ArsH from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was overproduced, purified and crystallized. Diffraction data were processed to a resolution of 1.6 Å. The crystals belonged to the tetragonal space group I4122, with unit-cell parameters a = b = 127.94, c = 65.86 Å.

Keywords: ArsH, Synechocystis, arsenic

Abstract

ArsH is an NADPH-dependent flavin mononucleotide reductase and is frequently encoded as part of an ars operon. The function of the arsH gene remains to be characterized. Crystallization and structural studies may contribute to elucidating the specific biological function of ArsH associated with arsenic resistance. ArsH from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 was overproduced, purified and crystallized. Crystals were obtained by the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method. Diffraction data were collected and processed to a resolution of 1.6 Å. The crystals belonged to the tetragonal space group I4122, with unit-cell parameters a = b = 127.94, c = 65.86 Å and one molecule in the asymmetric unit. Size-exclusion chromatography and molecular-replacement results showed that the ArsH formed a tetramer. Further structural analysis and comparison with ArsH from Sinorhizobium meliloti will provide information about the oligomerization of ArsH.

1. Introduction

Arsenic is one of the most toxic substances in the environment. It can exist as a variety of species such as arsenate [arsenic(V)], arsenite [arsenic(III)] and organic arsenicals. Nearly all bacteria and archaea harbour the arsenic-resistance (ars) operon which encodes at least three components: ArsR, ArsC and ArsB (Qin et al., 2006 ▶; Bhattacharjee & Rosen, 2007 ▶); among these ArsR is a repressor protein acting as a negative regulator of the ars operon, ArsB is an arsenite-specific efflux pump protein and ArsC is an enzyme that reduces arsenic(V) to arsenic(III). In Synechocystis and other organisms, ArsH is also part of the ars operon (López-Maury et al., 2003 ▶; Chang et al., 2007 ▶; Cai et al., 2009 ▶).

The function of the arsH gene remains to be characterized. ArsHs from Yersinia enterocolitica, Sinorhizobium meliloti, Ochrobactrum tritici SCII24 and Lactobacillus acidophilus confer resistance to arsenicals (Neyt et al., 1997 ▶; Yang et al., 2005 ▶; Branco et al., 2008 ▶; Sinha et al., 2011 ▶), while ArsH from A. ferrooxidans or Synechocystis shows no arsenic resistance (Butcher et al., 2000 ▶).

The structural analyses of ArsH from S. meliloti and an apo form of ArsH from S. flexneri (Vorontsov et al., 2007 ▶; Ye et al., 2007 ▶), as well as enzymatic assays and protein sequence analysis, have demonstrated that ArsH is a member of the NADPH-dependent FMN (flavin mononucleotide) reductase family. It has been demonstrated that ArsH from S. meliloti acts as an azoreductase, while ArsH from A. ferrooxidans has ferric reductase activity and ArsH from Synechocystis is a quinone reductase (Mo et al., 2011 ▶; Hervás et al., 2012 ▶). To date, there is no direct biochemical evidence to show how ArsH confers arsenic resistance. Since ArsH is part of the ars operon and is widely distributed in bacteria, we hypothesize that ArsH provides a specific biotransformation mechanism in arsenic resistance.

The ArsH protein from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 has 74% sequence identity to ArsH from S. meliloti which crystallizes as a tetramer. It has been proposed that the termini play an important role in tetramer formation, and that tetramer formation may be needed for functioning. The salt bridges or hydrogen bonds between helix α5 and the terminal residues of another subunit may be essential for tetramer formation. However, Synechocystis ArsH is 27 residues shorter at the N-terminus compared with S. meliloti ArsH. This raises the question of whether the Synechocystis ArsH still forms a tetramer. If not, will this affect its function?

In this study, we report the overproduction, purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray studies of ArsH from the widely used experimental model organism Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. ArsH is a 206-residue protein with a mass of 23.7 kDa. Diffraction data were collected to a resolution of 1.6 Å.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Overproduction and purification

The arsH gene from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 was amplified by PCR, cloned into the plasmid pET-22b and then expressed with a 6×His tag in the Escherichia coli strain Rosetta. Cells were grown overnight at 16°C after adding 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at an OD600 of 0.6–0.8 to induce the overproduction of ArsH. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000g and 4°C for 15 min and resuspended in buffer A (20 mM HEPES, 500 mM NaCl pH 7.2). After sonication, the lysate was centrifuged at 13 000g and 4°C for 1 h. The supernatant was loaded onto an Ni2+-charged resin (GE Healthcare), washed with 20 mM imidazole in buffer A and then eluted with 15 ml buffer A containing 500 mM imidazole. ArsH was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad16/600 Superdex 75 prep-grade column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A. The elution volume of ArsH was then compared with the elution profile of molecular-mass standards to investigate the possibility of oligomerization (Fig. 1 ▶). The purified ArsH was analyzed by SDS–PAGE (Fig. 2 ▶). The purified protein was concentrated using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter (10 kDa molecular-mass cutoff).

Figure 1.

Analytical size-exclusion chromatography of purified ArsH on a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 prep-grade column. The standard curve for molecular mass is shown. V e of ArsH is 58 ml.

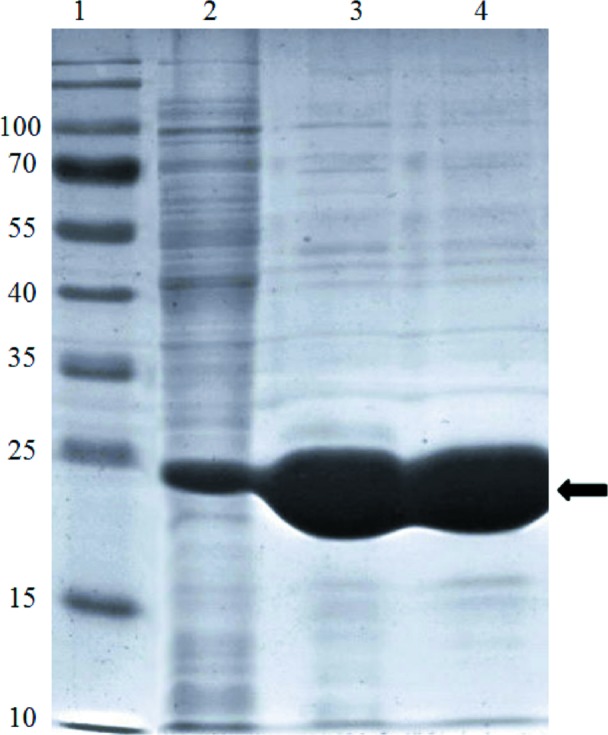

Figure 2.

The SDS–PAGE profile of ArsH is shown. Lane 1, molecular-mass markers (labelled in kDa). Lane 2, whole cells after induction by IPTG. Lanes 3 and 4, purified protein after Ni–NTA chromatography and size-exclusion chromatography, respectively. The arrow indicates the position of ArsH.

2.2. Crystallization

Purified ArsH was concentrated to 15 mg ml−1 in buffer A for crystallization. Crystallization experiments were set up in 96-well plates at 18°C using the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method by mixing equal volumes of protein solution and reservoir solution (0.5 µl of each) and equilibrating against 50 µl reservoir solution from a variety of crystallization screens from Hampton Research, Molecular Dimensions and Emerald Bio. After 3 d of incubation, crystals appeared in several conditions from Wizard, Index, Salt and BioXtal, and the best diffraction-quality crystals (Fig. 3 ▶) with maximum dimensions of 0.2 × 0.15 × 0.15 mm were obtained from condition No.3 of BioXtal (1.5 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M MES pH 6.5).

Figure 3.

Crystals of ArsH grown using 1.5 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M MES pH 6.5 as a crystallizing agent (maximum dimensions 0.2 × 0.15 × 0.15 mm).

2.3. Data collection and processing

Crystals were cryoprotected by soaking in well solution supplemented with 20% glycerol and then flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen before data collection. Diffraction data were collected at a wavelength of 0.9718 Å at −173°C on beamline BL17U of the Shanghai Synchrotron Research Facility (SSRF). A total of 360 images were collected with a crystal-to-detector distance of 200 mm and 0.5° oscillation range. Data were indexed and integrated using iMosflm (Battye et al., 2011 ▶) and scaled and merged using SCALA (Potterton et al., 2002 ▶).

2.4. Molecular replacement

The structure of Synechocystis ArsH was determined by the molecular-replacement method using AMoRe (Navaza, 2001 ▶) from CCP4 (Winn et al., 2011 ▶) and the published crystal structure of the ArsH protein from S. meliloti (PDB entry 2q62; Ye et al., 2007 ▶) as a search model.

3. Results and discussion

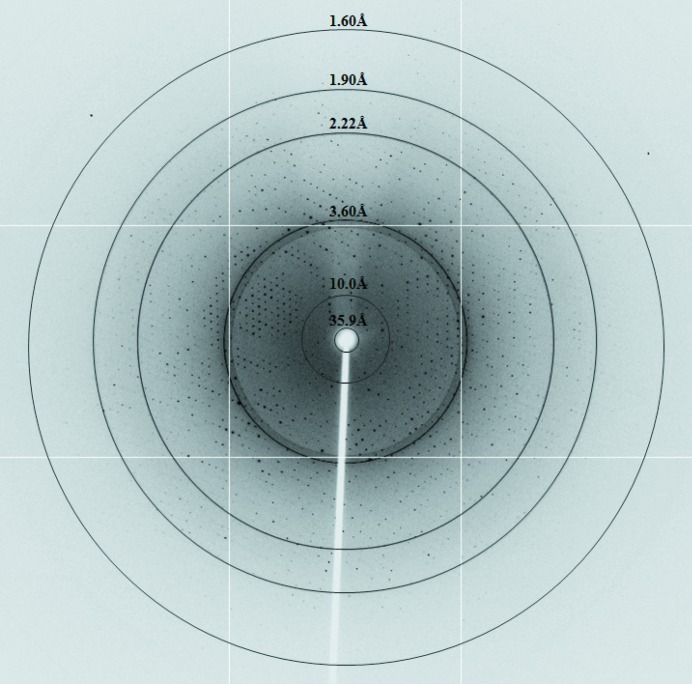

A C-terminally His-tagged ArsH from Synechocystis was overproduced in E. coli Rosetta strain and purified, yielding approximately 20 mg protein per litre of culture. The purified protein was tested for crystallization using a variety of commercial screens. Diffraction-quality crystals were obtained in 3 d from a drop consisting of 15 mg ml−1 protein, 1.5 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M MES pH 6.5. X-ray diffraction data were collected to a resolution of 1.6 Å (Fig. 4 ▶). The data-collection statistics are provided in Table 1 ▶. The ArsH crystals belonged to space group I4122, with unit-cell parameters a = b = 127.94, c = 65.86 Å. Assuming the presence of a single molecule of ArsH in the asymmetric unit, a V M of 2.84 Å3 Da−1 and a solvent content of 56.72% were calculated (Matthews, 1968 ▶). Using one molecule from the crystal structure of S. meliloti ArsH as a template, molecular replacement at 3.0 Å resolution yielded a solution with a correlation coefficient of 49.6% and an initial R factor of 45.4%. The model obtained by molecular replacement showed reasonable crystal packing and good electron density. Further refinement of the structure is in progress.

Figure 4.

X-ray diffraction image from an ArsH crystal.

Table 1. Data-collection and processing statistics for ArsH.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Diffraction source | SSRF |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9718 |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 200 |

| Resolution (Å) | 35.8–1.60 (1.63–1.60) |

| Space group | I4122 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = b = 127.94, c = 65.86 |

| Total No. of reflections | 274360 (14652) |

| Total No. of unique reflections | 36159 (1883) |

| Multiplicity | 7.6 (7.8) |

| Solvent content (%) | 56.72 |

| R merge † (%) | 8.5 (36.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 14.2 (4.8) |

R

merge =

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of the ith observation of unique reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean recorded intensity of reflection hkl over multiple recordings.

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of the ith observation of unique reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the mean recorded intensity of reflection hkl over multiple recordings.

Size-exclusion chromatography of the purified Synechocystis ArsH resulted in a single peak at 58 ml. Comparison with molecular-mass standards yielded a molecular mass of 95 kDa (Fig. 1 ▶), while SDS–PAGE indicated that the monomer molecular mass was about 24 kDa (Fig. 2 ▶). Thus, ArsH probably exists as a tetramer in solution. In agreement with a tetramer configuration, the molecular-replacement solution also showed that ArsH formed a tetramer by four crystallographic related molecules in the crystal structure. These four monomers showed crystallographic 222 symmetry, while the tetramer of S. meliloti ArsH shows noncrystallographic 222 symmetry (Ye et al., 2007 ▶). It has been previously proposed that the termini may play a role in maintaining the tetramer configuration, which might be functionally relevant (Ye et al., 2007 ▶). Our preliminary results showed that the Synechocystis ArsH still formed a tetramer, despite being 27 amino acids shorter at the N-terminus than the S. meliloti ArsH. The Synechocystis ArsH structure may also shed light on the detailed mechanism involved in arsenic biotransformation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors Yong-Guan Zhu and Xinquan Wang for helpful discussions. This work is supported by the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KZCX2-EW-QN410) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31270161).

References

- Battye, T. G. G., Kontogiannis, L., Johnson, O., Powell, H. R. & Leslie, A. G. W. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, H. & Rosen, B. P. (2007). Molecular Microbiology of Heavy Metals, pp. 371–406. Berlin: Springer.

- Branco, R., Chung, A. P. & Morais, P. V. (2008). BMC Microbiol. 8, 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Butcher, B. G., Deane, S. M. & Rawlings, D. E. (2000). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 1826–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cai, L., Rensing, C., Li, X. & Wang, G. (2009). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 83, 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.-S., Yoon, I.-H. & Kim, K.-W. (2007). J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17, 812–821. [PubMed]

- Hervás, M., López-Maury, L., León, P., Sánchez-Riego, A. M., Florencio, F. J. & Navarro, J. A. (2012). Biochemistry, 51, 1178–1187. [DOI] [PubMed]

- López-Maury, L., Florencio, F. J. & Reyes, J. C. (2003). J. Bacteriol. 185, 5363–5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mo, H., Chen, Q., Du, J., Tang, L., Qin, F., Miao, B., Wu, X. & Zeng, J. (2011). J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 21, 464–469. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Navaza, J. (2001). Acta Cryst. D57, 1367–1372. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Neyt, C., Iriarte, M., Thi, V. H. & Cornelis, G. R. (1997). J. Bacteriol. 179, 612–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Potterton, E., McNicholas, S., Krissinel, E., Cowtan, K. & Noble, M. (2002). Acta Cryst. D58, 1955–1957. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Qin, J., Rosen, B. P., Zhang, Y., Wang, G., Franke, S. & Rensing, C. (2006). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 2075–2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sinha, V., Mishra, R., Kumar, A., Kannan, A. & Upreti, R. K. (2011). Biotechnology, 10, 101–107.

- Vorontsov, I. I., Minasov, G., Brunzelle, J. S., Shuvalova, L., Kiryukhina, O., Collart, F. R. & Anderson, W. F. (2007). Protein Sci. 16, 2483–2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D. et al. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242.

- Yang, H.-C., Cheng, J., Finan, T. M., Rosen, B. P. & Bhattacharjee, H. (2005). J. Bacteriol. 187, 6991–6997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ye, J., Yang, H. C., Rosen, B. P. & Bhattacharjee, H. (2007). FEBS Lett. 581, 3996–4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]