Abstract

Objectives.

Although higher quality marriages are associated with better health outcomes, less is known about the mechanisms accounting for this association. This study examines links among marital/partner quality, stress, and blood pressure and considers both main and moderating effects.

Method.

Participants from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (N = 1,854; aged 57–85 years) completed in-person interviews regarding their marital/romantic partner relationships and perceived stress. Interviews included blood pressure assessments.

Results.

Linear regression models revealed no main effects of spousal/partner quality or stress on blood pressure. However, spousal/partner quality moderated the link between stress and blood pressure. Specifically, there were negative associations between stress and blood pressure among people reporting more confiding, less reliance, and greater demands from spouses/partners.

Discussion.

Findings highlight the complexity of relationship quality. Individuals appeared to benefit from aspects of both high- and low-quality spouse/partner relations but only under high levels of stress. Findings are inconsistent with traditional moderation hypotheses, which suggest that better quality ties buffer the stress–health link and lower quality ties exacerbate the stress–health link. Results offer preliminary evidence concerning how spousal ties “get under the skin” to influence physical health.

Key Words: Blood pressure, Cardiovascular health, Marriage, Relationship quality.

Marriage has significant beneficial effects on health and well-being. For instance, married individuals report better physical health (Lorenz, Wickrama, Conger, & Elder, 2006; Waite & Gallagher, 2000) and live longer than unmarried individuals (Gardner & Oswald, 2004; Manzoli, Villari, Pirone, & Boccia, 2007). Yet, significant diversity exists among married individuals in the quality of their marriages. Recent studies acknowledge that both negative (i.e., irritations and conflict) and positive (i.e., love and support) aspects of marriage have important implications for health and well-being (Slatcher, 2010). Positive quality marriages are associated with fewer psychological and physical health problems, whereas negative quality marriages are related to poorer health and well-being (Bookwala, 2005; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001). There is a debate in the literature, however, regarding whether relationship quality directly or indirectly influences health (Cohen, 2004; Uchino, 2004). The main effect model suggests that relationship quality has a direct association with health irrespective of stress levels (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988), whereas the moderating effect model suggests that relationship quality is particularly influential under higher levels of stress (Cohen & Wills, 1985).

There is also a debate in the literature regarding the specific biological mechanisms accounting for the links between relationships and health. The biopsychosocial model suggests that the cardiovascular system may be a significant pathway by which relationships influence overall health status (Seeman, 2003). However, studies of marital/partner quality, stress, and cardiovascular health typically involve younger married couples in a laboratory setting (Uchino, Birmingham, & Berg, 2010). We know little about these links in the larger population, and the associations between relationships and health may be even greater among older individuals for whom health problems are often present (Crimmins et al., 2005; Steptoe et al., 2003). This study is designed to address these gaps in the literature by examining associations among positive and negative marital/partner quality, perceived stress, and blood pressure among a large national sample of older adults. We address two aims: first, we examine the direct associations among marital/partner quality, stress, and blood pressure; second, we assess whether marital/partner relationship quality moderates the link between stress and blood pressure.

Theoretical Framework

The overarching theoretical framework guiding this study is referred to as the Biopsychosocial Model of Marriage, which incorporates three models: the main and moderating models of relationship quality and the biopsychosocial model of health (Engel, 1977; Lindau, Laumann, Levinson, & Waite, 2003). By including these three models, this framework provides an integrative approach to the marriage/health association and the mechanisms that may explain possible links. The main effect model suggests that there is a direct association between relationships and health irrespective of stress (House et al., 1988; Loucks et al., 2006; Seeman, 1996); for example, studies show that greater spousal quality predicts better physical and mental health. The moderating effect model states that spousal/partner relationships are particularly influential under stressful life circumstances: high-quality relationships may, for example, prevent stress or reduce negative reactions to it (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Uchino, 2004). At the same time, poor-quality relationships may exacerbate the influence of stress on health (August, Rook, & Newsom, 2007). Furthermore, according to the biospsychosocial model of health, social (e.g., relationship quality) and psychological factors (e.g., stress) influence overall health via biological pathways or mechanisms (Engel, 1977; Lindau et al., 2003; Seeman, 2003).

This study examines one particularly important biological pathway that may account for the associations among marital/partner quality, stress, and health: the cardiovascular system (Uchino, 2009). The cardiovascular system is particularly important to examine, as heart disease is the leading cause of death among older Americans (Delgado, Jacobs, Lackland, Evans, & Mendes de Leon, 2012). The cardiovascular system—the heart and blood vessels—is responsible for maintaining blood flow under changing environmental circumstances (Krantz & Falconer, 1995). Blood pressure is a measure of the functioning of this system (Crimmins & Seeman, 2000), defined as the force of blood against the walls of the blood vessels. Systolic pressure is the point of contraction representing the peak pressure, whereas diastolic pressure is the minimum pressure when the heart relaxes. Researchers have found that factors such as loneliness and increased stress are associated with increased systolic blood pressure (Hawkley, Masi, Berry, & Cacioppo, 2006; Steptoe et al., 2003), and chronic stress is associated with increased diastolic blood pressure (Piazza, Almeida, Dmitrieva, & Klein, 2010). It is particularly important to examine both systolic and diastolic blood pressure because the findings vary depending on the measurement, and either measure can be diagnostic of high blood pressure, that is, individuals can be considered hypertensive if systolic pressure is greater than 140mm Hg or diastolic pressure is greater than 90mm Hg (Williams, Pham-Kanter, & Leitsch, 2009).

It is also especially important to examine blood pressure among older adults, since blood pressure tends to increase with age and is associated with increased cardiovascular disease (Crimmins et al., 2005). Studies show that older people show greater systolic blood pressure reactivity to stress than do younger people (Uchino et al., 2010), although some research also suggests that high blood pressure may be protective among the oldest old (Goodwin, 2003). This study considers associations among marital/partner relationship quality, perceived stress, and blood pressure—both systolic and diastolic.

Main Effect of Relationship Quality and Stress on Health

The relatively small body of research concerning the direct links between positive marital quality and health has revealed mixed findings. Uchino and colleagues (1996) reviewed the literature and found that positive quality relations with family—typically, a spouse—was associated with improved function of the cardiovascular system, above the influence of health-related behaviors. Similarly, Holt-Lunstad, Birmingham, and Jones (2008) found that positive marital quality was associated with lower ambulatory blood pressure and overall stress. However, positive aspects of relationships are not always beneficial for health. Birditt and Antonucci (2008) examined associations between marital quality (positive, negative) and mortality among individuals aged 40-96. Somewhat surprisingly, participants who reported greater love from spouses at baseline had higher mortality rates.

Negative aspects of the marital tie are also directly linked with health outcomes in complex ways. Robles and Kiecolt-Glaser (2003) found that negative and hostile behaviors during marital conflict discussions were related to increased cardiovascular activity. Conversely, negativity may not always have harmful effects on health. Indeed, some studies show that greater negativity in relationships is associated with improvements in health behaviors, such as exercise (Krause, Goldenhar, Liang, Jay, & Maeda, 1993). Thus, the positive and negative aspects of spousal/partner ties may have complex associations with blood pressure.

Additionally, stress itself is thought to have a main effect on blood pressure. That is, increased stress is associated with higher blood pressure (Steptoe et al., 2003).

Moderating Effect of Relationship Quality on the Stress–Health Link

A small number of studies conceptualize positive marital quality as a buffer or moderator between stress and health outcomes. For example, Medalie and Goldbourt (1976) found that, among Israeli men aged 40 and older, support and love from a spouse buffered the influence of stress on future angina. Similarly, happily married working women recovered more quickly from work-related stress than their unhappily married counterparts (Saxbe, Repetti, & Nishina, 2008). In patients recovering from congestive heart failure, spouses who reported better quality relationships survived longer (Coyne et al., 2001). Bookwala (2011) examined the moderating role of spousal support and satisfaction on the link between poor vision and functional limitations among older adults and found inconsistent moderating effects. Greater marital satisfaction buffered the link, whereas greater marital support exacerbated the link between poor vision and functional limitations. Thus, it appears that greater positive quality relations can buffer or exacerbate the link between stress and health.

Few studies have examined the exacerbating effects of negative marital relationship quality on the stress–health link and results are mixed. Wang and colleagues (2007) found that, in female cardiac patients, thickening of coronary arterial walls worsened for those who experienced greater marital stress. In contrast, people with chronic illnesses who reported negative spousal relationships exhibited decreased mortality (Birditt & Antonucci, 2008). Antonucci, Birditt, and Webster (2010), however, found no exacerbating effects for negative spousal relationship quality in the association between chronic illness and mortality. These particular findings highlight the need for further understanding of the potential role of marital relationship quality as a moderator of the stress–health link.

Relationship Quality: Assessing Specific Behaviors

Research findings regarding positive and negative marital quality may be mixed because the behaviors assessed within the global measures of relationship quality have disparate associations with health. Recent studies indicate that item-level analyses show a more nuanced—and often more accurate—pattern of behavioral correlates (Hoppmann & Smith, 2007; Helson & Kwan, 2000). For example, Birditt and Antonucci (2008) examined relationship quality items separately and found that participants who reported greater spousal love had increased mortality, whereas low levels of spousal listening was associated with increased mortality, indicating that behaviors that are often included in an overall positive quality scale (i.e., greater love) may have opposite effects. Thus, analyzing behavior at the item level could alleviate some confusion in this area. In this study, we examine two positive quality items and two negative quality items separately to assess the degree to which individuals confide in their spouse, rely on their spouse for support, their spouse is demanding, and their spouse is critical. Because there is no research examining these behaviors and blood pressure specifically, we do not make predictions at the item level.

Present Study

This study examines associations among spousal/partner quality, stress, and blood pressure among older individuals. Because this study considers spousal quality as well as the quality of relations with live-in partners and romantic partners, we refer to quality as spousal/partner relationship quality. It is important to examine relationships beyond the spousal tie because older individuals are less likely to be in marital relationships compared with middle-aged individuals due to widowhood and divorce (Brown & Lin, 2012; Huyck, 2001; U.S. Census, 2010). Individuals who are widowed or divorced may choose not to remarry but to have romantic relations or cohabit, and these ties may have significant effects on their health (Chevan, 1996). This study addressed two questions:

1. What are the main effects of spousal/partner relationship quality (positive, negative) and stress on systolic and diastolic blood pressure?

We hypothesized that individuals with lower quality spousal/partner ties (i.e., lower levels of confiding in spouse/partner, and/or reliance on spouse/partner for help, or higher levels of spousal/partner demands and/or criticism) would have higher blood pressure. We also hypothesized that individuals who reported greater perceived stress would have higher blood pressure.

-

2. Does spousal/partner relationship quality moderate the associations between perceived stress and blood pressure?

We hypothesized that the association between perceived stress and blood pressure would be weaker among people with better quality spousal/partner relationships (i.e., higher levels of being able to confide in spouse/partner and/or being able to rely on spouse/partner for help, as well as lower levels of spousal/partner demands and/or criticism) and stronger among individuals with lower quality spousal/partner relationships.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants were from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP; Waite et al., 2010), a nationally representative probability survey of 3,005 individuals (52% women) aged 57–85 years. The sampling design involved multiple stages: two area stages for the selection of geographical regions, a household selection stage, and an individual selection stage in which one individual was selected from each household for the interview. Oldest old, men, African Americans, and Latinos were oversampled. The response rate was 75.5%.

Interviews were conducted from July 2005 to March 2006. Participants completed at-home, face-to-face interviews that included a computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) as well as a biomeasure component including blood pressure readings.

For the purpose of this study, we included only participants who were married, living with a partner, or those with a romantic partner (n = 2,013; 67% of the sample). One hundred and fifty-nine participants were missing data and were thus removed from the study. The final sample included 1,854 participants with complete data on all predictors, outcomes, and covariates. A total of 1,691 of participants were married (59% men), 55 were living with a partner (42% men), and 108 had romantic partners (63% men). Overall, participants were in relatively good health, reporting good-to-very good health on average (M = 3.39, SE = 0.04). Participants were distributed across three age groups: 47% were aged 57–64, 35% were aged 65–74, and 18% were aged 75–85 years. We conducted a logistic regression analysis to determine whether the complete sample varied from those with incomplete data among individuals with partners (spouses, cohabiting, or romantic). Individuals with complete data were more likely to be women and had higher self-rated health than individuals with incomplete data. There were no other significant differences for those with complete data on the demographics (age, education, race), spousal/partner relationship quality, or stress. See Table 1 for a description of the sample.

Table 1.

Sample Description of National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) Participants Who Were Married/Living With Partner or Romantically Involved With Complete Data (N = 1,854; weighted)

| % | M (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 66.87 (0.20) | |

| Married | 91 | |

| Cohabiting | 3 | |

| Romantic partner | 6 | |

| At least a high school education | 85 | |

| No high school education | 15 | |

| Women | 44 | |

| Men | 56 | |

| White | 87 | |

| Non-White | 13 | |

| Perceived stress | 1.41 (0.02) | |

| Positive relationship quality | ||

| Confiding | 2.73 (0.02) | |

| Reliance | 2.84 (0.01) | |

| Negative relationship quality | ||

| Demanding | 1.49 (0.02) | |

| Criticism | 1.54 (0.02) | |

| Blood pressure | ||

| Systolic | 135.26 (0.52) | |

| Diastolic | 80.90 (0.33) | |

Note. Perceived stress rated from 1 (rarely or none of the time) to 4 (most of the time). Relationship quality rated from 1 (hardly ever [or never]) to 3 (often).

Measures

Blood pressure.

Blood pressure readings were taken with the Lifesource digital blood pressure monitor Model UA-767PVL, following guidelines adapted from the manufacturer’s instruction guide (Williams et al., 2009). Participants were seated with their feet flat on the floor and their left arm laid on a surface with the palm up. The cuff size was visually estimated and two blood pressure measurements were taken with a 1min pause between them. A third reading was taken if the first two readings were substantially different (systolic ≥ 20mm Hg/diastolic ≥ 14mm Hg; Williams et al., 2009). The blood pressure scores reflect the mean across the multiple blood pressure readings.

Relationship quality.

Participants rated the positive and negative qualities of their relationships with a spouse or romantic, intimate, or sexual partner. The positive quality items were: “How often can you open up to your spouse/partner if you need to talk about your worries?” and “How often can you rely on your spouse/partner for help if you have a problem?” The negative quality items were: “How often does your spouse/partner make too many demands on you?” and “How often does your spouse/partner criticize you?” Participant response options included: 1 (hardly ever [or never]), 2 (some of the time), or 3 (often). These items are from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) 2002 (module 6) questionnaire and have been used in subsequent waves of the HRS study. We considered whether to combine the positive and negative items into scales; however, the alphas were relatively low: 0.60 for positive and 0.59 for negative. In addition, previous studies have found that relationship quality items often behave differently when predicting health outcomes and have examined them separately (Birditt & Antonucci, 2008). Thus, we examined each item separately and refer to them as confiding, reliance, demands, and criticism.

Stress.

Participants completed a four-item perceived stress scale derived from Cohen, Karmarck, and Mermelstein’s (1983) global measure of perceived stress. The specific items included: “I was unable to control important things in my life,” “I felt difficulties were piling up so high that I could not overcome them,” “I felt confident about my ability to handle personal problems (reverse coded),” and “I felt that things were going my way (reverse coded).” Participant response options included 1 (rarely or none of the time), 2 (some of the time), 3 (occasionally), or 4 (most of the time); a mean was calculated to create a stress score (α = 0.63).

Covariates.

We included several covariates associated with relationship quality and health (Antonucci, 2001; House et al., 1988). Gender was coded as 1 (women) or 0 (men). Age was included as a continuous variable. Education was coded as 0 (less than high school) or 1 (high school or greater). Race was coded as 1 (non-White) or 0 (white). Because associations with blood pressure vary depending on whether individuals take antihypertension medicine (Qato, Schumm, Johnson, Mihai, & Lindau, 2009), we controlled for antihypertension medicine in the analyses of blood pressure. There is debate in the literature regarding the best methods for adjusting for medication use, and we conducted additional sensitivity analyses comparing some of the methods in the Results section. Individuals were coded as 1 if they were taking one or more of the following medications: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta-andrenergic blockers, diuretics, and calcium channel blockers (Qato et al., 2009).

Analysis strategy.

All data were weighted before conducting analyses in line with recommendations for analyzing the NSHAP data (O’Muircheartaigh, Eckman, & Smith, 2009). The weight takes into account the probability of selection and adjusts for nonresponse. In addition to the weight variable, we included variables to adjust for the multiple-stage sampling design.

We assessed main effect and moderating models with multiple regression analyses. Main effect models examining relationship quality included all quality items (confiding, reliance, demands, criticism) and stress as predictors. The moderating models included the interaction between stress and each of the quality variables as predictors. All models included gender, age, education, and race as covariates. All continuous variables were grand mean-centered and categorical variables were effect was coded (−1, 1) as suggested by Aiken and West (1991). Models were estimated separately to predict systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Significant interactions were explored by calculating the simple slopes (Aiken & West, 1991). Interactions were plotted in graphs with stress on the x-axis and blood pressure on the y-axis with relationship quality as the grouping variable (1 SD less than and 1 SD greater than the mean).

Results

The results are presented in three sections. First, spouse/partner relationship quality, stress, and blood pressure are described. Next, the main effects of spouse/partner relationship quality and perceived stress on blood pressure were examined. Finally, the moderating effects of spouse/partner relationship quality on the stress–blood pressure link were assessed.

Description of the Data

Overall, participants reported low levels of perceived stress (Table 1), as well as high levels of positive relationship quality and low levels of negative relationship quality with spouses/partners. A total of 43% of the participants had hypertension, which is defined as systolic greater than or equal to 140mm Hg or diastolic greater than or equal to 90mm Hg according to the American Heart Association guidelines.

Correlations among stress, spouse/partner relationship quality, and blood pressure were calculated. The two positive quality items were positively correlated (r = .43, p < .01), and the two negative quality items were positively correlated (r = .43, p < .01). The four relationship quality variables had low correlations with blood pressure ranging from −.003 to .03. Stress was positively correlated with negative quality (demands, r = .13, criticize, r = .12; p < .01) and negatively correlated with positive relationship quality (confide, r = −.16, rely, r = −.16; p < .01). Stress was not significantly associated with blood pressure.

What are the Main Effects of Spousal/Partner Relationship Quality (Positive and Negative) and Stress on Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure?

Models revealed that there were no main effects of spousal/partner relationship quality or stress on blood pressure (Table 2). This was inconsistent with our hypotheses that individuals who reported greater spouse/partner relationship quality and lower stress would have lower blood pressure.

Table 2.

Linear Regression Models Predicting Blood Pressure as a Function of Spousal/Partner Relationship Quality and Perceived Stress (N = 1,854)

| Systolic blood pressure | Diastolic blood pressure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercept | 137.25 | 0.85** | 137.24 | 0.84** | 81.06 | 0.56** | 81.01 | 0.55** |

| Stress | −1.71 | 1.35 | −1.45 | 1.40 | −0.02 | 0.61 | 0.09 | 0.66 |

| Confiding | −0.34 | 1.26 | −0.27 | 1.35 | 0.45 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.72 |

| Reliance | −1.75 | 1.23 | −2.45 | 1.21* | −0.80 | 0.78 | −1.31 | 0.88 |

| Demanding | 1.08 | 0.61 | 1.22 | 0.67 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.43 |

| Criticism | −1.28 | 0.83 | −1.41 | 0.82 | 0.03 | 0.49 | 0.01 | 0.49 |

| Stress × confiding | −3.86 | 1.63* | −2.85 | 0.98** | ||||

| Stress × reliance | 4.66 | 1.88* | 3.66 | 1.29** | ||||

| Stress × demanding | −3.04 | 1.17* | −0.19 | 0.69 | ||||

| Stress × criticism | 2.10 | 1.57 | 0.74 | 0.91 | ||||

| Female | −1.65 | 0.49** | −1.65 | 0.47** | 0.50 | 0.28 | 0.51 | 0.27 |

| Age | 0.33 | 0.05** | 0.33 | 0.05** | −0.30 | 0.03** | −0.30 | 0.03** |

| Education | 0.17 | 0.58 | 0.25 | 0.58 | −0.21 | 0.41 | -0.15 | 0.41 |

| Non-white | 2.10 | 0.72** | 2.06 | 0.72** | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.83 | 0.47 |

| Hypertension medicines | 0.72 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.51 | −0.66 | 0.32* | −0.68 | 0.31* |

| R 2 | 0.03 | ** | 0.04 | *** | 0.05 | ** | .06 | *** |

Note. *p < .05 and **p < .01.

Does Spousal/Partner Relationship Quality Moderate the Associations Between Perceived Stress and Blood Pressure?

Models revealed moderating effects of spousal relationship quality on the stress–blood pressure link.

Positive spousal quality.

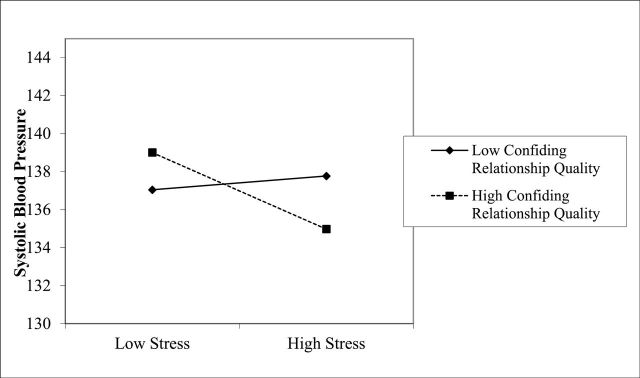

We found significant interactions between spousal/partner confiding and stress when predicting systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Table 2). Consistent with our hypothesis, the simple slope tests revealed that the association between stress and systolic blood pressure was negative among participants who reported higher levels of confiding (B = −3.53, p < .05; Figure 1). The association between stress and blood pressure was not significant among participants who reported lower levels of confiding. The simple slope tests for diastolic blood pressure were similar, but only approached significance. Overall, these findings indicate that the association between stress and blood pressure may be reduced among individuals with greater spousal confiding.

Figure 1.

Systolic blood pressure as a function of stress and confiding with spouse/partner.

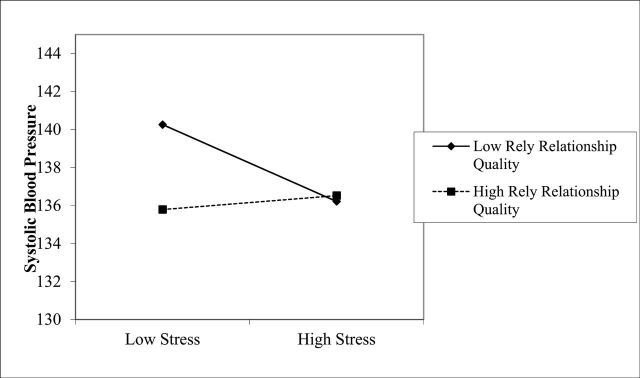

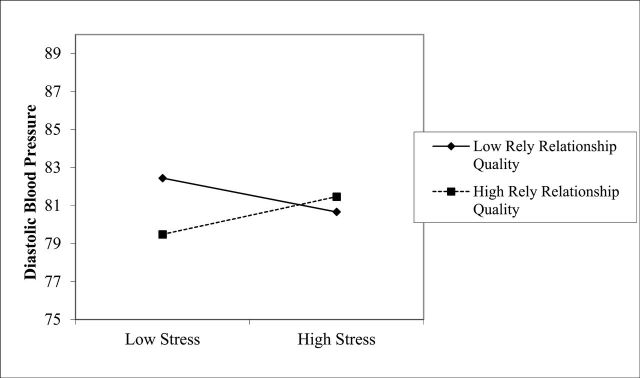

We also found significant interactions between relying on a spouse/partner and stress when predicting systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Table 2; Figures 2 and 3). Unexpectedly and inconsistent with our hypothesis, the association between stress and blood pressure was negative among individuals who reported lower relying on spouse/partner (systolic B = −3.54, p < .05; diastolic B = −1.56, p < .05). The slopes were not significant among people who reported greater reliance on spouse/partner. This finding indicates that relying less on spouse/partners moderates the stress–blood pressure link. Interestingly, relying less on a spouse/partner appeared to have negative effects on health when individuals were under low levels of stress but beneficial effects on health when individuals were under high levels of stress.

Figure 2.

Systolic blood pressure as a function of stress and reliance on spouse/partner.

Figure 3.

Diastolic blood pressure as a function of stress and reliance on spouse/partner.

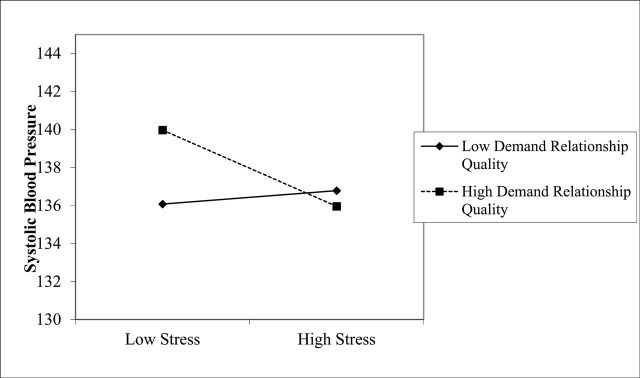

Negative spousal quality.

We found a significant interaction between spouse/partner demands and stress when predicting systolic blood pressure (Table 2; Figure 4). Unexpectedly, the association between stress and systolic blood pressure was negative among people who reported greater spouse/partner demands (B = −3.53, p < .05). In contrast, there was no association between stress and systolic blood pressure among people who reported lower spouse/partner demands. This finding indicates that the stress–blood pressure link is moderated by greater spousal/partner demands. It appears that high spousal/partner demands were associated with poorer health among individuals with lower stress but better health among individuals under higher stress.

Figure 4.

Systolic blood pressure as a function of stress and spousal/partner demands.

Post Hoc Analyses

The associations among stress, relationship quality, and blood pressure may vary depending on whether individuals are in more committed relationships or not (married/living with partner vs. romantic partners). Therefore, models were reestimated excluding individuals with romantic partners. All findings were the same with one exception. The stress by confiding interaction predicting systolic blood pressure became a trend, which may have been due to the decrease in power after removing romantic partners.

The associations may also vary depending on the duration of the relationship. Relationship duration information was available for individuals who were married or cohabitating; thus analyses were estimated controlling for relationship duration among the married and cohabitating individuals, and the same pattern of results emerged.

Because the spousal tie and links between the spousal tie and health often varies by gender (Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001), models were reestimated with all possible two-way and three-way interactions among relationship quality, stress, and gender. Although there were two significant three-way interactions when predicting diastolic blood pressure, one among gender, criticism, and stress and the other among gender, demands, and stress, the tests of the simple slopes were not significant.

We were concerned that participants may have varied in their overall physical health, which may account for some of the associations. Self-rated health is a particularly important determinant of well-being in the spousal relationship (Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, & Cartwright, 2009). Thus, all models were estimated again controlling for self-rated physical health, and the findings remained the same.

Finally, there is debate regarding whether to control for antihypertension medication when predicting blood pressure or to use other methods of adjustment (Tobin, Sheehan, Scurrah, & Burton, 2005). Analyses were conducted again without controlling for hypertension medicine, and the findings remained the same. Analyses were also conducted after adding a constant of 10 to systolic and a constant of 5 to diastolic blood pressure among individuals taking antihypertension medication as recommended in previous studies, and the same pattern of results emerged (Cui, Hopper, & Harrap, 2003; Tobin et al., 2005).

Discussion

Using data from the NSHAP, this study examined associations among spousal/partner relationship quality, stress, and blood pressure. Results support the moderating effect model which posits that in the context of stressful life events or circumstances, spousal/partner relationships are particularly influential by either preventing stress or reducing negative reactions to it. We found no evidence for the main effect model, which posits that a direct association between relationship quality and health exists irrespective of stress. The findings also showed that the effects of relationship quality are nuanced, with both negative and positive relationships having unique effects in the stress–health link. This study makes a distinctive contribution to the literature by examining the link between spousal/partner relationship quality and blood pressure in the presence of perceived stress among older individuals and providing insights into the mechanisms linking spousal/partner relations and health.

These results support the body of research that identifies biological pathways linking social relationships to health (Uchino et al., 1996). According to the biopsychosocial model of health, social and psychological factors influence overall health via biological pathways or mechanisms such as the cardiovascular system (Engel, 1977). In line with this model, this research examined the implications of social (spousal/partner quality) and psychological factors (stress) for the cardiovascular system (blood pressure) in order to further understand the spousal relationship–health link. The findings suggest that the cardiovascular system may be an important pathway by which relationships “get under the skin” to influence health.

Few studies conceptualize spousal/partner quality as a moderator between stress and health outcomes. For those that do, particularly those examining negative relationship qualities, the results have been mixed (Antonucci et al., 2010; Birditt & Antonucci, 2008). This study provides further understanding regarding the role of not only negative spousal/partner relationship quality in the association between stress and health, but also a more complex picture of the role of positive spousal/partner quality. Furthermore, this study revealed that marriage as well as cohabitation and romantic partners have important influences on health among older adults. Our focus on older adults is also novel, given that the majority of previous research has focused on younger couples. For older adults, chronic health problems are likely to be more prevalent, especially in the case of higher blood pressure and cardiovascular disease (Crimmins et al., 2005; Steptoe et al., 2003).

Positive Relationship Quality

The present findings concerning positive spousal/partner quality as a moderator between stress and health are only somewhat consistent with the sparse literature on this topic. The moderator model suggests that positive quality relationships buffer the influence of stress on health. However, we did not find links between stress and health, which is necessary for a buffering model (Cohen & Wills, 1985). This study showed that the association between stress and health does vary by positive quality ties but in expected and unexpected ways. Specifically, the negative association between stress and blood pressure for participants reporting higher levels of confiding with their spouse/partner corresponds with research concerning recovery from both work stress and congestive heart failure. That is, happily married women recovered from work-related stress more quickly than unhappily married women (Saxbe et al., 2008), and patients recovering from congestive heart failure who reported better quality relationships survived longer (Coyne et al., 2001). Thus, greater confiding in spouses appears to reduce the association between stress and blood pressure.

However, counter to our hypothesis, we found no association between stress and blood pressure for individuals reporting high reliance on their spouse, a finding which does not entirely support previous literature. In fact, the stress–health link was negative only among participants who reported lower spousal/partner reliance. Bookwala (2011) similarly found that greater spousal support exacerbated the link between poor vision and functional health. This finding is consistent with research concerning the dependence-support script and the independence-ignore script (Baltes, 1996), which holds that, for older individuals especially, dependent behaviors tend to elicit more attention; meanwhile, independent behaviors are essentially ignored. Particularly in long-term or close relationships, where behaviors tend to become ingrained, these scripts can lead to a loss of autonomy and control and may exacerbate any sense of helplessness and frustration in a stressful situation. Indeed, studies show that individuals may perceive support as over-protective or ineffective, which can be harmful to health (Hagedoorn et al., 2000). The findings also support the research indicating that individuals who receive support that they are not aware of (i.e., invisible support) have better well-being (Bolger, Kessler, & Zuckerman, 2000).

Due to the cross-sectional nature of the study design, however, it is possible that blood pressure influences relationship processes in the contexts of different stress levels. For example, individuals with lower blood pressure may rely less on spouses in times of stress because they feel less vulnerable and may have more diverse networks (with other ties to rely on) than individuals with higher blood pressure.

Negative Relationship Quality

Interestingly, greater negative relationship quality moderated the stress–health link but not in a way that was consistent with the exacerbation model. Inconsistent with our hypothesis, greater spousal demands appeared to reduce the link between stress and blood pressure. Similarly, Birditt and Antonucci (2008) found that individuals with life-threatening illnesses survived longer when they reported greater negative spousal quality (high demands or criticism). Spousal/partner demands may be necessary or helpful (e.g., demands to comply with a medical regimen or to think deeply about a stressful situation). Likewise, spousal demands may involve demands for support, which may be beneficial for health. Providing support to spouses is associated with better health than receiving support (Brown, Nesse, Vinokur, & Smith, 2003). In contrast, spouses with higher blood pressure who are under greater stress may receive greater spousal demands (e.g., to exercise or take medication). Because of the cross-sectional nature of the study design, we are unable to determine the specific direction of effects.

Limitations and Future Directions

As with most studies, the present research has limitations. Although rich, these data are cross-sectional and as such cannot identify directional links. Future research would benefit from follow-up studies with these particular participants (or other longitudinal studies) in order to examine bidirectional links among spouse/partner relationship quality, perceived stress, and blood pressure over time. Measurement of all constructs of interest—marital quality, stress, and blood pressure—could no doubt have been more thorough, a situation common to survey research. As an example, only four items assessed relationship quality; we lack information regarding the relationship processes that underlie the reports of relationship quality. For instance, do spousal or partner demands include those involving health behaviors? We need to include more extensive measures of spousal/partner quality in future studies (e.g., conflict, coping strategies, and satisfaction with support). Further, the measurement of blood pressure did not include controls such as a specified rest time prior to measurement or prohibition of caffeinated beverages, which are often included in more controlled laboratory or clinical settings.

Moreover, this study did not examine the influence of other potentially important relationships, such as relationships with children, grandchildren, extended family, and friends. These types of relationships, beyond the spouse/partner relationship, are important to assess as they can provide important resources in times of stress, and thus shed light on the broader social milieu in which the stress–health link resides.

This study highlights the often complicated nature of spouse/partner relationship quality, stress, and their associations with biological pathways. Stress appears to be less detrimental for health when individuals perceive their spousal/partner tie as emotionally supportive, less reliable, and more demanding. These findings emphasize the importance of examining the influence of multiple dimensions of spousal/partner relationship quality on the health processes of older adults.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging (AG029879 to K.S.B.).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lindsay Ryan and Kristine Ajrouch for their helpful comments on earlier drafts, Angela Turkelson for her help with statistical analyses, and Phil Schumm for additional details regarding the study design and data.

References

- Aiken L. S., West S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C. (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support, and sense of control. In Birren J. E., Schaie K. W. (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (5th ed., pp. 427–453). San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci T. C., Birditt K. S., Webster N. J. (2010). Social relations and mortality: A more nuanced approach. Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 649–659 doi:10.1177/1359105310368189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August K. J., Rook K. S., Newsom J. T. (2007). The joint effects of life stress and negative social exchanges on emotional distress. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, S304–S314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes M. M. (1996). Patterns of communication in old age: The dependence-support and independence-ignore script. Health Communication, 8, 217–231 doi:10.1207/s15327027hc0803_3 [Google Scholar]

- Birditt K., Antonucci T. C. (2008). Life sustaining irritations? Relationship quality and mortality in the context of chronic illness. Social Science & Medicine, 67, 1291–1299 doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N., Zuckerman A., Kessler R. C. (2000). Invisible support and adjustment to stress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 953–961 doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J. (2005). The role of marital quality in physical health during the mature years. Journal of Aging and Health, 17, 85–104 doi:10.1177/0898264304272794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J. (2011). Marital quality as a moderator of the effects of poor vision on quality of life among older adults. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 605–616. 10.1093/geronb/gbr091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. L., Lin I. F. (2012). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990-2010. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 731–741 doi:10.1093/geronb/gbs089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. L., Nesse R. M., Vinokur A. D., Smith D. M. (2003). Providing social support may be more beneficial than receiving it: results from a prospective study of mortality. Psychological Science, 14, 320–327. 10.1111/1467-9280.14461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevan A. (1996). As cheaply as one: Cohabitation in the older population. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58, 656–667 doi:10.2307/353726 [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. (2004). Social relationships and health. The American Psychologist, 59, 676–684. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396 doi:10.2307/2136404 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Wills T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357 doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne J. C., Rohrbaugh M. J., Shoham V., Sonnega J. S., Nicklas J. M., Cranford J. A. (2001). Prognostic importance of marital quality for survival of congestive heart failure. The American Journal of Cardiology, 88, 526–529 doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(01)01731-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins E. M., Seeman T. (2000). Integrating biology into demographic research on health and aging (with a focus on the MacArthur Study of Successful Aging). In Finch C. E., Vaupel J. W., Kinsella K. (Eds.), Cells and surveys: Should biological measures be included in social science research?, (pp. 9–41). Washington, DC: National Academy Press; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins E. M., Alley D., Reynolds S. L., Johnston M., Karlamangla A., Seeman T. (2005). Changes in biological markers of health: older Americans in the 1990s. Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 60, 1409–1413 doi:10.1093/gerona/60.11.1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J. S., Hopper J. L., Harrap S. B. (2003). Antihypertensive treatments obscure familial contributions to blood pressure variation. Hypertension, 41, 207–210 10.1161/01.HYP.0000044938. 94050.E3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado J., Jacobs E. A., Lackland D. T., Evans D. A., Mendes de Leon C. F. (2012). Differences in blood pressure control in a large population-based sample of older african americans and non-Hispanic whites. Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 67, 1–6 doi:10.1093/gerona/gls106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science (New York, N.Y.), 196, 129–136 doi:10.1126/science.847460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner J., Oswald A. (2004). How is mortality affected by money, marriage, and stress? Journal of Health Economics, 23, 1181–1207 doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin J. S. (2003). Embracing complexity: A consideration of hypertension in the very old. Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 58, 653–658 doi:10.1093/gerona/58.7.M653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn M., Kuijer R. G., Buunk B. P., DeJong G. M., Wobbes T., & Sanderman R. (2000). Marital satisfaction in patients with cancer: Does support from intimate partners benefit those who need it most? Health Psychology, 19, 274–282. 10.1037// 0278-6133.19.3.274 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L. C., Masi C. M., Berry J. D., Cacioppo J. T. (2006). Loneliness is a unique predictor of age-related differences in systolic blood pressure. Psychology and Aging, 21, 152–164 doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helson R., Kwan V. S. Y. (2000). Personality development in adulthood: The broad picture and processes in one longitudinal sample. In Hampson S. E. (Ed.), Advances in personality psychology, Vol. 1, New York: Psychology Press [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann C., Smith J. (2007). Life-history related differences in possible selves in very old age. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 64, 109–127 doi:10.2190/GL71-PW45-Q481-5LN7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Birmingham W., Jones B. Q. (2008). Is there something unique about marriage? The relative impact of marital status, relationship quality, and network social support on ambulatory blood pressure and mental health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 35, 239–244 doi:10.1007/s12160-008-9018-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J. S., Landis K. R., Umberson D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241, 540–545 doi:10.1126/science.3399889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyck M. H. (2001). Romantic relationships in later life. Generations, 25, 9–18 [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser J. K., Newton T. L. (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 472–503 doi:10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz D. S., Falconer J. J. (1995). Measurement of cardiovascular responses. In Cohen S., Kessler R. C., Gordon L. (Eds.), Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists, (pp. 193–212). New York: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Krause N., Goldenhar L., Liang J., Jay G., Maeda D. (1993). Stress and exercise among the Japanese elderly. Social Science & Medicine, 36, 1429–1441 doi:10.1016/0277-9536(93)90385-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau S. T., Laumann E. O., Levinson W., Waite L. J. (2003). Synthesis of scientific disciplines in pursuit of health: The Interactive Biopsychosocial Model. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 46, S74–S86 doi:10.1353/pbm.2003.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz F. O., Wickrama K. A., Conger R. D., Elder G. H. Jr. (2006). The short-term and decade-long effects of divorce on women’s midlife health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 111–125 doi:10.1177/002214650604700202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loucks E. B., Sullivan L. M., D’Agostino R. B., Sr, Larson M. G., Berkman L. F., Benjamin E. J. (2006). Social networks and inflammatory markers in the Framingham Heart Study. Journal of Biosocial Science, 38, 835–842 doi:10.1017/S0021932005001203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoli L., Villari P., M Pirone G., Boccia A. (2007). Marital status and mortality in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 64, 77–94 doi:10.1016/j.socscimed. 2006.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalie J. H., Goldbourt U. (1976). Unrecognized myocardial infarction: five-year incidence, mortality, and risk factors. Annals of Internal Medicine, 84, 526–531 10.1059/0003-4819-84-5-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Muircheartaigh C., Eckman S., Smith S. (2009). Statistical design and estimation for the national social life, health, and aging project. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64, i12–i19 doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza J. R., Almeida D. M., Dmitrieva N. O., Klein L. C. (2010). Frontiers in the use of biomarkers of health in research on stress and aging. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 65, 513–525 doi:10.1093/geronb/gbq049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno R., Wilson-Genderson M., Cartwright F. (2009). Self-rated health and depressive symptoms in patients with end-stage renal disease and their spouses: A longitudinal dyadic analysis of late-life marriages. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 64, 212–221 doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qato D. M., Schumm L. P., Johnson M., Mihai A., Lindau S. T. (2009). Medication data collection and coding in a home-based survey of older adults. Journals of Gerontology. Social Sciences, 64, i86–i93 doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles T. F., Kiecolt-Glaser J. K. (2003). The physiology of marriage: Pathways to health. Physiology & Behavior, 79, 409–416 doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00160-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxbe D. E., Repetti R. L., Nishina A. (2008). Marital satisfaction, recovery from work, and diurnal cortisol among men and women. Health Psychology, 27, 15–25 doi:10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T. E. (1996). Social ties and health: the benefits of social integration. Annals of epidemiology, 6, 442–451 doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(96)00095-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T. E. (2003). Integrating psychosocial factors with biology: The role of protective factors in trajectories of health and aging. In Kessel F., Rosenfield P. L., Anderson N. B. (Eds.), Expanding the boundaries of health and social science: Case studies in interdisciplinary innovation, (pp. 206–227). New York: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Slatcher R. B. (2010). Marital functioning and physical health: Impli cations for social and personality psychology Social and Person ality Psycho logy Compass, 4, 455–469 doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00273.x [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A., Kunz-Ebrecht S., Owen N., Feldman P. J., Willemsen G., Kirschbaum C., Marmot M. (2003). Socioeconomic status and stress-related biological responses over the working day Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 461–470 doi:10.1097/01.PSY. 0000035717.78650.A1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin M. D., Sheehan N. A., Scurrah K. J., Burton P. R. (2005). Adjusting for treatment effects in studies of quantitative traits: Antihypertensive therapy and systolic blood pressure. Statistics in Medicine, 24, 2911–2935 10.1002/sim.2165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B. N. (2004). Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B. N. (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 236–255 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B. N., Birmingham W., Berg C. A. (2010). Are older adults less or more physiologically reactive? A meta-analysis of age-related differences in cardiovascular reactivity to laboratory tasks. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 65B, 154–162 doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino B. N., Cacioppo J. T., Kiecolt-Glaser J. K. (1996). The relationship between social support and physiological processes: A review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 488–531 doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2010). Table 57. Marital Status of the Population by Sex and Age Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0058.pdf

- Waite L. J., Gallagher M. (2000). The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially, New York: Doubleday [Google Scholar]

- Waite L. J., Laumann E. O., Levinson W., Lindau S. T., McClintock M. K., O’Muircheartaigh C. A., Schumm P. L. (2010). National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) [Computer file]. ICPSR20541-v5, Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; [distributor], 2010-07-28. doi:10.3886/ICPSR20541 [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. X., Leineweber C., Kirkeeide R., Svane B., Schenck-Gustafsson K., Theorell T., Orth-Gomér K. (2007). Psychosocial stress and atherosclerosis: Family and work stress accelerate progression of coronary disease in women. The Stockholm Female Coronary Angiography Study. Journal of Internal Medicine, 261, 245–254 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01759.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. R., Pham-Kanter G., Leitsch S. A. (2009). Measures of chronic conditions and diseases associated with aging in the national social life, health, and aging project. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 64, i67–i75 doi:10.1093/geronb/gbn015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]