Abstract

Context

Schizophrenia remains a highly disabling disorder, but the specific determinants and pathways that lead to functional impairment are not well understood. It is not known whether these key determinants of outcome lie on one or multiple pathways.

Objective

This study evaluated theoretically-based models of pathways to functional outcome starting with early visual perception. The intervening variables were previously established determinants of outcome drawn from two general categories: ability (i.e., social cognition and functional capacity) and beliefs / motivation (i.e., defeatist beliefs, expressive and experiential negative symptoms). We evaluated an integrative model in which these intervening variables formed a single pathway to poor outcome.

Design

This was a cross-sectional study that applied structural equation modeling to evaluate the relationships among determinants of functional outcome in schizophrenia.

Setting

Assessments were conducted at a Veterans Administration (VA) Medical Center.

Participants

One hundred ninety one clinically-stable outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were recruited from the community.

Results

A measurement model showed that the latent variables of perception, social cognition, and functional outcome were well-reflected by their indicators. An initial untrimmed structural model with functional capacity, defeatist beliefs, and expressive and experiential negative symptoms had good model fit. A final trimmed model was a single path running from perception to ability to motivational variables to outcome. It was more parsimonious and had better fit indices than the untrimmed model. Further, it could not be improved by adding or dropping connections that would change the single path to multiple paths. The indirect effect from perception to outcome was significant.

Conclusions

The final structural model was a single pathway running from perception to ability to beliefs / motivation to outcome. Hence, both ability and motivation appear to be needed for community functioning, and can be modeled effectively on the same pathway.

Schizophrenia treatment research has moved well past management of psychotic symptoms to the more ambitious, and to the patient more personally meaningful, goal of “recovery”. In general, recovery refers to achievement of independent living, vocational or educational activities, and satisfying interpersonal relationships 1, 2. To achieve recovery, it is first necessary to identify the key determinants of poor functioning that interfere with successful adaptation. Functional outcome generally refers to the degree of success that a person has with social connections, vocational pursuits, and degree of independent living. Several determinants have been identified, with considerable focus on neurocognition and negative symptoms 3-6. However, other factors, including perception, social cognition, functional capacity, and defeatist beliefs also influence functional success achieved by people with schizophrenia 7-10. The goal of the current study is to evaluate how well data from a large sample of patients fit a single pathway model that runs from visual perception through intervening variables to functional outcome.

Determinants of functional outcome in schizophrenia can be grouped into three general categories: 1) perception, 2) ability, and 3) beliefs / motivation. Perception constitutes an early-stage determinant for outcome 7, 11-14 and can include measures of visual or auditory processing. In this study, we examined early visual perception assessed with measures of visual masking. Starting an outcome model with perception (as opposed to later stages like neurocognition) has advantages for interpretation because perceptual variables have rather direct and established ties to neural processes, and they are relatively less influenced by later processes 11, 15. Hence, early perceptual variables in a model are more likely to influence later variables instead of the other way around.

Performance-based measures from social cognition, neurocognition, and functional capacity can be called measures of ability 16. Social cognition refers to mental processes that underlie social interactions, including perceiving, interpreting, managing, and generating responses to socially relevant stimuli, including intentions and behaviors of others 17, 18. Patients with schizophrenia consistently show impairment across a range of social cognitive tasks 19, and a recent review found that social cognition was a mediator between non-social neurocognition and functional outcome in 14 of 15 studies that evaluated such a role 20. We previously found social cognition to be a mediator between perception and functioning 7, 8, and the current study uses a larger, and entirely independent, sample to examine this question more thoroughly. Neurocognition (i.e. non-social measures of cognition, including memory, attention, reasoning and problem solving, and speed of processing) was not included in the current data set because the focus of the project was visual perception, but it has been a consistent determinant of outcome in several literature reviews 5, 6. Functional capacity (also called competence) refers to the ability to demonstrate activities of daily living or social communications in a simulated setting 21, 22 and it has been found to act as a mediator between neurocognition and functional outcome 9, 10.

Beliefs and motivational factors include negative symptoms, which are highly consistent correlates of daily functioning 3, 23. Negative symptoms are a multifaceted construct comprised of two separable sub-domains: expressive symptom (affective flattening and alogia) and experiential symptoms (avolition/apathy and anhedonia/asociality) 24. Negative symptoms are often linked to motivational factors because they are associated with measures of intrinsic motivation 25 and experiential negative symptoms, in particular, are largely defined in terms of motivation 26.

Beyond identifying determinants, there is a substantial challenge of mapping the interactive pathways through these variables that lead to poor functional outcome. Theories can guide this process, but they have tended to focus on segments of the outcome pathway instead of running all the way from perception to outcome. For example, some “cascade” models have linked early auditory and visual perception to social cognition 8, 11. These theories posit that poor formation of visual and auditory percepts contributes to problems in higher-level processing, such as social cognition.

In addition, a promising theoretical development in understanding negative symptoms and their role in functioning comes from Beck and colleagues. This theory proposes that ability and functional outcome are indirectly related through a causal pathway involving dysfunctional attitudes 27, 28. According to this model, reduced ability leads to discouraging life circumstances, and these discouraging experiences engender negative attitudes and self-beliefs. These dysfunctional attitudes, in turn, contribute to decreased motivation and interest that are seen clinically as different types of negative symptoms. Although several types of dysfunctional attitudes have been considered 29-31, support for this model comes primarily from studies examining, “Defeatist performance beliefs,” which are overly generalized negative beliefs about one's ability to successfully perform tasks 32. Defeatist performance beliefs are endorsed more strongly by individuals with schizophrenia than healthy controls, and correlate with negative, but not positive, symptom severity, even after accounting for depression 29, 33-35. Furthermore, defeatist beliefs can mediate the relation between ability and negative symptoms 33, 34. Thus, there is growing support for this novel conceptualization of negative symptoms proposed by Beck and colleagues.

A key unresolved question in this area is whether measures of ability (e.g., cognition) and measures of motivation (e.g., negative symptoms) act independently upon functional outcome, or whether they are part of a single pathway. In other words, there could be two independent paths to functional outcome, one based on ability (what one can do) and the other on motivation (what one wants to do). Alternatively, there could be a single path in which ability helps to determine motivation (as proposed by Beck et al.). Data are ambiguous on this question; some studies suggest negative symptoms lie on a separate pathway from cognition 9, 36 and others suggest it lies on the same pathway as perceptual or ability measures 7, 33. A formal test of this question requires a large sample and a broad, multifaceted range of measures, including key intervening variables.

Adequate evaluation of pathways to functional outcome requires statistical modeling approaches such as structural equation modeling (SEM) instead of traditional hypothesis-testing approaches. SEM requires relatively large sample sizes and theoretically-based models of outcome to guide the process. We started by evaluating a single path model because it is consistent with both our previous empirical work 7, 34 and the theoretical work of Beck and colleagues 27, 33. It is also the most parsimonious starting model. Evaluation of a single path with SEM provides information regarding whether the model would be improved by modifying it into two or more paths.

Methods

Participants

One hundred and ninety one patients were recruited from community residences and from outpatient treatment clinics at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Patients met criteria for schizophrenia (n = 173) or schizoaffective disorder (n = 18) based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID; First et al., 1996). Additional selection criteria included age between 18 - 60 years, no substance use disorder in the past 6 months, no identifiable neurological disorder and IQ > 70 based on review of medical records, no history of loss of consciousness for more than 1 hour, and sufficient fluency in English to comprehend the informed consent form and study procedures. All participants had the capacity to give informed consent based on a quiz of main content, and they provided written informed consent after all procedures were fully explained in accordance with procedures approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the University of California, Los Angeles, (UCLA). One-hundred sixty-four patients were receiving atypical antipsychotic medications, 8 typical antipsychotic medications, 7 both types of medication, and 12 were not taking an antipsychotic. Demographic and clinical summary data are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information and symptom ratings

| Schizophrenia Patients (n = 191) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |

| Age | 46.6 | 9.8 |

| Education | 12.7 | 1.8 |

| Parental Education | 13.5 | 3.6 |

| Percent Male | 67.5% | |

| Duration of Illness (years) | 24.2 | 11.3 |

| Expanded BPRS* | 44.5 | 10.3 |

| Total Score | ||

| Factors (mean score per item) | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| Negative Symptoms | 2.2 | 0.9 |

| Positive Symptoms | ||

| SANS Global Scores | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Affective Flattening | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Alogia | 2.9 | 1.1 |

| Avolition | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| Anhedonia | ||

Measures

Brief descriptions of each measure are included below, and references are provided that contain more complete descriptions and, when available, psychometric properties of the measures when used with schizophrenia patients.

1. Visual Perception

Location masking

In the location masking task 37-39, the target consisted of a single square with a notch that could appear at the top, bottom or left side of the square. The target could appear at one of four different locations, arranged in a notional square, on the computer screen. The mask consisted of a pattern of squares that occupied every possible target location. The target was presented for 12.5 ms and the mask was presented for 25 ms. As in previous masking studies, we first used a psychophysical procedure to equate the participants on the target threshold so that each subject could identify an unmasked target at 84% accuracy. Both forward and backward masking was assessed. In forward masking the mask preceded the target, whereas in backward masking the mask followed the target. Six stimulus onset asynchronies (SOAs) were used in both forward and backward masking (12.5, 25.0, 37.5, 50.0, 62.5, 75 ms). Participants’ scores were averaged across SOAs separately for forward and backward masking.

4-dot masking

In the four-dot masking procedure four potential targets appeared in a notional square on the screen followed by a mask surrounding one of the potential targets 38, 40. The mask cues which target the participant was supposed to identify. The target array consisted of four squares with a notch missing from either the top, bottom or left side of the square, and the mask was four dots that surround, but do not touch, one of the potential targets. Target was presented for 25 ms and mask for 37.5 ms. Target stimuli were suprathreshold for all subjects, unlike the location masking condition which used an individual's threshold. Twelve trials were presented for each of eight SOAs (0, 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, 175 ms). In four-dot masking performance typically decreases with increasing SOAs, unlike the pattern for location masking. A summary score across the eight SOAs was used.

2. Ability

Social cognition

The Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity (PONS)

The PONS included the first 110 scenes of the full instrument 41, 42, and assesses social perception. Scenes of this videotape-based measure last 2 seconds and contain the facial expressions, voice intonations and/or bodily gestures of a Caucasian female. Each scene contains one, two, or three social cues. After watching each scene, the participant selects from two labels (e.g. saying a prayer; talking to a lost child) the one that best described the situation that was observed. As in prior studies that used the PONS in persons with schizophrenia, administration was modified to reduce demands on sustained attention and reading comprehension 8. Prior to each scene, the videotape was paused as the experimenter read the two possible labels aloud as the participant read the labels silently from a card. The number of correct responses is the dependent variable.

The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT, Part III)

The TASIT (Part III) is a measure of theory of mind (i.e., mentalizing) and consists of 16 videoed scenes, each lasting 15–60 seconds, depicting lies or sarcasm (8 of each) 43, 44. The lie scenes involved either white lies or sympathetic lies. A prologue/epilogue provided information to the viewer about the nature of the conversational exchange. Participants were asked to answer 4 types of forced-choice (yes/no) questions: The first asks the participant to think about what one character in the scene is doing to the other; the second asks what the character is trying to say to the other person; the third asks what the character is thinking; and the fourth asks what the character is feeling. The videotape is paused between each scene to allow the participant time to answer. The test provides an overall total score that was used in the current study.

Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test 2.0 (MSCEIT)

The MSCEIT is a self-report instrument that consists of 141 items and 8 ability subscales, which assess 4 components (branches) of emotion processing 45-47. As in previous studies with schizophrenia, the tester administered the MSCEIT test booklet individually to the participant 46. The first branch, “Identifying Emotions,” measures emotion perception in faces and pictures. The second branch, “Using Emotions,” examines how mood enhances thinking and reasoning and which emotions are associated with which sensations. The third branch, “Understanding Emotions,” measures the ability to comprehend emotional information, including blends and changes between and among emotions. The fourth branch, “Managing Emotions,” examines the regulation of emotions in oneself and in one's relationships with others by presenting vignettes of various situations, along with ways to cope with the emotions depicted in these vignettes. We used the MSCEIT total score.

Functional Capacity

UCSD Performance-based Skills Assessment (UPSA)

The UPSA is a performance-based simulation of daily activities and involves role-play tasks in five skill areas considered essential to functioning in the community 48. The areas include: General Organization, Finance, Social/Communications, Transportation, and Household Chores. Psychometrics of the UPSA used with schizophrenia are generally strong 22. The patients’ total UPSA summary score across the 5 areas was the dependent measure.

3. Beliefs / Motivation

Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS)

Participants completed the 15-item defeatist performance beliefs subscale from the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS) 49. The defeatist performance belief subscale has been the focus in previous schizophrenia research 33, and it consists of statements describing overgeneralized conclusions about one's ability to perform tasks (e.g., “If you cannot do something well, there is little point in doing it at all.”).

Negative symptoms

The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)

The SANS was used to evaluate negative symptoms during the preceding month 50. This interview-based rating scale contains anchored items that lead to global ratings of four negative symptoms: affective flattening, alogia, anhedonia/asociality, and avolition/apathy. SANS items and global ratings range from 0 (not at all) to 5 (severe). We separated negative symptoms into experiential (avolition and anhedonia) and expressive (affective flattening and alogia) components 7, 24.

4. Functional outcome

The Role Functioning Scale (RFS)

The RFS was used to assess functional status 51, 52. It is based on a semi-structured interview with the participant and includes subscales for work, independent living, family relations, and social functioning. The RFS ratings range from 1 (severely impaired functioning) to 7 (optimal functioning). Each RFS subscale provides anchored descriptions for all levels of functioning that capture both the quantity and quality of functioning in that domain.

Data analysis

SEM uses a combination of indicators (single variables) and latent variables (underlying factors) that can be estimated for constructs with three or more indicators. In the current data set, we had a sufficient number of indicators for perception, social cognition and functional outcome to estimate latent variables for these constructs. The remaining constructs were represented by a single indicator.

The relationship between the measured variables in the population was estimated using the sample covariance matrix, and the hypothesized latent structure was tested by fitting the measurement model linking the latent variables to their indicators. This confirmatory factor analysis supported the notion that social cognition and early visual perception are separable constructs. The latent variable “Early visual processing” was indexed with three indicators: forward masking, backward masking, and 4-dot masking. “Social cognition” was indexed with the total scores on the PONS, TASIT and MSCEIT. “Functional outcome” was a latent variable with four indicators: scores on independent living, work, family, and social functioning subscales of the RFS.

The hypothesized SEM models were estimated with the Structural Equation Package EQS 53. Of the fit indices available, we provide three commonly-reported indices that address different aspects of a well-fitting model to allow for a comprehensive evaluation of model fit 54. The Chi square statistic is a measure of absolute fit, i.e. it evaluates the difference between the sample covariance matrix and the covariance matrix implied by the fitted model, and it is very sensitive to sample size; the CFI is a measure of comparative fit, i.e. it evaluates how much improvement the fitted model offers over a model that assumes all measured variables are uncorrelated; and the RMSEA is a measure of absolute fit that is based on the non-centrality parameter of the Chi square statistic. The issue of missing data was addressed by first analyzing only complete cases, and repeating the analyses using a covariance matrix based on imputing missing data using the EM-algorithm 55. As the pattern of results was virtually identical, and pairwise percentage of missing data was below 10% in all cases, only the results with imputed data are reported.

Results

The summary statistics for each variable are shown in Table 2, and the bivariate intercorrelations among the measures are shown in Table 3. As expected, the intercorrelations among variables are generally higher within category (perceptual, ability, beliefs / negative symptoms) than between categories. The specific associations were then evaluated with SEM in a series of three models.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Forward Masking | 57.1% | 18.3 |

| Backward Masking | 43.8% | 16.6 |

| 4-Dot Masking | 55.3% | 15.1 |

| PONS | 78.6 | 7.1 |

| TASIT | 45.7 | 7.3 |

| MSCEIT | 82.3 | 13.3 |

| UPSA | 74.6 | 11.3 |

| Defeatist Beliefs | 51.9 | 18.1 |

| Expressive Negative Symptoms | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Experiential Negative Symptoms | 2.8 | 1.0 |

| Functional Outcome | 3.7 | 1.3 |

PONS: Profile of Non-verbal Sensitivity; TASIT: The Awareness of Social Inference Test; MSCEIT: Meyer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; UPSA: UCSD Performance Skills Assessment

Table 3.

Intercorrelations among measures included in the models

| Table 3 | Forward Masking |

Backward Masking |

4-Dot Masking |

Social Perception (PONS) |

Theory of Mind (TASIT) |

Emotion Processing (MSCEIT) |

Functional Capacity (UPSA) |

Defeatist Beliefs |

Expressive Negative Symptoms |

Experiential Negative Symptoms |

Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forward Masking | |||||||||||

| Backward Masking | .442** | ||||||||||

| 4-Dot Masking | .199* | .264** | |||||||||

| Social Perception (PONS) | .255** | .164* | .083 | ||||||||

| Theory of Mind (TASIT) | .233** | .200** | .281** | .526** | |||||||

| Emotion Processing (MSCEIT) | .087 | .113 | .225** | .466** | .488** | ||||||

| Functional Capacity (UPSA) | .089 | .093 | .242** | .460** | .479** | .477** | |||||

| Defeatist Beliefs | −.139 | −.122 | −.074 | −.257** | −.206** | −.363** | −.331** | ||||

| Expressive Negative Symptoms | .041 | −.018 | .050 | −.091 | .085 | .050 | −.069 | .166* | |||

| Experiential Negative Symptoms | −.166* | −.122 | .042 | −.130 | −.021 | −.083 | −.096 | .256** | .349** | ||

| Functional Outcome | .184* | .083 | .013 | .133 | .155* | .172* | .138 | −.287** | −.231** | −.703** |

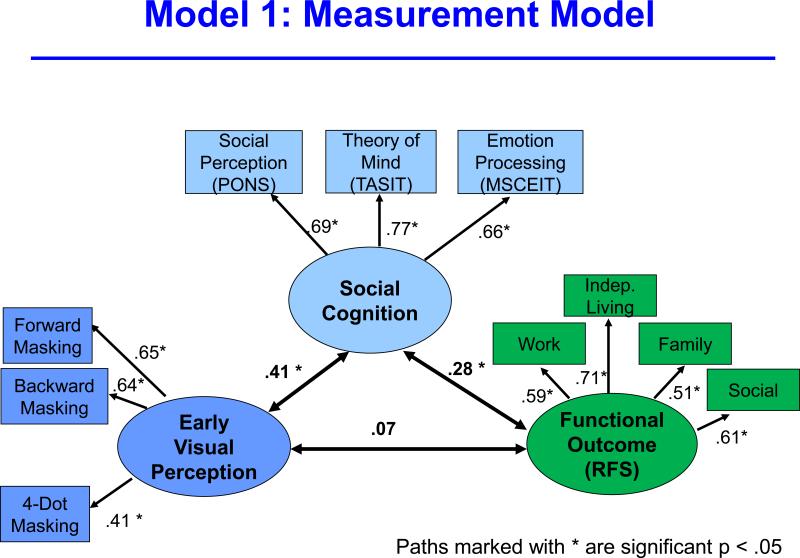

Measurement model

The first model examined the degree to which the latent variables for early visual perception, social cognition, and functional outcome loaded on their respective indicators (Figure 1). This first model is essentially a confirmatory factor analysis and model fit was extremely good (Chi square = 31.64, p = 0.48; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00), indicating that the latent variables and indicators were strongly associated. Based on this degree of fit, we reduced functional outcome to a single variable for subsequent models as a way to conserve free parameters and increase stability of the parameter estimates for the remaining models.

Figure 1.

The figure reflects a measurement model that shows the degree of fit between the three latent variables (early visual perception, social cognition, and functional outcome) and their respective indicators.

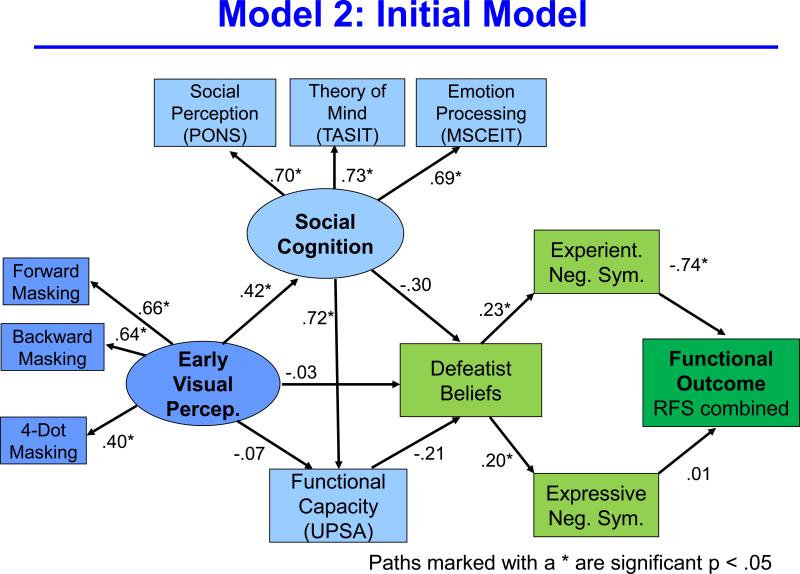

Initial model

We then added functional capacity, defeatist beliefs, and experiential and expressive negative symptoms to create a single path in the model (Figure 2). Model fit was good (Chi square = 74.90, p = 0.00; CFI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.08). Next, we made changes to this model based on conceptual and statistical considerations. For conceptual modifications, we dropped expressive negative symptoms because it was unrelated to functional outcome, which is the focus of this model. In terms of statistical considerations, we dropped functional capacity because of its very close association with social cognition. Due to this tight connection, the explained variance in defeatist beliefs was split between social cognition and functional capacity so that neither path was significant. Finally, modification indices from the EQS software were used to determine other paths that could be dropped to improve fit.

Figure 2.

This figure is a schematic of the initial, non-trimmed, structural model that includes all of the variables considered.

Final model

After the modifications mentioned above the resulting, more streamlined, model had good fit (Chi square = 39.41, p = 0.04; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.06). The model reflects a relatively linear sequence leading from perception to ability to beliefs / negative symptoms and to functional outcome. The strength of the model was supported by the significant standardized indirect effect of early visual processing through all other variables to functioning (.028; p<.05). In other words, we found a significant indirect effect through three intervening variables. This model explains 49% of the variance in RFS Total Score.

No changes were suggested through the modification indices that would turn the single pathway into a dual pathway (e.g., a separate path for motivation). The model was not improved by adding a direct link between social cognition and functional outcome that would create a pathway separate from negative symptoms. Also, the connection between ability and motivation (i.e. between social cognition and defeatist beliefs) was relatively high (- .44) and could not be dropped.

Compared to the initial model, the final model is more parsimonious (requiring fewer constructs and connections) and the fit indices are slightly higher. Because it is more parsimonious the model is also more stable: there are 18 free parameters and 191 subjects, which is more than 10 subjects per parameter. Based on these results, it can be concluded that a single pathway running from perception to ability to motivational variables to functioning provides good model fit, and additional paths do not improve the model.

Comment

We evaluated models of outcome in schizophrenia ranging from micro-level early visual perception to macro-level daily community functioning. We conclude that ability and motivational factors can be modeled effectively with a single, relatively streamlined, pathway. The a priori theories that generated this model stemmed from two separate literatures: one on connections between perceptual processing and social cognition, and one on connections between dysfunctional attitudes and negative symptoms. Results suggest that success in daily living involves both what patients can do, and also whether they are motivated to apply their abilities to the challenges of daily living.

The theoretical connection between perceptual processes and social cognition is based on a cascade model in which poor perceptual information contributes to inaccurate higher-level information 11, and it has received increasing support from the literature. Previous publications from our laboratory with an independent sample used a single measure of social cognition, social perception, that mediated the relationship between visual perception and functioning 7, 8. A previous paper 7 modeled visual perception to functional outcome and reported two mediating paths (one for social cognition and one for negative symptoms), but it did not include defeatist beliefs or any measure of dysfunctional attitudes. Hence it was lacking this key intervening step between ability and motivation. Also, other groups reported that problems in early auditory processing are associated with problems in emotion detection from voice prosody 11, 56, 57. Other studies found an early visual process (contour integration) is related to the higher-level social cognitive construct of theory of mind 58, 59.

Despite its strong theoretical grounding, the connection between defeatist beliefs and negative symptoms has received less empirical support so far. Studies from other groups have shown connections between defeatist beliefs and both negative symptoms and social functioning 29, 33, 35. Also, a previous study from our laboratory with a partially overlapping sample found defeatist beliefs were connected to a combined negative symptom score 34. An interpretive advantage of the current study is that we examined differential relationships between defeatist beliefs and expressive versus experiential negative symptoms (see also 29). Dysfunctional attitudes include more than defeatist beliefs, which was the focus in this study 32. Other beliefs, such as maladaptive beliefs about one's ability to communicate effectively, might be more closely linked to expressive negative symptoms. Understanding the determinants of experiential (as opposed to expressive) negative symptoms is particularly important given their strong relationship to functioning 7, 60.

Although functional capacity has been reported to be a determinant of outcome in other studies, it was not retrained in the final model in our study 10, 36. This decision was prompted by the very close association between our measure of functional capacity (UPSA) and the latent variable of social cognition. Due to this close association, the information provided by functional capacity was largely redundant with social cognition, and it split the covariance from ability to defeatist beliefs, leaving both pathways smaller and non-significant. In the context of this model, functional capacity acted more like an additional indicator for the social cognition latent variable. It would have been statistically possible to create a new latent variable of “ability” with social cognition and functional capacity, but our initial focus on social cognition guided the final model. The strong association between the UPSA and social cognition is consistent with similar findings from an independent sample from our laboratory 61. Evidence across laboratories and methods indicates that neurocognition, social cognition, and functional capacity have substantial intercorrelations (at least when using composite scores) and can be reasonably considered reflections of a general ability factor (e.g., 22, 62). Despite these strong associations, neurocognition and social cognition are modeled better as separate factors 63, 64.

As with all uses of SEM, this analysis is based on a priori theoretical models that guided the initial arrangement of variables. It is possible that other configurations of these variables would work equally well or better. We can only say that the observed data fit the proposed model (early perception to ability to beliefs to negative symptoms to functioning) rather well, and the integrated model in Figure 3 is a highly plausible sequence of steps based on that.

Figure 3.

This figure is the final, trimmed model after modifications. It shows a single path running through early visual perception, ability, beliefs / motivation, and functional outcome.

Beyond the constraints of the SEM method, this study had several limitations. As mentioned above, the study did not include measures of neurocognition (because data came from a project on perception and social cognition), but previously-reported intercorrelations among neurocognition, social cognition and the UPSA suggest they are all reasonable reflections of ability. Also, the study was cross-sectional. Hence, we do not know if the model would hold up if long term outcome had been used instead of concurrent outcome. Path analyses from a collaborative study that used a 12 month follow up and a different set of variables found similar results for cross-sectional and prospective analyses 52. On the other hand, we previously reported relationships between social cognition and outcome became stronger over time with first episode samples 65. In addition, the strong association between experiential negative symptoms and functional outcome might be partially explained by measurement overlap in these two areas 26. That is one reason for a recent effort to develop new scales that assess experiential negative symptoms as separately as possible from current community functioning 66. Our sample was predominantly male and relatively chronic, so its representativeness is limited. Also, because modification indices were used to refine the final model, replication with an independent sample is needed. Finally, the study only examined within-subject factors. Future models may want to include situational and contextual factors; e.g., family support, consistency of mental health services, and local economic conditions, among others.

It is mainly intuitive that perception is linked to ability, that defeatist beliefs are linked to negative symptoms, and that negative symptoms are linked to daily functioning. The result of putting the pieces together in an integrative model yields some less intuitive findings, particularly the transition from ability to motivation. However, these results match the theoretical framework outlined by Beck and colleagues who proposed that the repeated discouragement from having reduced abilities leads, over time, to dysfunctional attitudes such as defeatist beliefs. The model is essentially developmental; it assumes that the dysfunctional attitudes are built up over years of living with limited abilities. The current results are consistent with the predicted, but perhaps still surprising, finding that the connections from perception and ability to daily functioning work through motivational variables. This sequence of domains is also consistent with findings that cognitive therapy directed at dysfunctional attitudes can yield improvements in negative symptoms in schizophrenia patients 67.

The single pathway model that is supported in this study helps to provide a rationale for early perceptual and cognitive interventions, such as plasticity-based training 68. With a single pathway, it is theoretically possible (though not assured) that an intervention directed at early components (e.g. perception, cognition) could have beneficial effects on subsequent processing stages and functional outcome. With a dual pathway model, at least one intervention per path would be needed. The single pathway model also suggests that interventions for early components that occur early during the illness (e.g., prodromal or first-episode stages) could help prevent development of defeatist beliefs, thereby interrupting the detrimental consequences of the pathway.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Funding for this project came from NIH grants MH043292 and MH065707 (to MFG). After funding, NIH had no subsequent role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure:

Dr. Green reports having received consulting fees from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Cypress, Lundbeck, Shire, and Teva. He has received speaking fees from Otsuka and Sunovion. The rest of the authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A. Recovery from schizophrenia: a concept in search of research. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(6):735–742. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP, Ventura J, Zarate R, Mintz J. Neurocognitive correlates of recovery from schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(8):1165–1173. doi: 10.1017/s0033291705004575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenton WS, McGlashan TH. Antecedents, symptom progression, and long-term outcome of the deficit syndrome in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:351–356. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamsi S, Lau A, Lencz T, Burdick KE, DeRosse P, Brenner R, Lindenmayer JP, Malhotra AK. Cognitive and symptomatic predictors of functional disability in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;126(1-3):257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153(3):321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: Are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rassovsky Y, Horan WP, Lee J, Sergi MJ, Green MF. Pathways between early visual processing and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:487–497. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sergi MJ, Rassovsky Y, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF. Social perception as a mediator of the influence of early visual processing on functional status in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:448–454. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinants of real-world functional performance in schizophrenia subjects: Correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:418–425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowie CR, Depp C, McGrath JA, Wolyniec P, Mausbach BT, Thornquist MH, Luke J, Patterson TL, Harvey PD, Pulver AE. Prediction of real-world functional disability in chronic mental disorders: a comparison of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(9):1116–1124. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Javitt DC. When doors of perception close: bottom-up models of disrupted cognition in schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychololgy. 2009;5:249–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Light GA, Braff DL. Mismatch negativity deficits are associated with poor functioning in schizophrenia patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(2):127–136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wynn JK, Sugar C, Horan WP, Kern R, Green MF. Mismatch negativity, social cognition, and functioning in schizophrenia patients. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler PD, Zemon V, Schechter I, Saperstein AM, Hoptman MJ, Lim KO, Revheim N, Silipo G, Javitt DC. Early-stage visual processing and cortical amplification deficits in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(5):495–504. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rassovsky Y, Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Breitmeyer B, Mintz J. Modulation of attention during visual masking in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1533–1535. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey PD, Raykov T, Twamley EW, Vella L, Heaton RK, Patterson TL. Validating the Measurement of Real-World Functional Outcomes: Phase I Results of the VALERO Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10121723. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunda Z. Social cognition: Making sense of people. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiske ST, Taylor SE. Social cognition. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Book Company; New York, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green MF, Penn DL, Bentall R, Carpenter WT, Gaebel W, Gur RC, Kring AM, Park S, Silverstein SM, Heinssen R. Social cognition in schizophrenia: an NIMH workshop on definitions, assessment, and research opportunities. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2008;34:1211–1220. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt SJ, Mueller DR, Roder V. Social cognition as a mediator variable between neurocognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: empirical review and new results by structural equation modeling. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2011;37(Suppl 2):S41–54. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKibbin CL, Brekke JS, Sires D, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Direct assessment of functional abilities: Relevance to persons with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;72:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green MF, Schooler NR, Kern RS, Frese FJ, Granberry W, Harvey PD, Karson CN, Peters N, Stewart M, Seidman LJ, Sonnenberg J, Stone WS, Walling D, Stover E, Marder SR. Evaluation of functionally meaningful measures for clinical trials of cognition enhancement in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(4):400–407. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breier A, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, Pickar D. National Institutes of Mental Health longitudinal study of chronic schizophrenia: Prognosis and predictors of outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:239–246. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanchard JJ, Cohen AS. The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: implications for assessment. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:238–245. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saperstein AM, Fiszdon JM, Bell MD. Intrinsic motivation as a predictor of work outcome after vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2011;199(9):672–677. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318229d0eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanchard JJ, Kring AM, Horan WP, Gur R. Toward the next generation of negative symptom assessments: the collaboration to advance negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2011;37(2):291–299. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Rector NA. Cognitive approaches to schizophrenia: theory and therapy. Annual Review of Clinical Psycholology. 2005;1:577–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rector NA, Beck AT, Stolar N. The negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a cognitive perspective. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;50(5):247–257. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Couture SM, Blanchard JJ, Bennett ME. Negative expectancy appraisals and defeatist performance beliefs and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2011;189(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant PM, Beck AT. Asocial beliefs as predictors of asocial behavior in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2010;177(1-2):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granholm E, Ben-Zeev D, Link PC. Social disinterest attitudes and group cognitive-behavioral social skills training for functional disability in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2009;35(5):874–883. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck AT, Rector NA, Stolar N, Grant P. Schizophrenia: cognitive theory, research, and therapy. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant PM, Beck AT. Defeatist beliefs as a mediator of cognitive impairment, negative symptoms, and functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2009;35(4):798–806. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horan WP, Rassovsky Y, Kern RS, Lee J, Wynn JK, Green MF. Further support for the role of dysfunctional attitudes in models of real-world functioning in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2010;44(8):499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rector NA. Dysfunctional attitudes and symptom expression in schizophrenia: differential associations with paranoid delusions and negative symptoms. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 2004;18:163–173. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A, McClure MM, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Predicting schizophrenia patients’ real-world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measures. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63(5):505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Breitmeyer B, Tsuang J, Mintz J. Forward and backward visual masking in schizophrenia: influence of age. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:887–895. doi: 10.1017/s003329170200716x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Green MF, Wynn JK, Breitmeyer B, Mathis KI, Nuechterlein KH. Visual masking by object substitution in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1489–1496. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000214X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J, Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik K, Sugar C, Ventura J, Grechen-Doorly D, Kelly K, Green MF. Stability of visual masking performance in recent-onset schizophrenia: a 12-month follow up. Schzophrenia Research. 2008;103:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enns JT. Object substitution and its relation to other forms of visual masking. Vision Research. 2004;44:1321–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenthal R, Hall JA, DiMatteo MR, Rogers PL, Archer D. Sensitivity to nonverbal communication: The PONS test. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wynn JK, Sergi MJ, Dawson ME, Schell AM, Green MF. Sensorimotor gating, orienting and social perception in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;73:319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDonald S, Flanagan S, Rollins J. The Awareness of Social Inference Test. Thames Valley Test Company, Ltd.; Suffolk, UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kern RS, Green MF, Fiske AP, Kee KS, Lee J, Sergi MJ, Horan WP, Subotnik KL, Sugar CA, Nuechterlein KH. Theory of mind deficits for processing counterfactual information in persons with chronic schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:645–654. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR. Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) User's Manual. MHS Publishers; Toronto: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kee KS, Horan WP, Salovey P, Kern RS, Sergi MS, Fiske AP, Lee J, Subotnik KL, Nuechterlein KH, Sugar CA, Green MF. Emotional intelligence in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;107:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eack SM, Pogue-Geile MF, Greeno CG, Keshavan MS. Evidence of factorial variance of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test across schizophrenia and normative samples. Schizophrenia Research. 2009 Oct;114(1-3):105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD performance-based skills assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001;27(2):235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weissman A. Dysfunctional attitudes scale: a validation study. University of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, PA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andreasen NC. The scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS) The University of Iowa; Iowa City, IA: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 51.McPheeters HL. Statewide mental health outcome evaluation: a perspective of two southern states. Community Mental Health Journal. 1984;20(1):44–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00754103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brekke JS, Kay DD, Kee KS, Green MF. Biosocial pathways to functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;80:213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bentler PM. EQS: Structural equations program model. BMDP Statistical Software; Los Angeles, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jamshidian M, Bentler PM. ML estimation of mean and covariance structures with missing data using complete data routines. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1999;24:21–41. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leitman DI, Foxe JJ, Butler PD, Saperstein A, Revheim N, Javitt DC. Sensory contributions to impaired prosodic processing in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;58(1):56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leitman DI, Laukka P, Juslin PN, Saccente E, Butler P, Javitt DC. Getting the cue: sensory contributions to auditory emotion recognition impairments in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2010;36(3):545–556. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schenkel LS, Spaulding WD, Silverstein SM. Poor premorbid social functioning and theory of mind deficit in schizophrenia: evidence of reduced context processing? Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2005;39:499–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Uhlhaas PJ, Phillips WA, Schenkel LS, Silverstein SM. Theory of mind and perceptual context-processing in schizophrenia. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 2006;11(4):416–436. doi: 10.1080/13546800444000272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horan WP, Kring AM, Blanchard JJ. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: a review of assessment strategies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2006;32:259–273. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mancuso F, Horan WP, Kern RS, Green MF. Social cognition in psychosis: multidimensional structure, clinical correlates, and relationship with functional outcome. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;125(2-3):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Kern RS, Baade LE, Fenton WS, Gold JM, Keefe RSE, Mesholam-Gately R, Seidman LJ, Stover E, Marder SR. Functional co-primary measures for clinical trials in schizophrenia: Results from the MATRICS psychometric and standardization study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:221–228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sergi MJ, Rassovsky Y, Widmark C, Reist C, Erhart S, Braff DL, Marder SR, Green MF. Social cognition in schizophrenia: relationships with neurocognition and negative symptoms. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;90(1-3):316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bell M, Tsang HW, Greig TC, Bryson GJ. Neurocognition, social cognition, perceived social discomfort, and vocational outcomes in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009;35(4):738–747. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Horan WP, Green MF, de Groot M, Fiske AP, Hellemann G, Kee KS, Kern RS, Lee J, Sergi MJ, Subotnik KL, Sugar CA, Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH. Social cognition in schizophrenia, Part 2: 12 month prediction of outcome in first-episode patients. Schizophrenia bulletin. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr001. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blanchard JJ, Forbes C, Bennett M, Horan WP, Kring AM, Gur RE. Initial development and preliminary validation of a new negative symptom measure: The clinical assessment inventory for negative symptoms. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;124:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grant PM, Huh GA, Perivoliotis D, Stolar NM, Beck AT. Randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of cognitive therapy for low-functioning patients with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(2):121–127. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fisher M, Holland C, Merzenich MM, Vinogradov S. Using neuroplasticity-based auditory training to improve verbal memory in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(7):805–811. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08050757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ventura J, Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Liberman RP, Green MF, Shaner A. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) expanded version: scales, anchor points, and administration manual. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1993;3:227–243. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, Liberman RP, Mintz J. Consistency of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale factor structure across a broad spectrum of schizophrenia patients. Psychopathology. 2008;41(2):77–84. doi: 10.1159/000111551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]