Abstract

In the last three decades since the discovery of p53, it has become increasingly apparent that p53 plays a very important role in tumor suppression. Previously, it was thought that the tumor suppressive functions lied solely in the canonical p53-mediated apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and senescence. However, more recent research has shown that anti-oncogenic activity of p53 can still occur in the absence of these downstream functions. These results suggest that more non-canonical roles of p53 may have a much larger impact on other p53-regulated programs then initially anticipated. Recently, the non-canonical activities of p53 such as cell metabolism, autophagy and necrosis have been the subject of intense study. p53 affects many aspects of cellular metabolism including catabolism, anabolism and reactive oxygen species levels. p53 has a dual role in autophagy regulation. Initiation of autophagy occurs through direct transcription of pro-autophagy genes and inhibition transpires through a transcription-independent mechanism. The role of p53 in these cellular processes is quite complex and evidence suggests that p53 can play both a pro- and anti-oncogenic role in these non-conical pathways. Despite of more than 60 000 publications on p53 in the literature, the mechanisms for p53-mediated tumor suppression apparently needs to be further elucidated.

Introduction

p53 is best known as the ‘guardian of the genome’, due to its pivotal role as a tumor suppressor. Mutations in p53 or disruptions in its upstream or downstream regulatory network have been identified in over 50% of human cancers (1). As such, p53 is a very attractive candidate to target for the development of cancer therapies. However, it is essential to understand the implications of affecting such a critical gene before any treatment method can be developed. The p53 protein is a critical signaling molecule that is capable of converting upstream stress signals into diverse downstream responses, including cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence and apoptosis (2). Loss of proper p53 function often leads to tumorigenesis as seen in p53− /− and other mouse models (3–6). Classically, it was accepted that the ability of p53 to prevent tumor formation was due to transactivation of genes involved in apoptosis (PUMA and NOXA), transient cell cycle arrest (p21 and Ccng1) and a permanent cell cycle arrest termed senescence (p21 and E2F7) (7–10). However, there is mounting evidence that suggests that tumor suppressive effects of p53 extend beyond its ability to arrest the cell cycle or induce programmed cell death.

In 1995, Deng et al. (11) demonstrated that mice lacking p21 CIP1/WAF1 but retaining wild-type p53 function, unlike p53− /− mice, fail to form malignant tumors. These results suggest that cell cycle arrest at the G1/S checkpoint is not the sole downstream pathway by which p53 mediates its anti-oncogenic activity. Moreover, characterization of Puma− /− and Noxa− /− mice found that in the absence of apoptosis, the mice fail to develop tumors (12,13), implying that both cell cycle arrest and apoptosis are not essential for p53-mediated tumor suppression. In 2011, Brady et al. (14) characterized knock-in mouse models containing mutations in one or both of the transactivation domains (TAD) of p53 (p5325,26/25,26, p5353,54/53,54 and p5325,26,53,54/25,26,53,54). These p53 mutants contain amino acid substitutions in the first TAD (p5325,26/25,26), the second TAD (p5353,54/53,54) or both TADs (p5325,26,53,54/25,26,53,54) of the p53 protein abrogating transactivation of many p53 target genes. Despite failure to induce cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in response to acute DNA damage, p5325,26/25,26 still retains its tumor suppressive functions (14). Moreover, under oncogenic stress, the single TAD mutants are still able to prevent tumorigenesis, whereas inactivation of both TADs completely abrogates the transactivation capacity of this protein, and therefore, loses tumor suppressive function. It is important to note that p5325,26/25,26 and p5353,54/53,54 are still capable of driving senescence. These results suggest that transactivation of all p53 downstream targets is unnecessary for tumor prevention; however, transactivation of a small subset of genes is indispensable for tumor suppression function (14). Additionally, Li et al. generated a p53 separation-of-function mutant (p533KR/3KR), which contains three lysine-to-arginine substitutions within the p53 DNA-binding domain. This mutant lacks the ability to induce apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and senescence. They demonstrated that in the absence of these p53-mediated functions, p533KR/3KR mice fail to form spontaneous tumors that are characteristic of p53− /− mice. Furthermore, certain metabolic genes were shown to be upregulated in response to cellular stress in p533KR/3KR mutants suggesting a role for more unconventional p53 targets in its antitumorigenic function (15). To further support this notion, triple knockout mice lacking Puma, Noxa and p21 expression showed no inclination toward tumor formation (16). Collectively, these results beg the question ‘how is p53 exerting its tumor suppressor function?’ Recent research has begun to highlight other areas of p53 biology that may be responsible for its tumor suppressive function. This review will focus on the role of p53 in metabolism, autophagy and necrosis, and how they may contribute to its role as a tumor suppressor gene.

p53 and cellular metabolism

Cellular metabolism refers to the set of enzymatically catalyzed reactions within a cell that are essential for living organisms to survive and propagate. These reactions are split up into different metabolic pathways. Glycolysis is a process by which glucose is converted to pyruvate to form two molecules of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) per glucose and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. Alternatively, intermediate products of glucose metabolism can be shunted into the pentose phosphate pathway—a source of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate that is critical for lipid synthesis and antioxidant functions (17). Under normal aerobic conditions, the pyruvate generated during glycolysis will be delivered to the mitochondria where it is converted into acetyl-CoA before entering the Krebs cycle. The electron donors formed in the Krebs cycle are used in ATP generation by the oxidative phosphorylation pathway (17). Oxidative phosphorylation produces ATP via a series of redox reactions carried out by proteins located in the inner membrane wall of a the mitochondria. Although this process is essential to cellular metabolism, it forms reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, leading to the production of free radicals and subsequent cellular damage (17). Under homeostatic conditions, ROS are constantly produced and eliminated and are even required to drive certain cellular pathways. Conversely, under oxidative stress, excess ROS can damage various cellular components leading to lesions and perhaps carcinogenesis (17).

Otto Warburg was among the first to note altered cellular metabolism in cancer (18). Research focusing on mutations in several metabolic enzymes has suggested that altered cellular metabolism is sufficient to initiate tumorigenesis (18). Cancer cells often have increased glycolytic activity and reduced mitochondrial respiration, emphasizing adaptation from normoxic to hypoxic conditions as a critical switch in tumor progression (19). Thus, controlling aberrant cellular metabolism could feasibly prevent or delay tumorigenesis. Recent studies have shown that p53 is a master regulator for several metabolic genes, including glucose transporters 1 and 4 (GLUT1 and GLUT4), TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR), synthesis of cytochrome c oxidase 2 (SCO2) and glutaminase 2 (Gls2) (20–24). Interestingly, p53 null mice display a reduced level of endurance during physical exercise (21). This is consistent with data showing that loss of p53 reduces oxygen use and lowers the level of mitochondrial respiration, suggesting that genetic alterations in p53 or other members of the p53 pathway could contribute to the Warburg effect in tumors (21).

Glucose transporters 1 and 4

Tumorigenesis is characterized by an increase in glucose metabolism and consequently glucose uptake. Thus, the GLUTs that mediate glucose uptake in eukaryotic cells are potential candidates for regulation by oncogenes and tumor suppressors (25). GLUT1 is the major isoform found in most cells, whereas the other GLUT receptors are expressed in a more tissue-specific manner (25). GLUT1, as well as GLUT4 (expressed in mostly insulin-responsive tissue), is overexpressed in several different kinds of cancer, and in many cases, the expression level of GLUT1 is directly correlated with poor patient prognosis. GLUT4 overexpression is not as prevalent as GLUT1 overexpression but is still associated with a small subset of cancers, including many gastric carcinomas. Not only can GLUT expression be promoted by oncogenes as evidenced by work done on Ras and Src activation of GLUT isoforms but p53 also plays a role in suppressing their expression (25). Schwartzenberg et al. demonstrated that p53 has direct transcriptional repression activity on both GLUT1 and GLUT4 genes, although inhibition of GLUT4 transcription is more significant than transcriptional repression of GLUT1. One potential explanation for this is that GLUT4 is both tissue specific and insulin sensitive and p53 has been implicated, insulin signaling (25).

TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator

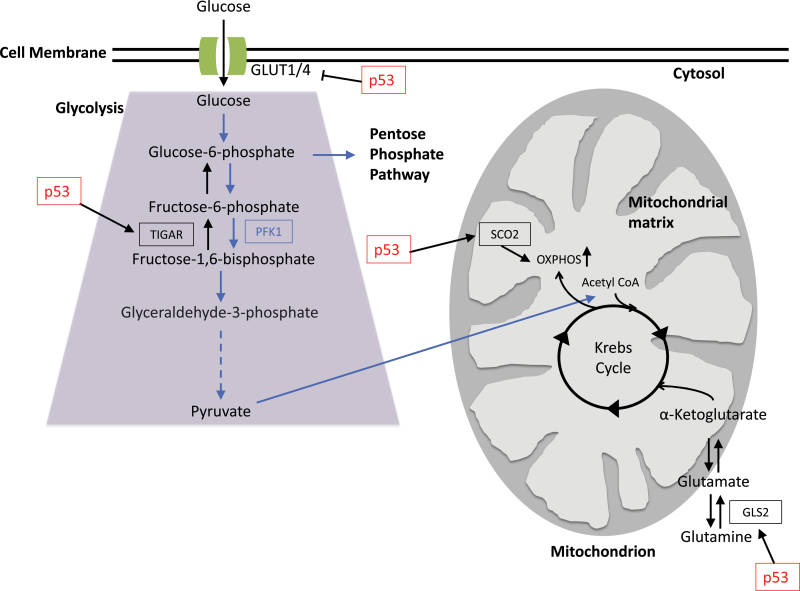

In 2006, Bensaad et al. (20) identified a novel p53 target gene called TIGAR that functions to regulate glycolysis and protect against oxidative stress. TIGAR has functional homology to the bisphosphatase domain of PFK-2 (6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase), which degrades fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (Fru-2,6-P2). Decreases in Fru-2,6-P2 favor the formation of fructose-6-phosphate, and thereby blocking glycolysis and directing this pathway into the pentose phosphate shunt to produce nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (Figure 1). Like PFK-2/FBPase-2, TIGAR is also capable of decreasing Fru-2,6-P2, and thus, promoting the shift from glycolysis to the pentose phosphate pathway. Ultimately, this results in the generation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate and nucleotides while increasing glutathione production, resulting in a reduction of cellular ROS levels (26). Therefore, TIGAR expression can protect cells from damage caused by ROS (20). Other models propose that cells with an increased shift toward the pentose phosphate shunt may be more effective at DNA repair possibly through the decreased oxidation of DNA (27,28).

Fig. 1.

p53 effects multiple areas of cellular metabolism. p53 can repress the transcription of glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT4. TIGAR is upregulated by p53 to suppress glycolysis and divert the pathway into the pentose phosphate pathway. Not only does p53 effect glucose metabolism but also plays a role in mitochondrial respiration and ATP production via the upregulation of SCO2 and GLS2. SCO2 is essential for mediating the formation and stabilization of the COX complex and thus critical for oxidative phosphorylation. GLS2 is a protein that catalyzes glutamine into glutamate. Glutamate can then be converted to α-ketogluterate, a key component in the Krebs cycle.

TIGAR falls into a group of proteins that are activated under low stress conditions and potentially have antitumorigenic effects (24). TIGAR was also identified by Li et al. (15) through quantitative reverse transcription–PCR as one of the metabolic genes still active in the p533KR/3KR mutant mice, suggesting that it may be contributing to p53 anti-oncogenic function. Interestingly, an association was made between high expression of p53 and low TIGAR expression in human breast cancer tissue (24). It is tempting to speculate that re-introduction of TIGAR into breast cancer may be an effective therapy. As mentioned above, TIGAR reduces the rate of glycolysis, and therefore lower TIGAR levels could be beneficial in malignant cells as increased glycolytic rates are associated with tumorigenesis (17,24).

Recently, a TIGAR knockout mouse model was developed to further understand the function of TIGAR. TIGAR-deficient mice showed defects in ROS maintenance and cellular proliferation following acute damage in the small intestine. It has also demonstrated that deregulation of TIGAR expression in colon cancer contributes to rapid cell proliferation and TIGAR expression is upregulated in both primary and metastatic colon tumors (29). Interestingly, TIGAR expression in these colon tumor samples did not correlate with p53 expression, clearly demonstrating that TIGAR expression can become uncoupled from p53 expression to promote tumor formation. As a p53 responsive gene, TIGAR becomes elevated in response to mild forms of cellular stress to regulate cellular ROS levels and prevent genotoxic stress caused by elevated ROS (20). However, the results shown by Cheung et al. (29) suggest a pro-oncogenic role for TIGAR as well.

Synthesis of cytochrome c oxidase 2

Identified as a p53 target in 2006, SCO2 is essential for mediating the assembly of the cytochrome c oxidase (COX) complex, which is critical for oxidative phosphorylation. Inactivation of the COX complex leads to aerobic respiratory failure (21). Mitochondrial respiration is responsible for consuming the majority of intracellular oxygen. Under normal cellular conditions, glycolysis is often blocked by the presence of oxygen. This allows for the mitochondria to undergo the Krebs cycle and oxidative phosphorylation to transform pyruvate into CO2 and H2O, while producing ATP. However, in cancer cells, which are often under hypoxic conditions, mitochondrial respiration is reduced as a result of altered expression of COX complex subunits (21). It is tempting to speculate that SCO2 may play an antitumorigenic role in carcinogenesis by regulating the flux between glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration.

SCO2 has been shown to increase the rate of oxidative phosphorylation by stabilizing the COX17 subunit and promoting COX complex formation (21). One consequence of this is an increase in cellular ROS levels. In HCT116 p53-deficient cells, SCO2 protein and mRNA levels are decreased. Reduction of SCO2 results in decreased oxygen consumption and increased glycolysis compared with wild-type cells. Furthermore, knocking out one copy of the SCO2 gene, creating a SCO2+/− line, was sufficient to phenocopy the metabolic defects of p53− /− cell lines (21). Additionally, low SCO2-expressing breast cancer patients showed a significantly poorer prognosis compared with patients expressing high levels of SCO2, further suggesting that the regulation of metabolic pathways by p53 plays a role in tumorigenesis (24). Madan et al. (23) recently reported a novel function of SCO2 that could explain why downregulation of this gene is beneficial to cancer cells. The study reported an alternate p53-mediated apoptotic pathway that is stimulated through SCO2 expression. SCO2 expression interrupts the interaction between apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK-1) and its cellular inhibitor thioredoxin via phosphorylation of ASK-1 at Thr(845). Dissociation of ASK-1 from thioredoxin activates the ASK-1 kinase pathway and induces apoptosis. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that downregulation of SCO2 expression promotes survival and propagation of malignant cells by decreasing oxygen consumption, increasing glycolysis. Low SCO2 expression also prevents the formation of ROS and therefore preventing ROS-dependent apoptosis and promoting cell survival (23).

Glutaminase 2

Gls2 is a mitochondrial glutaminase that modulates mitochondrial respiration and ATP generation. (21,22). It was identified as a transcriptional target of p53 by Hu et al. (22) and is responsible for the catalysis of glutamine to glutamate. Glutamate can then be converted to α-ketogluterate, which feeds into the trichloroacetic acid cycle providing an alternative pathway for energy production in the absence of glucose (17). Glutamate is also a precursor for glutathione synthesis; thus, GLS2 expression prevents oxidative stress caused by ROS, which further suggests that p53 plays a critical role in antioxidant defense. Data also suggest that GLS2 has antitumorigenic capabilities. Hu et al. (22) showed that GLS2 levels were greatly reduced in hepatocellular carcinomas and overexpression of GLS2 in these cell lines significantly reduced tumor cell colony formation. Additionally, others have reported a loss of GLS2 expression in brain tumors, and upon restoration of GLS2 expression, tumor cell proliferation and migration was inhibited (30). This is of particular interest because GLS1, a kidney-specific isoform of GLS2, has been shown to be under the control of the proto-oncogene, MYC, suggesting that under malignant conditions, these isoforms have opposing roles in tumorigenesis (31). There are a couple possible reasons for this differential regulation: (i) the two isoforms are expressed in a cell-type-specific manner and, thus, regulation of expression may be context and cell-type specific or (ii) differential expression of the two isoforms could have some functional redundancy to prevent disruption of normal glutaminolysis and ultimately prevent tumor formation (22,31). Further research is still needed to elucidate the exact mechanisms by which GLS1 and GLS2 impact tumor formation.

Autophagy and p53

Autophagy, which literally translates as self-eating, describes a process by which cells degrade components within their cytoplasm (32). There are three main types of autophagy: macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy. Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) has the most evidence in support of its role in tumor biology (33). Autophagy begins with the formation of an autophagosome, a double-membraned organelle that engulfs cytoplasm as it is formed. This can be done in a selective or unselective manner and is mediated by autophagy adaptors that link the growing autophagosome membrane to its target (33). Upon receiving signals from other endocytic vesicles, the autophagosome fuses to a lysosome—an organelle containing degradative enzymes—and its contents are degraded. Under homeostatic conditions, autophagy functions as a cellular quality control mechanism that removes damaged organelles or protein aggregates and degrades them (32,34,35). Autophagy is also an essential process during cellular starvation because it is instrumental in the formation of catabolites via the breakdown of metabolites into the cytoplasm, releasing the building blocks the cell needs to proliferate despite nutrient deprivation (33).

Autophagy has attracted immense interest in the field of tumor biology. Core autophagy regulators such as Beclin1 and UVRAG are often deleted or mutated in human cancers and studies in mouse models have underscored their importance in tumor prevention (36). Additionally, there are a number of proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes that directly influence the autophagic pathway, highlighting the importance of this cellular pathway in tumorigenesis (36). However, through emerging evidence, it has become apparent that the potential role for autophagy in tumorigenesis is very complex. Not only does autophagy have both tumor suppressing and tumor promoting functions (33) but regulation of autophagy via p53 has been shown to be both transcription dependent and transcription independent (37).

Transcription-dependent regulation

Damaged regulated autophagy mediator.

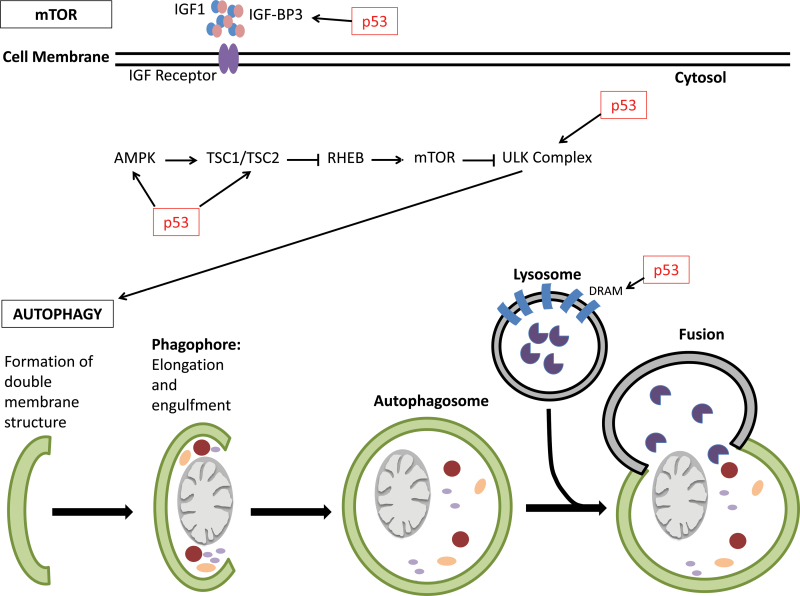

In 2006, damaged regulated autophagy mediator (DRAM) was identified via microarray analysis as a direct target of p53 and linked p53 function to autophagy (36,38). Crighton et al. (38) showed that in the absence of DRAM and p53, there is an accumulation of autophagasomes suggesting that p53 is necessary for successful autophagy in a DRAM-dependent manner (Figure 2). DRAM is a transmembrane protein that is localized to the lysosomal membrane and is upregulated in a DNA damage response-dependent manner (36,38). This suggests that DRAM is a selective pro-autophagic target that promotes autophagy in response to certain cellular signals. Not only is DRAM critical for p53-mediated autophagy but it also has been implicated as a critical component of p53-mediated apoptosis. Although DRAM expression alone is not sufficient to induce an apoptotic response, it is tempting to speculate that concomitant activation of DRAM and other pro-apoptotic genes promote crosstalk between the autophagic and apoptotic pathways to promote apoptosis (38). Crighton et al. (38) also demonstrated a downregulation of DRAM in squamous cell tumors, which may occur preferentially in tumors that are unable to directly inactivate p53, suggesting a potential role for DRAM as a tumor suppressor. Due to the role of DRAM in p53-medaited apoptosis, these results make DRAM an attractive target for future studies in cancer therapeutics.

Fig. 2.

p53 influences autophagy. p53 has a direct role in influencing autophagy directly and indirectly. p53 can directly upregulates pro-autophagic genes such as DRAM, which is involved in autophagy initiation. p53 also directly transcribes several genes involved in the IGF-1-AKT-mTOR pathways such as β1 and β2 subunits of AMPK, TSC2 and IGF-BP3. Upregulation of these genes leads to the eventual inhibition of mTOR and thus activation of autophagy. p53 also upregulates the Ulk1 kinase, which is involved in the initiation of autophagy.

IGF-1-AKT-mTOR pathways.

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) itself can be thought of as a switch. Under homeostatic conditions, mTOR can promote the translation of genes involved in energy production, whereas during starvation, mTOR can promote the degradation of organelles into catabolites for cellular maintenance under adverse conditions (39). p53 has been shown to affect autophagy through inhibition of mTOR pathway leading to activation of autophagy (39). Prior to this study, it had been shown that p53 stress response activates autophagy by ablating mTOR-dependent S6 kinase (40). Since then Feng et al. (39,40) determined that p53 is capable of upregulating the β1 and β2 subunits of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), TSC2 and IGF-BP3, demonstrating mechanistically how p53 is upregulating autophagy via the mTOR pathway (Figure 2). AMPK, a protein involved in detecting cellular glucose levels, signals TSC1/TSC2 complex, which ultimately leads to the inhibition of mTOR and thus activation of autophagy. The insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1)/Akt pathway coregulates the mTOR pathway by inhibiting TSC2 via AKT-1-dependent phosphorylation, and thereby inhibiting mTOR and activating autophagy (40). IGF-BP3 is a secretory protein involved in this pathway. It is responsible for binding and sequestering IGF-1 thereby allowing IGF-1 to bind to its respective IGF receptor and inducing the signal cascade. It is important to note, however, that expression of these genes via p53 seems to be both cell-type and tissue specific (39). Additionally, there is evidence of p53-dependent upregulation of sestrins 1 and 2—AMPK activators (37). Interestingly, AMPK can directly phosphorylate p53 and promote cell cycle arrest, suggesting an additional crosstalk between autophagy and other p53-mediated pathways (37).

Additional genes involved in mediating cellular autophagy have been identified. Recently, both Ulk1 and ISG20L1 were determined to be direct transcriptional targets of p53 (41,42). Ulk1 is an evolutionarily conserved protein involved in autophagy initiation and is activated via direct phosphorylation of Ulk1 by AMPK, which directly links mTOR signaling to autophagy initiation (42,43). ISG20L1 is a modulator of autophagy that is upregulated in response to genotoxic stress (41). Broz et al. (44) identified additional p53-mediated autophagy genes, but further efforts are required to elucidate their potential role in p53 tumor suppression.

Transcription-independent regulation

Interestingly, although nuclear p53 seems to positively regulate autophagy in response to stress signals, cytosolic p53 seems to repress autophagy (45). Tasdemir et al. (46) showed that the abrogation of p53 in human, mouse and nematode cells induce autophagy. Although autophagy is normally regulated through the mTOR pathway, some recent studies have demonstrated that ROS contribute to this cellular response (47–49). It is through the regulation of ROS that p53 seems to mediate its anti-autophagic function (50). Cytosolic p53 is often found to be interacting with TIGAR and loss of TIGAR not only has the metabolic phenotypes discussed above but also increases the rate of autophagy (50). Changes in TIGAR expression did not alter the kinase activity of the S6 protein suggesting that the means by which it is regulating autophagy is through ROS levels not the mTOR pathway (50).

Necrosis and p53

Originally, necrosis was defined as an uncontrolled form of cell death that lacks the defining features of apoptosis and autophagy (51). However, it is becoming apparent that necrosis may not always be uncontrolled, but rather represents another programmed form of cell death (51). Necrotic cells have a characteristic morphology including cellular and organelle swelling, plasma membrane leakage, an increase in the number of small vacuoles, and mitochondrial distension (52). Recent research has started to tease out the molecular mechanism behind programmed necrosis. Several tumor necrosis factor-like cytokines have been identified as crucial regulators of necrosis. This initiates the formation of the ripoptisome. Inhibition of apoptosis allows RIPK1 to form a complex with RIPK3, also known as the necrosome. Clustering of multiple necrosomes into an amyloid structure in conjunction with recruitment of cofactors allows necrosis to occur. (52).

It has been hypothesized that the function of necrosis is to provide an alternative form of cellular death should apoptosis fail (53). As such it is likely to play a role in many human pathologies including tumorigenesis. However, the tumor suppressive function of necrosis is complex and may be context specific. Glioblastomas exhibit extensive amount of necrotic tissues regardless of tumor size (54). These necrotic tissues appear to be the result of programmed necrosis, which facilitates angiogenesis and tumor survival rather than preventing tumorigenesis (54). Thus, programmed necrosis and its role in tumorigenesis could be tissue specific. Further research needs to be done to further elucidate pro- or antitumorigenic effects of programmed necrosis. Additionally, both apoptosis and necrosis begin with the same signaling molecules, it is the downstream signaling that separates the apoptotic pathway from the necrotic pathway. Is it possible that these are two functionally redundant pathways in which necrosis is the cells last ditch effort to kill damaged cells or is apoptosis a means to prevent the damaging effects of necrosis?

The role of p53 in necrosis appears to be very complex. In 2009, it was proposed that p53 induces necrotic death via Capthepsin Q, a lysosomal protease, in response to ROS and DNA damage (55). However, this necrotic pathway seems to be separate from the RIPK1-dependent pathway, as necrostatin, a RIPK1 inhibitor, did not succeed in preventing DNA damage-induced necrotic death in Bax–Bak double knockout (apoptosis deficient) cells. However, retroviral knockdown of p53 and overexpression of a dominant negative mutant p53 did prevent initiation of necrotic program upon DNA damage, confirming that p53 may play an important role in RIP1K-independent programmed necrosis (55). More recently another role for p53 in the induction of necrosis has been discovered. Vaseva et al. (56) found that upon oxidative stress, p53 is translocated into the mitochondrial matrix and facilitates the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore by binding to CypD (permeability transition pore regulator), independent of its ability to open the Bax/Bak core of the mitochondrial outer membrane for apoptosis. Pore opening is the result of structural changes caused by p53-binding CypD. This p53–CypD complex is a potential therapeutic target to limit the amount of damage that can occur from products of necrosis.

Conclusions and perspectives

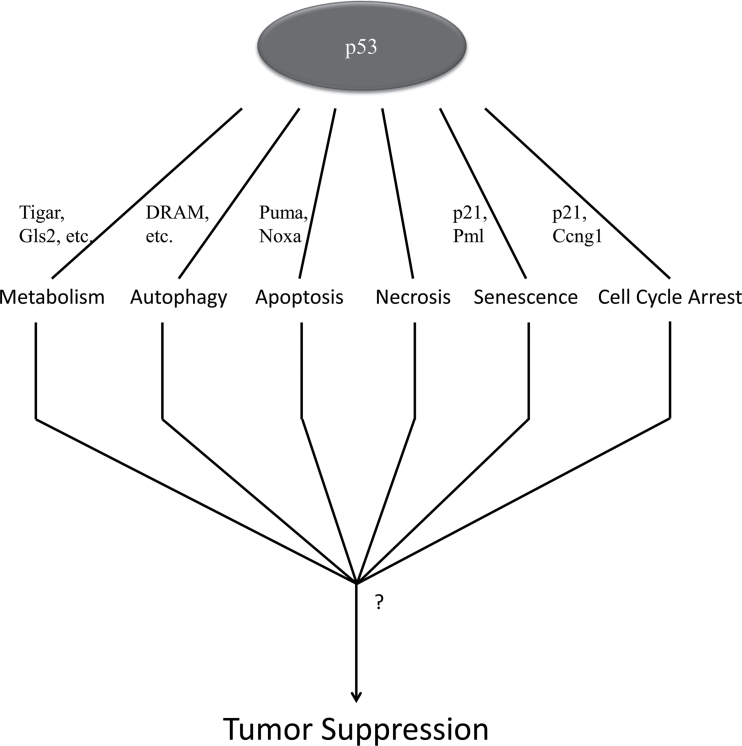

In the last several years, researchers have begun to focus on non-canonical p53-regulated functions as potential candidates for the tumor suppressive ability of p53. There are two prevailing theories on how p53 is exerting its anticarcinogenic activity: (i) the field has yet to uncover the underlying true tumor suppressive function of p53 or (ii) anti-oncogenic properties of p53 are the result of synergizing multiple downstream pathways of the p53 regulatory network (Figure 3). Brady et al. (14) demonstrated that p53 transactivation is necessary for its tumor suppressive function, but only when there are mutations in both of the N-terminal TADs. Mutations in only the first (p5325,26/25,26) or in only the second TAD (p5353,54/53, 54) failed to form tumors. However, when combined p5325,26,53,54/25,26,53,54 (transactivation dead) mutant mice formed tumors like p53− /− (3,14). Interestingly, although p5325,26/25,26 mutants fail to transactivate many downstream p53 targets, the results suggest that the small subset that are still transactivated are necessary for tumor prevention, suggesting there may be another downstream pathway by which tumor suppression function is being exerted.

Fig. 3.

Model. p53 regulates many cellular pathways, but the exact mechanistic role of p53 in tumor prevention has yet to be elucidated. There is increasing support for the idea that there may not be one downstream function of p53 that is solely responsible for preventing tumor formation, rather that there are multiple pathways that converge to exercise its tumor suppressive function.

On the other hand, the transformation from a benign cell to malignant cell may rely on more than one of p53’s downstream functions. A Recent study from Bensaad et al. also calls into question metabolism as the sole anti-oncogenic p53-regulated function (20). Although much research has supported the notion of proper metabolic regulation in tumor prevention (20–22), evidence of a pro-oncogenic role for TIGAR calls into question the extent to which metabolic regulation on its own can prevent tumor formation. Although not all tumor cells adhere strictly to the Warburg effect, it can be generally agreed upon that rapidly proliferating cells require an increased amount of energy and thus, an increased amount of glucose to generate ATP. Loss of p53 would generally favor glycolysis; however, a tumor’s entire metabolic profile could be the result of a combinatorial effect of many other factors. Autophagy is a cellular process that is critical for cell survival under metabolic stress (32,57). Although the role of autophagy in tumorigenesis is controversial, it can be agreed that the overlap between cellular metabolism and autophagic function is extensive. In addition to metabolism, some data show that autophagy is necessary for fully functional apoptosis as well. Although it was shown that DRAM alone could not induce an apoptotic response, it is critical for apoptotic response (38). Crighton et al. (38) presented a model in which concomitant expression of DRAM and several pro-apoptotic genes work together to promote a full cell death response. Therefore, it suggests that proper maintenance of multiple pathways simultaneously may confer tumor suppression.

Funding

National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award (5RO1 CA166294, PO1CA080058 to W.G.).

Acknowledgements

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest Statement: None declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- ASK-1

apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- COX

cytochrome c oxidase

- DRAM

damaged regulated autophagy mediator

- GLS2

glutaminase 2

- GLUT

glucose transporter

- IGF-1

insulin-like growth factor 1

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SCO2

synthesis of cytochrome c oxidase 2

- TAD

transactivation domain

- TIGAR

TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator.

References

- 1. Hainaut P., et al. (2000). p53 and human cancer: the first ten thousand mutations. Adv. Cancer Res., 77, 81–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lane D.P. (1992). Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature, 358, 15–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kemp C.J., et al. (1994). p53-deficient mice are extremely susceptible to radiation-induced tumorigenesis. Nat. Genet., 8, 66–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donehower L.A., et al. (1992). Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature, 356, 215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Attardi L.D., et al. (2005). Probing p53 biological functions through the use of genetically engineered mouse models. Mutat. Res., 576, 4–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jackson J.G., et al. (2013). The mutant p53 mouse as a pre-clinical model. Oncogene, 32, 4325–4330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. el-Deiry W.S., et al. (1993). WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell, 75, 817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. el-Deiry W.S., et al. (1994). WAF1/CIP1 is induced in p53-mediated G1 arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res., 54, 1169–1174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakano K., et al. (2001). PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol. Cell, 7, 683–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rufini A., et al. (2013). Senescence and aging: the critical roles of p53. Oncogene, 32, 5129–5143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deng C., et al. (1995). Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell, 82, 675–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Villunger A., et al. (2003). p53- and drug-induced apoptotic responses mediated by BH3-only proteins puma and noxa. Science, 302, 1036–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Michalak E.M., et al. (2008). In several cell types tumour suppressor p53 induces apoptosis largely via Puma but Noxa can contribute. Cell Death Differ., 15, 1019–1029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brady C.A., et al. (2011). Distinct p53 transcriptional programs dictate acute DNA-damage responses and tumor suppression. Cell, 145, 571–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li T., et al. (2012). Tumor suppression in the absence of p53-mediated cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence. Cell, 149, 1269–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Valente L.J., et al. (2013). p53 efficiently suppresses tumor development in the complete absence of its cell-cycle inhibitory and proapoptotic effectors p21, Puma, and Noxa. Cell Rep., 3, 1339–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maddocks O.D., et al. (2011). Metabolic regulation by p53. J. Mol. Med. (Berl), 89, 237–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu W., et al. (2013). Metabolic changes in cancer: beyond the Warburg effect. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai), 45, 18–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dang C.V., et al. (1999). Oncogenic alterations of metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci., 24, 68–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bensaad K., et al. (2006). TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell, 126, 107–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matoba S., et al. (2006). p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science, 312, 1650–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hu W., et al. (2010). Glutaminase 2, a novel p53 target gene regulating energy metabolism and antioxidant function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 107, 7455–7460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Madan E., et al. (2013). SCO2 induces p53-mediated apoptosis by Thr845 phosphorylation of ASK-1 and dissociation of the ASK-1-Trx complex. Mol. Cell. Biol., 33, 1285–1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Won K.Y., et al. (2012). Regulatory role of p53 in cancer metabolism via SCO2 and TIGAR in human breast cancer. Hum. Pathol., 43, 221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schwartzenberg-Bar-Yoseph F., et al. (2004). The tumor suppressor p53 down-regulates glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT4 gene expression. Cancer Res., 64, 2627–2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCarthy N. (2013). Metabolism: a TIGAR tale. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 13, 522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sablina A.A., et al. (2005). The antioxidant function of the p53 tumor suppressor. Nat. Med., 11, 1306–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang Y.M., et al. (2003). The DNA excision repair system of the highly radioresistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans is facilitated by the pentose phosphate pathway. Mol. Microbiol., 48, 1317–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cheung E.C., et al. (2013). TIGAR is required for efficient intestinal regeneration and tumorigenesis. Dev. Cell, 25, 463–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Szeliga M., et al. (2009). Transfection with liver-type glutaminase cDNA alters gene expression and reduces survival, migration and proliferation of T98G glioma cells. Glia, 57, 1014–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gao P., et al. (2009). c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature, 458, 762–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kroemer G., et al. (2010). Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol. Cell, 40, 280–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lorin S., et al. (2013). Autophagy regulation and its role in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol., 23, 361–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mizushima N., et al. (2011). Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell, 147, 728–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ravikumar B., et al. (2010). Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev., 90, 1383–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crighton D., et al. (2007). DRAM links autophagy to p53 and programmed cell death. Autophagy, 3, 72–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maiuri M.C., et al. (2010). Autophagy regulation by p53. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 22, 181–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Crighton D., et al. (2006). DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell, 126, 121–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Feng Z., et al. (2007). The regulation of AMPK beta1, TSC2, and PTEN expression by p53: stress, cell and tissue specificity, and the role of these gene products in modulating the IGF-1-AKT-mTOR pathways. Cancer Res., 67, 3043–3053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Feng Z., et al. (2005). The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 8204–8209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Eby K.G., et al. (2010). ISG20L1 is a p53 family target gene that modulates genotoxic stress-induced autophagy. Mol. Cancer, 9, 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gao W., et al. (2011). Upregulation of human autophagy-initiation kinase ULK1 by tumor suppressor p53 contributes to DNA-damage-induced cell death. Cell Death Differ., 18, 1598–1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim J., et al. (2011). AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol., 13, 132–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Broz D.K., et al. (2013). TRP53 activates a global autophagy program to promote tumor suppression. Autophagy, 9, 1440–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Criollo A., et al. (2009). DRAM: a phylogenetically ancient regulator of autophagy. Cell Cycle, 8, 2319–2320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tasdemir E., et al. (2008). Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nat. Cell Biol., 10, 676–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scherz-Shouval R., et al. (2007). Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J., 26, 1749–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chen Y., et al. (2008). Is mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species a trigger for autophagy? Autophagy, 4, 246–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen Y., et al. (2007). Mitochondrial electron-transport-chain inhibitors of complexes I and II induce autophagic cell death mediated by reactive oxygen species. J. Cell Sci., 120(Pt 23), 4155–4166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bensaad K., et al. (2009). Modulation of intracellular ROS levels by TIGAR controls autophagy. EMBO J., 28, 3015–3026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Golstein P., et al. (2007). Cell death by necrosis: towards a molecular definition. Trends Biochem. Sci., 32, 37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chan F.K. (2012). Fueling the flames: mammalian programmed necrosis in inflammatory diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol., 4, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Baumann K. (2012). Cell death: multitasking p53 promotes necrosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 13, 480–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jiang Y.G., et al. (2011). Necroptosis: a novel therapeutic target for glioblastoma. Med. Hypotheses, 76, 350–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tu H.C., et al. (2009). The p53-cathepsin axis cooperates with ROS to activate programmed necrotic death upon DNA damage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 1093–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vaseva A.V., et al. (2012). p53 opens the mitochondrial permeability transition pore to trigger necrosis. Cell, 149, 1536–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mizushima N. (2011). Autophagy in protein and organelle turnover. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol., 76, 397–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]