Abstract

Purpose

Approximately 30%higher-grade premalignant oral intraepithelial neoplasia (OIN) lesions will progress to oral cancer. While surgery is the OIN treatment mainstay, many OIN lesions recur which is highly problematic for both surgeons and patients. This clinical trial assessed the chemopreventive efficacy of a natural-product based bioadhesive gel on OIN lesions.

Experimental Design

This placebo-controlled multicenter study investigated the effects of topical application of bioadhesive gels that contained either 10% w/w freeze dried black raspberries (BRB) or an identical formulation devoid of BRB placebo to biopsy-confirmed OIN lesions (0.5 gm × q.i.d., 12 weeks). Baseline evaluative parameters (size, histologic grade, LOH events) were comparable in the randomly assigned BRB (n=22) and placebo (n=18) gel cohorts. Evaluative parameters were: histologic grade, clinical size and loss of heterozygosity (LOH).

Results

Topical application of the BRB gel to OIN lesions resulted in statistically significant reductions in lesional sizes, histologic grades and LOH events. In contrast, placebo gel lesions demonstrated a significant increase in lesional size and no significant effects on histologic grade or LOH events. Collectively, these data strongly support BRB’s chemopreventive impact. A cohort of very BRB-responsive patients-as demonstrated by high therapeutic efficacy-was identified. Corresponding protein profiling studies, which demonstrated higher pretreatment levels of BRB metabolic and keratinocyte differentiation enzymes in BRB-responsive lesions, reinforce the importance of local metabolism and differentiation competency.

Conclusions

Results from this trial substantiate the LOH reductions identified in the pilot BRB gel study and extend therapeutic effects to significant improvements in histologic grade and lesional size.

Keywords: Oral epithelial dysplasia, oral cancer, chemopreventive, clinical trial

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a world-wide health problem and one of the most challenging-to-treat human malignancies (1). This is due to the insidious nature of its early disease, reliance upon surgery as the primary treatment modality, and the difficulty of achieving loco-regional disease control (1, 2). Many OSCC patients die from massive local recurrence or second primary tumors (3, 4). Also, despite treatment innovations like inductive chemotherapy and radiation intensification programs, OSCC survival rates remain among the lowest for solid tumors (4, 5). Those patients fortunate enough to be cured often encounter major esthetic and functional issues with their face and mouth (6).

OSCCs arise from malignant progression of a recognized precursor surface epithelial lesion i.e. oral intraepithelial neoplasia (OIN). While not all premalignant lesions transform, over 30% of the higher grade (moderate to severe) OIN lesions progress to OSCC (7, 8). Furthermore, many OIN lesions recur despite obtaining microscopically clear surgical margins; which is frustrating for both clinician and patient and mandates close follow up and additional biopsies (9). Such OIN recurrences imply persistent mutations in the epithelial stem cells responsible for post-biopsy wound repair and re-enforce the need for novel treatment strategies beyond surgery or laser ablation (9). Identification of effective, non-toxic chemopreventive strategies to induce OIN regression, prevent OIN recurrence or suppress progression to OSCC emerges as an appealing approach for long term OIN management.

Previous OSCC prevention trials have employed a variety of chemopreventive compounds including retinoic acid and its derivatives (10), green tea and associated polyphenols (11), and the COX-2 inhibitor, Celecoxib (12), as well as combination of Celecoxib and the EGFR inhibitor Erlotinib (13). Unfortunately, the majority of these previous studies, which relied on systemic agent administration, resulted in modest to negligible chemopreventive effects (10–12) and induced appreciable toxicities (13).

BRB were selected as the trial chemopreventive due to their success in our previous in vitro and in vivo chemoprevention studies (14, 15) and because of their chemopreventive-rich composition which includes four anthocyanins [the predominant BRB polyphenols which provide appreciable chemopreventive impact (16)], ellagic acid, ferulic acid, coumaric acid, and quercetin, phytosterols in addition to folic acid and selenium (17, 18). Furthermore, local BRB anthocyanin metabolism has the potential to sustain local chemopreventive effects e.g. deglycosylation generates highly active anthocyanidins which subsequently are converted to a more stable chemopreventive i.e. protocatechuic acid that can undergo local enteric recycling (19).

Our pilot clinical trial results showed topical application of a bioadhesive gel that contained 10% w/w freeze dried black raspberries (BRB, 0.5 gm, q.i.d. for 6 weeks, n=20) significantly reduced loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in OIN lesions, modulated epithelial gene expression towards terminal epithelial differentiation, and significantly reduced OIN levels of COX-2 (14, 15). These pilot trial data also revealed appreciable inter-patient variations in BRB gel responsiveness (14, 15). A subsequent study was conducted to characterize intra oral bioactivation and retention of BRB anthocyanins in healthy human volunteers to help elucidate mechanisms attributable for these variations in responsiveness (19). As BRB metabolizing enzymes are primarily distributed in the surface epithelia, OIN lesional keratinocytes are well-positioned to benefit from BRB bioactivation (19). Also, there is extensive inter-donor heterogeneity with regard to epithelial levels of enzymes responsible for BRB bioactivation and local enteric recycling (19). It is therefore logical to speculate that patients with higher levels of BRB bioactivation and local enteric recycling enzymes would derive greater chemopreventive benefit due to sustained levels of BRB chemopreventives at the OIN lesional site. A component of this current study was designed to further investigate this BRB metabolism-therapeutic efficacy question.

The current study expanded upon our pilot study as it was multi-University based (Ohio State, North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) and Louisville), incorporated both a BRB containing and a BRB-devoid (placebo) gel and doubled treatment time (3 months versus six weeks). Therapeutic efficacies of BRB-containing and placebo gels (0.5 gm applied q.i.d. for 3 months) were determined by their effects on: 1) clinical lesional size, 2) OIN histopathologic grade, 3) LOH status at putative tumor suppressor gene loci associated with OIN progression to OSCC [3p14 (FHIT), 9p21 (INK4a/ARF), 9p22 (IFNα) and 17p13 (p53)]. Pretreatment OIN biopsies were used to microscopically confirm a premalignant diagnosis and provide baseline biomarkers. Additional protein profiling assays were conducted to assess the contribution of differentiation and metabolic-local recycling enzymes on BRB gel efficacy. Results from the current study confirm therapeutic efficacy is attributable to the BRB constituents as only the BRB gel treated lesions showed significant therapeutic responses as indicated by improvement in lesional size and histologic grade and reduction of LOH events. In contrast, placebo-gel treated lesions significantly increased in size and did not show significant changes in histologic regression or LOH status over study duration.

Materials and Methods

Berry gel manufacturing

Freshly harvested black raspberries from Strums Berry Farm (Corbett, OR) were immediately freeze-dried and ground into powder at Oregon Freeze Dry Inc (Albany, OR). BRB powder was shipped on dry ice to JR Chemical, LLC (Milford, CT) for gel preparation using Current Good Manufacturing Practices. The BRB gel composition used in this trial was identical to our pilot study (14). The placebo formulation replaced 10% FBR with 10% w/w sucrose and food colorants (FD&C Red #40 and FD&C Blue #1) to provide the matching dark blue-black color. With the exception of sucrose and food colorants, the placebo gel was identical to the 10% FBR gel. The 10% FBR-containing and placebo gels are manufactured by JR Chemical LLC.

Covance Laboratories Inc. (Madison, WI) analyzed the BRB powder. Berry constituents were found to closely replicate (≤ 15%) the component distributions in the pilot gel batch (14). Gel stability and bioburden tests for both the BRB and placebo gels were conducted by Bioscreen Testing Services, Inc. (Torrence CA) at 0, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months, which corresponded to the time frame for gel usage.

Clinical Trial Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Investigational New Drug approval was obtained from the FDA (IND#109774). IRB approvals were obtained from the Institutional Review Boards at all three participating Universities i.e. Ohio State, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and Louisville (Trial registration ID: NCT01192204). Forty adults (See Table 1) were consented for trial participation. Inclusion criteria were microscopically confirmed premalignant oral epithelial lesions, no use of tobacco products for six weeks prior and during the three month study and no previous history of cancer (except for basal cell carcinoma of the skin). Participants were screened prior to entrance into and during (10 to 12 day recall intervals) the trial for no tobacco use compliance via unannounced saliva testing for nicotine (NicAlert™, JANT Pharmacal Corporation, Encino, CA). Trial exclusion criteria were previous or current history of non-basal cell cancer, use of tobacco products, and either a microscopic diagnosis of no premalignant change or oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) in the pretrial biopsy. The National Cancer Institute common toxicity criteria version 4.0 was used. All participants returned to clinic every 10 to 14 days for continued assessment. Used gel tubes were returned and new gels were dispensed.

Table 1.

Cumulative Clinical Trial Data.

| # | Sex | Age | Smoking History |

PVL | Previous Biopsies† |

Lesional

Size (mm2) |

Histopathology |

LOH |

Cumulative Responsiveness (Score) |

3-Month Recurr- ance |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PkYrs (*) | PreTx | PostTx | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | PreTx | PostTx | ||||||||

| Active | A1 | F | 55 | 0 | N | Y (5) | 32.07 | 19.68 | DYS (Mild to moderate) | DYS (Mild) | 3 | 0 | High (5) | Y |

| A2 | F | 62 | 0 | Y | Y (2) | 59.84 | 54.06 | ATY | ATY | 3 | 0 | Intermediate (3) | N | |

| A3 | F | 74 | 26 (1991) | Y | Y (3) | 21.54 | 23.27 | ATY | ATY | 1 | 1 | Non (0) | Y | |

| A4 | M | 69 | 0 | Y | Y (4) | NE | NE | DYS (Focally mild) | DYS (Mild) | 2 | 0 | Low (2) | N | |

| A5 | F | 65 | 0 | N | Y (6) | 8.87 | 6.80 | DYS (Moderate to severe) | DYS (Moderate to severe) | 2 | 1 | Low (1) | N | |

| A6 | M | 56 | 5 (1980) | N | N | 58.18 | 0.00 | DYS (Mild) | Normal | 3 | 0 | High (8) | LC | |

| A7 | F | 55 | 0 | N | Y (4) | 6.78 | 0.00 | DYS (Severe) | DYS (Mild to moderate) | 0 | 0 | High (6) | Y | |

| A8 | F | 69 | 35 (1996) | Y | Y (3) | 30.60 | 33.93 | DYS (Mild) | DYS (Mild) | 1 | 0 | Low (1) | Y | |

| A9 | M | 60 | 20 (1975) | Y | Y (1) | 74.80 | 42.28 | ATY | ATY | 0 | 0 | Low (1) | N | |

| A10 | M | 66 | 5 (1968) | N | Y (1) | 39.64 | 43.07 | DYS (Mild) | DYS (Mild) | 0 | 0 | Non (0) | N | |

| A11 | M | 47 | 0 | Y | N | 170.87 | 72.56 | ATY | ATY | 0 | 0 | Low (2) | N | |

| A12 | F | 59 | 25 (2010) | Y | Y (1) | 24.07 | 10.88 | ATY | ATY | 0 | 0 | Low (2) | N | |

| A13 | F | 70 | 0 | Y | Y (1) | 53.98 | 49.71 | DYS (Mild) | ATY | 0 | 0 | Low (1) | N | |

| A14 | F | 61 | 0 | Y | Y (1) | 63.33 | 106.45 | DYS (Mild) | DYS (Moderate) | 3 | 3 | Low (−4) | N | |

| A15 | F | 73 | 20 (1989) | Y | N | 279.24 | 231.40 | DYS (Mild) | ATY | 1 | 1 | Low (1) | N | |

| A16 | F | 56 | 1.05 (1997) | N | N | 12.15 | 8.82 | DYS (Mild) | ATY, | 0 | 0 | Low (2) | N | |

| A17 | M | 70 | 20 (1996) | N | N | 227.70 | 137.69 | ATY | ATY | 0 | 0 | Low (1) | Y | |

| A18 | F | 56 | 0 | Y | N | 23.85 | 16.99 | DYS (Mild to focally moderate) | DYS (Mild) | 1 | 0 | Intermediate (3) | N | |

| A19 | F | 77 | 0 | Y | Y (1) | 53.28 | 49.44 | ATY | ATY | 3 | 0 | Intermediate (3) | Y | |

| A20 | M | 59 | 5 (2006) | N | Y (3) | 110.71 | 54.60 | ATY | ORT | 1 | 0 | High (4) | N | |

| A21 | F | 44 | 0 | N | Y (1) | 63.37 | 30.05 | DYS (Moderate to focally severe) | DYS (Moderate) | 2 | 2 | Intermediate (3) | N | |

| A22 | F | 65 | 0 | N | Y (1) | 75.06 | 77.99 | DYS (Ulcerated severe) | DYS (Severe) | 4 | 1 | Intermediate (3) | N | |

| Placebo | P1 | M | 78 | 5 (1992) | Y | Y (4) | 25.55 | 46.44 | DYS (Mild to moderate) | DYS (Mild to moderate) | 2 | 3 | Non (−4) | Y |

| P2 | M | 63 | 0 | N | Y (3) | 8.76 | 5.94 | DYS (Moderate to severe) | DYS (Moderate to severe) | 1 | 1 | Low (1) | Y | |

| P3 | M | 60 | 0 | N | Y (1) | 50.49 | 51.38 | DYS (Mild to focally moderate) | DYS (Mild) | 0 | 0 | Low (1) | Y | |

| P4 | F | 59 | 0 | N | Y (1) | 38.47 | 52.79 | ATY | ATY | 3 | 0 | Low (2) | N | |

| P5 | M | 41 | 0 | N | N | 43.98 | 47.11 | DYS (Mild) | DYS (Moderate) | 1 | 0 | Non (−1) | Y | |

| P6 | F | 67 | 0 | N | Y (2) | 95.75 | 123.65 | DYS (Mild to moderate) | DYS (Focally mild) | 1 | 2 | Non (−1) | Y | |

| P7 | M | 58 | 5.71 (1999) | N | N | 9.81 | 10.96 | DYS (Mild) | DYS (Mild) | 0 | 0 | Non (0) | LC | |

| P8 | F | 32 | 7.5 (2011) | Y | Y (8) | 64.43 | 78.80 | DYS (Mild) | DYS (Mild) | 2 | 0 | Low (2) | Y | |

| P9 | F | 65 | 0 | N | Y (4) | 256.69 | 308.77 | DYS (Mild to moderate) | DYS (Mild) | 1 | 2 | Non (0) | N | |

| P10 | M | 46 | 0 | N | N | 68.85 | 41.72 | ATY | ATY | 1 | 0 | Low (2) | N | |

| P11 | M | 66 | 0.75 (1960) | N | Y (1) | NE | NE | ATY | DYS (Moderate) | 2 | 2 | Non (−3) | N | |

| P12 | M | 62 | 20 (1987) | N | Y (1) | 28.78 | 29.83 | DYS (Moderate to severe) | DYS (Mild to moderate) | 0 | 0 | Low (2) | N | |

| P13 | F | 61 | 0 | N | Y (1) | 10.62 | 8.75 | DYS (Mild to moderate) | DYS (Mild to moderate) | 1 | 0 | Low (1) | N | |

| P14 | F | 68 | 0 | N | N | 77.87 | 74.58 | DYS (Mild to focally moderate) | DYS (Mild) | 1 | 0 | Low (2) | N | |

| P15 | F | 50 | 0 | N | Y (2) | 17.39 | 35.18 | DYS (Severe) | DYS (Moderate to severe) | 0 | 0 | Non (−2) | Y | |

| P16 | F | 52 | 0 | N | Y (1) | 47.54 | 47.21 | DYS (Moderate) | DYS (Moderate) | 3 | 2 | Low (1) | N | |

| P17 | F | 39 | 0 | N | Y (1) | 95.45 | 123.13 | DYS (Mild) | ATY | 0 | 0 | Non (0) | N | |

| P18 | M | 71 | 15 (1994) | Y | Y (1) | 107.23 | 167.23 | DYS (Mild) | DYS (Mild) | 0 | 0 | Non (−2) | N | |

Abbreviations: ATY=atypia DYS=dysplasia LC=lost contact NE=not evaluable ORT=orthokeratosis Pk Yrs=pack years PVL=proliferative verrucous leukoplakia

(year) patient quit smoking

Previous biopsies for OIN at lesional treatment site (number of biopsies performed prior to the trial)

Histologic Grading Criteria

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsies were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Photomicrographs were taken using an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Japan) with 10x objective lens and a Nikon DS-Fi1 digital camera (Nikon, Japan) through ImagePro 6.2 software (MediaCybernetics, Bethesda, MD). A 0–8 grade scale (0=normal with or without hyperkeratosis, 1=atypia with crisply defined clinical margins, 2=mild dysplasia, 3=mild-moderate dysplasia, 4=moderate dysplasia, 5=moderate-severe dysplasia, 6=severe dysplasia, 7=carcinoma in-situ, 8=invasive SCC) was used to rank the light microscopic diagnoses. A diagnosis of “hyperkeratosis” alone indicated a benign, reactive change without evidence of premalignant potential. “Atypia” indicated architectural and cytologic alterations that in the clinical setting of an adherent crisply defined white plaque represent early premalignant change. To reduce subjectivity, two board-certified oral and maxillofacial pathologists reached consensus before a final diagnosis was rendered (20). All participating oral pathologists, surgeons and patients were blinded to the patients’ gel assignments.

Assessment of Lesional Clinical Size

Clinical photographs of the participants’ OIN lesions [pretreatment-time 0, week 1 (biopsy follow-up, baseline for subsequent measurements), mid-study (6 weeks), and immediately prior to final biopsy] were taken with a calibrated measuring device (Puritan, Guilford ME) placed parallel to the long axis of the lesion. Acquired clinical images were analyzed using ImagePro 6.2 software (Media Cybernetics, MD). Lesional sizes were normalized to square millimeters (mm2) according to the following formula: lesional size mm2=pixels of lesional area×100/(pixels of 1 centimeter unit on the calibration device in the same image2. The remaining lesional area after the initial biopsy and prior to gel treatment was the pretreatment size. Posttreatment lesional size was the residual lesional area after 3 months gel treatment and just prior to the final biopsy.

Tissue microdissection and DNA isolation

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsies were sectioned at 8µm thickness on PEN membrane slides (Carl Zeiss, Germany). The entire oral epithelia and the corresponding histologically normal connective tissue were independently captured from pre- and posttreatment biopsies using the PALM Microbeam IV laser capture microdissection (LCM) system (Carl Zeiss, Germany) at The OSU Laser Capture Molecular Core. QIAamp DNA Micro kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) was use for DNA extraction.

PCR amplification and Detection of Allelic imbalance

Genomic DNA isolated from the LCM samples was amplified using the predesigned primers with a 5’ fluorescent label on the forward primer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The microsatellite markers selected for LOH analyses and their corresponding loci and associated genes were: 3p14 [D3S1007(VHL), D3S1234 (FHIT)], 9p21 [D9S171, D9S1748(P16/CDKN2A), D9S1751(P16)], 9p22 (IFNα), and 17p13 [D17S786 (P53) and TP53]. 20 µl PCR mixture which contained5 µl of genomic DNA, 2 µl of primer mix (0.5 µM of each primer), 10µl of AmpliTaq Gold 360 master mix (Life Technologies), and 3 µl of nuclease-free water was amplified using a iCycler thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). PCR conditions were: 95°C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 59°C for 30 s, 72°C for 45 s, and a final elongation step of 72°C for 7 min. Fragment analyses were performed at the OSU Plant Microbe Genomics Facility using the Applied Biosystems 3730 sequence analyzer (Foster City, CA). 1µl of PCR product DNA was added to 9µl HiDi (formamide; Applied Biosystems, Inc.) and 0.2µl or 0.4µl (volume dependent upon DNA concentration) GeneScan-500 LIZ Size Standard (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) for analysis. Both automatic and manual (enabled editing) settings for allele identification (GeneMapper® v4.0, Applied Biosystems) were used to analyzed electropherogram data. Peak intensities ≤ 50 RFUs were excluded for being within background. Microsatellite marker peak patterns and allele sizes were established from normal DNA (15). Connective tissue control samples with only one allele were deemed “Not Interpretable” (NI). In several instances, the PCR amplification products in the normal connective tissue for a particular patient/marker combination were inadequate to allow LOH determination and were designated as Not Available (NA). LOH determinations were made using a modification of the protocol established by Canzian et al. (21) as described by Shumway et al. (15), using an increased level of stringency (>50% reduction in peak intensity) to accept the presence of LOH (21). Baseline OINLOH status was determined from the initial biopsy and then compared to LOH status in treated lesional tissue.

Evaluation of differentiation and local enteric recycling enzymes and cornified envelope precursor proteins by immunoblot analyses

Western immunoblotting was conducted as previously described (19). Primary antibodies and dilutions were: transglutaminase 1 (TGase 1, Abcam, ab27000 Cambridge MA, 1:400), loricrin (Abcam, ab85679, 1 µg/ml, involucrin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, sc-21748, 1:200), cytokeratin 10/13 (Santa Cruz, sc-70908,1:200), UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A (UGT1A, Santa Cruz, sc25847,1 to 400), UDP glucose dehydrogenase (UDP-GlcDH, Santa Cruz, sc137057,1:100), pan-cytokeratin (Santa Cruz, sc8018, 1:200). Secondary antibodies were: goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz), goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Positive controls for TGase1 (TGase 293T lysate), involucrin (CCD-1064 cell lysate), loricrin (Hep G2 cell lysate), cytokeratin 10/13 (A-431 whole cell lysate), pancytokeratin (A-431 whole cell lysate),UGT1A (Hep G2 cell lysate), UDP-GlcDH (Hep G2 cell lysate) were all purchased from Santa Cruz. The Kodak 1D3 image analysis software (Kodak, Rochester, NY) was used for densitometery analyses. Results were normalized relative to endogenous pancytokeratin expression because: 1) the enzymes either exclusively (transglutaminase 1) or predominantly reside in surface epithelia (19), 2) cornified envelope proteins are epithelial, and 3) proteins normalized relative to epithelial as opposed to epithelia + connective tissue content of the biopsies. See Supplemental Table S1 for the physiological functions of these selected proteins.

Determination of the overall therapeutic responsiveness

A responsiveness score that incorporated extent of changes in lesional size, histologic grade and LOH was determined for every trial participant. A -3 to 3 responsiveness score scale of lesional size was developed to reflect the extent of change inlesional size. i.e. ≥75% decrease=3, 50%–74% decrease=2, 25–49% decrease=1, 0–24% decrease or increase=0, 25–49% increase= −1, 50% –74% increase= −2, and ≥75% increase= −3. The cumulative responsiveness score was then calculated according to the following formula: Cumulative responsiveness score= Lesional size responsiveness score + Histologic grade responsiveness score (Pretreatment grade – Posttreatment grade) + LOH responsiveness score (Pretreatment events – Posttreatment events). Finally, overall therapeutic responsiveness was categorized in accordance with cumulative scores as follows: 1) High responder≥4, 2) Intermediate responder=3, 3) Low responder=1 or 2, 4) Non-responder≤0.

Statistical Analyses

Two-tailed Mann Whitney U tests were employed to compare pretreatment baseline parameters i.e. size, histologic grade and LOH events in the BRB and placebo gel cohorts. A Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Signed Rank Test was used to compare the pre and post-treatment histologic grades, clinical lesional sizes and LOH events. Cumulative treatment responses (effects on lesional size, histologic grade and LOH events) were evaluated by two-tailed unpaired t test. A Fisher’s Exact Test was used to compare distribution of responsiveness between the BRB and placebo gel treatments. Associations between two therapeutic evaluative parameters were determined by a Spearman Rank Correlation. Relationships among size, histologic grade and LOH used multiple regression analysis. Normality of data determined the use of parametric versus nonparametric analyses.

Results

Patient Demographics and Comparable Pretreatment Baseline Parameters

Forty patients participated in this study. Participants’ ages ranged from 44 to 77 (mean 62.2±1.8) and 32 to 78 (mean 57.7±2.9) in the BRB and placebo gel cohorts, respectively. A majority of the patients never smoked (55% in BRB and 67% placebo gels) and tongue was the most common OIN site in both groups. The gender distribution in the BRB gel cohort was 78.2% (15 women) and 31.8% (7 men) whereas the placebo group was evenly distributed (50% each, 9 women, 9 men) (Table 1). Thirty of the participants had OIN lesions (16 in BRB-72.7% and 14 in the placebo-77.7%) that were recalcitrant to surgery, and had recurred multiple times (2 to 8) at the same site prior to trial participation. Twelve BRB (54.5%) and 3 placebo gel (16.7%) participants had a history of multiple premalignant oral epithelial lesions dispersed throughout their mouth, consistent with a diagnosis of proliferative verrucous leukoplakia (Table 1). No histopathologic evidence of concurrent human papillomavirus infection e.g. koilocytic change in lesional epithelial cells was observed in any of the pre or post treatment lesional tissue biopsies.

Patients in the BRB and placebo gel cohorts had comparable pretreatment ages, clinical lesional sizes, histologic grades, and LOH status. BRB gel patients’ pretreatment lesional sizes (70.95±15.66 mm2n=21) were comparable to Placebo patients’ lesions (61.63±14.39 mm2n=17) (Fig. 1C). One patient in both groups (subjects A4 and P11) had diffuse confluent adherent white plaques that prohibited delineation of a discreetly measurable lesional site. Comparable pretreatment histologic grades were present in both groups [pretreatment BRB group (2.36±0.35, n=22) &pretreatment Placebo group (2.83±0.34, n=18), see Fig. 2C]. Pretreatment LOH events (per patient) for all eight markers were also comparable between BRB gel group (1.36±0.28, n=22) and Placebo gel group (1.06±0.24, n=18) (Fig. 3C). Forty three percent of BRB and 26% of placebo pretreatment lesions demonstrated 9p associated allelic imbalance. The overall pretreatment LOH indices were 27.8% and 21.8%, in the BRB and placebo gels, respectively.

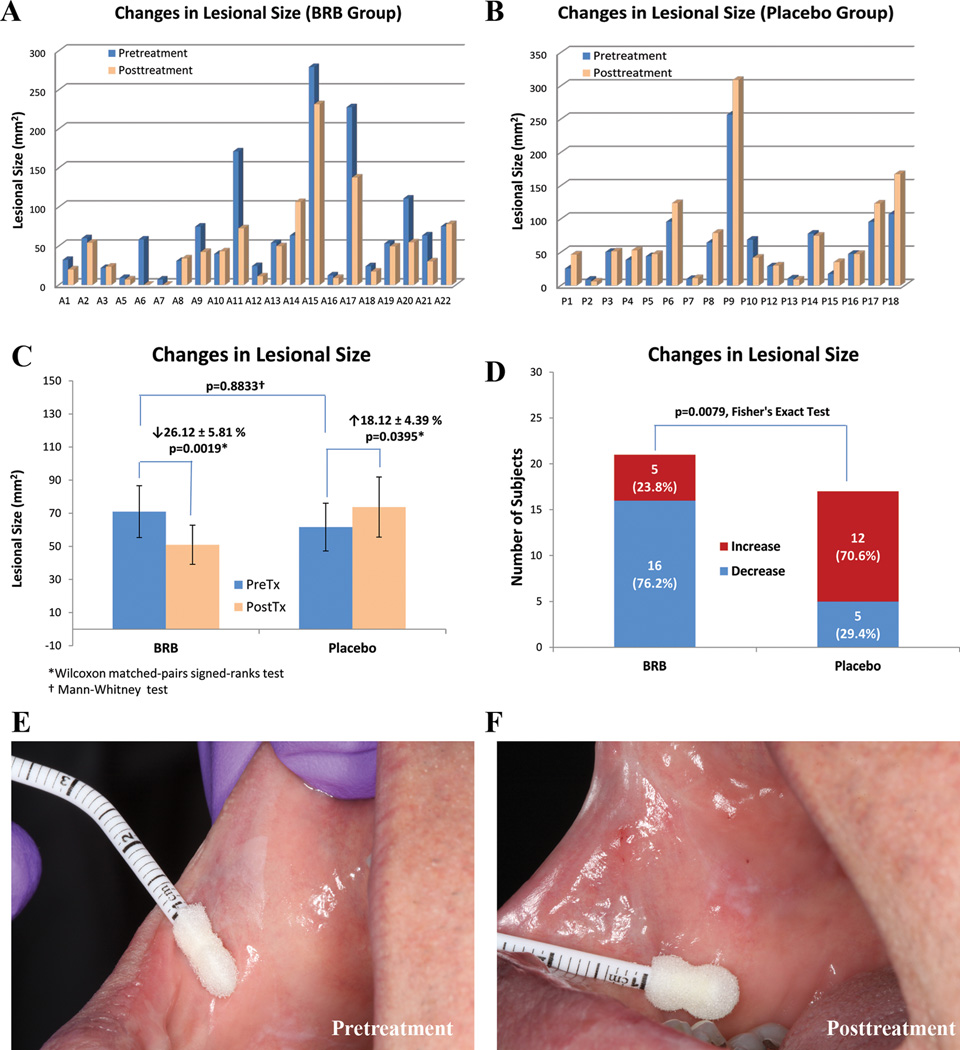

Figure 1.

Effect of gel treatment on lesional size. Histograms A. (BRB gel) and B.(Placebo gel) depict pre- and post-treatment lesional size (mm2) of individual subjects’ OIN lesions. The lesional sizes of subject A4 in BRB group and subject P11 in Placebo group were not included as the extensive distribution and confluent nature of their dysplastic lesions made accurate measurement impossible. C. The mean pretreatment lesional sizes of both groups were statistically comparable. Intragroup pre/post lesional sizes significantly decreased in BRB gel treatment group while significantly increased in Placebo group. D. Intergroup comparison reviewed a significant difference between BRB and Placebo groups. E. This clinical photograph of subject A6 was taken prior to the initial biopsy of the crisply defined rhomboid white plaque close to commissure. The area of the residual lesion remained after initial biopsy was measured as the pretreatment biopsy size. F. Clinical photograph at the same site after 3 months BRB gel treatment and immediately prior to the final biopsy. The remaining lesion had completely regressed and the buccal mucosa at the treatment site had a normal clinical appearance.

Figure 2.

Effect of gel treatment on histologic grade. Histograms A. (BRB gel) and B. (Placebo gel) depict pre- and post-treatment histologic grades of individual subjects’ OIN lesions using the following scale: 0=normal, 1=atypia, 2=mild dysplasia, 3=mild to moderate dysplasia, 4=moderate dysplasia, 5=moderate to severe dysplasia, 6=severe dysplasia. None of the pre- and post- treatment specimens was diagnosed as carcinoma in situ (7) or OSCC (8). C. The baseline histologic grades of both pretreatment groups were statistically comparable. Intragroup pre/post histologic grades significantly decreased in BRB gel treatment group while changes in Placebo group were statistically insignificant. D. Categorization of subjects as per histopathologic responsiveness. E. and F. Photomicrographs of pre- and post- treatment specimens of subject A6 (10x) demonstrated complete histopathologic regression from mild dysplasia (E, pretreatment) to normal epithelium (F, posttreatment). G. and H. pre- and post- treatment photomicrographs of subject A7 (10x) showed partial regression from severe dysplasia (G, pretreatment) to mild to moderate dysplasia (H, posttreatment).

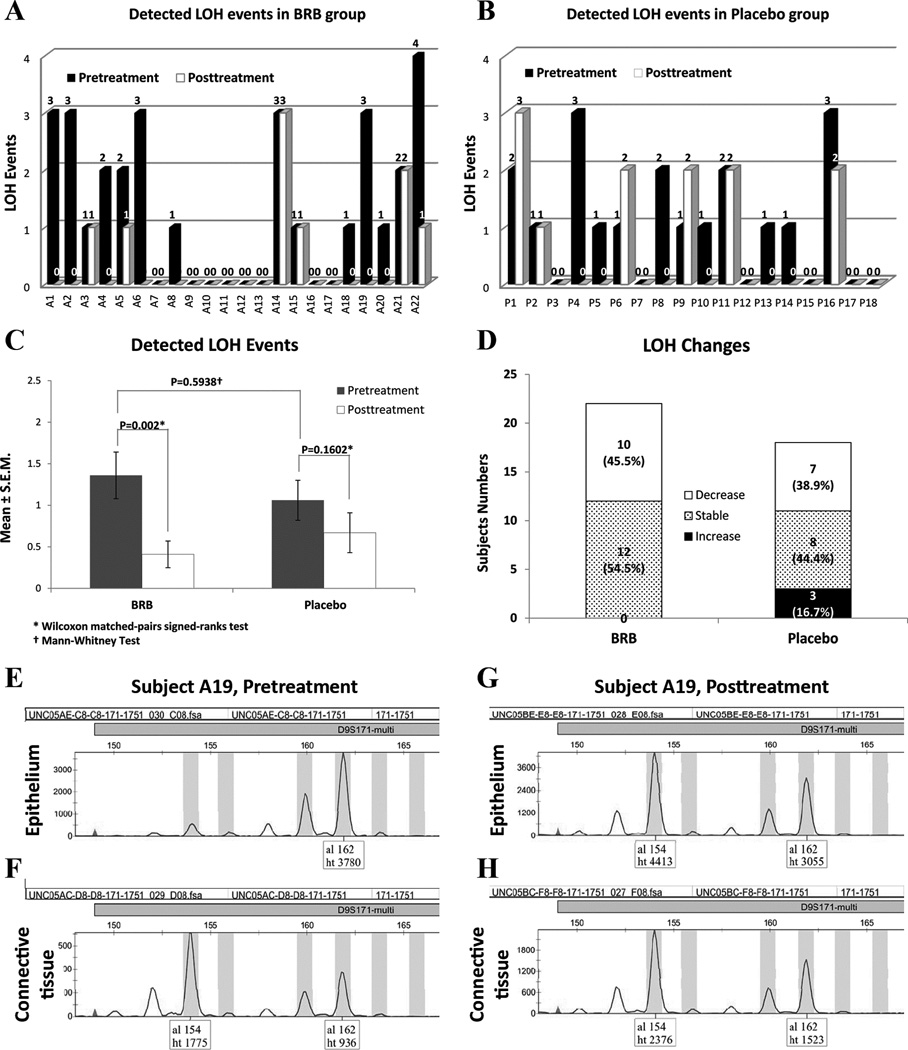

Figure 3.

Effect of gel treatment on loss of heterozygosity (LOH). A. and B. pre- and post-treatment detected LOH events of individual subjects in BRB gel and Placebo gel groups, respectively. C. Intragroup and intergroup statistical analyses. Mean LOH events significantly decreased in BRB gel treatment group while changes in Placebo group were statistically insignificant. The baseline LOH events of both pretreatment groups were statistically comparable. D. classification of subjects as per treatment effects on LOH events. E. and F. Representative genotyping data depict an LOH event occurred on marker D9S171 in subject A19’s pretreatment samples [loss of one allele (al 154) in the epithelium tissue (E), compared to the two alleles (al 154 and al 162) in the patient’s matched normal connective tissue (F)]. G. and H. The lost allele (al 154) of D9S171 was recovered in the epithelial tissue (G) of the same patient after 3 months of BRB gel treatment, and the ratio of peak heights in epithelium (G) was comparable to the connective tissue sample (H).

No deleterious effects were observed in either the BRB gel or placebo gel cohorts and compliance was excellent

While topical application of a gel could result in deleterious effects e.g. contact mucositis or superimposed Candidiasis, no participant experienced any treatment-associated complications. Furthermore, as determined by the minimal residual gel in the returned gel tubes (>95% dose used), patient compliance was high.

BRB gel significantly decreased OIN lesional clinical size

Following 3 months of BRB gel application, 16 of the 21 BRB treated lesions decreased in size (p=0.0019) for an average overall size decrease of 26%. In contrast, 17 of the 19 placebo gel treated lesions increased in clinical lesional size (p=0.0395) with an average increase of 18%. (See Table 1Fig. 1 A, B and C). While none of the placebo gel patients experienced complete lesional regression, two BRB gel patients had 100% lesional resolution. These individuals’ mucosa returned to a clinically (and histologically) normal and healthy appearance (Fig. 1D).

OIN histologic grade was also significantly reduced by BRB gel application while placebo gel had no significant effect

Comparison of the histologic grade of the pretreatment versus post-treatment lesional tissue biopsies demonstrated that application of the BRB gel resulted in a statistical decrease in histopathologic grade (p=0.0488) while placebo gel application did not significantly impact histopathologic grade (p=0.4961) (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Topical application of BRB gel significantly reduced allelic imbalance in OIN lesions

BRB gel treated lesions demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in LOH events at all 9p loci relative to pretreatment parameters p=0.016, n=22. With regard to all loci evaluated, BRB gel treatment significantly reduced overall LOH events, p=0.002, n=22. In contrast, placebo gel application resulted in comparable 9p pre and post-treatment LOH status and did not significantly reduce overall LOH events (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

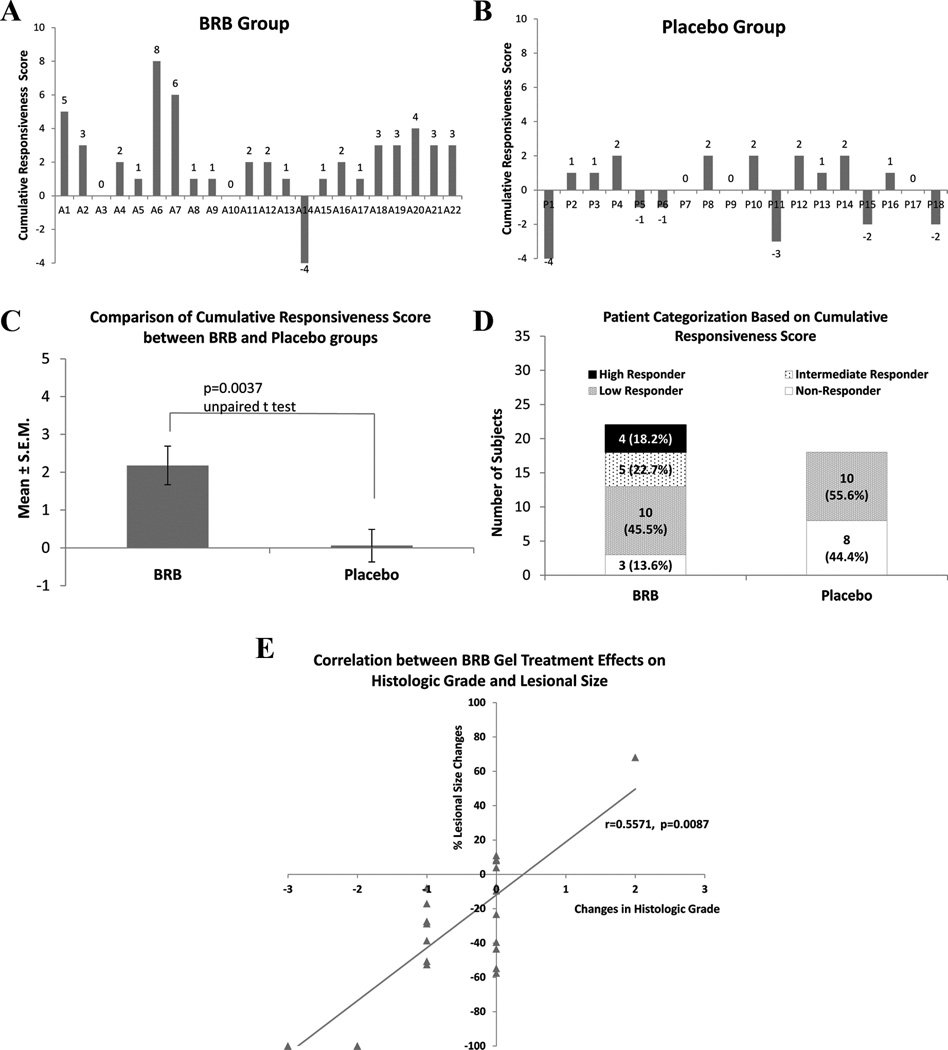

Collective assessment of extent of treatment effects on lesional size, histopathologic grade and LOH events reveals highly BRB-responsive cohort

Cumulative scores, which reflected the extent of gel application effect on lesional size, histologic grade and LOH indices, were assigned for every trial participant (Table 1 and Fig. 4A and B). BRB gel participants had a statistically significant (p=0.004) higher scores, indicative of greater therapeutic effects (Fig. 4C). Nine of the 22 BRB gel participants’ (41%) OIN lesions achieved high to intermediate responsiveness whereas all of the placebo patients were either low (55%) or nonresponders (no therapeutic effects) (Table 1Fig. 4D). Correlative analyses showed a significant association between improvement in histologic grade and reduction in lesional size (p=0.009) in the BRB gel treatment cohort (Fig. 4E). Multivariate analyses of the BRB gel OIN data also revealed a significant relationship among treatment effects on lesional size (identified as outcome), histologic grade and LOH indices (p=0.0001). Consistent with the Spearman Correlation findings, histologic grade made the largest contribution to the multivariate significance. No linear associations or multivariate relationships were detected in the placebo gel data.

Figure 4.

Overall therapeutic responsiveness. A. and B. cumulative responsiveness score of individual subjects in BRB (A) and Placebo (B) groups. The cumulative responsiveness score is defined as the sum of lesional size score (−3 to 3 as per the percent quartile of pre-/post- lesional size changes i.e. 75–100% reduction=3, 50–74% reduction=2, 25–49% reduction=1, 24–0% reduction=0, 0–24% increase=0, 25–49% increase= −1, 50–74% increase= −2, > 75% increase= −3), histologic grade score (pretreatment histologic grade – posttreatment histologic grade) and LOH score (pretreatment LOH events – posttreatment LOH events). C. Comparison of the mean cumulative responsiveness scores between BRB and Placebo groups. D, Categorization of subjects according to their cumulative responsiveness score, where high responder ≥4, intermediate responder=3, low responder=2 or 1, and non-responder ≤0. E. A significant correlation was demonstrated between BRB gel treatment effects on histologic effects and lesional size. No comparable correlation was detected in the placebo gel group.

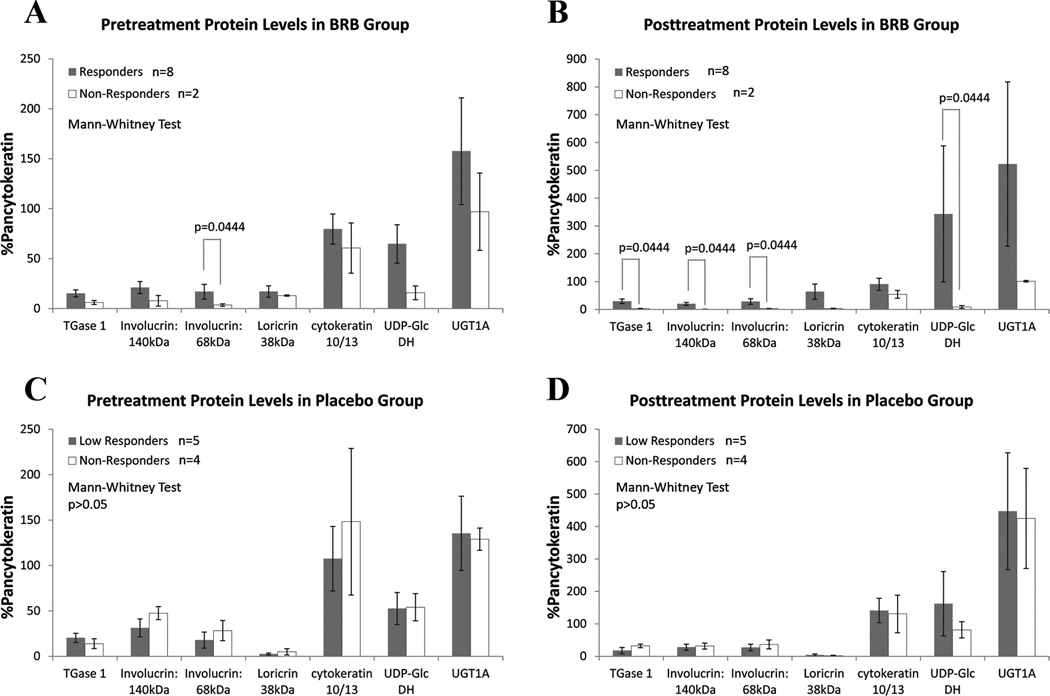

Baseline levels of differentiation and enteric recycling proteins may help identify BRB-responsive OIN lesions

Samples for protein assessment were only available from the larger OIN lesions, resulting in a reduced data set. Baseline intra BRB gel cohort analyses reveals a trend for higher lesional intraepithelial levels of differentiation-associated proteins (TGase 1, involucrin 140 kDa, involucrin 68 kDa, loricrin and cytokeratin 10/13) and enteric recycling enzymes (UGT1A and UDP-Glc DH) in those OIN lesions which responded in a therapeutic fashion to BRB gel application (Fig. 5A and B). No significant associations were identified in the placebo gel cohort. (Fig. 5C and D). Finally, the most BRB gel responsive OIN lesions had the highest pretreatment levels of differentiation-associated proteins (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 5.

Densitometry analyses of Protein Immunoprecipitation studies. Five proteins associated with keratinocyte terminal differentiation (TGase 1, high molecular weight involucrin, low molecular weight involucrin, loricrin, cytokeratin 10/13) and two with BRB metabolism (UDP-Glc dehydrogenase and UGT1A) were evaluated in pre- and post- treatment biopsy samples of those lesions that had adequate tissue. All densitometry results were normalized to the percentage of sample-matched pancytokeratin level, which reflected the proportion of epithelium tissue in each sample. Previous studies have confirmed the epithelial distribution of UDP-Glc dehydrogenase and UGT1(19). Responder and non-responder were defined according to the cumulative responsiveness score (responder≥1, non-responder ≤0). A. and B. pre- and post- treatment protein levels in BRB group. Responders demonstrated a trend of possessing higher level of associated proteins relative to the non-responders. C and D, pre- and post- treatment protein levels in Placebo group. No statistical significance was identified.

Longer-term follow-up reveals OIN lesional recurrence in both cohorts

Thirty eight of the 40 trial patients were available for the requisite three month post trial evaluation; one patient each was lost to follow up in the BRB and placebo gel cohorts. Three months after trial cessation, 6 of 22 BRB and 7 of 17 placebo patients had visible evidence of lesional recurrence at the former treatment sites (Table 1). Only one patient (P6) lesion had a clinically significant lesional recurrence that merited biopsy scheduling at the 3 month recall.

Patients were then returned to their previous oral health care providers for subsequent care. As many of these patients are treated by oral maxillofacial surgeons who use the pathology biopsy services at the trial institutions, longer term follow-up (4 to 31 months post final study biopsy) was available for many trial participants (See Supplemental Table S2). Longer term post-study biopsies were received from 8of the 22 BRB gel and 6 of the 18 placebo gel cohort patients. Two BRB gel cohort patients’ lesions (25%) regressed to non-premalignant states, 4 biopsies remained stable (50%), and 2 lesions progressed (Supplemental Table S2). One of these progressive patients underwent progression of two histologic grades whereas another lesion returned to its pretrial histopathologic grade. Three of the six placebo gel patients’ lesions remained stable, three lesions progressed. Two of the three progressive lesions from the placebo gel cohort increased one histologic grade while the third individual’s lesion (P11) progressed from atypia (pretreatment) to moderate dyplasia (post placebo gel application) to OSCC in the 12 months post trial (Supplemental Table S2).

Discussion

Topical application of a 10% BRB gel resulted in significant reduction in size, histologic grade and LOH events in OIN lesions. The absence of comparable results following placebo gel application strongly supports BRB’s chemopreventive impact and dispels other contributions such as topical stimulation during gel application or hydrogel constituents.

Much of BRB’s chemopreventive effect is derived from the primary phenolic compounds i.e. anthocyanins (16, 22, 23). BRB anthocyanins are redox active compounds which possess both redox scavenging and redox generating properties (24, 25). Accordingly, anthocyanins can quench reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated signaling, reduce adverse DNA-ROS and/or protein-ROS interactions, and inhibit lipid peroxidation (26). Such activities can ultimately suppress inappropriately sustained proliferation and limit DNA and protein perturbations (23, 27). As bulky sugar moieties reduce ROS scavenging capacity, epithelial and oral microflora initiated deglycosylation generates superior antioxidants i.e. the labile aglycones or the more stable protocatechuic acid (28, 29). Anthocyanins also generate ROS (25). At alkalotic pH levels, anthocyanins/anthocyanidins are speculated to form quinones, release superoxide and H2O2, and in the presence of oxidized transition metals, generate the highly mutagenic hydroxyl radical (25). Proximity to anthocyanin-generated superoxide anions and quinone reduction can induce mitochondrial uncoupling, initiate mitochondrial failure and trigger apoptosis (30, 31). Provided the complexity of factors that can modulate BRB chemopreventive impact e.g. metabolism and recycling, pH, presence of reducing equivalents and keratinocyte levels of cytoprotective enzymes, the variability in BRB gel responsiveness observed in this study is understandable (14, 15, 19 and 26).

Lesion regression is one of the most consistently used therapeutic efficacy parameter in human clinical trials (10–12). Placebo gel application resulted in an overall size increase in 70.6% lesions, a finding that is consistent with the proliferative potential of nontreated premalignant oral lesions (32). In contrast, BRB gel application reduced size in 76.2% of OIN lesions. These data compare favorably to previous OIN studies (data expressed as % of lesions which showed a decrease in size) which evaluated: Trial 1) 13cis retinoic acid [0.5 mg/kg P.O.×1 year followed by 0.25 mg/kg P.O.×2 years (48.1%)], or β-carotene + retinyl palmitate [50 mg/d β-carotene + 25,000U/d retinyl palmitate for 3 years (42.9%)], or retinyl palmitate [25,000U/d for long term follow up (20.0%)](10), Trial 2) Celecoxib (100 mg-41.2%, 200 mg-20%, b.i.d. dosing×3 months) (12), and Trial 3) green tea extract [combined green tea extract doses 50%, n=28 (500 mg/m2750 mg/m21000 mg/m2all doses administered t.i.d.×3 months)](11). The corresponding placebo data showed 33% and 18.2% of lesions with size reduction in the Celecoxib and green tea extracts, respectively (11, 12). The cis-retinoic acid study did not include a placebo group. Adverse effects accompanied the systemic administration and included Grade III toxicity with use of 13cis retinoic acid and induction of caffeine-attributable insomnia and anxiety with the higher green tea extract doses (10, 11).

Following BRB gel application 41% of participants achieved a decrease in lesional grade, 4.5% a lesional grade increase and 54.5% retained stable OIN histology. While the 41% grade decrease is identical to our pilot BRB gel trial (14), the percentage of OIN lesions that histologically progressed are 5 fold lower in the current study; findings that likely reflect the doubled treatment time of the current trial (14). A range of histologic responsiveness has been observed in other OIN clinical trials (10–13). The “most responsive” group (13-cis retinoic acid) in the combination 13 cis-retinoic acid, β-carotene and retinyl palmitate trial demonstrated a 30% histologic reduction (10). In the green tea extract study, 33% (3 of 9) obtained histologic regression in the most responsive but toxicity-associated highest dosing group (1,000 mg/m2 t.i.d.), with an overall, a 21.4% rate of histologic regression (6 of 28) (11). The Celecoxib trial did not include histopathologic assessment (12). Recently, the effects of combined administration of Celecoxib (400 mg bid) with escalating doses (50, 75, 100 mg q.d.) of the EGFR inhibitor Erlotinib were assessed on premalignant oral and laryngeal lesions (13). Comparison of baseline histology to final biopsies (obtained at 3, 6 or 12 months) in the 7 evaluable patients showed 43% complete regression (3/7, one laryngeal, two oral lesions), 14% (1/7) partial regression, 29% (2/7) stable disease, and 14% progression (1/7) (13). No placebo group was included (13). Complementary biomarker studies demonstrated significant reduction of EGFR and p-ERK in biopsies that showed histologic improvement (13). Erlotinib dose escalation was accompanied by toxicities including oral mucositis, rash, anemia, sepsis, and elevated liver enzymes; effects that the authors acknowledged as unfavorable for primary chemoprevention (13). Because oral dysplastic lesions have been shown to be less treatment-responsive than oropharyngeal lesions (33), separate reporting of oral and laryngeal lesions appears warranted in more definitive studies (33).

Due to the effects of first pass metabolism and the need for the agent to perfuse from the connective tissue papilla to the avascular epithelia, bioavailability is often challenging for systemically administered OIN chemopreventives (34). Attempts to address the bioavailability challenge by dose escalation are often accompanied by toxicity (11, 13). Furthermore, it is interesting that neither this recent pharmacokinetic study (13) nor any of the previously cited OIN trials determined levels of parent compound(s) and/or metabolites achieved at the treatment site (10–12). Prior to conducting our pilot clinical trial we established that topical BRB gel application provides a pharmacologic advantage at human oral mucosa (35).

LOH-mediated inactivation of one of the two alleles of tumor suppressor genes followed by silencing of the second allele via promoter methylation or point mutation is a putative and probable tumorigenic mechanism (36, 37). Clinical data, which demonstrate a higher risk of malignant transformation in OIN lesions that harbor LOH at tumor suppressor gene loci, support this premise (15, 38). Pretreatment LOH events detected in the current study were lower than those detected in either our pilot trial and in two investigations conducted by Mao et al. (39, 40). These variations likely reflect differences in baseline lesion histology, LOH analytical methods and microsatellite markers evaluated (15, 39, 40). Consistent with previous investigations (15, 37, 39, 40), allelic imbalances in this current study were highest at the 9 p loci. BRB gel treatment significantly reduced allelic imbalances whereas placebo gel did not significantly affect LOH status. To our knowledge, our pilot BRB pilot gel trial (15) and this current study are the only OIN chemoprevention trials to demonstrate a significant reduction in LOH occurrence. We speculate these data reflect removal of LOH harboring keratinocytes from the proliferative pool via BRB-mediated induction of apoptosis and/or differentiation, as previously demonstrated by in vitro studies (31).

Although preliminary, our protein profiling data suggest that BRB gel responsiveness may be associated with lesional keratinocytes’ differentiation and local enteric recycling enzymatic capacities. Provided additional studies substantiate these findings, baseline protein levels could be used in a “personalized medicine approach”toidentify OIN lesions with a high probability of responsiveness. Notably, the highest pretreatment levels of differentiation-associated proteins were detected in the most responsive BRB gel cohort.

The observed post treatment lesional recurrences were not surprising, particularly because over 70% of the patients enrolled in this trial had histories of multiple recurrences of the OIN lesion selected for treatment. These recurrences, which are consistent with retention of genetically altered, long-lived stem cells at the lesional site, emphasize the need for effective, non-toxic, long-term chemoprevention strategies.

This study shares shortcomings with other OIN trials. First is the dynamic nature of OIN lesions. OIN lesions with a homogenous clinical appearance can still demonstrate molecular and/or histologic heterogeneity (41). Also, as a result of ongoing epithelial turnover baseline to post treatment biopsies are not direct comparisons. Instead, these measurements assess the effects of treatment on transient amplifying and more mature lesional keratinocytes over time. Furthermore, low patient numbers precluded our ability to determine whether or not clinical site or baseline histologic grade affected therapeutic responsiveness. Another common clinical trial challenge is the inter-patient variation in responsiveness. Our data imply these results reflect differences in local tissue absorption and the extensive variability in human oral mucosal metabolic bioactivation, local enteric recycling and keratinocyte differentiation-associated enzymes (19).

A recent editorial by a well-respected oral cancer chemoprevention researcher helps to place our results in perspective (42). The presence of LOH at specific chromosomal loci (3p and 9p) was acknowledged as the most consistent molecular marker of oral cancer risk (38, 41). Also discussed was the in ability to identify a standard systemic treatment protocol despite numerous, costly OIN chemoprevention clinical trials (42). In this context, BRB gel outcomes, which include significant reduction in OIN LOH events, lesional size and histologic grade without adverse effects, are favorable.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), which arises from its premalignant precursor oral intraepithelial neoplasia (OIN), is a world-wide health problem. While not all OIN lesions will transform, approximately 30% of the higher-grade lesions progress to OSCC. Furthermore, OIN lesions often recur despite complete surgical excision. Numerous chemoprevention studies have therefore attempted to induce regression in or prevent progression of OIN lesions. Modest success and dose-limiting toxicities were often the outcomes of these clinical trials. The majority of previous OIN clinical studies relied upon systemic chemopreventive agent administration. In contrast, this study assessed the effects of a food-based (freeze-dried black raspberries) bioadhesive gel on OIN lesions. Our results, which demonstrate BRB gel significantly reduces loss of heterozygosity, lesional size and histologic grade in OIN lesions without any toxicities combined the absence of such effects in the placebo gel cohort, are favorable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their appreciation for the expertise provided by Ohio State University College of Dentistry’s Oral Pathology histotechnologists, Mary Lloyd and Mary Marin. We also wish to acknowledge the excellent patient support provided by Wendy Lamm, CDA, Dental Research Clinic Coordinator, School of Dentistry, University of North Carolina.

Financial support: This study was supported by NIH NCI RC2 CA148099.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: No potential conflicts of interest were identified.

References

- 1.Scully C, Bagan J. Oral squamous cell carcinoma overview. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho MW, Field EA, Field JK, Risk JM, Rajlawat BP, Rogers SN, et al. Outcomes of oral squamous cell carcinoma arising from oral epithelial dysplasia: rationale for monitoring premalignant oral lesions in a multidisciplinary clinic. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:594–599. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers SN, Brown JS, Woolgar JA, Lowe D, Magennis P, Shaw RJ, et al. Survival following primary surgery for oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers SN, Scott J, Chakrabati A, Lowe D. The patients' account of outcome following primary surgery for oral and oropharyngeal cancer using a 'quality of life' questionnaire. Eur J Cancer Care. 2008;17:182–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverman S, Jr, Gorsky M, Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation. A follow-up study of 257 patients. Cancer. 1984;53:563–568. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3<563::aid-cncr2820530332>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lumerman H, Freedman P, Kerpel S. Oral epithelial dysplasia and the development of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnaoutakis D, Bishop J, Westra W, Califano JA. Recurrence patterns and management of oral cavity premalignant lesions. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:814–817. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Lee JJ, William WN, Jr, Martin JW, Thomas M, Kim ES, et al. Randomized trial of 13-cis retinoic acid compared with retinyl palmitate with or without beta-carotene in oral premalignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:599–604. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsao AS, Liu D, Martin J, Tang XM, Lee JJ, El-Naggar AK, et al. Phase II randomized, placebo-controlled trial of green tea extract in patients with high-risk oral premalignant lesions. Cancer Prev Res. 2009;2:931–941. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papadimitrakopoulou VA, William WN, Jr, Dannenberg AJ, Lippman SM, Lee JJ, Ondrey FG. Pilot randomized phase II study of celecoxib in oral premalignant lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2095–2101. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saba N, Hurwitz SJ, Kono S, Yang CS, Zhao Y, Chen Z, et al. Chemoprevention of Head and Neck Cancer with Celecoxib and Erlotinib: Results of a Phase 1b and Pharmacokinetic Study. Cancer Prev Res. 2013 doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0215. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mallery SR, Zwick JC, Pei P, Tong M, Larsen PE, Shumway BS, et al. Topical application of a bioadhesive black raspberry gel modulates gene expression and reduces cyclooxygenase 2 protein in human premalignant oral lesions. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4945–4957. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shumway BS, Kresty LA, Larsen PE, Zwick JC, Lu B, Fields HW, et al. Effects of a topically applied bioadhesive berry gel on loss of heterozygosity indices in premalignant oral lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2421–2430. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang LS, Stoner GD. Anthocyanins and their role in cancer prevention. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue H, Aziz RM, Sun N, Cassady JM, Kamendulis LM, Xu Y, et al. Inhibition of cellular transformation by berry extracts. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:351–356. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kresty LA, Morse MA, Morgan C, Carlton PS, Lu J, Gupta A, et al. Chemoprevention of esophageal tumorigenesis by dietary administration of lyophilized black raspberries. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6112–6119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallery SR, Budendorf DE, Larsen MP, Pei P, Tong M, Holpuch AS, et al. Effects of human oral mucosal tissue, saliva, and oral microflora on intraoral metabolism and bioactivation of black raspberry anthocyanins. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:1209–1221. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbey LM, Kaugars GE, Gunsolley JC, et al. Intraexaminer and interexaminer reliability in the diagnosis of oral epithelial dysplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80:188–191. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canzian F, Salovaara R, Hemminki A, et al. Semiautomated assessment of loss of heterozygosity and replication error in tumors. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3331–3337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoner GD, Wang LS, Zikri N, Chen T, Hecht SS, Huang C, et al. Cancer prevention with freeze-dried berries and berry components. Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17:403–410. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hecht SS, Huang C, Stoner GD, Li J, Kenney PMJ, Sturla SJ, et al. Identification of cyanidin glycosides as constituents of freeze-dried black raspberries which inhibit anti-benzo[a]pyrene-7,8-diol-9,10-epoxide induced NFκB and AP-1 activity. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1617–1626. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoner GD, Wang LS, Casto BC. Laboratory and clinical studies of cancer chemoprevention by antioxidants in berries. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1665–1674. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webb MR, Min K, Ebeler SE. Anthocyanin Interactions with DNA: Intercalation, Topoisomerase I Inhibition and Oxidative Reactions. J Food Biochem. 2008;32:576–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2008.00181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terahara N, Matsui T. Structure and Functionalities of Acylated Anthocyanins. In: Shibamoto T, et al., editors. ACS Symposium Series, Functional Food and Health. Washington DC: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang C, Zhang D, Li J, Tong Q, Stoner GD. Differential inhibition of UV-induced activation of NF kappa B and AP-1 by extracts from black raspberries, strawberries, and blueberries. Nutr Cancer. 2007;58:205–212. doi: 10.1080/01635580701328453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walle T, Browning AM, Steed LL, Reed SG, Walle UK. Flavonoid glucosides are hydrolyzed and thus activated in the oral cavity in humans. J Nutr. 2005;135:48–52. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodward GM, Needs PW, Kay CD. Anthocyanin-derived phenolic acids form glucuronides following simulated gastrointestinal digestion and microsomal glucuronidation. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:378–386. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201000355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swida A, Woyda-Ploszczyca A, Jarmuszkiewicz W. Redox state of quinone affects sensitivity of Acanthamoeba castellanii mitochondrial uncoupling protein to purine nucleotides. Biochem J. 2008;413:359–367. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodrigo KA, Rawal Y, Renner RJ, Schwartz SJ, Tian Q, Larsen PE, et al. Suppression of the tumorigenic phenotype in human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells by an ethanol extract derived from freeze-dried black raspberries. Nutr Cancer. 2006;54:58–68. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5401_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neville BW, Day TA. Oral cancer and precancerous lesions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:195–215. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.4.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Clayman GL, Shin DM, Myers JN, Gillenwater AM, Goepfert H, et al. Biochemoprevention for dysplastic lesions of the upper aerodigestive tract. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:1083–1089. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.10.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao S, Basu S, Yang G, Deb A, Hu M. Oral bioavailability challenges of natural products used in cancer chemoprevention. Pro in Chem. 2013;25:1553–1574. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ugalde CM, Liu Z, Ren C, Chan KK, Rodrigo KA, Ling Y, et al. Distribution of anthocyanins delivered from a bioadhesive black raspberry gel following topical intraoral application in normal healthy volunteers. Pharm Res. 2009;26:977–986. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9806-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graveland AP, Bremmer JF, de Maaker M, Brink A, Cobussen P, Zwart M, et al. Molecular screening of oral precancer. Oral Oncol. 2013;8 doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.09.005. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kresty LA, Mallery SR, Knobloch TJ, Li J, Lloyd M, Casto BC, et al. Frequent alterations of p16INK4a and p14ARF in oral proliferative verrucous leukoplakia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3179–3187. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Poh CF, Williams M, Laronde DM, Berean K, Gardner PJ, et al. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) profiles--validated risk predictors for progression to oral cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:1081–1089. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mao L, Lee JS, Fan YH, Ro JY, Batsakis JG, Lippman S, et al. Frequent microsatellite alterations at chromosomes 9p21 and 3p14 in oral premalignant lesions and their value in cancer risk assessment. Nat Med. 1996;2:682–685. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mao L, El-Naggar AK, Papadimitrakopoulou V, Shin DM, Shin HC, Fan Y, et al. Phenotype and genotype of advanced premalignant head and neck lesions after chemopreventive therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1545–1551. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.20.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bremmer JF, Graveland AP, Brink A, Braakhuis BJM, Dirk J, Kuik DJ, et al. Screening for Oral Precancer with Noninvasive Genetic Cytology. Cancer Prev Res. 2009;2:128–133. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.William WN., Jr Oral premalignant lesions: any progress with systemic therapies? Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:205–210. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835091bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.