Abstract

Objective

The Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) graft (Hemosphere/CryoLife Inc, Eden Prairie, Minn) has provided an innovative means to obtain hemodialysis access for patients with severe central venous occlusive disease. The outcomes of this novel treatment modality in a difficult population have yet to be clearly established.

Methods

A retrospective review of HeRO graft placement from June 2010 to January 2012 was performed. Patient hemodialysis access history, clinical complexity, complications, and outcomes were analyzed. Categoric data were described with counts and proportions, and continuous data with means, ranges and, when appropriate, standard deviations. Patency rates were analyzed using life-table analysis, and patency rate comparisons were made with a two-group proportion comparison calculator.

Results

HeRO graft placement was attempted 21 times in 19 patients (52% women), with 18 of 21 (86%) placed successfully. All but one was placed in the upper extremity. Mean follow-up after successful placement has been 7 months (range, 0–23 months). The primary indication for all HeRO graft placements except one was central vein occlusion(s) and need for arteriovenous access. Patients averaged 2.0 previous (failed) accesses and multiple catheters. Four HeRO grafts (24%), all in women, required ligation and removal for severe steal symptoms in the immediate postoperative period (P < .01 vs men). Three HeROs were placed above fistulas for rescue. All thrombosed <4 months, although the fistulas remained open. An infection rate of 0.5 bacteremic events per 1000 HeRO-days was observed. At a mean follow-up of 7 months, primary patency was 28% and secondary patency was 44%. The observed 12-month primary and secondary patency rates were 11% and 32%, respectively. Secondary patency was maintained in four patients for a mean duration of 10 months (range, 6–18 months), with an average of 4.0 ± 2.2 thrombectomies per catheter.

Conclusions

HeRO graft placement, when used as a last-resort measure, has been able to provide upper extremity access in patients who otherwise would not have this option. There is a high complication rate, however, including a very high incidence of steal in women. HeRO grafts should continue to be used as a last resort.

The lifespan of arteriovenous access (AVA) remains finite. In increasing numbers, hemodialysis patients outlive their upper extremity access options due to outflow venous stenosis and are faced with less desirable alternatives that include leg arteriovenous grafts (AVG), tunneled dialysis catheters (TDC), and other imaginative routes of access. Incidence rates for central venous occlusive disease before the Fistula First initiative have been reported as high as 50% in dialysis patients.1 Since the Fistula First initiative, arteriovenous fistula (AVF) creation rates have increased, but so has catheter use.2 With 80% of patients in 2010 initiating hemodialysis with a catheter3 and the frequent use of central catheters for bridging therapy, it is no surprise that central venous occlusive disease poses a significant obstacle in this population.

A new option for upper extremity AVA in the face of venous occlusion and stenosis was established in 2008 when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) device (Hemosphere, a CryoLife Inc company, Eden Prairie, Minn), a novel means to establish access in dialysis patients with severe central venous disease. The HeRO may be used to create new access, “rescue” a failing access, and has also been used to address symptoms associated with severe upper extremity venous hypertension.4–6 Studies thus far have demonstrated superior patency rates and decreased infection and intervention rates compared with TDCs. Patency rates have been reported to rival AVGs.7–9 Overall, the literature related to the HeRO device thus far, although meager, has been overwhelmingly positive. Unfortunately, the experience at our institution did not appear to mirror these reports and prompted our review.

Our study objectives were to review our institution’s data on consecutive HeRO patients with a focus on access history, vascular anatomy, interventions, patency, and complications. Our aim was to provide additional real world, non–industry-sponsored data on the HeRO device.

METHODS

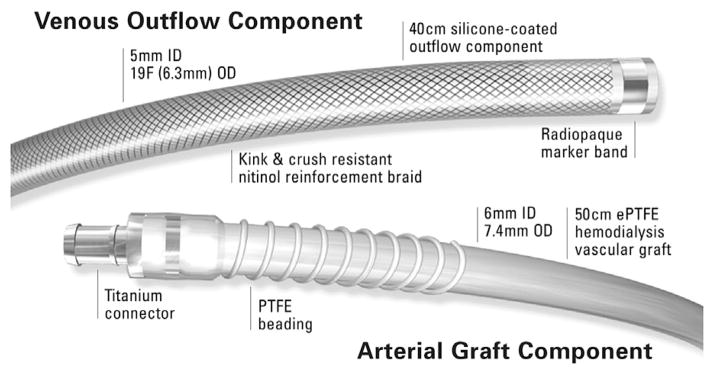

This study was a single-institution, retrospective review of 19 patients who underwent 21 consecutive attempts at HeRO implantation between June 2010 and January 2012. The HeRO graft consists of two primary components (Fig 1): the venous outflow component consists of a single-lumen, nitinol braid-reinforced, silicone-coated catheter with an inner diameter of 5 mm, and the arterial inflow component consists of a standard 6-mm expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) graft (W. L. Gore & Associates, Newark, Del).

Fig 1.

Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) device components. ePTFE, Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene; ID, internal diameter; OD, outer diameter. (Used with permission of CryoLife, Inc.)

The silicon portion is placed through the occluded or stenotic subclavian, internal jugular, or collateral veins to the level of the cavoatrial junction. In our cohort, all but one patient underwent placement of the venous end of the HeRO at the cavoatrial junction according to bony landmarks and completion venogram. The opposite end is tunneled to the deltopectoral groove, where it is connected to the ePTFE portion. This is sewn into the brachial artery in the same fashion as a standard upper arm AVA. The graft can also be placed in the femoral location.

Two surgeons, whose practices include a large proportion of hemodialysis access work, performed all procedures. At our institution, the HeRO graft is reserved for patients with no standard upper extremity access options due to central venous disease. This includes patients with bilateral central venous occlusions and patients with unilateral venous occlusions and severe contralateral arterial disease. All HeRO candidates undergo arterial and venous duplex examinations, in addition to central venograms, before HeRO attempt. Patients with options of a leg graft vs HeRO are evaluated on an individual basis depending on body habitus, arterial supply, and personal preferences. HeRO grafts were placed in patients with long-segment venous occlusions where balloon angioplasty or stenting was not appropriate.

After obtaining institutional IRB approval, we collected data on patient demographics, comorbidities, and anatomic and procedural details that included reinterventions and complications. Categoric data are described with counts and proportions, and continuous data with means, ranges, and standard deviations. Patency rates were analyzed using life-table analysis, and patency rate comparisons were made with a two-group proportion comparison calculator. Both were performed using Stata 12 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, Tex).

RESULTS

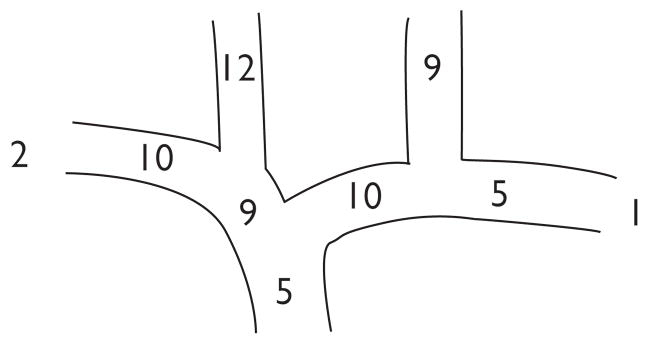

HeRO placement was attempted 21 times in 19 patients. Demographics and comorbidities are described in Table I. Most patients had diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and were morbidly obese, and four patients had a hypercoagulable condition. The distribution of total venous occlusions is summarized in Fig 2. Specifically, three-fourths of the patients had superior vena cava (SVC) or bilateral central venous occlusions. Three of the remaining five patients had unilateral occlusions with contralateral arterial disease; one was performed for AVF salvage in the setting of ipsilateral central occlusion; and one had no central occlusions, but all veins were diminutive and compounded by the patient’s morbid obesity.

Table I.

Patient demographics and comorbidities

| Variable | Mean (range) or No. (%) (n = 19) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, years | 54.8 (18–80) |

| Female | 10 (53) |

| White | 8 (42) |

| Black | 11 (58) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 10 (53) |

| Hypertension | 17 (89) |

| Tobacco use | 12 (63) |

| Prior renal transplant | 10 (53) |

| Prior peritoneal dialysis | 4 (21) |

| Morbid obesity | 10 (53) |

| Hypercoagulable | 4 (21) |

Fig 2.

Distribution of total venous occlusions (patients could have more than one occlusion).

Although access histories were incomplete, a mean number of 2.8 ± 1.6 previous TDCs and 2.0 ± 2.1 dialysis accesses were documented. At the time of HeRO attempt, 95% of patients had central access, with 19 using TDCs (eight femoral, six internal jugular, and five subclavian), one had a failed upper extremity HeRO, and the last had a failing leg AVG. Three of the 21 procedures were for AVF salvage, with fistula anastomoses performed in an end-to-side fashion. All procedures but one were for upper extremity access. Nine placements were performed using TDCs or previous HeRO grafts to gain central access. TDC was used for bridging therapy in all successful HeRO attempts, with the HeRO typically cleared for use 2 weeks after placement.

Technical success was achieved in 86% of the 21 HeRO implant attempts. The three failures did not have upper extremity central catheter access available at the time of the attempt (two had leg TDCs and one had a leg AVG), and the occluded upper extremity central veins could not be traversed. Of those with successful placement, 38% developed 30-day postoperative complications that included steal syndrome (n = 4), arm hematoma related to HeRO explant (n = 1), leg AVG blowout after unsuccessful HeRO attempt (n = 1), and death (n = 2). The deaths occurred at 2 weeks and 30 days, and both were of unclear etiology, with the patients found dead at home from no obvious cause. Families did not seek autopsies in either patient. The patients had uneventful dialysis sessions within days of dying, and the dialysis staff had not noted obvious problems.

Of the 18 successful implantations, most were performed through the internal jugular vein, and laterality was almost evenly split (Table II). Most inflow was gained from the brachial artery, but three were from an AVF and one was from the superficial femoral artery. Venous outflow was through the SVC in 89%, which often required navigation of venous collaterals to reach. The leg HeRO drained through the inferior vena cava after navigation of occluded iliac veins, and only one upper extremity device was unable to be placed at the cavoatrial junction. The HeRO tip for this device was left in the contralateral subclavian vein because the occluded SVC could not be navigated and the right subclavian vein demonstrated adequate collateral flow back to the heart. This patient had right arm axillary venous occlusion and severe right arm arterial disease.

Table II.

Venous access details

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Successful implantation | 18 |

| By TDC or prior HeRO | 9 (50) |

| Insertion site | |

| Internal jugular vein | 11 (61) |

| Right | 7 (39) |

| Left | 4 (22) |

| Subclavian vein | 6 (34) |

| Right | 1 (6) |

| Left | 5 (28) |

| External iliac vein | 1 (6) |

| Left | 1 (6) |

HeRO, Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow; TDC, tunneled dialysis catheter.

The three patients with unsuccessful HeRO attempts went on to have leg AVGs. Two were young muscular men, and one was a young woman. Both men had blow-outs of their grafts in the immediate postoperative period and were successfully resuscitated, but both the grafts were removed. The remaining patient had a functional leg AVG until her renal transplant 10 months later.

Four women had steal syndrome that mandated removal of the HeRO graft in the immediate postoperative period. All patients had at least a faintly palpable radial pulse preoperatively. All had evidence of significant arterial disease, with one patient having had a previous below-knee amputation; one had a completely occluded contralateral brachial artery, one had required coronary revascularization before age 40, and the last had an extensive arterial and venous occlusive history. Three patients had severe pain and motor dysfunction in the dominant arm in the postoperative recovery area and desired immediate graft removal rather than revision. The remaining patient underwent HeRO banding and brachial and ulnar artery angioplasty in attempts to treat the symptoms of finger numbness, but without success. Her graft was removed on postoperative day 8.

The cohort provided 3896 HeRO-days for analysis. Approximately three reinterventions were required per HeRO-year to maintain patency. Two HeRO-related bacteremia events occurred, one at 4 months and the other at 7 months, and both required explantation. This resulted in an infection rate of 0.5 bacteremic events per 1000 HeRO-days (Table III details reintervention and infection rate comparisons with other studies).

Table III.

Reintervention, infection, and patency rates by study group

| First author | No. | Reinterventions per year | Infections per 1000 HeRO-days | Primary patency, %

|

Secondary patency, %

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-month | 8.6-month | 12-month | 6-month | 8.6-month | 12-month | ||||

| This study | 21 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 39 | 11 | 60 | 32 | ||

| Gage8 | 164 | 1.5 | 0.14 | 60.0 | 48.8 | 90.8 | 90.8 | ||

| Steerman12 | 62 | 6.2 | NA | 26.0 | 61.0 | ||||

| Katzman7,a | 36 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 38.9 | 72.2 | ||||

HeRO, Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow; NA, not available.

Patency rates reported for mean follow-up period of 8.6 months.

Perioperative anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy consisted of aspirin (33%), clopidogrel (17%), and warfarin (44%). Seven HeRO attempts had no anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy postoperatively.

HeRO primary graft patency was 28% and secondary patency was 44% at a mean follow-up of 7 months (range, 0–23 months). Life-table analysis (Table IV) demonstrated primary and secondary patency rates of 39% and 60%, respectively, at 6 months. At 12 months, the primary patency rate was 11% and the secondary patency rate was 32%. There were no patients with primary-assisted patency. Secondary patency was maintained in four patients for a mean duration of 10 months (range, 6–18 months), with an average of 4.0 ± 2.2 thrombectomies per graft. Table III reports the patency rates at 6 and 12 months compared with other HeRO study groups.

Table IV.

Life-table analysis of primary and secondary patency for 18 patients with successful Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) graft placement

| Outcome | Interval, months | At risk at beginning of interval, No. | Failed during interval, No. | Withdrawn during interval, No. | Interval failure rate | Cumulative patency, % | SE, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary patency | 0 to 1 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 0.23 | 77 | 10 |

| 1 to 2 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 0.16 | 65 | 12 | |

| 2 to 3 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0.20 | 52 | 12 | |

| 3 to 4 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0.13 | 45 | 12 | |

| 4 to 5 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0.14 | 39 | 12 | |

| 5 to 6 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 39 | 12 | |

| 7 to 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0.20 | 31 | 12 | |

| 9 to 10 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.29 | 22 | 11 | |

| 11 to 12 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.50 | 11 | 10 | |

| 16 to 17 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 11 | 10 | |

| Secondary patency | 0 to 1 | 18 | 5 | 0 | 0.28 | 72 | 11 |

| 1 to 2 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 0.08 | 66 | 11 | |

| 3 to 4 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0.09 | 60 | 12 | |

| 5 to 6 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 60 | 12 | |

| 6 to 7 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0.11 | 54 | 12 | |

| 7 to 8 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0.13 | 47 | 12 | |

| 8 to 9 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0.14 | 40 | 12 | |

| 9 to 10 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 40 | 12 | |

| 11 to 12 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0.20 | 32 | 12 | |

| 13 to 14 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 32 | 12 | |

| 16 to 17 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0.00 | 32 | 12 | |

| 22 to 23 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.00 | 32 | 12 |

SE, Standard error.

The three HeRO devices placed for AVF salvage thrombosed ≤4 months of placement, although the AVFs distal to them stayed open. Two of these AVFs continue to be used because the arm swelling that initiated HeRO placement resolved. In the remaining HeRO patient for AVF salvage, a new HeRO graft was placed within the same arm as the unusable fistula. This has been used without incident.

DISCUSSION

At our institution, HeRO candidates are truly end-stage dialysis patients with their extensive medical histories and complicated access pasts. We have found that many patients referred for the HeRO graft do not need one after a thorough work-up with venous duplex, with or without central venogram, demonstrating patent central veins. Those who are appropriate HeRO candidates have often failed multiple previous access attempts, have concomitant arterial disease, and represent an extremely challenging patient cohort. In addition, our practice is to aggressively treat central venous occlusions rather than place HeRO grafts. HeROs were only placed in patients with very long occlusions of the subclavian vein, in combination with internal jugular occlusions, when internal jugular turndown was not appropriate, or when the SVC was occluded or had a long-segment stenosis. The one exception in our cohort was a patient with very small central veins and a long history of access thrombosis with no other demonstrable reason for thrombosis.

The spectrum of comorbidities in our patients was quite similar to previous published HeRO studies but was most notable for a fairly high proportion of patients with a hypercoagulable condition (21%). We defined hyper-coagulable condition as a clinical diagnosis of a hyper-coagulable state confirmed by laboratory testing or hematologic consultation or a history of multiple access thromboses without obvious cause and subsequent long-term anticoagulation for this. Although the latter group may have undergone the hypercoagulable work-up without establishment of an official diagnosis, we believe the strong tendency for their access to thrombose places them in a similar high-risk category.

Despite a relatively high successful placement rate of 86%, one-third of all attempts resulted in immediate failure, documented as three unsuccessful placements and four steal syndromes that required immediate ligation and removal. The access history of each immediate failure after HeRO attempt culminated in 4 renal transplants, 2 leg AVGs, 1 leg HeRO, and 1 leg TDC, which further reiterates the advanced end-stage status of this cohort. The three HeRO placements for AVF salvage, placed for severe arm swelling, thrombosed ≤4 months of placement. The AVFs remained patent, however, due to the use of an end-to-side anastomosis. Of the five reported cases of HeRO use for AVF salvage, two were anastomosed in an end-to-side fashion,4 two in an end-to-end fashion,5,6 and one was not described.6 The end-to-end HeROs remained patent at 64 and 21 months,6 and the end-to-side HeROs remained patent at 5 and 14 months. We adopted the end-to-side technique because we did not want to sacrifice the patients’ functioning AVF in the attempt to reduce venous hypertension symptoms.

Two areas of complications deserve additional description. First, the 22% incidence of steal syndrome has not previously been described other than as a hypothetical risk, with only a few reported instances in all the literature: 1 of 38 (2.6%),7 2 of 164 (1.4%),8 and 1 of 65 (1.5%).10 Although each of our patients with steal had inflow vessels >3 mm and palpable radial pulses preoperatively, they all had significant smoking histories and various degrees of peripheral arterial disease—one had required a below-knee amputation and another had contralateral brachial artery occlusion. Three of the four had diabetes and three had previous renal transplantations. We believe that these comorbidities, compounded by the female propensity to have smaller distal vessels, contributed to our high rate of steal syndrome and truly reflects the end-stage nature of these patients. However, the relatively large 6-mm ePTFE graft, despite being anastomosed at approximately 90° to the artery to minimize the anastomotic area, may have also added to the risk. Additional attempts at banding or otherwise restricting the flow were not attempted due to the high likelihood of graft thrombosis11 combined with the immediate and severe nature of patient symptoms.

Two HeRO-related bacteremia events occurred, one at 4 months and the other at 7 months, and both grafts required explantation. This resulted in an infection rate of 0.5 bacteremic events per 1000 catheter-days. Our infection rate of 0.5 per 1000 HeRO-days is well below the TDC rate of 2.3 per 1000 catheter-days calculated by Katzman et al.7 Both infections in our cohort occurred months after removal of the bridging TDC. We had no perioperative contamination, which may be due to our practice of central cutdown onto a TDC at the time of HeRO placement if this is used as a portal to the cavoatrial junction.

Finally, in comparing our results with three currently available studies,7,8,12 two peer-reviewed, we see a midlevel reintervention rate and a comparable infection rate (Table III). Our initial patency rates are comparable to those reported at 6 months (Gage et al8) and 8.6 months (Katzman et al7), but 6-month secondary patency was significantly less than the 90.8% reported by Gage et al.8 At 12 months, our primary and secondary patency rates, 10% and 37%, respectively, were significantly lower than the other studies (Table III), except for the 26% primary patency reported by Steerman et al.12

Leg AVGs are generally available as an alternative to HeRO grafts, and a recent presentation demonstrated that these have better patency and lower intervention rates compared with HeRO grafts, although a limitation of that data set is a very large HeRO intervention rate that resulted in a lower but still high intervention rate in leg grafts.12 Leg grafts are not without complications, and this can be seen in our own data. Arterial disease and obesity also complicate leg graft placements. Despite these considerations, our data indicate that HeRO grafts have poor results and that leg grafts could be a better choice for those patients who could have either. Unfortunately, some patients are not able to have an upper extremity HeRO or a leg graft, and these patients have permanent groin catheters, putting in jeopardy the iliac veins needed as outflow for renal transplantation.

Reasons for our poor patency rates other than primary placement failure have been investigated, with AVF salvage anastomosis technique and steal syndrome etiologies explored above. We found that HeRO graft failures have been for graft stenosis or did not have an obvious etiology, except the thrombosis occurred when the patient’s international normalized ratio was subtherapeutic. No instances of venous stenosis or thrombosis at the HeRO tip have been reported. With regard to operator experience, two surgeons whose practices consist of a large proportion of dialysis access creation in difficult dialysis patients placed all HeRO devices. The low rate of periprocedural antiplatelet therapy could have been a contributor, based on the findings of Day et al.13 In their study, device thrombosis was less likely in patients treated with clopidogrel. We have since adjusted our practice to include clopidogrel with a preoperative loading dose, followed by continuation through the life of the HeRO device, and we will closely monitor whether this makes a difference.

The obvious weakness of this study is the small sample size and its retrospective nature. Although these limitations certainly confine the ability to generalize our findings, the addition of our results to the current body of HeRO literature provides balance with additional real-world outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

On the basis of our institution’s experience with the HeRO device thus far, we believe that patients truly appropriate for a HeRO are complicated, high-risk patients when it comes to AVA. In this particular patient group, the HeRO device demonstrated high complication rates, poor patency, and required many reinterventions. Steal syndrome, which we found occurred more frequently than previously reported, appears to be a real risk, especially in women. We acknowledge that HeROs can work and when they do, they can work well, but we believe the HeRO graft should be reserved for those who fail all other traditional AVF and graft options and should be offered as an alternative to the leg AVG.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

Presented in oral form at the Twenty-sixth Annual Meeting of the Eastern Vascular Society, Pittsburgh, Pa, September 13–15, 2012.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: ED, RC

Analysis and interpretation: ED, JW

Data collection: JW

Writing the article: JW, ED

Critical revision of the article: ED, RC

Final approval of the article: ED, RC, JW

Statistical analysis: JW, ED

Obtained funding: Not applicable

Overall responsibility: ED

References

- 1.Kundu S. Central venous disease in hemodialysis patients: prevalence, etiology and treatment. J Vasc Access. 2010;11:1–7. doi: 10.1177/112972981001100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allon M, Lok CE. Dialysis fistula or graft: the role for randomized clinical trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2348–54. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06050710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2011 annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allan BJ, Prescott AT, Tabbara M, Bornak A, Goldstein LJ. Modified use of the Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) graft for salvage of threatened dialysis access. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:1127–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen GJ, Anaya-Ayala JE, Ismail N, Smolock CJ, Davies MG, Peden EK. Successful use of the HeRO device to salvage a functional arteriovenous fistula and resolve symptoms of venous hypertension. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011:e37–39. Extra. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gage SM, Ahluwalia HS, Lawson JH. Salvaging vascular access and treatment of severe limb edema: case reports on the novel use of the hemodialysis reliable outflow vascular access device. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25(387):e381–5. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katzman HE, McLafferty RB, Ross JR, Glickman MH, Peden EK, Lawson JH. Initial experience and outcome of a new hemodialysis access device for catheter-dependent patients. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:600–7. 607, e601. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gage SM, Katzman HE, Ross JR, Hohmann SE, Sharpe CA, Butterly DW, et al. Multi-center experience of 164 consecutive Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow [HeRO] graft implants for hemodialysis treatment. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44:93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nassar GM. Long-term performance of the hemodialysis reliable outflow (HeRO) device: the 56-month follow-up of the first clinical trial patient. Semin Dial. 2010;23:229–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2010.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fusselman M. Results of a customer-based, post-market surveillance survey of the HeRO access device. Nephrol News Issues. 2010;24:30–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta N, Yuo TH, Konig G, 4th, Dillavou E, Leers SA, Chaer RA, et al. Treatment strategies of arterial steal after arteriovenous access. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.10.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steerman SN, Wagner J, Higgins JA, Kim C, Mirza A, Pavela J, et al. Outcomes comparison of HeRO and lower-extremity arteriovenous graft in patients with longstanding renal failure. Presented at the Society of Vascular Surgery 2012 Annual Meeting; National Harbor, Md. June 2012; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day JD, Holt HR, Chen BL, Stout CL, Panneton JM, Glickman MH. Hemodialysis Reliable Outflow (HeRO) catheter outcomes in patients with long-standing renal failure: optimizing performance. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:1072. [Google Scholar]