Abstract

A number of antitumor vaccines have shown recent promise up-regulating immune responses against tumor antigens and improving patient survival. In this study we examine the effectiveness of vaccination using IL-15 expressing tumor cells and examined their ability to up-regulate immune responses to tumor antigens. We demonstrated that the co-expression of IL-15 with its receptor, IL-15Rα, increased the cell-surface expression and secretion of IL-15. We show that a gene transfer approach using recombinant adenovirus to express IL-15 and IL-15Rα in murine TRAMP-C2 prostate or TS/A breast tumors induced antitumor immune responses. From this we developed a vaccine platform, consisting of TRAMP-C2 prostate cancer cells or TS/A breast cancer cells co-expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα that inhibited tumor formation when mice were challenged with tumor. Inhibition of tumor growth led to improved survival when compared to animals receiving cells expressing IL-15 alone or unmodified tumor cells. Animals vaccinated with tumor cells co-expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα showed greater tumor infiltration with CD8+ T and NK cells, as well as increased antitumor CD8+ T-cell responses. Vaccination with IL-15/IL-15Rα-modified TS/A breast cancer cells provided a survival advantage to mice challenged with unrelated murine TUBO breast cancer cells indicating the potential for allogeneic IL-15/IL-15Rα expressing vaccines.

Keywords: Cancer, gene therapy, interleukin-15, interleukin-15 receptor-alpha, vaccine

Introduction

Tumor cell vaccines have shown preclinical promise and antitumor activity in patient trials in a number of malignancies including breast, prostate, and pancreatic cancer, and leukemia (reviewed in 1). These vaccines have the advantage over single antigen vaccines in that they can target multiple known and unknown tumor-associated antigens (TAA). The whole tumor cell vaccine platform that has been the furthest developed is GVAX, which consists of irradiated autologous or allogeneic tumor cells genetically modified to secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). GVAX has been shown to induce the infiltration of dendritic cells to the vaccination site, and stimulate CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses, as well as antibody responses (reviewed in 2). The clinical outcome of phase III trials of GVAX; however, have been disappointing. Two randomized, controlled phase III trials of GVAX in prostate cancer (VITAL-1 and VITAL-2) were terminated due to a lack of efficacy compared to standard chemotherapy with docetaxel and prednisone3,4. In the VITAL-2 study an increase in patient deaths was also noted in the GVAX arm.

Interleukin-15 (IL-15) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine capable of stimulating the differentiation and proliferation of T-, B-, and natural killer (NK) cells. It is essential for the differentiation and maintenance of memory CD8+ T-cells and NK/T cells5. It can also promote the development of dendritic cells6. IL-15 function is mediated through its heterotrimeric receptor composed of the IL-15Rα, IL-2R/IL-15Rβ (CD122), and the common cytokine receptor γ-chain (γc, CD132)7,8. IL-15 is tightly bound by IL-15Rα alone; anchoring it on the surface of antigen presenting cells and limiting its secretion. Signaling is initiated by presentation of IL-15 by IL-15Rα in “trans” to the IL-2R/IL-15Rβ and γc expressed on the effector cells9. The co-expression of IL-15 and IL-15Rα on non-lymphoid cells such as antigen presenting cells has been shown to be required to support its “trans” presentation and activation of effector cells10. In HIV infection, the coordinated dysregulation of IL-15 and IL-15Rα has been shown to occur in progressive disease underlying the importance of co-expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα11.

We utilized IL-15 to develop a whole tumor cell vaccine targeting murine breast and prostate cancer. We show that tumor cells transduced with IL-15 inhibited tumor growth in vivo and this was enhanced when IL-15Rα was also co-expressed by the tumor cells. Vaccination with modified tumor cells expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα inhibited tumor formation and led to increased survival. Furthermore, we show that the immune responses induced by vaccination are mediated by CD8+ T-cells and NK cells.

RESULTS

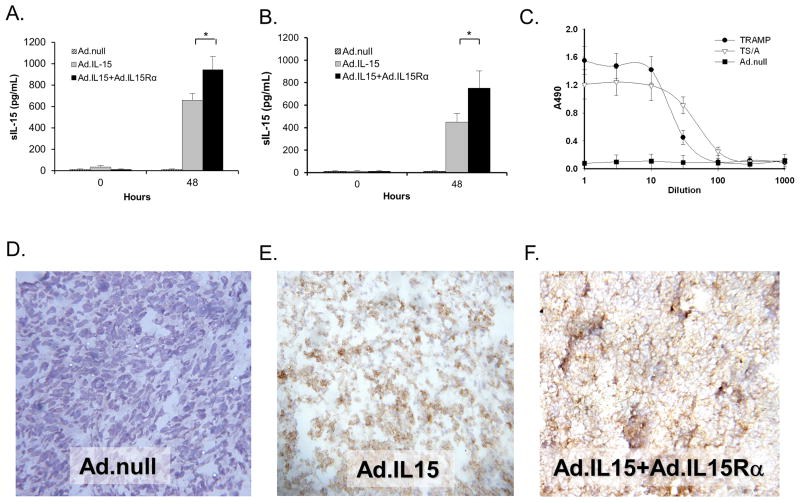

Tramp-C2 and TS/A cells express IL-15 following transduction with Ad.mIL15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα

To examine if TRAMP-C2 and TS/A cells could be made to express IL-15, we transduced them with, Ad.mIL-15, Ad.null, or Ad.mIL-15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα and examined IL-15 secretion by ELISA. We found that neither TRAMP-C2 nor TS/A cells natively secrete detectable levels of IL-15 and did not secrete IL-15 in response to transduction with a control vector, Ad.null. Both cell lines expressed IL-15 following transduction with Ad.mIL-15 alone or in combination with Ad.mIL-15Rα (Fig. 1A & 1B). Significantly higher levels of IL-15 were detected in the supernatants of cells transduced with both Ad.mIL-15 and Ad.mIL-15Rα when compared to those infected with Ad.mIL-15 alone (p<0.01). We confirmed the functional status of the secreted IL-15 by its ability to induce proliferation of CTLL-2 cells. Culture media from TRAMP-C2 or TS/A cells transduced with Ad.mIL-15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα induced the proliferation of CTLL-2 cells, while those transduced with Ad.null did not (Fig. 1C). The media retained its ability to induce CTLL-2 proliferation to a dilution of 1:1000.

Figure 1. Cells transduced with IL-15 and IL-15Rα express functional IL-15.

A. TRAMP-C2, or B. TS/A cells were transduced with adenoviruses expressing IL-15, IL-15 and IL-15Rα or an Ad.null (empty vector) at an MOI of 100; 48H later the media was removed and assayed for secreted IL-15 by ELISA. N = 6 per treatment; *p<0.05. Error bars = SD. C. The supernatants of TRAMP-C2 or TS/A cultures transduced with Ad.IL-15 + Ad.IL-15Rα, or Ad.null were serially diluted and incubated with CTLL-2 cells. Proliferation of CTLL-2 cells after 48 hours was determined using the CellTiter 96® AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay. Error bars = SD. D. Ad.null, E. Ad.IL-15, F. Ad.IL-15 + Ad.IL-15Rα transduced TS/A cells were injected into BALB/c mice and tumors grown. Immunohistochemistry was performed on the resulting tumors examining IL-15 expression. IL-15 expression is depicted by brown staining.

In order to determine the cellular localization of IL-15 following transduction with Ad.mIL-15, Ad.null or Ad.mIL-15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα, we examined transduced TS/A tumors by immunohistochemistry. TS/A tumors that had been infected with Ad.null did not exhibit any IL-15 staining whereas those transduced with either Ad.mIL-15 alone or in combination with Ad.mIL-15Rα showed significant IL-15 staining (Fig. 1D–F). TS/A cells transduced with Ad.mIL-15 alone expressed IL-15 throughout the cell while those that had been transduced with both Ad.mIL-15 and Ad.mIL-15Rα exhibited IL-15 staining predominantly at the surface of the cell.

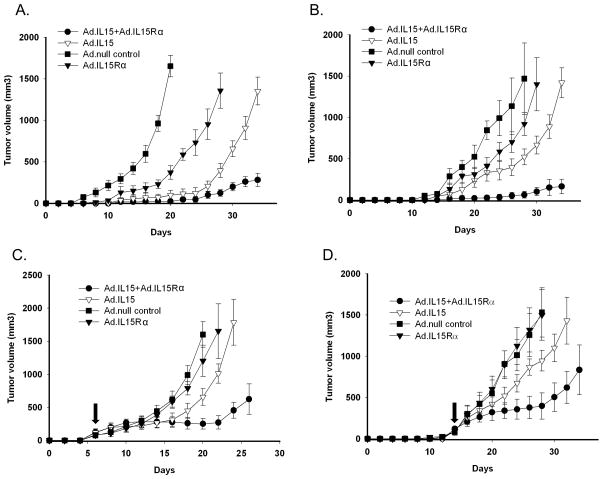

TRAMP-C2 and TS/A cells expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα significantly inhibited tumor growth

In order to examine the effects of IL-15 and IL-15Rα expression on tumor growth we transduced TS/A and TRAMP-C2 cells with Ad.mIL-15 with or without Ad.mIL-15Rα and s.c. injected them into syngeneic BALB/c or C57Bl/6 mice, respectively. We found that the expression of IL-15 alone or in combination with IL-15Rα inhibited the growth of TS/A (Fig. 2A) and TRAMP-C2 tumors (Fig. 2B) (p<0.05). In both tumor lines, the added expression of IL-15Rα further inhibited tumor growth when compared to IL-15 alone. IL-15Rα alone also reduced tumor growth in TS/A (p<0.05).

Figure 2. Tumor growth is inhibited following transduction with IL-15 and IL-15Rα.

A. TS/A or B. TRAMP-C2 cells were transduced with Ad.null, Ad.IL-15, Ad.mIL-15Rα or Ad.IL-15 + IL-15Rα at an MOI of 100. After 24 hours 5 × 105 cells were transplanted into mice. Mice were evaluated daily for tumor growth. N = 10 per group. C. TS/A, or D. TRAMP-C2 tumors were grown to 75–125 mm3 in BALB/c or C57Bl/6 mice then injected intratumorally with Ad.mIL-15, Ad.mIL-15Rα, Ad.mIL-15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα or Ad.null at 1 × 109 PFU. Arrows indicate injection time point. Mice were evaluated daily for tumor growth. N = 10 per group. Error bars = SEM.

To further show that IL-15 expression by tumors could inhibit tumor growth, we injected Ad.mIL-15, Ad.mIL-15Rα, Ad.mIL-15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα, or Ad.null into actively growing TS/A or TRAMP-C2 tumors in vivo. Ad.mIL-15 or Ad.mIL-15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα resulted in significant tumor growth reduction when compared to Ad.null (p<0.05). The combination of IL-15 and IL-15Rα inhibited the growth of both TS/A (Fig. 2C) and TRAMP-C2 (Fig. 2D) tumors (p<0.05). Ad.mIL-15Rα did not reduce the growth of either TS/A or TRAMP-C2 tumors compared to Ad.null and therefore this group was not continued.

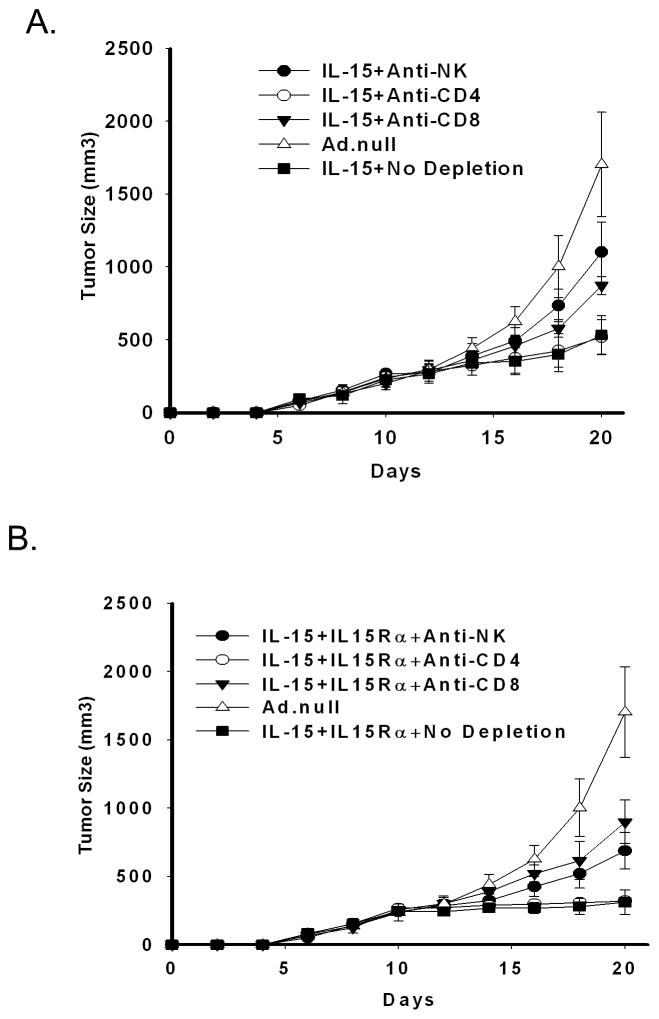

Growth inhibition mediated by IL-15 and IL-15Rα is CD8+ and NK dependent

To determine which cell population is important in the inhibition of tumor growth following transduction with IL-15 with or without IL-15Rα, we depleted CD8+ T-cells, CD4+ T-cells or NK cells and looked for an abrogation of tumor suppression. Depletion of CD4+ cells did not affect tumor growth kinetics in animals treated with either IL-15 alone (Fig. 3A), or in combination with IL-15Rα (Fig. 3B). However, depletion NK or CD8+ cells inhibited IL-15 induced tumor growth suppression (NK, p=0.005; CD8+, p=0.011) and IL-15 + IL-15Rα (NK, p=0.025; CD8+, p<0.001) indicating a role of these cells in the antitumor effect. In animals with tumors transduced with IL-15 alone, the depletion of NK cells showed the greatest abrogation of tumor response, whereas when IL-15 was combined with IL-15Rα, CD8+ depletion demonstrated greater attenuation of tumor responses.

Figure 3. Cells transduced with IL-15 and IL-15Rα induce a CD8 and NK cell mediated anti-cancer immune response.

5 × 105 TS/A cells were transduced with A. Ad.IL-15 alone or B. Ad.IL-15 + AdIL-15Rα and transplanted into BALB/c mice. CD4+, CD8+, and NK cells were depleted from the mice using injections of 200 μg of anti-CD4 (GK1.5) or anti-CD8 (2.43) or 50 μg of anti-NK (anti-asialo GM1) antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Mice were followed for tumor growth (10 mice per group). Error bars = SEM.

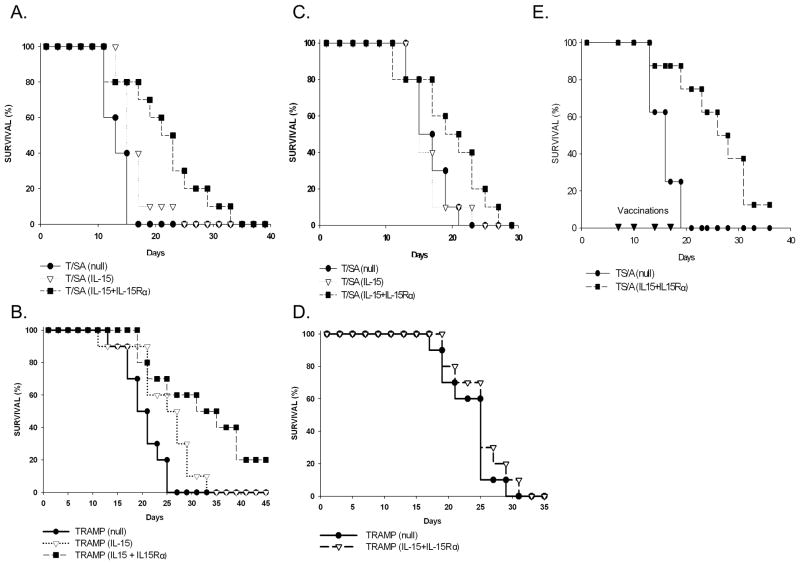

A cellular vaccine expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα increased survival

Given that the expression of IL-15 and IL-15Rα by tumor cells can induce an antitumor response that is CD8+ mediated, we examined the ability of modified TRAMP-C2 and TS/A cells to act as a vaccine platform. To do this we infected TRAMP-C2 and TS/A with Ad.mIL-15 with or without Ad.mIL-15Rα and treated them with mitomycin C to inhibit their growth. We injected the cells into the flanks of BALB/c or C57Bl/6 mice and 2 weeks later challenged the mice with unmodified TS/A or TRAMP-C2 cells, respectively on the opposite flank. Mice vaccinated with TS/A cells expressing IL-15 did not have significantly greater survival than those vaccinated with TS/A transduced with Ad.null (Fig. 4A). However, mice vaccinated with TS/A expressing both IL-15 and IL-15Rα had significantly improved survival compared to those vaccinated with TS/A expressing IL-15 alone or Ad.null (p=0.001). Similarly, mice vaccinated with TRAMP-2 expressing both IL-15 and IL-15Rα had significantly greater survival than those transduced with the Ad.null control vector; p=0.004 (Fig. 4B). Unlike TS/A cells, the transduction of TRAMP-C2 cells with IL-15 alone lead to a significant survival advantage over that observed with Ad.null (p=0.01); however, this was significantly less than that of IL-15 combined with IL-15Rα (p=0.039). When we challenged mice vaccinated with TS/A expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα with the unrelated TUBO breast cancer cell line there was a survival advantage over those vaccinated with TS/A alone (Fig. 4C). Mice vaccinated with TRAMP-C2 expressing IL-15 + IL-15Rα and challenged with MC38 colorectal tumors did not demonstrate inhibition of tumor growth; p=0.33 (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. Vaccinating mice with IL-15 and IL-15Rα significantly prolongs the survival of mice challenged with tumor.

Mice were immunized with 1 × 106 MMC treated TS/A or TRAMP-C2 cells transduced with Ad.null, Ad.IL-15 alone, Ad.IL-15Rα alone or Ad.IL-15 + AdIL-15Rα respectively into their left flanks. Two weeks later the mice were challenged with 5 × 105 A. TS/A, B. TRAMP-C2, C. TUBO or D. MC38 cells in their right flanks and the mice evaluated for survival (10 mice per group). MMC treated cells transduced with Ad.IL-15 + AdIL-15Rα improved survival in animals challenged with A. TS/A (P=0.001), B. TRAMP-C2 (P=0.004), C. TUBO (P=0.043) but not D. MC38 cells (P=0.33) compared to Ad.null. E. Mice were implanted with 1 × 105 TS/A cells into their left flank. 7, 10, 14 and 17 days later (▼) the animals were treated with 1 × 106 MMC treated TS/A cells transduced with Ad.null, or Ad.IL-15+AdIL-15Rα into their right flanks. The mice were followed for survival (N=8). MMC treated cells transduced with Ad.IL-15 + AdIL-15Rα improved survival in animals with pre-established tumors (P=0.002).

In a proof of principle experiment designed to show the efficacy of the vaccine against an established tumor, we implanted highly aggressive and poorly immunogenic TS/A cells on one flank of the mouse, allowed the tumors to grow for 7 days, to a mean volume of 130 mm3, and then vaccinated the mice on the opposite flank with mitomycin C treated TS/A cells expressing IL-15/IL15Rα or TS/A tumors transduced with Ad.null (control). Mice were similarly vaccinated on days 10, 14 and 17, for a total of 4 vaccinations. By the completion of the vaccination cycle 87% of the mice treated with TS/A expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα were alive compared to 25% of those treated with the TS/A-Ad.null control. All deaths were due to tumor burden. Animals vaccinated with TS/A expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα had significantly increased survival compared to those vaccinated with TS/A transduced with Ad.null; p=0.002 (Fig. 4E).

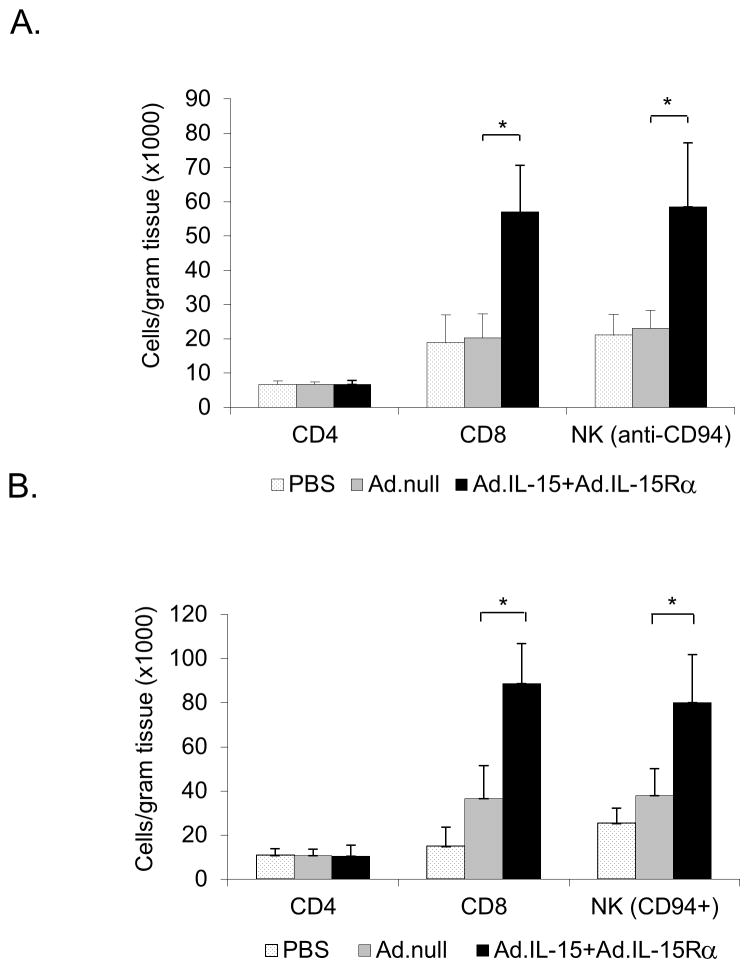

Vaccination with tumor cells expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα induce greater tumor infiltration of immune effector cells

To further examine the effectiveness of the tumor cell vaccine we examined the number of tumor infiltrating CD8+, CD4+ and NK (CD94) cells within the tumors (Fig. 5). We found that mice vaccinated with TS/A or TRAMP-C2 expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα had more tumor infiltrating CD8+ and NK cells per gram of tumor than tumors from mice vaccinated with cells transduced with Ad.null. In mice vaccinated with TS/A expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα there were 2.8-fold more CD8+ and 2.5-fold more NK cells when compared to mice vaccinated with TS/A + Ad.null (Fig. 5A). A similar effect was seen following vaccination with TRAMP-C2 cells expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα with 2.5-fold more CD8+ cells and 2.7-fold more NK cells when compared to the tumors of unvaccinated animals (Fig. 5B). When looking at CD4+ T-cell infiltrates we found no differences in the relative numbers of these cells in either TRAMP-C2 or TS/A tumors.

Figure 5. Vaccination with IL-15 + IL-15Rα induces increased tumor infiltration of CD8 and NK cells.

Mice were immunized with 1 × 106 MMC treated A. TS/A or B. TRAMP-C2 cells transduced with Ad.IL-15+AdIL-15Rα and challenged with TS/A or TRAMP-C2 respectively. Tumors were isolated, disaggregated and treated enzymatically (DNase, 300 U/mL, + hyaluronidase, 0.1%, + collagenase, 1%) to make a single cell suspension. The cells were examined by flow cytometry for CD8, CD4 and CD94 (NK marker) cells. N=3 per tumor type. *p<0.05. Error bars = SD.

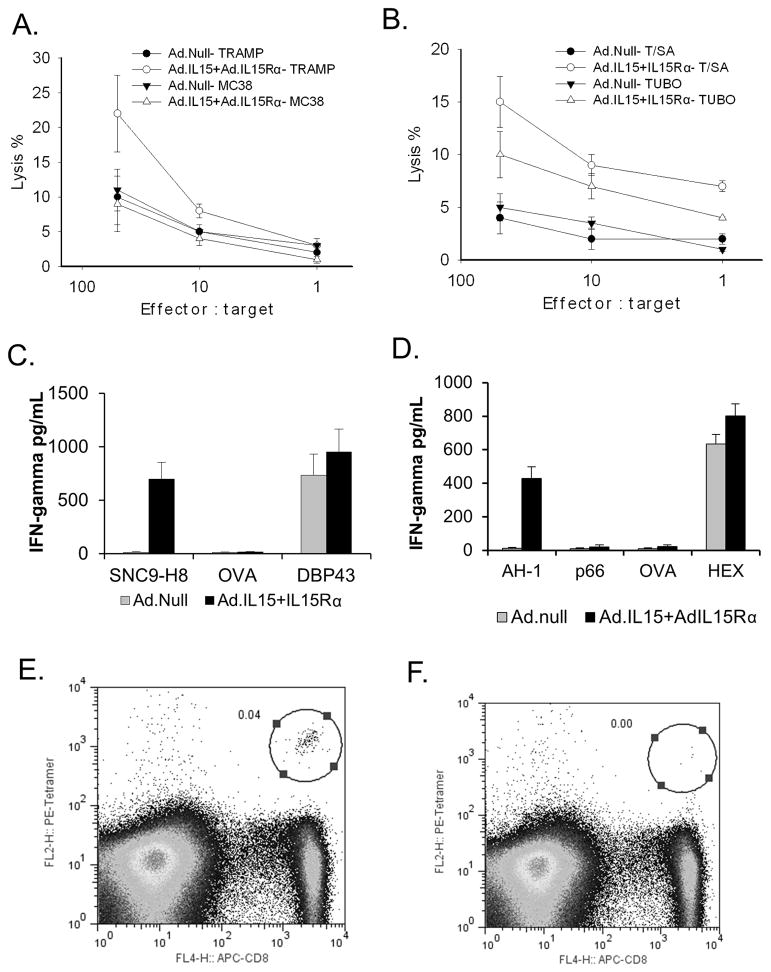

Vaccination with TRAMP-C2 or TS/A cell expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα induces cell-mediated immune responses

In order to assess the tumor-specific effects of the vaccine we examined the ability of splenocytes from TRAMP-C2 and TS/A vaccinated mice to lyse the respective unmodified tumor cells ex vivo. After stimulation with tumor antigens, splenic cells isolated from TRAMP-C2-Ad.null treated mice demonstrated little lytic activity against TRAMP-C2 or MC38 cells (Fig. 6A), whereas spleen cells isolated from TRAMP-C2-IL-15/IL-15Rα showed increased lytic activity against TRAMP-C2 cells, but not against murine MC38 colon cancer. Similarly, splenocytes isolated from TS/A-Ad.null treated mice showed little lytic activity, whereas those isolated from TS/A-IL-15/IL-15Rα showed increased lytic activity against TS/A and TUBO cells indicating a tumor-specific immune response (Fig. 6B). Greater lytic activity was shown against TS/A cells as compared to TUBO cells. To confirm that the lytic activity seen was directed against the CD8 immunodominant tumor antigens we assessed the ability of splenocytes from animals vaccinated with TRAMP-C2 or TS/A expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα or an Ad.null to secrete IFN-γ in response to SNC9-H8, CD8-restricted TRAMP-C2 immunodominant peptide, or AH1, a CD8-restricted TS/A immunodominant peptide. Splenocytes from mice vaccinated with either TRAMP-C2 or TS/A cells expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα secreted significantly more IFN-γ than those isolated from mice vaccinated with TRAMP-C2 or TS/A expressing Ad.null when exposed to SNC9-H8 or AH1, respectively (p<0.01) (Fig. 6C & D). No IFN-γ was release was seen when exposed to OVA or p66, whereas IFN-γ was released from splenocytes of the IL-15/IL-15Rα or Ad.null treated animals exposed to HEX486-494 or DBP43, immunodominant epitopes of adenovirus. In addition to increased lytic activity or IFN-γ release, animals vaccinated with TRAMP-C2 expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα had more SPAS-1 tetramer specific CD8+ cells (Fig. 6E) compared to those vaccinated with TRAMP-C2 cells transduced with Ad. Null (Fig. 6F), or untreated animals (data not shown).

Figure 6. Vaccination with IL-15 and IL-15Rα induced cell-mediated immune responses.

Mice were vaccinated with MMC treated TRAMP-C2 or TS/A cells. Splenocytes were isolated and examined for their ability to lyse TRAMPC-2 or MC38 cells (A.) or TS/A or TUBO cells (B.); or induce IFN-γ release in response to co-culture with SNC9-H8 (TRAMP immunodominant antigen), OVA or DBP43 (adenovirus immunodominant antigen) peptides (C.) or AH-1 (TS/A immunodominant peptide), p66 (TUBO immunodominant antigen), ova or HEX (adenovirus immunodominant antigen) (D.). N = 3. Splenocytes from mice vaccinated with TRAMP-C2 transduced with IL-15 + IL-15Rα (E.) or Ad.null (F.) were also examined for the presence of tetramer positive CD8 cells by flow cytometry. Error bars = SD.

Discussion

IL-15 is a powerful proinflammatory cytokine that can enhance innate and adaptive immune responses (reviewed in 12). Recently, recombinant human lL-15 has entered clinical trials for treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma and renal cell carcinoma13. In pre-clinical studies, IL-15 has been shown to be active as a single agent or in combination with other immune modulating agents, such as anti-CD40, anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-414–16. Due to its immunostimulatory effects, IL-15 is also being studied as a vaccine adjuvant17–19. We and others demonstrated that the co-expression of IL-15 along with its receptor, IL-15Rα, as a vaccine, enhanced the biological activity of IL-1520–23. Here we showed that murine TS/A and TRAMP-C2 tumor cells can be transduced with adenoviruses expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα, and that the cells secrete functional IL-15. Bergamaschi et al, reported that IL-15 and IL-15Rα bind intracellularly and that this interaction stabilizes the protein allowing IL-15 to be secreted; whereas, when IL-15 is expressed in the absence of IL-15Rα it is rapidly degraded allowing only limited amounts to be secreted24,25. In line with this, we showed that TS/A and TRAMP-C2 cells expressing both IL-15 and IL-15Rα secreted greater quantities of IL-15 than these cells expressing IL-15 alone.

In humans, very little IL-15 is detected in the serum, rather IL-15 is predominantly found on the surface of cells bound to its receptor. Most IL-15 detected in the blood is thought to be bound to soluble IL-15Rα cleaved from the surface of cells. IL-15Rα has been shown to trans-present the cytokine to effector cells9. The trans-presentation of IL-15 by IL-15Rα is the primary way in which IL-15 signals through the β and γ-chains of the IL-15 receptor and that both IL-15 and IL-15Rα are required to be expressed by the same cell to allow trans-presentation to occur10,26. This complex signaling mechanism may act to regulate the effects of IL-15 by allowing tightly controlled and directed delivery to the effector cells (reviewed in 27). From this, we posited that the co-expression of IL-15 and IL-15Rα on tumor cells would allow the surface trans-presentation by the tumor cells to effector cells to stimulate an anti-tumor response. We found that co-expressing IL-15 with IL-15Rα lead to IL-15 expression on the surface of the tumor cells while the expression of IL-15 alone showed diffuse cytoplasmic localization within the cells (Fig 1.). The requirement for IL-15Rα for the cell surface expression of IL-15 is supported by Bergamaschi et al. who showed that little IL-15 is detected on the cell surface following the transfection with a plasmid expressing IL-15 alone, whereas when they combined IL-15 with IL-15Rα they were able to detect IL-15 expression on the surface of the cells25.

In terms of function, we showed that co-expression of IL-15 and IL-15Rα in TS/A breast or TRAMP-C2 prostate cancer cells resulted in smaller tumors than when the cells expressed IL-15 alone. These effects were seen when the tumor cells were transduced with IL-15 and IL-15Rα prior to implantation or when IL-15 and IL-15Rα was delivered into pre-established tumors. A number of studies have shown that gene delivery of IL-15 into tumor cells can induce an antitumor response28–31. In this study we showed that tumor cells transduced with IL-15 alone did have an antitumor effect when compared to the Ad.null control; however, this was significantly less than that seen when IL-15 was combined with IL-15Rα.

IL-15 has been reported to induce tumor cell killing through the stimulation of NK and CD8+ T-cells (reviewed in 12). We showed that the depletion of NK cells and CD8+ lymphocytes limited the antitumor effect of treatment with IL-15 and its receptor, providing evidence that in our models NK and CD8+ T-cells play an essential role. This is in line with results shown by Dubois et al. using soluble IL-15/IL-15Rα-IgG1-Fc complexes32. The ability of IL-15 and its receptor to induce a CD8+ T-cell response directed against the tumor following the transduction of the tumor cells with IL-15 and IL-15Rα pointed at this combination’s potential to be used as a vaccine. Genetically modified tumor cell vaccines such as GVAX, engineered to express GM-CSF, that demonstrated activity in early clinical trials1,2 have failed to show efficacy in phase III trials3,4. Further, in the GVAX phase III trial comparing GVAX and docetaxel to docetaxel and prednisone, there was greater risk of death associated with the vaccine treatment. The strong pro-inflammatory characteristics of IL-15 and the predominantly cell bound nature of IL-15, when combined with IL-15Rα, and its requirement of trans-presentation for effector cell activation may allow IL-15/IL-15Rα expressing tumor cells to induce a safer more targeted immune response than previously studied tumor vaccines.

To examine the efficacy of a IL-15/IL-15Rα expressing tumor cell vaccine, we transduced mouse TS/A breast cancer or TRAMP-C2 prostate cancer cells with Ad.IL-15 and Ad.IL-15Rα, and used these cells as a vaccine. We showed that this vaccine stimulated an antitumor immune response leading to a significant prolongation of survival when animals were challenged with TS/A or TRAMP-C2 cells. Tumors isolated from these animals had greater levels of CD8+ and NK cells per gram of tissue than those tumors isolated from mice vaccinated with control cells not expressing IL-15 + IL-15Rα. CTL assays also showed that splenocytes isolated from IL-15/IL-15Rα vaccinated mice could lyse TS/A or TRAMP-C2 tumor cells ex vivo and secrete IFN-γ in response to stimulation with a CD8+ immunodominant peptide. In addition, vaccination with TRAMP-C2 cells expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα induced TRAMP-C2 tetramer specific CD8+ cells as evidenced by tetramer staining. Mice vaccinated with TRAMP-C2 prostate cancer cells expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα and challenged with MC38 colon cancer cells did not demonstrate a survival advantage over TRAMP-C2 cells transduced with Ad.null, nor did splenocytes isolated from these animals lyse MC38 cells ex vivo.

Interestingly, mice vaccinated with TS/A expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα and challenged with TUBO had a prolonged survival compared to those vaccinated with TS/A alone. CTL assays also showed that splenocytes isolated from mice vaccinated with TS/A expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα were also able to lyse TUBO cells ex vivo, but did not secrete IFN-γ when stimulated with an immunodominant peptide for TUBO (p66) or TS/A (AH1). Tumor lysis, despite a lack of IFN-γ secretion when stimulated with the immunodominant peptides, suggests that the tumor cell vaccine was targeting an unknown antigen. Both TS/A and TUBO are murine breast cancer cell lines derived from BALB/c mice and may share a number of unidentified tumor-associated antigens. Tumor cells expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα may have an advantage over other allogeneic tumor vaccines in that IL-15 can overcome immunodominance by enhancing immune responses to subdominant antigens33. This may broaden the antitumor response allowing shared subdominant tumor antigens to be targeted thereby increasing the potential for success when using IL-15 and IL-15Rα to augment allogeneic vaccinations. In addition, the use of whole tumor cells as the base of this vaccine allows the potential targeting of multiple uncharacterized tumor antigens, unlike other vaccine strategies such as genetically engineered dendritic cells21 or viral vaccines18 where specific antigens must be identified in the tumor and vectors designed around those antigens.

We also showed that IL-15/IL-15Rα expressing tumor vaccines are effective in a clinically relevant therapeutic setting. Mice harboring poorly immunogenic and highly aggressive TS/A tumors could be effectively treated with IL-15/IL-15Rα expressing tumor vaccines leading to a significant prolongation of survival.

In summary, co-expression of IL-15 and IL-15Rα resulted in robust levels of IL-15 secretion by tumor cells and in turn lead to a greater antitumor immune response. Genetically altering tumor cells to co-express IL-15 and IL-15Rα can induce and enhance immune responses to tumor antigens found on these tumor cells. These cells can be used as a vaccine to target these antigens. IL-15 may also augment the immune responses to subdominant antigens increasing the potential to use allogeneic tumor cell vaccines. The findings in the current study provide the scientific rationale for the investigation of this vaccine platform in clinical trials in cancer to determine whether genetically modified tumor cells expressing IL-15 and IL-15Rα may induce anti-cancer responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

TS/A and TUBO mouse mammary carcinoma cell lines were derived from a BALB/c background and were gifts from Dr. Patrizia Nanni (University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy)34,35 and were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, BioSource, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini, Calabassas, CA) and 10 μg/mL gentamicin sulfate (BioSource). Human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells and murine TRAMP-C2 prostate cancer cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS and 10 μg/mL gentamicin sulfate (BioSource). MC38 murine colon cancer cells were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS and 10 μg/mL gentamicin sulfate (BioSource). TRAMP-C2 and MC38 cells were derived on a C57Bl/6 background. CTLL-2 cytotoxic T cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 200 U/ml IL-2.

Adenoviruses

The murine IL-15 and IL-15Rα cDNAs34 were provided by Dr. Yutaka Tagaya (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD). Ad.mIL-15 and Ad.mIL-15Rα are E1, E3-deleted recombinant adenoviruses (rAd) expressing the murine IL-15 or IL-15Rα, respectively. Ad.null is an E1, E3-deleted rAd control vector expressing no transgene. All vectors were generated using the AdMax system (Microbix)36; double plaque-isolated, expanded on HEK-293 cells, purified on two-step and continuous CsCl gradients or an anion-exchange column (Sartorius Stedim, Bohemia, NY), titered as plaque-forming units (pfu)/mL, and stored at −70°C.

Peptides

Synthetic peptides SNC9-H8 (STHVNHLHC), a dominant TRAMP-C2 epitope37; AH1 (SPSYVYHQF), a dominant TS/A epitope38, p66 (TYVPANASL), a dominant rat NEU epitope39; HEX486–494 (KYSPSNVKI) or dbp43 (FALSNAEDL), dominant adenovirus epitopes40, and OVA257–264 (SIINFEKL), an epitope from hen ovalbumin40 were purchased from Genscript (Piscataway, NJ).

Animals

Male 6–8 week old C57Bl/6 mice and female 6–8 week old BALB/c mice were obtained from the Division of Cancer Research and Treatment, National Cancer Institute (NCI; Frederick, MD). All the animals were maintained in the NCI animal holding facility and their use adhered to the NIH Laboratory Animal Care Guidelines and was approved by the NCI Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometry

SPAS-1 tetramer was previously described14. Cell surface expression of CD8, CD4 and CD94 was performed using antibodies from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR)

IL-15 secretion and activity

Culture supernatants were removed prior to and 48 hours after infection of tumor cells with Ad.mIL-15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα or Ad.null each at an MOI of 100. Supernatants were assayed for murine IL-15 by ELISA (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) as per manufacturer’s instructions. To assess the functionality of secreted IL-15, supernatants were diluted and incubated with CTLL-2 cells41. Proliferation of CTLL-2 cells at 48 hours was determined using the CellTiter 96® AQueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison WI) as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemisty

Tumors from TS/A cells infected with Ad.mIL-15, Ad.mIL-15 and Ad.mIL-15Rα or Ad.null each at an MOI of 100 were resected, fixed in OCT (SAKURA-Finetek, Torrance, CA) and sectioned by cryostat. Tissue sections were treated with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide, then treated with Avidin/Biotin blocking kit (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The sections were stained with goat anti-mouse IL-15 (R &D systems). The slides were washed and stained using the anti-goat HRP-DAB Cell and Tissue staining kit (R&D Systems) as per the manufacturer’s instructions and counterstained with hematoxylin.

Treatment effect

TS/A and TRAMP-C2 cells were seeded in 175 cm2 tissue culture flasks at 1 × 107 cells/flask and transduced with Ad.mIL-15, Ad.mIL-15Rα, Ad.mIL-15+Ad.mIL-15Rα or Ad.null at MOI of 100. Cells were harvested after 24 hours and groups of 10 mice were subcutaneously (s.c.) injected with 5 × 105 transduced cells. Mice were evaluated daily for tumor growth.

In a separate experiment 5 × 105 TS/A or TRAMP-C2 cells were injected s.c. into the flanks of BALB/c and C57Bl/6 mice respectively (10 mice per treatment). When the tumors reached 75–125 mm3 they were intratumorally injected with Ad.mIL-15, Ad.mIL-15Rα, Ad.mIL-15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα or Ad.null at 1 × 109 PFU. Mice were evaluated daily to assess tumor growth. Tumor volumes (V) were calculated using the formula: V = (l × w)2/2.

Immune cell depletion

Groups of BALB/c mice were depleted of specific immune cell populations21. Briefly, CD4+ or CD8+ cells were depleted with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 antibodies purified from the supernatants of hybridomas GK1.5 (ATCC) and 2.43 (ATCC), respectively. Five days before vaccination with TS/A transduced with IL-15, IL-15 + IL-15Rα or Ad.null, mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with 200 μg of the appropriate antibody for 3 consecutive days and continued every 3 days thereafter for the duration of the experiment. To deplete NK cells, anti-asialo GM1 50 μg (WAKO, Richmond, VA) was administered beginning 5 days before tumor implantation for 3 consecutive days and then continued every 3 days thereafter. Greater than 95% depletion of specific lymphocyte populations was confirmed by peripheral blood flow cytometry.

Vaccinations

TS/A and TRAMP-C2 cells were seeded at 1 × 107 cells/flask into 175 cm2 tissue culture flasks and transduced with Ad.mIL-15, Ad.mIL-15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα, or Ad.null at an MOI of 100. After 24 hours the cells were treated with mitomycin C (MMC) at 0.5 mg/mL for 30 minutes at 37°C to inhibit cell proliferation. Groups of BALB/c and C57Bl/6 mice were immunized with 1 × 106 MMC-TS/A and MMC-TRAMP-C2 cells respectively into their left flanks. Two weeks later the mice were challenged with 5 × 105 TS/A, TUBO, MC38 or TRAMP-C2 cells in their right flanks and the mice evaluated for survival.

In a separate experiment 1 × 105 TS/A cells were implanted into the left flank of BALB/c mice. Seven days later, when tumors were approximately 130 mm3, the mice were injected s.c. with 1 × 106 MMC-TS/A expressing IL-15/IL-15Rα or Ad.null (as above) in the right flank. Animals were similarly vaccinated on days 10, 14 and 17 and assessed for tumor growth (N = 8 per group).

Cytokine secretion and cytotoxicity assays

Spleen single cell suspensions were prepared from mice sacrificed on day 21 after MMC-TRAMP-C2 or MMC-TS/A vaccination and cultured with MMC treated (0.5 mg/mL) TRAMP-C2, MC38, TUBO or TS/A tumor cells at a ratio of 50:1, 10:1, 1:1. Recombinant human IL-2 was added to a concentration of 10–15 U/mL. After 4 days, cytotoxicity assays were performed: effector cells from each groups were cultured with 104 TRAMP-C2, MC38, TUBO or TS/A target cells/well in triplicate at varying E/T ratios and incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. Cytotoxic activity was measured by LDH release using the CytoTox 96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega, Madison, WI). The percent lysis was calculated as 100 × ([experimental release] − [effector spontaneous release] − [target spontaneous release])/([target maximum release] − [target spontaneous release]).

To detect a CD8+ response against the TRAMP-C2 or TS/A, splenocytes were assayed for IFN-γ secretion. Splenocytes from groups of animals (N = 3) vaccinated with MMC-TS/A or MMC-TRAMP transduced with Ad.mIL-15, Ad.mIL-15 + Ad.mIL-15Rα or Ad.null were pooled and plated at 2 × 106 cells per well in 24-well plates in triplicate. Splenocytes were co-cultured with 10 μg/mL of the CD8 dominant peptides: SNC9-H8, AH1, OVA257-264, p66, DBP43 or HEX486-494 for 72 h. Supernatants were collected and IFN-γ was measured by ELISA (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were tested in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Statistical Software version 5.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Kaplan-Meier nonparametric regression analyses were performed for tumor prevention experiments with significance determined by the log-rank test. The comparison of the effect of vaccination on antibody titers among different groups was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey-Kramer honestly significant difference or nonparametric Wilcoxon/Kruskal-Wallis tests. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, the University of Cincinnati Cancer Institute, Cincinnati, OH, and a grant from the Lcs Foundation, Cincinnati, OH.

Footnotes

Disclosure of any potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Keenan BP, Jaffee EM. Whole cell vaccines--past progress and future strategies. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:276–286. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eager R, Nemunaitis J. GM-CSF gene-transduced tumor vaccines. Mol Ther. 2005;12:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higano CSF, Somer B, Curti B, Petrylak D, Drake C, Schnell F, Redfern C, Schrijvers D, Sacks NA. A phase III trial of GVAX immunotherapy for prostate cancer versus docetaxel plus prednisone in asymptomatic, Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (CRPC) [Abstract]. ASCO Genitourinary Cancers Symposium; 2009. p. LBA150. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Small EDT, Gerritsen W, Rolland F, Hoskin P, Smith D, Parker C, Chondros D, Ma J, Hege K. A phase III trial of GVAX immunotherapy for prostate cancer in combination with docetaxel versus docetaxel plus prednisone in symptomatic, Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer [Abstract]. ASCO Genitourinary Cancers Symposium; 2009. p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, Butz EA, Viney JL, Embers M, et al. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:771–780. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pulendran B, Dillon S, Joseph C, Curiel T, Banchereau J, Mohamadzadeh M. Dendritic cells generated in the presence of GM-CSF plus IL-15 prime potent CD8+ Tc1 responses in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:66–73. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giri JG, Ahdieh M, Eisenman J, Shanebeck K, Grabstein K, Kumaki S, et al. Utilization of the beta and gamma chains of the IL-2 receptor by the novel cytokine IL-15. Embo J. 1994;13:2822–2830. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giri JG, Kumaki S, Ahdieh M, Friend DJ, Loomis A, Shanebeck K, et al. Identification and cloning of a novel IL-15 binding protein that is structurally related to the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor. Embo J. 1995;14:3654–3663. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubois S, Mariner J, Waldmann TA, Tagaya Y. IL-15Ralpha recycles and presents IL-15 In trans to neighboring cells. Immunity. 2002;17:537–547. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burkett PR, Koka R, Chien M, Chai S, Boone DL, Ma A. Coordinate expression and trans presentation of interleukin (IL)-15Ralpha and IL-15 supports natural killer cell and memory CD8+ T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:825–834. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarkowski M, Ferraris L, Martone S, Strambio de Castillia F, Misciagna D, Mazzucchelli RI, et al. Expression of interleukin-15 and interleukin-15Ralpha in monocytes of HIV type 1-infected patients with different courses of disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28:693–701. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steel JC, Waldmann TA, Morris JC. Interleukin-15 biology and its therapeutic implications in cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conlon KMJ, Janik J, Stewart D, Rosenberg SA, Worthy T, Fojo T, Fleisher T, Lugliy E, Perera L, Jaffe E, Lane HC, Snellery M, Creekmore S, Goldman C, Bryant B, Decker J, Waldmann TA. Phase I study of intravenous recombinant human interleukin-15 (rh IL-15) in adults with metastatic malignant melanoma and renal cell carcinoma [abstract] J Immunother. 2012;35:102–103. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waitz R, Solomon SB, Petre EN, Trumble AE, Fasso M, Norton L, et al. Potent induction of tumor immunity by combining tumor cryoablation with anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Cancer Res. 2012;72:430–439. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu P, Steel JC, Zhang M, Morris JC, Waldmann TA. Simultaneous blockade of multiple immune system inhibitory checkpoints enhances antitumor activity mediated by interleukin-15 in a murine metastatic colon carcinoma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6019–6028. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M, Yao Z, Dubois S, Ju W, Muller JR, Waldmann TA. Interleukin-15 combined with an anti-CD40 antibody provides enhanced therapeutic efficacy for murine models of colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7513–7518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902637106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolibab K, Yang A, Derrick SC, Waldmann TA, Perera LP, Morris SL. Highly persistent and effective prime/boost regimens against tuberculosis that use a multivalent modified vaccine virus Ankara-based tuberculosis vaccine with interleukin-15 as a molecular adjuvant. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:793–801. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00006-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perera PY, Derrick SC, Kolibab K, Momoi F, Yamamoto M, Morris SL, et al. A multi-valent vaccinia virus-based tuberculosis vaccine molecularly adjuvanted with interleukin-15 induces robust immune responses in mice. Vaccine. 2009;27:2121–2127. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sui Y, Zhu Q, Gagnon S, Dzutsev A, Terabe M, Vaccari M, et al. Innate and adaptive immune correlates of vaccine and adjuvant-induced control of mucosal transmission of SIV in macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9843–9848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911932107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraynyak KA, Kutzler MA, Cisper NJ, Laddy DJ, Morrow MP, Waldmann TA, et al. Plasmid-encoded interleukin-15 receptor alpha enhances specific immune responses induced by a DNA vaccine in vivo. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:1143–1156. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steel JC, Ramlogan CA, Yu P, Sakai Y, Forni G, Waldmann TA, et al. Interleukin-15 and its receptor augment dendritic cell vaccination against the neu oncogene through the induction of antibodies partially independent of CD4 help. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1072–1081. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoklasek TA, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L. Combined IL-15/IL-15Ralpha immunotherapy maximizes IL-15 activity in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:6072–6080. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valentin A, von Gegerfelt A, Rosati M, Miteloudis G, Alicea C, Bergamaschi C, et al. Repeated DNA therapeutic vaccination of chronically SIV-infected macaques provides additional virological benefit. Vaccine. 2010;28:1962–1974. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergamaschi C, Bear J, Rosati M, Beach RK, Alicea C, Sowder R, et al. Circulating IL-15 exists as heterodimeric complex with soluble IL-15Ralpha in human and mouse serum. Blood. 2012;120:e1–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergamaschi C, Rosati M, Jalah R, Valentin A, Kulkarni V, Alicea C, et al. Intracellular interaction of interleukin-15 with its receptor alpha during production leads to mutual stabilization and increased bioactivity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4189–4199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705725200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandau MM, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L, Jameson SC. Cutting edge: transpresentation of IL-15 by bone marrow-derived cells necessitates expression of IL-15 and IL-15R alpha by the same cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:6537–6541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stonier SW, Schluns KS. Trans-presentation: a novel mechanism regulating IL-15 delivery and responses. Immunol Lett. 2010;127:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hazama S, Noma T, Wang F, Iizuka N, Ogura Y, Yoshimura K, et al. Tumour cells engineered to secrete interleukin-15 augment anti-tumour immune responses in vivo. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:1420–1426. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He X, Li W, Wang Y, Hou L, Zhu L. Inhibition of colon tumor growth by IL-15 immunogene therapy. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:96–102. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2011.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meazza R, Lollini PL, Nanni P, De Giovanni C, Gaggero A, Comes A, et al. Gene transfer of a secretable form of IL-15 in murine adenocarcinoma cells: effects on tumorigenicity, metastatic potential and immune response. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:574–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tasaki K, Yoshida Y, Miyauchi M, Maeda T, Takenaga K, Kouzu T, et al. Transduction of murine colon carcinoma cells with interleukin-15 gene induces antitumor effects in immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7:255–261. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dubois S, Patel HJ, Zhang M, Waldmann TA, Muller JR. Preassociation of IL-15 with IL-15R alpha-IgG1-Fc enhances its activity on proliferation of NK and CD8+/CD44high T cells and its antitumor action. J Immunol. 2008;180:2099–2106. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melchionda F, Fry TJ, Milliron MJ, McKirdy MA, Tagaya Y, Mackall CL. Adjuvant IL-7 or IL-15 overcomes immunodominance and improves survival of the CD8+ memory cell pool. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1177–1187. doi: 10.1172/JCI23134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nanni P, Pupa SM, Nicoletti G, De Giovanni C, Landuzzi L, Rossi I, et al. p185(neu) protein is required for tumor and anchorage-independent growth, not for cell proliferation of transgenic mammary carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rovero S, Amici A, Di Carlo E, Bei R, Nanni P, Quaglino E, et al. DNA vaccination against rat her-2/Neu p185 more effectively inhibits carcinogenesis than transplantable carcinomas in transgenic BALB/c mice. J Immunol. 2000;165:5133–5142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ng P, Parks RJ, Cummings DT, Evelegh CM, Graham FL. An enhanced system for construction of adenoviral vectors by the two-plasmid rescue method. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:693–699. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fasso M, Waitz R, Hou Y, Rim T, Greenberg NM, Shastri N, et al. SPAS-1 (stimulator of prostatic adenocarcinoma-specific T cells)/SH3GLB2: A prostate tumor antigen identified by CTLA-4 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3509–3514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712269105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosato A, Dalla Santa S, Zoso A, Giacomelli S, Milan G, Macino B, et al. The cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response against a poorly immunogenic mammary adenocarcinoma is focused on a single immunodominant class I epitope derived from the gp70 Env product of an endogenous retrovirus. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2158–2163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nava-Parada P, Forni G, Knutson KL, Pease LR, Celis E. Peptide vaccine given with a Toll-like receptor agonist is effective for the treatment and prevention of spontaneous breast tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1326–1334. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schirmbeck R, Reimann J, Kochanek S, Kreppel F. The immunogenicity of adenovirus vectors limits the multispecificity of CD8 T-cell responses to vector-encoded transgenic antigens. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1609–1616. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soman G, Yang X, Jiang H, Giardina S, Vyas V, Mitra G, et al. MTS dye based colorimetric CTLL-2 cell proliferation assay for product release and stability monitoring of interleukin-15: assay qualification, standardization and statistical analysis. J Immunol Methods. 2009;348:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]