Abstract

Coupled ligand binding and conformational change plays a central role in biological regulation. Ligands often regulate protein function by modulating conformational dynamics, yet the order in which binding and conformational change occurs are often hotly debated. Here we show that the “conformational selection versus induced fit” on which this debate is based is a false dichotomy because the mechanism depends on ligand concentration. Using the binding of pyrophosphate (PPi) to B. subtilis RNase P protein as a model, we show that coupled reactions are best understood as a change in flux between competing pathways with distinct orders of binding and conformational change. The degree of partitioning through each pathway depends strongly on PPi concentration, with ligand binding redistributing the conformational ensemble toward the folded state by both increasing folding rates and decreasing unfolding rates. These results indicate that ligand binding induces marked and varied changes in protein conformational dynamics, and that the order of binding and conformational change is ligand concentration dependent.

Many biological systems couple protein conformational change to ligand binding. This coupling underlies all allosteric regulation. A mechanistic description, including the order in which binding and conformational change occur, is required for understanding the molecular basis of biological regulation and for rational drug design. Discussion of conformational coupling mechanism has focused on “conformational selection” and “induced fit” mechanisms, which represent limiting extremes of the order of events1–3. In conformational selection, ligand binds directly to the poorly populated high-affinity conformational ensemble. In induced fit, ligand binds to the highly populated low-affinity ensemble followed by a transition to the high-affinity ensemble. These ensembles are distinguishable by the highly cooperative kinetic barriers that separate them. Numerous experimental studies have sought to determine which of these mechanisms predominates in various systems. Previous experimental studies have highlighted the necessity of performing kinetic experiments to distinguish between the mechanisms4,5. One such study treated conformational selection and induced fit mechanisms as mutually exclusive for a given protein-ligand pair and did not consider the possibility that a change in ligand concentration might cause a change in mechanism4. Despite observation of combined conformational selection and induced fit mechanisms in silico6–8, kinetic experiments have failed to yield mechanisms that describe the partitioning between induced fit and conformational selection. Here we use thermodynamic, structural, and kinetic data to obtain a detailed kinetic description of coupled folding and binding in Bacillus subtilis RNase P protein using the ligand pyrophosphate (PPi). We perform a flux-based analysis9 of kinetic data obtained over a wide range of ligand concentrations and show that flux is kinetically partitioned between alternate reaction pathways described by both conformational selection and induced fit. The partitioning depends on ligand concentration. We also report binding affinities to the low- and high-affinity protein conformations and show that ligand binding redistributes the conformational ensembles by increasing folding rates and decreasing unfolding rates.

Bacterial RNase P is a ribonucleoprotein complex that cleaves the 5’-leader sequence from pre-tRNA10–12. The P RNA subunit is catalytically active in vitro13, while the protein subunit enhances substrate specificity14,15. The B. subtilis protein subunit has three conformational sub-ensembles16 and two high affinity ligand binding sites17. The unfolded state predominates when the protein is not bound to anions. Folding of RNase P protein in the absence of ligand can be induced with osmolytes such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). Binding of small anions shifts the conformational equilibrium to populate the folded state. This ligand-induced conformational change, depicted in Figure 1, serves as a good model for studying how binding is coupled to conformational change in proteins.

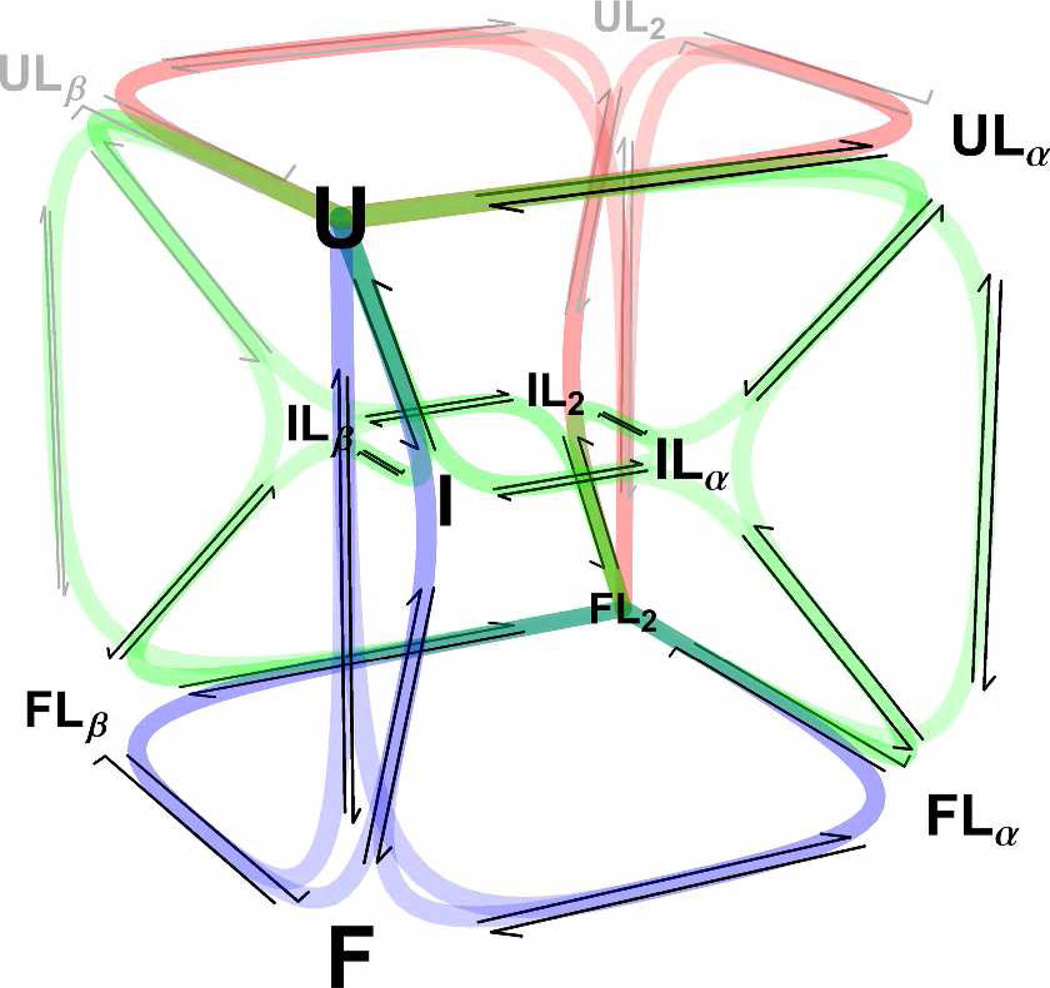

Figure 1.

P−Pro coupled folding and binding scheme. P−Pro exhibits three-state folding with unfolded (U), partially folded intermediate (I), and folded (F) states. Folding is strongly coupled to the binding of two pyrophosphate ligands (L). Pyrophosphate may be bound at the α-site (Lα), β-site (Lβ), or both sites (L2) in any state. Unoccupied binding sites in U and I are reflected as undetectably weak affinities in the fits of the data. Species that remain unpopulated in 0 – 1 mM PPi —as revealed by fits of the data—and their associated transitions are indicated in gray. Conformational selection pathways are shown in blue, induced fit pathways in red, and mixed pathways in green.

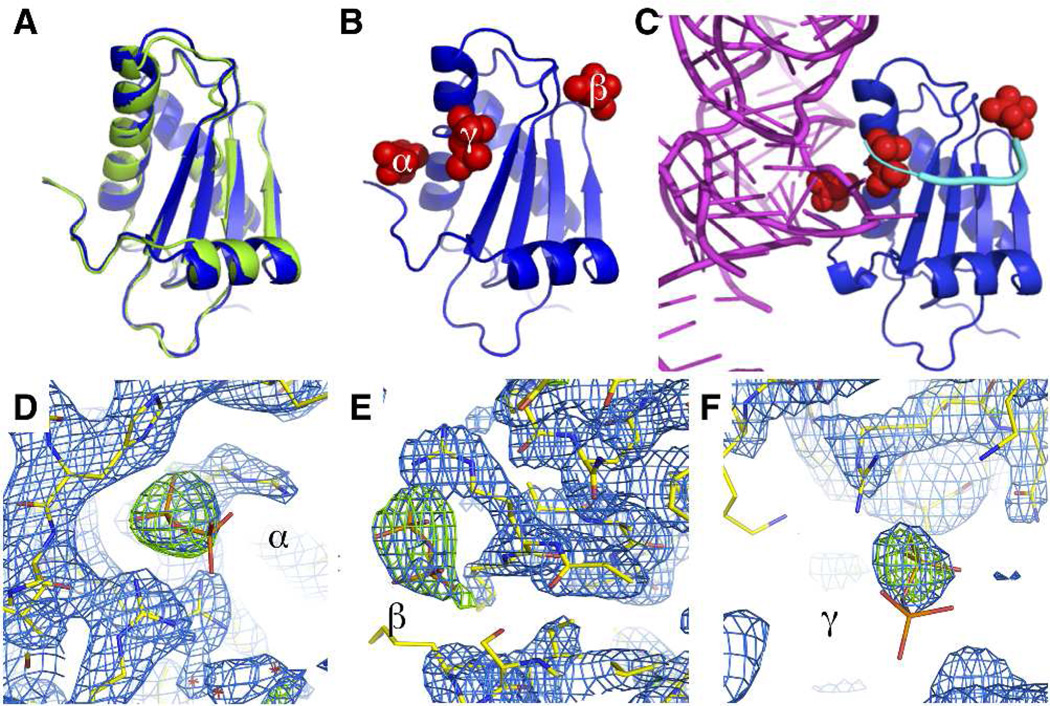

In the present work, we have substituted two prolines with alanines to simplify the mechanism and have shown that the substitutions do not alter P protein structure or function. The F107W/P39A/P90A variant (referred to hereafter as P−Pro) was structurally characterized by X-ray crystallography. The structure of P−Pro is nearly superimposable with the structure of wildtype P protein18 (RMSD = 0.53 Å) (Figure 2A). PPi molecules occupy each of the two previously identified binding sites (Figure 2B)19. Electron density for a third PPi was observed proximal to Arg60. This binding site, referred to as the γ site, binds PPi too weakly to contribute significantly to the coupled folding and binding mechanisms at the concentrations used in our stopped-flow experiments. In agreement with the binding data, electron density maps of the three PPi sites shows clearly defined density for PPi of sites α and β while the electron density for the γ site only shows clear density for the bound phosphate with weak density surrounding the second unbound phosphate (Figure 2D–F). Furthermore, superposition of the P−Pro structure with the protein subunit of the T. maritima RNase P holoenzyme structure indicates that PPi binds to P−Pro at sites that bind P RNA or the 5’ leader of precursor tRNA (Figure 2C). Integrity of the P−Pro and the previously studied F107W variants was also assessed by their ability to form active RNase P holoenzyme. RNase P containing either variant was able to cleave fluorescently labeled pre-tRNAAsp (Figure S1). Based on the minimal structural perturbations and retention of activity, we deemed the P−Pro reasonable to use for determining the mechanism of coupled binding and folding.

Figure 2.

Crystal structure of P−Pro. (A) Alignment of crystal structures of wildtype (green, PDB 1A6F) and P−Pro (blue) B. subtilis RNase P protein subunit. Structures are aligned on the Cα backbone atoms of residues 2–114. (B) Crystal structure of P−Pro bound to pyrophosphate (red). The binding sites are designated α, β, and γ and have been assigned to specific species in the binding/folding mechanism as described in the text. (C) The structure of P−Pro (blue) in complex with pyrophosphate (red) was inserted into the crystal structure of Thermatoga maritima RNase P (PDB 3OKB)20 in place of the T. maritima protein subunit. P−Pro was oriented by alignment with the Cα backbone of the T. maritima protein. The T. maritima RNase P RNA is shown in magenta and RNA 5’ leader sequence is shown in cyan. (D, E, F) Averaged kick omit maps of the three pyrophosphate binding sites. The 2Fobs – Fcalc map is shown in blue and is contoured at 1σ. The Fobs – Fcalc map is shown in green and is contoured at 3σ.

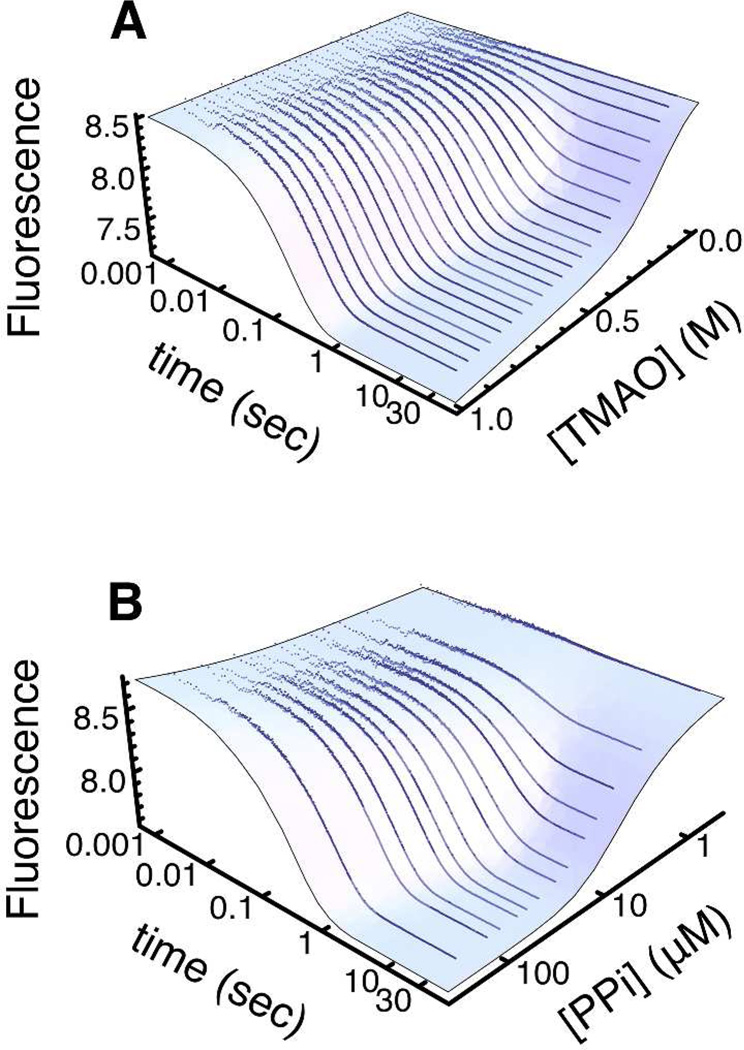

We used stopped-flow fluorescence to monitor folding of P−Pro upon mixing with TMAO or PPi (Figures 3 and S2). Rather than fit to a series of exponentials, we used a Bayesian estimation method (Markov Chain Monte Carlo followed by sequential Monte Carlo) to globally fit all kinetic transients for both TMAO- and PPi-induced folding to a model containing thermodynamic, kinetic, and spectroscopic parameters (Tables S2–S5) for the kinetic scheme depicted in Figure 1. To implement the model, we used a series of ordinary differential equations (see Supporting Information) to describe the time-dependent free ligand concentration and populations of twelve microscopic protein species depicted in Figure 1. The time-dependent populations were then used to express the total fluorescence signal as a sum of population-weighted signals. This approach allowed us to analyze data collected under non-pseudo-first order conditions, in which total ligand concentrations ranged from 0.16 to 66 times the protein concentration and spanned the apparent KD.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of TMAO-induced (A) and pyrophosphate-induced (B) folding of P−Pro were monitored by stopped-flow fluorescence. Data points are the average of data points from three traces. The blue surfaces are the global best-fit of the data to the coupled folding and binding model.

The α site in the folded state, implicated in the NMR PRE experiments and our stopped-flow experiments as being the highest affinity site, contains residues identified as the unfolded state α site. In the NMR PRE and stopped-flow experiments, the next highest affinity site is the β site. The γ site has the lowest affinity (confirmed by ITC) of the sites observed by NMR PRE experiments. Surprisingly, all three conformational ensembles – unfolded (U), partially folded (I), and folded (F) – have detectable affinity for PPi, based on the fits of stopped-flow data (Table S5). The measured affinities of U and I for PPi are nearly impossible to obtain from equilibrium experiments because the equilibrium populations of PPi-bound U and I do not exceed 1%. However, in our kinetic experiments we detected affinity (2.6 mM) in U for a single PPi at a site mechanistically linked to the highest affinity site in F. A peptide mimic of the fifteen N-terminal residues that we believe contain the U binding site of P−Pro binds PPi with a similar affinity as U (Figure S3A–S3C and Table S6). We also detected affinity for the α and β binding sites in both I (120 µM and 460 µM) and F (0.76 µM and 2.3 µM). Affinity for the γ binding site (40 µM) was observed by ITC titration of 200 µM P−Pro with PPi (Figure S3D). However, the affinity is too low for the site to contribute significantly to the coupled folding and binding mechanism at the concentrations used in our stopped-flow experiments. The affinities of U and I are particularly insightful for understanding how PPi binding redistributes the ensemble towards F. From a kinetic standpoint, redistribution of the ensemble may result from increased folding rate constants, decreased unfolding rate constants, or both. Binding to U and I are prerequisites for increased folding rate constants. By comparing the conformational rate constants for free and PPi-bound P−Pro, we show that PPi redistributes the P−Pro ensemble by changing both folding and unfolding rate constants.

The kinetic parameters of the best-fit model reveal a variety of effects of PPi binding on the kinetics of P−Pro conformational changes. Estimates of rate constants for the conformational transitions shown in gray in Figure 1 were not obtained because U lacks a detectable β site, such that these transitions do not contribute to the coupled folding and binding mechanism. We analyzed rate constants for the remaining transitions shown in black (Table S4), and concluded that the folding and unfolding rate constants for P−Pro depend on the number of PPi bound to P−Pro (zero, one, or two) and the site at which the PPi is bound (α, or β, or both). In general, binding of PPi to P−Pro increases folding rate constants and decreases unfolding rate constants, shifting the conformational equilibrium toward the more folded states. The relative contribution of folding and unfolding rate constants to the shift in equilibrium varies between the different conformational transitions. With PPi bound at the α site, the equilibrium constant for the U to I transition (KUI) increases 21-fold but only 7% of the increase is due to a larger folding rate constant. In contrast, with PPi bound at the α site the equilibrium constant for the U to F transition (KUF) increases 3400-fold and approximately 95% of the increase is due to a larger folding rate constant. The degree to which PPi binding changes the folding and unfolding rate constants can be interpreted in terms of the affinities of the transition states relative to U, I, and F. The U to I transition state has an α site that is similar to that of U, while the U to F transition state’s α site is similar to that of F. These transition states have no detectable β site. Binding of PPi perturbs the energies of the ground states and transition states of the conformational reactions, thereby altering the dynamics of P−Pro. The affinities of the transition states are different for each conformational reaction in the P−Pro mechanism, such that binding of PPi redistributes the ensemble by increasing the folding rate constants and decreasing the unfolding rate constants differently for each conformational reaction.

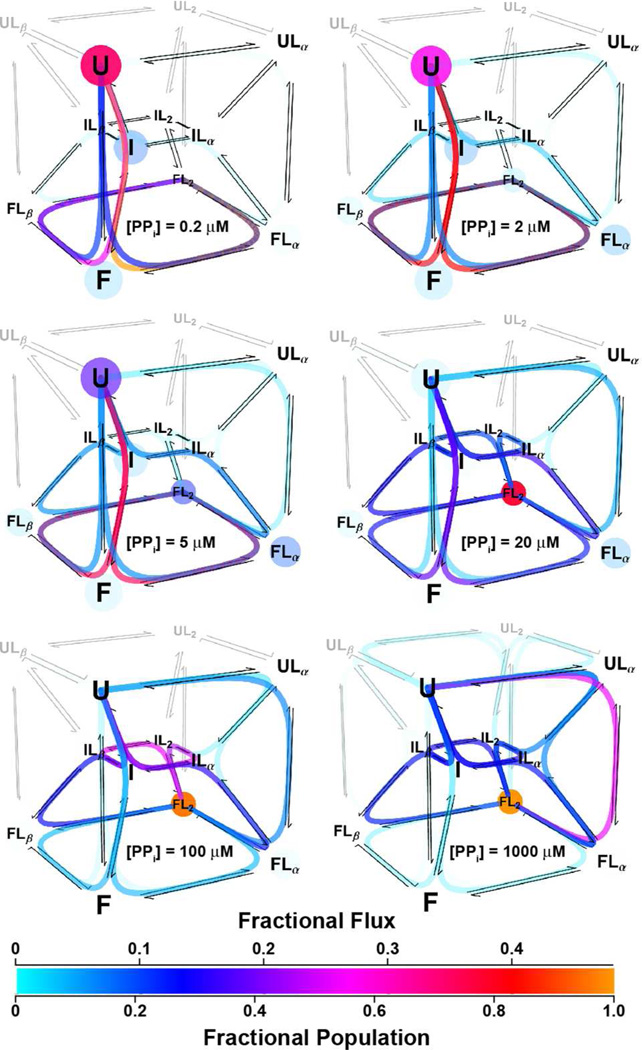

The mechanism of coupled folding and binding in P−Pro shows that both the population distribution of members within the ensemble and the preferred pathways by which these ensemble members interconvert depend on PPi concentration. To describe the interconversion of P−Pro ensemble members we calculated the equilibrium flux9 through the 18 reaction pathways by which U and FL2 exchange. Four of the pathways follow the conformational selection mechanism and four follow the induced fit mechanism. The remaining ten pathways follow mixed mechanisms in which folding and binding alternate.

The total flux through all pathways between U and FL2 reaches a maximum of ~30 % s−1 near the apparent KD for PPi (~2 µM) when half of the protein molecules are folded (Figure S4), then decreases substantially as the concentration of ligand increases or decreases from the apparent KD. The flux is kinetically partitioned between the 18 pathways. Each pathway’s fractional contribution to the total flux depends on PPi concentration (Figure 4). At PPi concentrations at or below the apparent KD of 2 µM, approximately 90% of the total flux is through the four conformational selection pathways. As PPi concentration increases, the contribution of the conformational selection pathways to the total flux decreases, and the contribution of the mixed mechanism pathways increases. In the presence of 20 µM PPi, 10-fold above the apparent KD, 70% of the total flux is through seven of the mixed mechanism pathways. Approximately 12% of the total flux is through pathways in which U protein binds ligand before folding, and 58% of the flux is through pathways in which I binds ligand before folding. Most of the remaining 30% of the total flux is through the conformational selection pathways that dominate at lower ligand concentrations. As ligand concentration increases, the fractional flux through pathways in which U binds ligand before folding continues to increase. Since U does not have a β site, the four fully induced-fit pathways in which U binds two molecules of PPi before folding do not contribute significantly to the coupled folding and binding mechanism.

Figure 4.

The mechanism of coupled folding and binding is concentration dependent. The mechanism of interconversion between U and FL2 was assessed by calculating the fractional flux through each of 18 pathways. Species populations (spheres) and fractional fluxes (path lines) were calculated for 2.5 µM protein and the indicated pyrophosphate concentrations using parameter values derived from the global best-fit of TMAO- and PPi-induced folding stopped-flow data. The populations and fluxes were calculated using. A movie version of this figure is available as a .qt file.

The kinetic partitioning observed in P−Pro coupled folding and binding is not adequately described by the “conformational selection versus induced fit” dichotomy often used to describe coupled conformational change and binding reactions. In this false dichotomy the overall reaction is classified into only one of the two limiting mechanisms. An important feature of the P−Pro coupled folding and binding mechanism, and we would suggest most others, is that flux through the multiple distinct pathways is kinetically partitioned. The kinetic partitioning is strongly dependent on the rate constants for conformational change, the ligand binding affinities of the conformational states, and the free ligand concentration. Based on our assessment of the P−Pro mechanism and flux calculations we can draw general conclusions about dependencies of the partitioning. Fast folding kinetics in the unliganded, low affinity sub-ensemble, and low ligand concentration favor partitioning into conformational selection pathways. Slow folding kinetics in the unliganded protein and high affinity in the unfolded state favor partitioning into induced fit pathways. When the unfolded state is capable of binding ligand at a particular site, increasing ligand concentrations favors partitioning through pathways that begin with ligand bound to U at that site.

For many proteins coupled binding and conformational change may be kinetically partitioned between competing pathways, however, previous methodology and interpretation limited to the false dichotomy has precluded such observations. While the precise biological utility of a given coupled binding and conformational change mechanism is currently unknown, it is certain that biology and mechanism can only be correlated if the mechanism is properly determined. Kinetic experiments should be done over a wide range of ligand concentrations and used to determine rate constants for elementary steps. This analysis is applicable to simple systems but also more complex systems, as long the data captures information about each of the elementary steps. Our study of P−Pro suggests two possible biological implications of a concentration-dependent mechanism. First, concentration-dependent partitioning gives rise to a potentially regulatory kinetic effect. The folding rate constants increase when ligand is bound, making induced fit faster than conformational selection. At low ligand concentrations where conformational selection dominates, folding is a slow step. At higher concentrations where induced fit dominates, proteins bypass this slow step. Second, the flux is kinetically partitioned between pathways with conformationally distinct intermediates. In some cases, these intermediates might participate in different biological processes (eg., binding different partners), and varying ligand concentration can be used to favor a particular pathway and a process associated with the intermediate in that pathway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Homme Hellinga for insightful discussion. The data presented in this manuscript are tabulated in the main paper and supporting information. We thank the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team 22-BM beamline at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory and their support staff; use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, and the Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract W-31-109-Eng-38.

Funding Sources

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1GM061367, RO1GM081666, R01GM40602, and R01GM090201, National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Grant 1106401 and National Science Foundation Training Grant DMS-1045153-003.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information.

Materials and methods, supporting figures and tables, equations, and movie. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kiefhaber T, Bachmann A, Jensen KS. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2012;22:21. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:54. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boehr DD, Nussinov R, Wright PE. Nature chemical biology. 2009;5:789. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogt AD, Di Cera E. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5894. doi: 10.1021/bi3006913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim E, Lee S, Jeon A, Choi JM, Lee H-S, Hohng S, Kim H-S. Nature chemical biology. 2013;9:313. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kondo HX, Okimoto N, Morimoto G, Taiji M. The journal of physical chemistry. B. 2011;115:7629. doi: 10.1021/jp111902t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva D-A, Bowman GR, Sosa-Peinado A, Huang X. PLoS computational biology. 2011;7:e1002054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bucher D, Grant BJ, McCammon JA. Biochemistry. 2011;50:10530. doi: 10.1021/bi201481a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammes GG, Chang YC, Oas TG. PNAS. 2009;106:13737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907195106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson HD, Altman S, Smith JD. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:5243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank DN, Pace NR. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurz JC, Fierke CA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;4:553. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerrier-Takada C, Gardiner K, Marsh T, Pace N, Altman S. Cell. 1983;35:849. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niranjanakumari S, Stams T, Crary SM, Christianson DW, Fierke CA. PNAS. 1998;95:15212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurz JC, Niranjanakumari S, Fierke CA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2393. doi: 10.1021/bi972530m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang YC, Oas TG. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5086. doi: 10.1021/bi100222h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henkels CH, Kurz JC, Fierke CA, Oas TG. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2777. doi: 10.1021/bi002078y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stams T, Niranjanakumari S, Fierke CA, Christianson DW. Science. 1998;280:752. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang YC, Franch WR, Oas TG. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9428. doi: 10.1021/bi100287y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reiter NJ, Osterman A, Torres-Larios A, Swinger KK, Pan T, Mondragon A. Nature. 2010;468:784. doi: 10.1038/nature09516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.