Abstract

Background

During the colonial period, the indigenous saraguros maintained their traditions, knowledge, and practices to restore and preserve the health of their members. Unfortunately, many of their practices and medicinal resources have not been documented. In this study, we sought to document the traditional healers’ (yachakkuna saraguros) knowledge about medicinal and psychoactive plants used in the mesas and in magical-religious rituals. The study was conducted under a technical and scientific cooperation agreement between the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL), the Dirección Provincial de Salud de Loja (DPSL), and the Saraguro Healers Council (Consejo de Sanadores de Saraguro).

Methods

For the present study, the DPSL and Saraguro Healers Council selected the 10 yachakkuna most recognized for their knowledge and their use of sacred and psychoactive species. Ten interviews with the selected yachakkuna were conducted between 2010 and 2011 to ascertain how the Saraguro traditional healing system is structured and to obtain a record of the sacred and medicinal plant species used to treat supernatural diseases and for psychoactive purposes.

Results

The present study describes the traditional health system in the Saraguro indigenous community located in southern Ecuador. It also describes the main empirical methods used to diagnose diseases: direct physical examination of the patient, observation of the patient’s urine, documentation of the patient’s pulse, limpia, palpation and visionary methods, including supernatural diseases (susto, vaho de agua, mal aire, mal hecho, shuka) and reports of the use of sacred and medicinal psychoactive plants, such as the San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis pachanoi), wandug (Brugmansia spp.), and tobacco (Nicotiana spp.). This study also describes the rituals (limpia, soplada) employed by the Saraguro yachakkuna to treat supernatural diseases. Finally, we report on the main plants used during limpia in the Saraguro community.

Conclusion

The current traditional health system in the Saraguro community is the cultural expression of the Saraguros’ presence as an Andean group in southern Ecuador: it represents their character as indigenous group, their ability to survive as a community despite strong external pressure, and the desire to maintain their ancient healing heritage.

Keywords: San Pedro cactus, Medicinal plants, Saraguro, Psychoactive plants, Yachakkuna, Healing rituals

Background

The use of medicinal plants by several indigenous communities in South America, and particularly the use of hallucinogenic plants with therapeutic purposes, is linked to the shamanism that the ancient hunters brought on their journey from Northeast Asia to the modern-day American continent [1,2]. Ancient civilizations that migrated from Asia and settled in America believed that diseases are closely linked to spirits and esoteric rituals. Thus, shamanic practices were closely related to the use of hallucinogenic species that allowed the shamans to reach several states of consciousness or visionary experiences, in a way similar to that of current shamans from different indigenous communities in South America [3,4]. In the Andean region, these healers are known as yachak or yachakkuna[5].

According to Cabieses [6], three types of consumption have been identified and vary according to the location in the South American Andes, the type of plants consumed, and the mechanism of action exerted by psychoactive chemicals: (i) mescalinismo (the consumption of cactus containing mescaline, such as Echinopsis pachanoi) in Andean valleys and desert areas of the coast; (ii) cocainism (the use of Erythroxylum coca) in the valleys and plateaus of the Andes; and (iii) harminism (the consumption of plants containing harmine, such as the ayahuasca beverage) in the Amazon.

In the Ecuadorian Andes, the use of plants as therapeutic agents is an important feature of traditional medicine and is still practiced in many indigenous communities. A noteworthy example is the Saraguro ethnic group, which belongs to the Kichwa community of Ecuador. The Saraguro group is located in the southern region of the country (Loja and Zamora-Chinchipe provinces), as shown in Figure 1. This region is known as the area with the greatest biodiversity on the planet; it contains approximately 4,000 species of vascular plants [7,8] and is located in the Podocarpus National Park. In the province of Loja, the Saraguro community lives in the canton that bears its name.

Figure 1.

Southern region of Ecuador.

The Saraguro community has a population of approximately 60,000 inhabitants. They are considered one of the most organized ethnic groups in Ecuador, and they preserve their ancestral knowledge and technology, culture, medicine, language, and customs [9-11]. Currently, the majority of Saraguro community members speak runashimi (the Kichwa language) and Spanish, whereas the Saraguros who inhabit remote areas, such as Tambopamba, Gera, or Oñacapac, speak only Kichwa.

The origin of the Saraguros as an indigenous community was not determined until recently. Some theories claim that the Saraguros are mitimaes, part of a conquered population forced by the Incas to settle in a distant area. For this reason, they were mobilized by the Incas as part of a strategy to ensure social peace within the Inca Empire. According to Rowe [12], a small group of paltas (native inhabitants of Loja) was transferred to Bolivia and, at the same time, a number of the inhabitants of the Bolivian Altiplano were transferred and established in the current Saraguro’s locations. In Kichwa language, Saraguro means “land of corn”. Among Saraguro communities, family is the basis of their cultural identity: their beliefs, traditions, and customs as well as the use of medicinal plants and traditional knowledge are transmitted orally among family members [13].

Over the years, the Saraguro population has used a broad variety of medicinal plants [10,14]. Previous studies of the Saraguro community describe the existence of hampiyachakkuna (wise men or women) who have knowledge of plants’ healing properties [9,15,16]. These people use their wisdom to heal diseases in accordance with the medical traditions of other Andean communities. Yachakkuna are responsible for diagnosing, treating, and healing physical diseases and other disorders that have a supernatural character.

Although previous studies have considered the use of hallucinogenic and sacred species plants by Ecuadorian yachakkuna[17,18], there are no reported studies on traditional Saraguro medicine. Considering the lack of ethnobotanical information on the Saraguros medical traditions, the current research describes the empirical healing methods that are used by this community. The aim of the present study is to provide data on plant species and other natural resources that are used during healing rituals and have magical and religious significance. This research is part of a strategy that seeks to rescue and validate ethnic consciousness and to promote the sustainable use of Saraguro medicinal and biological resources.

Methods

The study was conducted under a technical and scientific cooperation agreement between the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL), the Dirección Provincial de Salud de Loja (DPSL), and the Saraguro Healers Council (Consejo de Sanadores de Saraguro) to recover and recognize the traditional knowledge of herbal medicinal resources used by the Saraguro community. For the present study, the DPSL and Saraguro Healers Council selected the 10 yachakkuna most recognized for their knowledge and use of sacred and psychoactive species. In recent years, 65 indigenous Saraguro yachakkuna have been registered by the health department because they have been working for several years in the region of Saraguro; such support has been crucial for the development of this study. The interviewed healers were two women and eight men aged 65 to 80 years old.

The selected yachakkuna worked daily in agriculture, in animal care, and at home. Three of them had no education of any kind, two of them attended primary school, four were enrolled in secondary school but did not complete it, and one attended university and worked as a teacher in a bilingual school in the Saraguro city.

These yachakkuna have undergone a training process for most of their lives. Nine of them obtained knowledge of traditional medicine from their grandfather, father, mother, or another close relative. One of them was trained by an old yachak from his community without any interference from his family. They all have participated in at least one healing experience conducted by a yachak from another Andean indigenous community in Ecuador, such as Cañar, Chimborazo, Imbabura, or Pichincha. Two of the yachakkuna gained experience by working with Shuar shamans from the Amazonian region of Ecuador and shamans from southern Ecuador and northern Perú. Another fact that validates their experience is their participation as leaders in the raymis rituals, celebrations, and other ceremonies in Saraguro and other communities. One of the yachak has been accredited by the DPSL and sent to attend ceremonies and exhibitions as a representative outside of Ecuador.

Ten interviews with the selected yachakkuna were conducted between 2010 and 2011 to describe how the Saraguro traditional healing system is structured and to obtain a record of the sacred and medicinal plant species used to treat supernatural diseases and for psychoactive purposes. Information about extract preparation, the plant part used, and the manner of application or administration of plant species was obtained from these surveys. With the permission of each yachakkuna, photographs of each plant species were taken to create a digital database of these plants. A photographic record of the ceremonies and healing rituals was also created.

The obtained data were gathered in tables containing ethnobotanical information regarding the plants’ common name in Kichwa, scientific name, medicinal use, preparation, and administration. The interviewed yachakkuna were brought together to establish an accurate definition of the concepts of health and disease; during these sessions, it was decided that the Kichwa name should be used for some supernatural diseases.

The plants were collected in three different locations where the yachakkuna typically collect them (Table 1). The collected samples were identified in the Universidad Nacional de Loja (UNL) Herbarium with the collaboration of the Bolivar Merino curator of the herbarium. Reference samples were deposited in the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL) Herbarium with their own identification number. The systematics and nomenclature of the species reported in the study were based on the Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of Ecuador (Jørgensen & Leon-Yanez, 1999).

Table 1.

Coordinates of the plant collecting locations in the Saraguro regions

| Location | Coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Achupallas |

17694877E |

9594739 N |

2,890 mamsl |

|

Sunin |

17694877E |

9594739 N |

3,128 mamsl |

| Fierro Urku | 17686161E | 9589043 N | 3,621 mamsl |

This work was realized with the support of the Secretaria Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología del Ecuador (SENESCYT) and the permission of the Ministry of the Environment of Ecuador.

Results and discussion

Traditional healthcare system in Saraguro

The healthcare system in Saraguro is based on the knowledge of the yachakkuna, who can be classified into four categories depending on their expertise: (i) the wachakhampiyachak (midwife), who uses plants and natural remedies to cure diseases during prenatal care, birth, postpartum and in the early years of a baby’s life; (ii) the yurakhampiyachak, who uses garden or wild plants to cure diseases that have organic symptoms, such as headache or fever; (iii) the kakuyhampiyachak (a person who treats bone and joint disorders), who prepares bandages and lotions with plant extracts and animal fats to cure muscle problems (sprains) and broken bones; (iv) the rikuyhampiyachak (authentic shaman), who uses hallucinogenic and psychoactive plants to cure supernatural diseases during sessions that are known as mesas or mesadas (rituals with religious and magical significance) [15,19,20].

In the Saraguro community, the hampiyachakkuna are accredited as such by their own community based on their experience and success in treating and curing diseases. During the 1970s, small health centers and subcenters of the government healthcare system were created in Saraguro; therefore, today there are two types of healthcare systems: the traditional system typical of Saraguro community, which is composed of yachak; and the conventional health system, which consists of physicians (specialist or general physicians) and nurses.

Currently, the traditional healing methods used in Saraguro community consist of a mixture of indigenous, Spanish, and modern practices. Thus, if the yachak establishes that the disease cannot be treated using the empirical method, they suggest using modern medical methods.

A previous study showed that in 2009, only 30 cases out of 47 were treated at health subcenters in Saraguro, meaning that pregnant indigenous women prefer to trust their health and their children’s health to the wachakhampiyachak. This is a clear example of the accreditation of the hampiyachakkuna by their own community.

At present, the Loja Department of Provincial Health’s Department of Indigenous Health has 65 yachakkuna registered for a community of 60,000 members, which can be considered a representative number given the total number of the community members.

According to José Cartuche Quizhpe, a Saraguro community leader, each yachak must demonstrate the effectiveness of his cures before being accepted as a healer by the community because the prestige and fame of the yachakkuna are based on the effectiveness of their cures. The effectiveness of healing is a filter that prevents a charlatan from claiming to be a yachak.

World view of disease according to Saraguro community

For all the yachakkuna consulted, diseases are the result of an imbalance between the individual, his or her immediate environment, and the spiritual world. The yachakkuna from this community define the body’s ability to react to diseases as jinchi (vital balance); a strong jinchi enables the body to resist diseases, whereas a weak jinchi makes the body more susceptible to diseases. This view is in agreement with the Andean world view, which states that to enjoy health and wellness, a person must first be in harmony with himself or herself, a state that in Kichwa is known as allicai; second, he or she must live in harmony with the others, a condition that is known as allikawsay[21].

Generally, disease can be caused by spiritual factors (such as encanto, susto, mal aire, malos espiritus) acting autonomously or inflicted by other person. Other factors that cause diseases are transgressions of moral or social norms and organic disorders. Table 2 presents the origins of diseases according to the Andean world view.

Table 2.

Causes of diseases according to the Andean worldview of health and disease

| Disorder | Cause | Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Organic disorder |

Poor diet, poor intake of food and beverage, alimentary excess |

Alteration of the digestive, respiratory, circulatory, nervous or reproductive systems |

| Psychosocial disorder |

Transgression of moral or social norms |

Anger, rage, envy, suffering, grief |

| Supernatural disorder | Negative energy of a person or place | Shuka, mal de ojo, susto, encanto, supernatural diseases |

Among the Saraguro members and other different indigenous groups in the Andes, there are diseases that are defined by a specific term [22]; for example, la peste (plague) is used to describe various infectious diseases, such as the flu.

Main diagnostic methods used by the Saraguro community

In Andean medicine, the empirical methods used to describe diseases are simple and straightforward; the necessary data about disease being treated are obtained from the personal dialogue between the patient and yachak. Observation, sight, hearing, and touch are important tools used to investigate the patient’s body diagnose the disease.

In indigenous medicine, there are situations in which the diagnosis is followed by treatment in the same manner used in occidental medicine. Nevertheless, in some cases, the diagnosis and treatment take place simultaneously: for example, while cleansing the patient with egg, the yachak finds out which part of the body is sick and, at the same time, he or she heals the patient by eliminating negative energy.

Table 3 presents the main ancestral diagnostic practices used in traditional medicine in Saraguro.

Table 3.

Diagnostic methods used in empirical medicine in the Saraguro community

| Type of diagnosis | Description of the method |

|---|---|

| Direct physical examination of the patient |

The yachak observes the patient’s face, eyes, or tongue, for example, when diagnosing susto or espanto. |

| Observation of the urine |

The yachak observes the patient’s urine, for example, when diagnosing an intestinal inflammation. |

| Patient’s pulse |

The yachak observes the patient’s pulse; for example, the healer can determine if the patient is worried or has a nervous condition that must be treated. |

|

Limpia (cleaning) with an egg |

The yachak passes a chicken egg over the area to be treated. The egg is then deposited in a glass with water. The healer observes the egg and then he/she establishes the diagnosis, for example, when diagnosing vaho de aire. |

| Palpation |

This method is used to determine whether there is any broken bone or muscle contracture. It is also used by the wachakhampiyachak (midwife) to determine the position of the fetus during pregnancy. |

| Visionary methods | This method is used by visionary yachak. Under the effect of hallucinogenic species and/or psychoactive preparations, the yachak reaches a state of ecstasy. In this state, the healer can determine the problem that affects a person and how to treat it, for example, when diagnosing shuka or envy. |

Classification of supernatural diseases

According to the Saraguro world view, supernatural diseases are considered more important than other types of diseases, thus indicating a strong magical and religious concept of health and disease that is still maintained by Saraguro community and has been described in previous studies [19,20,23,24]. Table 4 presents the definition of each supernatural disease according to the Saraguro worldview.

Table 4.

Definitions of supernatural diseases in the Saraguro community

| Disease | Definition | Symptomatology |

|---|---|---|

|

Susto |

A disease that is produced by unpleasant experiences, accidents, violent episodes, or moments of distress that produce an emotional impact on the patient. |

Nervousness, lack of appetite, sleep loss. |

|

Vaho de agua |

This disease occurs when the person is exposed to water mist, for example, when crossing a bridge. People who have been beaten or injured or women who have recently given birth are more susceptible to this disease. |

Severe pain in the extremities, wounds, or strokes that arise from time to time. |

|

Mal aire |

A disease caused by strong winds experienced while the person walks down a hill, by contact with cold air when the person leaves a sheltered place, or when a person walks through cemeteries or places where there are hidden treasures. |

Dizziness, headache, vomiting, stomach pain. The patient suffers body deterioration. |

|

Mal hecho |

This disease is caused by damage that a person intentionally inflicts on another individual. The diseases that are manifested are organic and psychological, emphasizing envy and jealousy. |

The patient suffers personal misfortunes, accidents, death of loved ones, and financial losses. This leads to depression. |

| Shuka | This disease is the so-called mal de ojo. It is caused by a person directed a forceful gaze toward someone else. In this case, the disease occurs without maliciousness. Otherwise, shuka occurs with bad intention. | Fainting, nervousness, pale face, headache, sadness, behavioral, and personality changes. Children are more prone to this disease. |

Today, it is not common to hear of certain diseases that are believed to be caused by malos espiritus because they are considered fantasy or superstition by scientific medicine and by those outside the Saraguro community. Therefore, the present study underlines the fact that valuable ancient medical knowledge is being lost because of acculturation.

According to yachak Polibio Japón Cango, some diseases known by elderly Saraguro healers, such as huairashcamanta (a disease caused by malos espiritus in people who walk by places where people have died), huatucayashca (a disease that occurs mostly in pregnant women who travel or sleep in enchanted hills), or mancharishca (susto), have lost their relevance. This irrelevancy is the result of the acculturation process that the Saraguro members have undergone in the last 50 years. Consequently, the main goal of the present study is to recover ancient Saraguro knowledge.

Empirical treatment methods

Limpia in the Saraguro community

Limpia (healing treatment) is performed to remove a person’s negative energy and to remove the effect of the shuka (the so-called mal de ojo). According to Saraguro healers, certain diseases are caused by the negative energy of another person. Limpia is the first empirical treatment provided; after limpia, a person can heal fully without further necessary treatment. Table 5 presents some plants that are considered powerful for this treatment.

Table 5.

Main plants used during limpia in the Saraguro community

| Common name | Scientific name | Species voucher | Part used |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Santa María silvestre |

Diplostephium macrocephalum S.F. Blake |

PPN-pi-009 |

The entire plant |

| ASTERACEAE | |||

|

Santa María de huerta |

Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Sch. Bip. |

PPN-pi-014 |

The entire plant |

| ASTERACEAE | |||

|

Poleo |

Minthostachys mollis (Kunth) Griseb. |

PPN-pi-007 |

The entire plant |

| LAMIACEAE | |||

|

Poleo de llano |

Clinopodium sp. |

PPN-pi-004 |

The entire plant |

| LAMIACEAE | |||

|

Shuyu rosas de cerro |

Eryngium humile Cav. |

PPN-pi-013 |

The entire plant |

| APIACEAE | |||

|

Laurel grande |

Myrica parvifolia Benth. |

PPN-pi-015 |

Blooming branches |

| MYRICACEAE | |||

|

Romero |

Rosmarinus officinalis L. |

PPN-pi-019 |

Branches |

| LAMIACEAE | |||

|

Ruda |

Ruta graveolens L. |

PPN-pi-010 |

The entire plant. |

| RUTACEAE | |||

| White wandug |

Brugmansia candida Pers. |

PPN-pi-021 |

Branches |

| SOLANACEAE | |||

| Pink wandug |

Brugmansia suaveolens (Willd.) Bercht. & J. Presl |

|

Branches |

| SOLANACEAE | |||

| Red wandug |

Brugmansia sanguinea (Ruiz & Pav.) D. Don |

|

Branches |

| SOLANACEAE | |||

|

Marco cari and marco warmi |

Ambrosia artemisioides Meyen & Walp |

PPN-pi-001 |

Branches |

| ASTERACEAE | |||

| Cholo valiente |

Tagetes terniflora Kunth |

PPN-pi-017 | Branches |

| ASTERACEAE |

During limpia, a few branches of each plant are used to form two bunches. One bunch is held in each hand. The cleansing is conducted from the top of the body to the bottom while the healer and patient repeat specific prayers. Depending on the case and the possibility of procuring the indicated species, either all appropriate plants are used or only those that are easily accessible are used.

The plant species used for limpia vary depending on the disease; for example, when limpia is employed to treat mal aire, poleo (Clinopodium sp.), turpec (Solanum oblongifolium Dunal.), shadán (Baccharis obtusifolia Kunth), ajenjo (Artemisia sodiroi Hieron.), limoncillo (Siparuna muricata (Ruiz & Pav.) A. DC.), laurel (Myrica parvifolia Benth.), marco (Ambrosia artemisioides Meyen & Walp.), romero (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) ushku sacha (Loricaria thuyoides (Lam.) Sch. Bip.), chilca negra (Baccharis sp.), and cholo valiente (Tagetes terniflora Kunth) are used.

To increase the limpia’s effect, an infusion of chichira (Lepidium chichicara Desv.), ruda (Ruta graveolens L.), poleo chico (Minthostachys mollis (Kunth) Griseb.), and shadán (Baccharis obtusifolia Kunth) is administered.

According to Isabel Medina Tene, Saraguro yachak, the cleansing rituals must be performed by people who have good physical, spiritual, and emotional strength, as the power of the healing ritual depends on the nature of the plants used and the person who performs the ritual.

Among the Kichwa peoples of Ecuador (Cañar and Cuenca), limpia and a diagnostic method using the Andean guinea pig (Poronccoy cavia Pchudii) are very popular. However, according to our research, these methods are not commonly used in the Saraguro region.

Soplada

After limpia, the yachak blows a special preparation known as cargado (an alcoholic extract of plants possessing certain power, together with a sugar cane liquor called aguardiente and various perfumes, such as Agua Florida) on the person. The composition of cargados varies depending on the disease and the yachak who prepares them. For example, to treat shuca, a cargado containing Santa María. (Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Sch. Bip., ruda (Ruta graveolens L.), duamaric (Tibouchina laxa (Desr.) Cogn.), Shuyu rosas (Eryngium humile Cav.), Killu rosas (Tagetes erecta L.), and cholo valiente (Tagetes terniflora) is prepared.

Cargado can also be applied by external rubbing on the affected part. For example, in the case of fractures, shock, or muscular strains, a cargado containing cararango (Lobelia sp.), ruda (Ruta graveolens L.), Killu rosas (Tagetes erecta L.), tobacco (Nicotiana spp.), valeriana (Valeriana pyramidalis Kunth), and cholo valiente (Tagetes terniflora Kunth) is used.

To treat susto, after limpia, the Saraguro healer blows over the patient a caragado called Ishpingo that contains cararango (Lobelia sp.), Santa Maria (Tanacetum parthenium (L.) Sch. Bip.), female and male Trencilla (Lycopodiaceae spp.), toronjil (Melissa officinalis L.), and Palo santo (Bursera graveolens L.). This cargado is prepared by maceration in water or aguardiente.

In the Saraguro community, it is common for every family to prepare its own cargado and use it to treat mal aire or susto. According to different investigations conducted in South America, this cargado is characteristic to the Andean indigenous people [25-27].

Using plants as a purgative

The use of various purgative plant extracts clears the organism; this purge may be the reason for a person’s healing or may prepare the body for further treatment. Trencillas (Lycopodiaceae spp.) mixed with other plants, such as cactus aguacolla or San Pedrillo Echinopsis pachanoi (Britton & Rose) Friedrich & G.D. Rowley are used in purgative preparations.

Elements used in rituals performed by yachakkuna

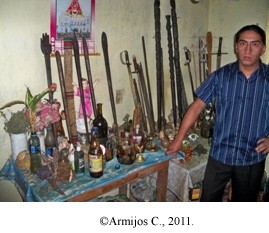

In the ritual ceremonies known as mesas or mesadas, certain elements are used along with sacred plant species [3,17,18,25]; the total number of items reported by Saraguro yachakkuna are indicated in Table 6 and Figure 2. The elements used vary according to each yachak; some mesas are very simple (Figure 3A), and they are held in lakes or enchanted hills (Figure 3B).

Table 6.

Main items used in healing rituals in the Saraguro community

| Elements of the mesa | Description |

|---|---|

| Sword or machete |

These items are used as a defense against enemies or negative energies that threaten the mesa. |

|

Bastón de mando |

This item represents the maximum power that is present in the ritual. These canes have magical powers: if they are passed through the body of a person, they clean the person of negative energies. |

| Stones |

Stones serve to cleanse a person and remove his/her negative energies. Some are archaeologically significant and appear to have more power than normal stones. |

| Shells |

Shells are used as vessels for ingesting the psychoactive species extract. |

| San Pedro cactus beverage |

Sacred drink used to achieve an ecstatic state and the desired contact with the gods and the supernatural. |

| Sugar |

Sugar is the symbol of the good, the sweet, the blooming. It is used to prepare a drink with lime juice and carnation flowers that finishes the mesa and completes the ritual. |

| Macerated tobacco |

Tobacco leaves are extracted in water or alcohol and perfumes. This extract is inhaled to enhance the effect of the San Pedro beverage. |

| Extract of wild sacred plants |

An extract made from wild sacred plants known as wamingas and trencillas (Lycopodiaceae spp.). It has the power to cure and remove negative energies. |

|

Aguardiente |

Distilled from sugar cane, this item is used as an offering during the ritual. |

| Agua Florida and perfumes |

These items remove the negative energy during soplada. In this manner, the environment, mesa, yachak, and patients are cleansed. |

| Holy water |

Holy water removes negative energy during the ceremony. For the yachak, holy water is pure and fresh water that has been collected from lagoons and sacred lakes. |

|

Rienda |

This item is a rope made of cattle tail hair. It represents a sacred element that removes negative energy and diseases while the patient passes it through his/her body, simulating an external cleaning. |

| Candle | In the flame of the candle, some visionary yachakkuna can see the health and welfare of a patient. The intensity of the flame indicates the patient’s problem and his/her future. |

Figure 2.

Orlando Leonidas Gualán, chairman, Council of Healers, Saraguro, beside a healing mesa in 2011.

Figure 3.

Saraguro healing mesas. (A) José María Gonzáles, visionary yachak, Tambopamba. (B) Healing ritual in San Lucas.

Use of psychoactive species

Use of San Pedro cactus

San Pedro cactus, also called aguacolla or San Pedrillo, Echinopsis pachanoi (Britton & Rose) Friedrich & G.D. Rowley, is one of the most common sacred plants employed by Saraguro yachakkuna. Aguacolla is a plant that protects the matrimonial union, the family, and the peaceful coexistence of parents and children; therefore, it is cultivated close to the house.

For hallucinogenic purposes, San Pedro cactus is used as a beverage during magical-religious ceremonies to attain altered states of consciousness that allow the yachak to recognize the patient’s condition and determine the possible treatment. According to Madsen [28] and Schultes & Hofmann [3], in South America, the plant has an important cultural history, as the indigenous population of Ecuador and Peru [27,29,30] has used this plant for its hallucinogenic effects since pre-Columbian times.

Another property attributed to the beverage is the purge that clears the organism. Ingesting the beverage may cause vomiting or diarrhea, which removes the agents that affect patient’s health. After drinking the beverage, some people suffer an emotional effect that leads to tears. This emotional release is considered a form of spiritual healing. For several of the consulted yachakkuna, whether a person has these symptoms is related to his or her biological and psychological constitution, the provided dose, and the patient’s disease state.

In the Saraguro community, mesas with San Pedro cactus are performed for several purposes: (i) to regain health when the person has a certain disease for which conventional medical treatment was not effective; (ii) to gain money; (iii) to regain the love of someone; and (iv) to find lost animals or objects.

Table 7 presents the main applications attributed to this plant in Saraguro community. The reported uses of San Pedro cactus to cure supernatural diseases, such as shuka and nervous system alterations, are in agreement with previous studies conducted in Saraguro community [15,16].

Table 7.

Uses of San Pedro cactus in the Saraguro community

| Uses | Preparation | Administration |

|---|---|---|

| To induce visions (oral) |

The cactus pulp is cooked for 7 h until a viscous consistency is obtained. |

It is drunk (one or two glasses). |

| To induce visions (inhaled) |

The cactus is cooked and extracted with trencillas, wuamingas (Lycopodiaceae spp.), tobacco leaves, and Agua Florida. |

It is administered through the nose using small shells. The process is led by the yachak. |

| As a purgative |

Fresh San Pedro juice is mixed with other plant preparations, known as cargados. |

The beverage is drunk while the patient is in a fasting state before breakfast; the process is repeated for three days. |

| To treat shuka |

The pulp juice is mixed with an extract of tobacco and cararango (Lobelia sp.). |

The extract dose drunk by the patient is approximately 5 ml. |

| To treat anxiety |

One San Pedro leaf is added to 1 liter of infusion prepared with plants that are used to treat anxiety. |

The infusion is drunk for several days until the patient recovers. |

| As an anti-inflammatory or wound disinfectant. | The cooked pulp is used as bandage. | The affected part is washed, and the bandage is placed. |

Many Saraguro yachakkuna experiment with different types of cactus that, according to their criteria, vary depending on the number of edges; the San Pedro cactuses most commonly used have six, seven, or eight edges and are collected in the surrounding Saraguro areas, such as Loja, Catamayo, and part of the El Oro Province. The most desired type is the seven-edged Echinopsis pachanoi, which has a high content of mescaline and other alkaloids. According to Madsen [28], these toxic substances are used by the plant to prevent animals from consuming its branches. The active principle of the San Pedro cactus is mescaline [31]. Although there are no studies on the chemistry of the drink used by Saraguro, the estimated concentration of mescaline in a drink ingested during a traditional medicine session in Perú was 50-70 mg [25].

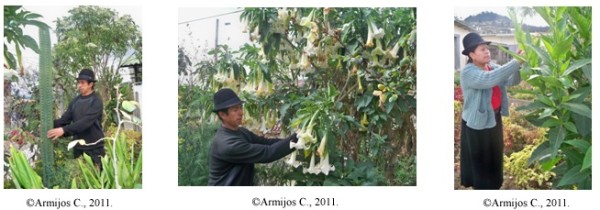

Use of floripondios plants

The Brugmansia plants are considered sacred by the indigenous peoples of South America [32,33]. The Saraguro yachakkuna call these species wandug or floripondios. According to Schultes & Hofmann [3], the ancient Andean culture knew of at least six Brugmansia species. Four distinct species can be found in the Saraguro community area: one with red flowers, called red wandug (Brugmansia sanguinea); one with yellow flowers (Brugmansia aurea); one with white flowers, called white wandug (Brugmansia candida); and one with pink flowers, called pink wandug (Brugmansia suaveolens). Some of these species have been previously used in different indigenous populations of Ecuador [34] and Peru [33,35,36]. The use of B. aurea and B. sanguinea by other Kichwa communities in Central Andean Ecuador as psychoactive and narcotic species has been documented [37,38].

Table 8 presents the uses of these sacred species by the Saraguro yachakkuna. Most Saraguro homes have a floripodio plant in the garden to protect their inhabitants from negative energies or witchcraft.

Table 8.

Uses of wandug ( Brugmansia spp.) in the Saraguro community

| Species | Common name | Traditional use | Preparation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Brugmansia aurea Lagerh. SOLANACEAE |

Wandug or yellow floripondio |

They are used during limpia to treat shuka, mal aire or susto. |

A bouquet is made with Brugmansia branches, Santa María de huerta, shuyu rosas de cerro, laurel grande, ruda, marco cari and cararango. |

|

Brugmansia sanguinea (Ruiz & Pav.) D. Don |

Wandug or red floripondio |

They are used on humans and animals. These species are applied externally. |

|

| SOLANACEAE | |||

|

Brugmansia candida Pers. |

Wandug or white floripondio |

To treat rheumatic pain. |

Brugmansia leaves are cooked with other plants that are used for the same purposes. |

| SOLANACEAE | |||

|

Brugmansia suaveolens (Willd.) Bercht. & J. Presl |

Wandug or pink floripondio | They are taken in baths. | |

| SOLANACEAE |

When the San Pedro cactus does not have the desired hallucination result, the Brugmansia flower is added to induce intoxication; this use has also been reported in Peruvian folk healing rituals [36,39,40]. However, the plant’s use for this purpose among the Saraguro yachakkuna is not generalized. According to a Kichwa myth, a beautiful young woman (goddess) was insulted by a vain man; as a vengeance, she placed a powder made of red wandug leaves and flowers into a glass of chicha and gave it to him to drink. The man lost his voice forever, as this plant is considered very dangerous and may have negative effects if used inappropriately. Muñoz Bernard [22] notes that the Zhal indigenous group in the province of Cañar use chicha (maize liquor) and floripondios liquor to make a person become dizzy and dream like a dead person. This finding may be proof of the plant’s use as a psychoactive specie by other groups in the Andean region of Ecuador.

In a study regarding the use of psychoactive species in Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, Kvist [41] reports that the Brugmansia spp. are used in place of the San Pedro cactus in Andean regions where the San Pedro cactus is difficult to acquire.

Because of its importance as a medicinal specie in healing rituals, wandug is cultivated by yachakkuna in their gardens; this is a common practice in various Andean communities [33,41,42].

Tobacco use

Tobacco (Nicotiana spp.) is a sacred specie with an important role in Saraguro rituals. During ceremonies, tobacco can be administered as liquor or it can be inhaled. It is occasionally smoked during the rituals; the tobacco powder obtained from the dry leaf is aspired or blown with inhalers to induce stimulant and sedative effects.

The narcotic and hallucinogenic effect of tobacco has been mentioned in previous studies regarding the traditional medicine of other indigenous groups [43-46]. During these rituals, various species of tobacco are used, including Nicotiana rustica, which is called Sacha tobacco in the Kichwa language, and Nicotiana tabacum. According to yachakkuna, Nicotiana rustica has a greater psychoactive effect than Nicotiana tabacum; this belief is in accordance with the beliefs of traditional shamans from Mexico and South America [45].

The sacred species most commonly used by Saraguro healers to cure supernatural diseases and in their healing rituals are San Pedro cactus, wandug, and tobacco (Figure 4). Psychoactive preparations can be obtained from these plants when used alone or mixed with other vegetable additives. These products can be taken orally or inhaled.

Figure 4.

San Pedro cactus, white wandug, and tobacco. Medicinal species demonstration garden, Saraguro Hospital.

Nasal administration

According to the aforementioned world view of disease, in the Saraguro community, the nasal absorption of macerated plants has a dual meaning: when absorbed through the right nostril, the plant serves to receive positive energy and to improve the person’s mood; when absorbed through the left nostril, the plant serves to drive out negative energy from the person. Administration by inhalation is faster and more efficient than oral administration because of better absorption in the nasal capillaries; in this manner, the degradation of the substance in the mouth and intestine is avoided [47]. According to previous studies, this practice has been used in the Central Andes for more than 4,000 years [48,49].

Final considerations

To preserve the traditional Saraguro knowledge about empirical medicine, the Loja Department of Provincial Health and the Healers Council of Saraguro (Consejo de Sanadores de Saraguro) have created a school of traditional indigenous medicine where wise hampiyachakkuna share their empirical knowledge and select apt young Saraguro apprentices to continue their training process. In the Saraguro community, knowledge about the uses of sacred and psychoactive medicinal plants is passed orally from generation to generation, mainly from parents to children or a familiar member who is an expert in traditional medicine.

Publications regarding the use of plants in the southern region of Ecuador in indexed journals include Finnerman [9], Béjar, Bussmann [50], Bussmann and Sharon [17], and Cavender and Alban [18]. None of these publications cite the use of psychoactive species for visionary, magical, or religious purposes by the Saraguro yachakkuna.

Conclusions

The current traditional health system in Saraguro community is the cultural expression of the Saraguros’ presence as an Andean group in southern Ecuador: it represents their character as indigenous group, their ability to survive as a community despite strong external pressure, and the desire to maintain their ancient healing heritage.

The modern-day hampiyachakkuna represent a synthesis of the ancient knowledge inherited from their ancestors and the knowledge gained during the acculturation process they have undergone. The latter factor represents a distortion of the richness of the original healing system. The disease treatments used in Saraguro communities located far away from the city respect and follow the ancient traditional methods with more rigor than is observed in communities located in urban areas.

It has been confirmed that yachakkuna from Saraguro community use psychoactive species, such as San Pedro cactus Echinopsis pachanoi, wandug (Brugmansia spp.), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.), and other vegetable additives, during their religious-magical rituals and healing ceremonies to treat physical, mental, emotional, and supernatural diseases. The present study represents a first step in the recovery process of traditional Saraguro medicinal knowledge conducted in collaboration with the Saraguro community yachakkuna. It represents a starting point for future studies and state programs that will promote the Saraguro culture and the sustainable development of Saraguro medicinal and biological resources.

Consent

Permissions were provided by all participants in this study, including the chairman, Council of Healers Orlardo Leonidas Gualán (Figure 2), José Maria Gonzales shown in the photos (Figure 3(A)), Daniel Guamán and Isabel Gualán (Figure 4). They have declared that they have no objection to the publication of their pictures in the journal. The consent was obtained from the participants prior to this study being carried out. The photographers (Daniel Guamán and Chabaco Armijos) transferred the copyrights to the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CA conducted the fieldwork. CA, IC, and SG designed the study, performed the data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Chabaco Armijos, Email: cparmijos@utpl.edu.ec.

Iuliana Cota, Email: micota@utpl.edu.ec.

Silvia González, Email: sgonzalez@utpl.edu.ec.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to the interviewed Saraguro yachakkuna and particularly to Isabel Medina, Polibio Japón Cango, Angel Medina, Aurelia Quizphe, Inés Puchaicela, Asunción Zhunaula, Segundo Paqui, Vicente Andrade, Rosa Zapata, Mercedes Medina, Mariana Guamán and Orlando Gualán for their collaboration and for sharing their knowledge and wisdom about the use of sacred psychoactive flora of the area. We also thank Bolívar Merino, curator of the Universidad Nacional de Loja (UNL) Herbarium for the classification of plant species. SENESCYT and the Department of Chemistry of the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja are acknowledged for their support. We thank Dr. José Cartuche, MSP-DPSL, Mercedes Guamán, Isabel Gualán, Rosa Quishpe, Janneth Ludeña, Luz Lozano and Daniel Guamán, employees at the Subproceso de Salud Intercultural program, for their openness and collaboration in the research programs concerning the recovery and validation of Saraguro healers’ ancestral medicinal treatments, for delivering notes and medical cards on traditional medicine in Saraguro, and for the photographs that are presented in the present work. Special greetings are extended to Antonio Lozano, José Miguel Andrade, Leonidas Chalán, Ana Guamán, Carlos Gualán and Manuel Andrade for facilitating the communication with the Saraguro community. Special thanks are extended to Diego Allen-Perkins for his support.

References

- La Barre W. The Peyote Cult. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Furst PT, Ramírez Gómez JA. Los Alucinógenos y la Cultura. Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Schultes RE, Hofmann A, Ralsch C, Blanco A, Guzmán G, Acosta S. Plantas de Los Dioses: Las Fuerzas Mágicas de las Plantas Alucinógenas. Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J. Medicina Indigenista. Argentina: Jorge Rubén Alonso; 2010. La cosmovisión indigenista; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo P, Escaleras R. La Medicina Tradicional en el Ecuador. Corporación Editora Nacional: Quito; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cabieses F. The magic plants of ancient Perú. Atti del V Congresso Nazionale della Società Italiana di Fitochimica. 1990. p. LP2.

- Valencia R. Libro Rojo de las Plantas Endémicas del Ecuador. Ecuador: Herbario QCA, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barthlott W, Lauer W, Placke A. Global Distribution of Species Diversity in Vascular Plants: Towards a World Map of Phytodiversity. Berlin: Erdkunde; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Finnerman R. Experience and expectation: conflict and change in traditional family health care among the Quichua of Saraguro. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17:1291–1298. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tene V, Malagon O, Finzi PV, Vidari G, Armijos C, Zaragoza T. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in Loja and Zamora- Chinchipe, Ecuador. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;111:63–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belote J. Changing Adaptive Strategies among the Saraguros of Southern Ecuador. Abya-Yala Editions: Quito; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Uhle M. Max Uhle, 1856-1944, a Memoir of the Father of Peruvian Archaeology, by John Howland Rowe. [Appendix A. The Aims and Results of Archaeology, by Max Uhle. Appendix B. Letters from Argentina and Bolivia. 1893-1895, by Max Uhle] California: University of California Press; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Japón Gualán R. ¿Quién es un Runa? España: Diputación de Córdoba, Oficina de Cooperación Internacional; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pohle P, Gerique A. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Biodiversity Management in the Andes of Southern Ecuador. Geographica Helvetica, Swiss Journal of Geography. 2006. pp. 275-285.

- Andrade JM, Armijos C, Malagón O, Lucero H. Plantas Silvestres Empleadas por la etnia Saraguro en la Parroquia San Lucas. UTPL: Loja, Ecuador; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- MSP-DPSL. Cartilla de Salud Reproductiva de la Cultura Saraguro. In Book: Cartilla de Salud Reproductiva de la Cultura Saraguro. Ecuador: Integraf; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann R, Sharon D. Traditional medicinal plant use in Loja province, Southern Ecuador. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:44. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavender A, Alban M. The use of magical plants by curanderos in the Ecuador highlands. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MSP-DPSL. Apuntes sobre Medicina Ancestral del Pueblo Saraguro. Ecuador: Integraf; 2010. Apuntes sobre medicina ancestral del pueblo saraguro; pp. 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- MSP-DPSL. El Uso de las Plantas Medicinales en las Prácticas Ancestrales de Curación y/o Sanación de Enfermedades del Pueblo Saraguro. Ecuador: Industrial Gráfica Amazonas; 2003. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- MSP-DPSL. Programa de Apoyo a la Salud en Ecuador (PASSE) Ecuador: MSP; 2008. pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Bernard C. Enfermedad Daño e Ideologia: Antropologia Medica de los Renacientes de Pindiling. Editorial Abya Yala: Quito; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade JM. Estudio Etnobotánico de Plantas Medicinales Empleadas por la Etnia Saraguro en la Parroquia San Lucas del Cantón Loja, Provincia de Loja. UTPL, Escuela de Ingeniería Agropecuaria: Ecuador; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez N, Muñoz S. Levantamiento Etnobotánico de las Especies Medicinales y Artesanales del Cantón Saraguro, Provincia de Loja. UTPL: Ecuador; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reyna V. Memorias del Taller Binacional sobre Medicina Tradicional e Indígena. Ecuador: Loja; 2002. Uso del cactus San Pedro (Echinopsis pachanoi) en medicina tradicional Peruana; pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Joralemon D, Sharon D. Sorcery and Shamanism: Curanderos and Clients in Northern Peru. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sharon D. In: En el Nombre del Señor: Shamanes, Demonios y Curanderos del Norte del Perú. Millones L, Lemlij M, editor. Lima: Australis S.A; 1994. Tuno y sus colegas: notas comparativas; pp. 128–147. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen J. Flora of Ecuador-Cactaceae. Berlings: Sweden; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sharon D. Shamanismo y el Cacto Sagrado - Shamanism and the Sacred Cactus. San Diego Museum Papers: San Diego; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- de Rios ML D. Trichocereus pachanoi: a mescaline cactus used in folk healing in Peru. Econ Bot. 1968;22:191–194. doi: 10.1007/BF02860562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pummangura S, McLaughlin JL, Schiffendecker RC. Cactus alkaloids. LI. Lack of mescaline translocation in grafted Trichocereus. J Nat Prod. 1982;45:215–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bristol ML. Tree Datura drugs of the Columbian Sibundoy. Botanical Museum Leaflets. 1969;22:165–227. [Google Scholar]

- De Feo V. The ritual use of Brugmansia species in traditional Andean medicine in northern Peru. Econ Bot. 2004;58:221–229. doi: 10.1663/0013-0001(2004)58[S221:TRUOBS]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen P, León-Yanez S. Catalogue of the vascular plants of Ecuador. Monographs in Sistematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden. 1999;75:1–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Brako L, Zarucchi J. Catalogue of the flowering plants and gymmnosperms of Peru. Monographs in Sistematic Botany from the Missouri Botanical Garden. 1993;45:1–1286. [Google Scholar]

- De Feo V. Medicinal and magical plants on northern Peruvian Andes. Fitoterapia. 1992;63:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Cerón C, Montalvo C. Etnobotánica de la comunidad Alao, zona de influencia del Parque Nacional Sangay. Cinchonia. 2002;3:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ceron C, Quevedo A. Etnobotánica del Putzalagua. Cotopaxi, Ecuador. Cinchonia. 2002;3:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Sharon D. In: Flesh of the Gods. The Ritual Use of Hallucinogens. Furst P, editor. London: George Allen & Unwin; 1972. The San Pedro cactus in Peruvian folk healing; pp. 114–135. [Google Scholar]

- De Feo V. Ethnomedicinal field study in northern Peruvian Andes with particularreference to divination practices. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;85:243–256. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(03)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvitst L, Morales M. Botánica Económica de los Andes Centrales. La Paz: Universidad Mayor de San Andrés; 2006. Plantas psicoactivas; pp. 294–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood T. The ethnobotany of Brugmansia. J Ethnopharmacol. 1979;1:147–164. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(79)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J. In: Handbook of South American Indians, Bulletin of the Bureau of American Ethnology, no. 143(5) Steward J, editor. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1949. Stimulants and narcotics; pp. 525–558. [Google Scholar]

- Elferink J. The narcotic and hallucinogenic use of tobacco in pre-Colombian Central America. J Ethnopharmacol. 1983;7:111–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(83)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiser S. The Fascinating World of the Nightshades. Tobacco, Mandrake, Potato, Tomato, Pepper, Eggplant, Etc. New York: Dover Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbert J. Does pharmacology corroborate the nicotine therapy and practices of South American Shamanism? J Ethnopharmacol. 1991;32:179–186. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(91)90115-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet P. A multidisciplinary overview of intoxicating snuff rituals in the western hemisphere. J Ethnopharmacol. 1985;13:3–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(85)90060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin De Ríos M. Hallucinogens: Cross Cultural Perspectives. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pochettino M, Cortilla A, Ruiz M. Hallucinogenic snuff from Northwestern Argentina: Microscopical Identification of Anadenanthera colubrina var. Cebil (Fabaceae) in powdered archaeological material. Econ Bot. 1999;53:127–132. doi: 10.1007/BF02866491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Béjar E, Bussmann R, Roa C. Herbs of Southern Ecuador: A Field Guide to the Medicinial Plants of Vilcabamba. Spring Valley, CA: Latino Herbal Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]