Abstract

Purpose

To analyze a multidisciplinary community experience with oncoplastic breast surgery (OBS) and postoperative radiation therapy (RT).

Methods

The records of 79 patients with localized breast cancer who underwent OBS + RT were reviewed. OBS included immediate reconstruction and contralateral mammoreduction. All patients had negative surgical margins. Whole breast RT was delivered without boost. A subset of 44 patients agreed to complete a validated quality of life survey pre-RT, post-RT, 6 months after RT, and at final follow-up assessing cosmesis and treatment satisfaction.

Results

Sixty seven patients (85%) were Caucasian. Median age was 62. Median interval between OBS and RT start was 9.6 weeks. Median RT dose was 46 Gy. Fourteen patients (18%) developed surgical toxicities prior to RT. Five patients (6%) developed RT toxicities. Physician rating of cosmesis post-RT was: 3% excellent, 94% good, and 4% fair. Cosmesis was rated as excellent or good by 87% of patients pre-RT, 82% post-RT, 75% at 6 months, and 88% at the final follow-up. Treatment satisfaction was rated as “total” or “somewhat” by 97% of patients pre-RT, 93% post-RT, 75% at 6 months, and 96% at final follow-up. No significant relation was found between patient or treatment-related factors and toxicity. Local control is 100% at median follow-up of 2.9 years.

Conclusions

OBS followed by RT resulted in acceptable toxicity and favorable physician-rated cosmesis in this large community series. Patients’ ratings of cosmesis and treatment satisfaction were initially high, decreasing at 6 months, returning near baseline at final follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, oncoplastic breast surgery (OBS) has extended the boundaries of breast conservation for patients with breast cancer. Combining breast conserving resection and plastic surgical reconstruction, OBS may allow patients with central and/or large breast tumors to achieve optimal oncologic and aesthetic outcomes (1–4). The existing medical literature on this topic consists predominantly of surgical reports from university hospitals. Moreover, outcomes data are sparse in regard to combination treatment with OBS followed by postoperative radiation therapy (RT) (5,6).

Cosmesis is a critical endpoint for breast conservation. There is strong evidence that after standard lumpectomy followed by postoperative RT, cosmesis suffers with increasing breast tissue resection volumes (7–9). Since OBS techniques generally result in larger resection volumes and increased surgical manipulation of breast tissue than lumpectomy, there is significant potential for worse aesthetic outcomes when OBS is followed by standard postoperative RT to the whole breast (10–12). In that regard, herein we present early outcomes, including patient reported cosmesis and satisfaction with OBS and RT at a large community hospital.

METHODS

Patients with localized breast cancer who underwent OBS followed by standard RT at Coastal Carolina Radiation Oncology (CCRO) between July, 2006 and February, 2012 were reviewed. The protocol for gathering and reporting this data was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of New Hanover Regional Medical Center. In 2011, the authors initiated a prospective phase II clinical trial of hypofractionated RT after OBS and these patients are excluded from the current analysis.

Surgery was performed as a single procedure in all cases. All patients had intraoperative evaluation of surgical margins by frozen section and, if initially positive, underwent immediate re-excision, all with ultimately negative surgical margins. Patients underwent partial mastectomy with immediate ipsilateral reconstruction and contralateral mammoreduction. Reconstruction was achieved utilizing the Modified Wise pattern inferior pedicle mastopexy in most cases. For patients with tumors in the 5:00 to 7:00 axis, a superior pedicle, superomedial pedicle, or free nipple graft were performed. Surgical management of the axilla was dependent upon disease extent. During this time frame, patients found to have a positive sentinel node routinely underwent completion axillary nodal dissection.

The time interval between surgery and the initiation of RT was recorded. Postoperative RT was delivered utilizing standard fractionation of 1.8–2.0 Gy daily to the whole breast with no boost, since no tumor bed was discernible to target. The treating radiation oncologist’s evaluation of cosmesis was recorded at one to three months post-RT as: excellent, good, fair, or poor for each patient. No attempt was made to control for differences in perception of cosmesis among the treating physicians.

Beginning in November 2009, patients who had undergone OBS and were seen in consultation at CCRO for consideration of postoperative RT were offered participation in a prospective quality of life analysis. These 44 patients agreed to complete the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) Quality of Life Baseline (QLB) questionnaire pre-RT, post-RT, and 6-months after RT assessing their cosmesis and satisfaction with treatment. Final follow-up to assess patient reported cosmesis and treatment satisfaction was via personal phone call from the lead author. The QLB questionnaire was the same instrument utilized for the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B39 trial. It included specific questions regarding breast size, shape, appearance and pain, as well as arm pain and stiffness. However, for the purposes of the current analysis, patient reported outcomes were limited to overall cosmesis and treatment satisfaction. Possible choices for patients’ assessment of cosmesis were the same as those for physicians: excellent, good, fair, or poor. Patients were also provided choices within the QLB survey to describe their overall treatment satisfaction pre-RT, post-RT, at 6 months, and at the final follow-up as: totally satisfied, somewhat satisfied, neutral, somewhat dissatisfied, or unsatisfied. The first two choices for this survey question were considered favorable.

Descriptive statistics were reported as frequencies, medians and ranges. A logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the potential impact of patient, tumor, and treatment factors on the development of toxicity and ordinal logistic regressions assessed the relationships between survey ratings and demographic/treatment variables. Comparisons of ratings between pre-RT, post-RT, 6MO, and final surveys were tested by using an ANCOVA on the ranks, adjusting for the individual patient. Tests were run using SAS 9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). All tests were two tailed and a level of significance, α = 0.05 was used.

RESULTS

During 2008–2011, 79 patients were included in the study. Patients were predominantly Caucasian (85%, Table 1), with a median age of 61.9 years. The vast majority (91%) had American Joint Commission on Cancer stage 0 – II disease.

Table 1.

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

| All Subjects N = 79 |

Surveyed Subjects N = 30 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 61.9 (34.9–76.9) | 65.2 (35.7 – 73.6) |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 66 (84.6) | 25 (83.3) |

| African American | 12 (15.4) | 5 (16.7) |

| T Stage | ||

| Tis | 7 (9.3) | 3 (10.7) |

| T1 | 56 (74.7) | 17 (60.7) |

| T2 | 12 (16.0) | 8 (28.6) |

| N Stage | ||

| N0 | 44 (73.3) | 13 (65.0) |

| N1 | 10 (16.7) | 4 (20.0) |

| N2 | 2 (3.3) | 2 (10.0) |

| N3 | 4 (6.7) | 1 (5.0) |

| AJCC Stage | ||

| 0 | 7 (9.2) | 3 (10.3) |

| I | 46 (60.5) | 14 (48.3) |

| IIA | 13 (17.1) | 6 (20.7) |

| IIB | 3 (4.0) | 2 (6.9) |

| III | 7 (9.2) | 4 (13.8) |

Data reported in Median (Min-Max) or N(%).

Axillary surgery consisted of sentinel lymph node biopsy only in the majority of patients (Table 2). Thirty patients (38%) received chemotherapy sequentially with RT, 8 (27%) of whom received it neoadjuvantly. The median time interval between OBS and initiation of RT was 9.6 weeks, though this interval ranged from 3 to 35 weeks since 22 patients received chemotherapy adjuvantly, between surgery and RT. The median RT dose was 46 Gy.

Table 2.

Treatment Characteristics

| All Subjects N = 79 |

Surveyed Subjects N = 30 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Nodal Surgery | |||

| Sentinel Node Biopsy Only | 55 (70) | ||

| Axillary Dissection | 22 (28) | ||

|

|

|||

| Time Interval, Surgery to Radiation Therapy (wk) | 9.6 (3.1 – 35.0) | 9.9 (4.9 – 26.0) | |

| Time Interval, Surgery to Follow Up (wk) | 152.9 (12.7 – 300.4) | 126.4 (12.7 – 188.4) | |

| Radiation Therapy Dose (Gy) | 46.0 (40.0 – 50.4) | 46.9 (42.7 – 50.4) | |

| Chemotherapy | 30 (39.0) | 12 (41.4) | |

|

|

|||

| Neoadjuvant | 8 (26.7) | ||

| Adjuvant | 22 (73.3) | ||

|

|

|||

Data reported in Median (Min-Max) or N(%).

Fourteen patients (18%) developed surgical toxicities prior to the initiation of RT (Table 3). Among 22 patients who underwent standard axillary lymph node dissection, 4 (18%) developed symptomatic arm lymphedema. Other common surgical toxicities were mastitis and delayed wound healing. Five patients (6%) developed acute RT toxicities, all of which were skin-related. The treating radiation oncologist rated patient cosmesis at 1–3 months post-RT as 3% excellent, 94% good, and 4% fair. No significant relationship was found between toxicity and the treatment related variables of chemotherapy or radiation dose (Table 4). At a median follow-up of 2.9 years, no patient had developed local or regional recurrence.

Table 3.

Toxicities

| Acute | Chronic | |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical Toxicities | 14 (18.0) | 5 (16.7) |

| Mastitis | 4 (28.5)* | 0 (0) |

| Delayed Wound Healing | 4 (28.5) | 2 (40.0) |

| Symptomatic Arm Lymphedema | 4 (28.5) | 2 (40.0) |

| Lymphangitis | 1 (7.1) | 1 (20.0) |

| Symptomatic Breast Edema | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) |

| RT Toxicities | 5 (6.4) | 2 (6.7) |

| RTOG Grade 2 desquamation | 2 (40.0) | 2 (100) |

| RTOG Grade 3 desquamation | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) |

| Mastitis | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) |

| Wound Abscess | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0) |

Table 4.

Effect of Treatment Options on Toxicity

| Treatment | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Chemotherapy | 1.052 (0.164–6.737) |

| Radiation Dose | 1.139 (0.773–1.677) |

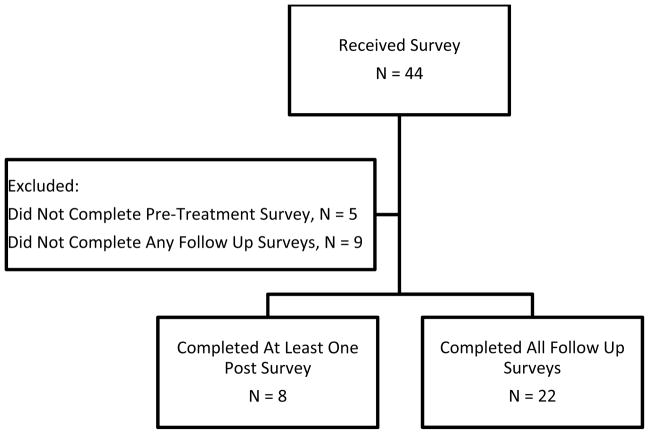

Beginning in November 2009, forty-four patients received the RTOG QLB questionnaires for prospective evaluation of their cosmesis and treatment satisfaction. Among this group, 14 patients were excluded from the analysis for either not having completed a pre-treatment questionnaire or not having completed any of the three possible follow-up surveys (post-treatment, six month, or final). A total of 22 subjects completed all baseline and follow-up questionnaires for a complete response rate of 50%. However, those patients who had completed the pre-treatment survey and at least one follow-up survey were included, for an overall response rate of 68% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution and completion of RTOG QLB Questionnaire

Cosmesis was rated as excellent or good by 87% of patients pre-RT, 82% post-RT, 75% at 6 months, and 88% at the final follow-up. Patient ratings at pre-RT, post-RT, 6 months, and at final follow-up were not significantly different from each other; nor did ratings significantly increase or decrease over time (p = 0.7795, Table 5). An ordinal logistic regression of the cosmesis rating showed that age, whether chemotherapy was received, RT dose, time to RT, or follow-up time had no significant effect on pre-RT, post-RT, 6 month, or final follow-up scores.

Table 5.

Cosmesis and Treatment Scores Over Time

| Patient Assessment | Score | Pre N = 30 |

Post N = 28 |

6 Months N = 24 |

Final* N = 24 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmesis | Excellent | 8 (26.7) | 7 (25.0) | 5 (20.8) | 8 (33.3) | 0.7795 |

| Good | 18 (60.0) | 16 (57.1) | 13 (54.2) | 13 (54.2) | ||

| Fair | 4 (13.3) | 3 (10.7) | 6 (25.0) | 1 (4.2) | ||

| Poor | 0 (0) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Overall Satisfaction | Totally Satisfied | 19 (63.3) | 22 (78.6) | 16 (66.7) | 15 (62.5) | 0.1638 |

| Somewhat Satisfied | 10 (33.3) | 4 (14.3) | 2 (8.3) | 8 (33.3) | ||

| Neutral | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.6) | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Somewhat Dissatisfied | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 4 (16.7) | 1 (4.2) | ||

| Totally Dissatisfied | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Data reported in N (%)

Final F/U between 1 and 3 years post-surgery

Treatment satisfaction was rated as “total” or “somewhat” by 97% of patients pre-RT, 93% post-RT, 75% at 6 months, and 96% at final follow-up (p = 0.1638). As with cosmesis, ratings at each follow-up interval did not significantly differ from each other. There was a similar trend revealing lower treatment satisfaction at 6 months which improved at final follow-up. The ordinal regression analysis showed no relationship between demographic or treatment variables and treatment satisfaction. Though we tried to include race as a factor, the inclusion of this variable in the regression analysis resulted in quasi-separation of data due to small numbers (12 African American patients), which required this variable to be removed from the model.

DISCUSSION

This report describes reasonable early results with breast conservation utilizing oncoplastic breast surgery (OBS) followed by postoperative radiation therapy (RT) to the whole breast. Reports from major university hospitals reveal favorable evaluations of cosmesis by the treating surgeons (13–16). The current report reveals similar favorable, albeit early, evaluations by radiation oncologists. However, since evaluations were made by the treating physician, bias is a factor. More importantly, patients’ prospective evaluation of early cosmesis and overall satisfaction with OBS followed by RT was relatively high. These results are comparable to patients’ assessments of their aesthetic outcomes in reported surgical series (17,18). There was a decrement in cosmesis as evaluated by patients at six months after completing surgery and RT. This difference was not statistically significant, an unsurprising result given the relatively small size of the group in this report. Unfortunately, a control group of patients treated with OBS alone (no adjuvant RT) is lacking. Thus, it remains unknown whether the trend of decline in QOL scores at six months after completion of postoperative RT may be clinically significant. Potential reasons for this decline in patients’ perceived cosmesis at 6 months after treatment include RT fibrosis, progressive surgical scarring, or merely patients’ evolving opinions of their cosmesis over time. The upward trend in patient reported cosmesis and treatment satisfaction between the 6 month mark and final follow-up is encouraging. However, since the final follow-up for these two patient reported outcomes was via phone call from the lead author, patients may have reported answers which they thought would be more pleasing to the physician.

In regard to long-term oncologic outcomes, the relatively short follow-up in the current report limits meaningful commentary for this group of patients with early stage breast cancer. The surgical literature supports an ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence rate ranging from 0–2% annually for patients with early stage disease treated with OBS (19–21). Details are lacking about delivery of postoperative RT in most OBS reports, making the current report quite valuable. Because post-lumpectomy RT has been proven to improve not only local control but also survival, it remains a standard component of breast conservation therapy (22). The potential to achieve more “widely negative” surgical margins with OBS may tempt some surgeons to forego patient referral to radiation oncology. Unfortunately, there is no data to substantiate the seemingly intuitive assumption that wider margins result in improved local tumor control or survival. Which subset of patients treated with oncoplastic techniques for their breast conserving surgery (if any) does not require postoperative RT in order to minimize cancer recurrence risk? This question remains to be answered, ideally via a clinical trial.

Shorter RT fractionation schemes have proven to be safe and effective in randomized trials for patients with early stage breast cancer treated with standard lumpectomy (23,24). However, theoretical concerns arise with respect to fibrosis when higher daily doses of RT are delivered after large volume breast resections, and in patients undergoing OBS, the surgery is more extensive than that of a standard lumpectomy. Our group has initiated a phase II clinical trial evaluating cosmesis with hypofractionated RT after OBS to evaluate this question. Accrual has been brisk and trial closure is anticipated in late 2013.

There are other limitations to the current study. The retrospective nature of the analysis on the entire patient cohort (N=79) may have resulted in selection bias. The authors have attempted to account for this potential bias by including all patients who underwent OBS, were referred for radiation oncology consultation, and underwent postoperative RT at CCRO. The quality of any retrospective case series is also dependent upon the accuracy and completeness of the medical record. No attempt was made to account for differences in perceived cosmesis among the treating radiation oncologists. The prospective subgroup assessment of cosmesis and overall treatment satisfaction is limited by small numbers and moderate questionnaire response rate. Multivariate analysis of the potential impact of patient and treatment factors on toxicity revealed no clear correlation, though this type of analysis is also hampered by small sample size. With a larger prospective patient cohort, as in our ongoing clinical trial, comparisons over time (between baseline and post-treatment) may be more meaningful.

CONCLUSIONS

Oncoplastic breast surgery followed by standard whole breast RT yielded an acceptable toxicity profile and favorable physician-rated cosmesis in this large community series. Patients’ ratings of cosmesis and treatment satisfaction were relatively high overall, with an apparent nadir at 6 months after surgery and adjuvant RT. Late cosmesis, as well as long-term oncologic outcomes, will be evaluated for a similar group of patients treated on our prospective phase II trial of oncoplastic breast surgery followed by hypofractionated RT.

Acknowledgments

Support:

Dr. Maguire receives Cancer Disparities Research Partnership (CDRP) grant funding from National Cancer Institute: NIH #U54CA-14215201

Contributor Information

Patrick D. Maguire, Coastal Carolina Radiation Oncology.

Michael A. Nichols, Coastal Carolina Radiation Oncology.

Ashley Adams, South East Area Health Education Center.

References

- 1.Anderson BO, Masetti R, Silverstein MJ. Oncoplastic approaches to partial mastectomy: an overview of volume-displacement techniques. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:145–57. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)01765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masetti R, DiLeone A, Franceschini G, et al. Oncoplastic techniques in the conservative surgical treatment of breast cancer: an overview. Breast J. 2006;12:S174–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry MG, Fitoussi AD, Curnier A, et al. Oncoplastic breast surgery: a review and systematic approach. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:1233–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bong J, Parker PA, Clapper R, Dooley W. Clinical Series of Oncoplastic Mastopexy to Optimize Cosmesis of Large-Volume Resections for Breast Conservation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3247–51. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1140-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith ML, Evans GR, Gurlek A, et al. Reduction mammaplasty: its role in breast conservation surgery for early-stage breast cancer. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;41:234–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clough KB, Lewis JS, Couturaud B, et al. Oncoplastic techniques allow extensive resections for breast-conserving therapy of breast carcinomas. Ann Surg. 2003;237:26–34. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivotto IA, Rose MA, Osteen RT, et al. Late cosmetic outcomes after conservative surgery and radiotherapy: analysis of causes of cosmetic failure. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17:747–53. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wazer DE, DiPetrillo T, Schmidt-Ullrich R, et al. Factors influencing cosmetic outcome and complication risk after conservative surgery and radiotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:356–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curran D, van Dongen JP, Aaronseon NK, et al. Quality of life of early-stage breast cancer patients treated with radical mastectomy or breast-conserving procedures: results of EORTC Trial 10801. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), Breast Cancer Co-operative Group (BCCG) Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:307–14. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaur N, Petit JY, Rietjens M, et al. Comparative study of surgical margins in oncoplastic surgery and quadrantectomy in breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:539–45. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giacolone PL, Roger P, Dubon O, et al. Comparative study of the accuracy of breast resection in oncoplastic surgery and quadrantectomy in breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:605–14. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan SW, Cheung PS, Lam SH. Cosmetic outcome and percentage of breast volume excision in oncoplastic breast conserving surgery. World J Surg. 2010;34:1447–52. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asgeirsson KS, Rasheed T, McCulley SJ, Macmillan RD. Oncological and cosmetic outcomes of oncoplastic breast conserving surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:817–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzal F, Mittlboeck M, Trishler H, et al. Breast-conserving therapy for centrally located breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2008;247:470–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815b6991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veiga DF, Veiga-Filho J, Ribiero LM, et al. Evaluations of aesthetic outcomes of oncoplastic surgery by surgeons of different gender and specialty: a prospective controlled study. Breast. 2011;20:407–12. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fittoussi AD, Berry MG, Fama F, et al. Oncoplastic breast surgery for cancer: analysis of 540 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:454–62. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c82d3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goffman TE, Schneider H, Hay K, et al. Cosmesis with bilateral mammoreduction for conservative breast cancer treatment. Breast J. 2005;11:195–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel KM, Hannan CM, Gatti ME, Nahabedian MY. A head-to-head comparison of quality of life and aesthetic outcomes following immediate, staged-immediate, and delayed oncoplastic reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2167–75. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182131c1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rietjens M, Urban CA, Rey PC, et al. Long-term oncological results of breast conservative treatment with oncoplastic surgery. Breast. 2007;16:387–95. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meretolja TJ, Svarvar C, Jahkola TA. Outcome of oncoplastic breast surgery in 90 prospective patients. Am J Surg. 2010;200:224–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roughton MC, Shenaq D, Jaskowiak N, et al. Optimizing Delivery of Breast Conservation Therapy: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Oncoplastic Surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2011 doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31822afa99. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery on 10-year recurrence and 15-year breast cancer death: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 10,801 women in 17 randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378:1707–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61629-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whelan TJ, Pignol JP, Levine MN, et al. Long-Term results of Hypofractionated Radiation Therapy for Breast Cancer. N Eng J Med. 2010;362:513–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.START Trialists’ Group. The UK Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy (START) Trial B of radiotherapy hypofractionation for treatment of early breast cancer: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1098–1107. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60348-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]