generates important intermediate structures for complete processing to complex sructures, such as GnGnXF and GnGn, which are required as acceptor substrates for galactosylation and subsequent sialylation. Indeed, by transiently over-expressing GnTII we were able to convert the incomplete structures into fully processed sialylated BChE glyco-forms (NaNa, NaNaXF). It seems that apart from supplying the six genes necessary for in planta protein sialylation [17], some fine-tuning is needed for the generation of tailor-made structures. Such fine-tuning is not predictable a priori, it largely depends on the N-glycan structure required and the protein itself. Basically, it can be accomplished by altering the mixture of glycosylation enzymes in the agro-infiltration procedures. The expression levels of certain foreign glycosylation enzymes may also interfere with the endogeneous glycosylation machinery. This has for example been observed with the expression of human β1,4-galactosyltransferase, where low expression levels are advantageous [28].

An important aspect of this study is that in planta sialylation can be achieved by the use of multi-gene vectors [19], instead of single gene vectors. Two binary vectors, each carrying three mammalian genes, permitted the synthesis of sialylated rBChE. This had the advantage that fewer recombinant agrobacteria could be used in the agro-infiltration procedure, enhancing the chance of all genes being expressed and delivered simultaneously, and thus allowing batch-to-batch consistency of glycosylation. Our results point to the feasibility of creating a single multi-gene vector for the entire sialylation pathway. This further facilitates glyco-engineering by transient expression at large scale as needed, for example, for in vivo studies. Such procedures provide a viable alternative to transgenic plants, which have the disadvantage of time intensive processes and restricted availability.

Another undesired issue we faced was partial proteolytic degradation of the recombinant enzyme, predominantly in the apoplast. Proteolytic attack on recombinant proteins in plants is well known [19, 29, 30]. Secreted proteins are particularly affected, most probably due to the abundant presence of proteases in the extracellular space [31]. Various strategies, like co-expression of proteinase inhibitors and downregulation/elimination of endogenous proteinases, have been reported as suitable approaches to circumvent this unwanted effect [32].

The results presented here are encouraging for generating recombinant BChE suitable for therapeutic application with a pharmacokinetic profile equivalent if not superior (through enhanced sialylation content) to that of the human plasma-derived counterpart. It appears entirely feasible that this proof of concept study will translate into a pharmaceutically valuable product as the procedure described here allows rapid up- and down-scaling under conditions that accord with Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMPs). Animal in vivo studies, which are envisaged in the near future, will be the next important step toward this aim.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Hackl, Department of Applied Genetics and Cell Biology, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Austria for excellent technical support and Elise Langdon-Neuner for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) Laura Bassi Centres of Expertise (Number 822757, to H. S.), the Austrian Science Fund (FWF; Grant Number L575-B13, to H.S.), and the PhD program “BioToP-Biomolecular Technology of Proteins” from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) Project W1224-B09 (to L. N.). This work was funded in part by a National Institute of Drug Abuse Avant-Garde grant (1 P1 DA031340-01) to the Mayo Clinic, subcontracted to TSM and also by the National Institutes of Health CounterACT Program through the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke under the U-54-NSO58183-01 award – a consortium grant awarded to USAMRICD and contracted to TSM under the research cooperative agreement number W81XWH-07-2-0023.

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.

Abbreviations

- ΔXT/FT

xylosyl- and fucosyl-transferase knock-down Nicotiana benthamiana

- 3’UTR

TVCV 3’-untranslated region

- A

galactose

- Asn

asparagine

- BChE

butyrylcholinesterase

- BChEsia

sialylated butyrylcholinesterase

- cDNA

complementary deoxyribonucleic acid

- cGMP

current good manufacturing practices

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- dpi

days post infiltration

- F

fucose

- Gn

N-acetylglucosamine

- GnTII

α1,6-mannosyl-β1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase

- GnTIV

α1,3-mannosyl-β1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyl-transferase

- Gp

glycopeptide

- hBChE

human BChE

- IF

intercellular fluid

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- kDa

kilo Dalton

- LB

left border

- LC-ESI-MS

liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry

- M

mannose

- MP

movement protein

- Na

N-Acetylneuraminic acid

- OD600

optical density at 600 nm

- OP

organophosphate

- PAct2

Arabidopsis thaliana actin 2 promoter

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RB

right border

- rBChE

recombinant butyrylcholinesterase

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TMV

tobacco mosaic virus

- Tnos

nopaline synthase gene terminator

- TSP

total soluble protein

- TVCV polymerase

Turnip vein clearing virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- WT

wild-type

- X

xylose

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no commercial or financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Doctor BP, Saxena A. Bioscavengers for the protection of humans against organophosphate toxicity. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2005:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mumford H, Docx CJ, Price ME, Green AC, et al. Human plasma-derived BuChE as a stoichiometric bioscavenger for treatment of nerve agent poisoning. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2013;203:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mumford H, Troyer JK. Post-exposure therapy with recombinant human BuChE following percutaneous VX challenge in guinea-pigs. Toxicol. Lett. 2011;206:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.05.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geyer BC, Kannan L, Garnaud PE, Broomfield CA, et al. Plant-derived human butyrylcholinesterase, but not an organophosphorous-compound hydrolyzing variant thereof, protects rodents against nerve agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:20251–20256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009021107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geyer BC, Kannan L, Cherni I, Woods RR, et al. Transgenic plants as a source for the bioscavenging enzyme, human butyrylcholinesterase. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2010;8:873–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilyushin DG, Smirnov IV, Belogurov AA, Jr, Dyachenko IA, et al. Chemical polysialylation of human recombinant butyrylcholinesterase delivers a long-acting bioscavenger for nerve agents in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:1243–1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211118110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li H, Schopfer LM, Masson P, Lockridge O. Lamellipodin proline rich peptides associated with native plasma butyrylcholinesterase tetramers. Biochem. J. 2008;411:425–432. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolarich D, Weber A, Pabst M, Stadlmann J, et al. Glycoproteomic characterization of butyrylcholinesterase from human plasma. Proteomics. 2008;8:254–263. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saxena A, Ashani Y, Raveh L, Stevenson D, et al. Role of oligosaccharides in the pharmacokinetics of tissue-derived and genetically engineered cholinesterases. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:112–122. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kronman C, Chitlaru T, Elhanany E, Velan B, Shafferman A. Hierarchy of post-translational modifications involved in the circulatory longevity of glycoproteins. Demonstration of concerted contributions of glycan sialylation and subunit assembly to the pharmacokinetic behavior of bovine acetylcholinesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:29488–29502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang YJ, Huang Y, Baldassarre H, Wang B, et al. Recombinant human butyrylcholinesterase from milk of transgenic animals to protect against organophosphate poisoning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:13603–13608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702756104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Ip DT, Lin HQ, Liu JM, et al. High-level expression of functional recombinant human butyrylcholinesterase in silkworm larvae by Bac-to-Bac system. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2010;187:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lenz DE, Maxwell DM, Koplovitz I, Clark CR, et al. Protection against soman or VX poisoning by human butyrylcholinesterase in guinea pigs and cynomolgus monkeys. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2005:205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duysen EG, Bartels CF, Lockridge O. Wild-type and A328W mutant human butyrylcholinesterase tetramers expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells have a 16-hour half-life in the circulation and protect mice from cocaine toxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;302:751–758. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castilho A, Steinkellner H. Glyco-engineering in plants to produce human-like N-glycan structures. Biotechnol. J. 2012;7:1088–1098. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bosch D, Castilho A, Loos A, Schots A, Steinkellner H. N-Glycosylation of plant-produced recombinant proteins. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013;19:5503–5512. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319310006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castilho A, Strasser R, Stadlmann J, Grass J, et al. In planta protein sialylation through overexpression of the respective mammalian pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:15923–15930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castilho A, Gattinger P, Grass J, Jez J, et al. N-glycosylation engineering of plants for the biosynthesis of glycoproteins with bisected and branched complex N-glycans. Glycobiology. 2011;21:813–823. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castilho A, Neumann L, Gattinger P, Strasser R, et al. Generation of biologically active multi-sialylated recombinant human EPOFc in plants. PloS One. 2013;8:e54836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strasser R, Steinkellner H, Boren M, Altmann F, et al. Molecular cloning of cDNA encoding N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase II from Arabidopsis thaliana. Glycoconjugate J. 1999;16:787–791. doi: 10.1023/a:1007127815012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strasser R, Stadlmann J, Svoboda B, Altmann F, et al. Molecular basis of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I deficiency in Arabidopsis thaliana plants lacking complex N-glycans. Biochem. J. 2005;387:385–391. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strasser R, Stadlmann J, Schahs M, Stiegler G, et al. Generation of glyco-engineered Nicotiana benthamiana for the production of monoclonal antibodies with a homogeneous human-like N-glycan structure. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2008;6:392–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stadlmann J, Pabst M, Kolarich D, Kunert R, Altmann F. Analysis of immunoglobulin glycosylation by LC-ESI-MS of glycopeptides and oligosaccharides. Proteomics. 2008;8:2858–2871. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pabst M, Chang M, Stadlmann J, Altmann F. Glycan profiles of the 27 N-glycosylation sites of the HIV envelope protein CN54gp140. Biol. Chem. 2012;393:719–730. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr, Feather-Stone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagels B, Van Damme EJ, Pabst M, Callewaert N, Weterings K. Production of complex multiantennary N-glycans in Nicotiana benthamiana plants. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:1103–1112. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.168773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egrie JC, Browne JK. Development and characterization of novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein (NESP) Br. J. Cancer. 2001;84(Suppl 1):3–10. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castilho A, Bohorova N, Grass J, Bohorov O, et al. Rapid high yield production of different glycoforms of Ebola virus monoclonal antibody. PloS One. 2011;6:e26040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lombardi R, Donini M, Villani ME, Brunetti P, et al. Production of different glycosylation variants of the tumour-targeting mAb H10 in Nicotiana benthamiana: influence on expression yield and antibody degradation. Transgenic Res. 2012;21:1005–1021. doi: 10.1007/s11248-012-9587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hehle VK, Paul MJ, Drake PM, Ma JK, van Dolleweerd CJ. Antibody degradation in tobacco plants: a predominantly apoplastic process. BMC Biotechnol. 2011;11:128. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-11-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Hoorn RA. Plant proteases: from phenotypes to molecular mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008;59:191–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schillberg S, Raven N, Fischer R, Twyman RM, Schiermeyer A. Molecular farming of pharmaceutical proteins using plant suspension cell and tissue cultures. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013 doi: 10.2174/1381612811319310008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.