Abstract

Neurosarcoidosis is frequently on the differential diagnosis for neurohospitalists. The diagnosis can be challenging due to the wide variety of clinical presentations as well as the limitations of noninvasive diagnostic testing. This article briefly touches on systemic features that may herald suspicion of this disorder and then expands in depth on the neurological clinical presentations. Common patterns of neurological presentations are reviewed and unusual presentations are also included. A discussion of noninvasive testing is undertaken, exploring dilemmas that may be encountered with sensitivity and specificity. Drawing from a broad range of clinical clues and diagnostic data, a systematic approach of pursuing a potential tissue diagnosis is then highlighted. Correctly diagnosing neurosarcoidosis is critical, as treatment with appropriate immunosuppression protocols can then be initiated. Additionally, treatment of refractory disease, the trend toward exploring targeted immunomodulation options, and other therapeutic issues are discussed.

Keywords: autoimmune diseases of the nervous system, general neurology, neurohospitalist

Introduction

Sarcoidosis affects the nervous system in roughly 5% of cases in a variety of ways.1–3 Neurosarcoidosis often masquerades as other disorders, at times creating a lengthy differential and complicated diagnosis.4 Other systemic features of sarcoidosis can shed light on a case but may be nonspecific or subtle, particularly for a neurologist.2,5 Additionally, a disease marker like a serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level may lack sensitivity for diagnosing neurosarcoidosis.6,7 Imaging and spinal fluid studies are helpful noninvasive screens but a more invasive biopsy approach is still the gold standard for diagnosis.8 Thus, a well-versed clinical background in this disorder is paramount for providing expedient and efficient care of these patients. This article will expand on that background with additional attention to clinical inpatient considerations.

Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnostic Considerations

Up to 70% of patients with neurosarcoidosis present to medical attention with their neurological manifestations rather than already having a known systemic diagnosis.5 Nevertheless, an astute clinician can still tease out systemic clues of sarcoidosis in many of these cases. These systemic signs are not infrequent and may include lung disease, constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy, arthralgias, skin findings (ie, erythema nodusum), eye disease (ie, uveitis), spleen involvement, or liver involvement.5 As mentioned, though, it might be difficult to crystallize these findings into a diagnosis without a reference point, otherwise. Thus, the ability to recognize this disorder’s neurological pattern is still critical.

Broad common categories of primary inpatient neurological presentations would include cranial neuropathies, meningeal disease, inflammatory spinal cord disease, subacute peripheral neuropathic weakness, and hypothalamic–pituitary axis clinical findings. In addition to the classic patterns, other less specific and rare presentations will also be reviewed to help clinicians appreciate a wide array of possible manifestations.

Cranial Neuropathies

A facial palsy is the most common clinical finding of neurosarcoidosis, occurring in upward of 50% of patients.2 In isolation this would be more of an outpatient consideration; but 30% of patients with neurosarcoidosis have more than one neurological manifestation on presentation and, specifically, 63% of patients with facial palsy have an additional neurological manifestation.2 Thus, facial palsy (particularly if bilateral) might provide a very relevant clue to aid in the diagnosis of a hospitalized patient; bilateral involvement, whether sequential or simultaneous, is seen in 25% to 50% of patients with facial palsy associated with sarcoidosis.2,5,9 Bilateral facial palsy in general can be an indicator of a secondary etiology other than idiopathic Bell's palsy, including structural, infectious, and inflammatory causes.10 Lyme disease is an infectious etiology to be considered.11 Seroconversion of HIV may be another infectious etiology associated with bilateral facial palsy, particularly in the context of aseptic meningitis.12 Of patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), 35% have bilateral facial weakness as part of their initial presenting symptoms and that number increases to 60% if one includes the full disease course.13 This would typically occur in the context of other features of GBS, but variant presentations of GBS with more restricted bilateral facial diplegia have been less commonly reported.14–17 Additionally, as noted subsequently, neurosarcoidosis can present with a GBS phenotype, so other diagnostic clues are important in differentiating these two diagnoses. Finally, recurrent Bell's palsy also brings another uncommon etiology into the differential, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome but associated facial swelling or tongue plication might be clues to this rare syndrome.18

Optic neuritis is another frequent cranial nerve complication, which needs to be differentiated from idiopathic optic neuritis, multiple sclerosis, and other infectious or inflammatory disorders. Optic neuritis is frequent enough that it is the most common clinical cranial neuropathy in some referral bases.6,19 Imaging suggests a high prevalence of subclinical involvement of the optic nerve (including the optic chiasm).20 Bilateral involvement of this cranial nerve also heralds a stronger suspicion for sarcoidosis. In one series of patients with sarcoidosis, bilateral optic nerve involvement was noted in 13 of the 19 patients who had optic nerve disease.19 Bilateral optic neuritis should also trigger other differential considerations, such as neuromyelitis optica. Cranial nerve VIII is the third most commonly affected cranial nerve, and cranial nerves V, VI, IX, and X are involved in sarcoidosis less frequently.1,2,6,21–24 Both cranial nerve I and/or primary sinonasal involvement of the granulomatous disease have also been encountered.25,26

Meningeal Disease

A more diffuse meningeal infiltration from sarcoidosis can cause a basilar polycranial neuropathy, which needs to be differentiated from other similar meningeal infiltrative processes, such as tuberculosis, fungal meningitis, carcinomatous meningitis, Wegener granulomatosis, idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningitis, or lymphomatous meningitis.27–29 Polycranial neuritis is seen in up to 40% of patients with neurosarcoidosis.5 Meningeal irritation can cause aseptic meningitis, and chronic or recurrent meningitis presentations have been well described.1,2,30 Meningeal infiltration of the arachnoid granulations or cerebral aqueduct may result in the serious and sometimes emergent consequence of hydrocephalus.31,32 Meningeal infiltration of the lumbosacral nerve roots can present as a cauda equina syndrome.33

Inflammatory Spinal Cord Disease

Involvement of the spine may result from leptomeningeal infiltration and/or parenchymal myelitis with cases of longitudinally extensive myelitis (LETM) reported.34,35 Recent literature indicates that myelitis spans an average of 3.9 segments in patients with neurosarcoidosis (typically greater than 3), and this extended segment disease may help provide a distinguishing feature from multiple sclerosis inflammatory lesions of the spinal cord.36 An LETM needs to be primarily differentiated in the inpatient setting from neuromyelitis optica, connective tissue disorders such as Sjogren's disease or Lupus, infectious etiologies, and vascular disorders such as dural arteriovenous fistula.

Peripheral Neuropathy

Acute neuropathic presentations may be encountered in the hospital. Asymmetric polyradiculoneuropathy or a mononeuritis multiplex picture may be differentiating clues of sarcoidosis (Tables 1 and 2).37 Also, of relevance, one may encounter a GBS clinical phenotype secondary to sarcoidosis. Electrophysiological findings may mirror GBS, but in addition to an elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein, one also sees an unexpectedly high pleocytosis.38,39 Sarcoidosis, HIV, and Lyme disease would also be diagnostic considerations with this scenario. A subacute axonal polyneuropathy and small fiber neuropathy are also well known associations with sarcoidosis.40,41 Myopathic involvement in sarcoidosis may occur but is typically asymptomatic.42–46

Table 1.

Common Systemic Clues of Sarcoidosis.

| • Lung disease |

| • Ocular disease (uveitis) |

| • Skin manifestations—ie, erythema nodosum |

| • Lymphadenopathy |

| • Arthralgias and constitutional symptoms |

Table 2.

Examples of Common Inpatient Neurological Presentations.

| Isolated cranial neuropathy (bilateral involvement increases suspicion) |

| Diffuse meningeal or leptomeningeal-based disease |

| • Cranial polyneuropathies |

| • Aseptic or chronic meningitis |

| • Hydrocephalus (ie, infiltration of arachnoid granulations or cerebral aqueduct) |

| • Subacute polyradiculopathy (including cauda equina) |

| Acute to subacute polyneuropathy |

| • Asymmetric polyradiculoneuropathy |

| • Mononeuritis multiplex |

| • Acute Guillain-Barré syndrome phenotype |

| • Subacute length-dependent axonal polyneuropathy |

| • Small-fiber neuropathy |

| Spinal cord disease |

| • Leptomeningeal disease |

| • Longitudinally extensive myelitis |

| Hypothalamic–pituitary axis dysfunction |

Hypothalamic–Pituitary Axis

Hypothalamic–pituitary axis dysfunction can be a clinical expression of neurosarcoidosis. Diabetes insipidus may provide a clinical clue to neurosarcoidosis, and a vast array of other hypothalamic–pituitary axis symptomatology and hormonal irregularities has also been described.47–49 Hypothalamic–pituitary axis symptomatology is radiographically silent in half of all cases.20

Additional Clinical Correlates

Other nonspecific neurological considerations can be associated with neurosarcoidosis. Parenchymal brain involvement can result in seizures,6,19 and less commonly, central nervous system cranial mass lesions can cause focal deficits.1,2 A hospitalized patient with neurosarcoidosis could also present with encephalopathy or even psychosis.50–55

Finally, one must remember that sarcoidosis can present in unusual ways. A neurologist may be involved in cases of orbital masses or inflammation that eventually have sarcoidosis identified as their etiology.56 Osseous sarcoidosis seen on imaging can falsely mimic bony metastases or multiple myeloma.57–59 Neurosarcoidosis may even present in bizarre patterns, such as a description of it mimicking testicular cancer with metastases to the brain.60

An awareness of this disorder is crucial to picking up the relevant clinical findings for diagnosis. Taken together, the neurological and systemic clues provide a framework for suspecting neurosarcoidosis. This clinical foundation is then built upon with noninvasive testing to see whether a biopsy is warranted for disease confirmation.

Diagnostic Dilemmas

There are still significant limitations of approaching diagnostic confirmation of neurosarcoidosis. Noninvasive testing may lack sensitivity and specificity and should be utilized in the context of clinical judgment of whether to pursue more confirmatory invasive testing with a biopsy.

In the setting of neurosarcoidosis, a serum ACE level is only elevated in about a quarter of patients, potentially due to less prominent systemic involvement in these cases, making this a rather low yield test.6,8 Although one series noted a high sensitivity,19 generally, a CSF ACE level has been noted to be rather insensitive (several reports with a range of 24%-55%).7,8,61,62 Although an elevated CSF ACE level has high specificity overall,7,61,62 infectious or carcinomatous processes of the CNS may also result in high CSF ACE levels, which is of particular importance, as these entities can mimic neurosarcoidosis clinically and radiologically.63 Ordering a chest x-ray in patients with suspicion for neurosarcoidosis is a noninvasive screening tool that has value with actually a better yield than a serum ACE level.6,8,19 Chest computed tomography adds a mildly better degree of additional screening value compared to a chest x-ray.6,19 Gallium scanning, evaluating uptake patterns in the lung and parotid regions, has a relatively similar to mildly better screening sensitivity compared to conventional chest imaging in patients with neurosarcoidosis.6,8 An emerging imaging method for aiding in the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis is whole-body fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scanning. There is a suggestion of efficacy of this modality for uncovering otherwise unknown systemic disease or even visualizing neurological involvement not seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).64,65

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain or spinal cord and a lumbar puncture are the most commonly employed neurodiagnostic studies in the evaluation of patients with neurosarcoidosis. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain may nonspecifically show white matter changes or hydrocephalus,6,8 but contrast is necessary to demonstrate some of the more classic findings. Contrast enhancement of the meninges, cranial nerves, or hypothalamic–pituitary axis is commonly seen.8,20 Spinal cord imaging may demonstrate enhancement of the meninges or nerve roots.19,20,36,66 It might also demonstrate LETM or cord swelling.19,36,66 Lumbar puncture commonly demonstrates elevated spinal fluid protein and a mild to moderate pleocytosis is seen in the majority of the patients (5-220 in one series; lymphocytic predominance); taken together 81% of patients have an elevation of at least one of the two.8 Low CSF glucose might also occur, and in rare cases this may even be profound.67,68 Oligoclonal bands can be present and might provide diagnostic confusion with multiple sclerosis depending on the clinical presentation. An elevated CSF protein typically accompanies oligoclonal bands in patients with neurosarcoidosis, helping to differentiate the two disease states.6 A main function of the lumbar puncture is to also exclude central nervous system infection or malignancy. As such, common additions to the CSF evaluation include cultures (including fungal cultures and acid-fast testing), cryptococcal antigen, venereal disease research laboratory, and cytology.

Weighing the patient’s clinical presentation along with the above-mentioned noninvasive diagnostic information will help one decide whether to consider a more invasive biopsy. If the patient has demonstration of systemic disease, a pertinent biopsy of a lymph node, the skin, or a transbronchial lung biopsy may be undertaken.6,19,63 This would be a favored strategy to establish a diagnosis of probable neurosarcoidosis less invasively, allowing subsequent initiation of appropriate treatment accordingly in patients without fulminant neurological disease.8 In cases without obvious systemic disease, a blind systemic biopsy may still be pursued to document a probable diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. A muscle biopsy, conjunctival biopsy, and bone marrow biopsy are all reasonable alternatives, with typically a 30% to 50% yield for identifying pertinent pathology, such as noncaseating granulomas.44,63,69 In patients without a systemic biopsy diagnosis or in patients needing a more definitive diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis, one may pursue a clinically relevant nervous system lesion to biopsy as a more invasive option, if necessary. This would generally involve a biopsy of an enhancing area of the meninges, a significant central nervous system parenchymal lesion that is readily accessible to the surgeon with an acceptable risk profile, or a peripheral nerve if there is peripheral nervous system involvement. If there is myopathy, a muscle biopsy could be obtained, but again a muscle site is employed much more commonly in evaluating subclinical, asymptomatic disease with a blind biopsy (Figures 1 –5).44

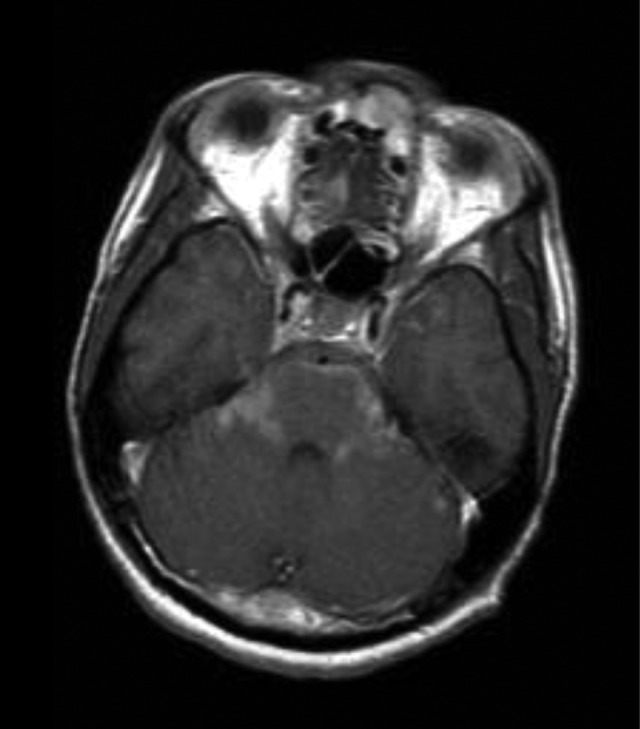

Figure 1.

Basilar infiltration on contrast-enhanced scan.

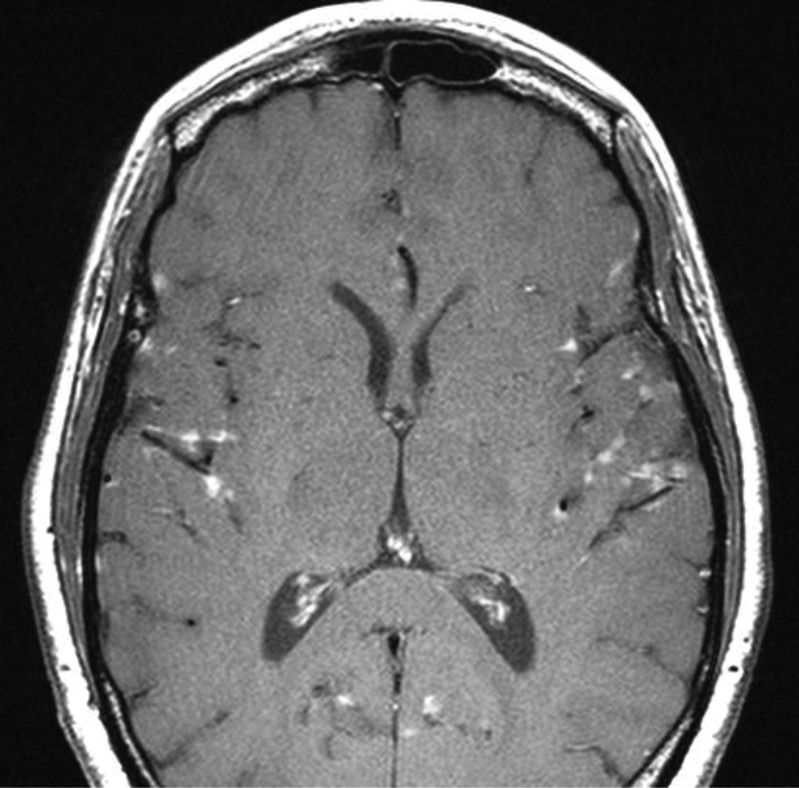

Figure 2.

Leptomeningeal enhancement.

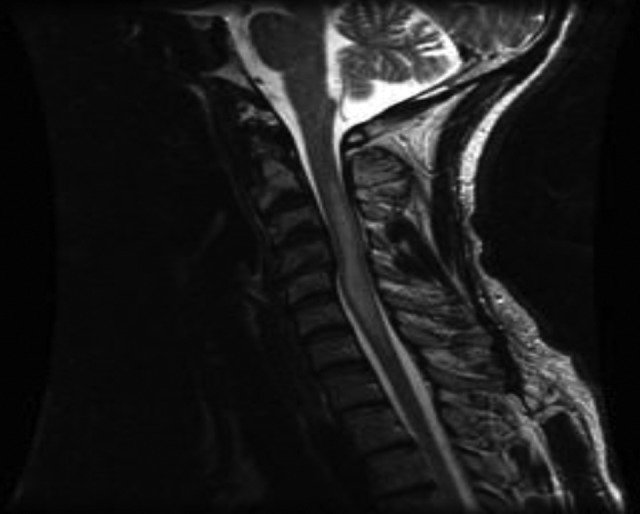

Figure 3.

Long segment transverse myelitis.

Figure 4.

Nodular involvement of the cauda equina with vertebral involvement.

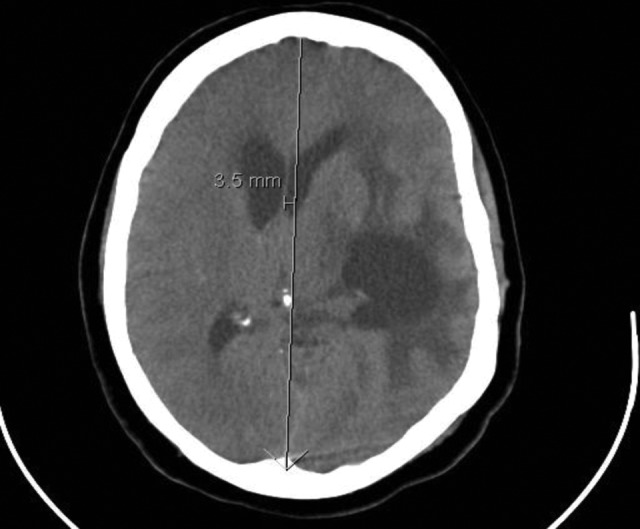

Figure 5.

Acute hydrocephalus with trapped left temporal horn, transependymal fluid, and midline shift as a presentation of neurosarcoidosis.

Treatment

Corticosteroids are the first-line treatment for patients with neurosarcoidosis.70 The clinical decision tree beyond that for the hospitalized patient involves whether to start a pulse of intravenous (IV) steroids before converting to oral corticosteroids, whether a secondary agent is needed, and what to recommend regarding the duration of therapy.

Neurosarcoidosis is to be initially treated with 1 mg/kg of oral prednisone daily generally for 6 to 8 weeks with a slow taper as tolerated (this may be preceded by a pulse of IV solumedrol at the initiation of treatment for severe cases).71 However, various clinical presentations may alter treatment duration. Bell's palsy can be treated with high doses of steroids for a week with a fast taper over the second week, and a similar, shorter treatment course of corticosteroids can be considered in isolated aseptic meningitis, which also typically runs a more benign course with frequent remissions.72,73 Conversely, central nervous system lesions, hydrocephalus, spinal cord disease, optic neuropathy, and seizures indicate more resistant disease that will likely require protracted courses of treatment.8,72 Long term, it may be difficult to sustain weans lower than 20 to 25 mg daily of prednisone in patients with more aggressive manifestations of neurosarcoidosis.8

In patients who have inadequate benefit or concern for side effects from corticosteroid therapy, have relapses while attempting weaning of steroids, or have indicators of poor prognosis with a high likelihood of relapse, one may consider cytotoxic therapy. Methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and cyclophosphamide have all been utilized.74–77 The onset of action may be slow, and then even if it has reached full efficacy, further treatment is still recommended for at least another 3 to 6 months of clinical stability before starting any weaning attempts.71

Despite the above-mentioned measures, some patients may still remain refractory to treatment. Although radiation therapy has even been used in refractory disease,78–80 there is a growing trend to support a trial of targeted immunomodulation in these patients. In sarcoidosis, there is a T-helper type 1-mediated reaction to an antigen stimulus. Specifically, tumor necrosis factor α has been highly associated with this process in sarcoidosis.81 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, such as infliximab and thalidomide, have shown some promise in treating patients with refractory neurosarcoidosis.82–96

Hydrocephalus secondary to neurosarcoidosis can be an emergent and life-threatening situation in the hospital setting. Close clinical monitoring of these patients is required, and a neurosurgical consultation is recommended to assist in the evaluation and management of hydrocephalus. As noted previously, high-dose steroids, preferably including IV methylprednisolone initially, are started if sarcoidosis is confirmed and a prolonged treatment course is advised.97,98 A patient with asymptomatic or mild, stable hydrocephalus can be managed with long courses of high-dose steroids alone but unstable, life-threatening, or corticosteroid-resistant hydrocephalus requires ventricular shunting.73

In general, peripheral neuropathic processes that are acute to subacute rationalize a search for an inflammatory etiology that may be treatable. In patients diagnosed with neurosarcoidosis, treatment is generally similar to the general algorithm outlined previously. Patients who present with a Guillain-Barré-like clinical and electrophysiological phenotype secondary to sarcoidosis may be difficult to sort out from patients with typical GBS, initially, though. Starting with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or even plasmapheresis in those patients would be reasonable, especially given the concern for a poor response with steroids for typical GBS. Nevertheless, if there is an unexpectedly high pleocytosis in the CSF followed by additional confirmation of sarcoidosis, then following up with further steroid treatment per a neurosarcoidosis protocol would be recommended. Of note, IVIG has also otherwise been used in some peripheral neurosarcoidosis scenarios with apparent benefit, discussed in case reports with improvement in sensory predominant, axonal polyneuropathy, and small-fiber neuropathy.99,100

Summary

Neurosarcoidosis can be an elusive diagnosis and must be on the differential diagnosis in multiple inpatient scenarios. Noninvasive screening may lack sensitivity or specificity and tissue biopsy is still the gold standard for diagnosis. A thorough understanding of the neurologic syndromes associated with this condition is necessary for appropriate patient care. Treatment with corticosteroids can be effective, although cytotoxic therapy is sometimes a required adjunct; targeted immunomodulation is an increasingly promising approach to refractory disease.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Delaney P. Neurologic manifestations in sarcoidosis: review of the literature, with a report of 23 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87(3):336–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stern BJ, Krumholz A, Johns C, Scott P, Nissim J. Sarcoidosis and its neurological manifestations. Arch Neurol. 1985;42(9):909–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10 pt 1):1885–1889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spiegel DR, Morris K, Rayamajhi U. Neurosarcoidosis and the complexity in its differential diagnoses: a review. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9:10–16 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gascón-Bayarri J, Mañá J, Martínez-Yélamos S, Murillo O, Reñé R, Rubio F. Neurosarcoidosis: report of 30 cases and a literature survey. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(6):e125–e132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Joseph FG, Scolding NJ. Neurosarcoidosis: a study of 30 new cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(3):297–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khoury J, Wellik KE, Demaerschalk BM, Wingerchuk DM. Cerebrospinal fluid angiotensin-converting enzyme for diagnosis of central nervous system sarcoidosis. Neurologist. 2009;15(2):108–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis—diagnosis and management. QJM Mon J Assoc Physicians. 1999;92(2):103–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Colover J. Sarcoidosis with involvement of the nervous system. Brain J Neurol. 1948;71(pt 4):451–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Keane JR. Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature. Neurology. 1994;44(7):1198–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jain V, Deshmukh A, Gollomp S. Bilateral facial paralysis: case presentation and discussion of differential diagnosis. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):C7–C10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Serrano P, Hernández N, Arroyo JA, de Llobet JM, Domingo P. Bilateral Bell palsy and acute HIV type 1 infection: report of 2 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(6):e57–e61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ropper AH. The Guillain-Barré syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(17):1130–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Susuki K, Koga M, Hirata K, Isogai E, Yuki N. A Guillain-Barré syndrome variant with prominent facial diplegia. J Neurol. 2009;256(11):1899–1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sethi NK, Torgovnick J, Arsura E, Johnston A, Buescher E. Facial diplegia with hyperreflexia—a mild Guillain-Barre Syndrome variant, to treat or not to treat? J Brachial Plex Peripher Nerve Inj. 2007;2:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Narayanan RP, James N, Ramachandran K, Jaramillo MJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome presenting with bilateral facial nerve paralysis: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1(1):379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Curtis CE, Barnes EV, Dupiche CA. Guillain-Barré syndrome variant: presenting with myalgias and acute facial diplegia. Mil Med. 2008;173(5):507–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elias MK, Mateen FJ, Weiler CR. The Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome: a retrospective study of biopsied cases. J Neurol. 2013;260(1):138–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pawate S, Moses H, Sriram S. Presentations and outcomes of neurosarcoidosis: a study of 54 cases. QJM. 2009;102(7):449–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Christoforidis GA, Spickler EM, Recio MV, Mehta BM. MR of CNS sarcoidosis: correlation of imaging features to clinical symptoms and response to treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(4):655–669 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Colvin IB. Audiovestibular manifestations of sarcoidosis: a review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(1):75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Szmulewicz DJ, Waterston JA. Two patients with audiovestibular sarcoidosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19(1):158–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amin A, Balderacchi JL. Trigeminal neurosarcoidosis: case report and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89(7):320–322 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alon EE, Ekbom DC. Neurosarcoidosis affecting the vagus nerve. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010;119(9):641–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aubart FC, Ouayoun M, Brauner M, et al. Sinonasal involvement in sarcoidosis: a case–control study of 20 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006;85(6):365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Delaney P, Henkin RI, Manz H, Satterly RA, Bauer H. Olfactory sarcoidosis. Report of five cases and review of the literature. Arch Otolaryngol. 1977;103(12):717–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hildebrand J, Aoun M. Chronic meningitis: still a diagnostic challenge. J Neurol. 2003;250(6):653–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vargas DL, Stern BJ. Neurosarcoidosis: diagnosis and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31(4):419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meltzer CC, Fukui MB, Kanal E, Smirniotopoulos JG. MR imaging of the meninges. Part I. Normal anatomic features and nonneoplastic disease. Radiology. 1996;201(2):297–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ginsberg L, Kidd D. Chronic and recurrent meningitis. Pract Neurol. 2008;8(6):348–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Westhout FD, Linskey ME. Obstructive hydrocephalus and progressive psychosis: rare presentations of neurosarcoidosis. Surg Neurol. 2008;69(3):288–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akhondi H, Barochia S, Holmström B, Williams MJ. Hydrocephalus as a presenting manifestation of neurosarcoidosis. South Med J. 2003;96(4):403–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kaiboriboon K, Olsen TJ, Hayat GR. Cauda equina and conus medullaris syndrome in sarcoidosis. Neurologist. 2005;11(3):179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dolhun R, Sriram S. Neurosarcoidosis presenting as longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(4):595–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sierra-Hidalgo F, Moreno-Ramos T, Martínez de Aragón A, Correas-Callero E, Eraña I, de Pablo-Fernández E. Longitudinal myelitis as the presenting symptom of neurosarcoidosis [in Spanish]. Rev Neurol. 2010;51(5):302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sohn M, Culver DA, Judson MA, Scott TF, Tavee J, Nozaki K. Spinal cord neurosarcoidosis [published online January 29, 2013]. Am J Med Sci. 2013. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182808781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Burns TM, Dyck PJ, Aksamit AJ, Dyck PJ. The natural history and long-term outcome of 57 limb sarcoidosis neuropathy cases. J Neurol Sci. 2006;244(1-2):77–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fahoum F, Drory VE, Issakov J, Neufeld MY. Neurosarcoidosis presenting as Guillain-Barré-like syndrome. a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2009;11(1):35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Saifee TA, Reilly MM, Ako E, et al. Sarcoidosis presenting as acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(2):296–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zuniga G, Ropper AH, Frank J. Sarcoid peripheral neuropathy. Neurology. 1991;41(10):1558–1561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tavee J, Culver D. Sarcoidosis and small-fiber neuropathy. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(3):201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Silverstein A, Siltzbach LE. Muscle involvement in sarcoidosis. asymptomatic, myositis, and myopathy. Arch Neurol. 1969;21(3):235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wallace SL, Lattes R, Malia JP, Ragan C. Muscle involvement in Boeck’s sarcoid. Ann Intern Med. 1958;48(3):497–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zisman DA, Shorr AF, Lynch JP III. Sarcoidosis involving the musculoskeletal system. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;23(6):555–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Scola RH, Werneck LC, Prevedello DM, Greboge P, Iwamoto FM. Symptomatic muscle involvement in neurosarcoidosis: a clinicopathological study of 5 cases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2001;59(2-B):347–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kolilekas L, Triantafillidou C, Manali E, Rontogianni D, Chatziioannou S, Papiris S. The many faces of sarcoidosis: asymptomatic muscle mass mimicking giant-cell tumor. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29(11):1389–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chapelon C, Ziza JM, Piette JC, et al. Neurosarcoidosis: signs, course and treatment in 35 confirmed cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1990;69(5):261–276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Porter N, Beynon HL, Randeva HS. Endocrine and reproductive manifestations of sarcoidosis. QJM. 2003;96(8):553–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Langrand C, Bihan H, Raverot G, et al. Hypothalamo-pituitary sarcoidosis: a multicenter study of 24 patients. QJM. 2012;105(10):981–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ho SU, Berenberg RA, Kim KS, Dal Canto MC. Sarcoid encephalopathy with diffuse inflammation and focal hydrocephalus shown by sequential CT. Neurology. 1979;29(8):1161–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rivera Cívico JM, Marín León I, Dastis Bendala C, García-Bragado Dalmau F. Hypercalcemic encephalopathy. Initial manifestation of sarcoidosis [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 1989;93(7):279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rudkin AK, Wilcox RA, Slee M, Kupa A, Thyagarajan D. Relapsing encephalopathy with headache: an unusual presentation of isolated intracranial neurosarcoidosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(7):770–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Celebi A, Deveci S, Gursoy AE, Kolukisa M. A case of isolated neurosarcoidosis associated with psychosis. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2013;18(1):70–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bona JR, Fackler SM, Fendley MJ, Nemeroff CB. Neurosarcoidosis as a cause of refractory psychosis: a complicated case report. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(8):1106–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. O'Brien GM, Baughman RP, Broderick JP, Arnold L, Lower EE. Paranoid psychosis due to neurosarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis. 1994;11(1):34–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gutman J, Shinder R. Orbital and adnexal involvement in sarcoidosis: analysis of clinical features and systemic disease in 30 cases. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;152(5):883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Frattalone S, O'Sullivan S, Edison J. Osseous sarcoidosis presenting as lytic lesions of the skull and cervical spine. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(3):649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Suri V, Singh A, Das R, et al. Osseous sarcoid with lytic lesions in skull [published online April 23, 2013.]. Rheumatol Int. 2013. doi:10.1007/s00296-013-2752-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Moore SL, Kransdorf MJ, Schweitzer ME, Murphey MD, Babb JS. Can sarcoidosis and metastatic bone lesions be reliably differentiated on routine MRI? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(6):1387–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gupta R, Senadhi V. A diagnostic dilemma: metastatic testicular cancer and systemic sarcoidosis—a review of the literature. Case Reports Oncol. 2011;4(1):118–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Oksanen V, Fyhrquist F, Somer H, Grönhagen-Riska C. Angiotensin converting enzyme in cerebrospinal fluid: a new assay. Neurology. 1985;35(8):1220–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dale JC, O'Brien JF. Determination of angiotensin-converting enzyme levels in cerebrospinal fluid is not a useful test for the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. Mayo Clin Proc Mayo Clin. 1999;74(5):535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Aksamit AJ, Norona F. Neurosarcoidosis without systemic sarcoid. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:471 [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bolat S, Berding G, Dengler R, Stangel M, Trebst C. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is useful in the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287(1-2):257–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Huang JF, Aksamit AJ, Staff NP. MRI and PET imaging discordance in neurosarcoidosis. Neurology. 2012;79(10):1070–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Junger SS, Stern BJ, Levine SR, Sipos E, Marti-Masso JF. Intramedullary spinal sarcoidosis: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging characteristics. Neurology. 1993;43(2):333–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gaines JD, Eckman PB, Remington JS. Low CSF glucose level in sarcoidosis involving the central nervous system. Arch Intern Med. 1970;125(2):333–336 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sarva H, Chapman R, Omoregie E, Abrams C. The challenge of profound hypoglycorrhachia: two cases of sarcoidosis and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(12):1631–1639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chung YM, Lin YC, Huang DF, Hwang DK, Ho DM. Conjunctival biopsy in sarcoidosis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69(10):472–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Selroos O. Treatment of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis. 1994;11(1):80–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hoitsma E, Faber CG, Drent M, Sharma OP. Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(7):397–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Luke RA, Stern BJ, Krumholz A, Johns CJ. Neurosarcoidosis: the long-term clinical course. Neurology. 1987;37(3):461–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Stern BJ. Neurological complications of sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17(3):311–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Agbogu BN, Stern BJ, Sewell C, Yang G. Therapeutic considerations in patients with refractory neurosarcoidosis. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(9):875–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Androdias G, Maillet D, Marignier R, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil may be effective in CNS sarcoidosis but not in sarcoid myopathy. Neurology. 2011;76(13):1168–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Doty JD, Mazur JE, Judson MA. Treatment of corticosteroid-resistant neurosarcoidosis with a short-course cyclophosphamide regimen. Chest. 2003;124(5):2023–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Stern BJ, Schonfeld SA, Sewell C, Krumholz A, Scott P, Belendiuk G. The treatment of neurosarcoidosis with cyclosporine. Arch Neurol. 1992;49(10):1065–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bruns F, Pruemer B, Haverkamp U, Fischedick AR. Neurosarcoidosis: an unusual indication for radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 2004;77(921):777–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Menninger MD, Amdur RJ, Marcus RB., Jr Role of radiotherapy in the treatment of neurosarcoidosis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26(4):e115–e118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Grizzanti JN, Knapp AB, Schecter AJ, Williams MH., Jr Treatment of sarcoid meningitis with radiotherapy. Am J Med. 1982;73(4):605–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Moller DR. Treatment of sarcoidosis—from a basic science point of view. J Intern Med. 2003;253(1):31–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB, Bognar B. Refractory neurosarcoidosis: a dramatic response to infliximab. Am J Med. 2004;117(4):277–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chintamaneni S, Patel AM, Pegram SB, Patel H, Roppelt H. Dramatic response to infliximab in refractory neurosarcoidosis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2010;13(3):207–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kobylecki C, Shaunak S. Refractory neurosarcoidosis responsive to infliximab. Pract Neurol. 2007;7(2):112–115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Morcos Z. Refractory neurosarcoidosis responding to infliximab. Neurology. 2003;60(7):1220-1221; author reply 1220–1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. O'Reilly MW, Sexton DJ, Dennedy MC, et al. Radiological remission and recovery of thirst appreciation after infliximab therapy in adipsic diabetes insipidus secondary to neurosarcoidosis [published online February 14, 2013]. QJM. 2013. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hct023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Pereira J, Anderson NE, McAuley D, Bergin P, Kilfoyle D, Fink J. Medically refractory neurosarcoidosis treated with infliximab. Intern Med J. 2011;41(4):354–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pettersen JA, Zochodne DW, Bell RB, Martin L, Hill MD. Refractory neurosarcoidosis responding to infliximab. Neurology. 2002;59(10):1660–1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Salama B, Gicquel JJ, Lenoble P, Dighiero PL. Optic neuropathy in refractory neurosarcoidosis treated with TNF-alpha antagonist. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006;41(6):766–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Santos E, Shaunak S, Renowden S, Scolding NJ. Treatment of refractory neurosarcoidosis with Infliximab. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(3):241–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Sodhi M, Pearson K, White ES, Culver DA. Infliximab therapy rescues cyclophosphamide failure in severe central nervous system sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2009;103(2):268–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Sollberger M, Fluri F, Baumann T, et al. Successful treatment of steroid-refractory neurosarcoidosis with infliximab. J Neurol. 2004;251(6):760–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Moravan M, Segal BM. Treatment of CNS sarcoidosis with infliximab and mycophenolate mofetil. Neurology. 2009;72(4):337–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hammond ER, Kaplin AI, Kerr DA. Thalidomide for acute treatment of neurosarcoidosis. Spinal Cord. 2007;45(12):802–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Hoyle JC, Newton HB, Katz S. Prognosis of refractory neurosarcoidosis altered by thalidomide: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Nguyen YT, Dupuy A, Cordoliani F, et al. Treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis with thalidomide. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(2):235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Foley KT, Howell JD, Junck L. Progression of hydrocephalus during corticosteroid therapy for neurosarcoidosis. Postgrad Med J. 1989;65(765):481–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Benzagmout M, Boujraf S, Góngora Rivera F, Bresson D, Van Effenterre R. Neurosarcoidosis which manifested as acute hydrocephalus: diagnosis and treatment. Intern Med. 2007;46(18):1601–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Parambil JG, Tavee JO, Zhou L, Pearson KS, Culver DA. Efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin for small fiber neuropathy associated with sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2011;105(1):101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Heaney D, Geddes JF, Nagendren K, Swash M. Sarcoid polyneuropathy responsive to intravenous immunoglobulin. Muscle Nerve. 2004;29(3):447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]