Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study is to describe healthcare utilisation in the last year of life for people in Australia, to help inform health services planning. The methods and datasets that are being used are described in this paper.

Design/Setting

Linked, routinely collected administrative health data are being analysed for all people who died in New South Wales (NSW), Australia's most populous state, in 2007. The data comprised linked death records (2007), hospital admissions and emergency department presentations (2006–2007) and cancer registrations (1994–2007).

Participants

There were 46 341 deaths in NSW in 2007. The initial analyses include 45 760 decedents aged 18 years and over.

Outcome measures

The primary measures address the utilisation of hospital-based services at the end of life, including number and length of hospital admissions, emergency department presentations, intensive care admissions, palliative-related admissions and place of death.

Results

The median age at death was 80 years. Cause of death was available for 95% of decedents and 85% were linked to a hospital admission record. In the greater metropolitan area, where data capture was complete, 83% of decedents were linked to an emergency department presentation. 38% of decedents were linked to a cancer diagnosis in 1994–2007. The most common causes of death were diseases of the circulatory system (34%) and neoplasms (29%).

Conclusions

This study is among the first in Australia to give an information-rich census of end-of-life hospital-based experiences. While the administrative datasets have some limitations, these population-wide data can provide a foundation to enable further exploration of needs and barriers in relation to care. They also serve to inform the development of a relatively inexpensive, timely and reliable approach to the ongoing monitoring of acute hospital-based care utilisation near the end of life and inform whether service access and care are optimised.

Keywords: STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study data will provide powerful information about the hospital-based experiences at the end of life for all people who died in an entire state across a full calendar year, providing a valuable addition to the limited epidemiological information currently available.

The data cannot be used to identify the ‘appropriateness’ of care patterns or care delivery, and the information about palliative care specialist service use was incomplete.

Not all emergency department presentations could be captured and not all cause of death information was available.

The results will provide baseline data for future studies of service access for care towards the end of life, along with an indication of the types of information required to develop a more comprehensive data collection infrastructure.

Introduction

There are more than 45 000 deaths each year in New South Wales (NSW),1 Australia's most populous state. Despite the NSW population of around 7 million people accounting for 33% of the country's population,2 there is little epidemiological information available about healthcare utilisation towards the end of life for these people. This information is important for planning and optimising the availability and appropriateness of healthcare services across NSW. While there is some related information available for other Australian states,3–13 there has been a gap in the evidence base for clinicians and researchers in NSW to develop, implement and monitor patient outcomes.

Worldwide, studies of end-of-life care have covered population groups ranging from small hospital-based samples to all decedents across several countries.14–16 Many studies have focused on place of death,17 palliative care18 and health services use for specific disease subgroups such as cancer.19 20 There are no Australia-wide studies of health services use at the end of life and only two Australian studies have addressed this for all decedents within a State, both covering deaths in Western Australia (WA) around 2002. One study described place of death and, for a subgroup of decedents with terminal illnesses, the use of specialist palliative care.3 The other study analysed hospital costs, but did not report specific numbers of decedents in hospital.4 All other Australian studies of end-of-life care have been restricted to specific disease types, age groups or population subgroups.

Two NSW studies have examined patterns of health service utilisation near the end of life; however, both were restricted to a subgroup of decedents and did not describe presentations to emergency departments (EDs). One study examined the place of death for people dying of cancer in 1999–2003.21 The other study focused on hospital costs for decedents aged 65 years and over who died of any cause in 2002–2003.22

A study of people in WA aged 65 years and older who died between 1984 and 1994 reported the average number of hospital admissions and length of stay in hospital at the end of life.5 Another study described palliative care use for people who died from selected chronic conditions in WA during 2000–2002.6 A more recent study in WA reported on hospitalisations at the end of life for a similar subgroup of decedents who also had an informal primary carer.7

A number of studies from South Australia have addressed epidemiological questions relating to end-of-life care. Two studies of cancer deaths between 1990 and 1999 reported on the utilisation of hospice and palliative care services.8 9 Other studies explored various end-of-life issues using data obtained through the South Australian Health Omnibus survey—an annual government-supported health survey. These included information about: unmet care giving needs10; place of death and its relationship to illness and uptake of specialist palliative care services11; factors associated with specialist palliative care service uptake including its relationship to caregiver perceptions of unmet need12 and outcomes of specialist palliative care services.13 While informative for those specific purposes, these studies did not address utilisation of hospitals or EDs towards the end of life.

The aim of this study is to describe patterns of utilisation of acute hospital-based services by NSW residents during their last year of life using linked, routinely collected administrative health data. It includes all people who died in NSW in 2007. This study will enhance the existing evidence base, enabling us to determine the use of acute hospital-based services by this population including admissions to hospital, time spent in hospital, presentations to ED, types of services received in hospital and place of death. We are also examining variations in use of these services among groups defined by factors including age group, cause of death and geographical area. This will provide information that can form a foundation for further analyses and research studies that aim to address the health services needs of people who are nearing the end of their life in NSW. In this paper, we describe the methods we have used to assemble the study dataset and provide a description of the study cohort.

Methods

Data sources and record linkage

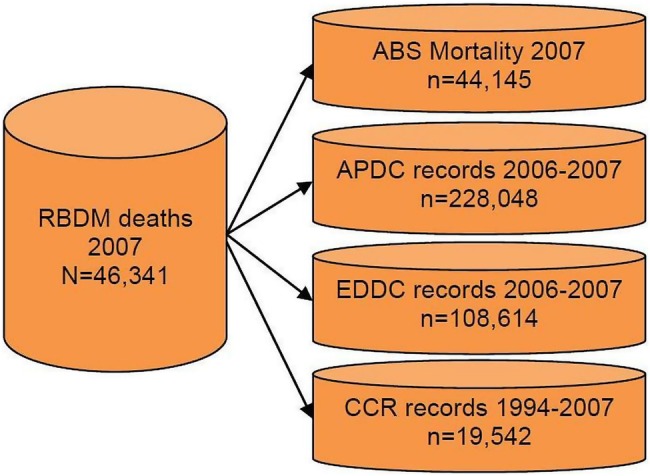

This is a retrospective population-based study using de-identified linked health records. From the NSW Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages (RBDM), we identified all people who died in NSW during the 2007 calendar year. Coded causes of death were obtained for these people from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Mortality data. We also obtained information about their hospitalisations between January 2006 and December 2007 from the NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC), information on their presentations to EDs for the same period through the NSW Emergency Department Data Collection (EDDC), and information on any cancer diagnoses these people had between 1994 and 2007 from the NSW Central Cancer Registry (CCR) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data sources for analysis of the hospital-based experiences of people who died in New South Wales, Australia in 2007.

The RBDM receives notification of all deaths in NSW and the resulting dataset contains date of death and age at death. The ABS Mortality dataset contains coded causes of death and demographic information (eg, sex and area of residence) for all deaths in NSW. We chose to work with data for people who died in 2007 as this was the most recent year for which coded cause of death information was available from the ABS. Further, the ABS releases this information based on the year in which the deaths were registered, not when they occurred, so deaths occurring later in 2007 may not have been included in the data released for 2007. The APDC contains information on all admissions to public, private or repatriation hospitals, private day procedure centres or public nursing homes in NSW, including procedures performed, diagnoses recorded and patients’ demographic characteristics. The data are abstracted from medical records following the patient's discharge from hospital. The EDDC contains information on the majority of emergency department presentations in NSW, including dates, times and departure status. The coverage of the EDDC is described in more detail below. The CCR contains information on all cancers diagnosed in NSW, except for non-melanoma skin cancers, including summary disease stage and patients’ demographic characteristics.

Linkage of records in these datasets was carried out by the Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL),23 using probabilistic matching carried out with ChoiceMaker software (ChoiceMaker Technologies Inc, New York, USA). Privacy was preserved through the linkage process: the CHeReL used personal identifiers for decedents but held no health information, while the researchers received the health information for the decedents but no personal identifiers. Records for all uncertain matches from the linkage process and a sample of ‘certain’ matches and non-matches underwent clerical review by linkage officers at the CHeReL, and approximately 0.4% false-positive and less than 0.5% false-negative linkages were reported.

Characteristics of decedents

Personal characteristics recorded across the data sources included age at death, sex, marital status, country of birth, need for interpreter service and causes of death. Two geographical variables were created, both based on local government area of residence at the time of death: accessibility to services as defined by the Accessibility/Remoteness Index for Australia (ARIA+)24 and socioeconomic status quintile based on the ABS index of relative disadvantage.25 Initial analyses are being restricted to people aged 18 years or more at death, as the experiences of those younger than 18 years (1% of all deaths) were considered likely to be very different to those of the adult population. Decedents younger than 18 years will be studied separately. Cause of death was taken from the ABS ‘underlying cause of death’ field and each person could also have up to 20 contributing causes of death recorded. Cause of death was available as a four-character code using the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10); we summarised these to the standard three-character groupings for analysis.

Measures of hospital-based services utilisation

We are generating indicators of hospital-based services utilisation for each person during the 365 days prior to their death, including the number and length of hospital admissions, the number and length of ED presentations, the amount of time spent in an intensive care unit (ICU), the number of admissions with a palliative care component, procedures recorded in hospital and place of death.

Several different indicators in the APDC are being used to identify palliative care service utilisation. These indicators will reflect two definitions of palliative-related admissions. The first definition, which captures people who were clearly documented as having been seen by a specialist palliative care team, includes admissions that had a specific flag, indicating that the patient saw a palliative team, or admissions to the five stand-alone hospice/inpatient palliative care facilities in the State. The second broader definition includes all admissions potentially related to palliative care, including some decedents who may have received palliative care but not from a specialist team. This group includes those captured by the first definition, together with admissions where the service unit type was a palliative care bed, admissions where the service category or service-related group or a diagnosis code indicated palliative care, and admissions where the patient was flagged as having been referred to a palliative care team or palliative unit or hospice.

Admission to an intensive care unit was flagged when the number of hours spent in intensive care at each admission was recorded in the APDC. The dataset does not allow us to determine whether the person was in an ICU at the time of death or on the day of death, only whether the person spent time in the ICU during an admission.

Deaths in hospitals or EDs are being identified from the arrival/separation status recorded in the APDC and EDDC. The CCR also recorded place of death as in a hospital, hospice, nursing home or the person's home. If the death was not recorded in the APDC or EDDC as being in hospital, we are using place of death recorded in the CCR where available. Deaths occurring on the date of separation from a hospital or ED where status on separation was not ‘died’ are not being classified as deaths in hospital.

We are also investigating a number of markers that have been proposed as potential indicators of ‘aggressive’ care for people who died from cancer.26 Covering the last 30 days of life, these markers include: having an ICU admission; having more than one hospital admission; spending more than 14 days in hospital; and having more than one ED presentation. Earle et al26 proposed other markers of potentially ‘aggressive’ cancer care in the weeks prior to death including receiving chemotherapy in the final 2 weeks, starting a new chemotherapy regimen in the final month, and being admitted to a hospice for fewer than 4 days. However, chemotherapy and hospice admissions were not reliably recorded in the dataset, and so these are not being investigated.

Coverage by the NSW EDDC

The EDDC only contained information for 46% (n=86) of the 185 EDs in NSW during the study period. These EDs accounted for 81% of all ED attendances in that time (J Agland, personal communication, October 2012) and included care provided in all major metropolitan EDs.27 NSW is divided into 15 Local Health Districts (LHDs). The EDDC included 37 of the 39 EDs in the ‘Greater Sydney Area’, comprising the following LHDs: Central Coast, Illawarra Shoalhaven, Nepean Blue Mountains, Northern Sydney, South Eastern Sydney, South Western Sydney, Sydney and Western Sydney. The two EDs in these LHDs not included are relatively small facilities covering less complex cases.27

Eighty-three per cent of adult decedents from the Greater Sydney Area who died in 2007 were linked to at least one record in the EDDC. In the study, we will restrict analyses of ED presentations to the decedents from these LHDs (accounting for 62% of NSW adult deaths) as we believe that they have sufficiently complete information on presentations to the ED. For the decedents in this region who were not linked to the EDDC, we are confident that this was not due to data availability or linkage issues, but rather because these people did not present at an ED during the study period. While the proportion linked to the EDDC was also around 80% for decedents from Hunter New England and Mid North Coast LHDs, there were three and four EDs in the respective LHDs not covered by the EDDC, so these two LHDs were excluded from analyses of ED utilisation as were the other five LHDs, all covering rural and remote areas for which ED data capture was incomplete.

Data analysis

The measures of interest (number of hospital admissions, place of death, etc) are being analysed for all adult decedents and separately for selected groups defined by key patient characteristics (age, place of residence, etc). We are analysing these outcomes using descriptive statistics and multivariable logistic regression. Information about marital status and need for an interpreter service was only available from the APDC and EDDC datasets, so if a decedent did not have linked records in either of these, then this information was not available. We are therefore omitting these variables from analyses where interpretation of the outcome of interest (related to a hospital admission or ED presentation) would require information about persons who were not in these datasets.

We are analysing the data on an admission-by-admission basis, treating each admission record separately. We are also aggregating records with overlapping dates for an individual, considering these admissions to be part of the one overall hospitalisation ‘episode’. Although overlapping dates could reflect a discharge and readmission on the same day, this was relatively rare. Of the multiple admission ‘episodes’ that were identified, 78% involved a transfer from one hospital to another, 18% were due to a change in type of service within the same hospital and only 4% reflected a discharge and readmission on the same day to the same hospital.

The purpose of this paper is to describe the methods of the study and provide descriptive statistics (counts and proportions) for the cohort relating to sociodemographic characteristics and levels of linkage to the datasets of interest. Subsequent publications will report on in-depth analyses for subgroups of the cohort of decedents. All analyses are being carried out in SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Sample size and characteristics

There were 46 341 deaths in NSW in 2007 with 45 760 of these people aged 18 years or more. The results that follow refer to decedents aged 18 years or older. The median age at death was 80 years (IQR 70–87 years). Around 1% of these decedents had no information on sex, country of birth or geographical location of residence, while 13% had unknown marital status and 17% had no information on the need for an interpreter (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of adult decedents in New South Wales in 2007* (n=45 760)

| Number of deaths | Per cent of deaths | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at death | ||

| 18–59 | 5723 | 13 |

| 60–79 | 15 724 | 34 |

| 80–89 | 16 363 | 36 |

| 90+ | 7950 | 17 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 22 430 | 49 |

| Male | 23 120 | 51 |

| Unknown | 210 | 0.5 |

| Country of birth | ||

| Australia | 33 870 | 74 |

| Other | 11 539 | 25 |

| Unknown | 351 | 1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 4120 | 9 |

| Married (including de facto) | 18 268 | 40 |

| Widowed | 14 286 | 31 |

| Separated/divorced | 2949 | 6 |

| Unknown | 6137 | 13 |

| Interpreter required | ||

| No | 36 533 | 80 |

| Yes | 1651 | 4 |

| Unknown | 7576 | 17 |

| Accessibility/remoteness of residence† | ||

| Major cities | 30 908 | 68 |

| Inner regional | 10 993 | 24 |

| Outer regional | 3176 | 7 |

| Remote/very remote | 221 | 0.5 |

| Unknown | 462 | 1 |

| Socioeconomic status‡ | ||

| Most disadvantaged quintile | 9047 | 20 |

| Quintile 2 | 10 210 | 22 |

| Quintile 3 | 10 172 | 22 |

| Quintile 4 | 7879 | 17 |

| Least disadvantaged quintile | 7945 | 17 |

| Unknown | 507 | 1 |

*Excludes 580 decedents aged <18 years and 1 decedent with no age information.

†Based on Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Accessibility/Remoteness Index for Australia.

‡Using population-based quintiles of the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ index of relative disadvantage.

Record linkage

Coded cause of death was available from the ABS for 95% of adults who died in 2007. Of the 2220 decedents who were not linked to records in the ABS Mortality Data, 94% died in December 2007 (representing 59% of all deaths in this month), although around one-third of these people had cause of death information available from the CCR. The vast majority of decedents were linked to records in the hospital or ED datasets, and 38% had a cancer diagnosis recorded in the CCR between 1994 and 2007 (table 2).

Table 2.

Linkage by data source for adult decedents in New South Wales in 2007 (n=45 760)

| Data source | Number of deaths | Per cent of deaths |

|---|---|---|

| Australian Bureau of Statistics (mortality) | 43 540 | 95 |

| Admitted Patient Data Collection 2006–2007 | 38 818 | 85 |

| Emergency Department Data Collection 2006–2007 | 35 554 | 78 |

| Central Cancer Registry 1994–2007 | 17 315 | 38 |

| Not linked to any of the above | 210 | 0.5 |

Causes of death

The most common underlying causes of death were diseases of the circulatory system (34% of all deaths) and neoplasms (29%) (table 3). Excluding people who died in December, due to the relatively large proportion with unknown cause of death, did not substantially alter the distribution of causes of death.

Table 3.

Underlying causes of death for adult decedents in New South Wales in 2007 (n=45 760)

| Cause of death | Number of deaths | Per cent of deaths |

|---|---|---|

| A00-B99: Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | 728 | 2 |

| C00-D48: Neoplasms | 13 441 | 29 |

| D50-D89: Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | 158 | 0.3 |

| E00-E90: Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 1460 | 3 |

| F00-F90: Mental and behavioural disorders | 2015 | 4 |

| G00-G99: Diseases of the nervous system | 1619 | 4 |

| I00-I99: Diseases of the circulatory system | 15 501 | 34 |

| J00-J99: Diseases of the respiratory system | 3718 | 8 |

| K00-K99: Diseases of the digestive system | 1440 | 3 |

| L00-L99: Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 144 | 0.3 |

| M00-M99: Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 334 | 1 |

| N00-N99: Diseases of the genitourinary system | 1069 | 2 |

| Q00-Q99: Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities | 67 | 0.1 |

| R00-R99: Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, no further classification | 334 | 1 |

| V00-Y98: External causes of morbidity and mortality | 2140 | 5 |

| Cause of death not available | 1589 | 3 |

Discussion

This study utilises existing health data collections to describe the use of acute hospital-based services during the last year of life by all adults who died in NSW in 2007. It will be the first study in Australia to report hospitalisation rates for all adult decedents for the whole State, and only the second (and first in NSW) to describe place of death for all decedents state-wide. The study will also describe ED presentations at the end of life for the majority of NSW decedents, giving an information-rich census of the end-of-life experience. Work on this dataset is in progress, including analyses of hospital admissions, time in hospital, ED presentations, place of death and identification of factors related to these and other outcomes of interest. We are investigating these factors in relation to specific causes of death such as cancer and cardiovascular disease, along with the hospital-based experiences towards the end of life for children and very elderly decedents.

There are limitations to this study. Owing to data not being made available, there was no coded cause of death information from the ABS for 59% of those who died in December 2007. However, the distribution of causes of death in December, where the data were available, was very similar to that for all other months, and the CCR data provided cause of death for a large number of cancer deaths where it was not available from the ABS. In addition, the analyses rely on probabilistic record linkage, so it is possible that there were incorrect linkages with hospital or ED records, although the CHeReL estimated that there were only around 0.4% false-positive linkages and less than 0.5% false-negative linkages.

Other limitations include that the EDDC currently does not capture presentations to all EDs in NSW, so we cannot presently provide a ‘whole-of-state’ description of ED presentations during the last year of life. The EDDC is a relatively new data collection that is currently being expanded to include all EDs in NSW. This expansion will benefit future studies using these data and the methods described in this study will be applicable to future datasets with complete coverage of the State. To ensure accuracy in this analysis, however, we are therefore restricting analyses of ED utilisation to decedents living in the geographical area in which we believe almost all ED presentations were captured. As these were predominantly EDs in urban areas, this will limit our ability to comment on potentially important differences in the utilisation of EDs between these and rural settings.

Another limitation is the restriction on ABS data availability. The ABS has limited the release of cause of death information for deaths after 2007. Negotiations are currently underway to re-establish the supply of these data; however, it means that we have to use data that are now up to 7 years old. The annual number of deaths has increased in that time, and while trends may be similar for many conditions and in many situations, it is feasible that differences in patterns of care and practices between that time and now may exist.

In presenting data from this study, we must highlight that there are limitations in the dataset that limit our ability to accurately reflect all service use. The lack of information about palliative care specialist service use and bed use is problematic. Data on specialist palliative care are collected in other Australian jurisdictions, so it is expected that it would be feasible for this to be undertaken in NSW in the future. The similar lack of information about the specific days on which ICU services were accessed also presents problems in relation to considering ICU use at the end of life. Other gaps include the lack of information about place of death within the hospital, and demographic factors that could impact service access and use such as language barriers between health service providers, patients and families. Also, there are currently barriers to linking any of the hospital-based service data to community-based service data, and therefore the former tell only a ‘part of the story’ in relation to overall healthcare utilisation towards the end of life. Importantly, this study will serve to highlight to policy-makers the need to review the data that are routinely collected and to consider which data should be collected to facilitate optimal analyses of health service utilisation towards the end of life.

These data have two further important limitations. There is no subjective, patient, family or carer-reported information in these administrative data that could serve to shed light on these groups’ perceptions of care and whether their needs are met—a vital outcome if, as a society, we are to optimise our healthcare. Also, these data sources cannot be used to identify the ‘appropriateness’ of care patterns or care delivery. While the markers of potentially ‘aggressive’ cancer care were developed by Earle et al26 in the USA and have been explored in various populations since and will be explored in this dataset in subsequent analyses, it must be acknowledged that these markers may capture care that is quite ‘appropriate’. Thus, although these markers could be used as baseline information to prompt further investigations into ‘appropriateness’, these should not be interpreted as definite indicators of inappropriate or even ‘aggressive’ care. For example, admission to intensive care—sometimes deemed as inappropriate towards the end of a life-limiting illness—may indeed be quite appropriate under some circumstances. In addition, we do not have any information on the patients where this ‘aggressive’ care was successful and death was averted. The identification of palliative care service utilisation is also an important consideration in relation to whether care options are optimal. Unfortunately, as discussed previously, documentation of the utilisation of these services is not comprehensive as the dataset did not include complete documentation of hospital access to palliative care or information about any access to palliative care provided in the community setting. Therefore, it does not represent the full array of palliative care service utilisation.

Despite these potential limitations, the data we are using will provide powerful population-based information about the hospital-based end-of-life experiences of all adults who died across the entire State. Decedents aged less than 18 years, who comprise only 1% of all deaths, will be studied as a separate cohort.

The data being used in this study are routinely collected for other purposes and the linkage process is established and ongoing, which makes it possible to routinely update the analyses being undertaken in this study to monitor activity over time, provided the coded cause of death information is available. Such data will enable an analysis of the effect of relevant characteristics (eg, cause of death and geographical location of residence) on acute hospital-based service utilisation. The gaps in the data, for example, in relation to palliative care services, highlight areas where consideration could be given to additions to routinely collected data to more accurately reflect service use over time.

Importantly, the data described in this study will provide a necessary foundation for asking an important ‘next set of questions’. Such questions, to be addressed in subsequent studies, would require a data collection approach other than record linkage. These could include investigating the reasons behind any disease-specific or regional differences identified in acute hospital-based services utilisation, whether some population groups encounter more barriers than others in service access, and how all of this relates to the needs of individuals and their ‘subjective’ experiences of the health system—the latter being an area totally absent from routinely collected data. With the answers to this next set of questions, the planning of health services can be based around the goal of meeting clearly quantified needs of all individuals with serious illness, including those who are nearing the end of their life, addressing identified barriers to access to services and optimising care at this often difficult time of life for patients, families and carers.

Conclusions

The data from this study will provide reliable information about the experiences of those who died in NSW in 2007. These data can also serve to inform a relatively inexpensive, timely and reliable approach to the ongoing monitoring of the hospital-based end-of-life experiences of all adults in NSW. Also, the study will highlight gaps in existing routine data collections that may also serve to inform future data collection strategies and thus allow for more comprehensive and informative future analyses and assessment of all aspects of healthcare access and quality. In summary, this study will provide a foundation from which to develop an efficient data collection infrastructure and will also provide baseline data for future studies of service access for care towards the end of life in NSW and other jurisdictions in Australia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

JMI and JLP conducted this research with funding support from the Cancer Institute New South Wales Academic Chairs Program.

Footnotes

Contributors: DLO, JMI and MP conceived and designed the study. DLO and DEG acquired the data. DEG analysed the data with input from DLO and JMI. All authors were involved in drafting the protocol and revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Cancer Institute NSW via a NSWOG Project Support Application. The views here are those of the authors and were not influenced by the funding bodies.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: New South Wales Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (Australia).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages—Deaths [website] http://www.bdm.nsw.gov.au/resources/statsinfo.pdf (accessed 29 Oct 2013).

- 2.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Demographic Statistics. Cat. no. 3101.0. Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNamara B, Rosenwax L. Factors affecting place of death in Western Australia. Health Place 2007;13:356–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calver J, Bulsara M, Boldy D. In-patient hospital use in the last years of life: a Western Australian population-based study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2006;30:143–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brameld KJ, Holman CD, Bass AJ, et al. Hospitalisation of the elderly during the last year of life: an application of record linkage in Western Australia 1985–1994. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:740–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenwax LK, McNamara BA. Who receives specialist palliative care in Western Australia—and who misses out. Palliat Med 2006;20:439–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenwax LK, McNamara BA, Murray K, et al. Hospital and emergency department use in the last year of life: a baseline for future modifications to end-of-life care. Med J Aust 2011; 194:570–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt R, McCaul K. Coverage of cancer patients by hospice services, South Australia, 1990 to 1993. Aust N Z J Public Health 1998;22:45–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt RW, Fazekas BS, Luke CG, et al. The coverage of cancer patients by designated palliative services: a population-based study, South Australia, 1999. Palliat Med 2002;16:403–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Currow DC, Ward A, Clark K, et al. Caregivers for people with end-stage lung disease: characteristics and unmet needs in the whole population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2008; 3:753–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Currow DC, Burns CM, Abernethy AP. Place of death for people with non-cancer and cancer illness in South Australia: a population-based survey. J Palliat Care 2008;24:144–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Currow DC, Agar M, Sanderson C, et al. Populations who die without specialist palliative care: does lower uptake equate with unmet need? Palliat Med 2008;22:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Fazekas BS, et al. Specialized palliative care services are associated with improved short- and long-term caregiver outcomes. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:585–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Morton SC, et al. Methodological approaches for a systematic review of end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2005;8(Suppl 1):S4–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.George LK. Research design in end-of-life research: state of science. Gerontologist 2002;42:86–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mularski RA, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, et al. A systematic review of measures of end-of-life care and its outcomes. Health Serv Res 2007;42:1848–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broad JB, Gott M, Kim H, et al. Where do people die? An international comparison of the percentage of deaths occurring in hospital and residential aged care settings in 45 populations, using published and available statistics. Int J Public Health 2013;58:257–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies E, Higginson IJ. Palliative care: the solid facts. World Health Organisation, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ 2006;332:515–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang ST, McCorkle R. Determinants of place of death for terminal cancer patients. Cancer Invest 2001;19:165–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabor B, Tracey E, Glare P, et al. Place of death of people with cancer in NSW. A population based study. Sydney, Australia: Cancer Institute NSW, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kardamanidis K, Lim K, Da Cunha C, et al. Hospital costs of older people in New South Wales in the last year of life. Med J Aust 2007;187:383–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centre for Health Record Linkage [website] http://www.cherel.org.au (accessed 29 Oct 2013).

- 24.Australian Population and Migration Research Centre Measuring remoteness: accessibility/remoteness index of Australia (ARIA). Revised Ed. Occasional Paper New Series No. 14. http://www.adelaide.edu.au/apmrc/research/projects/category/aria.html (accessed 29 October 2013).

- 25.Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2008. An introduction to socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), 2006. Cat. no. 2039.0. Canberra, Australia; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, et al. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3860–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NSW Ministry of Health. Role delineation levels of emergency medicine, 3rd Edition. Sydney, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.