Abstract

Facebook advertisements were utilized to recruit nulliparous women in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy for an online survey about their childbirth preferences. A campaign of ads was targeted to women, aged 18-44, residing in the United States. The ads were viewed 10,577,381 times by 7,248,985 unique Facebook users over 18 weeks in 2011. The ad campaign yielded 6,094 clicks by 5,963 unique users at a mean cost of $0.63 per click and a unique click-through rate of 0.08%. Of those who clicked through to the study site, eighteen percent (18%, n = 1,075) consented to participate. The participant pool was reduced to 344 women after application of strict eligibility criteria. Participants represented 43 states and the District of Columbia, their mean age was 20.9 years (Mdn 19.0, SD 4.0), and their mean weeks’ gestation was 11.5 (SD 5.8). The campaign cost was $3,821.81 or $11.11 per eligible participant.

Keywords: maternal and child health, media, quantitative methods, recruitment social media, research design, research subject

Introduction

Research can be limited by the ability to access populations of interest. In the US, early gestation often is treated as a private matter until the threat of spontaneous abortion diminishes at the end of the first trimester. As such, women in early pregnancy are a difficult-to-reach study population, particularly on a national scale. Recruitment innovations are needed to access such populations in a timesaving and inexpensive manner. The purpose of this study was to identify the childbirth preferences of nulliparous women in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy; the findings of the study are published elsewhere (Arcia, 2013). The purpose of this brief report is to describe the method by which a national sample of such women was successfully recruited.

One promising method for recruitment is the use of online advertisements (ads). Online ads compare favorably to traditional recruitment methods in terms of direct financial costs (Williams, Proetto, Casiano, & Franklin, 2012) and number of labor hours required (Battistella, Kalyan, & Prior, 2010). A drawback to online recruitment is the “digital divide”—the gap between those with Internet access and those without—because it can be an obstacle to obtaining a socially, geographically, and economically diverse sample. However, the digital divide is narrowing and the narrowing trend is expected to continue. The Pew Research Center estimated that 78% of all adults in the US (94% of those aged 18-29, 87% of those aged 30-49) are Internet users and nearly two-thirds of all US adults have a home broadband connection (Zickuhr & Smith, 2012, April 13). Social networking is a very popular online activity engaged in by 50% of all US adults, 87% of US Internet users under the age of 30, and 68% of US Internet users aged 30-49 (Zickuhr & Smith, 2012, April 13). The most popular social networking website, Facebook, boasted over a billion active users worldwide by the end of 2012, more than 60% of whom used the site daily (Key Facts, 2013).

Facebook ads as recruitment tools are appealing because of their relatively low per-participant cost and the potential to target ads to the users most likely to be interested in and eligible for the advertised study. A handful of studies have used Facebook advertisements as one of a variety of recruitment strategies (Ahmed, Jacob, Allen, & Benowitz, 2011; Battistella et al., 2010; Jones & Magee, 2011; Richiardi, Pivetta, & Merletti, 2012; Ryan & Xenos, 2011; Williams et al., 2012). There exist few published reports of samples recruited exclusively via this method (Fenner et al., 2012; Lord, Brevard, & Budman, 2011; Ramo & Prochaska, 2012). Fenner and colleagues (2012) used targeted Facebook ads to recruit a demographically representative sample of 551 young women in Victoria, Australia during 2010 at a cost of $20.14 per compliant participant. Ramo & Prochaska (2012) ran targeted Facebook ads for 13 months in 2010 and 2011 to recruit 1,548 young American smokers at a cost of $4.28 per completed survey.

Methods

Sample

Inclusion in this study was limited to nulliparous women aged 18-44, living in the US who, at the time of participation, were pregnant at 20 or fewer weeks’ gestation, had not had any prior pregnancies beyond 13 weeks’ gestation, and who consented to participate. Inclusion criteria were assessed by self-report. Additional implied inclusion criteria were that participants had access to the Internet and could read and understand English as the survey was not offered in other languages. The required sample size, based on the planned statistical analyses, was 200 to 250 adequate surveys. Adequacy was defined as the completion of at least 10 of the items to be used in factor analysis. Total enrollment beyond 250 was permitted, a priori, in order to account for inadequately complete surveys.

Procedures

The investigator used Facebook’s self-service application to create 14 ads, each accompanied by a different image but with identical copy: “Pregnant? First Baby? Fill out a 15-20 minute survey today and you’ll have a 1-in-50 chance of winning a baby gift!” Clicking on the ad led users to the study survey welcome page (see Supplementary Figure 1 for the Study Procedure Flowchart). Ad images included both stock photos and family photos of persons known to the investigator. Signed photo releases were obtained for the latter group. Ad copy and images adhered to Facebook guidelines. Ads were targeted such that they appeared only on the Facebook pages of women, aged 18-44, residing in the US. The investigator opted for the cost-per-click (CPC) payment method. In the CPC model, the buyer pays only when users click on the ads whereas in the cost-per-thousand-impressions (CPM) model cost is based upon the number of times (in thousands) that the ad appears on users’ screens (Campaign Cost and Budgeting, 2012). Ads in the CPC model enter into an automated auction in which they are selected to appear on users’ screens depending upon 1) how many other ads are competing for the same target audience, 2) the maximum per-click bid (e.g., $1.10) specified by the ad buyer, and 3) how well the ad has performed in the past compared to other ads within that advertiser’s campaign. Within the CPC framework, advertisers are charged the minimum amount needed to show an ad such that clicks generally cost less than the maximum bid.

Within individual campaigns, Facebook’s ad selection algorithm heavily favors the ads that generate the most clicks. The investigator anticipated that ads featuring ethnically diverse individuals were at risk of being extinguished by the algorithm if they generated fewer clicks than ads featuring Whites. To circumvent this problem, the investigator created two separate campaigns: one featured images of light-skinned babies and pregnant women and the other featured images of dark-skinned babies and pregnant women. This dual-campaign strategy guaranteed diversity in the ad images shown.

Ethical Considerations

The University of Miami IRB approved the procedures. The study was hosted separately from Facebook on SurveyMonkey; no identifying information was collected from individuals who clicked on ads. All study data were collected anonymously. E-mail addresses collected for delivery of incentives were kept confidential and deleted upon completion of incentive delivery. E-mail addresses could not be linked to survey responses because they were collected in a separate database.

Results

Recruitment

The Facebook ads ran from March 16, 2011 until July 22, 2011. According to data provided by the Facebook self-service ad management application, the ads were shown a total of 10,577,381 times to 7,248,985 different Facebook users over the 18-week campaign period for a mean of 1.46 impressions per unique user. The ads received 6,094 clicks by 5,963 unique users for a total click-through rate of 0.06% and a unique click-through rate of 0.08% at a mean cost of $0.63 per click. The success of the ads, as measured by clicks and click-through rate, varied substantially depending upon the image. See Supplementary Table 1 for a breakdown of numbers of unique viewers, numbers of unique clicks, and the unique click-through rate of each ad image. The total number of clicks per day ranged from 10 to 70 and averaged 48.4. Cost-per-click ranged from $0.15 to $0.94. Cost per day ranged from $6.84 to $43.63 and averaged $30.33. The total cost of the Facebook ads was $3,821.81 ($11.11 per eligible participant; $16.52 per adequate survey).

Respondents

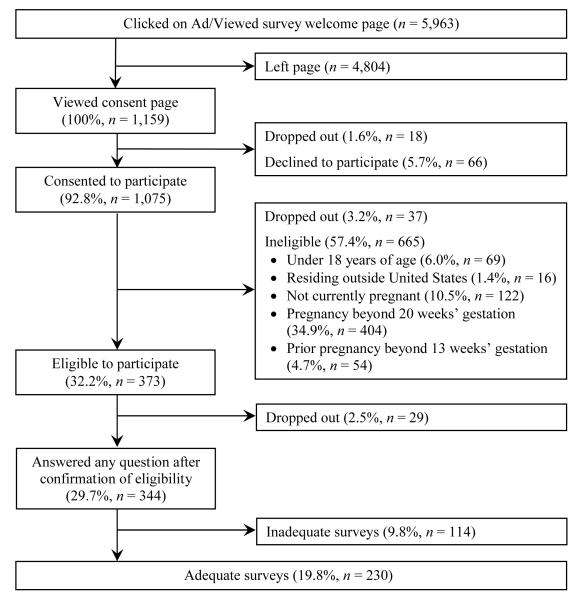

Based upon the number of unique Facebook users who clicked on study ads, 5,963 people viewed the survey welcome page. As shown in the flow diagram in Figure 1, the consent page was viewed by 1,159 people, 92.8% (n = 1,075) of whom agreed to participate but more than half whom were excluded for ineligibility. Dropout began during eligibility screening and continued over the course of the survey, such that items toward the end of the survey (e.g., most demographics) had the fewest responses. Because of dropout and the option to leave any item blank, the number of respondents varied by question. The maximum number of respondents was 344 women; 230 surveys were complete enough to be deemed adequate for the planned statistical analyses.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant inclusion, exclusion, and dropout. The denominator for the percentages is the number of individuals who viewed the consent page (n = 1,159).

Participant Characteristics

The participants’ (N = 344) mean age was 20.9 years (Mdn 19.0, SD 4.0) and their mean weeks’ gestation was 11.5 (SD 5.8). Participants aged 18 and 19 made up 52% of the sample; just 12.5% of participants were 25 or older (see Table 1). Only those participants who reached the end of the survey completed additional demographic items, the results of which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ Age, Prenatal Care Attendance, Ethnicity, Race, Marital Status, Education, Household Income, and Employment Status

| Characteristic | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (n = 344) | ||

| 18 | 89 | (25.9) |

| 19 | 90 | (26.1) |

| 20 | 51 | (14.8) |

| 21 | 25 | (7.3) |

| 22-24 | 46 | (13.4) |

| 25-34 | 39 | (11.3) |

| 35-40 | 4 | (1.2) |

| Number of prenatal care visits (n = 290) | ||

| None | 39 | (13.4) |

| One or more | 251 | (86.6) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity (n = 154) | ||

| No | 138 | (89.6) |

| Yes | 16 | (10.4) |

| Racea (n = 146) | ||

| American Indian / Alaska Native | 3 | (2.1) |

| Asian | 5 | (3.4) |

| Black / African American | 25 | (17.1) |

| Multiracial | 9 | (6.2) |

| White | 104 | (71.2) |

| Marital Status (n = 155) | ||

| Single, never married | 58 | (37.4) |

| Living with partner | 54 | (34.8) |

| Married | 36 | (23.2) |

| Separated | 2 | (1.3) |

| Divorced | 5 | (3.2) |

| Education (n = 155) | ||

| Some high school | 24 | (15.5) |

| High school diploma or GED | 58 | (37.4) |

| Some college but no degree | 51 | (32.9) |

| Associate's degree | 9 | (5.8) |

| Bachelor's degree | 9 | (5.8) |

| Graduate degree | 4 | (2.6) |

| Employment Statusa (n = 147) | ||

| Work full time | 24 | (16.3) |

| Work part time | 26 | (17.7) |

| Self-employed | 8 | (5.4) |

| Not employed, looking for work | 46 | (31.3) |

| Not employed, not looking for work | 13 | (8.8) |

| Retired | 2 | (1.4) |

| Student | 42 | (28.6) |

| Homemaker | 14 | (9.5) |

| Annual Household Income (n = 131) | ||

| Less than $15,000 | 71 | (54.2) |

| $15,000 to $24,999 | 18 | (13.7) |

| $25,000 to $34,999 | 11 | (8.4) |

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 13 | (9.9) |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 9 | (6.9) |

| $75,000 to $99,999 | 4 | (3.1) |

| $100,000 to $124,999 | 3 | (2.3) |

| $125,000 or more | 2 | (1.5) |

Percentages sum to more than 100% because participants were able to select more than one response option.

All participants reported their state of residence during eligibility screening. The sample represented 43 states and DC; only Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Rhode Island, and South Dakota were not represented. At the end of the survey, some participants (n = 158) provided their home zip codes that in turn, were used to generate the map in Supplementary Figure 2.

Discussion

Women in early pregnancy are difficult to reach as a research population in that they may have disclosed their pregnancy to few other people. Facebook ads allowed for the collection of enough adequate surveys from eligible women to satisfy the sample size requirements of the study. Given that study participants were widely distributed geographically and 13.4% of them had not yet accessed prenatal care, it is unlikely that a similar sample could have been recruited using traditional methods, even at much higher cost.

The total click-through rate for this study (0.06%) was higher than the range of total click-through rates (0.02% - 0.05%) reported by others who used this method (Fenner et al., 2012; Lord et al, 2011; Ramo & Prochaska, 2012; Richiardi et al., 2012). Of these studies, only Fenner and colleagues (2012) reported a unique click-through rate, which at 1.69% is dramatically higher than the 0.08% achieved in this study and may be explained, in part, by the much lower number of unique users exposed to ads (469,678 vs. 7,248,985) and thus, the much higher number of impressions per unique user (76.98 vs. 1.46).

The principal limitation of the recruitment method is that the population of Facebook users is not fully representative of the US population. Investigators can mitigate this limitation by engaging in purposive sampling and aiming ads at specific groups through targeting settings (e.g., age), language (e.g., Spanish), or culturally-specific images. Facebook provides extremely little demographic data about the users who are exposed to or interact with ads, or even about its general user population. Facebook ads are akin to print newspaper ads in that they are a form of passive advertising. As with newspaper ads, investigators have limited ability to assess the magnitude of any differential response bias because so little is known about non-respondents.

In this study, the high proportion of Facebook users aged 18-24 who were exposed to the ads (81.4%) was exceeded by the proportion in that age group (87.5%) who participated. As a result, the mean and median ages of participants (20.9 and 19.0 respectively) were substantially lower than the mean age of US mothers at first birth (25.4) (Martin et al., 2012). One can only speculate as to the cause of the age bias. Perhaps younger users spend more time using Facebook and/or are more likely to attend to and click on ads than older users. Alternatively, the baby gift incentive or the ad design may have been more appealing to younger users. Facebook provided some aggregate metrics of click-through-rates by state but only as percentages on a per-campaign, per-month basis making it impossible to accurately evaluate geographic bias for the study as a whole. Hispanics were underrepresented in this study but because ethnicity and other important demographics were available for less than 50% of respondents, one cannot determine how much of that underrepresentation is attributable to the recruitment method and how much to differential rates of dropout. The incompleteness of the demographic data is a limitation of this study.

Budget and campaign duration projections are difficult because ad performance depends upon numerous factors including ad appeal, the size of the target population, and the amount of competition from other advertisers. Ad costs are likely to increase over time. Ramo and Prochaska (2012) completed their recruitment at around the time that recruitment began for this study and they reported a lower cost-per-click ($0.45 vs. $0.63). Ad performance and budget can be monitored on a daily basis so that adjustments can be made in real time to meet the recruitment needs of the study. Investigators should be aware that the design and advertising policies of Facebook are subject to change with little or no notice. Often, changes bring useful new features, but flexibility may be needed to adapt to modifications in permissible ad content and format. These drawbacks may be outweighed by the fact that ad creation and maintenance require minimal time or technical expertise.

It is tempting to tailor research to readily available populations, such as individuals who have already sought treatment for a condition. Online ads broaden possibilities for recruitment of individuals who are, for example, experiencing troublesome health symptoms but who have not sought professional assistance. As shown by Lord and colleagues (2011), who studied opioid misuse, this recruitment strategy is useful even for behaviors and conditions around which there exists social stigma and secrecy. There is additional recruitment and data collection potential through the use of other features of Facebook and through other social media platforms. Social-behavioral scientists have a great deal to gain by harnessing the power of these new social media tools.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Study Procedure Flowchart. All items after confirmation of eligibility included the response option “Prefer not to answer” or were optional.

Supplementary Figure 2. Map of participant zip codes. One marker in Alaska was omitted in order to show greater detail.

Supplementary Table 1 Ad Images, Unique Ad Viewers, Number of Unique Clicks, and Unique Click-Through Rate (CTR)

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the Beta Tau Chapter of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, and the Florida Nurses Foundation. Postdoctoral Fellowship supported by Reducing Health Disparities through Informatics (T32 NR007969).

Footnotes

This article is based on data collected as part of a doctoral dissertation conducted at the University of Miami. A related manuscript entitled “US nulliparas’ perceptions of roles and of the birth experience as predictors of their childbirth preferences” has been published in the journal Midwifery.

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Arcia A. US Nulliparas’ perceptions of roles and of the birth experience as predictors of their childbirth preferences. Midwifery. 2013;29:885–894. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.10.002. doi:10.106/j.midw.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed B, Jacob P, Allen F, Benowitz N. Attitudes and practices of hookah smokers in the San Francisco Bay Area. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(2):146–152. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.587707. doi:10.1080/02791072.2011.587707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistella E, Kalyan S, Prior JC. Evaluation methods and costs associated with recruiting healthy women volunteers to a study of ovulation. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19(8):1519–1524. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1751. doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campaign Cost and Budgeting 2012 Retrieved from: http://www.facebook.com/help/?page=864.

- Fenner Y, Garland SZ, Moore EE, Jayasinghe Y, Fletcher A, Tabrizi S, Wark JD. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: An exploratory study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012;14(1):e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1978. doi:10.2196/jmir.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key Facts 2013 Retrieved from http://newsroom.fb.com/content/default.aspx?NewsAreaId=22.

- Jones SC, Magee CA. Exposure to alcohol advertising and alcohol consumption among Australian adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2011;46(5):630–637. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr080. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agr080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord S, Brevard J, Budman S. Connecting to young adults: An online social network survey of beliefs and attitudes associated with prescription opioid misuse among college students. Substance Use & Misuse. 2011;46:66–76. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521371. doi:10.3109/10826084.2011.521371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJK, Wilson EC, Mathews TJ. National vital statistics reports. 1. Vol. 61. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyatsville, MD: 2012. Births: Final data for 2010. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_01.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Prochaska JJ. Broad reach and targeted recruitment using Facebook for an online survey of young adult substance use. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012;14(1):e28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1878. doi:10.2196/jmir.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richiardi L, Pivetta E, Merletti F. Recruiting study participants through Facebook. Epidemiology. 2012;23(1):175. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823b5ee4. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823b5ee4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T, Xenos S. Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the Big Five, shyness, narcissism, loneliness, and Facebook usage. Computers in Human Behavior. 2011;27(5):1658–1664. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2011.02.004. [Google Scholar]

- Williams MT, Proetto D, Casiano D, Franklin ME. Recruitment of a hidden population: African Americans with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2012;33:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.09.001. doi:10.1016/j.cct2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickuhr K, Smith A. Digital differences. 2012 Apr 13; Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Digital_differences_041310.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Study Procedure Flowchart. All items after confirmation of eligibility included the response option “Prefer not to answer” or were optional.

Supplementary Figure 2. Map of participant zip codes. One marker in Alaska was omitted in order to show greater detail.

Supplementary Table 1 Ad Images, Unique Ad Viewers, Number of Unique Clicks, and Unique Click-Through Rate (CTR)