Abstract

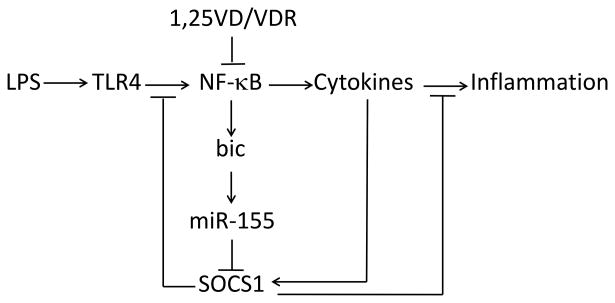

Macrophages play a critical role in innate immune response to protect the host from pathogenic microorganisms. Inflammatory response is regulated by negative feedback mechanisms to prevent detrimental effects. The SOCS family of proteins is key component of the negative feedback loop that regulates the intensity, duration and quality of cytokine signaling, whereas miR-155 is a key regulator of Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling that targets SOCS1 in activated macrophages to block the negative feedback loop. Recently we showed that 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D3) modulates innate immune response by targeting the miR-155-SOCS1 axis. We found that Vdr deletion leads to hyper inflammatory response in mice and macrophage cultures when challenged with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), due to miR-155 overproduction to excessively suppress SOCS1. Using mice with bic/miR-155 deletion we confirmed that 1,25(OH)2D3 suppresses inflammation and stimulates SOCS1 by down-regulating miR-155. Mechanistically 1,25(OH)2D3 down-regulates bic transcription by blocking NF-κB activation, which is mediated by a κB cis-DNA element identified within the first intron of the bic gene. At the molecular level, we demonstrated that VDR inhibits NF-κB activation by directly interacting with IKKβ protein. Our studies identified a novel mechanism whereby VDR signaling attenuates TLR-mediated inflammation by enhancing the negative feedback regulation.

Keywords: vitamin D, inflammation, macrophage, miR-155, SOCS1, NF-kappaB, IKKbeta, negative feedback loop

Introduction

It is well established that the vitamin D hormone, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D3], through binding to the vitamin D receptor (VDR) [1], plays pleiotropic roles in a wide spectrum of biological functions [2], including modulation of innate and adaptive immunity [3; 4]. The best-known activity of vitamin D in the regulation of innate immunity is to stimulate anti-microbial peptide production in macrophages [5]. Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation by bacterial infection increases the expression of CYP27B1 and VDR in macrophages, resulting in increases in intracellular synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D3 and activation of local 1,25(OH)2D3-VDR signaling, which induces anti-microbial peptide cathelicidin to kill bacteria [6; 7; 5]. This mechanism, however, cannot explain the anti-inflammatory action of vitamin D, in which 1,25(OH)2D3 down-regulates pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in macrophages and other cells [8; 9]. In fact, little is known about the molecular basis of this anti-inflammatory mechanism. In this article we review a novel microRNA-mediated mechanism whereby the vitamin D hormone down-regulates the innate immune response [10].

MicroRNA-155 and immunity

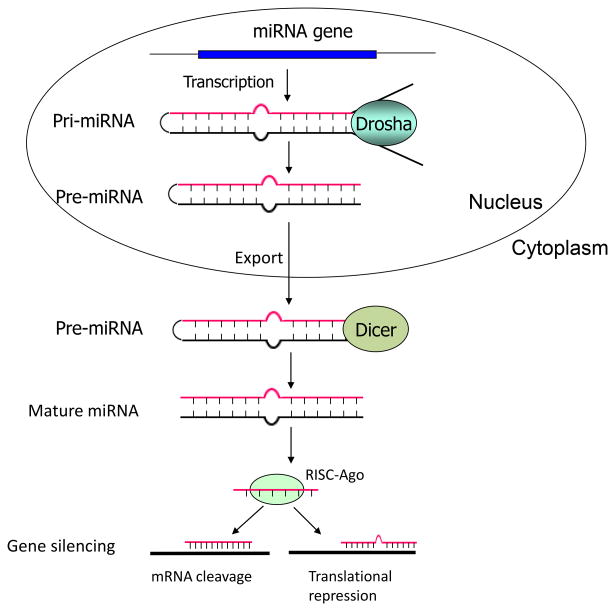

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of naturally occurring small non-coding RNAs of ~22 nucleotides that control gene expression by translational repression or mRNA degradation [11; 12]. Like protein-coding genes, miRNAs are transcribed as long primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs) in the nucleus. The pri-miRNAs are subsequently cleaved to produce stem loop structured precursor of 70-100 nucleotides in length, namely pre-miRNAs, by the nuclear RNase III enzyme Drosha-DGCR8 complex. The pre-microRNAs are then exported to the cytoplasm by exportin-5-Ran-GTP complex, where the RNase III enzyme Dicer-TRBP complex further processes them into mature miRNAs (~22 nucleotides) [13]. In the cytoplasm, one strand of the miRNA duplex is subsequently incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) that mediates target gene repression (Figure 1). It is now well accepted that miRNAs and transcription factors together control a complex network that regulates gene expression in cells.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of miRNA biogenesis. RISC: RNA-induced silencing complex

Many miRNAs have been shown to regulate immune functions, including miRNA-155 that is encoded by a non-coding gene known as bic [14; 15]. miRNA-155 expression has been detected in a variety of cell types in the immune system, including B cells [16], T cells [17], macrophages [18], dendritic cells [19] and hematopoietic progenitor cells [20]. The baseline expression of miRNA-155 in these cells is usually low until stimulation or activation by immune stimuli, such as antigens, Toll-like receptor ligands and inflammatory cytokines, which rapidly increase miRNA-155 expression [18; 21; 16]. It has been shown that bic/miRNA-155 is overexpressed in B cell lymphoma [14; 22; 23]. In fact, transgenic mice over-expressing miRNA-155 in the B cell lineage leads to B cell malignancy [24]. Global knockout of the bic gene leads to immunodeficiency characterized by impaired functions in B and T lymphocytes and dendritic cells [21; 16]. Sustained overexpression of miRNA-155 in the hematopoietic compartment by retrovirus causes a myeloproliferative disorder characterized by increased granulocyte and monocyte populations in the bone marrow and peripheral blood and tissues [20]. Thus miR-155 plays important immuno-modulatory roles.

Roles of macrophages in innate immunity

Macrophages play a central role in innate immune response [25]. Macrophages express CYP27B1 and are able to locally produce 1,25(OH)2D3 on activation by INFγ [26; 27] or by bacterial infection via Toll-like receptors [5]. It has been shown that locally produced 1,25(OH)2D3 triggers the release of bacteria-killing antimicrobial peptide [5]. On the other hand, upon stimulation by stimuli such as microbes, LPS and interferon, activated macrophages release a panel of pro-inflammatory mediators, including cytokines and chemokines, to initiate inflammatory response. Inflammatory reaction is required for the protection of the host from pathogenic microorganisms; however, uncontrolled, over-sustained inflammation is detrimental and can cause tissue damage and even fatality of the host. Thus, negative feedback mechanisms are in place to control the duration and intensity of inflammatory reaction [28].

Negative feedback regulation of inflammatory response

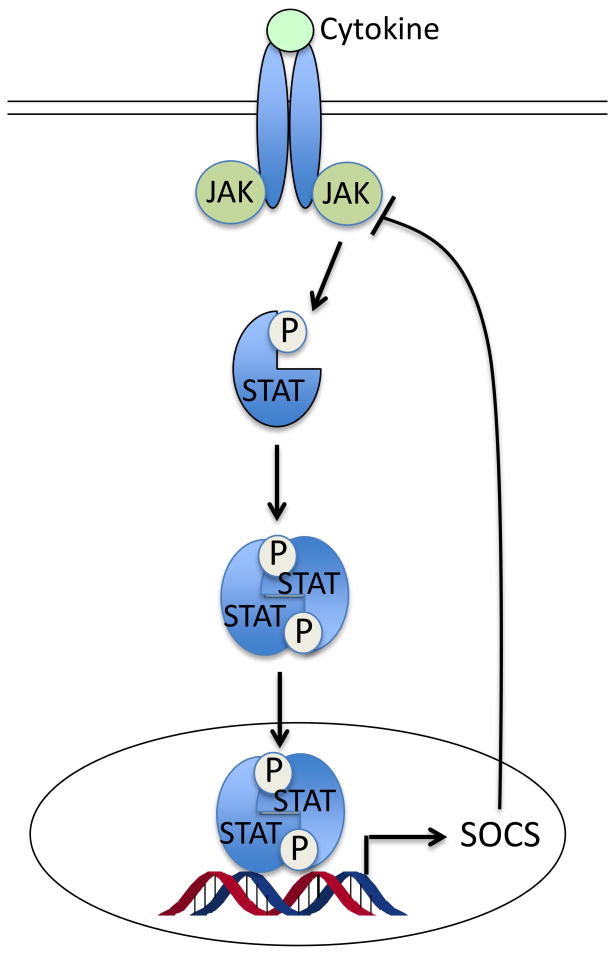

The suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family of proteins are key components of the negative feedback loop that regulates the intensity, duration and quality of cytokine signaling [29]. As feedback inhibitors of inflammation, the SOCS protein is up-regulated by inflammatory cytokines, and in turn blocks cytokine signaling by targeting the JAK/STAT pathway [30] (Figure 2A). SOCS1 is a well-established key negative regulator of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation [31; 32] and inhibits the pro-inflammatory pathways of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6 and INF-γ [33]. SOCS1 also inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory response by directly blocking TLR-4 signaling [31; 32] via targeting IL-1 receptor associated kinase (IRAK)-1 and IRAK4 [34] (Figure 2B). Interestingly, recent studies showed that SOCS1 is a target of miR-155 [35], a microRNA that is highly inducible in macrophages in response to TLR ligands such as LPS [18]. It is thought that by suppressing SOCS1 miR-155 promotes TLR signaling and inflammatory response [36] through blockade of the negative feedback loop.

Figure 2.

Roles of SOCS in feedback regulation of innate immunity. (A) Cytokines bind to membrane receptors and transduce signals through activation of JAK/STAT. SOCS protein is up-regulated by this pathway, and in turn feedback blocks cytokine signaling by targeting the JAK/STAT pathway. (B) SOCS1 inhibits LPS-activated Toll-like receptor signaling pathway by directly blocking IRAK1 and IRAK4.

VDR deletion leads to hyperresponsiveness to LPS

In order to understand the role of VDR in innate immunity, we compared the response of wild-type (WT) and Vdr-/- mice to LPS challenge. We found that after LPS injection all Vdr-/- mice died by 96 hours, whereas 60% of WT mice still survived after 120 hours. Consistently the induction of serum TNFα and IL-6 was much more robust in Vdr-/- mice compared to Vdr+/+ mice. As macrophages play a critical role in innate immunity we directly examined the impact of VDR inactivation on the response of macrophages to LPS. In a time course studies we observed that LPS induced much more robust and prolonged production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β) in bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) from Vdr-/- mice compared to the WT counterpart. These observations indicate that the innate immune response is dysregulated and over-sustained in macrophages when the VDR signaling is inactivated [10].

To validate the importance of VDR in inflammatory regulation we examined the effects of VDR activation in mice and macrophages. We challenged WT mice with LPS after pretreatment with vehicle or a non-calcemic vitamin D analog paricalcitol for one week. Paricalcitol pretreatment substantially suppressed LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-6 production in the serum. Similarly, in BMDM cultures the time-dependent induction of TNF-α and IL-6 production was markedly attenuated by 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment [10].

VDR signaling suppresses miR-155 in macrophages

A growing number of miRNAs have emerged as regulators of immune response [37]. To test whether vitamin D down-regulates inflammation via targeting miRNAs, we examined miRNA profiling by microarrays in RAW264.7 cells, a macrophage cell line, treated with LPS in the presence or absence of 1,25(OH)2D3. Among the miRNAs that were induced the most by LPS and suppressed the most by 1,25(OH)2D3, miR-155 was on the top of the list, with 1,25(OH)2D3 suppressing about 50% of the LPS induction. We validated by Northern blot and qPCR analyses that 1,25(OH)2D3 substantially suppressed LPS-induced miR-155 and bic transcript in RAW264.7 cells as well as in BMDMs. We also confirmed that in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) 1,25(OH)2D3 markedly blocked not only the induction of TNF-α and IL-6 mRNAs by LPS, but also that of bic transcript and miR-155. Interestingly, in Vdr-/- macrophages the levels of bic transcript and miR-155 were elevated at baseline; after LPS stimulation the induction of bic transcript and miR-155 was much more robust and prolonged in Vdr-/-BMDMs compared to Vdr+/+ controls [10]. Together these observations demonstrate that VDR signaling suppresses miR-155 in macrophages.

VDR signaling up-regulates SOCS1 via suppressing miR-155

As a key component of the negative feedback loop SOCS1 is indirectly induced by LPS to maintain the homeostasis of innate immunity [38]. Because SOCS1 is a proved target of miR-155, we expected that vitamin D inhibition of miR-155 would release the suppression on SOCS1, whereas VDR inactivation would depress SOCS1 because of miR-155 elevation. Indeed in RAW264.7 cells the induction of SOCS1 protein by LPS was further enhanced by 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment, whereas LPS was unable to induce SOCS1 protein in Vdr-/- BMDMs due to miR-155 over-expression. To assess the in vivo phenotype of macrophages in response to LPS challenge, we examined peritoneal macrophages immediately harvested from LPS-treated mice. We found that SOCS1 was highly induced in the macrophages from Vdr+/+ mice as expected, but SOCS1 was hardly induced in macrophages obtained from Vdr-/-mice[10]. These results confirm that VDR signaling targets the miR-155-SOCS1 pathway in macrophages. Given the critical role of SOCS1 in the negative feedback loop, these data suggest that VDR signaling constrains inflammatory response by promoting the negative feedback regulation.

miR-155 is required for vitamin D inhibition of inflammation

To explore the role of miR-155 in vitamin D regulation of inflammation, we asked whether miR-155 up-regulation is responsible for the hyper-responsiveness of Vdr-/- macrophages to LPS stimulation. To address this question, we inhibited miR-155 using a miR-155-specific miRIDIAN hairpin inhibitor in Vdr+/+ and Vdr-/- macrophages treated with LPS. We found that, when LPS-induced miR-155 up-regulation was blocked by this hairpin inhibitor, the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6) was markedly attenuated at the protein and transcript levels, whereas the induction of bic transcript was not affected as expected. These results confirm that miR-155 overproduction is a major cause for the hyper inflammation seen in Vdr-/- macrophages.

Next we used the miR-155-null mouse model [16] to further assess the role of miR-155 in vitamin D regulation of innate immunity. We pre-treated WT and bic/miR-155-/- mice with vehicle or paricalcitol for one week before LPS challenge. While paricalcitol substantially blocked the induction of serum pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-a and IL-6) in LPS-treated WT mice as expected, it failed to block the induction of these pro-inflammatory cytokines in bic/miR-155-/- mice. Moreover, using BMDM cultures we observed that, while 1,25(OH)2D3 markedly suppressed LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-6 transcripts in WT BMDMs, this hormone had little effects on the expression of these cytokines in bic/miR-155-/- BMDMs. As expected, SOCS1 induction by LPS was much more robust in bic/miR-155-/- macrophages compared to WT controls. Whereas 1,25(OH)2D3 markedly elevated SOCS1 in WT BMDMs, it failed to induce SOCS1 in bic/miR-155-/- macrophages. Thus miR-155 is required to mediate the anti-inflammatory activity of vitamin D. Together these data provide compelling evidence that vitamin D-VDR signaling maintains SOCS1 levels primarily via suppressing miR-155; consequently, the negative feedback inhibition loop is sustained. Based on these observations we conclude that the vitamin D hormone limits inflammatory response by targeting the miR-155-SOCS1 pathway [10].

1,25(OH)2D3 down-regulates bic transcription via targeting NF-κB

Now the key question is how vitamin D down-regulates bic/miR-155 expression? It has been speculated that NF-κB is involved in the up-regulation of miR-155 [39], but no functional κBcis-DNA elements have been identified in the mouse bic gene promoter. Based on the experiments using NF-κB inhibitor and p65-specific siRNA knockdown we confirmed the importance of NF-κB activation in the induction of bic/miR-155. Through careful in silico analysis we identified a putative κBcis-element within the first intron of the bic gene that shared >95% homology to the canonical κB site. By ChIP assays and EMSA we demonstrated that this κB site is bound by NF-κB; LPS induced NF-κB binding to this site, and the binding was attenuated by 1,25(OH)2D3. Moreover, we generated a luciferase reporter construct using a DNA fragment covering -587 to +263 from the bic gene that contains the intronic κB site or mutant κB site. Luciferase reporter assays showed that LPS markedly stimulated luciferase activity in RAW264.7 cells transfected with the WT luciferase reporter, and the stimulation was attenuated by 1,25(OH)2D3; however, mutations at the κB site eliminated LPS induction and 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibition [10]. These results confirm the functionality of this intronic κBcis-element and reveal that this κB element mediates the down-regulation of bic gene transcription by 1,25(OH)2D3.

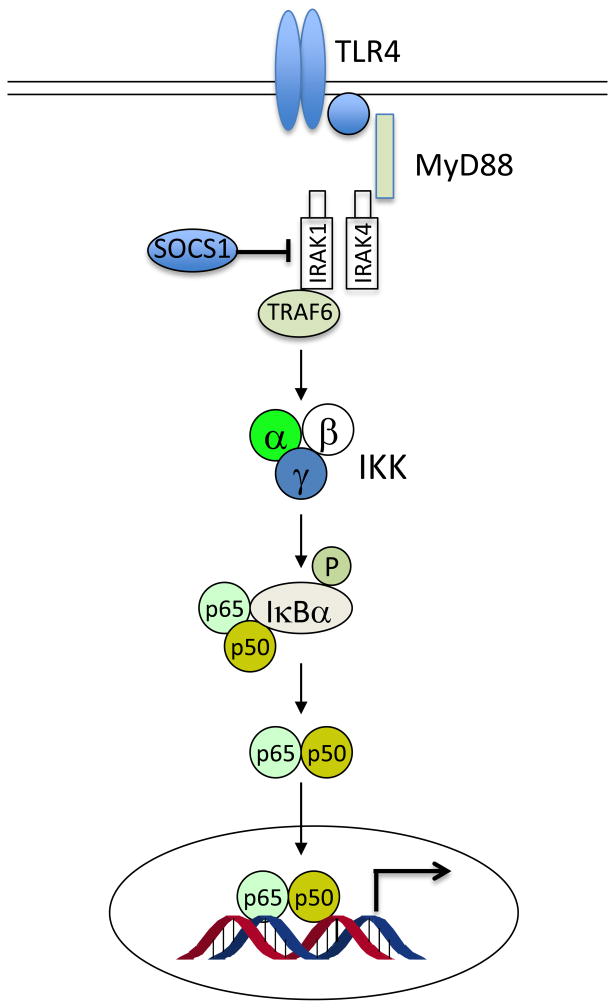

VDR blocks NF-κB activation by interacting with IKKβ

The next important question is how vitamin D inhibits NF-κB? The classic NF-κB activation pathway is a multi-step process that involves a number of key proteins (Figure 3). A crucial negative regulator that controls NF-κB activation is the inhibitor of κB (IκB), which binds to p65 in the cytosol to block the nuclear translocation of the p65/p50 complex. Phosphorylation of IκB by activated IκB kinase (IKK) initiates the ubiquitylation and eventual proteasomal degradation of IκB, which frees p65/p50, allowing entry of p65/p50 to nuclei to transactivate gene expression [40; 41]. Thus IKK plays an essential role in NF-κB activation. The kinase activity of IKK depends on the formation of IKK complex by IKKα, β and γ subunits, which is activated upon phosphorylation by membrane receptor-mediated signals such as activated TLR superfamily [40]. By IKK kinase assays we found that 1,25(OH)2D3 attenuated LPS-induced IκBα phosphorylation in macrophages, which explains why 1,25(OH)2D3 stabilizes IκBα protein reported previously [42; 43]. Immunostaining confirmed that 1,25(OH)2D3 blocked LPS-induced p65 nuclear translocation in RAW264.7 cells. In another recent study we demonstrated that liganded VDR physically interacts with IKKβ protein to disrupt the formation of IKK complex, resulting in blockade of the NF-κB activation pathway [44] (Figure 3). In fact, VDR interacting with regulatory proteins has been documented in a number of pathways as a negative regulatory mechanism for VDR to down-regulate gene transcription [45; 46]. Together our data establish that 1,25(OH)2D3-VDR signaling down-regulates bic transcription by blocking NF-κB activation.

Figure 3.

Mechanism whereby vitamin D-VDR signaling inhibits NF-κB activation. Liganded VDR interacts with IKKβ to disrupt the formation of IKK complex. Consequently, IκBα is stabilized and p65/p50 nuclear translocation is blocked. 1,25VD, 1,25(OH)2D3 or its analogs.

Conclusion

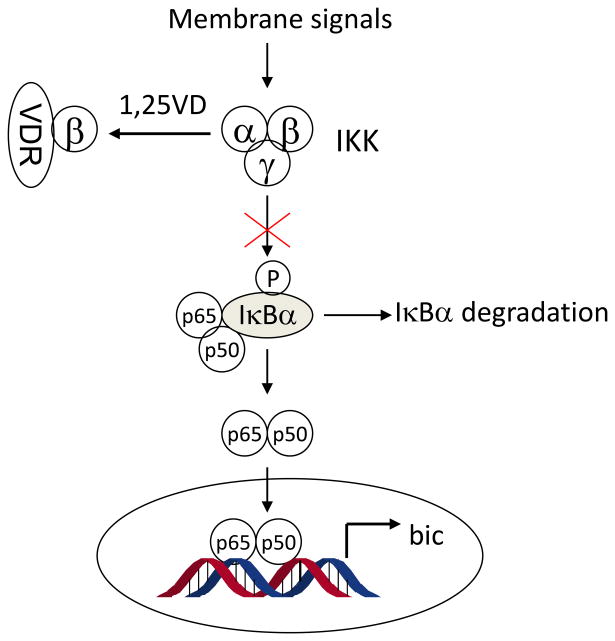

Our recent works reveal a novel microRNA-mediated mechanism whereby vitamin D-VDR signaling suppresses inflammatory response by promoting the negative feedback regulation. In TLR4-mediated innate immunity SOCS1 plays a key role in the negative feedback loop, which keeps immune response from overacting. During endotoxin-induced inflammatory reaction miR-155 rapidly increases to suppress SOCS1 translation, allowing the inflammatory reaction to proceed and sustain without resistance. In the presence of the vitamin D hormone, vitamin D-VDR signaling down-regulates bic gene transcription by blocking NF-κB activation, resulting in reduction of miR-155 synthesis. As a result, the repression of SOCS1 by miR-155 is released, and SOCS1 levels increase, which enhances the negative feedback regulation of inflammatory response (Figure 4). We conclude that this is the molecular basis of a novel anti-inflammatory mechanism whereby vitamin D-VDR signaling limits TLR4-mediated inflammation. This conclusion predicts potential detrimental effects of vitamin D-deficiency, under which condition inflammatory reaction may be unchecked and over-sustained. This may in part explain the association of vitamin D-deficiency and inflammatory disorders in humans [47; 48; 49; 50].

Figure 4.

Mechanism whereby VDR signaling downregulates miR-155 and enhances the negative feedback inhibition of TLR4-mediated inflammatory response. 1,25VD, 1,25(OH)2D3 or its analogs.

As an important regulator in the immune system, miR-155 has multiple targets involved in immune functions. In addition to SOCS1, miR-155 also represses SHIP-1 and C/EBPβ [51; 52], two key negative regulators of IL-6 signaling pathway. Thus vitamin D may also modulate immune response by regulating SHIP-1 and/or C/EBPβ via miR-155. Moreover, miR-155 has been detected in a variety of immune cells including B cells [16], T cells [17], macrophages [18], dendritic cells [19] and hematopoietic progenitor cells [20]. Given the broad functionalities of miR-155, it is possible that vitamin D may regulate the activities of other immune cells through miR-155. In this regard, this work may have opened new avenues to explore various immunomodulatory mechanisms of vitamin D.

Highlights.

VDR deletion leads to hyper inflammatory response to endotoxin

VDR signaling up-regulates SOCS1 via suppressing miR-155

miR-155 mediates vitamin D inhibition of inflammation

1,25(OH)2D3 down-regulates bic/miR-155 transcription via targeting NF-κB

Vitamin D-VDR signaling attenuates TLR-mediated inflammatory response by enhancing the negative feedback regulation

Acknowledgments

Grant support: NIH R01HL085793, R01DK092143.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No authors declare a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haussler MR, Whitfield GK, Kaneko I, Haussler CA, Hsieh D, Hsieh JC, Jurutka PW. Molecular mechanisms of vitamin D action. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92:77–98. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouillon R, Carmeliet G, Verlinden L, van Etten E, Verstuyf A, Luderer HF, Lieben L, Mathieu C, Demay M. Vitamin D and human health: lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocr Rev. 2008;29:726–776. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mora JR, Iwata M, von Andrian UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:685–698. doi: 10.1038/nri2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart PH, Gorman S, Finlay-Jones JJ. Modulation of the immune system by UV radiation: more than just the effects of vitamin D? Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:584–596. doi: 10.1038/nri3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu PT, Stenger S, Li H, Wenzel L, Tan BH, Krutzik SR, Ochoa MT, Schauber J, Wu K, Meinken C, Kamen DL, Wagner M, Bals R, Steinmeyer A, Zugel U, Gallo RL, Eisenberg D, Hewison M, Hollis BW, Adams JS, Bloom BR, Modlin RL. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial response. Science. 2006;311:1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1123933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau V, Nagai Y, Wang Q, Liao J, Tavera-Mendoza L, Lin R, Hanrahan JW, Mader S, White JH. Cutting edge: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J Immunol. 2004;173:2909–2912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gombart AF, Borregaard N, Koeffler HP. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. FASEB J. 2005;19:1067–1077. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3284com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurlek A, Pittelkow MR, Kumar R. Modulation of growth factor/cytokine synthesis and signaling by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3): implications in cell growth and differentiation. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:763–786. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Etten EV, Mathieu C. Immunoregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3): Basic concepts. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Liu W, Sun T, Huang Y, Wang Y, Deb DK, Yoon D, Kong J, Thadhani R, Li YC. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D Promotes Negative Feedback Regulation of TLR Signaling via Targeting MicroRNA-155-SOCS1 in Macrophages. J Immunol. 2013;190:3687–3695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zamore PD, Haley B. Ribo-gnome: the big world of small RNAs. Science. 2005;309:1519–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1111444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winter J, Jung S, Keller S, Gregory RI, Diederichs S. Many roads to maturity: microRNA biogenesis pathways and their regulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:228–234. doi: 10.1038/ncb0309-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tam W, Ben-Yehuda D, Hayward WS. bic, a novel gene activated by proviral insertions in avian leukosis virus-induced lymphomas, is likely to function through its noncoding RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1490–1502. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tam W. Identification and characterization of human BIC, a gene on chromosome 21 that encodes a noncoding RNA. Gene. 2001;274:157–167. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00612-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thai TH, Calado DP, Casola S, Ansel KM, Xiao C, Xue Y, Murphy A, Frendewey D, Valenzuela D, Kutok JL, Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky N, Yancopoulos G, Rao A, Rajewsky K. Regulation of the germinal center response by microRNA-155. Science. 2007;316:604–608. doi: 10.1126/science.1141229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haasch D, Chen YW, Reilly RM, Chiou XG, Koterski S, Smith ML, Kroeger P, McWeeny K, Halbert DN, Mollison KW, Djuric SW, Trevillyan JM. T cell activation induces a noncoding RNA transcript sensitive to inhibition by immunosuppressant drugs and encoded by the protooncogene, BIC. Cell Immunol. 2002;217:78–86. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00506-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1604–1609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610731104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ceppi M, Pereira PM, Dunand-Sauthier I, Barras E, Reith W, Santos MA, Pierre P. MicroRNA-155 modulates the interleukin-1 signaling pathway in activated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2735–2740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811073106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Connell RM, Rao DS, Chaudhuri AA, Boldin MP, Taganov KD, Nicoll J, Paquette RL, Baltimore D. Sustained expression of microRNA-155 in hematopoietic stem cells causes a myeloproliferative disorder. J Exp Med. 2008;205:585–594. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez A, Vigorito E, Clare S, Warren MV, Couttet P, Soond DR, van Dongen S, Grocock RJ, Das PP, Miska EA, Vetrie D, Okkenhaug K, Enright AJ, Dougan G, Turner M, Bradley A. Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science. 2007;316:608–611. doi: 10.1126/science.1139253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eis PS, Tam W, Sun L, Chadburn A, Li Z, Gomez MF, Lund E, Dahlberg JE. Accumulation of miR-155 and BIC RNA in human B cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3627–3632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500613102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kluiver J, Poppema S, de Jong D, Blokzijl T, Harms G, Jacobs S, Kroesen BJ, van den Berg A. BIC and miR-155 are highly expressed in Hodgkin, primary mediastinal and diffuse large B cell lymphomas. J Pathol. 2005;207:243–249. doi: 10.1002/path.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costinean S, Zanesi N, Pekarsky Y, Tili E, Volinia S, Heerema N, Croce CM. Pre-B cell proliferation and lymphoblastic leukemia/high-grade lymphoma in E(mu)-miR155 transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7024–7029. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602266103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Endotoxin tolerance: new mechanisms, molecules and clinical significance. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koeffler HP, Reichel H, Bishop JE, Norman AW. gamma-Interferon stimulates production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 by normal human macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;127:596–603. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(85)80202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichel H, Koeffler HP, Norman AW. Synthesis in vitro of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 by interferon-gamma-stimulated normal human bone marrow and alveolar macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10931–10937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Molecular mechanism in tolerance to lipopolysaccharide. J Inflamm. 1995;45:13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshimura A, Naka T, Kubo M. SOCS proteins, cytokine signalling and immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:454–465. doi: 10.1038/nri2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexander WS. Suppressors of cytokine signalling SOCS in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:410–416. doi: 10.1038/nri818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kinjyo I, Hanada T, Inagaki-Ohara K, Mori H, Aki D, Ohishi M, Yoshida H, Kubo M, Yoshimura A. SOCS1/JAB is a negative regulator of LPS-induced macrophage activation. Immunity. 2002;17:583–591. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagawa R, Naka T, Tsutsui H, Fujimoto M, Kimura A, Abe T, Seki E, Sato S, Takeuchi O, Takeda K, Akira S, Yamanishi K, Kawase I, Nakanishi K, Kishimoto T. SOCS-1 participates in negative regulation of LPS responses. Immunity. 2002;17:677–687. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00449-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujimoto M, Naka T. Regulation of cytokine signaling by SOCS family molecules. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:659–666. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Androulidaki A, Iliopoulos D, Arranz A, Doxaki C, Schworer S, Zacharioudaki V, Margioris AN, Tsichlis PN, Tsatsanis C. The kinase Akt1 controls macrophage response to lipopolysaccharide by regulating microRNAs. Immunity. 2009;31:220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Neill LA, Sheedy FJ, McCoy CE. MicroRNAs: the fine-tuners of Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nri2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Connell RM, Rao DS, Chaudhuri AA, Baltimore D. Physiological and pathological roles for microRNAs in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:111–122. doi: 10.1038/nri2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crespo A, Filla MB, Russell SW, Murphy WJ. Indirect induction of suppressor of cytokine signalling-1 in macrophages stimulated with bacterial lipopolysaccharide: partial role of autocrine/paracrine interferon-alpha/beta. Biochem J. 2000;349:99–104. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gatto G, Rossi A, Rossi D, Kroening S, Bonatti S, Mallardo M. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 trans-activates miR-155 transcription through the NF-kappaB pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:6608–6619. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonizzi G, Karin M. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakanishi C, Toi M. Nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitors as sensitizers to anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:297–309. doi: 10.1038/nrc1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun J, Kong J, Duan Y, Szeto FL, Liao A, Madara JL, Li YC. Increased NF-{kappa}B activity in fibroblasts lacking the vitamin D receptor. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E315–322. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00590.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Z, Yuan W, Sun L, Szeto FL, Wong KE, Li X, Kong J, Li YC. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) targeting of NF-kappaB suppresses high glucose-induced MCP-1 expression in mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2007;72:193–201. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y, Zhang J, Ge X, Du J, Deb DK, Li YC. Vitamin D Receptor Inhibits Nuclear Factor kappaB Activation by Interacting with IkappaB Kinase beta Protein. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:19450–19458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.467670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palmer HG, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Espada J, Berciano MT, Puig I, Baulida J, Quintanilla M, Cano A, de Herreros AG, Lafarga M, Munoz A. Vitamin D(3) promotes the differentiation of colon carcinoma cells by the induction of E-cadherin and the inhibition of beta-catenin signaling. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:369–387. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yuan W, Pan W, Kong J, Zheng W, Szeto FL, Wong KE, Cohen R, Klopot A, Zhang Z, Li YC. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Suppresses Renin Gene Transcription by Blocking the Activity of the Cyclic AMP Response Element in the Renin Gene Promoter. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29821–29830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705495200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loftus EV, Jr, Sandborn WJ. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(01)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loftus EV., Jr Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: Incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–1517. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lim WC, Hanauer SB, Li YC. Mechanisms of Disease: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel disease. Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2005;2:308–315. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gombart AF, Bhan I, Borregaard N, Tamez H, Camargo CA, Jr, Koeffler HP, Thadhani R. Low plasma level of cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (hCAP18) predicts increased infectious disease mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:418–424. doi: 10.1086/596314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Costinean S, Sandhu SK, Pedersen IM, Tili E, Trotta R, Perrotti D, Ciarlariello D, Neviani P, Harb J, Kauffman LR, Shidham A, Croce CM. Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol-5-phosphatase and CCAAT enhancer-binding protein beta are targeted by miR-155 in B cells of Emicro-MiR-155 transgenic mice. Blood. 2009;114:1374–1382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Baltimore D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7113–7118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902636106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]