Abstract

Studies examining friendships among Mexican-American adolescents have largely focused on their potentially negative influence. The current study examined the extent to which deviant and achievement-oriented friend affiliations are associated with Mexican-American adolescents’ school adjustment and also tested whether support from friends and parents moderates these associations. High school students (N = 412; 49 % male) completed questionnaires and daily diaries; primary caregivers also completed a questionnaire. Although results revealed few direct associations between friend affiliations and school adjustment, several moderations emerged. In general, the influence of friends’ affiliation was strongest when support from friends was high and parental support was low. The findings suggest that only examining links between friend affiliations and school outcomes does not fully capture how friends promote or hinder school adjustment.

Keywords: Friend affiliations, Friend support, Parental support, Mexican-American youth, School adjustment

Introduction

It is well documented that Latino students are at greater risk for doing poorly in school compared to students from other ethnic groups (Gándara and Contreras 2009; National Center for Education Statistics 2013). In particular, Mexican-American students are disproportionately at-risk for school failure. For example, since 1980, Mexican-Americans have had the lowest rates of high school completion, compared to Whites, Blacks, Asian and Pacific-Islander groups, and also youth from other Latino groups (e.g., Puerto Ricans; U.S. Census Bureau 2010). Furthermore, Mexican-American students are less engaged in informal academic activities such as homework and extracurricular activities, compared to non-Latino White students (Ream and Rumberger 2008). Mexican-American youth face significant barriers to scholastic success in the US, and as the largest Latino group in the US, their representation in public school systems is rapidly growing (Pew Hispanic Research Center 2011). Thus, factors associated with school adjustment among Mexican-American youth is an important topic of research.

To date, most studies examining why Mexican-American students do poorly in school have focused on neighborhood, home, and family characteristics such as limited English proficiency (Rumberger and Larson 1998) and parenting practices (Dumka et al. 2009). For example, youth growing up in disadvantaged families may have restricted access to resources and social capital to support education, particularly among immigrant families in which parents have not attended US schools (Cooper and Crosnoe 2007; Turney and Kao 2009). Moreover, Mexican-American youth tend to have fewer educational role models in their families and communities and greater exposure to deviant peer influences in their schools and neighborhoods (e.g., Germán et al. 2009). Thus, for many Mexican-American students, managing these educational barriers within the neighborhood, home and family may make it particularly difficult to excel in school.

Although youth spend much of their school time with peers who help shape emotional, social and cognitive development (Bukowski and Mesa 2007), few studies have examined how perceived affiliations and relationships with friends may play a role in the school adjustment of Mexican-American students. The few studies that have examined the influence of friends among Latino youth have largely focused on their potentially negative influence. The current study addresses this gap in the research by examining the positive and negative influences of friendships on Mexican-American adolescents’ school adjustment. Specifically, we examine the extent to which adolescents’ perceived deviant and achievement-oriented friend affiliations are associated with their educational aspirations, attendance problems and academic problems.

The current study is informed by ecological theory (Bronfenbenner 1979), which has been widely used to inform research on school outcomes (Richman et al. 2004), including research with Latino students (Woolley et al. 2009). Ecological theory posits that social interactions are a part of a larger ecological system. The adolescent’s microsystem is characterized as consisting of interpersonal relationships with people whom they have a lasting relationship, such as parents and friends (Muuss 2006). Moreover, ecological theory expects that the influence of specific relationships may interact and become more or less influential across time. Stemming from this framework, we highlight the role of friends, but also examine how multiple social environments may influence school outcomes by testing whether support from parents and friends attenuate or amplify potential links between friend affiliations and school adjustment. That is, we test whether the nature of peer influence (i.e., achievement-oriented and deviant) depends upon the quality of peer and parent relationships.

The Role of Friend Affiliations

The important role that friends play in the everyday lives of adolescents and their school adjustment has been highlighted by past research (e.g., Berndt and Keefe 1995; Kingery et al. 2011). Berndt (1999) described how having friends with certain characteristics can influence students’ adjustment in school. For example, through observational learning, students can be negatively influenced by friends who engage in disruptive behaviors at school. Among research with Latino adolescents, and with Mexican-American adolescents in particular, studies have almost exclusively examined the influence of deviant friend affiliations and the strong links with problem behaviors (e.g., Barrera et al. 2004; Eamon and Mulder 2005; Frauenglass et al. 1997). This research indicates that not only are affiliations with deviant friends associated with problem behaviors such as substance use (e.g., Germán et al. 2009), but deviant friends may also negatively influence school outcomes. Woolley and colleagues found that among Latino middle school students, friends’ negative school behaviors (e.g., cutting class, getting in trouble) predicted their own school behaviors (Woolley et al. 2009). Mexican-American tenth graders who report having more friends drop out of high school are more likely to drop out of high school before twelfth grade themselves (Ream and Rumberger 2008).

Although more attention has been paid to the negative influence of Mexican-Americans’ friends, past research with other ethnic groups has shown that adolescents’ friends can also have positive influences. Based on social capital theory, involvement with positive peer groups, such as affiliations with achievement-oriented friends, may serve as an asset because the relationship ties provide access to certain resources (e.g., information, modeling of prosocial behavior) that promote positive school adjustment (Crosnoe et al. 2003). Only a handful of studies have empirically tested whether reports of affiliating with more academically inclined friends promotes positive school adjustment among Mexican-American adolescents. In the study previously mentioned, Ream and Rumberger (2008) demonstrated that among adolescents (including Mexican-Americans), having friends who value education reduced the likelihood of dropout. Additionally, Azmitia and Cooper (2001) found that White and Latino (predominately Mexican-American) adolescents’ perceptions of their friends as encouraging of school achievement was significantly associated with math and English grades.

The current study examines negative and positive aspects of friends by asking Mexican-American adolescents’ about their affiliations with deviant and achievement-oriented friends. By including both types of friend affiliations, results will provide a broader understanding of how friends are linked to school adjustment by focusing on their potential to serve as both antisocial and prosocial influences. The current study also goes beyond simply examining the types of friends with whom adolescents affiliate by examining how types of friends may interact with the perceived support and companionship that adolescents feel they receive from these friends.

Does the Influence of Friend Affiliation Depend on Levels of Support from Friends?

Through childhood and adolescence, there is an increased reliance on friends as a source of support (Furman and Buhrmester 1992). However, research has been mixed as to how perceived support from friends is associated with school adjustment outcomes. On the one hand, some studies suggest that Latino adolescents who have high support from friends will also have positive school adjustment. Garcia-Reid et al. for example, found that among low-income middle school Latino students, friends’ support (i.e., level of trust and closeness that adolescents feel toward their friends) was positively associated with engagement in school (Garcia-Reid et al. 2005; Garcia-Reid 2007). Alternatively, some studies suggest that friends’ support is unrelated to school adjustment among Latino adolescents. In a study of academic achievement among immigrant adolescents (23 % of the sample was Latino and composed of mostly Mexican-origin teens), Fuligni (1997) found bivariate associations between peer support for achievement (e.g., how often friends encourage each other to do well in school) and their own academic achievement. However, support from peers did not independently predict adolescent’s academic achievement above and beyond other factors in the model such as students’ own attitudes toward school. Fuligni notes that the effects of the peer group were likely channeled through the more proximal factors of the students’ own attitudes and behaviors. Similarly, a study of Latino students from predominately Mexican-American backgrounds across sixth to twelfth grade, found no association between friends’ support and academic outcomes (DeGarmo and Martinez 2006).

One explanation for the inconsistent friends’ support findings is that the type of friends with whom adolescents are affiliating interacts with the influence of friends’ support in meaningful ways. For example, for an adolescent who affiliates with a greater proportion of deviant peers, high levels of support may serve as a reinforcement of their own negative behaviors and amplify the negative influence of deviant friends. Thus, within the context of affiliating with deviant friends, it may not be beneficial to perceive high levels of support. Conversely, for an adolescent who affiliates with achievement-oriented peers, high levels of support may be especially beneficial if this support amplifies their friends’ positive influence. Indeed, researchers have speculated that adolescents may be more likely to be influenced by the behaviors (both positive and negative) of the friends with whom they have the best relationships (Chester et al. 2007). To date, research examining friends’ support and research on friend affiliations or type of friends has largely remained disconnected (see Berndt 1999 and Agnew 1991 for exceptions). The current study directly examines how the influence of friend affiliations varies, as a function of perceived support from friends among Mexican-American adolescents.

The Interactive Influence of Parents and Peers

Ecological theory underscores the importance of examining how multiple social environments impact youth development. Bronfenbenner’s (1979) model outlines specific key microsystems that impact youth development, including the family and peer group. In a review of research on family-peer linkages in adolescence, Brown and Bakken (2011) provide evidence to dismiss the overemphasis in research that parents and peers are competing influences in the lives of youth and highlight the ways in which parenting and peer relationships interact to affect adjustment. Given the important role that both friendships and parent–child relationships play in the lives of adolescents, these relationships may interact in significant ways to influence adjustment (Rubin et al. 2004). Given that families and parents play a particularly important role for Mexican-American adolescents (e.g., Telzer and Fuligni 2009), it is important to examine how perceived parental support may reduce or strengthen the influence of friend affiliations on school adjustment. Although no studies among Latinos have examined this parent-peer interactive hypothesis in relation to school adjustment, studies focusing on externalizing problems illustrate how parent–child relationships can moderate friend associations.

Germán et al. (2009) showed that the familism values of adolescents and their parents (e.g., familial obligations, perceived closeness) protected Mexican-American adolescents from the negative influence of deviant friend affiliations on externalizing problems. The authors noted that these results are consistent with the theory of social control, which asserts that one way of preventing delinquent behaviors may be via adolescents holding bonds to conventional institutions such as the family (Hirschi 1969). In a study of African–American youth from single-parent homes, Chester et al. (2007) demonstrated that positive parenting (mothers’ reports of monitoring, warmth and support) moderated the association between friendship quality and externalizing problems. Compared to when positive parenting was high, at low levels of positive parenting, friend quality was more strongly associated with externalizing problems, such that youth reported more externalizing symptoms. Whereas Germán and colleagues showed that family relationships may serve to protect adolescents, the results of this study highlight that poor relationships with parents may exacerbate externalizing problems, specifically in the context of high-quality peer relationships. Youth may be especially likely to turn to their friends when relationships with parents are weak, but if friends’ support is provided for rule-breaking behavior or involves partaking in deviant behaviors, friends’ support may not be beneficial (Chester et al. 2007). Overall, these results highlight that parents and friends play an important role in problem behaviors, and furthermore, they suggest that it is important to consider the type of friends with whom adolescents are affiliating. The current study specifically tests whether parental support weakens or strengthens associations between both deviant friend and achievement-oriented friend affiliations with school adjustment.

Aims of the Current Study

Three main aims guide the current study. First, at a descriptive level, this study tested whether gender, grade, or generational status are associated with differences in Mexican-American adolescents’ affiliations with deviant friends, affiliations with achievement-oriented friends, perceived support from friends, and support from parents. Given the dearth of research on friendships among Mexican-American youth, better understanding how friendships vary (or do not vary) as a function of key demographic variables will allow researchers to compare how such patterns may differ between youth from Mexican-American and other ethnic groups (based on past research with other ethnic groups) and to describe potential within-group variation. The second aim was to examine the extent to which perceived deviant and/or achievement-oriented friend affiliations are associated with adolescents’ school adjustment, including educational aspirations, attendance and academic problems. The final aim was to examine the extent to which associations between friend affiliations and school adjustment may depend on the strength of support perceived from friends and also from parents. For example, does greater friends’ support amplify the positive influence of achievement-oriented friends and the negative influence of deviant friends? Or does greater parental support protect Mexican-American high school students against the negative influence of affiliating with deviant friends?

To capture a thorough understanding of how friendships and parental support interact to influence adjustment, we examined multiple school adjustment outcomes, including educational aspirations as an indicator of achievement motivation (e.g., Ibañez et al. 2004) and attendance problems and academic problems as indicators of negative school behaviors. Moreover, this study included a sample of Mexican-American students during the first 2 years of high school. This is an important developmental period because, although it is a time when adolescents are becoming increasingly autonomous, parents continue to exert an influence on their high school students (Brown et al. 1993). Students’ experiences in their first year of high school can be influential in determining success for the rest of the high school years (National High School Center 2007). Finally, the focus on Mexican-Americans is a strength of this study because the sizeable demographic representation of Latino youth in the US is not yet reflected in the literature (Umaña-Taylor 2009). Additionally, Brown and Bakken (2011) indicate that ethnic-specific studies examining how parent and peer variables interact to predict adolescent outcomes would be useful to complement the predominance of studies with European–American youth.

Method

Participants

Participants were 412 adolescents (ages 14–16, M = 15.46, SD = 0.65) from Mexican or Mexican-American backgrounds. The sample was evenly split by gender (49.3 % male), and included 50 adolescents who were first-generation immigrants (i.e., they and their parents were born outside the US), 285 adolescents who were second-generation (i.e., they were born in the US, but at least one of their parents was not), and 77 adolescents who were third-generation or later (i.e., they and both of their parents were born in the US).

Procedure

Participants were recruited from the ninth and tenth grades of two public high schools (both schools spanned grades 9–12) in the Los Angeles area. In both schools, the majority of the student body was from Latin American backgrounds, but the student body of the first school was more diverse (60 % Latino, 18 % African American, 12 % Asian/Pacific Islander, 9 % White, not Hispanic, and 1 % other) than was the student body of the second school (94 % Latino, 2 % African American, 1 % Asian/Pacific Islander, 2 % White, not Hispanic, and 1 % other). Both schools served families who were from lower- to lower-middle class backgrounds; in both schools 71 % of the students qualified for free or reduced meals (California Department of Education 2012).

We obtained rosters for all ninth and tenth grade classrooms at both schools. Each week throughout the school year, we recruited students from a different, randomly selected group of classrooms. We presented the study to the students in these classrooms, and we also sent letters to students’ homes and called their parents to determine eligibility and interest. The current study is part of a larger study focusing on the daily lives of families from Mexican backgrounds. Thus, in addition to the requirement that they have Mexican heritage, adolescents could only participate in the current study if at least one of their primary caregivers was also willing to participate. Of the families who were determined to be eligible (i.e., they were reached by phone and self-reported a Mexican ethnic background), 63 % participated, which compares favorably with similarly intensive diary studies including Latino families (Updegraff et al. 2005). Of the primary caregivers who took part in this study, most were participants’ mothers (83 %) and the remaining were either participants’ fathers (13 %) or other caregivers (e.g., grandparents, uncles, aunts, etc.; 4 %).

The study took place in participants’ homes, and included two types of measures: questionnaires and daily checklists. Questionnaires included a variety of questions about life events, values, relationships, and well-being. Primary caregivers completed this questionnaire as an interview with a member of the research team; adolescents completed a paper-and-pencil version of this questionnaire independently. For completing this portion of the study, primary caregivers received $50, and adolescents received $30. After completing the questionnaire, adolescents received a 14-day supply of diary checklists, and they were instructed to complete one checklist each night before going to bed for a 2-week period. Each checklist took about 5–10 min to complete. To monitor on-time completion of the checklists, we provided participants with an electronic time stamper (a hand held device that imprints the current date and time and is programmed with a security code to prevent alterations to the correct date), and we instructed participants to fold, seal, and date-stamp each checklist upon completion. At the end of the 2 week period, a research team member collected participants’ checklists. If inspection of the data indicated that participants had completed the checklists correctly and on time, they received two movie passes. The time stamper monitoring and the movie pass incentives resulted in a high rate of compliance: 93 % of the possible 14 diaries were completed (M = 13.08, SD = 2.81), and the vast majority of these diaries (88 %) were completed on time (before noon of the following day). Analyses that were run to compare the results of models with only the checklists completed on time and all of the checklists revealed that the results remained the same. Thus, the findings in the results section include all of the completed checklists, whether or not they were completed on time. For the purposes of this study, only the ten school days were analyzed from the diaries. Primary caregivers also completed daily checklists, but their responses on these measures were not included in the current study.

Measures

Demographics

Adolescent demographic characteristics were taken from parents’ interviews. Parents reported their child’s birthdate, gender, and grade in school. Parents also reported their own and their child’s birthplaces, and we used these reports to determine each adolescent’s generational status.

Friend affiliations

We included two measures designed to tap the types of friends with whom participants reported affiliating: deviant friends’ affiliation and achievement-oriented friends’ affiliation. Both of these measures were drawn from the adolescent questionnaire.

Deviant Affiliation

This scale was designed to assess adolescents’ perceptions of the proportion of their friends who engage in deviant behaviors (Barrera et al., 2001). Participants read a list of 15 behaviors which ranged from relatively mild (e.g., got in trouble at school; started rumors or told lies) to relatively severe (e.g., use force to get things from people; stole something worth more than $50). Participants indicated how many of their friends engaged in each behavior during the past month (1 = none, 5 = almost all). On average, participants reported that between none and very few of their friends engaged in these behaviors (M = 1.56, SD = .59, α = .92).

Achievement-Oriented Affiliation

This scale was designed to assess adolescents’ perceptions of the proportion of their peers who are focused on achievement. This scale has been previously used in studies of high school students’ academic adjustment (Fuligni et al. 2001). Using a 5-point scale labeled from 1 (none) to 5 (almost all), participants responded to four items: During the past month, how many of your friends were… very ambitious?, planning to go to college?, doing well in school?, very hard working? On average, participants reported that between some and most of their friends had these characteristics (M = 3.36, SD = .79, α = .72).

Relational Support

We included two measures designed to tap the perceived quality of different relationships in participants’ lives: friends’ support (taken from the adolescent questionnaire) and parental support (taken from the parent interview).

Friends’ Support

With a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), participants indicated how often each of eight statements characterized their friendships in the past month (Armsden and Greenberg 1987). Sample items included: your friends respected your feelings, you told your friends about your worries and problems, and your friends showed that they understood you. Internal consistency for this measure, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha, was α = .92. The sample mean was 3.78 (SD = .88), which roughly corresponds to a lot of the time on the response scale.

Parental Support

Using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), parents indicated how often each of seven statements characterized their relationship with the participating adolescent in the past month (Armsden and Greenberg 1987). Sample items included: you respected [your child’s] feelings, you helped [your child] to talk about his/her difficulties, and you showed that you understood [your child]. Internal consistency for this measure was α = .81, and the sample mean (M = 4.19, SD = .70), which roughly corresponds with frequently on the response scale.

School Adjustment

Three measures of adolescents’ school adjustment were included: future education aspirations, attendance problems, and academic problems. Our measure of educational aspirations was drawn from the adolescent questionnaire; measures of attendance and academic problems were drawn from the daily checklist.

Future Education Aspirations

This measure (used previously in studies with Mexican-American adolescents; e.g., Gonzales et al. 2008) comprised a single item from the adolescent questionnaire. Adolescents answered the question: How far do you want to go in school? answered using a 1 (finish some high school) to 6 (graduate from law, medical or graduate school). Average aspirations were M = 4.99 (SD = 1.14), which corresponds to graduate from a 4-year college.

Attendance and Academic Problems

On each school day, participants indicated (yes/no) whether or not various activities or events happened. As a measure of daily attendance problems, we took the daily averages over the ten school days for the three items: had difficulty getting to school on time, was late for class, and skipped or cut a class. Thus, the variable represented the proportion of days out of 10 that the participant reported any one of the attendance problems. The sample mean was M = .16, which means that, on average, participants reported having attendance problems on 16 % of days (SD = .24). As a measure of daily academic problems, we averaged participants’ responses to one item (did poorly on a test, quiz, or homework) across all school days of the study. The sample mean was M = .14, which means that participants reported having academic problems on an average of 14 % of days (SD = .19).

Results

The study results are presented in three sections. First, we present the descriptive statistics and the intercorrelations among all of the measures of interest. Second, we report results from analyses of variance tests in which we examined differences in adolescents’ sources of support and friend affiliations based on their gender, grade and generational status. Finally, we present results from a series of hierarchical regression analyses in which we tested the extent to which friend affiliations account for between-person variance in school adjustment and whether friends’ support or parental support moderates these associations.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for all of the variables of interest. To explore general patterns of associations, intercorrelations were run among sources of support, friend affiliations and school adjustment (Table 1). Friends’ support was positively associated with achievement-oriented friend affiliation, but not with deviant friend affiliation. Conversely, parental support was negatively associated with deviant friend affiliation, but it was not associated with achievement-oriented friends. As may be expected, achievement-oriented and deviant friend affiliations were negatively correlated. That is, adolescents with a greater proportion of achievement-oriented friend affiliations tended to have a lower proportion of deviant friend affiliations (and vice versa). Among the school adjustment variables, there were only a few significant correlations. There was a positive association between attendance problems and academic problems, suggesting that students who have more attendance problems also have more academic problems. At the bivariate level, achievement-oriented friend affiliations, friends’ support, and parental support were all positively correlated with educational aspirations. None of the friend affiliation or sources of support variables were associated with either attendance or academic problems.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations among primary measures of interest

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friend affiliations | |||||||

| Deviant | - | ||||||

| Achievement-oriented | −.18*** | - | |||||

| Sources of support | |||||||

| Friend support | −.09 | .38*** | - | ||||

| Parent support | −.14** | .09 | −.04 | - | |||

| School adjustment | |||||||

| Educational aspirations | −.10 | .19*** | .10* | .12* | - | ||

| Attendance problems | −.02 | .03 | .03 | .05 | .01 | - | |

| Academic problems | .05 | .04 | .07 | −.00 | −.02 | .21*** | - |

All of the measures were self-reports from adolescents, except for parental support, which was gathered from the adolescent’s primary caregiver

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Gender, Grade, and Generational Status Differences in Friendship and Parent Factors

Differences in Mexican-American adolescent’s reports of friends’ support, parental support, deviant friend affiliation, and achievement-oriented friend affiliation based on their gender, grade and generational status were tested with analysis of variance tests. A main effect of gender emerged for perceived friend support, F(1, 399) = 39.60, p < .001, η2 = .09, such that girls (M = 4.14, SD = .72) reported higher friends’ support than boys (M = 3.42, SD = .88). There were no differences in friends’ support based on grade or generational status, and none of the interactions were significant. Also, no significant differences based on gender, grade or generational status emerged for parent support or deviant friend affiliations. Finally, for achievement-oriented friend affiliation, there was a main effect of gender, F(1, 398) = 7.14, p = .008, η = .02. Specifically, girls (M = 3.46, SD = .79) reported more achievement-oriented affiliations than boys (M = 3.26, SD = .78). Reports of achievement-oriented affiliations did not differ by either grade or generational status.

Testing the Moderating Role of Support from Friends and Parents

A set of three regression models were run to examine how the proportions of deviant and achievement-oriented friend affiliations were associated with each of the school adjustment outcomes. Furthermore, regressions tested the hypotheses that the associations between deviant friend affiliations and achievement-oriented friend affiliations with school adjustment varies as a function of friends’ support and/or parental support. The results from the three regression models are presented in Table 2. In the first step of each of these analyses, we controlled for demographic differences by including gender (dummy coded: males as the comparison group), grade (dummy coded: ninth-grade students as the comparison group), and generational status (dummy coded: third-generation students as the comparison group). School differences were also accounted for in the first step. In the second step, we included the two friend affiliation factors, friends’ support and parental support to examine their main effects on school adjustment. In the third step, four cross-products (i.e., friends’ support × deviant friend affiliation, friends’ support × achievement-oriented friend affiliation, parental support × deviant friend affiliation, and parental support × achievement-oriented friend affiliation) were entered. These cross products allowed us to examine the potential moderations, for example, whether the level of support from friends weakens or strengthens the associations between deviant or achievement-oriented friend affiliations with school adjustment. Additional models with three-way interactions between friend affiliations, friends’ support and parental support were tested. However, given that these interactions were non-significant across all of the outcomes, they were removed from the final models that are presented. To avoid multicollinearity (Fairchild and McQuillin 2010) and to ease the interpretation of lower-order coefficients if significant interactions emerged (Aiken and West 1991), the friendship affiliation and support variables were centered for all analyses.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression analyses with friend support, parent support and friend affiliations

| Variable | Educational aspirations |

Attendance problems |

Academic problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||

| Gender | .14** | .14* | −.06 |

| Grade | .03 | .00 | .16** |

| First generation | .15* | −.07 | .01 |

| Second generation | .12* | −.01 | .04 |

| School | −.06 | .01 | −.05 |

| Step 2 | |||

| Friend support | .00 | .00 | .12 |

| Parent support | .10* | .03 | .02 |

| Deviant affiliation | −.02 | −.00 | .12* |

| Achievement affiliation | .16** | .02 | .02 |

| Step 3 | |||

| Friend support × DA | −.06 | .01 | .15** |

| Friend support × AA | .10* | .06 | .07 |

| Parent support × DA | .07 | −.04 | .10 |

| Parent support × AA | −.13* | .02 | −.06 |

| Total R2 | .11*** | .03 | .08* |

All reported βs are standardized regression coefficients from the final step of the model

DA deviant friend affiliation, AA achievement-oriented friend affiliation

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Educational Aspirations

The final model including the controls (i.e., gender, grade, generational status, and school), the friendship and support factors entered at the second step, and the cross-products at the final step, accounted for a significant 11 % of the variance in adolescents’ educational aspirations, F(13, 376) = 3.74, p < .001. As shown in Table 2, among the controls, gender, first generation and second generation were associated with educational aspirations. Specifically, girls had higher educational aspirations than boys, and first-and second-generation Mexican-American teens had higher aspirations than third-generation teens. After accounting for the control variables, there were main effects of parental support and achievement-oriented friend affiliation—adolescents with more supportive parents and adolescents with more achievement-oriented affiliations reported higher educational aspirations. However, these findings were qualified by two significant interactions: an interaction between support from friends and achievement-oriented friend affiliation and an interaction between parental support and achievement-oriented friend affiliation.

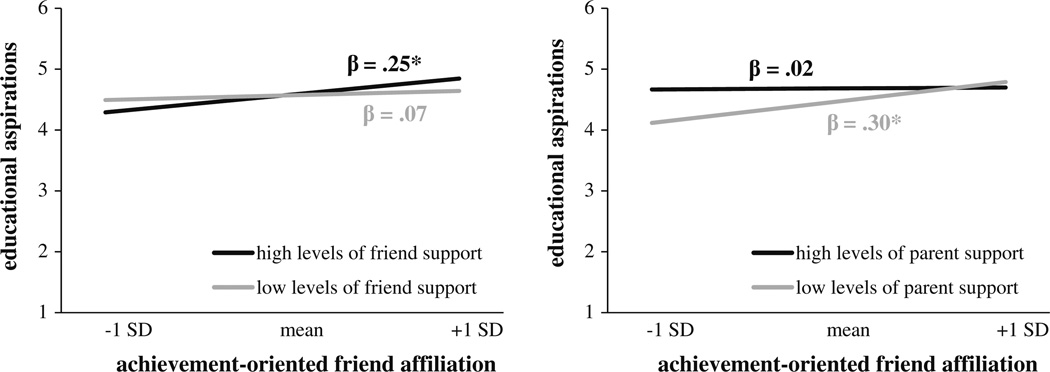

First, we followed up the interaction between friends’ support and achievement-oriented friend affiliation on educational aspirations by using simple slope analysis (Aiken and West 1991). Given the pattern of the moderation, it was most appropriate to probe the association between achievement- oriented friend affiliation and educational aspirations as a function of friends’ support. To this end, we first created two new friends’ support variables: one recentered at one standard deviation below the sample mean, and one recentered at one standard deviation above the sample mean. We then re-ran the model described above with each of these recentered friends’ support variables (and corresponding interaction terms) in turn. As shown in the left panel of Fig. 1, at low levels of support from friends, achievement-oriented friend affiliations did not predict student’s educational aspirations (β = .07, p = .33). At high levels of support from friends, however, having more achievement-oriented affiliations was predictive of higher educational aspirations (β = .25, p = .001). In other words, affiliating with friends who are ambitious and hard-working was only associated with higher educational aspirations among adolescents who reported high levels of friend support. Overall, the students who had a high proportion of achievement-oriented friend affiliations and high levels of support from friends were the ones who reported the highest educational aspirations.

Fig. 1.

Friends’ support and parental support moderate the association between achievement-oriented friends and educational aspirations. *p < .001

Next, we used the same analytical strategy to follow up the interaction between parental support and achievement-oriented friend affiliation on educational aspirations. As shown in the right panel of Fig. 1, the positive association between achievement-oriented affiliations and educational aspirations only held among adolescents with low levels of parental support (β = .30, p < .001). At high levels of parental support, there was no significant association between adolescents’ achievement-oriented affiliations and their educational aspirations(β = .02, p = .84). In other words, affiliating with friends who are ambitious and hard-working was only associated with higher educational aspirations among adolescents who reported low levels of parental support. Phrasing the pattern of this interaction another way, with a high proportion of achievement-oriented friends, the educational aspirations among adolescents with high and low levels of parental support were similar. With a low proportion of achievement-oriented friends, however, educational aspirations were significantly higher among adolescents who also have high levels of parental support as compared with those with low levels of support from parents.

Attendance Problems

The model with the controls, friend affiliations, and support factors did not account for a significant amount of the variance in student’s attendance problems, F(13, 313) = .77, p = .69. That is, friend affiliations and support were not predictive of whether students arrived to class late or skipped class. The cross-products were non-significant as well.

Academic Problems

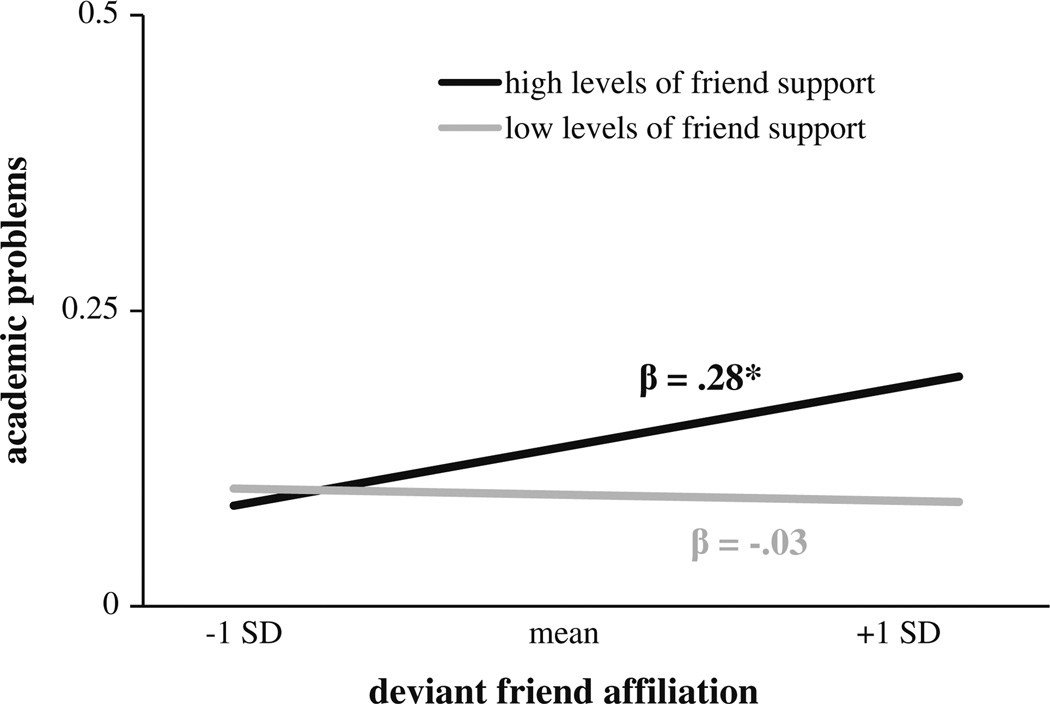

Overall, a significant 8 % of the variance in student’s academic problems was explained by the model, F(13, 313) = 1.98, p = .02. Of the control variables, grade level was significant: students in the tenth grade reported more academic problems compared to ninth-grade students. There was a main effect of deviant friend affiliations such that students who reported affiliating with more deviant friends were also more likely to report academic problems. This main effect, however, was qualified by a significant interaction between friends’ support and deviant friends’ affiliation (see Table 2). Follow-up tests revealed that the association between deviant affiliations and academic problems was not significant among adolescents who reported low levels of support from friends(β = −.03, p = .71), but this association was significant among adolescents who reported high levels of support from friends (β = .28, p = .001; see Fig. 2). Students who affiliated with more deviant friends and who reported high levels of friends’ support were the most likely to report having academic problems.

Fig. 2.

Friends’ support moderates the association between deviant friends and academic problems. Note *p < .001

Discussion

Overall, there is a limited understanding of how friend affiliations and support from both friends and parents may be related to school adjustment among Mexican-American high school students. In the context of the many educational barriers that Mexican-American youth face, parental support and positive peers may be especially important. The aim of this study was to examine the role of achievement-oriented and deviant friend affiliations in predicting Mexican-American adolescents’ school adjustment, including academic aspirations and negative school behaviors. Guided by the ecological theory perspective (Bronfenbenner 1979), this study also tested whether associations between friend affiliations and school adjustment vary as a function of two important interpersonal relationship factors: friends’ support and parental support. Given that research on Mexican-American adolescents’ poor school adjustment often focuses on home and family factors or on the negative influence of peers, the current study extends research by illustrating both the positive and negative role that friends may play. Most importantly, the findings highlight that simply examining the extent to which friend affiliations are associated with school outcomes does not fully capture how friends promote or hinder motivation and school behaviors. That is, the extent to which affiliating with achievement-oriented or deviant friends were related to educational aspirations and academic problems depended on levels of friends’ support and/or levels of parental support. Specifically, the influence of peer affiliation was greatest when peer relationships were highly supportive and parent relationships were low on support (Fuligni and Eccles 1993).

At a descriptive level, few differences in the friendship factors were found based on the gender, grade or generational status of Mexican-American adolescents. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Colarossi and Eccles 2000; Furman and Buhrmester 1992), girls reported higher levels of friends’ support compared to boys. Moreover, also consistent with previous research (Liu 2004), girls reported more achievement-oriented friends affiliations compared to boys. In sum, although there were only differences based on gender, these findings help us better classify and understand friendships among Mexican-American youth. The results reveal that there may be few within-group differences in friendship factors among Mexican-American youth, at least with respect to grade and generation status differences.

Only a few direct associations between deviant and achievement-oriented friend affiliations with the school adjustment indicators emerged. Affiliating with a greater proportion of achievement-oriented friends was associated with higher educational aspirations and higher deviant friend affiliations were related to more academic problems. Thus, interpreting only the main effects of affiliations alone may suggest that whether Mexican-American adolescents affiliate with deviant or achievement-oriented friends is inconsistently associated with school adjustment. However, the interaction findings indicate that the extent to which friend affiliations are linked to school outcomes depends on levels of support from friends and also parental support.

More specifically, the findings highlight that it is at high levels of support from friends that the positive and negative influence of friend affiliations are associated with school outcomes. Achievement-oriented friend affiliations were positively related to academic aspirations (i.e., how far students want to go in school), only at high levels of friend support. This finding is consistent with the social development model (Catalano and Hawkins 1996), which emphasizes the importance of strong support bonds and attachment for determining the salience of social influences, including positive and negative influences. Thus, for Mexican-American students to reap the most academic motivation benefits from their friends, it is not merely enough to just affiliate with achievement-oriented friends or to only perceive high levels of support; rather, it is the combination of these factors that is optimal. These findings are important because they help, in part, clarify the inconsistent findings from past research on friendships with Latino youth (e.g., Garcia-Reid et al. 2005; Garcia-Reid 2007).

Additionally, a significant interaction with friends’ support revealed that greater affiliation with deviant friends is associated with more academic problems, only at high levels of support from friends. Thus, it is the students who perceive high levels of support from friends and affiliate with deviant friends who report more instances of doing poorly on a test, quiz or homework. Chester et al. (2007) have suggested that friends’ support may not necessarily be beneficial to adolescents, particularly in instances when support is provided for deviant behaviors. These results illustrate that deriving less support from peers may be adaptive in the context of deviant networks and may be one way for youth in contexts dominated by deviant peers to resist influence and deviancy training associated with delinquent peer groups (e.g., Dishion and Dodge 2005). In addition, this may be particularly important for Mexican-American youth in communities, or more specifically, schools, that are often characterized by deviant models and lacking in positive models demonstrating that academic success leads to occupational success. Overall, the findings indicate that whether high support from friends will be beneficial or detrimental to educational aspirations and school behaviors may depend on whom the friends are. In the current study, adolescents reported on their perceived general friend support, not the particular levels of support, companionship or understanding they receive specifically from their deviant friends. Future research should ask students about the levels of support they receive from particular types of friends to draw more concrete conclusions about how support is tied to positive or negative influences from friends.

Parental support was also found to modify the association between achievement-oriented friends and educational aspirations, however the pattern differed from the model with friend support. At high levels of parental support, the incremental effects of friend affiliations on aspirations and expectations were non-significant. That is, if adolescents are receiving support from parents, their levels of educational aspirations remain high whether they have a small or large proportion of achievement-oriented friends. Thus, students with high levels of parental support may not require the influence of their achievement-oriented friends to remain academically motivated. However, at low levels of support, youth are unlikely to report higher aspirations unless they affiliate with achievement oriented friends. Why is it that when parents provide little support to their adolescents, having a greater proportion of achievement-oriented friends is linked to academic motivation? Fuligni (1997) suggests that when examining the school adjustment of Latino immigrant students, it becomes particularly important to consider the dynamic role that friends may play because parents are often unfamiliar with the educational system in the US and thus, friends become an important source of influence and support. It may be the case that when parents are not providing support such as showing their child that they understand them and helping them with difficulties, teens are more susceptible to the influence of their friends. Although the negative susceptibility to friends is often considered, these results show that achievement-oriented friends may positively counterweigh a lack of parental support, at least in regard to adolescents’ academic aspirations. Furthermore, if achievement-oriented friends are considered a form of social capital (Crosnoe et al. 2003), then this capital may be especially beneficial for adolescents who lack support from parents. Future studies that specifically examine support from parents towards school and academics or parent–child communication regarding school would further elucidate the dynamics between parents and peers in regard to promoting aspirations. Interestingly, in the three-way interactions with friend affiliation and support from both parents and friends, no significant results emerged. Additional studies should further test these complex interactions to better understand if the non-significant results are due to a lack of power to detect such findings or whether indeed it is the case that associations between perceived friend affiliations and school adjustment do not vary systematically as a function of both support from parents and peers.

There are several ways in which this study extends previous research. For example, the use of not only self-reports but also parent report (which helps diminish concerns about shared method variance) and the use of multiple indicators of school adjustment across two methods (i.e., questionnaire, daily diaries) are strengths of the study. Moreover, the focus on the early high school years is a strength, given that this is a key developmental period for academics (National High School Center 2007). However, there are also limitations of the study that should be noted. Although the use of both educational aspirations and school behavior indicators is an asset of the study, other important school adjustment indicators were not examined. For example, perceptions of the school climate such as school safety have been highlighted as particularly important for Latino students (Espinoza and Juvonen 2011; Gándara and Contreras 2009). Also, whether parents and friends interact in similar ways to predict more distal school outcomes such as grades and retention rates would provide a more thorough understanding of how these relationships are associated with more objective school outcomes. For example, the measure of academic problems that relied on student reports may be considered subjective. It might be the case that a high-achieving A student who receives a B on a quiz might rate themselves as having done poorly whereas a low-achieving student who also receives a B grade on a quiz might not indicate that they did poorly. In addition, given that the predictor variables accounted for a low proportion of the variance in school adjustment, it is important to examine whether friend affiliations and perceived support are more predictive of objective school outcomes. However, past research has highlighted the low variance accounted for by friendship variables and indicated that although friends play an important role in school adjustment, they may not have as strong of an influence compared to other influences (e.g., Berndt 1999). Also related to the methodology, by requiring that parents also participate in the study, it is likely that a group of families (perhaps those with adolescents most at-risk for school failure) self-selected to not participate in the study. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of these data limits the possibility of testing causal relationships. For example, child effects research (e.g., Larsson et al. 2008; Lytton 1990) shows that child characteristics or behaviors evoke different reactions from parents. That is, parents may be more trusting and understanding of adolescents who do well in school and who have high educational aspirations and expectations, compared to parents of teens who have low academic motivation. Longitudinal data would allow the testing of bidirectional associations between friend affiliations and parent and friends’ support with school adjustment.

Conclusion

Given the dire scholastic prospect for many Latino students living in the US, and for Mexican-American students in particular, it is important to comprehend how to best promote positive school outcomes for these students. Overall, we found support for our hypotheses that the patterns of association between friend affiliations and school adjustment are complex, and that the extent to which friend affiliations are linked to students’ school feelings or behaviors may vary as a function of support from friends and parents. Specifically, Mexican-American high school students’ peer affiliations were associated with differences in educational aspirations and negative school behaviors, especially when they reported high levels of support from friends or low levels of parental support. Furthermore, although results showed that deviant friends are associated with greater academic problems (in combination with high friend support), this study also illuminates the positive role that peers and friends can play in adolescents’ school outcomes. Indeed, as the ecological framework would predict, parent and peer relations intersect in important and meaningful ways (Brown and Bakken 2011). Thus, future research that aims to extend our understanding of adolescents’ school adjustment will benefit from considering the dynamic function of multiple interpersonal relationships.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding through the National Institute of Child and Human Development (R01HD057164). We would like to thank the school principals, teachers and students for their participation in this project.

Biographies

Guadalupe Espinoza is an Assistant Professor in the Child and Adolescent Studies Department at California State University, Fullerton. She received her doctorate in Developmental Psychology from UCLA. Her major research interests include adolescent’s social interactions with peers in both the school and online contexts, with a particular focus on ethnic minority youth from Latin American backgrounds.

Cari Gillen-O’Neel is currently a graduate student in developmental psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles. She examines the educational implications of social psychological and social cognitive development.

Nancy A. Gonzales is ASU Foundation Professor of Psychology and Director of the Prevention Research Center at Arizona State University. Her research examines cultural and contextual influences on the social, academic and psychological development of children in low income communities. The ultimate aims of this work are to advance understanding of how children adapt to the demands of their immediate social environments, and to translate finding into community-based intervention that are effective at promoting successful adaptation and reducing health disparities for high-risk youth and families.

Andrew J. Fuligni is a Professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. He received his doctorate in Developmental Psychology from the University of Michigan. His major research interests include adolescent development and social relationships among Asian, Latino, and immigrant families.

Footnotes

Author contributions GE participated in the design and coordination of the study, performed statistical analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and primarily authored the manuscript. CG participated in the design and coordination of the study, assisted with statistical analyses, and provided feedback on drafts of manuscript. NG acquired funding for the study, participated in the design and coordination of the study, assisted with analyses and interpretation of data and provided feedback on drafts of manuscript. AF acquired funding for the study, participated in the design and coordination of the study, and provided feedback on drafts of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Guadalupe Espinoza, Child and Adolescent Studies Department, California State University, Fullerton, 800 N State College Blvd., P.O. Box 6868, Fullerton, CA 92834, USA, guadespinoza@fullerton.edu.

Cari Gillen-O’Neel, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Nancy A. Gonzales, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Andrew J. Fuligni, Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

References

- Agnew R. The interactive effects of peer variables on delinquency. Criminology. 1991;29:47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16:427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia M, Cooper CR. Good or bad? peer influences on Latino and European American adolescents’ pathways through school. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk. 2001;6:45–71. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Jr, Biglan A, Ary D, Li F. Replication of a problem behavior model with American Indian, Hispanic, and Caucasian adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:133–157. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Jr, Gonzales NA, Lopez V, Fernandez AC. Problem behaviors of Chicana/o and Latina/o adolescents: An analysis of prevalence, risk, and protective factors. In: Velasquez RJ, Arellano LM, McNeill BW, editors. The Handbook of Chicana/o psychology and mental health. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Friends influence on students’ adjustment to school. Educational Psychologist. 1999;34:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Keefe K. Friends’ influence on adolescents’ adjustment to school. Child Development. 1995;66(5):1312–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Bakken JP. Parent and peer relationships: Reinvigorating research on family-peer linkages in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(1):153–165. [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, Mounts N, Lamborn SD, Steinberg L. Parenting practices and peer group affiliation in adolescence. Child Development. 1993;64(2):467–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Mesa LMS. The study of sex, gender, and relationships with peers: A full or empty experience? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2007;53(3):507–519. [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Education. Data Quest: Enrollment Data. 2012 Retrieved February 24, 2012, from http://dq.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/.

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chester C, Jones DJ, Zalot A, Sterrett E. The psychosocial adjustment of African American youth from single mother homes: The relative contribution of parents and peers. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36(3):356–366. doi: 10.1080/15374410701444306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colarossi LG, Eccles JS. A prospective study of adolescents’ peer support: Gender differences and the influence of parental relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29(6):661–678. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CE, Crosnoe R. The engagement in schooling of economically disadvantaged parents and children. Youth and Society. 2007;38:372–391. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Cavanagh S, Elder GH. Adolescent friendships as academic resources: The intersection of friendship, race and school disadvantage. Sociological Perspectives. 2003;43(3):331–352. [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS, Martinez CR. A culturally informed model of academic well-being for Latino youth: The importance of discriminatory experiences and social support. Family Relations. 2006;55:267–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Dodge KA. Peer contagion in interventions for children and adolescents: Moving towards an understanding of the ecology and dynamics of change. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33(3):395–400. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Bonds DD, Millsap RE. Academic success of Mexican origin adolescent boys and girls: The role of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting and cultural orientation. Sex Roles. 2009;60:588–599. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eamon MK, Mulder C. Predicting antisocial behavior among Latino young adolescents: An ecological systems analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75(1):117–127. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza G, Juvonen J. Perceptions of the school social context across the transition to middle school: Heightened sensitivity among Latino students? Journal of Educational Psychology. 2011;103(3):749–758. [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AJ, McQuillin SD. Evaluating mediation and moderation effects in school psychology: A presentation of methods and review of current practice. Journal of School Psychology. 2010;48:53–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frauenglass A, Routh DK, Pantin HM, Mason CA. Family support decreases influence of deviant peers on Hispanic adolescents’ substance use. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26(1):15–23. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. The academic achievement of adolescents from immigrant families: The roles of family background, attitudes and behavior. Child Development. 1997;68(2):351–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Eccles JS. Perceived parent-child relationships and early adolescents’ orientation toward peers. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(4):622–632. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Eccles JS, Barber BL, Clements P. Early adolescent peer orientation and adjustment during high school. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37(1):28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63(1):103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gándara P, Contreras F. The Latino education crisis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Reid P. Examining social capital as a mechanism for improving school engagement among low income Hispanic girls. Youth and Society. 2007;39(2):164–181. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Reid P, Reid RJ, Peterson NA. School engagement among Latino youth in an urban middle school context: Valuing the role of social support. Education and Urban Society. 2005;37(3):257–275. [Google Scholar]

- Germán M, Gonzales NA, Dumka L. Familism values as a protective factor for Mexican-origin adolescents exposed to deviant peers. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(1):16–42. doi: 10.1177/0272431608324475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Germán M, Kim SY, George P, Fabrett FC, Millsap R, et al. Mexican American adolescents’ cultural orientation, externalizing behavior and academic engagement: The role of traditional cultural values. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:151–164. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9152-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Iban˜ez GE, Kuperminc GP, Jurkovic G, Perilla J. Cultural attributes and adaptations linked to achievement motivation among Latino adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33(6):559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Kingery JN, Erdley CA, Marshall KC. Peer acceptance and friendship as predictors of early adolescents’ adjustment across the middle school transition. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2011;57(3):215–243. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H, Viding E, Rijsdijk FV, Plomin R. Relationships between parental negativity and childhood antisocial behavior over time: A bidirectional effects model in a longitudinal genetically informative design. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:633–645. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RX. Parent-youth conflict and school delinquency/ cigarette use: The moderating effects of gender and associations with achievement-oriented peers. Sociological Inquiry. 2004;74:271–297. [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H. Child and parent effects in boys’ conduct disorder: A reinterpretation. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:683–697. [Google Scholar]

- Muuss RE. Theories of adolescence. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. The condition of education 2013. 2013 NCES 2013-037), Status Dropout Rates. [Google Scholar]

- National High School Center, American Institutes for Research. Approaches to dropout prevention: Heeding early warning signs with appropriate interventions. 2007 Retrieved from www.betterhighschools.org/docs/nhsc_approachestodropoutprevention.pdf.

- Pew Hispanic Research Center. Statistical portrait of Hispanics in the United States 2009. 2011 Retrieved from http://pewhispanic.org/factsheets/factsheet.php?factsheetID=70.

- Ream RK, Rumberger RW. Student engagement, peer social capital, and school dropout among Mexican American and non-Latino White students. Sociology of Education. 2008;81:109–139. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Dwyer KM, Booth-LaForce C, Kim AH, Burgess KB, Rose-Krasnor L. Attachment, friendship, and psychosocial functioning in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24(4):326–356. doi: 10.1177/0272431604268530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumberger RW, Larson KA. Toward explaining differences in educational achievement among Mexican American language-minority students. Sociology of Education. 1998;71(1):68–92. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ. Daily family assistance and the psychological well-being of adolescents from Latin American, Asian and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(4):1177–1189. doi: 10.1037/a0014728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turney K, Kao G. Barriers to school involvement: Are immigrant parents disadvantaged? Journal of Educational Research. 2009;102:257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Uman˜a-Taylor AJ. Research with Latino early adolescents: Strengths, challenges, and directions for future research. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29(1):5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, McHale SM, Whiteman SD, Thayer SM, Delgado MY. Adolescent sibling relationships in Mexican American families: Exploring the role of familism. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:512–522. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. School enrollment. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley ME, Kol KL, Bowen GL. The social context of school success for Latino middle school students: Direct and indirect influences of teachers, family, and friends. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Richman JM, Bowen GL, Woolley ME. School failure: An eco-interactional developmental perspective. In: Fraser MW, editor. Risk and resilience in childhood: An ecological perspective. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: NASW Press; 2004. pp. 133–160. [Google Scholar]