Abstract

Background

Metabolic disturbances, obesity and life-shortening cardiovascular morbidity are major clinical problems among patients with antipsychotic treatment. Especially two of the most efficacious antipsychotics, clozapine and olanzapine, cause weight gain and metabolic disturbances. Additionally, patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders not infrequently consume alcohol. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) has shown to improve glycaemic control and reduce alcohol intake among patients with type 2 diabetes.

Objectives

To investigate whether the beneficial effects of GLP-1 analogues on glycaemic control and alcohol intake, in patients with type 2 diabetes, can be extended to a population of pre-diabetic psychiatric patients receiving antipsychotic treatment.

Methods and analysis

Trial design, intervention and participants: The study is a 16-week, double-blinded, randomised, parallel-group, placebo-controlled clinical trial, designed to evaluate the effects of the GLP-1 analogue liraglutide on glycaemic control and alcohol intake compared to placebo in patients who are prediabetic, overweight (body mass index ≥27 kg/m2), diagnosed with a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder and on stable treatment with either clozapine or olanzapine. Outcomes: The primary endpoint is the change in glucose tolerance from baseline (measured by area under the curve for the plasma glucose excursion following a 4 h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test) to follow-up at week 16. The secondary endpoints include changes of dysglycaemia, body weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, secretion of incretin hormones, insulin sensitivity and β cell function, dual-energy X-ray absorption scan (body composition), lipid profile, liver function and measures of quality of life, daily functioning, severity of the psychiatric disease and alcohol consumption from baseline to follow-up at week 16. Status: Currently recruiting patients.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained. Before screening, all patients will be provided oral and written information about the trial. The study will be disseminated by peer-review publications and conference presentations.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01845259, EudraCT: 2013-000121-31.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study is a double-blinded, randomised, parallel-group, placebo-controlled clinical trial, designed to evaluate the effects of the GLP-1 analogue liraglutide on glycemic control (measured by area under the curve for the plasma glucose excursion following a 4 h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test) in patients treated with either clozapine or olanzapine.

The study duration is only 16 weeks.

The study has no third treatment arm for comparing liraglutide to one of the two established add-on treatments for antipsychotic induced weight gain and metabolic abnormalities--that is, metformin or topiramate.

The effect of liraglutide on alcohol consumption is evaluated without requiring a certain weekly minimum amount of alcohol consumption.

Introduction

Metabolic disturbances, overweight and obesity among patients with antipsychotic treatment are major clinical problems,1 2 which most likely result from the interaction of medication, genes and lifestyle factors, such as physical inactivity and high fat diet.3 However, the mechanisms underlying antipsychotic metabolic adverse effects are incompletely understood.4

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)-based therapy was introduced to the market for treatment of type 2 diabetes in 2006.5 GLP-1 is an incretin hormone, which is secreted from endocrine L-cells of the small intestine in response to nutrients in the gut lumen.6 GLP-1 plays a central role in the regulation of glycaemic control. It conveys an insulinotropic effect via GLP-1 receptors on the β cells of the pancreas and inhibits the secretion of glucagon from the α cells of the pancreas, which together lower the blood glucose level.7 Both of these effects are strictly glucose dependent. The effects are more pronounced at higher levels of blood glucose and the effect ceases as blood glucose reaches values below 4–5 mmol/L.6 Therefore, stimulation of the GLP-1 receptor keeps the blood glucose at normal levels without increasing the risk of hypoglycaemia.6 Naturally occurring GLP-1 is rapidly degenerated within minutes by dipeptidyl peptidase 4. Liraglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1R), has a 97% homology with naturally occurring GLP-1 hormone, but has a significantly longer half-life (12–14 h), which makes it useful for diabetic treatment.5

Antipsychotic medications are often associated with body weight increase and metabolic disturbances.1–4 Psychiatric patients on antipsychotic treatment, especially those who are overweight or obese, and/or have metabolic disturbances, are often encouraged to increase physical activity. Studies including patients with type 2 diabetes have shown that different types of exercise interventions with supervised training have positive effects on glycaemic control.8 Exercise improves the aerobic capacity and muscular strength, which is often related to fat loss, increased muscle mass, increased cardiovascular fitness and improved glycaemic control. Exercise-induced fat loss and increase in muscle mass may improve glycaemic control and insulin sensitivity in those patients, even in the absence of an absolute weight loss.8 However, in clinical practice, exercise interventions in patients with antipsychotic treatment have often proven to be difficult and may be without pronounced or sustained effect.9–11 Another possibility includes instructions about healthier food intake. This has proven efficacious in some patients, but not in others, and there exists a large group of patients, where healthy lifestyle interventions have not proven to be very efficacious.9–11 In patients treated with a weight-increasing antipsychotic, another possibility would be to shift treatment to a compound with less weight-increasing potential.12 13 However two of the most potent weight-inducing antipsychotics, clozapine and olanzapine, are also two of the most efficacious antipsychotic compounds, and especially clozapine is often used to treat patients resistant to other antipsychotics.14 Consequently, switching antipsychotic treatment is often not possible in these cases.

In a recent meta-analysis of 32 studies on antiobesity adjunction drug treatment, 13 different drug treatments were investigated for a total of 1482 patients with antipsychotic-related weight gain: metformin, nizatidine, topiramate, amantadine, fluoxetine, reboxetine, sibutramine, rosiglitazone, dextroamphetamine, d-fenfluramine, famotidine, orlistat and metformin+sibutramine. Only five of these agents were found to be superior to placebo, that is, metformin, topiramate, fenfluramine, sibutramine and reboxetine.15 Three of these compounds, fenfluramine, sibutramine and reboxetine, have since been removed from the market due to adverse effects leaving only two evidence-based augmentation agents for clinical use, that is, metformin and topiramate. Both compounds cause approximately 2.5–3 kg weight loss compared to placebo.15 Nevertheless, remarkably little is known about metabolic advantages of these two add-on agents, and most studies were small.15

Taken together, there exists a large and important group of patients with antipsychotic treatment, who are in urgent need for medical interventions to improve their metabolic status, so that risk factors for life-shortening cardiovascular morbidity can be reduced. In this context, studies have shown that non-psychiatric patients with type 2 diabetes treated with GLP-1R agonists improve body weight and glycaemic control.16 It is of note, the idea to use metformin in patients with non-diabetes treated with antipsychotic was also triggered by data showing that metformin was capable of mitigating the weight-inducing effects of other antidiabetic medications in patients with diabetes.

In addition, patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders not infrequently have comorbid alcohol addiction.17 The well-established effect of GLP-1 analogues on food reward seems to be driven by two key mesolimbic brain structures, which are involved in the rewarding properties of food as well as drugs of abuse, including alcohol.18 To this effect, very recent preclinical data demonstrated the inhibitory effects of the GLP-1R exendin-4 on alcohol-mediated behaviour in rodents.18 Moreover, the GLP-1 analogue liraglutide was reported to reduce alcohol intake in patients with type 2 diabetes.19

On the basis of the identified medical need and the promising data of GLP-1R in patients with type 2 diabetes, we aim to investigate whether these beneficial findings on glycaemic control, and secondarily on alcohol intake can be extended to psychiatric patients treated with antipsychotics.

Methods and analysis

Overview

The present study is a 16-week, double-blinded, randomised, parallel-group, placebo-controlled clinical trial, designed to evaluate the effects of liraglutide or placebo in 100 patients, who are prediabetic, overweight (body mass index (BMI), ≥27 kg/m2), diagnosed with a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder and on stabile treatment with either clozapine or olanzapine. The trial will be carried out at the Psychiatric Centre Copenhagen and nearby psychiatric centres in close collaboration with the Diabetes Research Division, Copenhagen University Hospital Gentofte, Denmark. To be eligible for participation in the study, patients will undergo a pretreatment evaluation to screen them according to inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Age ≥18 and ≤65 years

Clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizotypal disorder or paranoid psychosis according to the criteria of International Classification of Diseases (ICD10, WHO) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV, the American Psychiatric Association)

Stable antipsychotic treatment with either clozapine or olanzapine for at least 6 months (without dose change for at least 30 days)

Stable comedications for at least 30 days

Stable weight (defined as less than 5% change in weight over the past 3 month before inclusion)

BMI ≥27 kg/m2

Dysglycaemia: impaired fasting glucose (IFG), that is, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level from 6.1 to 6.9 mmol/L and/or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), that is, 2 h glucose levels of 7.8 to 11 mmol/L after a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and a FPG<7 mmol/L

Informed oral and written consent

Exclusion criteria

Type 1 or 2 diabetes with glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) >6.5%

Compulsory treatment

Women of childbearing potential who are pregnant, breastfeeding or have intention of becoming pregnant or are not using adequate contraceptive measures

Participants treated with corticosteroids or other hormone therapy (except oestrogens)

Any active substance abuse or dependence for the past 6 months (except for nicotine)

Impaired hepatic function (liver transaminases >2 times upper normal limit)

Impaired renal function (se-creatinine>150 μM and/or macroalbuminuria)

Impaired pancreatic function (acute or chronic pancreatitis and/or amylase >2 times upper normal limit)

Cardiac problems defined as decompensated heart failure (NYHA class III or IV), unstable angina pectoris and/or myocardial infarction within the past 12 months

Uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure >180 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure >100 mm Hg)

Any condition that the investigator feels would interfere with trial participation

Receiving any investigational drug within the past 3 months

Use of weight-lowering pharmacotherapy within the preceding 3 month

Patient enrolment and randomisation

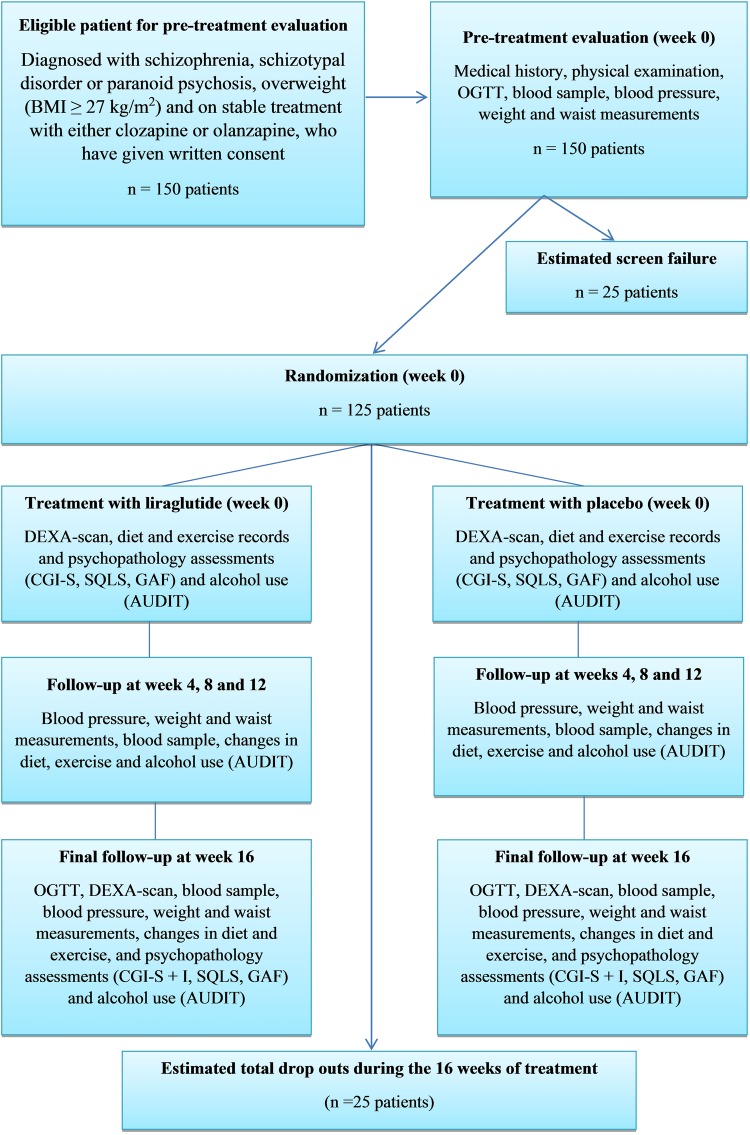

It is estimated that a total of 150 patients, who are overweight (BMI≥27 kg/m2), diagnosed with a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder and on stable treatment with either clozapine or olanzapine, will be screened. The estimated screening failure rate is 15–20% and consequently we expect 125 patients to be randomised and included in the study. The expected number of dropouts is difficult to estimate, since to our knowledge similar interventions with daily subcutaneous injections have not been performed before among psychiatric patients. In a study by Astrup et al,7 16 of 90 patients (17.8%) in the liraglutide 1.8 mg group withdrew over the 20-week trial period. We expect the withdrawal rate to be a little higher in our patient population over time, but this effect is most likely counteracted by the shorter study duration. Consequently, we expect a dropout rate of maximum 20% in our study population over the 16- week trial period, that is, a maximum of 25 of 125 patients will dropout during 16 weeks of treatment resulting in about 100 patients completing the trial (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Completion or trial termination for any reason will be fully documented in the Case Record Form. Patients are free to withdraw from the trial at any time without providing reason(s) for withdrawal and without prejudice to further treatment. The reason for withdrawal could be a withdrawal of consent, treatment failure, adverse event(s), pregnancy discovered during the trial, significant worsening (Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement (CGI-I) score of 6 or 7 (much or very much worse), change in the dosing of olanzapine or clozapine of more than 20%, or loss to follow-up. Data from dropouts will be included in data analysis. Patients withdrawing from the trial should be encouraged to undergo the same final evaluations as patients completing the trial.

The study consists of a pretreatment evaluation, followed by a 16-week treatment period, where patients are randomised to treatment with either daily subcutaneous liraglutide or placebo. Patients will be randomised to treatment with a 3 mL prefilled liraglutide pen-injector containing 6 mg/mL liraglutide, or a 3 mL prefilled liraglutide placebo pen-injector. The randomisation will be carried out by use of sealed opaque envelopes containing the randomisation code. Novo Nordisk will be responsible for labelling and blinding the 3 mL prefilled liraglutide pen-injector containing 6 mg/mL liraglutide and the 3 mL prefilled liraglutide placebo pen-injector before beginning the treatment period and for generating the randomisation code. An emergency code will be kept at the Psychiatric Centre Copenhagen, allowing the code to be broken if a patient develops an adverse reaction that requires knowledge of the treatment.

Treatment protocol

Before screening, all patients will be provided oral and written information about the trial, including the most common adverse events, and the procedures involved in the study. The total duration of the trial for each patient is 16 weeks. Each patient will attend regular visits (every 4 weeks) at the clinic in order to draw blood samples, record changes in diet exercise and alcohol intake, evaluate psychopathology ratings and side effects and measure body weight and waist circumference. Antipsychotic medication and possible IGF/IGT/dysglycaemic history will also be obtained (see figure 1).

Blood analyses

At every visit, routine blood samples will be drawn, to make sure that the patients do not have any serious adverse effect to the treatment and to measure liver function, triglycerides, cholesterol levels and HbA1c.

A 75 g-OGTT)

A 75 g OGTT will be performed at baseline and after 16 weeks of treatment in all participants. Seventy-five grams of water-free glucose dissolved in 300 mL water is to be ingested during the first 5 min of the test. Blood is sampled from a cannula inserted in an antecubital vein before oral intake of the glucose load and at specific times hereafter. At each time-point, blood is drawn for serum/plasma analyses for glucose, insulin, c-peptide, glucagon, intact and total GLP-1 and GIP, respectively. During both experimental days, the hand on the cannula site is wrapped in a heating blanket (42°C) throughout the test. Details are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Blood samples during OGTT

| Time (min) | Plasma glucose (mL) | GLP-1 (intact; mL) | GLP-1 (total; mL) | Glucagon (mL) | GIP (mL) | Insulin/c-peptide (mL) | Extra controls (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −15 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| −10 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 0 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 5 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 10 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 15 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 20 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 30 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 40 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 50 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 60 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 90 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 120 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 150 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 180 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

| 240 | 0.200 | 0.700 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2 | 4 | 3.5 |

GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Dual-energy X-ray absorption scan

Dual-energy X-ray absorption (DEXA) scan will be performed at baseline and after 16 weeks of treatment in all participants. The DEXA scan will be used to measure total fat mass and fat percentage after 10 h of fasting, to decrease large variations in hydration status.

Rating scales

To assess the level of psychopathology and alcohol use during the trial, a number of different rating scales will be used. The focus of the rating scales are, quality of life (The Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (SQLS)), daily functioning ( Global Assessment of Function (GAF)), the disease severity (CGI—severity+improvement (CGI-S+I)) and alcohol consumption (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)).

Liraglutide treatment

Liraglutide/liraglutide placebo, 1.8 mg is administered subcutaneously once daily from day 15 onwards for the remainder of the treatment period after a 14-day fixed titration schedule (days 1–7: 0.6 mg liraglutide/liraglutide placebo; days 8–14: 1.2 mg liraglutide/liraglutide placebo; day 15 and rest of the study: 1.8 mg liraglutide/liraglutide placebo). Patients who do not tolerate up-titration to 1.8 mg liraglutide will remain on the highest tolerable dose of liraglutide. The patients are instructed in injection technique. Compliance and adverse events are noted during the entire period. If the patient cannot self-inject the trial medication, an identified caregiver, also blinded to the treatment, will assist.

Non-pharmacological treatment

Throughout the trial, patients will receive oral and written counselling about diet and exercise in accordance with the recommendations and guidelines from The Danish National Board of Health (https://www.sundhed.dk/borger/sundhed-og-livsstil/). Furthermore, changes in diet and exercise will be recorded every 4 weeks during the trial.

Statistical analysis

All analyses will be performed using the modified intention-to-treat principle on participants who were randomised and received at least one dose of the trial compound (liraglutide or liraglutide placebo). Missing data will be imputed using the last-observation-carried-forward method. Analyses will be performed using SPSS, with α set at 0.05 and two-sided testing.

All continuous outcomes, that is, change in metabolic parameters, weight, body composition parameters, alcohol use, etc, will be analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) from baseline to last observation endpoint. In case relevant baseline demographic, illness or treatment parameters differ significantly between the two groups, these parameters will be included in an ANOVA model. Categorical outcomes, that is, shift from obesity, overweight, hyperglycaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, etc, to the next lower risk category at last observed endpoint, will be analysed using χ² analyses. In case relevant baseline demographic, illness or treatment parameters differ significantly between the two groups, these parameters will be included in a multivariate logistic regression analysis model.

The primary outcome measure was used for the sample size calculation. Based on unpublished data from the study: “‘The Impact of Liraglutide on Glucose Tolerance and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Women With Previous Pregnancy-induced Diabetes,” the expected baseline total area under the curve (AUC) for the plasma glucose (PG) excursion following an OGTT, an α of 5%, a power of 90%, and with values of 1695 (SD 158) in the intervention and 1800 (SD 158) in the control group, the estimated sample size was 96 patients (48 patients in each arm).

Endpoints

The primary endpoint

The primary endpoint is the change in glucose tolerance from baseline (measured by AUC for the PG excursion following a 4 h 75 g OGTT) to follow-up at week 16 or to last observation, if study participation is stopped earlier.

The secondary endpoints

Secondary endpoints include changes of dysglycaemia (IFG, IGT, combined IFG/IGT or diabetes), changes in body weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, secretion of incretin hormones, insulin sensitivity and β cell function, evaluated by homoeostatic model assessment, DEXA scan (body composition), lipid profile, liver function and measures of quality of life, daily functioning, severity of the psychiatric disease and alcohol consumption (in patients with alcohol consumption at baseline) from baseline to follow-up at week 16 or to last observation, if study participation is stopped earlier.

Dissemination

Before screening, all patients will be provided oral and written information about the trial, including the most common adverse events, and the procedures involved in the study.

We considered a longer trial than 16 weeks in order to determine the longer term effects of liraglutide on body weight and metabolic status. However, this would likely have resulted in a higher sample size as dropout rates increase with the duration of the trial. In addition, recruitment could have been affected too, as patients may be less likely to commit for a longer term study. We also considered following patients after stopping the treatment at 16 weeks, in order to assess the durability and speed of the loss of efficacy. However, this would have increased the budget and would be premature, as we believe that this information is only valuable once a significant benefit of liraglutide has been established. We further considered adding a third arm and comparing liraglutide to one of the two established add-on treatments for antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic abnormalities, that is, metformin or topiramate. However, adding a third arm would have increased the complexity and cost of the trial considerably and we considered this also premature, as efficacy of liraglutide would have to be demonstrated first before considering an active comparator trial.

A definite weakness of this study is the need for the daily subcutaneous injection of liraglutide. However, this is a proof of concept study. Should robust efficacy be demonstrated, this would provide the necessary stimulus to invest in the development of an orally administered formulation of liraglutide or a related GLP-1 analogue. A further weakness is that we will assess the effect of liraglutide on alcohol consumption without requiring a minimum alcohol-intake in all participants. Although this will reduce the power to show an effect, the change in alcohol consumption is only a secondary outcome and restricting participants to those using alcohol would have reduced eligible patients for this study. Moreover, we also deliberately excluded patients with substance abuse or addition, as marked alcohol use can interfere with the primary outcome, insulin resistance, and as substance abuse has been associated with decreased treatment adherence.

Conclusions

The present trial aims to evaluate the effects on glycaemic control following 16 weeks of treatment with liraglutide or placebo in 100 patients, who are prediabetic, overweight, diagnosed with a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder and on treatment with either clozapine or olanzapine. Results of this first study of its kind are expected to determine whether liraglutide is effective in improving dysglycaemia and other metabolic parameters as well as alcohol use in patients on antipsychotic medication.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TV and AF-J designed the study and have been involved in reviewing and revising the manuscript. LV, JJH, CUC, PO and AK made contributions to conception and design of the trial and have been involved in reviewing and revising the manuscript. JRL has contributed to the design of the study and drafted the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Novo Nordisk and Mental Health Services Capital Region of Denmark. The study is an independent investigator and University-initiated study. The authors have received an unrestricted grant from Novo Nordisk including the liraglutide medication, the liraglutide placebo as well as the injection pens. In addition we received a grant from Capital Region Psychiatry Research Group.

Competing interests: JRL and AF-J have received research support from Novo Nordisk for the present work. LV has also received an unrestricted grant from Novo Nordisk for another ongoing study. AK and PO have nothing to disclose. JJH has consulted for Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novo Nordisk and Roche. CUC has received personal fees from Actelion, Alexza, AstraZeneca, Biotis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Desitin, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Gerson Lehrman Group, Glaxo Smith Kline, IntraCellular Therapies, Lundbeck, Medavante, Medscape, Merck, Novartis, Ortho-McNeill/Janssen/J&J, Otsuka, Pfizer, ProPhase, Roche, Schering-Plough, Sepracor/Sunovion, Takeda, Teva and Vanda as well as grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen/J&J and Otsuka. Tina Vilsbøll has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Sanofi, and Zealand Pharma, and is a member of the Advisory Boards of Novo Nordisk, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Bristol-Myers Squibb/AstraZeneca.

Ethics approval: The trial was approved by the ethics committee on human research and will be carried out in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.De HM, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry 2011;10:52–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De HM, Detraux J, van WR, et al. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012;8:114–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krane-Gartiser K, Breum L, Glumrr C, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Danish psychiatric outpatients treated with antipsychotics. Nord J Psychiatry 2011;65:345–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Correll CU, Lencz T, Malhotra AK. Antipsychotic drugs and obesity. Trends Mol Med 2011;17:97–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holst JJ. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiol Rev 2007;87:1409–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vilsboll T, Krarup T, Madsbad S, et al. Both GLP-1 and GIP are insulinotropic at basal and postprandial glucose levels and contribute nearly equally to the incretin effect of a meal in healthy subjects. Regul Pept 2003;114:115–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Astrup A, Rossner S, Van GL, et al. Effects of liraglutide in the treatment of obesity: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2009;374:1606–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holten MK, Zacho M, Gaster M, et al. Strength training increases insulin-mediated glucose uptake, GLUT4 content, and insulin signaling in skeletal muscle in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2004;53:294–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maayan L, Correll CU. Management of antipsychotic-related weight gain. Expert Rev Neurother 2010;10:1175–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caemmerer J, Correll CU, Maayan L. Acute and maintenance effects of non-harmacologic interventions for antipsychotic associated weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: a meta-analytic comparison of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Res 2012;140:159–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daumit GL, Dickerson FB, Wang NY, et al. A behavioral weight-loss intervention in persons with serious mental illness. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1594–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukundan A, Faulkner G, Cohn T, et al. Antipsychotic switching for people with schizophrenia who have neuroleptic-induced weight or metabolic problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(12):CD006629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermes E, Nasrallah H, Davis V, et al. The association between weight change and symptom reduction in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res 2011;128:166–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, et al. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maayan L, Vakhrusheva J, Correll CU. Effectiveness of medications used to attenuate antipsychotic-related weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010;35:1520–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bagger JI, Christensen M, Knop FK, et al. Therapy for obesity based on gastrointestinal hormones. Rev Diabet Stud 2011;8:339–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lubman DI, King JA, Castle DJ. Treating comorbid substance use disorders in schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2010;22:191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egecioglu E, Steensland P, Fredriksson I, et al. The glucagon-like peptide 1 analogue exendin-4 attenuates alcohol mediated behaviors in rodents. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013;38:1259–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalra S, Kalra B, Sharma A. Change in alcohol consumption following liraglutide initiation: a real-life experience. American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions 2011, Abstract number: 1029–P. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.