Abstract

Human omphalocele is a congenital defect of the abdominal wall in which the secondary abdominal wall structures (muscle and connective tissue) in an area centered around the umbilicus are replaced by a translucent membranous layer of tissue. Histological examination of omphalocele development and moreover the staging of normal human abdominal wall development has never been described. We hypothesized that omphalocele is the result of an arrest in the secondary abdominal wall development and predicted that we would observe delays in myoblast maturation and an arrest in secondary abdominal wall development. To look for evidence in support of our hypothesis, we performed a histological analysis of normal human abdominal wall development and compared this to mouse. We also conducted the first histological analysis of two human specimens with omphalocele. In these two omphalocele specimens, secondary abdominal wall development appears to have undergone an arrest around Carnegie Stage 19. In both specimens disruptions in the unidirectional orientation of myofibers were observed in the external and internal obliques, and rectus abdominis but not in the transversus abdominis. These latter findings support a model of normal abdominal wall development in which positional information instructs the orientation of myoblasts as they organize into individual muscle groups.

Keywords: human omphalocele, body wall, muscle development, mouse, human

INTRODUCTION

Giant omphalocele is a congenital defect of the abdominal wall that is characterized by the absence of secondary abdominal wall structures (dermis, fascia, and muscle) in the area of the ventral body wall centered around the umbilicus. This covering is often referred to as a membranous sac, which is a white, translucent layer of tissue (Shoenwolf et al., 2008). Omphalocele is thought to result from an arrest in abdominal wall development prior to final closure of the abdominal wall near the end of the first trimester. Studies in animal models as well as from human genetic screens have implicated a number of genes in the formation of this defect including Rock-1, Pitx2, Igfr-1, Fgfr1 and Fgfr2, Hoxb2 and Hoxb4, Alx-4, AP2 alpha, and Msx1 and Msx2 (Eggenschwiler et al., 1997; Qu et al., 1997; Perveen et al., 2000; Manley et al., 2001; Brewer and Williams, 2004; Ogi et al., 2005; Shimizu et al., 2005; Thumkeo et al., 2005; Nichol et al., 2011). In these models, myoblast migration is impeded and myoblast differentiation is delayed, resulting disorganization of muscle and connective tissue layers, which are components of the secondary abdominal wall (Brewer and Williams, 2004; Ogi et al., 2005; Nichol et al., 2011). Based on this, we hypothesized that in omphalocele embryos, development of the secondary body wall would arrest at early stages that correspond to the specific Carnegie stage (CS) of normal development. Thus, if an arrest occurred at CS 17 (6 weeks gestation) then in an embryo that is 12 weeks into gestation (when the abdominal wall is closed) the architecture of the secondary abdominal wall would be similar if not identical to a CS 17 embryo. However, the staging of secondary abdominal wall development has never been described in humans or mice. In fact, there is limited information about normal abdominal wall development in both species.

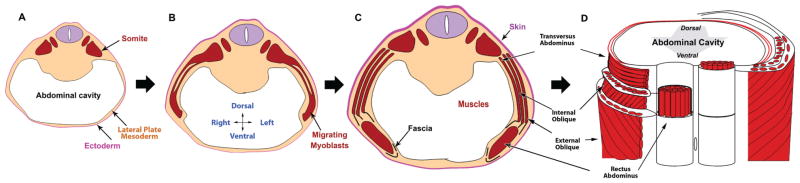

The process is divided into several steps (Shoenwolf et al., 2008). The primary abdominal wall is composed of ectoderm and lateral plate mesoderm (somatopleure) which elongates laterally and “folds” or coalesces at the ventral midline around the umbilicus creating and enclosing the abdominal cavity (Fig. 1A). Myoblasts then migrate out of the myotome into the primary body wall (Fig. 1B) and secondary structures (muscles and connective tissues) begin to form (Fig. 1C). At the completion of secondary abdominal development, the abdominal wall is comprised of four muscle pairs (external obliques, internal obliques, transversus abdominae, and rectus abdominae), their surrounding connective tissues and skin (Fig. 1D). Orientation of myofibers within a given muscle is both unidirectional and distinct from adjacent, ipsilateral muscles and symmetric to the paired muscle on the contralateral side.

Fig. 1.

The general steps of secondary abdominal wall development. (A) The primary abdominal wall joins in the ventral midline creating the abdominal cavity. (B) The myoblasts migrate out of the somites toward the ventral midline. (C) Secondary structures form including individual muscles and connective tissue. (D) A ventral view of the fully developed secondary abdominal wall structures cut transversely to reveal the orientation of muscle fibers within specific groups. Rectus abdominal muscle fibers are seen running vertically. Transversus abdominis fibers are perpendicular to the rectus. The fibers of the internal oblique are at a 45 degree angle to both of these muscles. The external obliques are also at a 45 degree angle to both the rectus and the transversus but are perpendicular to the fibers of the internal oblique.

We set out to look for evidence that omphalocele arises from an arrest in secondary abdominal wall development and to test our hypothesis that the histology of omphalocele would resemble that of the specific CS at which the arrest occurred. To do this, we first established the staging of secondary abdominal wall development in both humans and mice. We found that the timing and sequence of secondary abdominal wall development in humans and mice were similar if not identical between the species.

We then examined two human specimens with omphalocele to determine if their histology resembled specific CSs of normal development, and found that myoblasts failed to reach the ventral midline with delay of myotubes differentiation. The omphalocele embryos also showed disruptions in the spatial relationships between abdominal muscles as well as the interceding connective tissue. These features are consistent with an arrest in development at a CS 18–19, well before completion of normal secondary abdominal wall development. Additionally, disruptions in unidirectional myofiber orientation in muscles closest to the skin and ventral midline were observed suggesting disruptions in a patterning mechanism based on positional information within the primary abdominal wall.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

IACUC approval for these studies was obtained from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public health (P.F.N) and University of Utah (Y.S.). All animals (mouse) were maintained in a clean facility with access to fresh food and water and kept on a 12 hr alternating light/dark cycle. CD-1 outbred mice at from 8 weeks to 6 months were used for mating to obtain embryos. In each experiment, at least five embryos from 3 litters were examined.

Histology

Wild-type breedings were set up and Noon of the day of the plug was considered embryonic day E0.5. Pregnant mice are sacrificed by cervical dislocation in accord to our IACUC protocols. Embryos were harvested at E11.5, E12.5, E13.5, E14.5, E15.5, and E16.5. Whole mount photographs were taken under a dissection microscope. Those E13.5 or greater in age were decapitated shortly after harvest. They were fixed in Bouin’s fixative overnight at 4°C and dehydrated through a series of escalating PBS/Ethanol steps and embedded into Paraffin. Sections were taken a 10-μm thickness. Sections were dewaxed stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin, and cover slipped. Photomicrographs were taken at 20× and 400× using an Olympus® BX41 light microscope and an Olympus® DP20 camera (Tokyo, Japan).

Analysis of Human Specimens

IRB approval was obtained for this study (P.F.N. protocol # m2010-1077). The human embryos examined in this study were from the Kyoto Collection of Human Embryos held in the Congenital Anomaly Research Center of Kyoto University (Matsunaga and Shiota, 1977; Kameda et al., 2012; Nakashima et al., 2012). A series of preserved human embryos were selected [CSs; O’Rahilly and Müller (in press)] 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 23, and 15 weeks gestation) based on availability of transverse histological sections and photomicrographic analysis was performed. Two additional specimens that were identified as having an omphalocele defect (CS 21 and 15 weeks gestations) and had been sectioned were also included. All embryos had already been photographed before sectioning, and serially sectioned at 10-μm thickness for histological examination and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin, Periodic Acid Schiff or Trichrome stains on alternating sections. Photomicrographs were taken using Olympus® BX41 microscope and an Olympus DP20 camera (Tokyo, Japan). As multiple images needed to be taken at high magnification, complete images were reconstructed in Adobe Photoshop® (San Jose, CA) using the merge tool. Angles of each fiber of muscles was examined in transverse sections using Image J and organized from −90° to 90° degree along the dorsoventral axis in Excel.

RESULTS

Staging of Mouse Abdominal Wall Development

E10.5

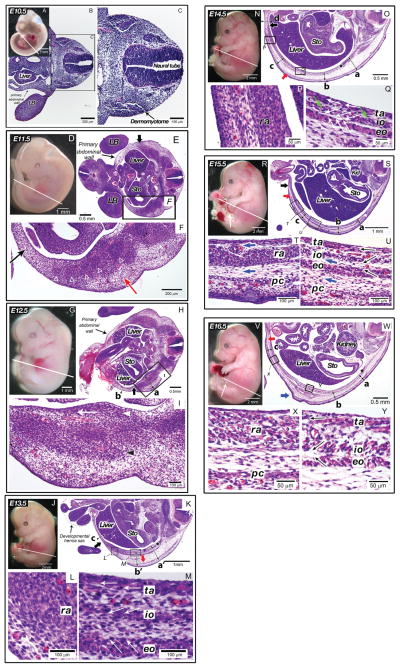

We began our analysis of mouse abdominal wall development at embryonic day E10.5 (Fig. 2A). At this stage the dermomyotome was visible adjacent to the ectoderm (Fig. 2C). The mesoderm of the primary body wall was noncompact and it has already coalesced in the ventral midline to create the abdominal cavity which on the low magnification section was seen to contain the liver (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Histological characteristics of secondary abdominal wall development in the mouse (E10.5–E16.5). In all figures, the right and left sides correspond to the dorsal and ventral orientations of embryos, respectively. (A–C) E10.5 mouse embryo (CS 14). The primary abdominal wall was closed and myoblasts has not reached to the body wall. (A) Whole mount E10.5 mouse embryo. White line indicates plane of sections shown in B and C. (B) Transverse section of the embryo at low magnification. The limb bud (LB) and liver were seen in this view. The primary abdominal wall is indicated by a black arrow. (C) High magnification of area of interest seen in B. The dermomyotome is indicated by a black arrow. (D–F) E11.5 mouse embryo. (CS 16) Myoblasts have migrated half the distance to the midline, but individual muscles were not seen. (D) Whole mount E11.5 mouse embryo. White line indicates plane of section in E and F. (E) Transverse section of E11.5 mouse embryo. The limb buds (LB) and liver and stomach (Sto) were seen in this view. The primary abdominal wall is indicated by a thin black arrow. The leading edge of myoblast migration is indicated by a thick black arrow at the top of this figure. (F) High magnification view of E11.5 mouse embryo abdominal wall. White open triangles indicate areas of condensations that likely represent early ribs. Black and red arrows indicate mesenchyme cells in the primary and secondary body wall, respectively. (G–I) E12.5 mouse embryo. (CS 18) Myoblasts began organizing into separate muscle layers. (G) Whole mount E12.5 mouse embryo. White line indicates plane of section in H and I. (H) Transverse section of the E12.5 mouse embryo. The liver and stomach (Sto) were seen in this view. The primary abdominal wall is indicated by a thin black arrow. The distance of myoblast migration is indicated by a thick black arrow at the bottom of this figure. The thickness of the body wall was measured: a, 750 μm; b, 180 μm. The distance between the external oblique and the dermis was 280 μm. (I) High magnification view of E12.5 mouse embryo abdominal wall. White arrowhead indicates the inner layer of muscle demonstrating unidirectional orientation (white arrow), black arrowhead indicates the outer layer of muscle. (J–M) E13.5 mouse embryo (CS 20). All muscle groups were visualized but the rectus has not segregated from the other muscle groups and migration to the midline was not yet complete. (J) Whole mount E13.5 mouse embryo. White line indicates plane of section in K–M. (K) Transverse section through E13.5 mouse embryo. The liver and stomach (Sto) were seen as is the developmental hernia sac at the umbilicus. Black star indicates rib. Red arrow indicates ventral most point of the panniculus carnosus, black arrow indicates ventral most point of migrating myoblasts. The thickness of the body wall was measured: a′, 667 μm; b′, 628 μm; c, 82 μm. The length of the connective tissues between the external oblique and dermis was 470 μm at both positions of a′ and b′. (L) High magnification view of the rectus abdominis (ra). (M) High magnification view of the transversus abdominis (ta), internal (io) and external obliques (eo). White arrows demonstrate the directional orientation of myoblasts within individual muscle layers. (N–Q) E14.5 mouse embryo (CS 23). The rectus has segregated from the remaining layers, migration to the midline was 90% completed. (N) Whole mount E14.5 mouse embryo. White line indicates plane of section in O–Q. (O) Transverse section through E14.5 mouse embryo. Red arrow indicates ventral most point of the panniculus carnosus, black arrow indicates ventral most point of migrating myoblasts. Black star indicates the rib. The thickness of the body wall was measured: a, 640 μm; b, 366 μm; c, 400 μm; d, 126 μm. (P) High magnification view of the rectus abdominis (ra). (Q) High magnification view of the transversus abdominis (ta), internal (io), and external obliques (eo). White arrows demonstrate directional orientation of myoblasts within individual muscle layers. Green arrows indicate myotubes. (R–U) E15.5 mouse embryo. Migration of secondary abdominal wall structures to the midline was complete. (R) Whole mount E15.5 mouse embryo. White line indicates plane of section. White arrow indicates developmental hernia sac at the umbilicus. White line indicates plane of section in S–U. (S) Transverse section through E15.5 mouse embryo. The liver, stomach (Sto) and kidney (Kid) were seen in this view. Red arrow indicates ventral most point of panniculus carnosus, black arrow indicates ventral most point of the rectus abdominis. White star indicates the rib. The thickness of the body wall was measured: a, 258 μm; b, 350 μm; c, 305 μm. (T) High magnification view of the rectus abdominis (ra) and panniculus carnosus (pc). Myotubes were now abundant within these muscles. The directions of connective tissues between muscles are shown in blue arrows. (U) High magnification view of the transversus abdominis (ta), internal oblique (io), and external oblique (eo), and panniculus carnosus (pc). Myotubes were abundant within these muscles with the unidirectional orientation (black arrows). The directions of connective tissues between muscles are shown in blue arrows. (V–Y) E16.5 mouse embryo. The closure of the developmental hernia at the umbilicus has occurred complete. (V) Whole mount E16.5 mouse embryo. White line indicates plane of section in W–Y. White arrow indicates the umbilicus after reduction of developmental hernia sac. (W) Transverse section through E16.5 mouse embryo. The liver, stomach (Sto) and kidney were seen in this view. Red arrow indicates ventral most point of panniculus carnosus, blue arrow indicates condensation of a tissue rostral to the hind limb. Black star indicates the rib. The thickness of the body wall was measured: a, 312 μm; b, 351 μm; c, 291 μm. (X) High magnification view of the rectus abdominis (ra) and panniculus carnosus (pc). Unidirectional orientation within the myotubes was seen in the rectus abdominis. (Y) High magnification view of transversus abdominis (ta), internal oblique (io), external oblique (eo). Unidirectional orientation of myotubes was seen in each layer (arrows).

E11.5

By E11.5 (Fig. 2D) secondary abdominal wall development has started. Myoblasts was migrating ventrally into the primary body wall (Fig. 2E). The distance migrated ventrally by the myoblasts was approximately half of the distance to the ventral midline (Fig. 2E, thick black arrow). The myoblasts have not yet formed separate inner and outer layers (Fig. 2F). The lateral plate mesoderm adjacent to the migrating myoblasts was thicker and more compact (Fig. 2F, red arrow) than the lateral plate mesoderm of the more ventral primary abdominal wall (Fig. 2F, black arrow).

E12.5

As the mouse embryo reaches E12.5 in development (Fig. 2G), the ventral most myoblasts have progressed modestly toward the ventral midline compared to the previous stage (Fig. 2H, thick black arrow). The second body wall region that contains myoblasts became thicker (780 μm, Fig. 2H, position a) than the primary body wall 180 μm, Fig. 2H, position b). There now appears to be distinct inner and outer layers of tissue. The innermost tissue layer (Fig. 2I, white arrowhead) began to exhibit unidirectional orientation to its cells (Fig. 2I, white arrow) where as the outer layer (Fig. 2I, black arrowhead) did not exhibit any unidirectional orientation.

E13.5

By E13.5 (Fig. 2J) all five the principal muscles of the mouse abdominal wall were observed (rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, and panniculus carnosus) (Fig. 2K). Complete segregation of the rectus abdominis from the transversus abdominis and obliques has not occurred. The panniculus carnosus was formed in the dorsal half of the abdominal wall adjacent to the skin (Fig. 2K, red arrow). This muscle layer is absent in humans except in the face, neck, nipple, and groin regions. The myoblasts have migrated approximately three fourths of the distance to the ventral midline (Fig. 2K, black arrow). The connective tissue between the muscle layers and dermis comprised the majority of the thickness of the secondary abdominal wall with the layer between the panniculus carnosus and external oblique being the thickest of these layers (470 μm at the positions a′ and b′ in Fig. 2K). A close examination of the histology showed directional organization of the myoblasts in the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis (Fig. 2M, white arrows).

E14.5

At E14.5 (Fig. 2N), with the exception of the panniculus carnosus (Fig. 2O, red arrow), the migration of the myoblasts to the ventral midline was almost complete (Fig. 2O, black arrow). Directional organization of the myoblasts was observed in the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis (Fig. 2Q, white arrows) and myotubes appeared to be forming within these muscle groups (Fig. 2Q, green arrows). The connective tissue layers comprise the majority of the thickness of the abdominal wall with the layer between the panniculus carnosus and external oblique similar to those in the specimen at E13.5. In the area over the rectus abdominis, the connective tissue layers are thicker than in the previous stage as the myoblasts migrated into this area (Fig. 2P).

E15.5

At E15.5 (Fig. 2R) the panniculus carnosus has reached the ventral midline (Fig. 2S, red arrow). The myotubes were abundant in all five of the muscle layers with the unidirectional orientation in all layers (Fig. 2T, U, black arrows). The developmental herniation of the intestines at the umbilical cord has not been reduced into the abdominal cavity (Fig. 2R white arrow). Now the body wall had a uniform thickness throughout (250–350 μm, Fig. 2S, at positions a–c). The thickness of the connective tissue layers was less than in earlier stages, particularly the layer between the panniculus carnosus and external oblique (Fig. 2S, U). High magnification views showed that unlike the adjacent muscles, the orientation of all connective tissue layers was oriented in a dorsal–ventral direction (Fig. 2T, U, blue arrows).

E16.5

At E16.5, the developmental herniation was completely reduced (Fig. 2V, white arrow) and the unidirectional orientation of myotubes within the rectus (Fig. 2X, white arrows), the obliques, and transversus abdominis was again evident (Fig. 2Y, arrows). The connective tissue layer between the rectus and panniculus carnosus is less dense than at E15.5 (Fig. 2X).

Staging of Human Abdominal Wall Development

CS 14 (E33)

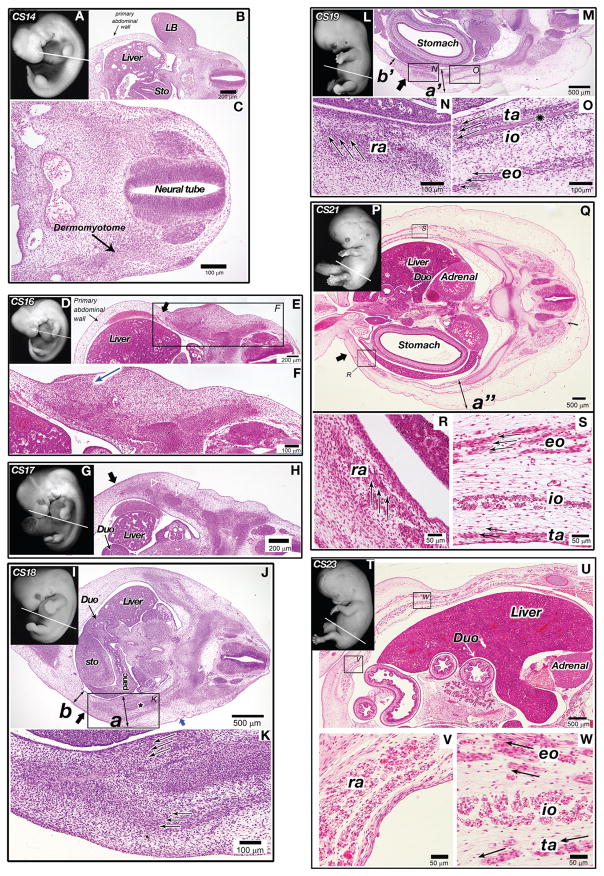

We began analysis of human abdominal wall development at CS 14 (Fig. 3A). The mesoderm of the primary body wall was noncompact and it has coalesced in the ventral midline to create the abdominal cavity in which liver and stomach were seen at low magnification (Fig. 3B). Development of the CS 14 embryo was similar to the E10.5 mouse embryo and the dermomyotomes that are derived from somites have been formed (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Histological staging of secondary human abdominal wall development CS 14–23. In all figures, the right and left sides correspond to the dorsal and ventral orientations of embryos, respectively. (A–C) Human embryo at CS 14 (day 32). The primary abdominal wall was closed and myoblasts has not reached to the body wall. (A) Whole mount photo of a human embryo at CS 14 demonstrating plane of section (white line). (B) Transverse section at the level of the white line in A. Dermomyotome was formed. The limb buds (LB), liver and stomach (Sto) were seen in this view. The primary abdominal wall is indicated by the black arrow. (C) High magnification image demonstrating the dermomyotome and the neural tube. (D–F) Human embryo at CS 16 (day 37). Myoblasts have migrated quarter the distance to the midline. (D) Whole mount photo of a human embryo at CS 16 demonstrating plane of section (white line). (E) Transverse section at the level of the white line in D. The liver was seen in this view. The primary abdominal wall is indicated by the thin black arrow. Thick black arrow at the top of this figure indicates ventral most point of migrating myoblasts. (F) High magnification image of area of interest in image E. An arrow indicates the condensed lateral plate mesoderm. (G and H) Human embryo at CS 17 (day 41). Myoblasts have migrated half the distance to the midline. (G) Whole mount photo of a human embryo at CS 17 demonstrating plane of section (white line). (H) Low magnification photomicrograph of the CS 17 human embryo at the level of a white line in G. The duodenum (Duo) and liver were seen in this view. Black arrow indicates the ventral most point of myoblast migration. Open white arrowheads mark condensations that are likely early ribs. (I–K) Human embryo at CS 18 (day 44). Myoblasts began organizing into separate muscle layers. (I) Whole mount photo of a human embryo at CS 18 demonstrating plane of section (white line). (J) Low magnification photomicrograph of the CS 18 human embryo at the level of the white line in I. The liver, stomach (Sto), duodenum (Duo) and pancreas (panc) were all seen in this view. Myoblasts were organizing into individual layers (area inside the box). Extent of ventral migration indicated by a black arrow. A black star indicates an early rib. The thickness of the body wall measurements were 500 μm (a) and b: 260 μm (b). The connective tissue in the dorsal regions comprises half the thickness of the secondary abdominal wall (blue arrow). (K) High magnification image from image J. Black arrows indicate early directional organization of migrating myoblasts. (L–O) Human embryo at CS 19 (day 47.5). All muscle groups were separated including the rectus abdominis. (L) Whole mount photo of a human embryo at CS 19 demonstrating plane of section (white line). (M) Low magnification photomicrograph at the level of the white line in L. The stomach was seen in this view. Abdominal wall demonstrating that the myoblasts have organized into four distinct muscle layers. Extent of ventral migration indicated by black arrow. The body wall thicknesses were 500 μm (a′) and 260 μm (b′). (N) High magnification view of the rectus muscle at CS 19 demonstrates unidirectional orientation of myoblasts (black arrows). (O) High magnification view of the external oblique (eo), internal oblique (io) transversus abdominis (ta). Black arrows indicate unidirectional organization of myoblasts. The starred structure between the transversus and internal oblique is likely an early nerve. (P–S) Human embryo at CS 21 (day 52). Myoblasts have reached the ventral midline and myotubes were now present and oriented uniformly within all muscle groups. (P) Whole mount photo of a human embryo at CS 21 demonstrating plane of section (white line). (Q) Low magnification photomicrograph at the level of the white line in P. The liver, stomach, adrenal gland and duodenum (Dou) were all seen in this view. Myoblast migration to the midline was complete and the ventral most boundary of the rectus abdominis is indicated by a black arrow. The distance between the external oblique and the dermis was 700 μm and the total thickness of the body wall is 1200 μm at the position a″. (R) High magnification view of the rectus abdominis (ra). Black arrows indicate directional organization of myotubes. (S) High magnification view of the external oblique (eo), internal oblique (io) transversus abdominis (ta). Black arrows indicate directional organization of myotubes which were abundant at this stage. (T–W) Human embryo at CS 23 (day 56.5). Distinct layers were formed in the rectus abdominis and myotube formation became more prominent in all muscles. (T) Whole mount photo of a human embryo at CS 23 demonstrating a plane of section (white line). (U) Low magnification photomicrograph at the level of the white line in T. Liver, kidney and duodenum (Dou) are all seen in this view. (V) High magnification view of the rectus abdominis (ra) in which myotubes are abundantly seen. (W) High magnification view of the external oblique (eo), internal oblique (io) transversus abdominis (ta). Again myotubes were seen in this view. Black arrows represent orientation of the connective tissues between muscle layers.

CS 16 (E40)

At CS 16, the extent or distance of the migration was about 25% of the hemicircumference of the abdominal cavity (Fig. 3D, E). As seen in the mouse, the lateral plate mesoderm has become more condensed and thicker in the area around the myoblasts (Fig. 3E, black arrow in F). The primary abdominal wall ventral to this region was thinner and less dense (Fig. 3E, thin arrow). This suggests that not only myoblasts but also the connective tissue may migrate into the primary body wall or may have active cell proliferation.

CS 17 (E42)

The histological appearance of the human abdominal wall at CS 17 (Fig. 3G, H) was strikingly similar to the mouse at E11.5 with cells now having migrated approximately 50% of the distance to the ventral midline (Fig. 3H, thick arrow). Inner and outer layers were not discernible yet.

CS 18 (E44)

At CS 18 (Fig. 3I) the separation of the myoblasts into distinct inner and outer layers became evident (Fig. 3J), and appeared to be equivalent to those in the E12.5 mouse embryo in terms of overall histological appearance and distance migrated by the myoblasts (Fig. 3J, thick arrow). The myoblasts in both the inner and outer layers began to exhibit unidirectional orientation (Fig. 3K, arrows). The abdominal wall was thicker in the region where secondary structures were forming (a: 500 μm, Fig. 3J) compared with the primary body wall region (260 μm, Fig. 3J). In the more dorsally positioned regions, the outermost layer of connective tissue comprised approximately half of this thickness (Fig. 3J, blue arrow).

CS 19 (E48)

Segregation of the myoblasts into four distinct muscle groups was evident by CS 19 (Fig. 3L) with unidirectional orientation of myoblasts (Fig. 3M, N). The myoblasts migrated over half of the distance to the ventral midline (Fig. 3M, thick black arrow). The abdominal wall remains thickest (a′: 550 μm, Fig. 3M) in the area where the muscles migrated and again the outermost layer of connective tissue comprises approximately half of the total thickness of the abdominal wall in this region. In contrast the primary abdominal wall that is ventral to the migrating myoblasts was noticeably thinner (b′: 210 μm, Fig. 3M). Unlike the mouse where the rectus is not segregated from the other muscles until reaching the midline (compare E13.5: Fig. 2J–M to Fig. 3L–O), the human rectus was completely separated after migrating over half the distance to the midline.

CS 21 (E54)

By CS 21 (Fig. 3P), the myoblasts have reached the ventral midline (Fig. 3Q, thick black arrow) and myotubes were present and oriented uniformly within all muscle groups (Fig. 3R, S, black arrows). The rectus abdominis formed distinct bundles of muscle indicating that development and differentiation of this muscle were more prominent in humans than in mice. Similar to the mouse embryo at E14.5, the connective tissue layers comprised the majority of the thickness of the abdominal wall at CS 21. Furthermore, the outermost layer of connective tissue accounted for the majority of this thickness (700 μm for the distance between the external oblique and the dermis and the total thickness of the body wall is 1200 μm at the position a″).

CS 23 (E58)

At CS 23 (Fig. 3T) the rectus muscle was forming 2 or 3 distinct layers (Fig. 3U, V) and myotube orientation remained uniform in all muscles (Fig. 3V, W). The external oblique and internal oblique started to expand in terms of thickness whereas the transversus remained a thin layer of muscle. The thickness of the connective tissue was reduced similar to that in the mouse at E15.5. The orientation of connective tissue layers in the obliques and transversus abdominis was dorsal to ventral (Fig. 3W, arrows).

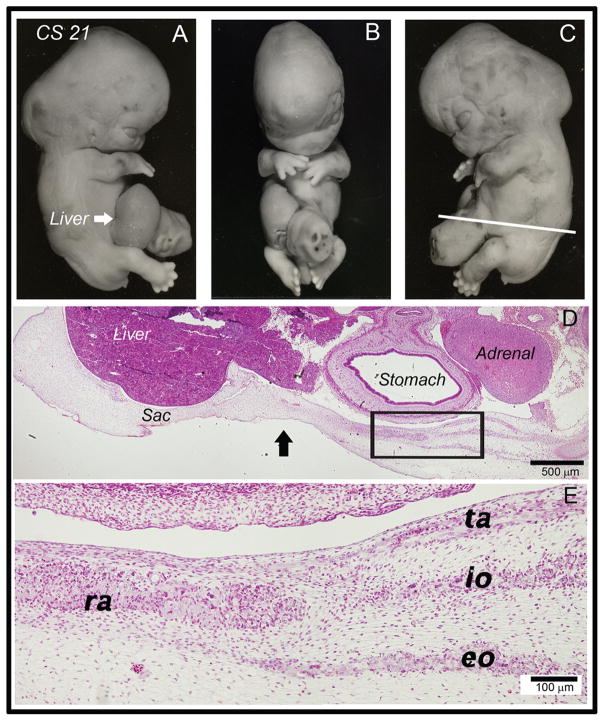

Human omphalocele at CS 21

Examination of a CS 21 embryo with an omphalocele (Fig. 4A–C) demonstrated the right side of the sac was ruptured and the liver protruded (Fig. 4A, white arrow). The embryo also showed nuchal swelling. This swelling is frequently observed in normal embryos at CS 21 and it seems to occur as the embryonic head becomes upright at this developmental stage. There was the liver present within the sac and four distinct muscle groups were observed in the body wall (Fig. 4D, E). The myoblasts migrated only 50–60% of the distance towards the ventral midline whereas in a normal embryo at this stage migration is almost complete (compare to Fig. 3Q–S). Additionally, the internal and external obliques and transverses abdominis were shortened in comparison to those in a stage-matched normal embryo (compare to Fig. 3Q). In areas where the myoblasts have migrated into the primary abdominal wall, the thickness of the abdominal wall was increased significantly, as was seen in normal development. High power examination of the myoblasts demonstrated a lack of unidirectional alignment within both the rectus abdominis and external oblique, which by this point should be uniform in normal development (Compare Fig. 4E to Fig. 3R, S). Additionally, the myoblasts have not begun to differentiate into myotubes, which would normally occur by CS 21. These findings suggest an arrest in myoblast migration and a delay in differentiation into myotubes. The connective tissue layers did not exhibit the unidirectional dorsal ventral orientation seen in the stage matched normal embryo. In fact, the appearance of the secondary abdominal wall structures was very similar to that of the normal human embryo at CS 19 (Fig. 3M–O).

Fig. 4.

Histological analysis of a human omphalocele at CS 21. (A–C) Whole mount photographs of a CS 21 human embryo with omphalocele. Rupture of the sac has occurred on the right and the liver was protruding (white arrow). White line in (C) indicates plane of section for (D) and (E). (D) Low magnification view of a section through this specimen at the level of the white line. The right and left sides correspond to the dorsal and ventral orientations of embryos, respectively. The liver, adrenal gland and stomach are all seen in this view. A large portion of the liver is seen within the developmental hernia sac (area to the left of the black arrow). Four distinct layers of muscle developed. (E) High magnification view of the rectus abdominis (ra), external oblique (eo), internal oblique (io) transversus abdominis (ta). Myoblasts have not yet differentiated into myotubes. There was a lack of unidirectional orientation of myoblasts in the rectus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique layers.

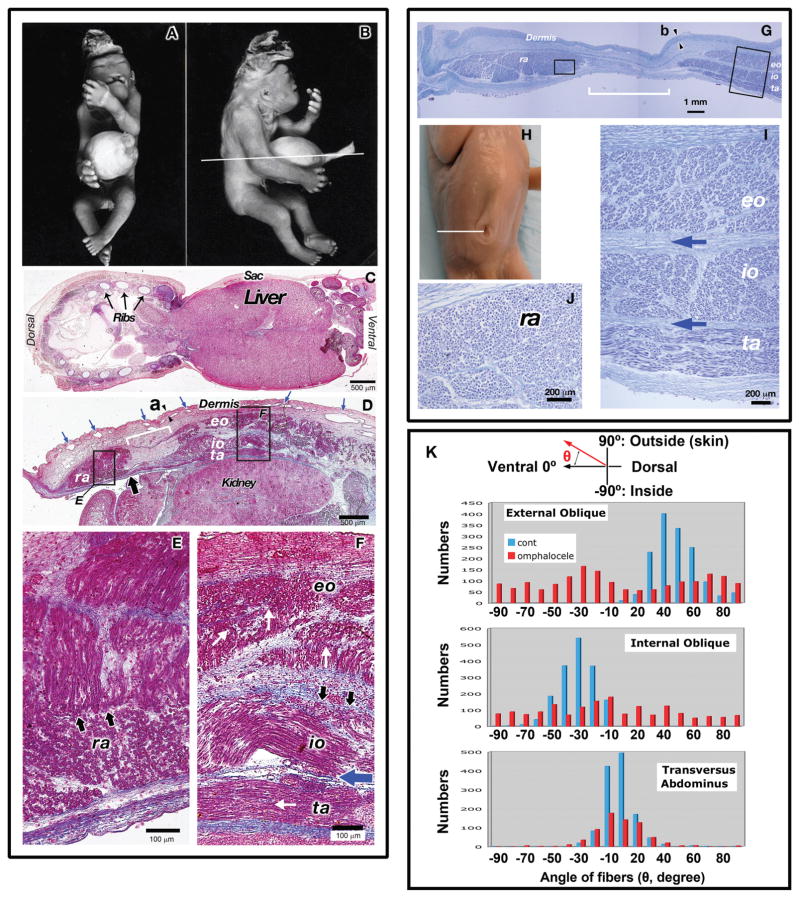

Human Omphalocele at 15 weeks G.A

This is an extremely abnormal fetus which along with a giant omphalocele manifests several findings consistent with trisomy 13 including exencephaly and bilateral cleft lip (Fig. 5A, B). This phenotype with both exencephaly and an abdominal wall defect has also been observed in AP2 alpha−/− mutant mice (Schorle et al., 1996; Brewer and Williams, 2004). A low magnification photomicrograph demonstrated a large portion of the liver inside of the omphalocele sac (Fig. 5C). In comparison to the normal fetus at the same stage (Fig. 5G–J), the thickness of the dermis was dramatically reduced (control: 350 μm at the position b in Fig. 5G vs. omphalocele: 80 mm at the position a in Fig. 5D) and the vascular plexus underlying the dermis was excessive (Compare Fig. 5D, blue arrows to G). The internal oblique in the omphalocele specimen had a sinusoidal pattern likely due to contraction (Fig. 5D). A similar phenomenon was seen in the transversus abdominis of the stage matched normal fetus (Fig. 5I) although it is much milder. In the omphalocele specimen, high magnification views showed groups of muscle fibers running perpendicular to other fibers in the rectus abdominis (Fig. 5E, black arrows), external oblique (Fig. 5F, white arrows) and in limited regions of the internal oblique (Fig. 5F, black arrows). A normal fetus at this point in gestation exhibits unidirectional myofiber orientation in each muscle group (Fig. 5I, J). This disorganization in muscle fiber was more obvious when the directions of each muscle fiber were examined by measuring their angles along the dorsoventral orientation in transverse sections (Fig. 5K). In the control fetus (blue bars in Fig. 5K), the external, internal obliques, and transversus abdominis have clear peaks of the angles at 40°, −30°, and 15° degrees, respectively, indicating that most fibers run in parallel. Conversely, in the omphalocele fetus (red bar in Fig. 5K), external and internal obliques showed broad distribution of angles without clear peaks. For the rectus abdominis, almost all fibers ran in parallel along the craniocaudal orientation in control (2560/2566, 99.8%); however, 40.0% of fibers were unaligned in the omphalocele fetus (1287/3221). The dorsal–ventral distance from the obliques and transverses to the rectus was much shorter in the omphalocele specimen compared to the control (0.75 mm vs. 4.6 mm, respectively; white brackets in Fig. 4D, H). In fact the muscle fibers of the transversus abdominis lay underneath the rectus adjacent to the abdominal cavity (Fig. 5D, black arrow). Furthermore, the transversus abdominis, internal and external obliques were disorganized and have failed to develop as continuous layers of muscle in the dorsal to ventral orientation. In addition to defects in muscle layers, the connective tissues were also affected in the omphalocele embryo. Thickness of the connective tissue layer between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis was largely reduced in the omphalocele specimen (Fig. 5F, blue arrow) in comparison to the control (Fig. 5I, blue arrows) suggesting incomplete segregation of these muscle layers during development. Interestingly, the connective tissue between the transverses abdominis and the body cavity developed a uniform layer with unidirectional fibers similar to the normal fetus (Fig. 5K), which coincide with less influence on the transverses abdominis in the omphalocele specimen.

Fig. 5.

Histological analysis of a human omphalocele at 15-weeks gestational age. In all figures of sections, the right and left sides correspond to the dorsal and ventral orientations of embryos, respectively. (A–F) Human omphalocele at 15-weeks gestational age. (A–B) whole mount photos (A and B) of a 15-week gestation fetus with a giant omphalocele. White line indicates plane of section for Fig. 4C–F. (C) Low magnification of abdominal wall of omphalocele specimen demonstrating liver within the omphalocele sac. The ribs, liver, and sac are indicated. (D) Intermediate magnification view of abdominal wall on transverse section demonstrating the presence of all four principal muscle layers of the abdominal wall. The kidney was seen in this view. The ventral most extent of the transversus abdominis was seen encroaching underneath the rectus abdominis (brad black arrow). The dermis developed as a thinner layer (80 μm between arrowheads at the position “a”) and many vascular plexi developed underlying the dermis (blue arrows). (E) High magnification view of the rectus abdominis (ra) demonstrating myofibers running perpendicular to each other (black arrows). (F) High magnification view of the transversus abdominis (ta), internal oblique (io), and external oblique (eo). Loss of unidirectional orientation of myofibers in the internal oblique is indicated by the black arrows and by the white arrows in the external oblique. The blue arrow indicates a lack of interceding connective tissue and separation between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique. (G–J) Normal human fetus at 15-weeks gestational age. (G) Low magnification of abdominal wall of normal 15-week gestational age fetus. There was a clear separation of between the transversus abdominis and the rectus abdominis as indicated by the white brackets. The thickness of the dermis was 350 μm between arrowheads at the position “b.” (H) Whole mount photo of a normal 15-week gestational age fetus. White line indicates plane of section for Figures G, I and J. (I) High magnification view of the internal oblique (io), external oblique (eo), and transversus abdominis (ta). Orientation of myofibers within each muscle layer appears unidirectional. Blue arrows indicate interceding connective tissue between muscle layers. (J) High magnification view of the rectus abdominis demonstrating unidirectional orientation of myofibers. (K) The directions of muscle layers in both normal and omphalocele samples. The directions of each muscle fiber were examined by measuring their angles along the dorsoventral orientation in transverse sections as shown in the top cartoon. Blue and red columns denote angles in control and omphalocele muscles, respectively. In the normal fetus, fibers of the external and internal obliques ran at the angle of 40° and −30°, respectively along the dorsoventral orientation. Fibers in the transverses abdominis showed a 10° angle. In the omphalocele fetus, the transverses abdominis had a clear peak of the angle similar to control one whereas the internal and external obliques did not have a significant peak of angles and ran at a random orientation. Numbers of fibers that did not have any angle on sections (vertical to transverse sections: run along cranial–caudal axis) were follows: in control, external oblique: 69; internal oblique: 48; transverses adbdominus: 44. In omphalocele fetus: external oblique: 355; internal oblique:354; transverses abdominis: 2.

DISCUSSION

We first made a comparative analysis of normal abdominal wall development between the human and mouse by focusing on muscle differentiation. Next, we performed an analysis of human abdominal wall development to establish a developmental clock for the timing of this arrest. These studies suggest that human omphalocele is the result of an arrest in secondary abdominal wall development, and histologically resembles the specific CS at which the arrest occurred.

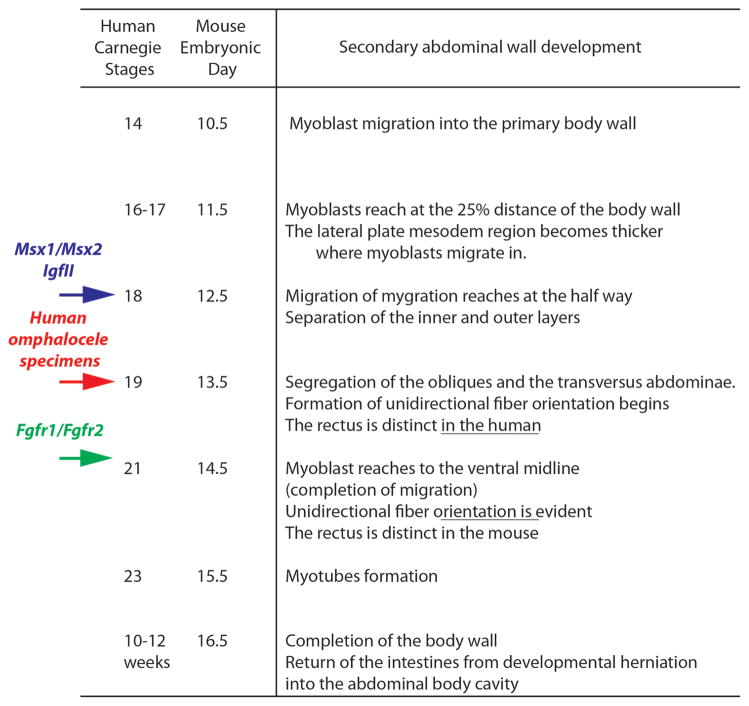

Secondary abdominal wall development in both the human and mouse observed in this study is summarized in Fig. 6. The developmental timing of the secondary body wall is very similar between these two models except for the rectus abdominis. In the human, the rectus is distinct at CS 19 (corresponding to E13.5 mouse embryos) whereas the rectus is separated from other muscle layers at E14.5 in the mouse embryo. In addition to this delay of development in the mouse rectus, organization of the rectus is more evident in the human than the mouse. In the human, the rectus abdominis formed distinct bundles of muscle at CS 21 (corresponding to E14.5 mouse embryos) although the bundles were not clear in the mouse even at the later stages (E16.5). The more rapid and prominent development of the rectus abdominis in humans versus mice likely underscores the importance of this muscle for upright, bipedal locomotion. The panniculus carnosus, an additional muscle layer in the mouse that is not present in the human abdominal wall, was formed all the way to the midline by E16.5. Thereafter, the developmental herniation of the intestines has been reduced into the abdominal cavity from the umbilical cord. This corresponds to the temporal window of weeks 10–12 in humans. From these results we can derive a developmental clock of abdominal wall development for both humans and mice (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Comparative staging of secondary abdominal wall development in the human and mouse. Histological correlation between mouse embryonic day and human CS from Figs. 3 and 4 is presented. Red arrow indicates the approximate timing of arrest in secondary abdominal wall development of the two omphalocele specimens in Figs. 5 and 6. Blue arrow indicates the timing of arrest in Msx1/Msx2 and IGF-II mutants based on published data in which muscle layers stop migration at the half way and no muscle layers are segregated, resulting giant omphalocele (Eggenschwiler et al., 1997). Green arrow indicates the timing of arrest in Fgfr1/Fgfr2 mutants in which the rectus, obliques and transversus abdominis are all present and fails to reach the midline, resulting small omphalocele (Nichol et al., 2011).

Based on the staging of normal abdominal wall development it appears that both omphalocele specimens underwent an arrest around CS 19. First, in both specimens myoblasts have segregated into four abdominal wall muscle groups. Analysis of the CS 21 omphalocele specimen demonstrates that the myoblasts have migrated only 50–60% of the distance towards the ventral midline. Second, the spacing between the rectus abdominis and other muscles is minimal in both omphalocele specimens. Finally, the CS 21 omphalocele specimen has not yet completed myotube formation, indicating that differentiation of myoblasts is delayed as well. These three observations suggest that an arrest in secondary abdominal wall development and myoblast migration occurred in these two omphalocele specimens at around CS 19 (Fig. 6, red arrow).

We can apply the information from these studies to determine the timing of the arrest in abdominal wall development seen in mouse models of omphalocele. For example, homozygous mutation of Msx1/Msx2 results in a giant omphalocele (Ogi et al., 2005). Based on the reported histology of this defect, the myoblasts have formed inner and outer layers but have failed to progress further in development. This indicates that an arrest occurred around E12.5 or CS 18 (Fig. 6, blue arrow). Similar histological findings are present in mouse embryos that over express IGF-II, which also results in a giant omphalocele (Eggenschwiler et al., 1997). In Fgfr1/Fgfr2 compound mutants, the rectus, obliques, and transversus abdominis are all present but the formation of the panniculus carnosus is incomplete and fails to reach the midline. The layer of connective tissue between the panniculus carnosus and external oblique remains thick (Nichol et al., 2011). This suggests that an arrest occurred between E13.5 and E14.5 (Fig. 6, green arrow).

The organization and patterning of the abdominal wall muscles suggest the influence of positional information that directs the segregation of muscle groups and the unidirectional arrangement of myofibers within each muscle group. In omphalocele embryos, as a result of an arrest in abdominal wall development, myoblasts failed to reach their target destinations in the abdominal wall, and then muscles could not develop unidirectional fibers except for the transversus abdominis. Additionally, the spatial relationships between the obliques and the transversus abdominis appear to be altered with loss or thinning of connective tissue layers between these muscles. Interestingly, in the omphalocele embryos the connective tissue adjacent to the transversus abdiminus normally developed, which may support relatively normal development of the transversus abdominis. These observations suggest a model in which orientation of myoblasts and myofibers is determined by positional information from connective tissues, which may be derived from the primary body wall or somatopleure. However, it is still unknown whether the primary cause of the omphalocele is in myoblasts or in the primary abdominal wall. Work in animal models suggests either or both mechanisms could be at work here. Mutations in Rock1 (Shimizu et al., 2005; Thumkeo et al., 2005) affect organization of actin, and mutations in Msx1/Msx2 (Ogi et al., 2005) directly affect myoblast development. On the other hand, mutations in AP2-alpha affect ectoderm and neural crest development (Brewer and Williams, 2004), and mutations of Fgfr1/Fgfr2 omphalocele seem to primarily affect ectoderm and dermal development (Nichol et al., 2011, in press). Thus, defects within the somatopleure or the myoblasts ability to respond to that information appear to lead to the formation of this defect. This question would be addressed by tissue specific mutants that cause omphalocele phenotypes in mice in future.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: American College of Surgeons Faculty Research Fellowship 2006-2008; Grant number: NIH KO81K08DK087854-01; Grant sponsor: March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation (FY08-427); Grant number: NICHD (R01HD066121).

The authors thank Gary Schoenwolf for useful suggestions, and Lisa Benko for developing macro in Excel to organize data on fiber angles.

LITERATURE CITED

- Brewer S, Williams T. Loss of AP-2alpha impacts multiple aspects of ventral body wall development and closure. Dev Biol. 2004;267:399–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggenschwiler J, Ludwig T, Fisher P, Leighton PA, Tilghman SM, Efstratiadis A. Mouse mutant embryos overexpressing IGF-II exhibit phenotypic features of the Beckwith-Wiedemann and Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndromes. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3128–3142. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameda T, Yamada S, Uwabe C, Suganuma N. Digitization of clinical and epidemiological data from the Kyoto Collection of Human Embryos: maternal risk factors and embryonic malformations. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2012;52:48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2011.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley NR, Barrow JR, Zhang T, Capecchi MR. Hoxb2 and hoxb4 act together to specify ventral body wall formation. Dev Biol. 2001;237:130–144. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga E, Shiota K. Holoprosencephaly in human embryos: epidemiologic studies of 150 cases. Teratology. 1977;16:261–272. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420160304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima T, Hirose A, Yamada S, Uwabe C, Kose K, Takakuwa T. Morphometric analysis of the brain vesicles during the human embryonic period by magnetic resonance microscopic imaging. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2012;52:55–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2011.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol PF, Corliss RF, Tyrrell JD, Graham B, Reeder A, Saijoh Y. Conditional mutation of fibroblast growth factor receptors 1 and 2 results in an omphalocele in mice associated with disruptions in ventral body wall muscle formation. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.09.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogi H, Suzuki K, Ogino Y, Kamimura M, Miyado M, Ying X, Zhang Z, Shinohara M, Chen Y, Yamada G. Ventral abdominal wall dysmorphogenesis of Msx1/Msx2 double-mutant mice. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2005;284:424–430. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rahilly R, Müller F. Developmental stages in human embryos: including a revision of Streeter’s “Horizons” and a survery of the Carnegie collection. Washington, D.C: Carnegie Institution of Washington publication; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Perveen R, Lloyd IC, Clayton-Smith J, Churchill A, van Heyningen V, Hanson I, Taylor D, McKeown C, Super M, Kerr B, Winter R, Black GC. Phenotypic variability and asymmetry of Rieger syndrome associated with PITX2 mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2456–2460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu S, Niswender KD, Ji Q, van der Meer R, Keeney D, Magnuson MA, Wisdom R. Polydactyly and ectopic ZPA formation in Alx-4 mutant mice. Development. 1997;124:3999–4008. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorle H, Meier P, Buchert M, Jaenisch R, Mitchell PJ. Transcription factor AP-2 essential for cranial closure and craniofacial development. Nature. 1996;381:235–238. doi: 10.1038/381235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, Thumkeo D, Keel J, Ishizaki T, Oshima H, Oshima M, Noda Y, Matsumura F, Taketo MM, Narumiya S. ROCK-I regulates closure of the eyelids and ventral body wall by inducing assembly of actomyosin bundles. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:941–953. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoenwolf G, Bleyl SB, Brauer PR, Francis-West PH. Larsen’s human embryology. 4. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier-Churchill Livingstone; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thumkeo D, Shimizu Y, Sakamoto S, Yamada S, Narumiya S. ROCK-I and ROCK-II cooperatively regulate closure of eyelid and ventral body wall in mouse embryo. Genes Cells. 2005;10:825–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]