Abstract

Medical education is evolving to include more community-based training opportunities. Most frequently, third-and fourth-year medical students have access to these opportunities. However, introducing community-based learning to medical students earlier in their training may provide a more formative experience that guides their perspectives as they enter clinical clerkships. Few known courses of this type exist for first-year medical students.

Since 1998, the Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) has required first-year students to take a yearlong Community Health Course (CHC) that entails conducting a community health needs assessment and developing, implementing, and evaluating a community health promotion intervention. In teams, students conduct health needs assessments in the fall, and in the spring they develop interventions in response to the problems they identified through the needs assessments. At the end of each semester, students present their findings, outcomes, and policy recommendations at a session attended by other students, course faculty, and community stakeholders.

The authors describe the course and offer data from the course’s past 11 years. Data include the types of collaborating community sites, the community health issues addressed, and the interventions implemented and evaluated. The MSM CHC has provided students with an opportunity to obtain hands-on experience in collaborating with diverse communities to address community health. Students gain insight into how health promotion interventions and community partnerships can improve health disparities. The MSM CHC is a model that other medical schools across the country can use to train students.

Medical school curricula are constantly evolving to prepare young physicians-in-training to be able to provide high-quality health care within dynamic medical systems that often struggle to balance care for poor and underserved communities with economic solvency. In this context, teaching medical students community medicine means teaching them to employ public health approaches while caring for individuals. Students do not learn through traditional curricula to incorporate community concerns into health care delivery. In recent years, medical educators have placed more attention on equipping medical students and residents with the tools to incorporate the community in their delivery of primary health care.1–5 However, medical curricula are still not fully adequate for preparing students to meet the demands that they will face in serving poor, underserved communities.

One approach to teaching future clinicians the skills they need to serve communities is “service-learning.”6,7 Service-learning is a teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities. Service-learning combines service objectives and learning objectives with the intent that the activity will change both the recipient and the provider of the service. Research has shown that students engaged in service-learning showed an increase in the degree to which they felt aware of community needs, believed they could make a difference, and were committed to service in the future,8 and communities involved in service-learning have shown decreased numbers of people engaging in risky behaviors.9 The changes in the provider occur through the combination of service tasks and structured opportunities that link the service task to self-reflection, self-discovery, and the acquisition and comprehension of values, skills, and knowledge content.

Recognizing the significance of service-learning in medical education, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) revised its accreditation standards in July 2008 to include a new standard on service-learning, stating that medical schools should not only make available sufficient opportunities for medical students to participate in service-learning activities but also encourage and support student participation.10 The LCME suggests that medical schools provide information about available service-learning opportunities, develop service-learning opportunities in partnership with relevant communities, offer students credit for participating in service-oriented activities and courses, and hold presentations or public forums to highlight and recognize service-learning activities.

Learning the tools of community health needs assessment and health promotion and having an opportunity to exercise these skills can prepare students to deliver care to communities as well as individual patients.2 Community health needs assessments are used to identify the strengths and needs of the community, to establish community health priorities, and to facilitate collaborative action planning directed at improving community health status and quality of life.11 Some examples of community health needs assessment tools include focus groups and surveys. Health promotion is the process of enabling people to increase their control over and improve their own health.12 We believe that educating physicians early in their training and giving them an opportunity to practice their skills in a service environment may be one factor leading to the greater incorporation of public health in health care delivery. Whereas students learn primary care medicine in medical school, exposure to community settings is often sparse in the first two years of medical education, which are largely focused on the basic sciences. We feel that early exposure to or familiarity with community medicine may inspire more physicians to specialize in primary care or community medicine or to integrate community-based medicine principles into their chosen specialty.

Some medical trainees have the opportunity to participate in community experiences in their clinical clerkships, in electives during the third and fourth years of medical school, or through residency programs.13–15 However, few courses of this type exist for preclinical medical students, and studies that document the immersion of medical students in the community during the first two years of their training are lacking in the literature. The purpose of this article is to describe a novel course that both uses the service-learning construct to expose preclinical medical students to the community setting and allows students to analyze the health problems of the community and to design and implement an intervention to address identified community problems.

Morehouse School of Medicine (MSM) was founded to train students for careers as primary care physicians who will practice in medically underserved areas among populations of minorities and/or populations with low socioeconomic status. MSM’s curriculum reflects the institution’s commitment both to support the underserved urban and rural populations in Georgia and across the nation and to address primary health care needs through programs in education, research, and service. MSM requires the Community Health Course (CHC) for all first-year medical students. Originally taught as a series of individual, discrete classroom lectures, it became a community-based service-learning course in 1998.16 The course engages first-year medical students, faculty members, and community-based organizations in service-learning and community service.

The CHC at MSM

The CHC is a two-semester course that provides students with the opportunity to analyze the health, health problems, and the delivery of health services in underserved communities. The course’s topics of study comprise community health analysis, health-related behavior, and community health promotion. Instructional methods include hands-on community activities in a small-group setting, group discussions, reading and writing assignments, and introductory lectures. Students receive classroom instruction in two 3-hour sessions at the beginning of each semester. As a foundation for the health promotion activities in the course, the two fall lectures focus on viewing the community as a patient (“Clinical Community Health”) and review theory on how the physician will diagnose and treat the patient, that is, the community. This CHC conceptual framework is the converse of the well-known “community-oriented primary care” model, which uses public health concepts to guide the actions of clinicians.17,18 In the CHC clinical concepts guide the actions of students engaged in the practice of public health. That is, students gather subjective and objective data, compile a problem list, and formulate and carry out a therapeutic plan, all in the manner of a clinician treating a patient.16 To prepare students to adapt evidence-based health promotion activities for their communities, fall lecture topics also include performing searches of the medical literature and instruction on critiquing articles. For the remainder of the fall semester, students use a team-based approach for the community assessments and the required presentations (Table 1). In the spring semester, students receive instruction on writing program objectives, on constructing and understanding logic models, and on designing, implementing, and evaluating a health promotion intervention. Spring lectures also address the relationship between public health and public policy.

Table 1.

Timeline of the Community Health Course at the Morehouse School of Medicine

| Timing | Activity or activities—Students… |

|---|---|

| Fall semester | |

| Weeks 1–3 | …attend lectures |

| Weeks 4–5 | …begin meeting at community site and conduct key informant interviews |

| Weeks 6–8 | …conduct focus group interviews and plan surveys |

| Week 7 | …submit their journal critiques |

| Weeks 8–9 | …conduct their surveys and start their community engagement activities |

| Weeks 10–11 | …conduct their data analyses and share the results of their needs assessment with community liaisons and leaders |

| Weeks 12–13 | …prepare their presentations and papers |

| Week 13 | …submit their papers |

| Week 14 | …give their presentations to course faculty, community stakeholders, and other students |

| Spring semester | |

| Week 1 | …attend lectures |

| Weeks 2–12 | …plan and revise their interventions |

| Weeks 2–13 | …conduct community engagement activities |

| Weeks 6–13 | …conduct their community interventions |

| Weeks 14–16 | …conduct their data analyses and prepare their final papers and presentations |

| Week 16 | …submit their final papers and give their presentations to course faculty, community stakeholders, and other students |

Groups of 10 to 14 students and two faculty facilitators are assigned to community sites at the start of each academic year. Classes occur at community sites that the faculty facilitators of each small group have selected either through their own prior experiences or through referrals from other faculty members or community contacts. Faculty select sites on the basis of each site’s involvement with and commitment to low-income and underserved populations, the site’s geographic location (located in metropolitan Atlanta), the site administration’s willingness to facilitate involving its staff and the community it serves in the health needs assessment and intervention, the availability of a community liaison who can serve as a primary contact for the course faculty and students, and the availability of on-site weekly meeting space for the course faculty and students. Each site’s community liaison agrees to work with the faculty facilitators and students for the entire year. These community liaisons may be, for example, a school principal or guidance counselor or the director or program manager of a community organization. The faculty facilitators are health professionals with experience in community health. At least one facilitator in each group has an MD degree, and the other has a PhD or a master’s degree in public health or a related discipline.

Small-group instruction emphasizes access and barriers to health services, team collaboration, project evaluation, community service, health promotion, and disease prevention. Each week, students meet for a three-hour session at their assigned community sites to complete course objectives. The course meetings are factored into the students’ curriculum schedule and do not interfere with the time that students spend in their other required courses. Students are responsible for arranging and organizing their weekly course activities (course activities described below), while faculty leaders serve as group facilitators, guiding groups toward completion of weekly tasks. In addition to completing the actual assessment activities in the fall semester and implementing the intervention activities in the spring semester, the students spend weekly course time planning these activities. During the weeks of planning, dedicated course time also allows the students to interact with community representatives and provide community service. In the CHC, we refer to these interactions with the community and/or community representatives as “community engagement activities.” As a group, the students determine the focus of their community engagement activities; the focus is largely site dependent. For example, groups assigned to schools or after-school programs frequently participate in tutoring. In keeping with the principles of service-learning,6 the students reflect on their experiences through scheduled journal entries and group discussions.

Table 1 provides a timeline of course activities. During the fall semester, faculty facilitators guide students through the community needs assessment methodology by engaging the students in a variety of assessment activities. The assessment begins with a “windshield survey”—that is, the students conduct a visual assessment while they drive through the community. The drive allows them the opportunity to make subjective and objective evaluations that include descriptions of the community and any evidence of trends, stability, or changes that may contribute to the health of the population. Other fall semester activities include student-conducted key informant interviews, (i.e., interviews with integral community stakeholders) and, usually following these, focus groups and community surveys. Although all students in the course must complete the same components of the needs assessment, faculty facilitators encourage them to be creative in their approach to doing so. Sometimes students collect other information—for instance, anthropometric (i.e., height and weight) data on elementary school children.

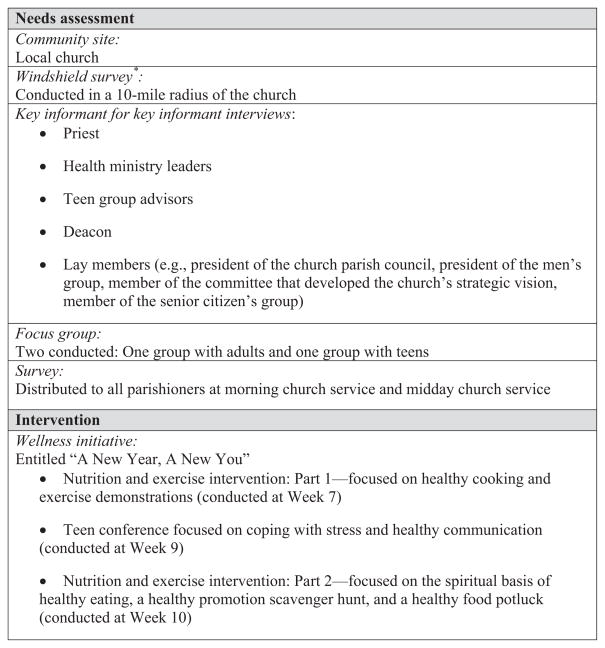

Students continue working in their small groups at community sites during the spring semester, planning, implementing, and evaluating a health promotion intervention that addresses one or more of the community health issues identified during the fall semester. The students begin by revisiting the needs assessment to determine components for their spring intervention. They write objectives for the intervention, using the SMART model: Their objectives must be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time bound. As with the needs assessments, creativity is paramount in designing interventions at sites that have been long-standing community partners. Because students must design a community intervention based on their needs assessment, they may not merely continue the work of previous students. If the needs assessment dictates an expansion on previous students’ work, the faculty facilitators challenge the students to be creative in designing an intervention that is unique yet effective in meeting the community’s needs. Students also design an evaluation of their intervention. In most instances, they use brief pretest and posttest surveys to assess knowledge change, but faculty encourage students to also collect satisfaction and/or process data. Chart 1 provides a sample student needs assessment and intervention from the MSM CHC.

Chart 1. Sample Student Needs Assessment and Intervention From the Morehouse School of Medicine Community Health Course.

* A windshield survey is an activity during which students drive through the community whose needs they plan to assess in order to observe and do an initial observation-only-based assessment.

Student Assessment

Faculty facilitators assess student learning and service through multiple-choice examinations, fall and spring semester group papers, fall and spring semester presentations, class participation, and completion of a reflection journal. All students in the group receive the same grade for the group papers and presentations, but students receive individual grades for class participation, journal entries, and their performance on examinations. Students complete three reflection journal entries each semester; in each journal entry, they answer predetermined questions (e.g., “Describe your experience at your community site,” “What were your initial perceptions?”, “What are some of the general stereotypes or misconceptions you’ve had?”, and “Has your experience at your site supported or refuted these stereotypes?”). Faculty facilitators read the reflection journals of the students in their group. Although the students do not receive subjective comments on their responses, they do receive a grade (complete or incomplete) for answering the questions. The multiple-choice examinations take place once per semester and are based on the introductory lectures that students receive at the start of each semester. Lecturers submit three to four questions per lecture. The two faculty facilitators assigned to each group decide their students’ participation grades through consensus. Participation grades are based on weekly attendance, contribution to weekly discussions and course activities, and interaction with colleagues and community partners. All 10 to 14 students in a group contribute to the group papers, but they are divided into smaller subgroups of two or three students for the presentations. The papers are limited to 3,000 to 3,750 words, excluding tables, figures, and appendices. All of the fall papers and presentations include a description of the community needs assessment and detail

community demographics and assets,

morbidity and mortality data,

socioeconomic factors that impact health, and

a summary of the leading health-related community concerns including the consequences of these public health concerns and the local resources available to the community

The spring semester papers and presentations offer descriptions and evaluations of the student-conducted interventions. Each semester, the students give their presentations (of 20 minutes, followed by a 5- to 10-minute question-and-answer period) to an audience composed of other students, course faculty, and community stakeholders.

Development of the Program

As in most U.S. medical schools, MSM had a required lecture-based course for first-year medical students that included a focus on biostatistics, epidemiology, and health disparities. It included lectures given by MSM faculty and faculty from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 1991, MSM received a grant from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to expand this course. The grant proposal was written based on the Area Health Education Centers (AHEC) program model, which included partnerships between medical schools and communities. AHEC’s mission is to enhance access to quality health care, particularly primary and preventive care, by improving the supply and distribution of health care professionals through community/academic educational partnerships.19 The U.S. Congress developed the AHEC program to recruit, train, and retain a health professions workforce committed to underserved populations.20 With the support of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation grant, the course designers created the original iteration in conjunction with faculty and students from local nursing schools, a theological center, and a school of social work. Although its interdisciplinary nature was a strength, the course experienced several challenges, including the difficulties of identifying community faculty who could design educational lectures of graduate school quality, coordinating multiple presentations while avoiding redundant material, and identifying community presenters who understood the course’s relevance to medical school education. In 1998, the course coordinator and faculty redesigned the course using the service-learning construct and emphasizing the training of only medical students. The redesigned course received funding from the Corporation for National and Community Service. Group leaders are primarily faculty from the Department of Community Health and Preventive Medicine. Over the years, the course faculty has expanded to include one faculty member from the MSM Department of Pediatrics who has extensive community-based experience and several staff members from public health organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A Review of the Community Projects

In the first 11 years of the CHC (1999–2010), over 500 students conducted 56 community interventions—all in metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia. The students established partnerships with the Atlanta Housing Authority, the Boys and Girls Club of Metro Atlanta, Atlanta Public Schools (grades K–12), Headstart, and other smaller grassroots organizations (e.g., churches and neighborhood groups). The two leading health problems the students identified through their health needs assessments were the prevalence of violence and substance abuse (usually identified as comorbid by the community and thus considered a single problem in this analysis [12 assessments]) and the lack of community development (including unemployment, deteriorating housing, and lack of security [12 assessments]). Other leading health problems identified in the health needs assessments included low literacy rates (10 assessments), obesity and nutrition (8 assessments), chronic diseases such as asthma (8 assessments) and hypertension (3 assessments), and adolescent sexual health (3 assessments). Interventions included educational programs, health fairs, and policy initiatives. Some examples of interventions include dental, physical fitness, and parent education workshops, tutoring sessions to address the low literacy levels, and sexual health education workshops for teenagers. No data are available regarding the effect of the CHC on student perceptions during clinical preceptorships or after graduation; however, anecdotal experience and informal feedback suggest that students refer to their CHC experience if/when they choose primary care residencies and that many graduates integrate community service into their practice.

The Significance of Preclinical Community Health Training

This description of the CHC and review of the first 11 years of CHC data suggest that a medical school course focused on community health and service-learning can expose students to community needs assessments and health promotion interventions in a variety of community settings. When incorporated into the medical school curriculum, a CHC can provide an opportunity for medical students to obtain hands-on community engagement experiences. These courses can provide medical students with the knowledge and skills to assess the health of the community and to collaborate with community partners to improve their health.

A CHC can also expose medical students to the common health issues (e.g., poor nutrition/obesity, substance abuse, and a lack of sexual health education/resources) experienced by adults, adolescents, and children in various communities. Many of the problems the students diagnose each semester also mirror the leading health indicators associated with Healthy People 2010.1,21 These indicators reflect the major health concerns in the United States at the beginning of the 21st century. These concerns are important public health issues, and their significance as relevant health disparities is reflected by the fact that the students ascertained the necessity for interventions for similar problems each year.

Several organizations, including the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the Healthy People Curriculum Task Force convened by the Association for Prevention Teaching and Research (formerly the Association of Teachers of Preventive Medicine), and the Association of Academic Health Centers, have delineated standards for integrating population health into the training of health professions students.22,23 The AAMC has asserted that physicians must collaborate with other health professionals and individuals representing a wide variety of community agencies to use systematic approaches for promoting, maintaining, and improving the health of individuals and populations.23 Through participating in the CHC, MSM students collaborate both with peers and with community members and work with a team. We feel that through the course they learn skills that ease their transition into clinical rotations as upper-level medical students and residents, and we hope they will gain proficiencies that may help them function better as physicians as the medical model moves toward multidisciplinary approaches to patient management. By performing needs assessments and designing interventions for underserved communities, students in the CHC address the AAMC’s objective that medical students understand the economic, social, and cultural factors that contribute to the conditions that impact health.23 The assessments of community needs and strengths as well as the interventions—both integral parts of the CHC—also address the Healthy People Curriculum Task Force’s Community Aspects of Practice component,22 which is designed to reflect both clinical prevention and population health.

Service-learning opportunities for medical students are becoming more common; as mentioned, the LCME now mandates that they be made available for students who wish to experience them. MSM’s CHC differs from most of these in that it is required of all first-year students (rather than offered as an elective) and thus introduces all students, including those who would not have pursued it otherwise, to a community health experience. Further, where required courses or clerkships do exist, either they focus on “community diagnosis” alone24 (or conversely, they require a community project without the needs assessment component25) or they are classroom-based courses that are closely tied to epidemiology and traditional population health experiences.26 We are not aware of any other required course in a U.S. or Canadian medical school that provides the full spectrum of community assessment, intervention, and evaluation for first-year medical students.

Over the span of the CHC, the partnerships with the community have enabled us to mobilize more than 500 medical students to address the health disparities of underserved youth and adults by providing responsive health promotion intervention projects throughout metropolitan Atlanta. Each year, the community sites have responded very favorably to the students. Community sites typically return each year to participate in the program, even though none of the sites, community members, or administrators receive compensation or honoraria for participating. Existing organizations (i.e., parent auxiliaries and parent–teacher organizations at schools) at the community sites have sought opportunities to collaborate with the students, frequently scheduling their activities to coincide with the student-planned interventions. The community sites receive, at no cost, the results of the community needs assessments, and they benefit from an intervention designed by students in response to that assessment, but they receive no financial benefits other than the nominal budget ($500–$600) that each group uses to support the assessments and interventions.

We feel that MSM students and faculty serve as role models to the youth and young adults in the community; for example, for more than four years, students in the CHC have implemented a series of life skills, substance abuse, and sexual health education workshops for youth who live in public housing. Following the end of the course, some of the medical students have continued their relationships with the youth whom they mentored. We also hope that community partners feel more empowered to make health decisions and to become advocates for their own health. Evaluations from student interventions reveal short-tem behavior changes such as increased physical activity and making healthier food choices. We hope that these behaviors continue in the long term. Through the course, MSM has strengthened its partnerships with Atlanta community organizations and remains poised to respond to the developing needs of the community.

CHC Funding and Support

The course is faculty-intensive; at least eight faculty members devote a half-day nearly every week to it. Institutional (i.e., MSM) support has been important, and grant funding from the Corporation for National and Community Service and the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) has provided additional support. HRSA funds the AHEC program; the MSM AHEC program is 1 of 54 nationally. The Atlanta AHEC program has helped implement the course through support of community sites and by offering student travel (mileage) reimbursement.

Opportunities for Enhancement

Opportunities for enhancing the MSM CHC include improving the small-group dynamic by increasing the number of faculty and decreasing the number of students in each group. This would allow students a more individualized experience. However, the current economic climate makes this difficult. As mentioned, grant funding has supported the course since its inception, but funding opportunities are becoming scarcer, and greater institutional financial commitment has become a necessary consideration. Although effective and easily implemented educational programs such as this course may contribute to improving the education of future physicians, further study is needed to assess student and community perceptions of the course as well as its long-term effectiveness. Additional research is also needed to investigate the impact that the CHC has on community health status, the continuity or sustainability of student interventions, the specialties chosen by CHC medical students, the types of communities in which they choose eventually to practice, and the degree to which they use the knowledge and skills gained from their CHC experiences.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Meryl McNeal and the staff of the Center for Community Health and Service-Learning at the Morehouse School of Medicine. The authors also wish to thank Dr. George Rust and the staff in the Faculty Development Program at the Morehouse School of Medicine.

Funding/Support: The Morehouse School of Medicine Community Health Course has been funded in part by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and the Corporation for National and Community Service.

Footnotes

Ethical approval: The Community Health Course was not evaluated in this manuscript, so IRB approval was not obtained.

Previous presentations: The authors (A.B., Y.N., and D.B.) gave a poster presentation with information about the Morehouse School of Medicine Community Health Course on February 22, 2007, at the American College of Preventive Medicine “Preventive Medicine 2007” meeting in Miami, Florida.

Other disclosures: Dr. Blumenthal serves on the board of directors of the Southeastern Primary Care Consortium/Atlanta Area Health Education Center, which provided some financial support for the course. He receives no compensation for serving on this board.

Contributor Information

Dr. Ayanna V. Buckner, Department of Community Health and Preventive Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

Dr. Yassa D. Ndjakani, Department of Community Health and Preventive Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

Ms. Bahati Banks, Office of Institutional Advancement & Marketing and Communications, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

Dr. Daniel S. Blumenthal, Department of Community Health and Preventive Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

- 1.Magill MK, Quinn R, Babitz M, Saffel-Shrier S, Shomaker S. Integrating public health into medical education: Community health projects in a primary care preceptorship. Acad Med. 2001;76:1076–1079. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200110000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nickens H. It’s about time. The medicine/public health initiative. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16(3 suppl):20–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cashman SB, Anderson RJ, Weisbuch JB, Schwarz MR, Fulmer HS. Carrying out the medicine/public health initiative: The roles of preventive medicine and community-responsive care. Acad Med. 1999;74:473–483. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199905000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paterniti DA, Pan RJ, Smith LF, Horan NM, West DL. From physician-centered to community-oriented perspectives on health care: Assessing the efficacy of community-based training. Acad Med. 2006;81:347–353. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carney JK, Hackett R. Community–academic partnerships: A “community-first” model to teach public health. [Accessed June 10, 2010];Education for Health. 2008 21(1) Available at: http://www.educationforhealth.net/publishedarticles/article_print_166.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seifer SD. Service-learning: Community–campus partnerships for health professions education. Acad Med. 1998;73:273–277. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199803000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohan CP, Mohan A. HealthSTAT: A student approach to building skills needed to serve poor communities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:523–531. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melchior A. Summary Report: National Evaluation of Learn and Serve America. Waltham, Mass: Brandeis University, Center for Human Resources; 1999. [Accessed July 6, 2010]. Available at: http://www.learnandserve.gov/pdf/lsa_evaluation.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirby D. Emerging Answers: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. [Accessed June 10, 2010];LCME Accreditation Standards. IS-14-A. Available at: http://www.lcme.org/functionslist.htm.

- 11.Manitoba Health. [Accessed July 2, 2010];Community Health Needs Assessment Guidelines. Available at: http://www.chssn.org/En/pdf/networking/community%20health%20assessment.pdf.

- 12.World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion; Ottawa. 21 November 1986; [Accessed July 2, 2010]. WHO/HPR/HEP/95.1. Available at: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrus NC, Bennett NM. Developing an interdisciplinary, community-based education program for health professions students: The Rochester experience. Acad Med. 2006;81:326–331. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mareck DG, Uden DL, Larson TA, Shepard MF, Reinert RJ. Rural interprofessional service-learning: The Minnesota experience. Acad Med. 2004;79:672–676. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIntosh S, Block RC, Kapsak G, Pearson TA. Training medical students in community health: A novel required fourth-year clerkship at the University of Rochester. Acad Med. 2008;83:357–364. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181668410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blumenthal DS, Jones A, McNeal M. Evaluating a community-based multiprofessional course in community health. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2001;14:251–255. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kark SL. The Practice of Community-Oriented Primary Health Care. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Art B, De Roo L, De Maeseneer J. Towards unity for health utilising community-oriented primary care in education and practice. [Accessed June 10, 2010];Education for Health. 2007 20(2) Available at: http://www.educationforhealth.net/publishedarticles/article_print_74.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National AHEC Organization. [Accessed June 30, 2010];AHEC Mission. Available at: http://www.nationalahec.org/About/AHECMission.asp.

- 20.National AHEC Organization. [Accessed June 30, 2010];About Us. Available at: http://www.nationalahec.org/About/AboutUs.asp.

- 21.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Nov, 2000. [Accessed June 10, 2010]. Leading health indicators? Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/document/html/uih/uih_4.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allan J, Barwick TA, Cashman S, et al. Clinical prevention and population health: Curriculum framework for health professions. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Medical School Objectives Writing Group. Learning objectives for medical student education—Guidelines for medical schools: Report I of the Medical School Objectives Project. Acad Med. 1999;74:13–18. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199901000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blacklow RS, Boex JR, Keck CW. A required clerkship in community medicine. Acad Med. 1995;70:449–450. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199505000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chamberlain LJ, Wang NE, Ho ET, Banchoff AW, Braddock CH, Gesundheit N. Integrating collaborative population health projects into a medical student curriculum at Stanford. Acad Med. 2008;83:338–344. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318166a11b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finkelstein JA, McMahon GT, Peters A, Cadigan R, Biddinger P, Simon SR. Teaching population health as a basic science at Harvard Medical School. Acad Med. 2008;83:332–337. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318166a62a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]