Abstract

Introduction

In the Tessier classification, craniofacial clefts are numbered from 0 to 14 and extend along constant axes through the eyebrows, eyelids, maxilla, nostrils, and the lips. We studied a patient with bilateral cleft 10 associated with ocular abnormalities.

Method

Clinical report with orbital and cranial computed tomography.

Results

After pregnancy complicated by oligohydramnios, digoxin, and lisinopril exposure, a boy was born with facial and ocular dysmorphism. Examination at age 26 months showed bilateral epibulbar dermoids, covering half the corneal surface, and unilateral morning glory anomaly of the optic nerve. Ductions of the right eye were normal, but the left eye had severely impaired ductions in all directions, left hypotropia, and esotropia. Under anesthesia, the left eye could not be rotated freely in any direction. Bilateral Tessier cleft number 10 was implicated by the presence of colobomata of the middle third of the upper eyelids and eyebrows. As the cleft continued into the hairline, there was marked anterior scalp alopecia. Computed x-ray tomography showed a left middle cranial fossa arachnoid cyst and calcification of the reflected tendon of the superior oblique muscle, trochlea, and underlying sclera, with downward and lateral globe displacement.

Discussion

Tessier 10 clefts are very rare and usually associated with encephalocele. Bilateral 10 clefts have not been reported previously. In this case, there was coexisting unilateral morning glory anomaly and arachnoid cyst of the left middle cranial fossa but no encephalocele.

Conclusions

Bilateral Tessier facial cleft 10 may be associated with alopecia, morning glory anomaly, epibulbar dermoids, arachnoid cyst, and restrictive strabismus.

Keywords: Dermoid, facial cleft, morning glory anomaly, strabismus

Craniofacial clefts are estimated to occur between 1.43 and 4.85 per 100,000 births.1 Clefts may form owing to failure of fusion of the facial processes or to abnormalities of mesodermal migration and penetration.2 Most atypical craniofacial clefts occur sporadically. Several environmental factors have been implicated as causes of clefts: radiation, infection, maternal metabolic imbalances, and drugs. Anticonvulsivants, antimetabolic, and alkylating agents, steroids, and tranquilizers have been reported in association with the pathogenesis of cleft lip and palate.

In 1976, Tessier proposed a classification of craniofacial clefts that is now internationally accepted.3 The classification incorporates clinical description of the clefts and surgical observations of underlying bony structures. The clefts are numbered from 0 to 14 and extend along constant axes through the eyebrows or eyelids, the maxilla, the nostrils, and the lip. The clefts are described as cranial in nature when they are directed rostrally or facial in nature when they are directed caudally.

Kawamoto emphasized the importance of keeping the “time zone” concept in mind to identify all the possible combinations of facial and cranial clefts, such as 1–14, 1–13, 2–12, 3–11, and 4–10.1 Such a guided examination will disclose unexpected soft and bony tissue malformations when they are present. We report here a clinical encounter of a rare bilateral cleft number 10.

CLINICAL REPORT

A 26-month-old Hispanic boy was seen at the University of California Los Angeles Craniofacial Clinic and Jules Stein Eye Institute. He was the product of a Hispanic female, gravida 4, para 4. Maternal cardiomyopathy, oligohydramnios, and a vaginal infection of unknown cause complicated the full-term pregnancy. The fetus was exposed to metoprolol, digoxin, and nitroglycerin. There was no family history of craniofacial, genetic abnormalities, or evidence of amniotic bands. The child passed hearing screening test at birth, has normal language skills, and has normal dentition.

The child exhibited bilateral upper eyelid colobomata at the 10-and 2-o’clock positions in the right and left eyes, respectively, with the presence of bilateral lid notch. There was no midface hypoplasia or preauricular skin tag formation. Beginning in the medial third, lateral portions of the eyebrows became sprayed and sparse. Osseous cranial sutures were normal. There was alopecia on the anterior cranium, with only a small tuft of hair in the midline at the forehead level (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Left, Marked alopecia. Right, Patient’s face at 26 months. Bilateral epibulbar dermoids, marked left hypotropia, and esotropia. Bilateral lid colobomata. Absent middle third of the left eyebrow.

The child could fixate and follow a small object with his right but not left eye, which could perceive light only. There were bilateral white, elevated epibulbar dermoids incorporating half of each corneal surface. The anterior chambers of both eyes were deep and quiet, and the crystalline lenses were clear. Ocular motility examination disclosed left hypotropia and esotropia. The right eye exhibited mildly limited abduction, but left eye ductions were severely impaired in all directions, particularly abduction and supra-duction. Under general anesthesia, the left eye could not be rotated freely in any direction using forceps. Intraocular pressure was normal. Cycloplegic retinoscopy disclosed high compound hyperopic astigmatism, greater in the right than in the left eye. Right eye: + 2.25 + 6.00 axis 90 degrees, left eye + 1.00 + 3.00 axis 45 degrees. Fundus examination disclosed pigmentary changes in the nasal retina on the right eye. In the left eye, the optic nerve head was markedly enlarged, with a vacant central excavation devoid of vessels typical for morning glory anomaly. Retinal vessels in the left eye were markedly attenuated.

Follow-up examination at age 7 years showed that near visual acuity with correction was 20/40 in the right eye and light perception only in the left eye. The child had a very small area of central alopecia. There were bilateral white, elevated epibulbar dermoids covering half of each corneal surface (Fig. 2). Ocular motility remained similar to the previous examination.

FIGURE 2.

Left, Patient’s face at 7 years. Right, Bilateral epibulbar dermoids, marked left hypotropia, and esotropia. Bilateral lid colobomata. Café au lait facial pigmentation.

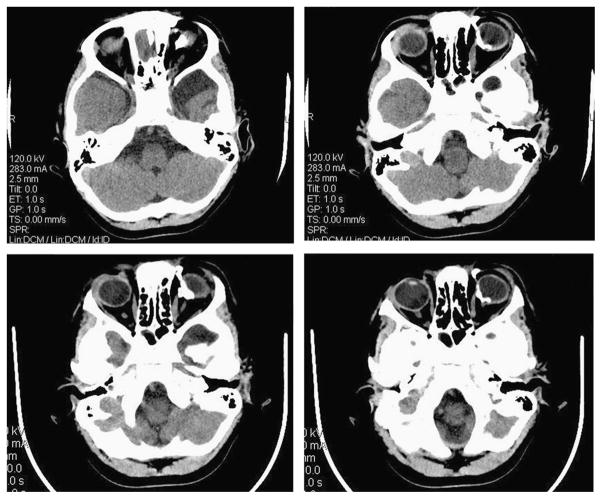

Computed x-ray tomography of the brain and orbits showed frontotemporal encephalomalacia and calcification of the reflected tendon of the left superior oblique muscle, trochlea, and underlying sclera, with downward and lateral globe displacement (Fig. 3). There were no calvarial abnormalities.

FIGURE 3.

Axial computed tomographic scans showing calcification of the reflected tendon of the left superior oblique muscle, trochlea, and underlying sclera, with downward and lateral globe displacement. An arachnoid cyst is present in the left middle cranial fossa.

DISCUSSION

The child presented a previously undescribed bilateral Tessier craniofacial cleft number 10. Kawamoto1 has explained how this cleft represents the cranial extension of cleft number 4. Fan et al4 described the largest report on the surgical management and outcome of 12 patients with Tessier number 10 clefts. Eyebrow reconstruction was performed by Fan et al in 4 patients using a frontal hairline transposition flap, with a sliding myocutaneous flap and hard palate mucosa graft to reconstruct the upper eyelid defects. Enucleation was performed in 2 adults who had corneal staphyloma, exophthalmos, and total blindness of the affected eyes.

Tessier 10 clefts are very rare and usually associated with encephalocele that was not present in this patient. Instead, our patient exhibited coexisting unilateral morning glory anomaly and arachnoid cyst of the left middle cranial fossa. An intraorbital calcified mass contributed to the restrictive strabismus and inferolateral globe displacement.

Lee and Traboulsi5 described the association of morning glory anomaly with retinal detachment and neurovascular abnormalities such as moyamoya disease. Facial and central nervous system abnormalities have also been reported, such as cleft lip and palate, hypertelorbitism, encephalocele, agenesis of the corpus callosum, and Arnold-Chiari type 1 malformation. Diabetes insipidus has been described as the most common endocrine abnormality, although plasma levels of growth hormone, prolactin, and thyroid-stimulating hormone can be abnormal.

The present case demonstrates that bilateral Tessier facial cleft number 10 may be associated with alopecia, morning glory optic disc anomaly, epibulbar dermoids, and restrictive strabismus.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Research to Prevent Blindness Walt and Lilly Disney Award.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kawamoto HK., Jr The kaleidoscopic world of rare craniofacial clefts: order out of chaos (Tessier classification) Clin Plast Surg. 1976;3:529–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Ani SA, Locke MB, Rees M, et al. Our experiences managing a rare cranio-orbital cleft. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:819–822. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31816b6c12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tessier P. Anatomical classification facial, cranio-facial and latero-facial clefts. J Maxillofac Surg. 1976;4:69–92. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(76)80013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan X, Shao C, Fu Y, et al. Surgical management and outcome of Tessier number 10 clefts. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:2290–2294. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee BJ, Traboulsi EI. Update on the morning glory disc anomaly. Ophthalmic Genet. 2008;29:47–52. doi: 10.1080/13816810801901876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]