Abstract

Background

Individuals with a strong family history of colorectal cancer (CRC) have significant risk for CRC, though adherence to colonoscopy screening in these groups remains low. This study assessed whether a tailored, telephone counseling intervention can increase adherence to colonoscopy in members of high risk families in a randomized, controlled trial.

Methods

Eligible participants were recruited from two national cancer registries if they had a first-degree relative with CRC under age 60 or multiple affected family members, which included families that met Amsterdam criteria for Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colon Cancer, and if they were due for colonoscopy within 24-months. Participants were randomized to receive a tailored, telephone intervention grounded in behavioral theory or a mailed packet with general information about screening. Colonoscopy status was assessed through follow-up surveys and endoscopy reports. Cox-proportional hazards models were used to assess intervention effect.

Results

Of the 632 participants (aged 25–80), 60% were female, the majority were White, non-Hispanic, educated and had health insurance. Colonoscopy adherence increased 11 percentage points in the tailored, telephone intervention group, compared to no significant change in the mailed group. The telephone intervention was associated with a 32% increase in screening adherence compared to the mailed intervention (Hazard Ratio=1.32; p=0.01).

Conclusions

A tailored, telephone intervention can effectively increase colonoscopy adherence in high risk persons. This intervention has the potential for broad dissemination to health-care organizations or other high risk populations.

Impact

Increasing adherence to colonoscopy among persons with increased CRC risk could effectively reduce incidence and mortality from this disease.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, colonoscopy, HNPCC, family history, randomized-controlled trial

Introduction

Though widely considered preventable, colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a common and often fatal cancer. More than 140,000 men and women in the U.S. will develop CRC each year, and 50,000 will die from this disease [1]. The lifetime risk for developing CRC is about five percent but a family history of CRC substantially increases this risk; having a first degree relative with CRC increases the risk about two-fold but if the relative has CRC under age 60 or there is more than a single first-degree relative the risk increases three to six fold [2–4]. Moreover, the risk for developing CRC for members of families with genetic predisposition to CRC, specifically Lynch Syndrome, is approximately nine times higher than general population risk [5–8].

A family history of CRC also has a major influence on recommendations for CRC screening. For average risk populations without a family history of CRC, screening is recommended to begin at age 50 with any of several screening tests (annual stool tests, sigmoidoscopy every five years with or without a stool test, or colonoscopy every 10 years) [9,10]. Surveillance increases with family history of CRC. It is currently recommended that first-degree relatives of patients with CRC under age 60 be screened with colonoscopy starting at age 40 or 10 years prior to the earliest CRC diagnosis in the family no less than every five years [9,10]. Because of their markedly increased CRC risk, members of families with Lynch Syndrome are advised to have colonoscopy screening every one to two years starting at age 20–25 or two to five years prior to the earliest CRC if it is diagnosed before age 25 [10]. About three to five percent of the population is thought to fall into one of these high risk groups [3,11] but they represent a disproportionate number of incident CRC and CRC deaths, which magnifies the importance of screening adherence in these families.

Despite the established efficacy of endoscopy screening to reduce CRC incidence and mortality [12–15], adherence to CRC screening remains suboptimal even in these high risk groups [16–20]. The Family Health Promotion Project (FHPP) was a randomized, controlled trial to test the effectiveness of a telephone-based, counseling intervention to increase adherence to colonoscopy screening in members of high risk CRC families. The study design and results from the baseline survey have been described previously [17]. We report here the primary outcome data for FHPP; the effect of the intervention on colonoscopy screening adherence.

Materials and Methods

Trial Design Overview

The FHPP was a multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. Participants at increased for CRC as described below were recruited from two national cancer family registries, the Colon Cancer Family Registry (C-CFR) and the Cancer Genetics Network (CGN) between February 2005 and July 2006 [21–22]. Consenting participants completed a baseline survey and were randomized to receive either a tailored, one time telephone-based counseling intervention (tailored telephone intervention) or a mailed packet. Participants were mailed follow-up assessments at 6, 12, and 24 months to assess screening behavior as well as participants’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about CRC screening and barriers to having screening (ex. cost, no symptoms, busy, fear/anxiety about the test, worry about the prep)[17]. Questions on the baseline and follow up surveys were adapted and validated from previous studies [17, 23–25]. The primary outcome for the study was prevalence of colonoscopy screening in the two groups within the 24-month study period from randomization. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (IRB #03-858).

Participants

Participants were recruited from eight C-CFR and three CGN registry sites; CGN centers: Universities of Utah (n=61), New Mexico (n=4) and Colorado (n=51); C-CFR centers: Universities of Arizona (n=25), North Carolina (n=16), Minnesota (n=56), Southern California (n=5) and Colorado (n=38), the Cleveland Clinic (n=95), Mayo Clinic (n=95) and The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (n=185). Eligible participants were unaffected with CRC, at least 21 years of age, English speaking and at increased risk for CRC on the basis of their family history. Two classes of increased risk were defined. Participants from families that met the Amsterdam II criteria for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC): three biological relatives with CRC or other HNPCC-associated cancers with one being a first degree relative of the other two and at least two generations affected, and one cancer diagnosis under 50 years of age [7], were classified as ‘HNPCC’ participants. We used the term HNPCC for these participants because genetic testing had not been confirmed for these families and the term Lynch Syndrome is typically reserved for families with confirmed mutations in a DNA mismatch repair gene. Participants that had at least one first-degree relative diagnosed with CRC under age 60 or two or more first-degree relatives diagnosed with CRC at any age were defined as ‘High Risk’. Eligible participants must have been due for colonoscopy during the 24-month study period according to consensus guidelines for these populations. Because recommended that individuals from HNPCC families have colonoscopy every one to two years, all of these participants would have been due for colonoscopy during the 24 month period and thus eligible. The recommendation for High Risk participants is to have colonoscopy no less than every five years. Thus High Risk participants who had a colonoscopy within the three years prior were excluded, as they would not have been due to have another colonoscopy during the study period.

Recruitment and Randomization

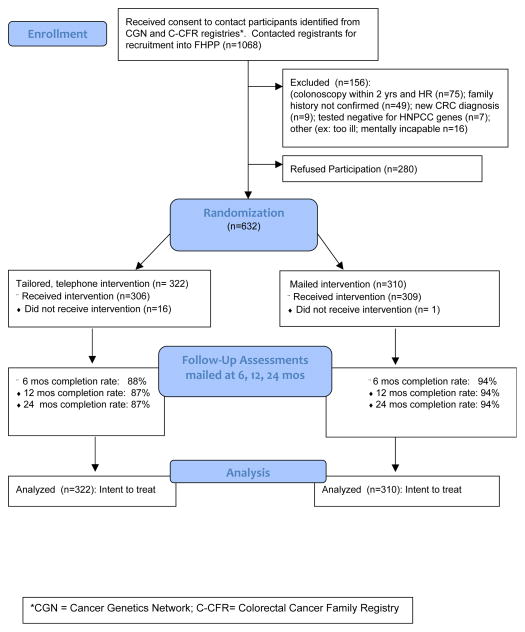

Upon receiving permission to contact participants from their respective registry site, FHPP staff at the University of Colorado Cancer Center contacted participants to recruit them into the study (n=1,068). Of the 1,068 subjects contacted, 156 were deemed ineligible and 280 refused participation for an overall response rate of 69% (632 of 912 eligible) (Figure 1). The 632 consenting participants, representing 533 families, completed the baseline survey and were randomized to receive either the tailored, telephone counseling intervention (N=322) or the general mailed intervention (N=310). Block randomization was employed to assure equal distribution of participants across intervention groups by recruitment site, CRC risk level (HNPCC vs. High Risk) and by family unit to avoid experimental contamination.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram for FHPP Trial

*CGN = Cancer Genetics Network; C-CFR = Colorectal Cancer Family Registry

Tailored, Telephone Counseling and Mailed Intervention

The components of the telephone counseling intervention have been described in detail previously [17]. Briefly, the counseling intervention was delivered by trained interviewers using tailored messages based on participants’ responses to the baseline survey and motivational interviewing (MI) techniques. The intervention was grounded in several theoretical models to promote behavior change including the Health Belief Model [26–28], the Theory of Planned Behavior [29–31] and the Transtheoretical Model [32–34]. The counseling intervention was conducted using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) software of the Survey Core of the University of Colorado Cancer Center. Upon establishing telephone contact, the interviewers began the session by eliciting the participants’ readiness (stage of change) to have colonoscopy. Based on their response (1-ready, 2- ready but with some reservation, or 3- not ready), the interviewer appropriately engaged the participant in conversation about their perceived risk of CRC, risk-appropriate screening guidelines, the pros and cons of CRC screening, and perceived barriers.. Information from the participant’s baseline assessment regarding these factors was incorporated into the interview, which allowed the interviewers to tailor the counseling session to focus on specific barriers and/or information gaps (ex. knowledge of screening intervals specific to their risk level). At the end of the session, the interviewers engaged the participants in developing an individualized action plan that was appropriate based on their readiness to be screened. Action items ranged from talking with their family members about the benefits of screening, to calling their provider to obtain a referral for colonoscopy. The average intervention session lasted between 20 and 30 minutes. Following the telephone counseling session, participants were mailed a summary of the issues discussed including their personalized action plan that was extracted directly from the CATI software. Participants were sent a reminder postcard in the month prior to their colonoscopy due date.

Participants randomized to the mailed intervention group were mailed a letter stating the importance of maintaining a healthy lifestyle through exercise, diet and routine screening for reducing risk of cancer and other chronic diseases, and were sent a Choices for Good Health brochure, sponsored by the American Cancer Society. Participants were also encouraged to speak with their doctors about options for CRC screening, which may be different given their family history of CRC.

Study Outcome: Colonoscopy screening

The primary outcome of the FHPP was the prevalence of colonoscopic screening at the end of the study period as reported on at least one of the follow-up assessments. Each assessment asked the participant whether (and when) they had had colonoscopy since the time of the previous survey. Participants who reported having had colonoscopy were asked to provide consent to obtain endoscopy and pathology reports to verify screening. Endoscopy reports were obtained for 98% of reported colonoscopies. Concordance between self-reported colonoscopies and endoscopy reports was 100%. Thus, we included all reported colonoscopies including the five (2%) for which we could not obtain endoscopy reports in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

To assess the effectiveness of randomization, we compared demographic characteristics between intervention groups using repeated measures models to accounts for familial clustering. These models were also used to assess any differences between groups with respect to baseline characteristics related to CRC screening such as past screening history, knowledge of guidelines, intentions to screen, risk perception and barriers to screening. McNemar’s test was used to assess change in the percent of participants who were adherent from baseline to 24 months within study groups [35]. To account for the variability in the length of follow-up due to participant dropout or inability to contact, we employed survival analysis techniques to test our main hypothesis of greater adherence to colonoscopy in the telephone counseling intervention group compared to the mailed intervention group at 24 months. Responses were censored at the time of colonoscopy or at time of the last completed follow-up assessment. Cox proportional hazards methods [36] were used to assess the effectiveness of the telephone intervention while adjusting for any confounding variables identified. Regression parameters in the Cox models were estimated using a robust sandwich covariance matrix estimate to account for the familial clustering [37]. An intent-to-treat approach was used; thus all participants that were randomized were included in the analysis. Possible interaction effects by risk status were assessed. The sample size was established to enable detection of a relative difference in colonoscopy adherence of 15% overall between intervention groups at 24 months with 80% power.

Results

A total of 632 participants were enrolled in the FHPP trial. Of the 322 participants randomized to the telephone intervention, 306 (95%) received the intervention (16 participants could not be reached by phone within the allotted time frame per protocol), and 309 of 310 (>99%) participants in the mailed group received the mailed packet. Retention of participants over 24-months was greater than 90% overall; 87% in the telephone and 94% in the mailed intervention group.

Characteristics of study participants by intervention group are shown in Table 1. Twenty-five percent of participants (N=125) met criteria for HNPCC and 75% (N=467) were classified as High Risk. Approximately 60% of the participants were women, and the majority were age 50 or older, Caucasian and non-Hispanic. The study population was generally well educated, and over 90% had health insurance and a regular primary physician. A higher percentage of participants in the mailed intervention group had at least some college education (p=0.02) but the other demographic variables were balanced between the two intervention groups (Table 1). There were no significant differences between participants who consented compared to those who declined participation with respect to gender, age, race/e ethnicity or risk level.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics by Intervention Group (N=632)

| Characteristic | Intervention Group

|

p-value for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tailored Telephone (N=322) N (%) |

Mailed (N=310) N (%) |

||

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 137 (43) | 124 (40) | 0.40 |

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| < 40 | 19 (6) | 17 (5) | |

| 40 – 49 | 88 (27) | 64 (21) | |

| 50 – 64 | 132 (41) | 140 (45) | 0.50 |

| 65+ | 83 (26) | 89 (29) | |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| African American | 7 (2) | 4 (1) | |

| Caucasian | 299 (93) | 290 (94) | 0.62 |

| Other | 10 (3) | 13 (4) | |

| Missing | 4 | 3 | |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 9 (3) | 6 (2) | 0.46 |

| Non-Hispanic | 307 (95) | 298 (96) | |

| Missing | 6 | 6 | |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| Post college | 59 (18) | 58 (19) | |

| College graduate | 81 (25) | 94 (30) | |

| Some college/tech | 93 (29) | 102 (33) | 0.02 |

| High school | 72 (22) | 49 (16) | |

| Less than high school | 14 (4) | 6 (2) | |

| Missing | 3 | 1 | |

|

| |||

| Risk level | |||

| HNPCC* | 81 (25) | 84 (27) | 0.91 |

| High Risk | 241 (75) | 226 (73) | |

|

| |||

| Household Income | |||

| $70,000 or more | 122 (38) | 113 (36) | |

| $45,000 – $69,999 | 81 (25) | 78 (25) | |

| $30,000 – $44,999 | 52 (16) | 54 (17) | 0.51 |

| $15,000 – $29,999 | 29 (9) | 39 (13) | |

| < $15,000 | 16 (5) | 12 (4) | |

| Missing | 22 | 14 | |

|

| |||

| Have Health Insurance | |||

| Yes | 310 (96) | 293 (95) | 0.54 |

|

| |||

| Have regular doctor | |||

| Yes | 291 (90) | 291 (94) | 0.11 |

Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer

Due to rounding and missing data, percentages do not always add to 100%

Despite randomization, comparison of baseline attitudes, beliefs and behaviors related to CRC screening revealed several significant differences between the intervention groups (Table 2). Participants in the mailed group were less likely than those in the telephone intervention group to report barriers to screening (63% vs. 71%, p=0.048) and more likely to be adherent with CRC screening (52% vs. 43%; p=0.04). There was also a trend toward a higher level of knowledge of screening recommendations in the mailed group (54% vs. 47%; p=0.06). Over 70% of participants in both groups reported having at least one previous colonoscopy, but only about 50% said they intended to have a colonoscopy within the next 24 months. Over 80% of all participants recognized that they were at elevated risk for CRC.

Table 2.

Baseline colorectal cancer (CRC) screening behaviors, knowledge and perceived CRC risk by intervention group (N=632)

| Baseline survey question | Intervention Group

|

p-value for difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tailored Telephone (N=322) N (%) |

Mailed (N=310) N (%) |

||

|

| |||

| Ever had colonoscopy | 239 (74.2) | 238 (76.8) | 0.34 |

|

| |||

| Adherent with CRC screening at baseline* | 139 (43.2) | 161 (51.9) | 0.04 |

|

| |||

| Intend to have colonoscopy in next 1–2 years | 163 (50.6) | 163 (52.6) | 0.46 |

|

| |||

| Knowledge of risk-appropriate screening recommendations** | 151 (46.9) | 166 (53.5) | 0.06 |

|

| |||

| Risk perception higher than others without family history | 263 (81.7) | 253 (81.6) | 0.90 |

|

| |||

| Barriers to CRC screening: | |||

| Reported one or more barrier | 228 (70.8) | 196 (63.4) | 0.048 |

| Median # of barriers (range) | 2.00 (1–14) | 2.00 (1–13) | |

Adherent for participants from Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) families = colonoscopy within past 2 years and for participants from High Risk families =within past 5 years

for HNPCC reported recommendation of ‘every 1–2 years’; for High Risk reported interval no less frequent than every 5 years

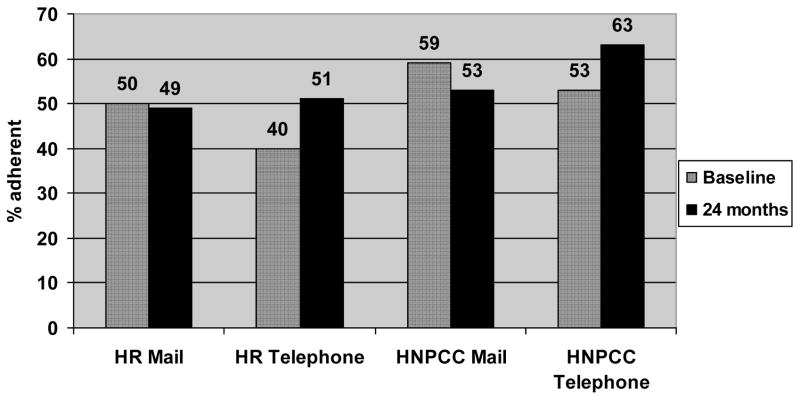

In total, 328 participants reported having had a colonoscopy during follow-up. The proportion of participants who were adherent with colonoscopy at 24 months compared to baseline was assessed. In the mailed intervention group, adherence with colonoscopy at baseline was 52.1% and it was slightly lower (49.8%) at 24 months. In the tailored, telephone intervention group, the prevalence of adherence was 43.2% at baseline and increased by 11 percentage points to 54.0%. Eleven participants in the telephone and 10 in the mailed group had colonoscopy within one month of randomization, suggesting these may have been scheduled prior to randomization. When stratified by risk level, we found that the HNPCC group had greater overall adherence at 24 months compared to the High Risk group but the absolute difference in adherence from baseline to 24 months for the HNPCC and High Risk participants in the telephone intervention group was comparable (about 11 percentage points) [Fig 2]. There was no increase in colonoscopy adherence from baseline for either risk group among participants who received the mailed intervention.

Figure 2.

Colonoscopy adherence by risk level (High Risk (HR) vs. Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colon Cancer (HNPCC)) and intervention group at baseline and 24 months

Results from bivariate and multivariate analyses are shown in Table 3. In unadjusted bivariate analysis, using an intent-to-treat approach, the tailored, telephone intervention was associated with a 24% increase in colonoscopy adherence at 24 months (Hazard Ratio = 1.24, p=0.04). Baseline factors that were significantly associated with greater adherence included having had a previous colonoscopy, intent to have screening, appropriate CRC risk perception, and knowledge of risk-appropriate screening intervals. Not having a regular doctor was associated with lower adherence as was having one or more perceived barriers to screening. Age, gender, education, insurance status, adherence at baseline, and risk level did not significantly predict adherence. After adjusting for significant covariates in multivariate analysis, we found that the tailored, telephone intervention was associated with a 32% increase in colonoscopy adherence (Hazard Ratio=1.32, p=0.01). Previous colonoscopy and intent to have colonoscopy in the next 1–2 years were also associated with increased adherence in the multivariate model.

Table 3.

Results from bivariate and multivariate analysis to assess the degree of screening compliance by baseline factors and intervention group (N=632)

| Subject Characteristic | Bivariate Analysis Hazard Ratio (95% C.I.) (p-value) | Multivariate Analysis† Hazard Ratio (95% C.I.) (p-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (yrs) | |||

| 25–39 | 1.00 | - | |

| 40–49 | 0.96 (0.52, 1.76) | ||

| 50–64 | 1.14 (0.64, 2.05) | ||

| 65+ | 1.28 (0.70, 2.33) | ||

|

| |||

| Male gender | 0.86 (0.69, 1.08) | - | |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| No college (vs. some college or more) | 1.14 (0.88, 1.48) | - | |

|

| |||

| No doctor | 0.54 (0.30, 0.96) (0.02) |

- | |

|

| |||

| No insurance | 0.55 (0.27, 1.14) | - | |

|

| |||

| Risk group – HNPCC (vs. HR) | 1.15 (0.91, 1.45) | - | |

|

| |||

| Ever had colonoscopy | 1.74 (1.27, 2.38) (0.0003) |

1.47 (1.06, 2.04) (0.02) |

|

|

| |||

| Adherent at baseline | 1.08 (0.87, 1.34) | - | |

|

| |||

| Plan on having colonoscopy in 1–2 years | 2.98 (2.37, 3.75) (<0.0001) |

2.90 (2.30, 3.65) (<0.0001) |

|

|

| |||

| Risk perception is higher than others without family history | 1.73 (1.27, 2.35) (0.0003) |

- | |

|

| |||

| Knowledge of risk appropriate recommendations | 1.33 (1.07, 1.65) (0.01) |

- | |

|

| |||

| Reported barriers to CRC screening Any barrier (yes vs. no) | 0.73 (0.58, 0.92) (0.007) |

- | |

|

| |||

| Intervention Arm – Intensive | 1.24 (1.01, 1.55) (0.04) |

1.32 (1.07, 1.64) (0.01) |

|

Adjusted for all variables with significance level of p < 0.05 in multivariate model

Discussion

Results from the FHPP trial demonstrate that a tailored, educational and barriers counseling intervention delivered by telephone can effectively increase adherence to colonoscopy screening among members of high-risk CRC families. To our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial to successfully promote colonoscopy screening in high-risk populations that included individuals from HNPCC families. Efforts to increase both initial screening and maintenance of screening adherence in these groups is important both because they have a substantially increased CRC risk and they continue to demonstrate relatively low screening adherence.

In this trial, we found that although over 80% of our participants were aware that they were at increased CRC risk, less than 50% were adherent with recommended screening intervals at enrollment [Table 2], which is consistent with reports from previous studies [16–20,38]. One explanation for the low adherence at baseline in our participants appears to be a lack of knowledge of risk appropriate screening intervals. As previously reported, only 22% of HNPCC and 52% of High Risk participants knew the recommended colonoscopy screening interval based on their family history [17]. Given that a significant number of individuals in the general population are predisposed to CRC due to a strong family history (about 3–5%) [3,11] and the persistent low rates of screening in these groups, interventions that even moderately increase screening have the potential to effectively reduce CRC morbidity and mortality in these families, and in the population at-large.

By chance, the proportion of participants who were adherent with colonoscopy guidelines at baseline (but as required for eligibility, due for their next screening within 24 months) was significantly lower among participants randomized to the telephone intervention than in those in the mailed intervention (43% vs. 52%; p=0.04). Nonetheless, our results showed an 11% absolute increase in colonoscopy screening prevalence from baseline to 24 months (43% to 54%, p<0.004) among participants who received the telephone counseling intervention compared to essentially no change in adherence among participants randomized to the mailed group (52% vs. 50%, p=0.56). The multivariate analysis that accounted for the difference in baseline adherence showed that participants who received the telephone intervention were 32% more likely to have colonoscopy during follow-up than those in the mailed group.

The counseling intervention appeared to be effective in both the HNPCC and High Risk groups. Adherence to colonoscopy upon completion of the study was somewhat higher in the HNPCC group, which is important given their significant CRC risk, and consistent with previous reports of higher screening prevalence in this population following genetic education and counseling [39–42]. However, the absolute difference in adherence was similar in both risk groups. This is encouraging, as an intervention that increases adherence in both risk groups would have wider applicability. It can be difficult to clinically distinguish the two risk groups without having a complete family history, which is rarely collected in clinical practice [43–46].

There have been few randomized studies of interventions to specifically promote colonoscopy adherence among individuals at increased risk for CRC due to family history, and none to our knowledge, that have included persons from HNPCC families [47]. A study by Manne et al [48] evaluated the effect of three increasingly intense behavioral interventions on CRC screening adherence in siblings of CRC survivors: generic print materials vs. tailored print materials vs. tailored print plus telephone counseling. Results from this study showed that while all three interventions increased adherence, adherence was significantly higher in each of the tailored groups compared to the generic group (25% and 26% vs. 14%, respectively) though there was no difference in adherence between the tailored print and tailored print plus telephone counseling groups. A second, smaller study by Rawl et al [49] that compared the effect of two print interventions (generic vs. tailored) to increase CRC screening among siblings and children of CRC cases similarly demonstrated that both interventions increased adherence (21% and 14% at 12 months), but found no difference in adherence between the tailored and generic print groups. Finally, a trial by Glanz et al [50] tested the effect of using face-to-face risk counseling (vs. general health counseling) to increase screening adherence among siblings of CRC cases. This intensive intervention resulted in a net change in adherence (above the general counseling group) of 13 and 11 percentage points at 4 and 12 months respectively.

Variability across studies with respect to study population, screening outcome, intervention intensity and mode of delivery, make it challenging to directly compare results. For FHPP, we included participants who were adherent at baseline but who were at risk for becoming non-adherent during the study period, whereas other studies specifically excluded these individuals [48–49]. We also limited our outcome to colonoscopy screening, where others have included additional CRC screening modalities [49–50]. In addition, our trial did not include a ‘tailored-print’ arm with which to specifically compare our telephone intervention. Nonetheless, our finding of a net change in adherence of 11 percentage points in our telephone intervention group over that of our control group, is similar to that reported in two previous trials [48, 50]

Taken together, with some exceptions, results from our study and others’ suggest that tailored interventions may be more effective in promoting screening in high risk groups [47–48, 50]. Using tailored messages is particularly relevant when addressing populations of various risk profiles as we had in FHPP, and when attempting to promote both initial screening as well as adherence to recommended screening intervals, which differ depending on risk. It remains unclear as to whether print vs. telephone delivery would be equally effective. The challenge to using a tailored approach in practice is having adequate information about the target population a priori such as family history and known barriers, which is often not available. One benefit of using a phone-based approach is the ability to assess risk, readiness and barriers in real time that can be directly translated into tailored messages.

The FHPP study has many strengths including a prospective, randomized, controlled design, high response and retention rates and validation of self-reported colonoscopies with endoscopy reports. The use of two NCI-funded registries allowed the identification of (HNPCC and High Risk) participants with well characterized and updated family history information available. Having information about risk a priori allowed us to tailor the intervention to appropriately address issues of CRC risk and recommended screening intervals. Use of the CATI technology allowed the counseling intervention to be tailored in real time and importantly, to address any persisting barriers to screening. For example, for participants who shared that cost was an issue or that they did not feel that screening was necessary since they did not have symptoms (two of the most common barriers), the interviewers were able to counsel them on how to approach their provider to discuss payment options, and were able to immediately reinforce to participants that screening is most effective for preventing cancer before symptoms arise. These messages were included in the action-plan that was discussed and reiterated in the follow-up letter. Finally, the use of motivational interviewing techniques allowed the interviewers to assess and tailor messages that were appropriate for participants’ readiness to undergo screening [17].

Our study also has some limitations. Our participants were also mostly White, affluent, had health insurance, and higher education levels, and were all English-speaking, which may limit generalization of our findings. Similarly, by virtue of their participation in the registries, our participants may be different than other high-risk individuals in that they may be more aware of their risk and the importance of screening, and therefore more motivated to undergo screening. It is possible that participants who had colonoscopy within a month of randomization had scheduled this prior to receiving the intervention. However, this number was small and comparable across groups, thus it is unlikely that this significantly affected our results. Despite the overall large sample size, the smaller size of the HNPCC subset (n=165) limited the power to assess interactions. Finally, randomization did not result in equal distribution of several important variables including baseline adherence to colonoscopy. This may in part have been due to clustering of family members within intervention groups, who may have similar screening practices. This difference attenuated the effect of the intervention in that at 24 months the absolute screening prevalence in the two intervention groups was similar.

In conclusion, the FHPP trial demonstrated that a relatively brief but tailored telephone-based, education and barriers counseling intervention can increase colonoscopy screening in persons at increased risk for CRC due to their family history. As designed, our intervention, which was tailored in real-time by non-medical interviewers, has the potential for broad dissemination into health-care organizations or populations (such as high risk registries) that have the capacity to identify persons at increased risk. Though our intervention effectively increased adherence, there remained a subset of participants who were non-adherent, highlighting the need for continued efforts to identify strategies for improving adherence in these high risk groups. These efforts may start with enhancing systems for identifying persons with familial risk, ensuring that providers are aware of risk appropriate guidelines and enlisting patient navigators to assist patients who face significant barriers to screening. Eliciting patients’ barriers, mutually identifying ways to overcome these and developing an action plan for taking next steps, may help to increase screening in these more resistant populations. Analyses are underway to identify specific components from our intervention that were most likely to increase colonoscopy adherence, which will inform the nature and viability of broader dissemination of this intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Grant #5R01CA68099 (D Ahnen), and supported by the University of Colorado Cancer Center Core Grant #P30CA046934 (D Theodorescu). The Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (C-CFR) was supported by the NCI, National Institutes of Health under RFA # CA-95-011 and through cooperative agreements with members of the C-CFR and P.I.s: Familial Colorectal Neoplasia Collaborative Group (U01 CA074799; R Haile); Mayo Clinic Cooperative Family Registry for Colon Cancer Studies (U01 CA074800; L Lindor); Seattle Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (U01 CA074794; P Newcomb). The Cancer Genetics Network was supported through cooperative agreements (U01CA078284; D Finkelstein), (U24CA078164; D Bowen), (U24CA078174; G Mineau) and a contract (HHSN2612007440000C; D Finkelstein) from the NCI.

We would like to acknowledge the participating C-CFR and CGN Centers who contributed participants for this trial: Theresa Mickiewicz and Meg Rebull (Colorado), Sandra Nigon (Mayo Clinic), Allyson Templeton (Seattle), Pat Harmon (USC Consortium), Terry Teitch (Dartmouth), Deb Ma (Utah), Lori Ballinger (New Mexico); and Al Marcus (Co-PI, University of Colorado Cancer Center) for his expertise, leadership and valuable contributions to this work.

We also acknowledge Carol Kasten, MD, Epidemiology and Genetics Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Prevention Sciences, National Cancer Institute, for her contributions to the conception and design of the CGN.

Footnotes

The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the NCI or any of the collaborating centers in the CFRs, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government or the C-CFR.

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: Apr, 2013. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Speizer FE, Willet WC. A prospective study of family history and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Eng J Med. 1994;331:1669–1674. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412223312501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burt RW, DiSario JA, Cannon-Albright L. Genetics of colon cancer: impact of inheritance on colon cancer risk. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:371–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johns LE, Houlston RS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Oct;96(10):2992–3003. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowty JG, Win AK, Buchanan DD, Lindor NM, Macrae FA, Clendenning M, et al. Cancer risks for MLH1 and MSH2 mutation carriers. Hum Mutat. 2013 Mar;34(3):490. doi: 10.1002/humu.22262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonadona V, Bonaïti B, Olschwang S, Grandjouan S, Huiart L, Longy M, et al. Cancer risks associated with germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 genes in Lynch syndrome. JAMA. 2011 Jun 8;305(22):2304–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasen HF, Wijnen JT, Menko FH, Kleibeuker JH, Taal BG, Griffioen G, et al. Cancer risk in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer diagnosed by mutation analysis. Gastroenterology. 1996 Apr;110(4):1020–7. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8612988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aarnio M, Sankila R, Pukkala E, Salovaara R, Aaltonen LA, de la Chapelle A, et al. Cancer risk in mutation carriers of DNA-mismatch repair genes. Int J Cancer. 1999 Apr 12;81(2):214–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990412)81:2<214::aid-ijc8>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Cancer Society. [Accessed July 2013];Recommendations for Colorectal Cancer Screening. < http://www.cancer.org/cancer/colonandrectumcancer/moreinformation/colonandrectumcancerearlydetection/colorectal-cancer-early-detection-acs-recommendations>.

- 10.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [Accessed July 2013];Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. < http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colorectal_screening.pdf>.

- 11.Mitchell RJ, Farrington SM, Dunlop MG, Campbell H. Mismatch Repair Genes hMLH1 and hMSH2 and Colorectal Cancer: A HuGE RevieHuman Genome Epidemiology (HuGE) Review. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156 (10):885–902. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Järvinen HJ, Aarnio M, Mustonen H, Aktan-Collan K, Aaltonen LA, Peltomäki P, et al. Controlled 15-year trial on screening for colorectal cancer in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2000 May;118(5):829–34. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Aarnio M, Mecklin JP, Järvinen HJ. Surveillance improves survival of colorectal cancer in patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2000;24(2):137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niv Y, Dickman R, Figer A, Abuksis G, Fraser G. Case-control study of screening colonoscopy in relatives of patients with colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Feb;98(2):486–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dove-Edwin I, Sasieni P, Adams J, Thomas HJ. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic surveillance in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer: 16 year, prospective, follow-up study. BMJ. 2005 Nov 5;331(7524):1047. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38606.794560.EB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin OS, Gluck M, Nguyen M, Koch J, Kozarek RA. Screening patterns in patients with a family history of colorectal cancer often do not adhere to national guidelines. Dig Dis Sci. 2013 Jul;58(7):1841–8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2567-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowery JT, Marcus A, Kinney A, Bowen D, Finkelstein DM, Horick N, et al. The Family Health Promotion Project (FHPP): design and baseline data from a randomized trial to increase colonoscopy screening in high risk families. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012 Mar;33(2):426–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor DP, Cannon-Albright LA, Sweeney C, Williams MS, Haug PJ, Mitchell JA, et al. Comparison of compliance for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance by colonoscopy based on risk. Genet Med. 2011 Aug;13(8):737–43. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182180c71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruthotto F, Papendorf F, Wegener G, Unger G, Dlugosch B, Korangy F, et al. Participation in screening colonoscopy in first-degree relatives from patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007 Sep;18(9):1518–22. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rees G, Martin PR, Macrae FA. Screening participation in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer: a review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;17:221–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anton-Culver H, Ziogas A, Bowen D, Finkelstein D, Griffin C, Hanson J, et al. Cancer Genetics Network: Recruitment results and pilot studies. Community Genetics. 2003;6(3):171–177. doi: 10.1159/000078165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newcomb PA, Baron J, Cotterchio M, Gallinger S, Grove J, Haile R, et al. Colon Cancer Family Registry: an international resource for studies of the genetic epidemiology of colon cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007 Nov;16(11):2331–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcus AC, Ahnen D, Cutter G, Calonge N, Russell S, Sedlacek SM, et al. Promoting cancer screening among the first degree relatives of breast and CRC patients: The design of two randomized trials. Prev Med. 1999;28(3):229–42. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baier M, Calonge N, Cutter G, McClatchey M, Russell S, Hines S, et al. Use of a Telephone survey to estimate validity of self-reported colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:229–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rakowski W, Ehrich B, Dube CE, Pearlman DN, Goldstein MG, Peterson KK, et al. Screening mammography and constructs from the transtheoretical model: associations using two definitions of the stages-of-adoption. Ann Behav Med. 1996;18:91–100. doi: 10.1007/BF02909581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janz NK, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly. 1984;11(1):1–47. doi: 10.1177/109019818401100101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The Health Belief Model. In: Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 3. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2002. pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ajzen I. Theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ajzen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22:453–474. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montano DE, Kasprzyk D. The Theory of Reasoned Action and The Theory of Planned Behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 3. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2002. pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prochaska JO. Strong and weak principles for progressing from precontemplation to action based on twelve problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994;13:47–51. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Evers KE. The Transtheoretical Model and stages of change. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 3. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass; 2002. pp. 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. 2. Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2003. Cox Proportional Hazards Model D. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee EW, Wei LJ, Amato D. Cox-Type Regression Analysis for Large Numbers of Small Groups of Correlated Failure Time Observations. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic; 1992. pp. 237–47. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Courtney RJ, Paul CL, Carey ML, Sanson-Fisher RW, Macrae FA, D’Este C, et al. A population-based cross-sectional study of colorectal cancer screening practices of first-degree relatives of colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2013 Jan 10;13:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stoffel EM, Mercado RC, Kohlmann W, Ford B, Grover S, Conrad P, et al. Prevalence and predictors of appropriate colorectal cancer surveillance in Lynch syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Aug;105(8):1851–60. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bleiker EM, Menko FH, Taal BG, Kluijt I, Wever LD, Gerritsma MA, et al. Screening behavior of individuals at high risk for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(2):280–287. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hadley DW, Jenkins JF, Dimond E, de Carvalho M, Kirsch I, Palmer CG. Colon cancer screening practices after genetic counseling and testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:39–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halbert CH, Lynch H, Lynch J, Main D, Kucharski S, Rustgi AK, et al. Colon cancer screening practices following genetic testing for hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) mutations. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1881–1887. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.17.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sifri RD, Wender R, Paynter N. Cancer risk assessment from family history: gaps in primary care practice. J Fam Practice. 2002 Oct;51(10):856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sweet KM, Bradley TL, Westman JA. Identification and referral of families at high risk for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(2):528–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.2.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tyler CV, Snyder CW. Cancer risk assessment: examining the family physician’s role. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(5):468–77. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.5.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murff HJ, Greevy RA, Syngal S. The comprehensiveness of family cancer history assessments in primary care. Community Genet. 2007;10(3):174–80. doi: 10.1159/000101759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rawl SM, Menon U, Burness A, Breslau ES. Interventions to promote colorectal cancer screening: an integrative review. Nurs Outlook. 2012 Jul-Aug;60(4):172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manne SL, Coups EJ, Markowitz A, Meropol NJ, Haller D, Jacobsen PB, et al. A randomized trial of generic versus tailored interventions to increase colorectal cancer screening among intermediate risk siblings. Ann Behav Med. 2009 Apr;37(2):207–17. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9103-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rawl SM, Champion VL, Scott LL, Zhou H, Monahan P, Ding Y, et al. A randomized trial of two print interventions to increase colon cancer screening among first-degree relatives. Patient Educ Couns. 2008 May;71(2):215–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glanz K, Steffen AD, Taglialatela LA. Effects of colon cancer risk counseling for first-degree relatives. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007 Jul;16(7):1485–91. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.