Abstract

The chloroform extract of the stem bark of Amburana cearensis was chemically characterized and tested for antibacterial activity.The extract was analyzed by gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. The main compounds identified were 4-methoxy-3-methylphenol (76.7%), triciclene (3.9%), α-pinene (1.0%), β-pinene (2.2%), and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (3.1%). Preliminary antibacterial tests were carried out against species of distinct morphophysiological characteristics: Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica Serotype Typhimurium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, and Bacillus cereus. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determinate in 96-well microplates for the chloroform extract and an analogue of themain compound identified, which was purchased commercially.We have shown that plant's extract was only inhibitory (but not bactericidal) at the maximum concentration of 6900 μg/mL against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacillus cereus. Conversely, the analogue 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol produced MICs ranging from215 to 431 μg/mL against all bacterial species.New antibacterial assays conducted with such chemical compound against Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing strains have shown similarMICresults and minimumbactericidal concentration (MBC) of 431 μg/mL.We conclude that A. cearensis is a good source of methoxy-methylphenol compounds,which could be screened for antibacterial activity againstmultiresistant bacteria fromdifferent species

1. Introduction

Amburana cearensis (Allemão) A.C. Sm. (Fabaceae) is a native plant from Brazilian semiarid region widely used in folk medicine to treat nervous disorders, headaches, asthma, sinusitis, bronchitis, flu, and rheumatic pain, with the stem bark and seeds commonly being consumed as tea or infusion preparations [1–3]. The stem bark is rich in coumarin (1,2-benzopyrone), whose pharmacological properties include anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, and bronchodilator effects [4–7]. Indeed, four new compounds (p-hydroxybenzoic acid, aiapin, and two stereoisomers of o-coumaric acid glycoside) were recently identified, showing plants' repertory of potential bioactive substances [8]. However, although A. cearensis has been broadly used in treatment of respiratory infections, only a few studies report antimicrobial activity in plants' extracts [9, 10], and, therefore, its potential as a source of new antimicrobials was not fully investigated.

The spread of multidrug resistance among bacteria from various sources [11–16] has made natural product researchers increase their effort on screening plant extracts for compounds with broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity. For example, Tragia involucrata L., Citrus acida (Roxb. Hook.f.), and Aegle marmelos (L.) Correa ex Roxb. showed wide inhibitory action against several multidrug-resistant human pathogens, particularly, Burkholderia pseudomallei and Staphylococcus aureus, which was related to the high contents of phenolic or polyphenolic compounds in methanol extracts [17, 18]. Likewise, recent antibacterial assays with stem bark ethanol extracts of A. cearensis have shown growth inhibition of a broad range of pathogens of veterinary interest [10]. In particular, hospital-acquired infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae (Enterobacteriaceae) have increased in recent years due to emergence of carbapenemase- producing strains [19, 20]. These bacteria are capable of hydrolyzing carbapenems, penicillins, cephalosporins, and aztreonam [21], and, therefore, the search for new therapeutics is forthcoming.

Here, a preliminary assessment of the antibacterial activity of A. cearensis chloroform extracts against human clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing strains was conducted. Moreover, the plants' extract was chemically characterized and an analogue of the major compound identified was also tested against bacteria. Although the chemical composition of plant extracts varies under influence of seasonal and climatic conditions [22], in the present study, we report A. cearensis as a new source of methoxy-methylphenol compounds with antibacterial activity. These are phenol derivatives with potential applications as antiseptics and biocides. These data are discussed in light of previous studies.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Collection and Botanical Identification

The stem bark of A. cearensis was collected in the municipality of Salgueiro, Pernambuco, Brazil (latitude 08°04′27′′ south and longitude 39°07′09′′ west). The plant's identification was made by comparing the aerial parts with exsiccate samples (voucher number 46090) deposited in the collection of Vasconcelos Sobrinho Herbarium, Department of Biology, Federal Rural University of Pernambuco, under the care of Dr. Suzene Izidio da Silva.

2.2. Plant Extract

Fresh plant material was collected and dried in oven at a temperature range of 45°C to 50°C for 48 h. The dried material was ground in a blade mill to obtain a fine homogeneous powder. This material was weighed and extracted by maceration using chloroform (P.A.) as solvent extractor in the ratio of 1 : 3 (w : v). The resulting mixture remained for 48 hours under agitation every two hours. The extract was filtered and concentrated in a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure at a temperature of 45°C for complete solvent removal. Stock solutions were prepared with extracts using dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as solvent (100 mg/mL), which were kept in a refrigerator at −20°C until use [23].

2.3. Analysis by Gas Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry (GS/MS)

The plant extract was analyzed by GS/MS using a Varian 431-GC chromatograph coupled to a Varian 220-MS mass spectrometer, equipped with a J & W Scientific DB5 fused silica capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 mm). The temperature of the injector and detector was set at 260°C with the furnace temperature programmed in a range of 60–240°C at 3°C/min. The mass spectra were obtained with a 70 eV electron impact, 0.84 scan/sec m/z 40–550. The carrier gas used was helium at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. A stock solution of 2 mg/mL was prepared and 1.0 μL was injected for analyses. The identification of the constituents was carried out by comparison with previously reported values of retention indices, obtained by coinjection of oil samples and C11–C24 linear hydrocarbons and calculated using the van Den Dool and Kratz equation [24], by direct comparison of the spectra with spectra stored in libraries of equipment (NIST21 and NIST107) as well as with the spectra and retention times of authentic compounds reported previously in the literature for comparison. Subsequently, the MS acquired for each component was matched with those stored in the NIST21, NIST107 mass spectral library of the GC-MS system and with other published mass spectral data [25].

2.4. Microorganism and Growth Conditions

Preliminary assessment of antibacterial activity was conducted with bacteria of distinct morphophysiological characteristics, such as Escherichia coli (facultative anaerobe, gram-negative, nonencapsulated, extracellular bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae), Salmonella enterica Serotype Typhimurium (facultative anaerobe, gram-negative, nonencapsulated, intracellular bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (aerobe, gram-negative, extracellular bacteria, non-Enterobacteriaceae), Staphylococcus aureus (facultative anaerobe, gram-positive, non-spore-forming, extracellular bacteria), Listeria monocytogenes (facultative anaerobe, gram-positive, non-spore-forming, intracellular bacteria),and Bacillus cereus (aerobe, gram-positive, spore-forming, extracellular bacteria) belonging to the collection of the Laboratory of Microbiology and Immunology of Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (UFRPE). Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenem-resistant strains (KPC) were obtained from human clinical cases and kindly provided by Dr. Marcia Moraes (University of Pernambuco). Single colonies from fresh cultures were streaked in tubes containing Brain Heart Infusion Agar after growth (37°C/18–24 h) and kept at 8°C until use.

2.5. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

The MIC of the plant extract was determined by the microdilution method [34] in 96-well plates at concentrations ranging from 6.7 to 6900 µg/mL. In addition, the analogue 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol of the main compound identified in plant extracts (4-methoxy-3-methylphenol) was purchased commercially (Sigma) and also investigated. The density of the bacterial suspension was adjusted to approximately 105 CFU/mL, and the results were read after an incubation period of 24 hours at 37°C. The MIC was the lowest concentration causing inhibition of visible growth. In this case, aliquots of 0.1 mL were transferred to plates containing Mueller-Hinton agar. The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was considered the lowest concentration that resulted in no growth after incubation for 24 h at 37°C. All assays were performed in duplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

The Brazilian floras are worldwide known as a source of biologically active compounds with biodegradable properties, and, therefore, screening of plant extracts is often a first step procedure for isolation of phytochemicals [23]. However, studies that correlate antibacterial activity of extracts to the presence of specific compounds are rare. For instance, ethanol extracts of the stem bark of A. cearensis were reported to be inhibitory against Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. aureus, Klebsiella spp., Salmonella spp., Enterobacter aerogenes, Streptococcus pyogenes, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Shigella flexneri, but no chemical characterization was performed [10]. Here, we report the phytochemistry and preliminary assessment of A. cearensis chloroform extracts as a source of novel antimicrobials against multiresistant Klebsiella strains.

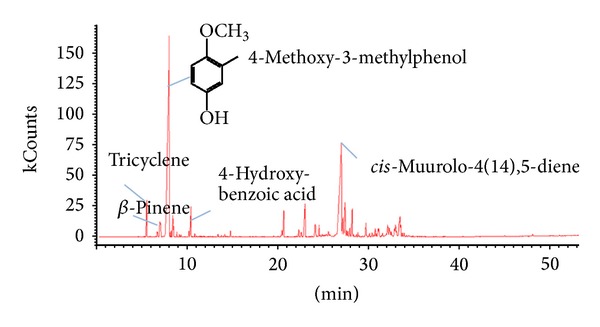

The GC/MS data showed a major peak at the retention time of 7.8 min with relative concentration of 76.7% (Figure 1). The interpretation of the mass spectra in comparison with spectra reported in the literature led to identification of the benzenoid 4-methoxy-3-methylphenol. Other compounds included tricyclene (3.9%), α-pinene (1.0%), β-pinene (2.2%), and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (3.1%). The complete list of compounds identified in plants' extract is reported in Table 1. Several compounds have been identified in the bark of A. cearensis, such as trans -3,4-methyl dimetoxicinamato, cis-3,4-dimethoxy-methyl cinnamate, 3-methoxy-4-hydroxy-methyl cinnamate, 4-hydroxy-methyl benzoate, 3,4-dihydroxy methyl benzoate, 3-hydroxy-4-methoxy methyl benzoate, catechol, guaiacol, a-ethoxy-p-cresol, benzenemethanol 4-hydroxy, 4-methoxy-methylphenol, 2,3-dihydrobenzofuran, and anthraquinone (chrysophanol), with predominance of coumarins being often reported [35].

Figure 1.

Chromatogram of chloroform extract of the stem bark of A. cearensis.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the chloroform extract of the stem bark of Amburana cearensis.

| Compoundsa | Relative area (%) | RIb | RIc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tricyclene | 3.9 | 919 | 921 |

| α-Pinene | 1.0 | 931 | 932 |

| β-Pinene | 2.2 | 974 | 974 |

| 6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl | 2.3d | — | — |

| 4-Methoxy-3-methylphenol | 76.7d | — | — |

| Terpinolene | 0.3 | 1087 | 1088 |

| 1,3,8-p-Menthatriene | 0.5 | 1107 | 1108 |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 3.1d | — | — |

| Longifolene | 1.7 | 1405 | 1407 |

| cis-Muurolo-4(14),5-diene | 3.2 | 1462 | 1465 |

|

| |||

| Total | 94.9 | — | — |

aCompounds are listed in order of their elution from a DB-5 column; bRI = retention indices relative to C7–C30 n-alkanes; cRI = retention indices from the literature. dIdentified by direct comparison of the spectra with spectra stored in libraries of equipment as well as with the spectra and retention times of authentic compounds reported previously in the literature for comparison.

The initial screening for antibacterial activity has shown that plants' chloroform extract was only inhibitory against P. aeruginosa and B. cereus at the highest concentration of 6900 µg/mL (Table 2). P. aeruginosa is responsible for different etiological processes in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients in hospitals, whereas B. cereus is an opportunistic pathogen [36, 37]. On the other hand, the analogue compound 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol showed broad spectrum activity against all bacteria tested (Table 3). Indeed, the MIC ranged from 215 to 431 µg/mL against K. pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing strains being also bactericidal at 431 µg/mL (Table 3). The carbapenems imipenem, meropenem, and ertapenem are often used as last therapeutic choices against gram-negative multidrug-resistant bacteria [38]. Moreover, these bacteria usually show resistance to aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones due to the presence of gene gnr and bla kpc [39]. Thus, the risk of nosocomial infections is higher for patients in hospital's intensive care units [40, 41].

Table 2.

Antibacterial activity of the chloroformextract of A. cearensis and the analogue 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol.

| Bacterial species | Chloroform extract | 2-Methoxy-4-methylphenol | Ciprofloxacin | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC* | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| µg/ mL | ||||||

| Salmonella enterica Typhimurium | — | — | 215 | 431 | <6.7 | <6.7 |

| Escherichia coli | — | — | 215 | 431 | <6.7 | <6.7 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | >6900 | — | 431 | >6900 | <6.7 | <6.7 |

| Bacillus cereus | >6900 | — | 431 | 3450 | <6.7 | 107 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | — | — | 215 | 862 | <6.7 | <6.7 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | — | — | 215 | 862 | <6.7 | <6.7 |

*MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; MBC: minimum bactericidal concentration.

Table 3.

Antibacterial activity of 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol against Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing strains.

| K. pneumonia strains | 2-Methoxy-4-methylphenol | Ciprofloxacin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC* | MBC | MIC | MBC | |

| (µg/mL) | ||||

| KPC 201 | 215 | 431 | <6.7 | <6.7 |

| KPC 199 | 215 | 431 | <6.7 | <6.7 |

| KPC + | 215 | 431 | <6.7 | 215 |

| KPC 278 | 215 | 431 | <6.7 | 431 |

*MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; MBC: minimum bactericidal concentration.

According to PubChem Compound Database, 4-methoxy-3-methylphenol is also known as 14786-82-4, AG-D-93185, NSC168522, AC1L6RKC, SureCN263095, and 4-methoxy-3-methylphenol [42]. Although anticancer assays were previously carried out with the compound, it was reported to be inactive against tumor model L1210 leukemia in mice [42]. While we were not aware of previous antimicrobial studies conducted with 4-methoxy-3-methylphenol, we hypothesize that the action mechanism of the molecule against bacteria is possibly due to 3-methylphenol compound (m-cresol) well known as an oxidizing agent [43]. Yet, m-cresol is a methyl derivative of phenol that has been used as precursor of amylmetacresol present in commercial antiseptic formulation.

The array of chemical compounds in A. cearensis extracts varies despite the type of solvent used (Table 4). Accordingly, we have shown that chloroform extracts of A. cearensis are good sources of methoxy-methylphenol compounds with antibacterial activity against several bacterial species and clinical isolates of multidrug-resistant K. pneumonia. Thus, the plants' chloroform extract could be exploited as a source of antiseptics or biocides against drug-resistant bacteria from different species.

Table 4.

Phytochemicals reported in extracts of A. cearensis.

| Part used | Solvent | Secondary metabolites | Antibacterial activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem bark | Ethanol | Not reported | Staphylococcus epidermidis | [9] |

| Stem bark | Ethanol | Not reported | Cocci strains, Enterobacteria, non-fermenting bacteria | [10] |

| Stem bark and leaves | Ethanol | Anthocyanins, anthocyanidins, flavones, chalcones, aurones, leucoanthocyanidins | Not reported | [11, 13] |

| Seeds | Butanol and hydroethanol | Flavonoids, proanthocyanidins, anthocyanins, carotenoids | Not reported | [26] |

| Aerial parts and xylopodium | Ethanol | Protocatechuic acid, vanillic acid, coumarin, amburoside | Not reported | [27] |

| Resin | Methanol and chloroform | Chalcone, 2′,4,4′-trihydroxy chalcone (isoliquiritigenin a) (1), 2′,4′, dihydroxy-3′,4′-methoxychalcone (2), 7,8,3′,4′-tetramethoxy isoflavone, 2′,4,4′-trihydroxy (isoliquiritigenin) (1); 2′,4′,dihydroxy-3′,4′-methoxy (2),7,8,3′,4′-tetramethoxy isoflavone |

Not reported | [28] |

| Stem bark | Ethanol | Coumarin and phenolic compounds (isokaempferide and amburoside) | Not reported | [29] |

| Wood powder | Hydroethanol | 1-Dodecanol; 2-ethyl-hexane acid; dihydrocoumarin; coumarin (1,2- benzopyrone) | Not reported | [30] |

| Stem bark | Ethanol | Isoflavonoid (afromorsin) | Not reported | [31] |

| Stem bark | Hexane and chloroform | Cumarina Coumarin (1,2 - benzopirona) (1,2-benzopyrone) | Not reported | [32] |

| Trunk bark | Ethanol | Coumarin and vanillic acid | Not reported | [33] |

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Suzene Izidio da Silva for botanical identification and Dr. Marcia Moraes for providing the Klebsiella strains used in the present study.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.de Albuquerque UP, de Oliveira RF. Is the use-impact on native caatinga species in Brazil reduced by the high species richness of medicinal plants? Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;113(1):156–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bieski IGC, Rios Santos F, De Oliveira RM, et al. Ethnopharmacology of medicinal plants of the pantanal region (Mato Grosso, Brazil) Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012:36 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/272749.272749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conceição GM, Ruggieri AC, Araújo MFV, et al. Medicinal plants of the Cerrado: sales, use and indication provided by the healers and sellers. Scientia Plena. 2011;7:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoult JRS, Payá M. Pharmacological and biochemical actions of simple coumarins: natural products with therapeutic potential. General Pharmacology. 1996;27(4):713–722. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)02112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leal LKAM, Matos ME, Matos FJA, Ribeiro RA, Ferreira FV, Viana GSB. Antinociceptive and antiedematogenic effects of the hydroalcoholic extract and coumarin from Torresea cearensis Fr. All. Phytomedicine. 1997;4(3):221–227. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(97)80071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leal LKAM, Ferreira AAG, Bezerra GA, Matos FJA, Viana GSB. Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator activities of Brazilian medicinal plants containing coumarin: a comparative study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2000;70(2):151–159. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leal LKAM, Oliveira FG, Fontenele JB, Ferreira MAD, Viana GSB. Toxicological study of the hydroalcoholic extract from Amburana cearensis in rats. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2003;41(4):308–314. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canuto KM, Silveira ER, Bezerra AME. Phytochemical analysis of cultivated specimens of cumaru (Amburana cearensis A. C. Smith) Quimica Nova. 2010;33(3):662–666. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonçalves AL. Study of antimicrobial activity of some indigenous medicinal trees with potential for conservation/ restoration of tropical forests [Ph.D. thesis] São Paulo, Brasil: Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Paulista; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Sá MCA, Peixoto RM, Krewer CC, da Silva Almeida JRG, Vargas AC, da Costa MM. Antimicrobial activity of caatinga biome ethanolic plant extract against gram negative and positive bacteria. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Veterinária. 2011;18:62–66. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lima-Filho JV, Martins LV, Nascimento DCO, et al. Zoonotic potential of multidrug-resistant extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli obtained from healthy poultry carcasses in Salvador. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Disease. 2013;17:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cos P, Vlietinck AJ, Berghe DV, Maes L. Anti-infective potential of natural products: how to develop a stronger in vitro ‘proof-of-concept’. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2006;106(3):290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Souza LGPR. Ethnobotanical phytochemical studies and researches of the garden of medicinal plants [Ph.D. thesis] Paraíba, Brasil: Univ. Federal de Campina Grande; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batista JEC, Ferreira EL, Nascimento DCO, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and detection of the mecA gene besides enterotoxin-encoding genes among coagulase-negative Staphylococci isolated from clam meat of Anomalocardia brasiliana . Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2013;10(12):1044–1049. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2013.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antunes RMP, Lima EO, Pereira MSV, et al. Antimicrobial activity, “in vitro” and determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of phytochemicals and synthetic compounds against bacteria and yeast fungi. In: Auricchio MT, Bacchi EM, editors. Leaves of Eugenia Uniflora (Pitanga): Pharmacobotanical, Chemical and Pharmacological Properties. Vol. 62. 2003. pp. 55–61. (Revista do Instituto Adolfo Lutz). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Interaminense JA, Nascimento DCO, Ventura RF, et al. Recovery and screening for antibiotic susceptibility of potential bacterial pathogens from the oral cavity of shark species involved in attacks on humans in Recife, Brazil. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2010;59(8):941–947. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.020453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perumal SR, Manikandan J, Al Qahtani M. Evaluation of aromatic plants and compounds used to fight multidrug resistant infections. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:17 pages. doi: 10.1155/2013/525613.525613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Der Berg ME. Medicinal plants in the Amazon—contribution to systematic knowledge. Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. 1982:50–198. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walther-Rasmussen J, Høiby N. OXA-type carbapenemases. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2006;57(3):373–383. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams RP. Identification of Essential Oil Components By Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Carol Stream, Ill, USA: Allured Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang R, Yang L, Jia CC, Hong WZ, Chen G-X. High-level carbapenem resistance in a Citrobacter freundii clinical isolate is due to a combination of KPC-2 production and decreased porin expression. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2008;57(3):332–337. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47576-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva AB, Silva T, Franco ES, et al. Antibacterial activity, chemical composition, and cytotoxicity of leaf’s essential oil from Brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolius, Raddi) Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2010;41(1):158–163. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220100001000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lima-Filho JV, Cordeiro RA. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial and antifungal screening of natural plant products: prospective standardization of basic methods. In: Albuquerque UP, Cruz da Cunha LVF, Lucena RFP, et al., editors. Methods and Techniques in Ethnobiology and Ethnoecology. Springer Protocols Handbooks; 2014. pp. 275–291. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Den Dool H, Dec. Kratz P. A generalization of the retention index system including linear temperature programmed gas-liquid partition chromatography. Journal of Chromatography A. 1963;11:463–471. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)80947-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams RP. Identification of Essential Oil Components By Gas Chromatograpy/Mass Spectroscopy. Carol Stream, IIl, USA: USDA, Allured Publishing Corporation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rego NO, Jr., Fernandez LG, Castro RD, et al. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of crude extract of brushwood vegetable species. Brazilian Journal of Food Technology. 2011;14:50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canuto KM, Silveira ER, Bezerra AME, et al. Use of young plants of A. cearensis AC Smith: Alternatives for Preservation and Economic Exploitation and Economic exploitation of Species. Embrapa Semi-árido, Petrolina, Doc. 208, p. 24, 2008.

- 28.Bandeira PN, de Farias SS, Lemos TLG, et al. New derivatives of isoflavone and other flavonoids from the resin Amburana cearensis . Journal of the Brazilian Chemistry Society. 2011;22(2):372–375. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leal LKAM. Contribution to the validation of the medicinal use of Amburana cearensiis (Cumaru): pharmacological studies with isokaempferide and amburoside [Ph.D. thesis] Fortaleza, Brazil: Universidade Federal do Ceará; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leão MM. Influence of treatment chemical composition of wood amburana (Amburana cearensis), balm (Myroxylon balsamum) and carvalho (Quercus sp.) and the impact on the aroma of rum from a model solution [Ph.D. thesis] São Paulo, Brasil: Escola superior de Agricultura Luiz de Queiroz, Universidade de São Paulo; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopes AA. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capsules of standardized dry layer and the isoflavone afrormosina obtained from Amburana cearensis AC SMITH [Ph.D. thesis] Fortaleza, Brasil: Universidade Federal do Ceará; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marinho MDGV, De Brito AG, Carvalho KDA, et al. Amburana cearensis and coumarin immunomodulate the levels of antigen-specific antibodies in ovalbumin sensitized BALB/c mice. Acta Farmaceutica Bonaerense. 2004;23(1):47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leal LKAM, Pierdoná TM, Góes JGS, et al. A comparative chemical and pharmacological study of standardized extracts and vanillic acid from wild and cultivated Amburana cearensis A.C. Smith. Phytomedicine. 2011;18(2-3):230–233. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koneman EW, Allen SD, Janda WM, et al. Microbiological Diagnosis: Text and Color Atlas. 5th edition. Rio de Janeiro, Brasil: MEDSI; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Negri G, Oliveira AFM, Salatino MLF, Salatino A. Chemistry of the stem bark of Amburana cearensis (Allemão) (A.C.SM.) Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais. 2004;6(3):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Onguru P, Erbay A, Bodur H, et al. Imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: risk factors for nosocomial infections. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2008;23(6):982–987. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.6.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turnbull PCB, Jorgensen K, Kramer JM, Gilbert RJ, Parry JM. Severe clinical conditions associated with Bacillus cereus and the apparent involvement of exotoxins. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1979;32(3):289–293. doi: 10.1136/jcp.32.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodloff AC, Goldstein EJC, Torres A. Two decades of imipenem therapy. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2006;58(5):916–929. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chmelnitsky I, Navon-Venezia S, Strahilevitz J, Carmeli Y. Plasmid-mediated qnrB2 and carbapenemase gene bla KPC−2 carried on the same plasmid in carbapenem-resistant ciprofloxacin-susceptible Enterobacter cloacae isolates. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2008;52(8):2962–2965. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01341-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poh CL, Yap SC, Yeo M. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for differentiation of hospital isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae . Journal of Hospital Infection. 1993;24(2):123–128. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(93)90074-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ben-Hamouda T, Foulon T, Ben-Cheikh-Masmoudi A, Fendri C, Belhadj O, Ben-Mahrez K. Molecular epidemiology of an outbreak of multiresistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Tunisian neonatal ward. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2003;52(5):427–433. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.04981-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Center for Biotechnology Information. http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/summary/summary.cgi?cid=297394#x299.

- 43.Cooper EA. On the relationship of phenol and m-cresol to proteins: a contribution to our knowledge of the mechanism of disinfection. Biochemical Journal. 1912;6:362–387. doi: 10.1042/bj0060362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]