Abstract

Background

Hard metal lung disease has various pathological patterns including giant cell interstitial pneumonia (GIP) and usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP). Although the UIP pattern is considered the prominent feature in advanced disease, it is unknown whether GIP finally progresses to the UIP pattern.

Objectives

To clarify clinical, pathological and elemental differences between the GIP and UIP patterns in hard metal lung disease.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of patients from 17 institutes participating in the 10th annual meeting of the Tokyo Research Group for Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Diseases, 2009. Nineteen patients (seven female) diagnosed with hard metal lung disease by the presence of tungsten in lung specimens were studied.

Results

Fourteen cases were pathologically diagnosed as GIP or centrilobular inflammation/fibrosing. The other five cases were the UIP pattern or upper lobe fibrosis. Elemental analyses of lung specimens of GIP showed tungsten throughout the centrilobular fibrotic areas. In the UIP pattern, tungsten was detected in the periarteriolar area with subpleural fibrosis, but no association with centrilobular fibrosis or inflammatory cell infiltration. The GIP group was younger (43.1 vs 58.6 years), with shorter exposure duration (73 vs 285 months; p<0.01), lower serum KL-6 (398 vs 710 U/mL) and higher lymphocyte percentage in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (31.5% vs 3.22%; p<0.05) than the fibrosis group.

Conclusions

The UIP pattern or upper lobe fibrosis is remarkably different from GIP in distribution of hard metal elements, associated interstitial inflammation and fibrosis, and clinical features. In hard metal lung disease, the UIP pattern or upper lobe fibrosis may not be an advanced form of GIP.

Keywords: OCCUPATIONAL & INDUSTRIAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Nineteen cases of hard metal lung disease, a rare occupational lung disease, were collected and their clinical features documented.

Lung tissue from all the patients was elementally analysed by a patented technique, an improved element analysis using electron probe microanalysers with wavelength dispersive spectrometer.

Since the incidences of hard metal lung disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in potentially exposed populations and in the general population are unknown, the probability that someone with hard metal exposure will develop ‘idiopathic’ usual interstitial pneumonia/IPF is also unknown.

Introduction

Hard metal is a synthetic compound that combines tungsten carbide with cobalt. Patients exposed to hard metal may develop occupational asthma, a syndrome resembling hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), or interstitial lung disease which is recognised as hard metal lung disease.1–3 In many cases of hard metal lung disease, multinucleated giant cells with centrilobular fibrosis are prominent, resulting in a pattern of giant cell interstitial pneumonia (GIP).4–6 We have shown that hard metal accumulated in the centrilobular area may trigger the inflammation in cooperation with CD163 monocyte-macrophages and CD8 lymphocytes using electron probe microanalysers with a wavelength dispersive spectrometer (EPMA-WDS).7 In addition to classical GIP, hard metal lung disease has a variety of pathological patterns, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, obliterative bronchiolitis and the usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern.4 8 The lesions of classical GIP are usually centred on the centrilobular areas. However, the key histological features of UIP are predominantly distributed at the periphery of the acinus or lobule.9 10 Hard metal lung disease has pathological patterns of both GIP and UIP, and the UIP pattern is thought to be the prominent feature in advanced cases of the disease.8 The key question is whether or not the UIP pattern is an advanced form of GIP. In order to elucidate relationship between GIP and lung fibrosis with detection of hard metal elements, we reviewed the clinical records of cases with tungsten in lung tissue. We then elementally reexamined lung specimens by EPMA-WDS. We finally classified the patients into two groups according to the histological findings and statistically compared their clinical features. Pathological and elemental analyses in the study suggest that the UIP pattern or upper lobe fibrosis may be different from an end-stage form of GIP.

Methods

Patient population

We collected patients by requesting details of cases of hard metal lung disease from the major medical institutes and hospitals all over Japan for the 10th annual meeting of the Tokyo Research Group for Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Diseases, 2009. We obtained information such as age, gender, duration of hard metal exposure, history of pneumothorax, history of allergy, symptoms, physical findings, serum levels of Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) and SP-D, arterial blood gas data, pulmonary function tests, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell profiles, and treatment and prognosis in order to make a database of patient profiles. We acquired consent from all treating physicians for each identified case according to the Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies from The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Committee of Ethics, Niigata University, approved the EPMA-WDS study protocol (#396).

High-resolution CT scan findings

All patients with hard metal lung disease except one had undergone high-resolution CT (HRCT) scanning. Two radiologists (observers) who were blinded to the clinical, laboratory or pulmonary function test results evaluated the CT scan findings. The observers judged each CT scan for the presence or absence of three main features: centrilobular nodules, ground glass opacity, and pneumothorax. They also noted other remarkable findings—traction bronchiectasis, reticular pattern, subpleural linear opacity, consolidation, bulla, centrilobular emphysema, atelectasis and bronchial wall thickening—and entered these results into a data sheet independently. After evaluation, disagreement on the results between the observers for some HRCT scans was resolved by discussion and consensus.

Sample preparation and pathological study

Each tissue sample was serially cut into 3 μm-thickness sections and subjected to pathological study and EPMA-WDS analysis. For pathological study, formalin-fixed 3 μm serial sections were stained with H&E and the Elastica van Gieson method. Two pathologists (observers), who were blinded to clinical, laboratory or pulmonary function test results, evaluated the pathological findings. After evaluation, disagreement on the pathological diagnoses between the observers for some specimens was resolved by discussion and consensus.

Electron probe microanalysis

Examination of tissue sections with EPMA-WDS was performed according to procedures previously described.11 X-ray data were obtained with an EPMA-WDS (EPMA 8705, EPMA-1610, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). In order to have representative element maps, we first microscopically scanned tissue specimens and looked for lesions of centrilobular fibrosis with low magnification because hard metal related elements, tungsten/cobalt, were always found around centrilobular areas according to our experience. For EPMA analysis, we first screened areas of about 1.5 mm×1.5 mm maximum covering centrilobular lesions or fibrosing lesion of interstitial lung diseases observed by pathological study to make rough element maps. Then we focused on areas from 5×5 μm to 10×10 μm minimum to draw fine maps for elements. Each pixel in the focused areas in the tissue was scanned by three wavelength dispersive crystals: RAP, PET and LiF for screening elements of Al, K, RAP; Si, K, PET; Ti, K, LiF; Cr, K, LiF; Fe, K, LiF; Co, K, LiF; Ta, M, PET; W, M, PET; and Zn, L, RAP. Since generated X-ray signals from each pixel were the smallest part of a distribution map, we simultaneously obtained element maps with qualitative analyses of pixels in the focused area. The distribution of amino nitrogen corresponding to the pathological image was also mapped for each sample.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of categorical data were made with the χ2 or Fisher's exact test. Non-parametric numeric data were compared by the Mann–Whitney U test. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of subjects

When we held the Tokyo ILD Meeting, 22 cases were collected and suspected to be hard metal lung diseases due to occupational history and pathological findings, but three cases were excluded because tungsten or cobalt were not detected in the lung tissue. Nineteen patients were finally diagnosed as having hard metal lung disease because of the presence of tungsten in lung specimens detected by EPMA-WDS. In 4 of 19 patients, the presence of tungsten, cobalt or tantalum was not initially known but was subsequently proven by element analysis at the meeting.

Occupational history and clinical features are summarised in tables 1 and 2. Demographic findings in six of these patients have been reported previously (cases 2, 5, 7, 8, 10 and 16 corresponding to cases 1, 3, 5, 6, 14 and 16 in the 2007 report, respectively).7 All subjects had an occupational history of hard metal industry for 1–36 years. One patient (case 15) was doing deskwork in an insufficiently ventilated room of a hard metal grinding company. Five patients had an occupational history of hard metal industry but were not exposed at the diagnosis of hard metal lung disease. The delay between cessation of exposure and biopsy in the patients were 5 years, and 4, 2 and 6 months for cases 1, 2, 8 and 14, respectively. Case 10 had worked as a metal grinder for 6 years and then as a chimney cleaner at a copper mine for 32 years. He visited a hospital complaining of dry cough after 32 years’ work as a chimney cleaner and was finally diagnosed as having hard metal lung disease 4 years later by surgical biopsy. Five patients (cases 2, 5, 7, 8 and 15) had an allergic history and were patch tested for Co, Ni, Cr, Hg, Au, Zn, Mn, Ag, Pd, Pt, Sn, Cu, Fe, Al, In, Ir and Ti. Four of five patients who had undergone patch testing (cases 2, 5, 7 and 15) were found to be positive for cobalt. Pulmonary function tests revealed restrictive lung defect characterised by reduced vital capacity and lung diffusing capacity. BAL findings showed increased total cell counts, increased lymphocytes and eosinophils, with normal CD4/CD8 ratio. Bizarre multinucleated giant cells were noted in three patients.

Table 1.

Demographic features of subjects

| Case | Smoking | Occupational history (hard metal exposure) |

Exposure (year/months) start/duration |

Biopsy year | Exposure at diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | history | |||||

| 1 | 39 | M | Non | Hard metal shaping/drilling | 2000/12 | 2006 | No |

| 2 | 53 | M | Ex | Hard metal shaping/drilling | 2002/30 | 2002 | No |

| 3 | 21 | M | Non | Metal grinding | 2005/32 | 2008 | Yes |

| 4 | 42 | M | Ex | Hard metal shaping/drilling | 2005/36 | 2009 | Yes |

| 5 | 48 | M | Non | Metal grinding | 2000/48 | 2004 | NA |

| 6 | 45 | M | Non | Hard metal shaping/drilling | 1982/60 | 1987 | Yes |

| 7 | 32 | F | Non | Metal grinding | 1988/60 | 1993 | Yes |

| 8 | 32 | F | Non | Metal grinding | 1997/72 | 2003 | No |

| 9 | 44 | F | Non | Hard metal shaping/drilling | 1990/72 | 1996 | Yes |

| 10 | 62 | M | Non | Metal grinding | 1963/72 | 2003 | No |

| 11 | 40 | F | Non | Hard metal shaping/drilling | 1997/96 | 2005 | NA |

| 12 | 48 | M | Non | Metal grinding | 1981/120 | 1992 | NA |

| 13 | 49 | F | Non | Hard metal shaping/drilling | 1999/120 | 2009 | Yes |

| 14 | 65 | F | Non | Metal grinding | 1988/144 | 2000 | No |

| 15 | 50 | F | Non | Desk worker in hard metal factory | 1985/168 | 1996 | Yes |

| 16 | 53 | M | Non | Quality control of hard metals | 1974/264 | 2001 | NA |

| 17 | 60 | M | Ex | Hard metal shaping/drilling | 1972/276 | 1995 | Yes |

| 18 | 53 | M | Non | Hard metal shaping/drilling | 1971/372 | 2005 | Yes |

| 19 | 65 | M | Non | Hard metal shaping/drilling | 1963/444 | 2008 | Yes |

NA, not available.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients with hard metal lung disease

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Mean age at diagnosis (years) | 46.4±14.1 (21–65) |

| Gender | |

| M/F | 12/7 |

| Smoking history | |

| Cur/ex/never | 0/3/16 |

| Chief complaints | |

| Dry cough | 13/19 |

| Breath shortness | 8/19 |

| Pneumothorax | |

| Yes | 8/19 |

| Allergic history | |

| Yes | 5/19 |

| Patch test to cobalt | |

| Positive | 4/5 |

| Mean exposure duration (years) | 10.7±10.3 (1–36) |

| Physical findings | |

| Rales on auscultation | 11/19 |

| Fine crackles | 8/19 |

| Finger clubbing | 4/18 |

| Oedema of leg | 1/16 |

| Laboratory tests | |

| KL-6 | 502.7±267.5 U/mL |

| SP-D | 216.1±192.4 ng/mL |

| Pulmonary function tests | |

| VC, % predicted | 64.8±25.3% |

| FEV1 | 1.71±0.70 L |

| FEV1/FVC | 85.6±10.7% |

| DLco, % predicted | 53.4±17.0% |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage | |

| Total cell count | 3.13±2.11×105/mL |

| Lymphocytes | 24.3±22.3% |

| Neutrophils | 3.07±2.86% |

| Eosinophils | 3.01±5.03% |

| CD4/8 ratio | 1.65±2.96 |

Results expressed as mean±SD (range).

DLco, carbon monoxide diffusing capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; KL-6, Krebs von den Lungen 6; SP-D, surfactant protein D; VC, vital capacity.

Radiological findings

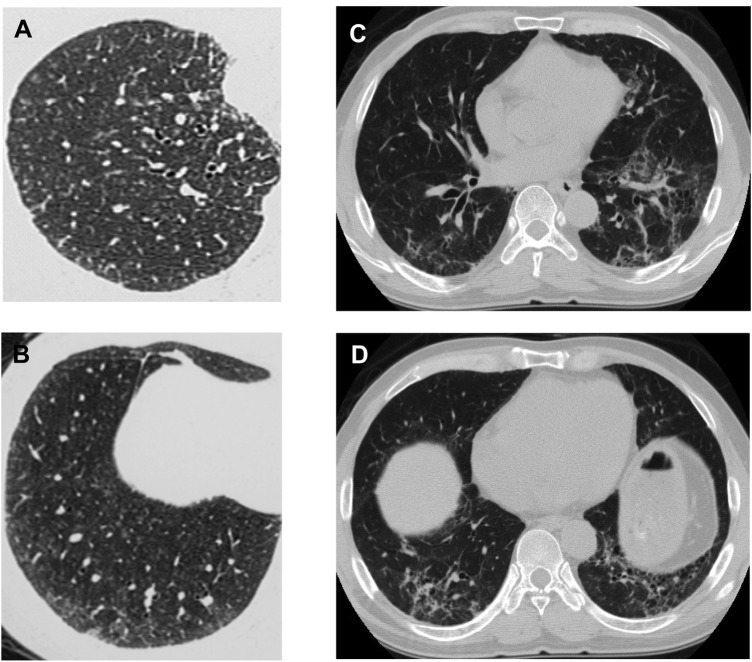

HRCT of all patients except one with hard metal lung disease were available for review of radiological findings. Conventional CT findings of case 12 were added to the table (table 3). Centrilobular nodules (figure 1A,B) and ground glass opacity were identified on chest CT of 16 patients. In some patients, reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis and subpleural curvilinear opacities were also present (figure 1C,D). Although centrilobular micronodular opacities were noted in those patients, they were not predominant.

Table 3.

Radiologic findings of patients with hard metal lung disease

| CT features |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | CL Nodules | GGO | PTx | Other findings | Radiological diagnosis |

| 1 | + | − | − | Bronchial wall thickening | Bronchitis (DPB like) |

| 2 | + | + | − | Reticular opacities | Chronic IP, NOS (NSIP or UIP) |

| 3 | + | + | + | Subacute HP | |

| 4 | + | − | + | Subpleural curvilinear opacities | Subacute HP |

| 5 | + | + | − | Subacute HP | |

| 6 | − | + | − | Reticular opacities, consolidation | Interstitial pneumonia NOS |

| 7 | + | + | + | Subacute HP | |

| 8 | + | + | − | Traction bronchiectasis | Subacute HP |

| 9 | + | + | − | Subacute HP | |

| 10 | + | + | − | Reticular opacities, traction bronchiectasis | UIP |

| 11 | + | − | + | Subacute HP | |

| 12 | + | + | + | Subpleural curvilinear opacities | Chronic HP |

| 13 | + | + | − | Subacute HP | |

| 14 | + | + | − | Traction bronchiectasis, apical cap | Chronic HP |

| 15 | + | + | + | Traction bronchiectasis | Subacute HP |

| 16 | − | + | + | Subpleural/peribronchovascular consolidation, atelectasis, bulla | Upper lobe predominant IP or chronic IP NOS |

| 17 | + | + | − | Bulla, centrilobular emphysema | UIP |

| 18 | − | + | − | Reticular opacities | Chronic IP, NOS (NSIP or UIP) |

| 19 | + | + | − | Reticular opacities | Chronic HP |

CL, centrilobular; DPB, diffuse panbronchiolitis; GGO, ground-glass opacities; HP, hypersensitivity pneumonitis; IP, interstitial pneumonia; NOS, not otherwise specified; NSIP, non-specific interstitial pneumonia; PTx, pneumothorax; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Figure 1.

High-resolution CT of the chest illustrating differences in the radiographic appearance of the lungs in the giant cell interstitial pneumonia (GIP) and the usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern. (A,B) In GIP of case 9, centrilobular micronodular opacities pathologically correspond to centrilobular fibrosis and giant cell accumulation within the alveolar space. (C,D) In the UIP pattern of case 10, reticular opacities and traction bronchiectasis are present with centrilobular micronodular opacities.

Pathological findings and elemental analysis

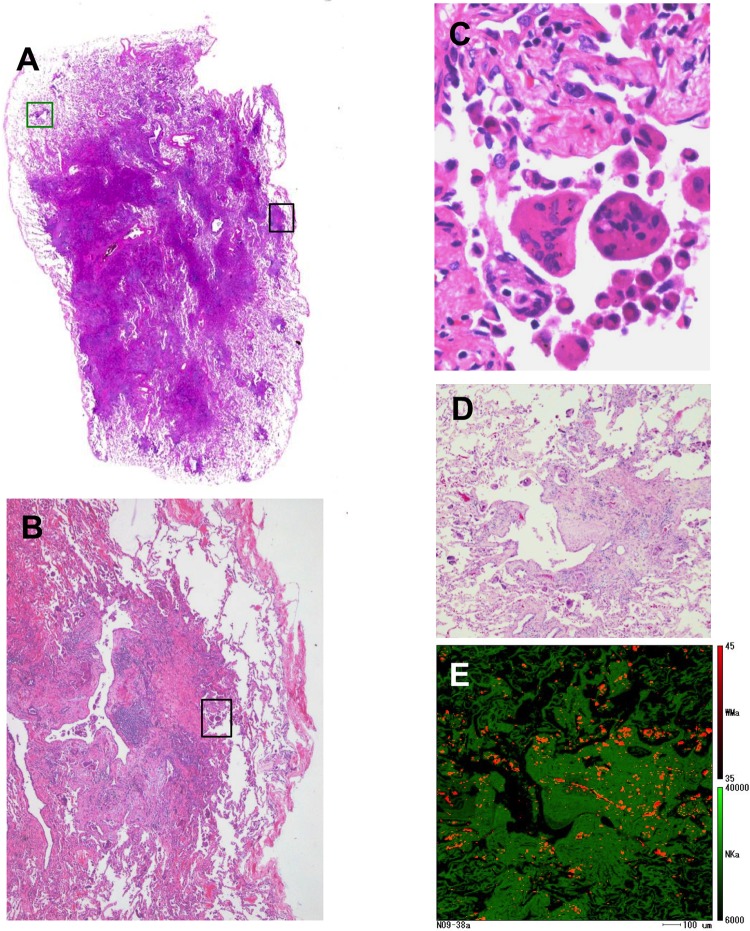

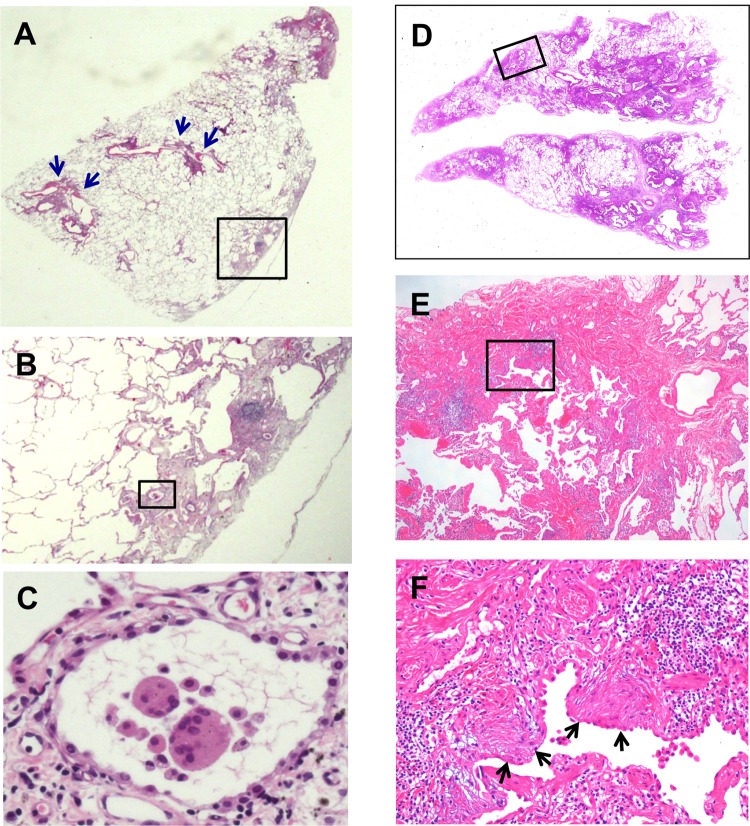

Pathological findings and detected elements in lung tissue of 19 cases are summarised in table 4. Four major histological features were noted in this study: GIP characterised by centrilobular fibrosis (figure 2A,B) and characteristic giant cells showing cannibalism (figure 2C), centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis similar to GIP but without giant cells, UIP pattern characterised by patchy distribution and temporal heterogeneity, and dense fibrosis with fibroblastic foci (figure 3A,B,D–F),12 upper lobe fibrosis characterised with apical scar/cap type fibrosis mainly in the upper lobe.13 In the case of upper lobe fibrosis, the biopsy specimen contained apical cap-like subpleural dense fibrosis composed of airspace fibrosis (intraluminar organisation) with collapse and increased elastic framework. In a postmortem sample taken 4 years later, we recognised remarkable subpleural elastosis with a few cannibalistic giant cells.

Table 4.

Pathological findings and elemental analysis of patients with hard metal lung disease

| Sampling |

Elements detected |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Method | Site(s) | Pathological findings | W | Co | Ta |

| 1 | VATS | rt. S5/S8 | Centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis | + | − | − |

| 2 | VATS | lt. S2/S9 | GIP | + | − | − |

| 3 | TBB/VATS | rt. apex | GIP | + | − | − |

| 4 | VATS | rt. S9 | Centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis | + | − | − |

| 5 | VATS | rt. S4/S9 | GIP | + | − | − |

| 6 | Autopsy | NA | GIP, DAD | + | − | − |

| 7 | VATS | rt. S8 | Centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis | + | + | − |

| 8 | VATS | rt. S4/S6 | GIP | + | − | + |

| 9 | VATS | rt. S2/S6 | GIP | + | + | − |

| 10 | VATS | lt. S1+2/S10 | UIP, GIP | + | − | + |

| 11 | VATS | lt. S1+2/S9 | GIP | + | + | − |

| 12 | Autopsy | NA | GIP, DAD | + | − | − |

| 13 | VATS | lt. S1+2/S6 | GIP | + | − | − |

| 14 | VATS | lt. S4/S9 | GIP, UIP/NSIP? | + | − | + |

| 15 | VATS | rt. S6 | GIP | + | + | − |

| 16 | VATS/autopsy | lt. S1+2/whole | Upper lobe fibrosis | + | − | + |

| 17 | TBB/Lobectomy | –/RLL | UIP | + | − | − |

| 18 | VATS | lt. S1+2/S9 | UIP | + | + | − |

| 19 | VATS | rt. S3/S10 | UIP, centrilobular fibrosis | + | − | + |

DAD, diffuse alveolar damage; GIP, giant cell interstitial pneumonia; NA, not available; NSIP, non-specific interstitial pneumonia; RLL, right lower lobectomy; TBB, trans-bronchial biopsy; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Figure 2.

Representative images of light microscopic findings and electron probe microanalyser with wavelength dispersive spectrometer (EPMA-WDS) of the S6 specimen from case 9 pathologically diagnosed as giant cell interstitial pneumonia. (A–C) The black square area in centrilobular fibrosis is stepwise magnified to show multinucleated giant cells with cannibalism. (A,D) The green square area in the subpleural zone is elementally analysed by EPMA-WDS to show (E) many orange spots corresponding to tungsten. A qualitative coloured image of tungsten distribution is superimposed onto a lung tissue image of amino nitrogen coloured green. Note that tungsten is widely distributed in centrilobular fibrosis as well as the surrounding alveolar walls. Original magnification, (A) panoramic view, (B) ×4, (C) ×60, (D) ×8.

Figure 3.

Representative images of light microscopic findings of a lung specimen from case 10 with hard metal lung disease pathologically diagnosed as usual interstitial pneumonia pattern. (A,B) A low magnification view of the left S1+2 specimen demonstrates a combination of patchy interstitial fibrosis with alternating areas of normal lung and architectural alteration due to chronic scarring or honeycomb change. Note that there are several small bronchioles with mild centrilobular inflammation (blue arrows). (B,C) Multinucleated giant cells with cannibalism are also shown in a stepwise-magnified black square area located in subpleural fibrosis. (D–F) Left S10 specimen from the same patient also shows characteristic fibroblastic foci (black arrows) in the background of dense acellular collagen in a stepwise-magnified square area located in subpleural fibrosis. Original magnification, (A and D) panoramic view, (B) ×2, (C) ×40, (E) ×4, (F) ×20.

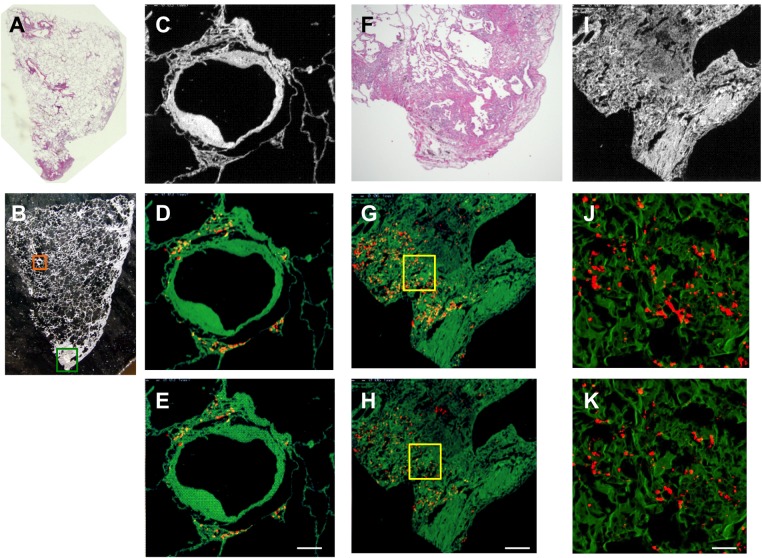

Elemental analyses of lung specimens of GIP and centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis demonstrated that tungsten was mapped almost throughout the centrilobular fibrotic areas (figure 2D,E). Analyses of lung specimens of the UIP pattern by EPMA-WDS revealed that tungsten and tantalum were distributed in the periarteriolar area (figure 4D,E) and in subpleural fibrosis with dense acellular collagen (figure 4G,H,J,K). However, these elements were not accompanied by centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis (figure 4A,B). Lung histopathology in one case showed apical cap-like fibrosis with tungsten deposits detected in the fibrotic region but without GIP.14 In total, elemental analysis by EPMA-WDS detected tungsten but no cobalt or tantalum in 10 patients, tungsten and cobalt in five patients, and tungsten and tantalum in four patients (table 4).

Figure 4.

Representative images of light micrographs and electron probe microanalyser with wavelength dispersive spectrometer (EPMA-WDS) of a lung specimen from case 10 with hard metal lung disease pathologically diagnosed as usual interstitial pneumonia pattern (A). (B,C) An arteriole and its surrounding interstitium (orange square) are elementally analysed by EPMA-WDS to demonstrate that (D) tungsten and (E) tantalum are distributed in the periarteriolar area with little fibrosis. Elemental analysis by EPMA-WDS of subpleural fibrosis with dense acellular collagen (green square in B, F and I) also shows (G and J) tungsten and (H and K) tantalum almost randomly distributed in magnified images (yellow squares in G and H are magnified to show (J) tungsten and (K) tantalum). We did not further analyse the centrilobular pattern or the cannibalistic giant cells shown in figure 3. Note that the distribution of tungsten is not exactly the same as that of tantalum. Original magnification, (A) panoramic view, (B) ×4. Scale bars for the magnification and scan areas for (E), (H) and (K) correspond to 100 μm (0.768×0.768 mm), 200 μm (1.536×1.536 mm) and 25 μm (0.1792×0.1792 mm), respectively.

Comparison of clinical features

We then classified the patients with hard metal lung disease into two groups according to their pathological findings. We grouped GIP and centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis together, because the latter pattern was considered to be a variant of GIP due to the similar distribution of lesions. One patient was pathologically diagnosed as having upper lobe fibrosis. It has such characteristic findings of subpleural, zonal, rather well defined fibrosis with small cysts and honeycomb lesions similar to those of the UIP pattern that we grouped the UIP pattern and upper lobe fibrosis together and named them the fibrosis group. We then compared clinical features between the GIP group and the fibrosis group. The GIP group was younger, had shorter exposure duration, lower serum KL-6, and higher lymphocyte percentage in BAL fluid compared to the fibrosis group (table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of clinical features between giant cell interstitial pneumonia (GIP) group and fibrosis group

| GIP group (n=14) |

Fibrosis group (n=5) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.1±10.8 | 58.6±5.41 | 0.007 |

| Gender (M/F) | 7/7 | 5/0 | 0.106 |

| Exposure duration (months) | 73.0±48.8 | 285.6±140.3 | 0.007 |

| Pneumothorax (+/−) | 6/8 | 2/3 | 1.000 |

| KL-6 (U/mL) | 398.7±189.4 | 710.8±297.7 | 0.023 |

| SP-D (ng/mL) | 260.3±257.5 | 161.0±54.75 | 0.903 |

| PaO2 (Torr) | 84.3±14.3 | 84.4±11.2 | 0.922 |

| PaCO2 (Torr) | 42.8±2.75 | 56.0±34.6 | 0.657 |

| VC, % predicted (%) | 64.4±27.1 | 65.5±24.1 | 0.734 |

| FEV1 (L) | 1.63±0.23 | 1.88±0.32 | 0.537 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 85.4±12.9 | 86.1±2.62 | 0.910 |

| DLco, % predicted (%) | 50.8±16.7 | 57.2±18.8 | 0.371 |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage | |||

| Total cell count (×105/mL) | 3.52±2.41 | 2.26±0.96 | 0.395 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 31.5±23.0 | 8.40±9.08 | 0.015 |

| CD4/8 ratio | 0.76±0.51 | 3.22±4.85 | 0.298 |

DLco, carbon monoxide diffusing capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; KL-6, Krebs von den Lungen 6; SP-D, surfactant protein D; VC, vital capacity.

Discussion

Pathological features of GIP are interstitial pneumonia with centrilobular fibrosis and multinucleated giant cells in the airspaces.15 Sometimes centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis is only noted with few giant cells. EPMA-WDS analysis of lung tissue of hard metal lung disease demonstrated that tungsten was distributed in a relatively high concentration almost throughout the centrilobular fibrosis and in giant cells.7 Comparison of distribution of inflammatory cells and tungsten suggested that inhaled hard metal elements were associated with centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis by CD163 macrophages in cooperation with CD8 lymphocytes. Thus, centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis without giant cells should also be a variant of hard metal lung disease. GIP was also found in Belgian diamond polishers exposed not to hard metal dust, but to cobalt-containing dust, which confirmed that cobalt plays a dominant role in hard metal lung disease.16 Cobalt is a well-known skin sensitiser, causing allergic contact dermatitis; it can also cause occupational asthma.17 Four patients were positive for patch testing for cobalt. Although such patch testing has been claimed to carry some risk of aggravation of disease in the situation with beryllium, cobalt is included in the routine metal allergy test panel and caused no worsening of hard metal lung disease. Hard metal lung disease cases show features of HP with small interstitial granulomas, although well formed granulomas as in chronic beryllium disease are very rarely seen in the disease or in HP. These data suggest that allergic inflammation may be different between hard metal lung disease/HP and berylliosis.

Respiratory symptoms of hard metal lung diseases sometimes improve on holidays and exacerbate during workdays, a pattern resembling symptoms of HP. Histopathology findings in HP may also include centrilobular fibrosis in association with isolated giant cells.18 However, they do not show cannibalism as do those in hard metal lung disease. BAL is the most sensitive tool to detect HP: a marked lymphocytosis with decreased CD4/8 ratio is characteristic of BAL findings.19 BAL findings of patients with hard metal lung disease show increased total cell counts with increased lymphocytes and decreased CD4/CD8 ratio.4 20–22 Reduced CD4/8 ratio is consistent with the findings from immunohistochemistry in the previous study.7 In this study, we found that the percentage of lymphocytes in BAL fluid was increased with a rather low CD4/8 ratio in the GIP group, but not in the fibrosis group.

The UIP pattern is the pathological abnormality associated with various restrictive lung diseases, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Interstitial inflammation and fibrosis in the UIP pattern does not usually involve the centrilobular area and peribronchioles. Three cases, pathologically diagnosed with the UIP pattern, also had centrilobular micronodular opacities shown by HRCT. One patient was pathologically diagnosed as having the UIP pattern and centrilobular fibrosis. Element analysis of the deposition in lung tissues from patients with IPF/UIP usually demonstrates the following elements: Si, Al, Fe and Ti in varying degrees (unpublished data). We found that tungsten accumulated in the periarteriolar area and subpleural fibrosis in lung specimens of the UIP pattern in this study. However, tungsten in the periarteriolar area was hardly associated with any fibrosis or inflammatory cells. These results suggest that individual immune susceptibility/response to inhaled hard metal elements may decide pathological patterns of UIP, GIP or their mixture in varying degrees. Patients develop hard metal lung disease usually after mean exposure duration of more than 10 years. Although most studies have found no relation between disease occurrence and length of occupational exposure, individuals with increased susceptibility may develop hard metal lung disease after relatively short and low levels of exposure. The GIP group was younger and had shorter exposure duration, suggesting that those who had the UIP pattern were individuals with decreased susceptibility. Upper lobe fibrosis was pathologically diagnosed in one patient. Although it is significantly different from the UIP pattern, tungsten in the fibrosis was not associated with inflammation around the element. With regard to the relationship between hard metal elements and surrounding inflammation, upper lobe fibrosis looks similar to the UIP pattern in the other cases.

Liebow first described GIP as a form of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.23 It is now recognised that GIP is pathognomonic for hard metal lung disease.24 Since tungsten and cobalt are only observed within the lungs of subjects who have been exposed to hard metals, the presence of tungsten and/or cobalt in BAL fluid or lung specimens leads to a definite diagnosis of hard metal lung disease. According to the results of elemental analyses in this study, five cases with the UIP pattern or upper lobe fibrosis should be diagnosed as hard metal lung disease. The pathological findings of the UIP pattern demonstrated no physical connection between centrilobular fibrosis and the UIP area, dense fibrosis with fibroblastic foci. Since centrilobular fibrosis is usually irreversible, if GIP evolved to UIP, sequels of centrilobular fibrosis would be somewhat linked to the peripheral UIP lesion. EPMA-WDS analyses of lung specimens of the UIP pattern revealed that tungsten and tantalum in periarteriolar area were not accompanied by centrilobular inflammation/fibrosis as seen in typical GIP. In addition, clinical features of the fibrosis group were different from those of the GIP group. We identified tungsten in subpleural fibrosis with dense acellular collagen from the UIP pattern and in the fibrotic region from apical cap-like fibrosis. Fibrotic reactions of these patients could have caused accumulation of hard metal particles as the scars contract and cut off lymphatic drainage. Those who are not sensitive to hard metal elements, particularly cobalt, might simply have idiopathic UIP or upper lobe fibrosis by accident as everyone with interstitial lung disease and a history of asbestos exposure does not have asbestosis.25 However, microscopic findings of the lung specimen of the UIP pattern included mild centrilobular inflammation and multinucleated giant cells with cannibalism, which could never been seen in idiopathic UIP/IPF. If we find tungsten or cobalt in the biopsies of UIP/fibrosis from the subjects who worked in the hard metal industry, we cannot help but make a diagnosis of hard metal lung disease. Given the present information, we only conclude that the UIP/fibrosis may be induced by hard metal elements, or just a coincidence. Since the incidences of hard metal lung disease and IPF in potentially exposed populations and in the general population are unknown, the probability that someone with hard metal exposure will develop ‘idiopathic’ UIP/IPF is also unknown.

Hard metal lung disease is caused by exposure to cobalt and tungsten carbide. Toxicity stems from reactive oxygen species generation in a mechanism involving both elements in mutual contact.26 Inhaled cobalt and tungsten carbides may cause lung toxicity even in those who are less sensitive to those elements, which can result in lung fibrosis with GIP features. Qualitative elemental analysis of fibrosing lesions in GIP also demonstrated the presence of miscellaneous elements—Al, Si, Ti, Cr and Fe—in addition to tungsten, cobalt and/or Ta.7 Several sources of evidence suggest that environmental agents may have an aetiological role in IPF. A meta-analysis of six case–control studies demonstrated that six exposures—cigarette smoking, agriculture/farming, livestock, wood dust, metal dust and stone/sand—were significantly associated with IPF.27 Metal dust must contain various metal elements. In an EPMA analysis field of the lung biopsy specimen from upper lobe fibrosis, we found tungsten scattered throughout the fibrosis as well as aluminium, silicon and titanium.14 Miscellaneous metal dust inhaled in addition to tungsten and cobalt may cause the UIP pattern in less sensitive individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following doctors for the supply of cases: Dr Y Endo from Nagaoka Chuo General Hospital, Dr M Amano and Dr S Aoki from Showa General Hospital, Dr T Ishiguro from Gifu Municipal Hospital, Dr M Sakai from Saga Social Insurance Hospital, Dr M Tajiri from Kurume University, Dr T Ishida from Niigata Prefectural Central Hospital, Dr K Koreeda from Minami Kyusyu National Hospital, Dr K Okuno from Kasai City Hospital, Dr Y Shimaoka from Nagaoka Red Cross Hospital, Dr K Kashiwada from Nippon Medical School, Dr T Sawada and Dr A Shiihara from Kanagawa Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center, Dr K Tachibana from National Hospital Organisation Kinki-chuo Chest Medical Center, Dr T Azuma from Shinshu University, Dr K Hara and Dr T Ishihara from NTT east corporation Kanto Medical Center, Dr Y Waseda from Kanazawa University, Dr H Ishii from Oita University, Dr H Matsuoka from Osaka Prefectural Medical Center for Respiratory and Allergic Diseases, Dr A Hara from Nagasaki University, Dr O Hisata from Tohoku University, and Dr H Tokuda from Social Insurance Chuo General Hospital. The authors would also like to acknowledge Dr Kouichi Watanabe and Mr Masayoshi Kobayashi of EPMA Laboratory, Center of Instrumental Analysis, Niigata University, who contributed to elemental analysis of lung specimens.

Footnotes

Contributors: JT and HM, elemental analysis. ES, IN and TY, interpretation of the results. MT, ES, YK and AH, pathological study. JT and TT, manuscript preparation; and FS and HA, radiological examination.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: We acquired consent from all treating physicians for each identified case according to the Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies from The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Committee of Ethics, Niigata University, approved the EPMA-WDS study protocol (#396).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Nemery B. Metal toxicity and the respiratory tract. Eur Respir J 1990;3:202–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelleher P, Pacheco K, Newman LS. Inorganic dust pneumonias: the metal-related parenchymal disorders. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108(Suppl 4):685–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takada T, Moriyama H. Hard metal lung disease. In: Huang Y-CT, Ghio AJ, , Maier LA, eds. A clinical guide to occupational and environmental lung diseases respiratory medicine. New York: Springer, 2012:217–30 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison AG, Haslam PL, Corrin B, et al. Interstitial lung disease and asthma in hard-metal workers: bronchoalveolar lavage, ultrastructural, and analytical findings and results of bronchial provocation tests. Thorax 1983;38:119–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cugell DW. The hard metal diseases. Clin Chest Med 1992;13:269–79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anttila S, Sutinen S, Paananen M, et al. Hard metal lung disease: a clinical, histological, ultrastructural and X-ray microanalytical study. Eur J Respir Dis 1986;69:83–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moriyama H, Kobayashi M, Takada T, et al. Two-dimensional analysis of elements and mononuclear cells in hard metal lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:70–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohori NP, Sciurba FC, Owens GR, et al. Giant-cell interstitial pneumonia and hard-metal pneumoconiosis. A clinicopathologic study of four cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13:581–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis WD, Matsui K, Moss J, et al. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: prognostic significance of cellular and fibrosing patterns: survival comparison with usual interstitial pneumonia and desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:19–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katzenstein AL, Myers JL. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical relevance of pathologic classification. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:1301–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moriyama H, Yamamoto T, Takatsuka H, et al. Expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor and its receptor in hepatic granulomas of Kupffer-cell-depleted mice. Am J Pathol 1997;150:2047–60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Thoracic Society Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:646–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiota S, Shimizu K, Suzuki M, et al. [Seven cases of marked pulmonary fibrosis in the upper lobe]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 1999;37:87–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaneko Y, Kikuchi N, Ishii Y, et al. Upper lobe-dominant pulmonary fibrosis showing deposits of hard metal component in the fibrotic lesions. Intern Med 2010;49:2143–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naqvi AH, Hunt A, Burnett BR, et al. Pathologic spectrum and lung dust burden in giant cell interstitial pneumonia (hard metal disease/cobalt pneumonitis): review of 100 cases. Arch Environ Occup Health 2008;63:51–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demedts M, Gheysens B, Nagels J, et al. Cobalt lung in diamond polishers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984;130:130–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nemery B, Verbeken EK, Demedts M. Giant cell interstitial pneumonia (hard metal lung disease, cobalt lung). Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2001;22:435–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Churg A, Muller NL, Flint J, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:201–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Ippolito R, Chetta A, Foresi A, et al. Induced sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage from patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Respir Med 2004;98:977–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okuno K, Kobayashi K, Kotani Y, et al. A case of hard metal lung disease resembling a hypersensitive pneumonia in radiological images. Intern Med 2010;49:1185–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kakugawa T, Mukae H, Nagata T, et al. Giant cell interstitial pneumonia in a 15-year-old boy. Intern Med 2002;41:1007–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forni A. Bronchoalveolar lavage in the diagnosis of hard metal disease. Sci Total Environ 1994;150:69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebow AA. Definition and classification of interstitial pneumonias in human pathology. Prog Respir Res 1975:1–33 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abraham JL, Burnett BR, Hunt A. Development and use of a pneumoconiosis database of human pulmonary inorganic particulate burden in over 400 lungs. Scanning Microsc 1991;5:95–104; discussion 5–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaensler EA, Jederlinic PJ, Churg A. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in asbestos-exposed workers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991;144: 689–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fubini B. Surface reactivity in the pathogenic response to particulates. Environ Health Perspect 1997;105(Suppl 5): 1013–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taskar VS, Coultas DB. Is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis an environmental disease? Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:293–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.