Abstract

Background:

This study was designed to assess the validity and reliability of the designed sexual, behavioral abstinence, and avoidance of high-risk situation questionnaire (SBAHAQ), with an aim to construct an appropriate development tool in the Iranian population.

Materials and Methods:

A descriptive–analytic study was conducted among female undergraduate students of Tehran University, who were selected through cluster random sampling. After reviewing the questionnaires and investigating face and content validity, internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed by Cronbach's alpha. Explanatory and confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using SPSS and AMOS 16 Software, respectively.

Results:

The sample consisted of 348 female university students with a mean age of 20.69 ± 1.63 years. The content validity ratio (CVR) coefficient was 0.85 and the reliability of each section of the questionnaire was as follows: Perceived benefit (PB; 0.87), behavioral intention (BI; 0.77), and self-efficacy (SE; 0.85) (Cronbach's alpha totally was 0.83). Explanatory factor analysis showed three factors, including SE, PB, and BI, with the total variance of 61% and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index of 88%. These factors were also confirmed by confirmatory factor analysis [adjusted goodness of fitness index (AGFI) = 0.939, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.039].

Conclusion:

This study showed the designed questionnaire provided adequate construct validity and reliability, and could be adequately used to measure sexual abstinence and avoidance of high-risk situations among female students.

Keywords: HIV, questionnaires, sexual abstinence, sexual behavior

INTRODUCTION

HIV/AIDS has been recognized as one of the most important public health problems in the recent past,[1,2] especially in Asian countries such as Malaysia,[3] China,[4] Thailand, and Iran.[5] According to the World Health Organization's (WHO's) report of HIV, Iran is categorized as one among the countries with gradually accumulating levels of infection.[6]

Preventing HIV infection is one of the top priorities in 2010 to lead a healthy life.[7] Three transmission ways have been identified for the disease: Sexual activity with an infected person, contact with infected blood through sharing injection needles, and mother-to-infant infection.[8] In order to prevent HIV transmission through sexual activities, which accounts for 85% of the disease, the three following options have been recommended: Abstinence, faithfulness, and condom use, among which the first one is the safest.

Due to the lack of global access to AIDS treatment and also based on the fact that HIV/AIDS transmission requires a behavioral process, behavioral change interventions are the best approach to prevent the spread of the disease.[9,10]

Since most health problems are closely related to human behavior, behavioral theories and models can provide insights into finding ways to prevent health problems such as HIV/AIDS.[11] Most of the studies conducted have been based on cognitive-behavioral, health belief models, and theories such as social cognitive theory (SCT) and theory of reasoned action (TRA).[12] Considering the results, and in order to increase the efficiency of the models, a selective mixture of aforementioned theories has been employed in the present study.

In his survey of AIDS-behavior change theories, Noar (2007) mentioned 13 theories used in the studies, including belief- and intervention-based, message-driven, and AIDS-related theories, and other common hygienic behavior changes.[13] Some researchers used a questionnaire based on behavior change theories or models such as motivation-behavioral skills model (IMB),[14] social cognitive theory (SCT),[15] and the theory of reasoned action (TRA).[16] Furthermore, the constructs such as knowledge,[17] attitude,[18] self-efficacy (SE),[19] behavioral intention (BI),[20] and high-risk sexual behavior[21] were used in some studies.

Like most Islamic countries, sexual affairs are considered as taboo in Iran.[22] Therefore, given the cultural differences between the Western countries and Iran and the sensitive nature of the disease, the HIV/AIDS behavior change questionnaires derived from the previous studies conducted in non-Islamic countries cannot be applied here. Although the validity and reliability of the questionnaire has been confirmed in a previous study,[23] this study was conducted only with male students. However, to our knowledge, no study has been carried out with female students so far. As females, in comparison with males, are physiologically more vulnerable to HIV/AIDS, female students were selected as the target group.[24] Considering the lack of appropriate tools and questionnaires, the study focused on designing and validating a culturally suitable sexual abstinence questionnaire among unmarried Iranian female students.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and study design

The study was cross-sectional in design and was conducted from February to June 2010. The study subjects were undergraduate female students studying at Tehran University. The criteria based on which the participants were selected were as follows: Age range of 15-25 years, single status, living alone, and residing in Tehran for at least 1 year at the time of the study. Those with physical disability and those reluctant to participate in the study were excluded.

For achieving an appropriate score maximum fitness and predicting the number of students, the participants were randomly selected from the three areas of humanities, engineering, and science at the University of Tehran. Then, the participants were selected through cluster systematic sampling (with each class as one cluster). For each question, a minimum of 10 samples were used according to Munro's method, and 348 female students were randomly selected to reach construct validity. Descriptive (mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach's alpha) and inductive statistics (exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis) functions of SPSS and AMOS ver. 16 were used to analyze the data.[25]

Instruments

A self-administered questionnaire was used which comprised the following four parts: Socio-demographic characteristics, SE regarding sexual abstinence, perceived benefits (PB) toward sexual abstinence, and Behavioral intention (BI). The demographic information included age, residency region, family income, parents’ education, and previous knowledge about HIV. There were four SE questions about individual restraint, avoidance of risky situations, and the behavioral skills of saying no. These questions were also designed according to the Iranian standardized general SE questionnaire.[26] For unifying the results and facilitating analysis, the questions were designed with five options ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. For each item, a typical 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) was used. The scale of PB consisted of six items measuring individual and social benefits of abstinence, risky behavior avoidance, negative answer to risky offers, and high-risk situation avoidance. Most questions were derived from the studies of Ghafari[23] and Miller et al.[27] Furthermore, one question with regard to the features of female students in the studied society was added to the aforementioned questions.

BI questions consisted of four items based on the dual behavior theory of Gibbons and Gerrard[28] and a domestic questionnaire designed by Ghaffari et al. These questions were about the BI of abstinence, a negative answer to risky advances, and avoidance of highly risky situations. Also, given the fact that the participants were young and prone to highly risky situations, one of the questions required them to give their own opinions about their willingness to avoid high-risk situations.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics, Cronbach's alpha, and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis functions of SPSS and AMOS ver. 16 were used to analyze the data.

Ethical issues

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University and ethical principles were adhered to throughout the study. After the researchers explained the purpose and procedures of the study to the participants, they consented to participate in the study.

RESULTS

In order to determine the face validity, the questionnaire was distributed to 30 students with similar characteristics. They were asked to pinpoint the weaknesses and ambiguities of the questionnaire, comment on its clarity, rationality, brevity, and appropriateness, and finally, improve it. Content validity ratio (CVR) was applied to assess the extent of experts comment upon the clarity, rationality, brevity and appropriateness of itThen, the questionnaire was given to 20 specialists in the fields of health education, nursing, medicine, and psychology to take the experts’ ideas into account. Content validity was assessed by each panel member with a 3-item Likert scale (the items were “necessary,” “useful but not necessary,” and “unnecessary”). In case an item was marked as “unnecessary,” the experts’ suggestions for modification or elimination were sought.

The CVR equal to 0.80 or above was considered satisfactory. The original questionnaire included 122 items in 11 separate parts. The number of questions was reduced to 50 after measuring the CVR.

Reliability

In order to verify the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha score was calculated. Cronbach's alpha or the internal consistency for PB, BI, and SE variables was found to be 0.87, 0.77, and 0.85, respectively. All these values indicate the desirable level of the scales.

In order to determine the construct validity of the questionnaire, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis was used. One way of investigating construct validity is by running a factor analysis for identifying clusters of questions related to the instruments. This method helps the researcher to determine whether the available tool measures one construct or several ones.[29]

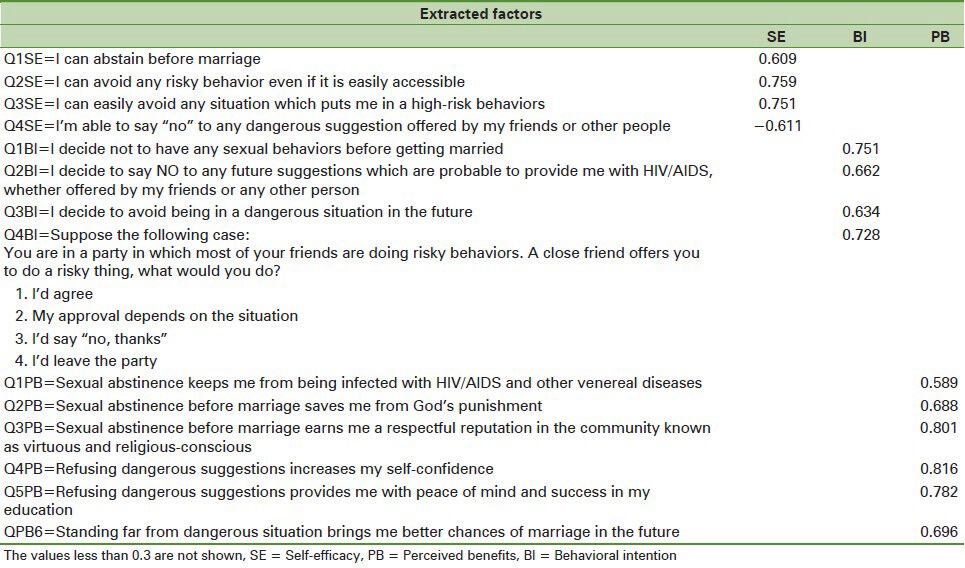

The exploratory factor analysis using principal components analysis with varimax rotation was used to determine compliance and naming of the extracted factors. Using all observations (N = 348), the factor analysis helped in identifying three decisive factors with a variance greater than 61% and 88% of Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO), both of which are appropriate indicators of factor analysis. After inserting three retention factors in the orthogonal varimax rotation, each of the factors was given a name and estimated using the probability method. Based on the loadings, and also the content of questions, the three factors were identified as SE, BI, and PB, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the data and loading factors. As presented in the chart, only the first three values have Eigen values more than one.[29] Six PB questions were omitted, and four SE and four BI questions were used in the model; at the final stage and after determining factor analysis, one SE question was deleted.

Table 1.

The results of the exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation

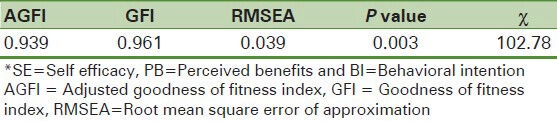

After running exploratory factor analysis, in order to confirm the supposed factor structure of the measure as well as the contribution of each question in measuring the components of self-efficacy, BI and PB were analyzed using Amos Software. Table 1 shows the most important parameters of the measuring components of the questionnaire. The most important fitness statistics is the Chi-square statistic. This shows the disparity between the observed and predicted measures (matrices). The insignificance of the statistics indicated the model's fitness with the data, but the pitfall of the statistics is that it is sensitive to the sample size, which means that with larger sample sizes, the possibility of the statistics being insignificant t decreases. Values less than 0.05 for the index root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), values above 0.9 for goodness of fitness index (GFI), and adjusted goodness of fitness index (AGFI) were used as the criteria for model compliance with the observed data [Table 3].[30]

Table 3.

Goodness fitness indexes of the sexual abstinence behavior of HIV/AIDS questionnaire

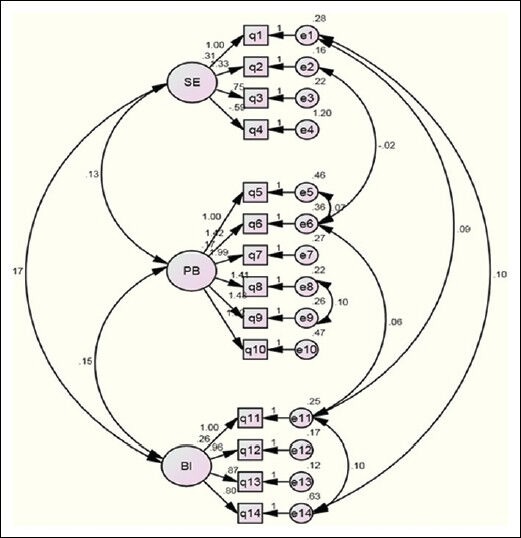

As it was stated, the model's of the goodness of fitness indexes are all acceptable. Therefore, the confirmatory factor analysis also approved the construct validity of the questionnaire [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Structural equation fitness to model

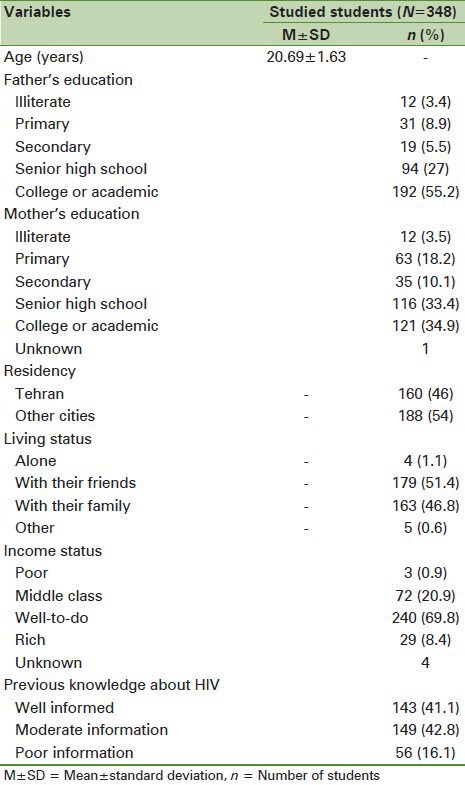

Demographic information

On the whole, 348 female students participated in the study. The mean age of the participants was 20.69 ± 1.63 years. Relevant demographic information is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The characteristics of the study sample

The average of CVR for the entire questionnaire was 0.85. The CVR for the subscales of PB, BI, and SE was calculated to be 0.83, 0.84, and 0.89, respectively. The time needed for completing the questionnaire was about 6 min.

DISCUSSION

Considering that there is lack of valid and reliable questionnaire on the behavioral changes of HIV/AIDS among Iranian females, we aimed to design an appropriate abstinence questionnaire and determine its validity and reliability.

Islamic religious beliefs play an important role in people's attitude to the disease.[31] This point has been taken into account to a lesser extent in the questionnaires developed in the Western countries. For example, some Iranians believe that avoiding unsafe sexual encounters would give them better chances of getting married in the future.

Other studies on the validity and reliability of domestic questionnaires have mainly investigated the knowledge of people and their behaviors and attitudes toward HIV, and reported the reliability of the scales.[32,33,34] For instance, in a study by Khatoni et al., face-to-face web-based training was employed to verify the content validity of nurses’ knowledge questionnaire by the experts, and also, the reliability of the questionnaire was confirmed through test–retest (0.9).[35] Furthermore, the Cronbach's alpha for the HIV/AIDS knowledge and attitude questionnaire developed by DiClemente et al. was reported to be 0.72.[36] In the study conducted by Nije-Carr on HIV/AIDS Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Patient Questionnaire (HAKABPQ), the internal consistency of the questions was shown to be higher than 0.7.[37] Also, the internal consistency of HIV-related knowledge, attitudes, and sexual risk-taking behaviors was reported to be 0.073 in the study by Ugarte et al.[38] In the study of Koopman et al. (1990), both the knowledge and belief instruments were indicated to have a high internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and successfully avoided ceiling effects.[39]

The highest reported figure was 0.96 for the validity of St Andrews Sexual Knowledge and Attitudes Instrument (SASKAI), which was conducted among female employees by Kappa test.[40] Of course, the high internal consistency is a result of high level of similarity among the questions. In the study of Hughes and Admiraal entitled “Systematic review of HIV/AIDS knowledge measures,” the results showed low reliability and a validity rate of HIV knowledge questionnaire. In general, the measuring instruments of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about HIV do not have a high level of internal consistency and have rarely been tested by factor analysis.[41]

Lux and Petoza designed a questionnaire based on which the Cronbach's alpha was estimated to be 0.64 and 0.79 for healthy sexual BI and SE of sexual discussion, respectively.[42] In another study conducted by Mahoney Thombs and Ford, the Cronbach's alpha SE subscale for using condoms was reported to be 0.91. Thus, all these questionnaires show their eligibility for application in related studies.[43] The scale of Mukoma et al.,[44] which was applied to evaluate school-based HIV/AIDS intervention in South African courtiers and Tanzania, reported a Cronbach's alpha of higher than 0.5. Regarding sexual behaviors, the Cronbach's alpha was lower than 0.5, based on which the author verified the utility of the scales. In a similar study conducted by Ghafari et al., the alpha values for a 10-scale instrument about HIV/AIDS prevention were 0.69, 0.78, and 0.74 for SE, PB, and BI, respectively, which were lower than those of the present instrument.[45]

It is worth noting that the alpha values between 0.8 and 0.9 show a high internal consistency and the alpha values of 0.7 and higher present a good internal stability.[46,47] In the present study, the Cronbach's alpha was between 0.77 and 0.87, indicating a good internal correlation of the instrument. Also, the reliability coefficient of the scale was approximately 0.85, which is satisfactory when seen in the light of the studies listed. There were three main measures of sexual behaviors: Abstinence, number of sexual partners, and condom use, which were measured[48] In some articles, the psychological measures of sexual abstinence instrument have not been mentioned.[49,50,51]

One of the strengths of the study was using different methods of testing reliability and validity and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. It should be noted that the questionnaire was optimal in terms of structure validity and scale clustering and the goodness of fitness indexes. Other researchers are suggested to work on the construction of theories of behavior change scale in Islamic contexts as well as to research into different groups of adolescents, youth, and occupations with the risk of HIV/AIDS infection.

CONCLUSION

This study have showed that the sexual behavioral abstinence, and avoidance of high-risk situation questionnaire (SBAHAQ) questionnaire can be used as a valid and reliable tool to measure abstinence and avoidance of high-risk situations regarding HIV/AIDS infection. However, it is recommended to test the validity of the tool in various communities such as students, scholars, etc.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Ms Marjan Sheikhi for translating and proofreading the article.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This research was financially supported by Tarbiat Modares University with Grant code TMU 129.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Acaroglu R. Knowledge and attitudes of mariners about AIDS in Turkey. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umeh CN, Essien EJ, Ezedinachi EN, Ross MW. Knowledge, beliefs and attitudes about HIV/AIDS-related issues, and the sources of knowledge among health care professionals in southern Nigeria. J R Soc Promot Health. 2008;128:233–9. doi: 10.1177/1466424008092793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong LP, Chin CK, Low WY, Jaafar N. HIV/AIDS-Related Knowledge Among Malaysian Young Adults: Findings From a Nationwide Survey. J Int AIDS Soc. 2008;10:148. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-10-6-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia Y, Lu F, Sun X, Vermund SH. Sources of data for improved surveillance of HIV/AIDS in China. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2007;38:1041–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youngkong S, Baltussen R, Tantivess S, Koolman X, Teerawattananon Y. Criteria for priority setting of HIV/AIDS interventions in Thailand: A discrete choice experiment. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:197. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheemeh PE, Montoya ID, Essien EJ, Ogungbade GO. HIV/AIDS in the Middle East: A guide to a proactive response. J R Soc Promot Health. 2006;126:165–71. doi: 10.1177/1466424006066280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Archibald C. Knowledge and attitudes toward HIV/AIDS and risky sexual behaviors among Caribbean African American female adolescents. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaitzow BH. Women prisoners and HIV/AIDS. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 1999;10:78–89. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyer CB, Barrett DC, Peterman TA, Bolan G. Sexually transmitted disease and HIV risk in heterosexual adults attending a public STD clinic: Evaluation of a randomized controlled behavioral risk-reduction intervention trial. AIDS. 1997;11:359–67. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199703110-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee TS, Fu LA, Fleming P. Using focus groups to investigate the educational needs of female injecting heroin users in Taiwan in relation to HIV/AIDS prevention. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:55–65. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sefa M, Marta M. Newton: Connecticut HIV Evaluation Bank; 2001. Designing effective interventions: Using science and experience In HIV. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basen-Engquist K, Coyle KK, Parcel GS, Kirby D, Banspach SW, Carvajal SC, et al. Schoolwide effects of a multicomponent HIV, STD, and pregnancy prevention program for high school students. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28:166–85. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noar SM. An interventionist's guide to AIDS behavioral theories. AIDS Care. 2007;19:392–402. doi: 10.1080/09540120600708469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, Misovich SJ. Information-motivation-behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychol. 2002;21:177–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heeren GA, Jemmott Iii JB, Ngwane Z, Mandeya A, Tyler JC. A Randomized controlled pilot study of an hiv risk-reduction intervention for Sub-Saharan African University Students. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:1105–15. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0129-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Randolph ME, Pinkerton SD, Somlai AM, Kelly JA, McAuliffe TL, Gibson RH, et al. Seriously mentally ill women's safer sex behaviors and the theory of reasoned action. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36:948–58. doi: 10.1177/1090198108324597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carey MP, Schroder KE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:172–82. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.2.172.23902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donenberg GR, Schwartz RM, Emerson E, Wilson HW, Bryant FB, Coleman G. Applying a cognitive-behavioral model of HIV risk to youths in psychiatric care. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17:200–16. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.4.200.66532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cecil H, Pinkerton SD. Reliability and validity of a self-efficacy instrument for protective sexual behaviors. J Am Coll Health. 1998;47:113–21. doi: 10.1080/07448489809595631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carey MP, Maisto SA, Kalichman SC, Forsyth AD, Wright EM, Johnson BT. Enhancing motivation to reduce the risk of HIV infection for economically disadvantaged urban women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:531–41. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robertson A, Levin ML. AIDS knowledge, condom attitudes, and risk-taking sexual behavior of substance-abusing juvenile offenders on probation or parole. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11:450–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong LP, Chin CK, Low WY, Jaafar N. HIV/AIDS-related knowledge among Malaysian young adults: Findings from a nationwide survey. J Int AIDS Soc. 2008;10:148. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-10-6-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohtasham G, Shamsaddin N, Bazargan M, Anosheravan K, Elaheh M, Fazlolah G. Correlates of the intention to remain sexually inactive among male adolescents in an Islamic country: Case of the Republic of Iran. J Sch Health. 2009;79:123–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.0396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sales JM, Spitalnick J, Milhausen RR, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, et al. Validation of the worry about sexual outcomes scale for use in STI/HIV prevention interventions for adolescent females. Health Educ Res. 2009;24:140–52. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munro BH. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott awilliams and wilkins; 2005. Statistical methods for health care research. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nezami E, Schwartzer R, Jerusalem M. Berlin: 1996. Persian Adoption (Farsi) of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. Avalable from: http://www.userpage.fu-berlin.de/health/selfscal.htm . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller BC, Norton MC, Fan X, Christopherson CR. Pubertal Development, Parental Communication, and Sexual Values in Relation to Adolescent Sexual Behaviors. J Early Adolesc. 1998;18:27–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Houlihan AE, Stock ML, Pomery EA. A dual-process approach to health risk decision making: The prototype willingness model. Dev Rev. 2008;28:29–61. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nieswiadomy RM. 5th ed. Canada: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2008. Foundations of nursing research. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalantari KH. Tehran: Saba Publication; 2008. Structural equation modeling in social and economical research. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Movahed M, Shoaa S. On attitude towards HIV/AIDS among Iranian students (case study: High school students in Shiraz City) Pak J Biol Sci. 2010;13:271–8. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2010.271.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hedayati-Moghaddam MR. Knowledge of and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS in Mashhad, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:1321–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazloomy SS, Baghianimoghadam MH. Knowledge and attitude about HIV/AIDS of schoolteachers in Yazd, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:292–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramezani Tehrani F, Malek-Afzali H. Knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning HIV/AIDS among Iranian at-risk sub-populations. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:142–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khatony A, Nayery ND, Ahmadi F, Haghani H, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. The effectiveness of web-based and face-to-face continuing education methods on nurses’ knowledge about AIDS: A comparative study. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:41. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DiClemente RJ, Zorn J, Temoshok L. Adolescents and AIDS: A survey of knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about AIDS in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:1443–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.12.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Njie-Carr VP. Knowledge, attitudes, cultural, social and spiritual beliefs on healthseeking behaviors of Gambian adults with HIV/AIDS. Int J Cult Ment Health. 2009;2:118–28. doi: 10.1080/17542860903270961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ugarte WJ, Hogberg U, Valladares E, Essen B. Assessing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to HIV and AIDS in Nicaragua: A community-level perspective. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2013;4:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koopman C, Rotherman-Borus MJ, Henderson R, Bradley JS, Hunter J. Assessment of knowledge of AIDS and beliefs about AIDS prevention among adolescents. AIDS Educ Prev. 1990;2:58–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long CG, Krawczyk KM, Kenworthy NE. Assessing the sexual knowledge of women in secure settings: The development of a new screening measure. Br J Learn Disabil. 2013;41:51–65. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hughes AK, Admiraal KR. A Systematic Review of HIV/AIDS Knowledge Measures. Res Soc Work Pract. 2012;22:313–22. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lux KM, Petosa R. Preventing HIV Infection Among Juvenile Delinquents: Educational Diagnosis Using the Health Belief Model. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1994;15:145–64. doi: 10.2190/WTBA-HVC1-R16N-RRT5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahoney CA, Thombs DL, Ford OJ. Health belief and self-efficacy models: Their utility in explaining college student condom use. AIDS Educ Prev. 1995;7:32–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mukoma W, Flisher AJ, Helleve A, Aaro LE, Mathews C, Kaaya S, et al. Development and test-retest reliability of a research instrument designed to evaluate school-based HIV/AIDS interventions in South Africa and Tanzania. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37(Suppl 2):7–15. doi: 10.1177/1403494809103995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghafari M, Niknami S, Kazemnejad A, Mirzai E, Ghofranipour F. Desining validity and reliability of 10 Conceptual scales to Prevent HIV among Adolescents. Behboud. 2008;11:38–50. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Du Y, Kou J, Coghill D. The validity, reliability and normative scores of the parent, teacher and self report versions of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire in China. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosen L, Zucker D, Brody D, Engelhard D, Manor O. The effect of a handwashing intervention on preschool educator beliefs, attitudes, knowledge and self-efficacy. Health Educ Res. 2009;24:686–98. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Musiimenta A. A Controlled Pre-Post Evaluation of a Computer-based HIV/AIDS Education on Students’ Sexual Behaviors, Knowledge and Attitudes. Online J Public Health Inform. 2012;4(1) doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v4i1.4017. pii: ojphi.v4i1.4017 doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v4i1.4017. Epub 2012 May 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eshrati B, Asl RT, Dell CA, Afshar P, Millson PM, Kamali M, et al. Preventing HIV transmission among Iranian prisoners: Initial support for providing education on the benefits of harm reduction practices. Harm Reduct J. 2008;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oljira L, Berhane Y, Worku A. Assessment of comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge level among in-school adolescents in eastern Ethiopia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:17349. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.1.17349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gelibo T, Belachew T, Tilahun T. Predictors of sexual abstinence among Wolaita Sodo University Students, South Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2013;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]