Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to compare the effect of betahistine dihydrochloride alone and in combination with vestibular rehabilitation for the management of patients with balance disorders following head trauma.

Methods

In this preliminary clinical trial, a group of patients with head trauma was referred to our university-based tertiary care balance unit over a 1-year period. The study included 60 patients with balance disorder following head trauma. Patients were randomly divided into 3 groups with 20 patients each. The first group was treated by betahistine dihydrochloride tablets 48 mg/d alone. The second group was treated with a standard vestibular rehabilitation program. The third group was given betahistine dihydrochloride tablets (48 mg/d) in addition to the early standard vestibular rehabilitation program. Videonystagmography was used in the diagnosis, characterization, and monitoring of all patients with balance disorders, with improvement of the pretreatment objective results taken as a marker for treatment progress.

Results

Recovery time was within the first 3 months following head trauma in 57 (95%) of the patients. Recovery was faster after mild head trauma than after moderate and severe traumas. Patients who underwent vestibular rehabilitation immediately after the onset of head trauma (with or without addition of betahistine dihydrochloride) recovered earlier than those treated with betahistine dihydrochloride alone.

Conclusion

Based on these preliminary findings in a small group of patients, early vestibular rehabilitation with the concomitant use of betahistine dihydrochloride showed better results than the other 2 treatments alone in patients with balance disorders following head trauma. Early vestibular rehabilitation seemed to improve recovery that was enhanced by the use of betahistine dihydrochloride, and may have depressed the associated adverse effects such as nausea and vomiting.

Key indexing terms: Head trauma, Dizziness, Electronystagmography, Rehabilitation, Betahistine dihydrochloride

Introduction

Dizziness commonly is associated with head injury. Although vertigo is its most common type, dizziness may also include lightheadedness, disorientation, and disequilibrium.1,2 These balance disorders may take a prolonged incapacitating course that often requires management. The goal of management in such cases is to control the disabling symptoms, reduce the resulting functional disability, and improve the quality of life in patients suffering from such balance disorders.3

The current management options are restricted to pharmacological and nonpharmacological (repositioning maneuvers and vestibular rehabilitation) treatments. Multiple drugs have been described and used in the acute phase following head trauma to improve the recovery process and to facilitate vestibular compensation.4 On the other hand, rehabilitation treatments aim at abolishing the disabling symptoms and are based on either habituation or adaptation of the vestibular system or the repositioning of the provocative floating otoconial debris.

The choice of the optimum management protocol for patients who develop balance disorders following head trauma is controversial. Pharmacological therapy is used by some authors to improve the recovery process. Others feel that drugs may be counterproductive with respect to the eventual desired outcome of vestibular rehabilitation of patients especially those drugs with a vestibular suppressant action.3

Betahistine dihydrochloride has been used as an antivertigo agent for a long time, and its therapeutic effects and its safety have been shown in many controlled clinical studies in vertigo patients.3,5 A major advantage of betahistine dihydrochloride is that it has no sedative effects following its administration in animal models6 or in healthy subjects.5 Patients treated with betahistine dihydrochloride can thus maintain their lifestyle without the fear of fall.

Advocates of vestibular rehabilitation have suggested that the stimulus for recovery and promotion of central compensation is repeated exposure to the sensory conflicts produced by the head movements, thus recommending early vestibular rehabilitation to promote vestibular compensation.7,8 This is contradicted, however, by those who recommend that vestibular rehabilitation is to be adopted when patients have failed to compensate after 2 to 3 months9 or have failed to respond to pharmacological treatment.3

The purpose of this preliminary clinical study was to compare the clinical outcomes and recovery time in 3 groups of patients: those who received only betahistine dihydrochloride treatment, those who received only early vestibular rehabilitation treatment, and those who received a combination of both treatments.

Methods

Patients

In this prospective study, we used a group of head trauma cases referred to our university-based tertiary care balance unit over a 1-year period. The study included 60 patients with balance disorder following head trauma. All patients signed an appropriate consent forms. The study was registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT2013082814503N1) and was approved by the Research and Ethics Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Suez Canal University, Ismailia, Egypt.

Patients with unstable cervical injuries or other serious injuries, unable to ambulate, or whose condition was thought to be aggravated by vestibular testing were excluded from the study for the patients’ safety. Included patients had no previous complaints of balance disorders of otologic or other cause and had taken no sedating drugs or tranquilizers.

Head trauma was classified following the Glasgow coma scale into severe (Glasgow coma scale ≤ 8), moderate (9-12), and mild (13-15).

Evaluation

Each patient in the study underwent detailed otolaryngological history taking, thorough otolaryngological clinical examination; standard neurological examination; and computed tomography scanning of the neck, skull, and brain.

Videonystagmography

Diagnosis, characterization, and monitoring of balance disorders were done using videonystagmography (videonystagmography computerized analyzer; ICS, Schaumburg, IL). Videonystagmography records the eye movements using digital video image technology, utilizing infrared illumination to determine eye position. It enables both subjective observation of eye movements together with objective collection and analysis of eye movement waveforms via computer algorithm that can be saved for later reference and comparison. Videonystagmography analysis for each patient was done within 24 hours of the head trauma and at 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, and then every month until recovery.

Repetition of videonystagmography testing depended on the persistence of subjective dizziness, objective abnormal videonystagmographic findings, and clinically detected nystagmus. The videonystagmography test battery consisted of 3 groups of tests performed in a systematic fashion and in the same chronological order to assess the oculomotor and vestibular systems as well as their interaction. The first group of tests investigated visual oculomotor functions and evaluated central (nonvestibular) eye movements. The second group of tests recorded abnormal eye movements in relation to altered head position. The third group of tests assessed vestibule-oculomotor function by means of a bithermal caloric test to detect peripheral labyrinthine dysfunction.

In case any of the patients was unable to tolerate the test any further, he or she was allowed to rest for 2 hours before resuming the test protocol.

Videonystagmography normative data were obtained from preprogrammed software within the system itself. Criteria of defining peripheral, central, and mixed vestibular lesions were determined as described previously.10

Study Design

Patients with a diagnosed balance disorder were randomly divided into 3 treatment groups with 20 patients each, putting into consideration the inclusion criteria of selection.

The first group was treated by betahistine dihydrochloride tablets 48 mg/d.

The second group was treated with a standard vestibular rehabilitation program based on the work of Shepard and Telian.11 Each patient received an individualized program that included habituation exercises (to facilitate central nervous system compensation by negating pathological responses to head movement), postural control exercises, and general conditioning activities. These exercises were conducted in the physiotherapy department and were performed in an open-air area twice a day, 6 days a week, with a rest on the seventh day. Vestibular rehabilitation of cases diagnosed as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo was done by the Epley canalith repositioning maneuver.12

The third group was given betahistine dihydrochloride (48 mg/d) in addition to the standard vestibular rehabilitation program following the same protocol as in the second group.

Statistical Analysis

Videonystagmography results of objective testing and abnormalities after therapy were recorded for each group. Data were analyzed using analysis of variance. Posttreatment significant results of the 3 groups were tested and compared by post hoc least significant difference. Differences were considered significant with a P value ≤ .05.

Results

The study included 60 patients: 43 men and 17 women (Fig 1). Their ages ranged from 20 to 50 years. Patients with an age range of 20 to 30 years were 24 (40%). Age ranges from 31 to 40 years were 21 (35%) patients and from 41 to 50 years were 15 (25%) patients. The mean age was 30 years.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Group I (treated by betahistine dihydrochloride) and group II (receiving a standard vestibular rehabilitation program) included 14 men and 6 women each. Group III (receiving betahistine dihydrochloride in addition to the standard vestibular rehabilitation program) included 15 men and 5 women.

All the patients completed the study with no dropouts. In group II that started early vestibular rehabilitation, nausea and even vomiting were common symptoms during the treatment especially during the first week and significantly decreased later on. In this particular group, 8 (40%) patients were given an antiemetic (ondansetron 8 mg/d) to ameliorate their symptoms so as to be able to carry on with their treatment protocol.

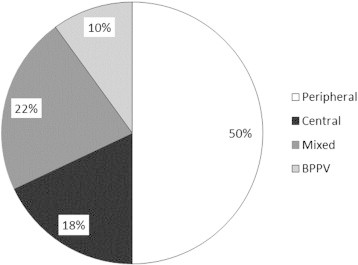

Balance disorders were characterized by videonystagmography into the following: peripheral vestibular in 30 (50%) cases, central vestibular in 11 (18%), mixed vestibular in 13 (22%), and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in 6 (10%) (Fig 2). Table 1 shows the distribution of the vestibular lesions among the study groups.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of the balance disorders in 60 patients.

Table 1.

Distribution of the Vestibular Lesions Among the Study Groups

| Lesion/Treatment | Betahistine | Rehabilitation | Rehabilitation + Betahistine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral | 11 | 9 | 9 |

| Central | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mixed | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | – | 3 | 3 |

Following the Glasgow coma scale, head trauma was classified into mild in 22 (37%) cases, moderate in 23 (38%) cases, and severe in 15 (25%) cases. Table 2 shows the distribution of the degree of head trauma among the study cohorts.

Table 2.

Distribution of the Degree of Head Trauma Among the Study Groups

| Trauma/Treatment | Betahistine | Rehabilitation | Rehabilitation + Betahistine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| Moderate | 7 | 8 | 8 |

| Severe | 5 | 4 | 6 |

In all groups, recovery of balance disorders did not occur before the second week following head injury regardless of the adopted treatment protocol. Complete recovery was judged by the absence of subjective symptoms of balance disorders, the absence of clinically detected nystagmus, and the objective return of videonystagmography test values to the normal reference range.

In general, there were no significant differences between the type of vestibular lesion and the duration of recovery in all the 3 groups. However, the duration of recovery was significantly less in mild head trauma patients compared to those subjected to moderate and severe trauma (P< .05). Table 3 shows the duration of recovery in relation to the severity of head trauma.

Table 3.

Duration of Recovery in Relation to the Severity of Head Trauma

| Duration/Severity | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15-30 d | 14 (64%) | 8 (35%) | – |

| 31-60 d | 6 (27%) | 13 (56%) | 8 (53%) |

| 61-90 d | 2 (9%) | 2 (9%) | 4 (27%) |

| > 90 d | – | – | 3 (20%) |

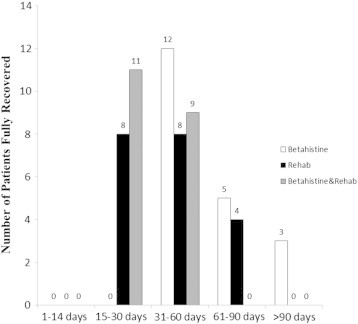

The group receiving an early vestibular rehabilitation treatment with a concomitant betahistine therapy was the earliest to recover. It showed complete recovery within the first 2 months. In the group receiving only an early vestibular rehabilitation, 80% of the patients recovered within the first 2 months and 20% recovered by the third month. In the group receiving only betahistine dihydrochloride, 85% of the patients recovered by the second and third months, whereas the rest of the patients showed a delayed recovery beyond the third month following the initial head trauma. The mean duration of recovery in patients who only received betahistine was 62.1 days (SD 20.8 days). That was significantly (P< .05) longer than in patients who only received early vestibular rehabilitation, 37.6 days (SD 18.2 days), or those who received both treatments, 34.4 days (SD 14.0 days). Addition of betahistine dihydrochloride to the early vestibular rehabilitation treatment did not significantly improve the mean recovery duration when compared to the early vestibular rehabilitation alone. Full recovery time after each form of treatment is shown in Fig 3.

Fig 3.

Recovery vs treatment strategy.

One third of the 6 patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (2 cases) showed an early recovery within the first month. They were treated with the Epley maneuver in addition to betahistine dihydrochloride. Another third (2 cases) treated with Epley maneuver alone recovered within the second month.

Delayed recovery to the third month following head trauma was seen in one third of the cases (2 cases). One of these cases was treated with the Epley maneuver with betahistine dihydrochloride, and the other case was treated with the Epley maneuver alone.

Discussion

Adopting an optimum management protocol for patients who develop balance disorders following head trauma is controversial. In this preliminary study, we show that patients who underwent early vestibular rehabilitation treatment with a concomitant betahistine dihydrochloride therapy were the earliest to recover. They showed complete recovery within the first 2 months. We also show that early vestibular rehabilitation showed a statistically significant result in speeding recovery from balance disorders following head trauma when compared to treatment with betahistine dihydrochloride alone.

The rationale for adopting early vestibular exercises originated from the observation that patients with balance disorders who were active recovered faster.

Habituation and adaptation are 2 main concepts in vestibular rehabilitation exercises. Habituation exercises are based on the idea that repeated exposure to a provocative stimulus will result in a reduction of the symptomatic responses to that stimulus.6,13 With time, the patient should be able to perform the same provoking movements with a progressive tolerance. Adaptation exercises initiate the central nervous system to modify the gain of the vestibular system.

Our protocol for early vestibular rehabilitation treatment was effective in peripheral, central, and mixed vestibular lesions as per the videonystagmography characterization of patients with balance disorders encountered in this study. All cases showed complete recovery, with peripheral vestibular lesions showing a trend to recover faster than mixed and central lesions. Recovery was significantly faster in mild head trauma vs moderate and severe traumas.

Some authors recommend the delay of vestibular rehabilitation 2 to 3 months after head trauma, having a feeling that balance disorder will resolve with time through natural compensation. It is estimated that spontaneous recovery time for the symptoms following mild head injury is 3 to 9 months in most individuals, with a persistence of symptoms for greater than 1 year in 10% to 15% of the patients.7,14 Our data show that all patients receiving early vestibular rehabilitation treatment (with or without the concomitant use of betahistine dihydrochloride) recovered within the first 3 months following head trauma. There was an early reduction of self-perceived imbalance provoked by head movements that was objectively monitored, followed, and documented by videonystagmography. These data stand for our commendation that early vestibular rehabilitation following head trauma shortens the disability time and speeds recovery.

One drawback we experienced with early vestibular rehabilitation regimen (without the concomitant use of betahistine dihydrochloride) was the vigorous reactive response in the form of nausea and vomiting in the first week of treatment that significantly dropped later on. Without the use of an antiemetic, it was hard for the patients to perform the early rehabilitation program. Ondansetron is a serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. We used this drug for its antiemetic effect and because it has been shown not to impair the capacity for central compensation.15

The 6 patients diagnosed as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo were treated with the Epley maneuver with or without betahistine dihydrochloride. Epley canalith repositioning maneuver (a special form of vestibular rehabilitation exercise specific for such cases) is suggested to be effective by moving the exciting otolithic debris away from the peripheral vestibular end organs.

There was no statistical difference in recovery time between the treatment with the Epley maneuver alone and after the addition of betahistine dihydrochloride, as has been previously shown in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.16 This is perhaps attributed to the small number of our series of patients.

On the other hand, betahistine dihydrochloride is a histamine analogue. Being a potent H3 receptor antagonist, it promotes and facilitates central vestibular compensation. It has also been suggested that it acts by improving the blood circulation of the inner ear and facilitates histamine release both in the brain as well in peripheral labyrinthine receptors.3 The clinical efficacy of betahistine dihydrochloride has been established by several controlled clinical studies in vestibular patients over the past years.3-6,17 Betahistine was also shown to decrease the incidence of nausea and vomiting.4 This might explain the fact that the group of patients under betahistine dihydrochloride treatment experienced less nausea and vomiting compared to those treated with vestibular rehabilitation therapy only.

However, electrophysiological studies have shown that the clinical action of betahistine dihydrochloride is most probably produced by an inhibitory influence exerted at the vestibular nuclei and at the peripheral end organs.18 This inhibitory action that modulates the afferent sensory input and reestablishes the bilateral balance of activity in the afferent neurons18 might well be the cause for the relative delay in recovery seen in this group of patients when compared to the group of patients treated with early vestibular rehabilitation.

Study Limitations

This was a preliminary study, and the small number of our patients in each group might have obviated any statistical significance that would have been apparent with higher numbers. Furthermore, the study was not a double-blind, placebo-controlled design. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study with a larger cohort is currently under preparation.

The fact that the group treated by betahistine dihydrochloride did not contain any participants with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo creates a difference between the treatment groups and could have constituted a potential bias.

Conclusion

Reviewing these preliminary findings, it appears that the concomitant use of an early vestibular rehabilitation protocol with betahistine dihydrochloride may be effective for treating patients with balance disorders following head trauma than using either treatment alone. For the patients in this study, early vestibular rehabilitation sped up recovery that was enhanced by the use of betahistine dihydrochloride, which also may have depressed the associated adverse effects such as nausea and vomiting.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest

No funding sources or conflicts of interest were reported for this study.

References

- 1.Davies R.A., Luxon L.M. Dizziness following head injury: a neuro-otologic study. N Neurol. 1995;242:222–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00919595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffer M.E., Balough B.J., Gottshall K.R. Posttraumatic balance disorders. Int Tinnitus J. 2007;13:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mira E. Improving the quality of life in patients with vestibular disorders: the role of medical treatments and physical rehabilitation. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:109–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soto E., Vega R. Neuropharmacology of vestibular system disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:26–40. doi: 10.2174/157015910790909511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacour M., van de Heyning P.A., Novotny M., Tighilet B. Betahistine in the treatment of Meniere’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(4):429–440. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Betts T., Harris D., Gadd E. The effect of two antivertigo drugs betahistine and prochlorperazine on driving skills. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;32:455–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb03930.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffer M.E., Gottshall K.R., Moore R., Balough B.J., Wester D. Characterizing and treating dizziness after mild head trauma. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:135–138. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herdman S.J., Blatt P.J., Schubert M.C. Vestibular rehabilitation of patients with vestibular hypofunction or with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Curr Opin Neurol. 2000;13:39–43. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200002000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen H.E. Disability and rehabilitation in the dizzy patient. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19:49–54. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000194373.08203.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naguib M.B., Madian Y., Refaat M., Mohsen O., El Tabakh, Abo-Setta A. Characterisation and objective monitoring of balance disorders following head trauma, using videonystagmography. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126:26–33. doi: 10.1017/S002221511100291X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepard N.T., Telian S.A. Programmatic vestibular rehabilitation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112:173–182. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epley J.M. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:399–404. doi: 10.1177/019459989210700310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cawthorne T. The physiological basis for head exercises. J Chartered Soc Physiother. 1944;30:106–107. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levin H.S., Mattis S., Ruff R.M. Neurobehavioral outcome after minor head injury. J Neurosurg. 1987;66:234–243. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.66.2.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venail F., Biboulet R., Mondain M., Uziel A. A protective effect of 5-HT3 antagonist against vestibular deficit? Metoclopramide versus ondansetron at the early stage of vestibular neuritis: a pilot study. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2012;129(2):65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavaliere M., Mottola G., Iemma M. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a study of two manoeuvres with and without betahistine. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2005;25:107–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mira E., Guidetti G., Ghilardi L. Betahistine dihydrochloride in the treatment of peripheral vestibular vertigo. Eur Arch Otolaryngol. 2003;260:73–77. doi: 10.1007/s00405-002-0524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chavez O., Vega R., Soto E. Histamine (H3) receptors modulate the excitatory amino acid receptor response of the vestibular afferent. Brain Res. 2005;1064:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]