Abstract

Objectives

Vasodilation of the peripheral arteries during reactive hyperaemia depends in part on release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells. Previous studies mainly employed a fingertip tonometric device to derive pulse wave amplitude (PWA) and PWA hyperaemic changes. An alternative approach is based on photoplethysmography (PPG). We sought to evaluate the correlates of digital PPG PWA hyperaemic responses as a measure of peripheral vascular function.

Design

The Flemish Study on Environment, Genes and Health Outcomes (FLEMENGHO) is a population-based cohort study.

Setting

Respondents were examined at one centre in northern Belgium.

Participants

For this analysis, our sample consisted of 311 former participants (53.5% women; mean age 52.6 years; 43.1% hypertensive), who were examined from January 2010 until March 2012 (response rate 85.1%).

Primary outcome measures

Using a fingertip PPG device, we measured digital PWA at baseline and at 30 s intervals for 4 min during reactive hyperaemia induced by a 5 min forearm cuff occlusion. We performed stepwise regression to identify correlates of the hyperaemic response ratio for each 30 s interval after cuff deflation.

Results

The maximal hyperaemic response was detected in the 30–60 s interval. The explained variance for the PPG PWA ratio ranged from 9.7% at 0–30 s interval to 22.5% at 60–90 s time interval. The hyperaemic response at each 30 s interval was significantly higher in women compared with men (p≤0.001). The PPG PWA changes at 0–90 s intervals decreased with current smoking (p≤0.0007) and at 0–240 s intervals decreased with higher body mass index (p≤0.035). These associations with sex, current smoking and body mass index were mutually independent.

Conclusions

Our study is the first to implement the new PPG technique to measure digital PWA hyperaemic changes in a general population. Hyperaemic response, as measured by PPG, is inversely associated with traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as male sex, smoking and obesity.

Keywords: population, endothelial function, vasodilation, photoplethysmography

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study is the first to implement the new photoplethysmography (PPG) technique to measure digital pulse amplitude hyperaemic changes in a sample of a general population. A finger PPG is a low-cost and operator-independent technique compared with ultrasound in the assessment of peripheral vascular function.

Under strictly controlled conditions, we were able to demonstrate a good intersession reproducibility of the hyperaemic response as measured by the PPG technique.

Our sample size was smaller compared with other studies. On the other hand, the correlates of hyperaemic response were as expected and constitute an internal validation of the PPG technique in assessment of digital vascular function.

Further research including clinical and prospective epidemiological studies is required to validate the PPG technique for non-invasive assessment of endothelial function and prediction of cardiovascular outcome, respectively.

Introduction

Endothelial dysfunction, a marker of reduced nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, contributes to atherosclerosis and the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease.1 In humans, endothelial dysfunction precedes the development of clinically apparent atherosclerosis in individuals with cardiovascular risk factors.2 Vasodilation of the peripheral arteries during reactive hyperaemia after ischaemia depends in part on the release of NO from endothelial cells in response to increased shear stress.3 This physiological response allows the non-invasive assessment of endothelial vasomotor function which can be measured based on the flow-mediated dilation (FMD) of the brachial artery4 or on the fingertip pulse amplitude hyperaemic response.3 5 6 Previous studies mainly applied fingertip peripheral arterial tonometry (PAT) to derive pulse wave amplitude (PWA) and, therefore, the pulse amplitude changes during hyperaemia.3 5 6 Another approach to derive information about the arterial pulse wave is based on photoplethysmography (PPG).7 This optical technique enables detecting blood volume changes in microvascular beds during hyperaemia.7 We sought to evaluate the correlates of digital PPG pulse amplitude hyperaemic responses as a measure of peripheral arterial function in a sample of a general population.

Materials and methods

Design and sample

From August 1985 until December 2005, we identified a random population sample stratified by sex and age from a geographically defined area in northern Belgium.8 The seven municipalities gave listings of all inhabitants sorted by address. Households, defined as those who lived at the same address, were the sampling unit. We numbered households consecutively, and generated a random-number list by using SAS random function. Households with a number matching the list were invited. The initial participation rate was 78.0%.

The FLEMENGHO study is an ongoing longitudinal population study and, therefore, the participants were repeatedly visited at home and examined at a local examination centre. From January 2010 until March 2012 a scheduled follow-up examination also included measurement of digital vascular function with the PPG technique. From 444 invited participants for this examination, we obtained informed written consent from 378 participants (response rate 85.1%). We excluded 43 participants with cardiac dysrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation, pacemaker and frequent extrasystole. Because the PPG pulse amplitude was of insufficient quality to assess vascular function (n=14) or because the hyperaemic test was discontinued (n=10) we discarded a further 24 participants. Thus, the number of participants statistically analysed totaled 311.

Determination of PPG pulse amplitude

The participants refrained from smoking, heavy exercise and drinking alcohol or caffeine-containing beverages for at least 3 h before the test. No medication was taken on the day of the examination. We studied digital vascular function in an air-conditioned room at constant temperature around 22°C. To attain a cardiovascular steady-state before starting the test, the participants had rested for at least 20 min in the supine position. Since peripheral vasoconstriction is correlated with the surrounding temperature, before the test, special care was taken to keep the fingertips temperature around 35°C. The blood pressure was the average of five auscultatory readings, obtained with a standard sphygmomanometer. The blood pressure measurement was performed on the arm that served as control.

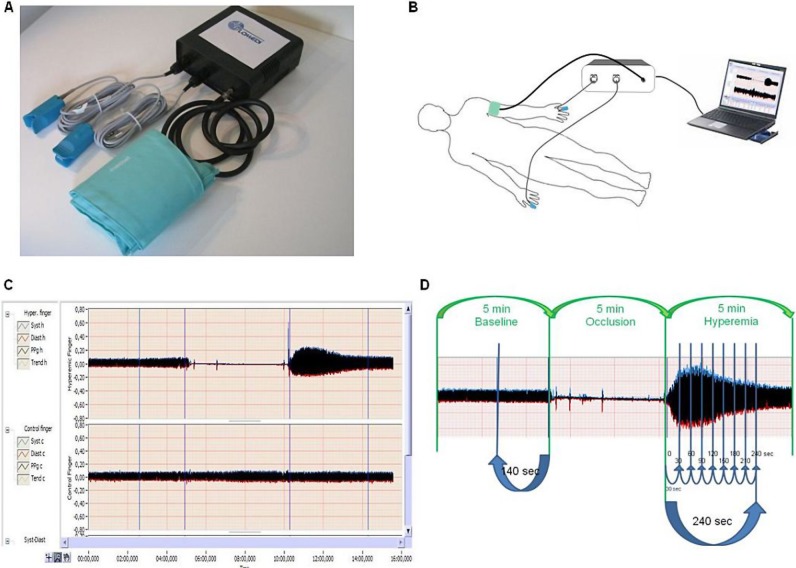

Digital pulse amplitude was measured with a PPG device (FLOMEDI Company, Brussels) transmitting infrared light at a wavelength of 940 nm and positioned on the tip of each index finger. Digital output from the PPG device was recorded through an analogue-to-digital converter (10 bit, sampling frequency 250 Hz). We expressed the amplitude of the PPG PWA signal in arbitrary units. To determine the amplitude changes of the digital pulse curve in response to hyperaemia, we used a protocol as described by Hamburg et al.6 As shown in figure 1C,D, baseline PPG pulse amplitude was registered at each of the two index fingertips for at least 5 min to ensure a stable baseline PPG signal. For the analysis, we used PPG pulse amplitude that was measured for last 2 min 20 s. Next, arterial flow was interrupted for 5 min by an inflatable cuff placed on the proximal forearm with an occlusion pressure of 200–220 mm Hg (around 50 mm Hg above the participant's systolic pressure). Complete cessation of blood flow to the hand is verified by the absence of a PPG signal from the occluded arm. After cuff deflation, we analysed the PPG pulse amplitude at both fingers using a computerised, automated algorithm (FLOMEDI Company, Brussels) that provided the averaged pulse amplitude for each 30 s interval up to 4 min (see the PPG pulse tracking in figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Image showing a system incorporating two photoplethysmography (PPG) devices transmitting infrared light, analogue-to-digital converter and forearm pressure cuff. (B) Showing the position of cuff and two PPG devices during the test. (C and D) showing recorded pulse amplitude tracing. In the arm undergoing hyperaemia (C, top tracing; and D), baseline amplitude is recorded. During cuff inflation, flow is occluded and restores after cuff release (hyperaemic period). In the contralateral control finger (C, bottom tracing), flow continues throughout, and pulse amplitude undergoes minimal changes.

For each 30 s interval, the response of the PPG PWA to hyperaemia was calculated from the hyperaemic fingertip as the ratio of the postdeflation PPG pulse amplitude to the baseline amplitude (PAht/PAh0, where PA is the pulse amplitude, h is the hyperaemic finger, t is time interval and 0 is baseline). To obtain the PPG pulse amplitude ratio we divided PAht/PAh0 ratio by the corresponding ratio at the control hand (PAct/PAc0, where c is the control finger).

To determine the intersession reproducibility of the hyperaemic response, we analysed PPG ratios measured on two different occasions in five participants. We determined the absolute and relative biases of the averaged PPG pulse amplitude ratios per each 30 s time interval between the two sessions as well as 95% limits of agreement between sessions. Absolute and relative biases between the two sessions were calculated according to Bland and Altman's method as (x1−x2) versus averaged and (100(x1−x2)/averaged) versus averaged, respectively. The absolute and relative biases of the averaged PPG pulse amplitude ratios at each time interval between the two sessions were 0.062 (95% CI –0.10 to 0.23) and 3.29% (95% CI –8.8% to 15.4%), respectively.

Other measurements

At the examination centre, trained study nurses administered a questionnaire to collect detailed information on each participant's medical history, smoking and drinking habits, and intake of medications. Hypertension was a blood pressure of at least 140 mm Hg systolic or 90 mm Hg diastolic (average of five consecutive auscultatory readings at the examination centre) or the use of antihypertensive drugs. Body mass index was weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres. Overweight was a body mass index between 25 and 30 kg/m². Obesity was a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher.

Statistical methods

For database management and statistical analysis, we used SAS software, V.9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The central tendency and the spread of the data are reported as mean±SD. Departure from normality was evaluated by Shapiro-Wilk's statistic and skewness by computation of the coefficient of skewness, that is, the third moment about the mean divided by the cube of the SD. We compared means and proportions by means of a sample t test and by the χ2 test, respectively. Significance was p<0.05 on two-sided test.

We performed single and stepwise multiple regression to assess the independent correlations of the PPG pulse amplitude ratio during each 30 s interval with sex, age, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, heart rate, body mass index, current smoking, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, haematocrit, blood glucose, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drug treatment and history of ischaemic heart disease. We set the p values for variables to enter and to stay in the regression models at 0.10.

Results

Characteristics of participants and PPG pulse amplitude

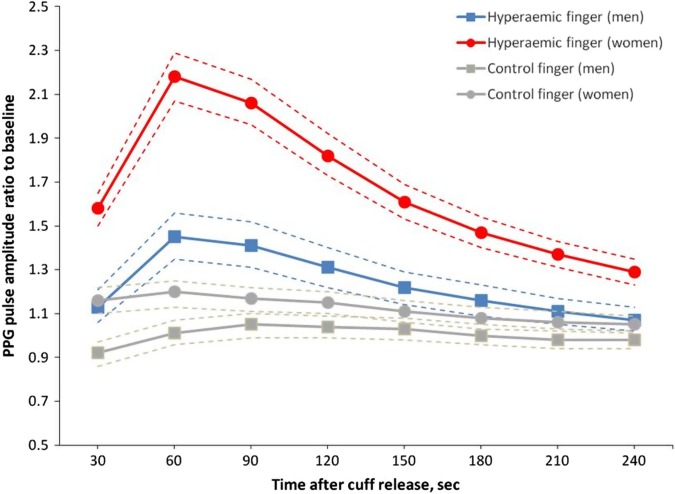

The participants included 154 (53.5%) women and 134 (43.1%) patients with hypertension of whom 78 (25.1%) were on antihypertensive drug treatment. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics and PPG pulse amplitude measures of the study participants by sex. In this cohort, women had lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure and higher heart rate than men, less often reported alcohol consumption and had no history of ischaemic heart disease. The geometric means of the baseline PPG amplitude were 7.3 (5–95% centiles: 2.7–25.9) and 9.3 (5–95% centiles: 3.9–25.3) at the hyperaemic and control finger, respectively. We observed a high correlation between values of the baseline PPG amplitude recorded at both fingers (r=0.89, p<0.0001). As shown in figure 2, after forearm cuff deflation, the ratio of the PPG pulse amplitude to baseline rose rapidly in the hyperaemic fingertip, with maximal response occurring in the 30–60 s interval, whereas the changes of PPG amplitude in the control finger were minimal. Table 1 lists the mean values of the postdeflation PPG pulse amplitude ratio at each 30 s interval by sex. The hyperaemic response at each 30 s interval was significantly higher in women compared with men (table 1). In both women and men, the maximal hyperaemic response was detected in the 30–60 s interval.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Clinical measurements |

PPG pulse amplitude measures |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Women (n=154) | Men (n=157) | p Value | Characteristics | Women (n=154) | Men (n=156) | p Value |

| Anthropometrics | PPG ratio | ||||||

| Age, years | 53.51±12.2 | 51.8±14.5 | 0.26 | Time intervals (s) | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.3±4.0 | 27.3±3.7 | 0.03 | 0–30 | 1.43 (0.87 to 2.02) | 1.27 (0.83 to 1.84) | 0.002 |

| Systolic pressure, mm Hg | 125.5±15.4 | 131.4±14.3 | 0.0006 | 30–60 | 1.93 (1.08 to 2.86) | 1.46 (1.00 to 2.13) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic pressure, mm Hg | 80.4±8.0 | 84.5±9.5 | <0.0001 | 60–90 | 1.84 (1.10 to 2.50) | 1.37 (0.97 to 1.93) | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 66.5±10.2 | 62.4±9.9 | 0.0003 | 90–120 | 1.64 (1.09 to 2.16) | 1.27 (0.93 to 1.79) | <0.0001 |

| Questionnaire data | 120–150 | 1.49 (1.06 to 2.01) | 1.20 (0.92 to 1.59) | <0.0001 | |||

| Current smoking, n (%) | 28 (18.2) | 18 (11.5) | 0.10 | 150–180 | 1.38 (1.00 to 1.84) | 1.16 (0.89 to 1.46) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 39 (25.3) | 94 (59.9) | <0.0001 | 180–210 | 1.30 (0.98 to 1.65) | 1.14 (0.87 to 1.43) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 5 (3.3) | 4 (2.6) | 0.72 | 210–240 | 1.24 (0.95 to 1.65) | 1.11 (0.87 to 1.33) | <0.0001 |

| Treated for hypertension, n (%) | 38 (24.7) | 40 (25.5) | 0.87 | ||||

| β-blockers, n (%) | 18 (11.7) | 23 (14.7) | 0.44 | ||||

| ACE or ARB, n (%) | 12 (7.8) | 15 (9.6) | 0.58 | ||||

| Diuretics or CCB, n (%) | 22 (14.3) | 19 (12.1) | 0.57 | ||||

| History of IHD, n (%) | 0 (0) | 7 (4.5) | 0.008 | ||||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.2±1.00 | 5.0±0.96 | 0.037 | ||||

| Lipid lowering agents, n (%) | 10 (6.5) | 8 (5.1) | 0.60 | ||||

Values are mean (±SD), mean (10–90%) or number of participants (%).

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; CCB, calcium channel blockers; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; PPG, photoplethysmography.

Figure 2.

Photoplethysmography (PPG) pulse amplitude response for the hyperaemic and control finger in women (circles) and men (squares). Women had more pronounced responses than men. Symbols are means, dashed line—95% CI.

Determinants of PPG pulse amplitude ratio

We performed stepwise regression to assess the independent correlations of the hyperaemic response for each 30 s interval after cuff deflation with sex, age, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, heart rate, body mass index, current smoking, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, haematocrit, blood glucose, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drug treatment, and history of ischaemic heart disease. With age forced in the models, the explained variance for the PPG pulse amplitude ratio ranged from 9.7% at 0–30 s interval to 22.5% at 60–90 s time interval (table 2). The PPG PWA changes throughout 0–240 s intervals significantly decreased with male sex (p≤0.0004) and with body mass index (p≤0.017). The hyperaemic response at 0–90 s intervals decreased with current smoking (p≤0.0007). These associations with sex, body mass index and current smoking were mutually independent. In addition, the PPG pulse amplitude ratio at 30–60 s interval decreased with total cholesterol, but this association only reached borderline significance (p=0.045; table 2). Blood glucose was also selected as an independent determinant of the PPG ratio (table 2), but overall impact of this covariable is relatively small (explained about 1.5% of total variability). Moreover, blood glucose was not a significant determinant of the maximal peak of hyperaemic response which occurs at 30–60 s and 60–90 s intervals.

Table 2.

Correlates of PPG ratios selected by stepwise regression

| Parameters | PPG ratio |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time intervals (s) | ||||||||

| 0–30 | 30–60 | 60–90 | 90–120 | 120–150 | 150–180 | 180–210 | 210–240 | |

| Regression statistic | ||||||||

| Model R2 (%) | 9.7 | 21.4 | 22.5 | 19.8 | 19.2 | 16.3 | 13.2 | 12.2 |

| Age (+10 years)* | ||||||||

| β±SE | 0.014±0.020 p=0.45 |

−0.0007±0.028 p=0.98 |

0.005±0.025 p=0.85 |

0.004±0.019 p=0.85 |

0.007±0.017 p=0.68 |

−0.0008±0.014 p=0.95 |

0.004±0.012 p=0.72 |

0.002±0.011 p=0.91 |

| Partial r2 (%) | 0.02 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Female | ||||||||

| β±SE | 0.16±0.05 p=0.0004 |

0.49±0.68 p<0.0001 |

0.46±0.061 p<0.0001 |

0.35±0.050 p<0.0001 |

0.26±0.041 p<0.0001 |

0.20±0.035 p<0.0001 |

0.14±0.031 p<0.0001 |

0.12±0.03 p<0.0001 |

| Partial r2 (%) | 3.9 | 13.6 | 16.0 | 15.1 | 13.5 | 12 | 7.7 | 6.1 |

| Current smoking (0,1) | ||||||||

| β±SE | −0.30±0.07 p=0.0004 |

−0.39±0.09 p<0.0001 |

−0.29±0.085 p=0.0007 |

– | – | – | – | – |

| Partial r2 (%) | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Body mass index (+1 kg/m²) | ||||||||

| β±SE | −0.014±0.007 p=0.017 |

−0.027±0.009 p=0.003 |

−0.032±0.008 p<0.0001 |

−0.025±0.007 p<0.0001 |

−0.022±0.005 p<0.0001 |

−0.018±0.005 p<0.0001 |

−0.015±0.004 p=0.0002 |

−0.013±0.004 p=0.0008 |

| Partial r2 (%) | 1.7 | 3.0 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 3.5 |

| Total cholesterol (+1 mmol/L) | ||||||||

| β±SE | – | −0.068±0.034 p=0.045 |

– | – | – | – | – | – |

| Partial r2 (%) | – | 1.1 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Blood glucose (+1 mmol/L) | ||||||||

| β±SE | 0.10±0.04 p=0.013 |

– | – | 0.07±0.04 p=0.026 |

0.06±0.03 p=0.034 |

– | 0.05±0.02 p=0.027 |

0.06±0.02 p=0.006 |

| Partial r2 (%) | 1.9 | – | – | 1.3 | 1.2 | – | 1.4 | 2.2 |

Values are mutually adjusted partial regression coefficients ±SE. *Age was forced into all models. The covariables considered in stepwise models included sex, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, heart rate, body mass index, current smoking, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, haematocrit, blood glucose, antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drug treatment, and history of ischaemic heart disease.

LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PPG, photoplethysmography.

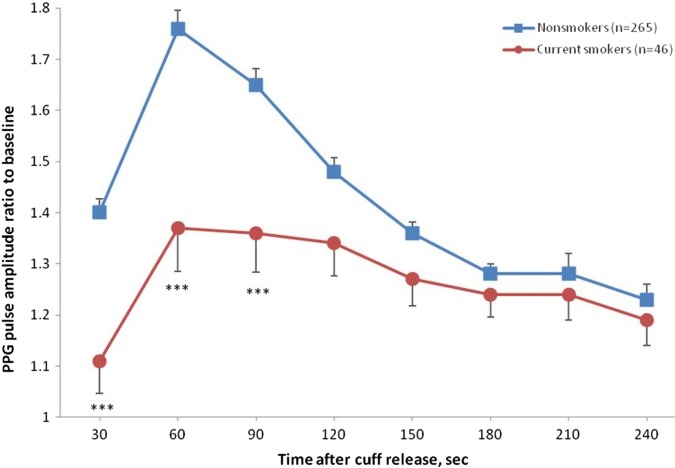

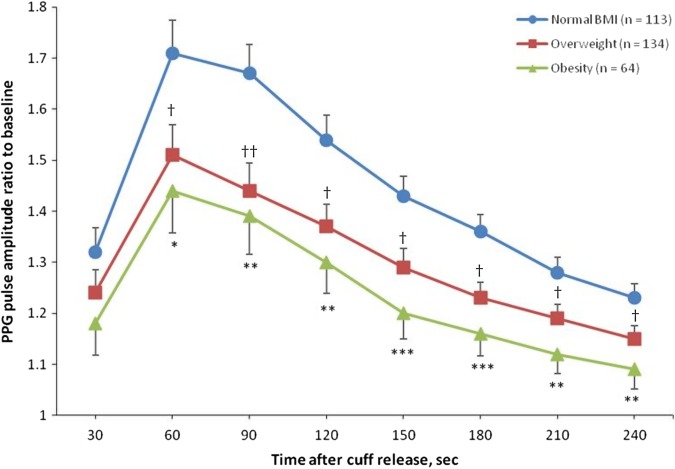

Figure 3 illustrates the hyperaemic responses by the smoking status while adjusted for important covariables. The maximal hyperaemic response in the 30–60 s interval was significantly lower in current smokers compared with non-smokers (1.37 vs 1.76; p<0.0001). Figure 4 shows the adjusted PPG pulse amplitude hyperaemic responses in participants, divided into three categories according to their body mass index. In overweight (n=134; 1.51±0.060) and obese (n=64; 1.44±0.082) participants the maximal hyperaemic response was significantly lower compared with lean participants (n=113; 1.71±0.064).

Figure 3.

Photoplethysmography (PPG) ratio of pulse amplitude for each 30 s time interval after cuff deflation to the baseline pulse amplitude divided by the corresponding ratio in the control finger in smokers and non-smokers participants. Smokers had significantly lower response throughout the 0–120 s postdeflation intervals. Symbols are means and SE. Models are adjusted for sex, age, body mass index, total cholesterol and blood glucose. ***p<0.001 versus non-smokers.

Figure 4.

Photoplethysmography (PPG) ratio of pulse amplitude for each 30 s time interval after cuff deflation to the baseline pulse amplitude divided by the corresponding ratio in the control finger in participants with normal body mass index (BMI), overweight (25 kg/m2≤BMI<30 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI≥30 kg/m2). Symbols are means and SE. Models are adjusted for sex, age, smoking, total cholesterol and blood glucose. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus lean participants. †p<0.05, ††p<0.01, versus lean participants.

Discussion

In our cohort recruited from a population study, we evaluated the relationship between PPG pulse amplitude hyperaemic response, a non-invasive measure of peripheral microcirculation and cardiovascular risk factors. We observed a time-dependent increase in digital PPG pulse amplitude that peaked in the 30–60 s interval after induction of reactive hyperaemia. In keeping with the literature,6 9–11 we found that PPG pulse amplitude hyperaemic response was higher in women than in men and in non-smokers than smokers. Moreover, digital vasodilator function as measured by the PPG technique inversely correlated with body mass index.

Endothelial function is often estimated non-invasively by vascular reactivity tests. Several methods are available to study endothelial function in the peripheral macrocirculation (conduit arteries) and microcirculation (resistance arteries and arterioles).2 12 Measurement of the brachial artery diameter before and after 5 min of occlusion of the arterial flow to the forearm is the most widely used test to assess endothelium-dependent vasodilation.4 13 14 The change in arterial diameter gives a measure of FMD. This technique, however, is operator dependent, is costly and requires a long postprocessing time. Measurement of microcirculatory reactive hyperaemia can be assessed by digital pulse amplitude measured by applanation tonometry5 6 or PPG.15 16 Lund17 described the potential of the PPG technique for the assessment of vasodilation by using this technique to measure haemodynamic response to nitroglycerin. Moreover, Theunissen et al18 observed in divers an increase in circulating NO after successive breath-hold dives. This increase in circulating NO level was associated with higher hyperaemic response measured using the same PPG device as in our study.

Both techniques for assessment of digital vascular function are non-operator dependent, and the equipment is an order of magnitude less expensive than for ultrasonography. However, the tonometry method might be more expensive as compared to the PPG technique because of additional costs associated with changeable plethysmographic probes. Furthermore, the digital tonometry procedure is more complicated and less comfortable for patients because it requires attachment of a pneumoelectrical tube to an additional pneumatic digital cuff which should be constantly inflated during the test.

We observed similar digital PPG pulse amplitude changes during the hyperaemic response compared with results from studies using the finger applanation tonomtery-based method.6 10 11 In the Framingham study,6 10 similar to our study, the ratio of the digital pulse amplitude to baseline rose rapidly in the hyperaemic fingertip after forearm cuff deflation, and then slowly decreased towards baseline. However, we detected the maximal hyperaemic response in the 30–60 s interval, whereas in the Framingham study the pressure amplitude ratio was highest in the 60–90 s interval. The difference in the time of maximal hyperaemic response between the Framingham study and our report might be related to the fact that finger PAT measures pressure changes while PPG measures changes of the relative amount of blood volume.

We observed the relations between the hyperaemic PPG pulse amplitude response and cardiovascular risk factors. In our current study and in other community-based studies,6 10 11 men had a less pronounced hyperaemic response than women, which is probably in part attributable to physiological differences in vessel diameter and wall thickness between the sexes. In line with other studies,6 10 11 which used the PAT technique to evaluate digital vascular function, we demonstrated a significant inverse association between PPG amplitude changes and smoking, obesity and total cholesterol. The mechanism underlying these associations might be related to the fact that exposure to cigarette smoke and metabolic risk factors causes impairment of NO production and an increase of oxidative stress and proinflammatory reaction that leads to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis.19 We also tested the influences of antihypertensive and antihyperlipidaemic treatment on the hyperaemic PPG pulse amplitude response, which were not significant (results not shown). The observed association between the PPG PWA ratio and blood glucose during some time intervals might be related to the optic technique which we used in our study.

Similar to other studies, in which finger applanation tonometry was used to assess the digital vascular function,10 we did not observe a significant relation between hyperaemic PPG pulse amplitude changes and age. On the other hand, previous studies reported lower hyperaemic response as assessed by FMD with advancing age.13 14 Differences in the age-related hyperaemic responses between microcirculatory and macrocirculatory reactivity might explain these divergent findings.9 Moreover, recent studies demonstrated that brachial and digital measures of vascular function were uncorrelated with each other.10 20 It was suggested that FMD and PAT provide distinct information regarding vascular function in conduit versus smaller digital vessels. In our study we also did not observe the difference in hyperaemic response between patients with hypertension and normotensive participants. Similar finding was observed in another epidemiological study10 that used applanation tonometry in assessing microvascular function. We could speculate that the PPG reactive hyperaemia index (microvasculature) is more sensitive to metabolic factors, especially body mass index, smoking and total cholesterol and less sensitive to systemic haemodynamic factors such as high blood pressure.

The present study must be interpreted within the context of its potential limitations and strengths. First, PPG pulse amplitude registration is prone to measurement error due to higher variability in comparisons with the FMD technique.21 On the other hand, assessment of the hyperaemic PPG PWA changes requires little training and is operator independent. Moreover, under strictly controlled conditions, we were able to demonstrate a good intersession reproducibility of the hyperaemic response as measured by the PPG techniques. Second, placing the occlusion cuff above the site of hyperaemic response measurement might evoke a dilatory response that is related in part to ischaemia and, therefore, is not entirely mediated by NO. Moreover, the sex difference in the hyperaemic response observed in our study might be in part attributable to physiological differences in vessel diameter (allometric differences) and, therefore, could not also entirely be explained by low NO realise in men. Further studies should account for the differential response to hyperaemia between men and women. Third, our sample size was smaller compared with other studies.10 11 On the other hand, the correlates of hyperaemic response were as expected and constitute an internal validation of the PPG techniques in assessment of digital vascular function. Fourth, as shown in table 2, in our study, we could explain only around 20% of variability of the PPG PWA ratios by traditional cardiovascular risk factors. The remaining variability might be influenced by genetic factors, inflammatory processes or other confounders that we did not consider in our study. Moreover, in our opinion, it is important to demonstrate in prospective studies that the hyperaemic response as assessed by the PPG technique might be an independent predictor of cardiovascular events.

In conclusion, our study is the first to implement the PPG technique to measure digital pulse amplitude hyperaemic changes in a sample of a general population. We demonstrated that measurement of the hyperaemic response by the PPG technique might be a useful tool in the detection of peripheral microvascular dysfunction associated with smoking and obesity, while accounting for the differential hyperaemic response between men and women. Further research including clinical and prospective epidemiological studies is required to validate the PPG technique for non-invasive assessment of endothelial function and prediction of cardiovascular outcome, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the expert assistance of Linda Custers, Marie-Jeanne Jehoul, Daisy Thijs and Hanne Truyens (Leuven, Belgium).

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, and gave final approval for the final version of the manuscript. TK, EVV and JK drafted the manuscript.

Funding: The European Union (grants HEALTH-2011-278249-EU-MASCARA, HEALTH-F7-305507-HoMAGE, and ERC Advanced Grant-2011-294713-EPLORE) and the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen, Ministry of the Flemish Community, Brussels, Belgium (grants G.0734.09, G.0880.13 and G. 0881.13) gave support to the Research Unit Hypertension and Cardiovascular Epidemiology.

Competing interests: GS and DJ work at FLOMEDI, a spin-off company (Spin Off In Brussels—Innoviris) of the Technical Department of the Haute Ecole Paul Henri Spaak.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of the University of Leuven approved the Flemish Study on Environment, Genes and Health Outcomes (FLEMENGHO).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data Sharing Statement: Data and documentation for the FLEMENGHO study are available at the Study Coordination Office, Research Unit Hypertension and Cardiovascular Epidemiology, University of Leuven.

References

- 1.Vita JA. Endothelial function. Circulation 2011;124:e906–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flammer AJ, Anderson T, Celermajer DS, et al. The assessment of endothelial function: from research into clinical practice. Circulation 2012;126:753–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nohria A, Gerhard-Herman M, Creager MA, et al. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of digital pulse volume amplitude in humans. J Appl Physiol 2006;101:545–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faulx MD, Wright AT, Hoit BD. Detection of endothelial dysfunction with brachial artery ultrasound scanning. Am Heart J 2003;145:943–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuvin JT, Patel AR, Sliney KA, et al. Assessment of peripheral vascular endothelial function with finger arterial pulse wave amplitude. Am Heart J 2013;146:168–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamburg NM, Keyes MJ, Larson MG, et al. Cross-sectional relations of digital vascular function to cardiovascular risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117:2467–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen J. Photoplethysmography and its application in clinical physiological measurement. Physiol Meas 2007;28:R1–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuznetsova T, Herbots L, López B, et al. Prevalence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in a general population. Circ Heart Fail 2009;2:105–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunner H, Cockcroft JR, Deanfield J, et al. Endothelial function and dysfunction. Part II: association with cardiovascular risk factors and diseases. A statement by the Working Group on Endothelins and Endothelial Factors of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens 2005;23:233–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamburg NM, Palmisano J, Larson MG, et al. Relation of brachial and digital measures of vascular function in the community: the Framingham heart study. Hypertension 2011;57:390–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnabel RB, Schulz A, Wild PS, et al. Noninvasive vascular function measurement in the community: cross-sectional relations and comparison of methods. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:371–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lekakis J, Abraham P, Abraham P, et al. Methods for evaluating endothelial function: a position statement from the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Peripheral Circulation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2011;18:775–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, et al. Clinical correlates and heritability of flow-mediated dilation in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2004;109:613–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nawrot TS, Staessen JA, Fagard RH, et al. Endothelial function and outdoor temperature. Eur J Epidemiol 2005;20:407–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zahedi E, Jaafar R, Ali MA, et al. Finger photoplethysmogram pulse amplitude changes induced by flow-mediated dilation. Physiol Meas 2008;29:625–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millasseau SC, Ritter JM, Takazawa K, et al. Contour analysis of the photoplethysmographic pulse measured at the finger. J Hypertens 2006;24:1449–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lund F. Digital pulse plethysmography (DPG) in studies of the hemodynamic response to nitrates—a survey of recording methods and principles of analysis. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1986;59:79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theunissen S, Guerrero F, Sponsiello N, et al. Nitric oxide-related endothelial changes in breath-hold and scuba divers. Undersea Hyperb Med 2013;40:135–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steffen Y, Vuillaume G, Stolle K, et al. Cigarette smoke and LDL cooperate in reducing nitric oxide bioavailability in endothelial cells via effects on both eNOS and NADPH oxidase. Nitric Oxide 2012;27:176–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin BJ, Gurtu V, Chan S, et al. The relationship between peripheral arterial tonometry and classic measures of endothelial function. Vasc Med 2013;18:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donald AE, Charakida M, Cole TJ, et al. Non-invasive assessment of endothelial function: which technique? J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:1846–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.