Abstract

Inflammation is a natural host defensive process that is largely regulated by macrophages during the innate immune response. Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are proline-directed serine and threonine protein kinases that regulate many physiological and pathophysiological cell responses. p38 MAPKs are key MAPKs involved in the production of inflammatory mediators, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). p38 MAPK signaling plays an essential role in regulating cellular processes, especially inflammation. In this paper, we summarize the characteristics of p38 signaling in macrophage-mediated inflammation. In addition, we discuss the potential of using inhibitors targeting p38 expression in macrophages to treat inflammatory diseases.

1. Introduction

Inflammatory response is a basic protective immune process of the organism and is accompanied by symptoms such as redness, heat, swelling, and pain associated with damage to tissues or organs [1]. This is one of the mechanisms by which our body defends us from pathogens such as parasites, bacteria, viruses, and other harmful microorganisms. Diseases induced by chronic inflammation, including gastritis, colitis, dermatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, pulmonary diseases, and type II diabetes, damage millions of people's health every year. Of concern is the increase in prevalence of these chronic inflammatory diseases. Furthermore, there is growing evidence that inflammation is a critical initiation factor inducing a variety of other major diseases such as cancer, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, cardiovascular disease, neurological disorders, and pulmonary diseases [2–7]. Therefore, a better understanding of inflammation is clinically significant and could improve treatment strategies.

Macrophages within tissues play an essential role in the initiation, development, and resolution of inflammation [8–11]. Macrophages are white blood cells that are differentiated from monocytes. Their roles are to clean up damaged cells and pathogens by phagocytosis and to activate immune cells, such as neutrophils, dendritic cells, macrophages, and monocytes, in response to pathogens and diseases. They can be activated or deactivated during inflammatory processes depending on the signaling molecules produced. Stimulation signals include lipopolysaccharide (LPS), cytokines (interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)), other chemical mediators, and extracellular matrix proteins. A variety of membrane receptors are expressed on the surfaces of macrophages, including pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as dectin-1 and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [12, 13]. These receptors recognize activation signals and subsequently activate downstream protein kinases, eventually resulting in the stimulation of transcription factors including activator protein-1 (AP-1), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB).

Various intracellular proteins can initiate inflammation. p38 proteins are a class of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) that are major players during inflammatory responses, especially in macrophages. p38, also called RK or cytokinin-specific binding protein (CSBP), was identified in 1994 and is the mammalian ortholog of the yeast Hog1p MAP kinase [14]. p38 was isolated as a 38 kDa protein that is rapidly phosphorylated at a tyrosine residue in response to LPS stimulation, and the p38 gene was cloned through binding of the p38 protein with pyridinyl imidazole derivatives [15]. p38 expression is upregulated in response to inflammatory and stress stimuli, such as cytokines, ultraviolet irradiation, osmotic shock, and heat shock, and is involved in autophagy, apoptosis, and cell differentiation [16–20]. Accumulating evidence suggests that p38 plays an important role in arthritis and inflammation of the liver, kidney, brain, and lung and that it acts as a critical player in inflammatory diseases mediated by macrophages [21–23].

In this paper, we summarize the characteristics of p38 and highlight the physiological significance of p38 activation in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Moreover, we discuss the possibility of using plant extracts, natural products, and chemicals that target p38 as therapeutic drug candidates for the treatment of inflammatory diseases.

2. Structure and Function of p38 Kinases

2.1. The p38 Family

p38 family members are classified into four subtypes: α (MAPK14), β (MAPK11), γ (MAPK12/ERK6), and δ (MAPK13/SAPK4) (Table 1). Genes encoding p38α and p38β show 74% sequence homology, whereas γ and δ are more distant relatives, with approximately 62% sequence identity [24–26]. Genes encoding p38α and p38β are ubiquitously expressed within tissues, and especially highly expressed in heart and brain. However, p38γ and p38δ show tissue-specific expression patterns; p38γ is highly expressed in skeletal muscle, whereas p38δ expression is concentrated in the kidneys, lungs, pancreas, testis, and small intestine [27]. In addition, p38γ expression can be induced during muscle differentiation, and its expression can also be developmentally regulated. Moreover, we demonstrated very high expression of the active form of p38 in inflammatory diseases, such as gastritis, colitis, arthritis, and hepatitis [28, 29] (unpublished data). p38α and p38δ are abundantly expressed in macrophages, whereas p38β is undetectable. p38α and p38δ are also expressed in endothelial cells, neutrophils, and CD4+ T cells, whereas p38β is abundant in endothelial cells. These findings indicate that, even though the four p38 family members share sequence homology, their expression is cell- and tissue dependent and their functions may therefore be different.

Table 1.

p38 family members and their functions in inflammatory responses.

| p38 isoform (molecular weight, kDa) | Distribution in tissue | Expressing cells | Inflammatory responses | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p38α (38) | Ubiquitous | Macrophages, neutrophils | Cytokine production (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6); regulation of enzymes (iNOS, COX2); involvement of cell proliferation and differentiation; induction of cardiomyocyte apoptosis. | [21, 27, 73] |

|

| ||||

| p38β (39) | Ubiquitous | Endothelial cells, T cells | Regulation of cell differentiation; induction of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. | [21, 27, 73] |

|

| ||||

| p38γ (43) | Skeletal muscle | Not detected | Muscle differentiation. | [25, 27, 73] |

|

| ||||

| p38δ (40) | Lung, kidney, testis, pancreas, and small intestine | T cells, endothelial cells, and macrophages | Developmentally regulated; involvement of cell differentiation. | [26, 27, 73] |

2.2. p38 Structure and Domains

p38 kinases have two domains: a 135 amino acid N-terminal domain and a 225 amino acid C-terminal domain. The main secondary structure of the N-terminal domain is β-sheets, while the C-terminal domain has a α-helical structure. The catalytic site is located in the region linking the two domains. The phosphorylation lip of p38 consists of 13 residues, Leu-171–Val-183, and the protein is activated by phosphorylation of a single threonine (Thr-180) and a single tyrosine residue (Tyr-182) in the lip [30]. Moreover, in Drosophila p38 MAPK, phosphorylation of tyrosine-186 was detected exclusively in the nucleus following osmotic stress [31]. p38 isoforms show various three-dimensional structures with differences in the orientation of the N- and C-terminal domains, resulting in different sized ATP-binding pockets [32].

2.3. Activation of the p38 Response

p38 kinases are activated by environmental and cellular stresses including pathogens, heat shock, growth factors, osmotic shock, ultraviolet irradiation, and cytokines. Moreover, various signaling events are able to stimulate p38 kinases, for example, insulin signaling. Interestingly, with respect to inflammatory responses, a number of studies have reported p38 regulation in macrophages treated with LPS, endothelial cells stimulated with TNF-α, U1 monocytic cells treated with IL-18, and human neutrophils activated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), LPS, TNF-α, and fMLP [33, 34]. It should also be noted that p38 activation in different cell types is dependent on the type of stimulus.

In addition, a number of studies have reported that distinct upstream kinases selectively activate p38 isoforms. p38 family kinases are all activated by MAP kinase kinases (MKKs). MKK6 activates all four p38 isoforms, while MKK3 can activate p38α, β, and δ, but not p38γ [35], and MKK4 activates p38α and δ [36]. This implies that p38 isoforms can be coactivated by the same upstream regulators and regulated specifically through different regulators.

2.4. p38 Deficiency

p38α deficiency affects placental development and erythropoietin expression and can result in embryonic lethality [37–40]. Tetraploid rescue of placental defects in p38α −/− embryos indicated that p38α was required for extraembryonic development, while it was not necessary for embryo development or adult mice survival. In accordance with the phenotype of p38α knockouts, knockout of two p38 activators, namely, MKK3 and MKK6, led to placental and vascular defects and induced embryonic lethality [41]. In contrast, p38β −/− mice were viable and exhibited no obvious health defects. Neither transcription of p38-dependent immediate-early genes, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, nor T cell development was influenced by the loss of p38β [42, 43]. Furthermore, mice harboring a T106M mutation in p38α resisted the drug inhibitory effect of collagen antibody-induced arthritis and LPS-induced TNF production, whereas the same mutation in p38β had the opposite effect [44], and p38β knockout mice responded normally to inflammatory stimuli. Single knockouts of either p38γ or p38δ, and even a double knockout, were viable [45]. However, reduced production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 in stimulated macrophages isolated from p38 γ/δ null mice has been observed, which indicates that p38 γ/δ are important regulatory components of the innate immune response [46]. Taken together, these findings suggest that p38α is the critical isoform in inflammatory responses but that other subtypes also play important roles.

2.5. Regulation of p38-Activated Signaling

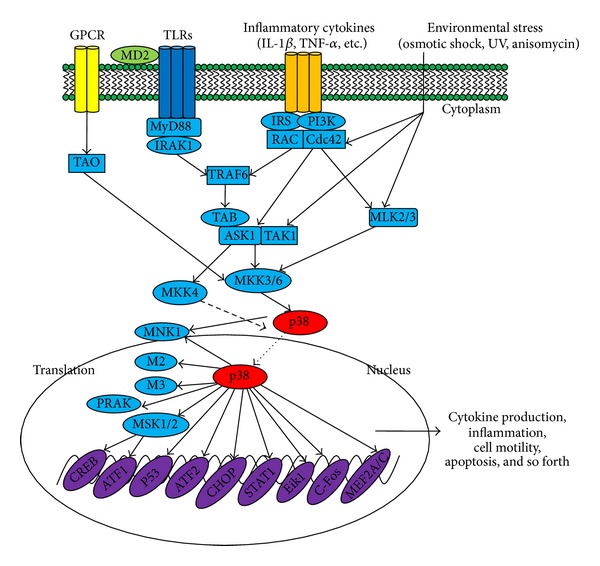

Because p38 signaling can be activated by a variety of stimuli, the receptors and downstream pathways are diverse (Figure 1). MTK1, mixed lineage kinase (MLK) 2/3, apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1, and transforming growth factor β-activated kinase (TAK) 1 are all MKK kinases (MAP3Ks) that have been demonstrated to activate p38 signaling [47–54]. Furthermore, different kinases can mediate different signals. Among upstream proteins, Cdc42 and Rac are recognized as critical intermediates of p38 activity [55–57]. Many studies have also reported that p21-activated kinases (PAKs) can be stimulated by binding to Cdc42 and Rac in vitro and subsequently activate a p38 response [58–61]. In addition, Mst1, a mammalian homologue of Ste20, was reported to stimulate MKK6, p38, MKK7, and JNK [62]. However, there are no reports of the involvement of MTK1 and Mst1 in p38 responses in macrophages.

Figure 1.

p38-regulated signaling pathways in inflammatory responses. Inflammation-derived cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1, TLR ligands such as LPS, poly(I:C), and peptidoglycan, as a environmental stresses, stimulate the phosphorylation of p38, leading to the activation of transcription factors such as AP-1 family. Subsequent expression of inflammatory genes by these transcription factors mediates various inflammatory responses including cytokine production, migration, and apoptosis of macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils.

There are numbers of substrates downstream of p38 signaling pathways. MAP kinase-activated protein kinase 2 (M2) and M3 were the first p38 substrates identified [63, 64]. Phosphorylated M2 or M3 can activate a variety of substrates, such as small heat shock protein 27 (HSP27), CREB, and activating transcription factor (ATF) 1 [65, 66]. To date, several other proteins have also been identified as downstream substrates of p38, such as mitogen- and stress-activated kinase (MSK), p38-regulated/activated kinase (PRAK), and MAP kinase interaction protein kinase (MNK1) [67–70]. Various novel proteins have also been shown to be direct substrates of p38α, including Ahnak, Iws1, Grp78, Pgrmc, Prdx6, and Ranbp2 [71]. Additionally, TPL2/ERK1/2 has been shown to be downstream kinases controlled by p38 γ and δ isoforms [46].

Phosphatases that downregulate p38 activity have also been identified. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatases (MKPs) can recognize MAPKs by recognizing the TXY amino acid motif and consequently dephosphorylate and deactivate them. MKP-1, MKP-4, MKP-5, and MKP7 can effectively dephosphorylate p38α and p38β [72–75]. However, right now, MKPs cannot dephosphorylate p38γ or p38δ as shown by other researchers [73, 76].

Several transcription factors in the nucleus can be phosphorylated and activated by p38 MAPKs, such as activating transcription factor 1 and 2 (ATF-1, ATF-2), myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2), CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs), SRF accessory protein-1 (Sap1), p53, and E26 transformation-specific sequence-1 (ETS-1) [77–82] (Figure 1).

3. p38 Functions in Macrophage-Mediated Inflammatory Responses and Diseases

Macrophages are the first line of defense of organisms against pathogens. They represent a major cell population distributed in most tissues, and their numbers increase massively in inflammatory diseases. In particular, macrophages are critically involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and produce a variety of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that contribute to cartilage and bone degradation. They are also the predominant cells in the synovial lining and sublining of patients with RA [83]. Macrophages also play a central role in the development of type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Macrophage accumulation in kidney, coronary arteries, nerves, and epiretinal membrane is regarded as one of major causing factors in terms of type 2 diabetic complications, including nephropathy, atherosclerosis, neuropathy, and retinopathy [84–88]. Components of the diabetic milieu, including high glucose, advanced glycation end products, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein, promote macrophage accumulation and activation within diabetic tissues [89]. Macrophage depletion studies have also demonstrated the crucial role of macrophages in the development of diabetic complications [89]. Moreover, macrophages play a pivotal role in the clearance of pulmonary pathogens. Alveolar macrophages (AM) constitute more than 90% of the cells present in bronchoalveolar lavage of naïve tissues [90]. AM can rapidly clear bacteria from airways and cellular debris, help to depress the immune characteristics of the airways, and aid in lung parenchyma modeling [90]. Furthermore, macrophages have significant roles in metabolic diseases, atherosclerosis, bowel disease, and liver fibrosis [91–94]. The fundamental roles of macrophages in inflammation highlight the need for macrophage-targeted studies and therapeutics.

Accumulating evidence suggests that p38 plays an essential role in macrophage-mediated inflammation. p38α is involved in the expression of proinflammatory mediators in macrophages such as IL-1β, TNF-α, PGE2, and IL-12 [95–97] as well as COX-2, IL-8, IL-6, IL-3, IL-2, and IL-1, all of which contain AU-rich elements (AREs) in their 3′ untranslated regions to which p38 binds [98]. Moreover, p38 can regulate the production of endothelial vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), which participates in cell proliferation and differentiation of the immune response [99]. Furthermore, p38 is associated with various inflammatory diseases, including endotoxin-induced shock, collagen-induced arthritis, granuloma, diabetes, and acute lung inflammation [100–103], as well as joint diseases, including synovial inflammation, cartilage damage, and bone loss [104]. In contrast, p38β and δ also play important roles in regulation of TPA-induced skin inflammation and tumor development [105, 106]. In addition, a large number of reports have suggested a close correlation between p38 and cell apoptosis, cell cycle progression, and differentiation [107–110].

4. Development of p38-Targeted Drugs as New Anti-Inflammatory Therapeutics

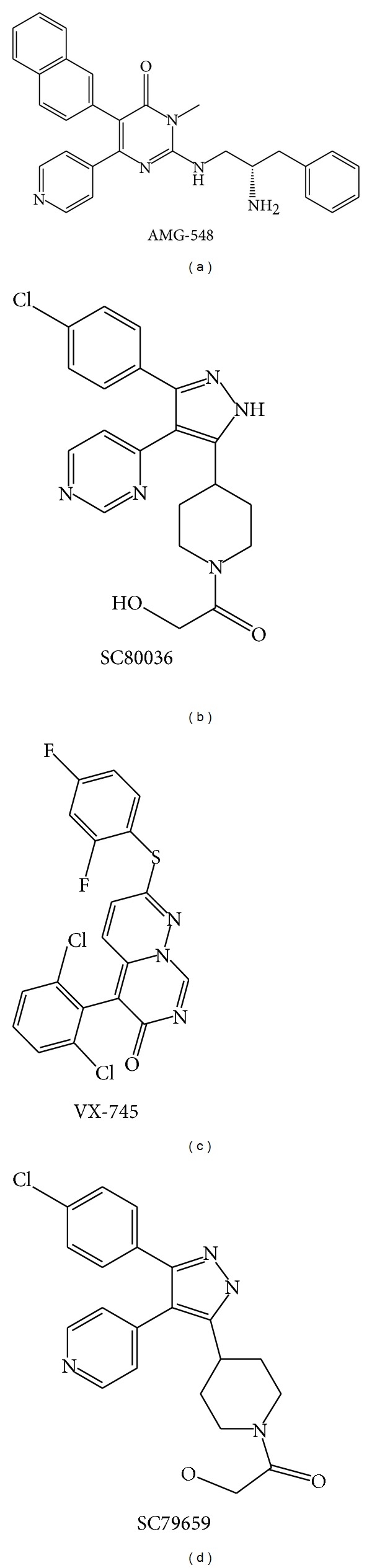

p38 MAPK signaling plays a significant role in the inflammatory response and other physiological processes. A better understanding of the functional and biological significance of p38 in inflammation has led to the development of p38 inhibitors. Currently, a number of p38 inhibitors have been developed such as AMG-548, SC-80036, SC-79659, and VXs (Figure 2) [111]; however, few studies have reported their effects on macrophages.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of representative novel p38 inhibitors. Promising therapeutic activities of these inhibitors against inflammatory diseases such as RA encourage the continuous progression for clinical trials.

4.1. Discovery

p38 signaling and specific p38 inhibitors were identified simultaneously. A series of pyridinyl imidazole anti-inflammatory agents, such as bicyclic pyridinyl imidazoles SKF-86002, SB203580, and SB202190 [15, 112–116], were first found to inhibit p38 activity [104, 117]. SB inhibitors can antagonize p38 by competing for the ATP-binding pocket, and it has been suggested that Thr-106 could be important for this interaction [115].

4.2. Crude Plant Extracts

Natural plant extracts that target p38 are promising therapeutics for the treatment of inflammatory diseases (Table 2). For example, Scutellaria baicalensis extract attenuates MAPK phosphorylation, especially p38 activity, resulting in inhibition of inflammatory mediators such as COX-2, iNOS, L-1β, IL-12, IL-6, IL-2, PGE2, and TNF-α in RAW 264.7 cells treated with LPS [118]. Phaseolus angularis ethanol extract suppressed the release of PGE2 and NO in macrophages activated by LPS-, Poly(I:C)-, or pam3CSK through regulation of TAK1/p38 pathways and, moreover, it ameliorated gastritis induced by EtOH/HCl in mice, which implies a close relationship between p38 and gastritis [119]. Archidendron clypearia extract suppressed the production of PGE2 in activated RAW264.7 and peritoneal macrophages, as well as gastritis lesions in mouse stomachs exposed to EtOH/HCl [28]. Unfortunately, p38 is not the only target of these extracts; they contain several other active ingredients and therefore are not good candidates for the development of p38-specific inhibitors. However, they are effective at treating inflammatory diseases because of their multiple targets and their ability to improve body's homeostatic defense responses [120–123]. Meanwhile, as reported previously [124], during covering years 1981–2006, of the 974 small molecule new chemical entities, 63% were naturally derived or semisynthetic derivatives of naturally occurring products, which indicate the importance of plant extract in the drug development [124]. In addition, we and other groups have found that various traditional plant extracts that target p38 kinase can reduce the symptoms of inflammatory diseases (unpublished data), such as gastritis, colitis, arthritis, and hepatitis [28, 29]. Plant extract data are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Plant extracts that inhibit the p38 signaling in macrophages.

| Plant | Action target of p38 | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Archidendron clypearia | Suppression of PGE2 production; amelioration of EtOH/HCl-induced gastritis | [28] |

| Scutellaria baicalensis | Inhibition of iNOS, COX-2, PGE2, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α expression | [118] |

| Phaseolus angularis | Suppression of the release of PGE2 and NO; amelioration of EtOH/HCl-induced gastritis | [119] |

| Artemisia vestita | Inhibition of TNF-α release; beneficial for the treatment of endotoxin shock or sepsis | [141] |

| Boswellia serrata | Inhibition of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 | [142] |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa | Suppression of nitrite, PGE2 release, and hepatic inflammation | [143] |

| Clinopodium vulgare | Suppression of NO production; MMP-9 activation | [144] |

| Eriobotryae folium | Suppression of LPS-induced NO and PGE2 production | [145] |

| Elaeocarpus petiolatus | Inhibition of the production of PGE2, TNF-α, and IL-1β | [146] |

| Polygonum cuspidatum | Inhibition of IL-6, TNF-α, NO, and PGE2 | [147] |

| Ginkgo biloba | Inhibition of LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression | [148] |

| Lycium chinense | Inhibition of LPS-induced NO, PGE2, TNF-α, and IL-6 production | [149] |

| Hopea odorata | Inhibition of NO, PGE2, and TNF-α release; amelioration of gastritis and ear edema | [150] |

4.3. Plant-Derived Compounds

Several compounds from natural products inhibit p38 activity and inflammatory responses (Table 3). Sugiol, an aditerpene that was isolated and purified from alcohol extracts of the bark of Calocedrus formosana, effectively decreased the production of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), IL-1β, and TNF-α in LPS-stimulated macrophages through regulation of MAPKs [125]. Quercetin, a plant-derived flavonoid that is widely distributed in fruits and vegetables, strongly decreased the expression of the inflammatory cytokines iNOS and TNF-α by targeting both MAPK (ERK and p38) and IκBα signaling pathways [126, 127]. Sulfur-containing compounds from garlic inhibited the production of NO, PGE2, and proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in macrophages by suppressing p38 transduction pathways [128]. A summary of natural products targeting p38 is provided in Table 3. These studies indicate that natural products inhibiting p38 activity exhibit strong anti-inflammatory properties, and are therefore potential therapeutic drug candidates for inflammatory diseases. Moreover, studies of natural compounds, in addition to elucidating why these extracts have strong anti-inflammatory effects, can also aid the design of novel p38 inhibitors to treat inflammatory diseases.

Table 3.

Naturally occurring compounds that inhibit p38 signaling in macrophages.

| Compound | Action target of p38 | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Sugiol | Inhibition of IL-1β, TNF-α, and ROS production | [151] |

| Quercetin | Inhibition of NO and TNF-α | [114] |

| Ajoenes | Inhibition of NO, PGE2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 production | [116] |

| Ginsan | Enhanced phagocytic activity; downregulation of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, and IL-18 | [152] |

| 4-Methoxyhonokiol | Inhibition of iNOS and COX-2 expression; inhibition of dye leakage and paw swelling | [153] |

| Schisandrin | Suppression of NO production and PGE2 release | [154] |

| Rengyolone | Inhibition of iNOS and COX-2 expression | [155] |

| Pseudocoptisine | Inhibition of proinflammatory mediators such as iNOS, COX-2, TNF-α, and IL-6 | [156] |

| Mycoepoxydiene | Inhibition of LPS-induced proinflammatory mediators including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and NO | [157] |

| Britanin | Suppression of NO, PGE2, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 | [158] |

| Hyperin | Inhibition of NO production through suppression of iNOS expression | [159] |

| Carnosol | Inhibition of LPS-stimulated NO production; antioxidative activity | [160] |

4.4. Novel Inhibitors

Pharmaceutical companies and researchers have worked hard to develop novel, safe, and specific p38 inhibitors. Based on the importance of p38α in inflammation, people have focused on inhibitors for this isoform rather than the other isoforms. ML3403, a SB203580 analogue, represses the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8. It can bind to both active and inactive forms of p38α kinase, which may reduce asthma-induced airway inflammation and remodeling [129]. AS1940477 has been shown to inhibit the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, PEG2, and MMP3 at very low concentrations. Moreover, it can reduce the enzyme activity of both p38 α and β but has no effect on 100 other kinases, including p38γ and δ. It has been shown in rats experiment that low doses of this compound can also reduce the expression of LPS- and Con A-stimulated proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6 [130]. Pamapimod strongly suppresses p38 α and β activity and therefore the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. It also shows high specific activity; when tested for binding to 350 kinases, it only bound to four other kinases in addition to p38. Furthermore, it can reduce clinical signs of inflammatory diseases, such as arthritis, bone loss, and renal diseases. Consistent with this, it inhibited TNF-α production in RA synovial explants and reduced bone loss in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Meanwhile, it increased pain tolerance in a rat model of hyperalgesia [131]. Examples of other newly synthesized compounds are GSK-681323 to treat rheumatoid arthritis, SCIO-469 to treat multiple myeloma and dental pain, and RWJ67657 that was developed as an anti-inflammatory drug, all of which inhibit p38 activity [98]. In summary, most of these inhibitors were designed based on the structure of SB203580 but show more specific and stronger activity. They are therefore promising therapeutic agents for inflammatory diseases.

4.5. Inhibitors in Human Clinical Trials

Based on the importance of p38 MAPK in disease development, inhibition of p38 was regarded as a promising therapeutic strategy to control inflammatory diseases. Right now, effectiveness of some p38 inhibitors is currently under evaluation in clinical trials to treat human diseases. For example, it has been reported that PH797804 and losmapimod were able to improve lung function parameters and to attenuate dyspnoea in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease symptoms [132, 133]. Also, losmapimod was reported to reduce vascular inflammation in the most inflamed regions in patients with atherosclerosis [134]. Clinical and histological improvements linked to the inhibition of TNF-α level were clearly seen by p38 MAPK inhibitor adalimumab in lesional psoriatic skin [135]. Moreover, it was found that pamapimod can clearly alleviate various rheumatoid arthritis symptoms when coadministered with methotrexate [136]. Besides, there are still many other inhibitors which are ongoing clinical trials as summarized in Table 4 [137–140].

Table 4.

p38 inhibitors under human clinical trials.

| Compound | Clinical trials | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| PH797804 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | [132] |

| Losmapimod (GW856553) | COPD; atherosclerosis | [133, 134] |

| Adalimumab | Antipsoriatic | [135] |

| Pamapimod | Rheumatoid arthritis | [136] |

| VX-745 | Werner syndrome | [137] |

| BMS-582949 | Rheumatoid arthritis | [138] |

| SB-681323 | Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); neuropathic pain | [139, 140] |

5. Summary and Perspectives

Inflammation has attracted great interest because of its significant role in several major diseases and the need to develop better ways to treat these diseases. Importantly, because inflammatory responses are largely mediated by macrophages, functional studies of macrophages in inflammation are crucial. Investigation of the roles of p38 MAPKs is particularly relevant as these are essential protein kinases in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. A number of studies have indicated that p38 plays a significant role in inflammatory diseases mediated by macrophages, and, as a consequence, several p38 inhibitors have been developed to treat inflammatory diseases. However, most of these inhibitors have shortcomings, such as low specificity, low efficacy, and high toxicity. As a result, new p38 inhibitors are urgently required. We are optimistic that novel and safe p38 inhibitors that possess strong anti-inflammatory properties will be developed in the near future to treat inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a Grant (HI12C0050) of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea.

Abbreviations

- MAPKs:

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

- COX2:

Cyclooxygenase-2

- TNF-α:

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- PGE2:

Prostaglandin E2

- NF-κB:

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- AP-1:

Activator protein-1

- CREB:

cAMP response element-binding protein

- CSBP:

Cytokinin-specific binding protein

- PMA:

Phorbol myristate acetate

- LPS:

Lipopolysaccharide

- MKPs:

MAP kinase phosphatases

- MKKs:

MAPK kinases

- PAK:

p21-activated kinases

- HSP27:

Heat shock protein 27

- TLRs:

Toll-like receptors

- PRRs:

Pattern recognition receptors

- MNK1:

MAP kinase interaction protein kinase

- ATF-2:

Activating transcription factor-2

- MEF2C:

Myocyte enhancer factor 2C

- PRAK:

p38-regulated/activated kinase

- MSK:

Mitogen- and stress-activated kinase

- ARE:

AU-rich elements

- ICAM:

Cell adhesion molecule.

Conflict of Interests

The authors report no conflict of interests. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Authors' Contribution

Yanyan Yang, Seung Cheol Kim, and Tao Yu contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Ferrero-Miliani L, Nielsen OH, Andersen PS, Girardin SE. Chronic inflammation: importance of NOD2 and NALP3 in interleukin-1β generation. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2007;147(2):227–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eiro N, Vizoso FJ. Inflammation and cancer. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2012;4(3):62–72. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v4.i3.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee YW, Kim PH, Won HL, Hirani AA. Interleukin-4, oxidative stress, vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Biomolecules and Therapeutics. 2010;18(2):135–144. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2010.18.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wyss-Coray T, Rogers J. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease-a brief review of the basic science and clinical literature. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012;2(1) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006346.a006346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urrutia P, Aguirre P, Esparza A, et al. Inflammation alters the expression of DMT1, FPN1 and hepcidin, and it causes iron accumulation in central nervous system cells. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2013;126(4):541–549. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wee Yong V. Inflammation in neurological disorders: a help or a hindrance? Neuroscientist. 2010;16(4):408–420. doi: 10.1177/1073858410371379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Provinciali M, Cardelli M, Marchegiani F. Inflammation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and aging. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2011;17(supplement 1):S3–S10. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000410742.90463.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu T, Yi YS, Yang Y, Oh J, Jeong D, Cho JY. The pivotal role of TBK1 in inflammatory responses mediated by macrophages. Mediators of Inflammation. 2012;2012:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/979105.979105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujiwara N, Kobayashi K. Macrophages in inflammation. Current Drug Targets. 2005;4(3):281–286. doi: 10.2174/1568010054022024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duffield JS. The inflammatory macrophage: a story of Jekyll and Hyde. Clinical Science. 2003;104(1):27–38. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong JJ, Jang SE, Joh EH, Han MJ, Kim DH. Kalopanaxsaponin B ameliorates TNBS-induced colitis in mice. Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 2012;20(5):457–462. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2012.20.5.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor PR, Martinez-Pomares L, Stacey M, Lin H-H, Brown GD, Gordon S. Macrophage receptors and immune recognition. Annual Review of Immunology. 2005;23:901–944. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batbayar S, Lee DH, Kim HW. Immunomodulation of fungal beta-glucan in host defense signaling by dectin-1. Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 2012;20(5):433–445. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2012.20.5.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Rourke SM, Herskowitz I. The Hog1 MAPK prevents cross talk between the HOG and pheromone response MAPK pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Genes and Development. 1998;12(18):2874–2886. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JC, Laydon JT, McDonnell PC, et al. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372(6508):739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huh JE, Jung IT, Choi J, et al. The natural flavonoid galangin inhibits osteoclastic bone destruction and osteoclastogenesis by suppressing NF-kappaB in collagen-induced arthritis and bone marrow-derived macrophages. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;698(1–3):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim M, Li YX, Dewapriya P, Ryu B, Kim SK. Floridoside suppresses pro-inflammatory responses by blocking MAPK signaling in activated microglia. BMB Reports. 2013;46(8):398–403. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2013.46.8.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schieven GL. The biology of p38 kinase: a central role in inflammation. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;5(10):921–928. doi: 10.2174/1568026054985902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajashekhar G, Kamocka M, Marin A, et al. Pro-inflammatory angiogenesis is mediated by p38 MAP kinase. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2011;226(3):800–808. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark AR, Dean JL. The p38 MAPK pathway in rheumatoid arthritis: a sideways look. The Open Rheumatology Journal. 2012;6:209–219. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren F, Zhang HY, Piao ZF, et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3b activity regulates Toll-like receptor 4-mediated liver inflammation. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2012;20(9):693–697. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim AK, Tesch GH. Inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Mediators of Inflammation. 2012;2012:12 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/146154.146154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko HM, Joo SH, Kim P, et al. Effects of Korean red ginseng extract on tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in cultured rat primary astrocytes. Journal of Ginseng Research. 2013;37(4):401–412. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Y, Chen C, Li Z, et al. Characterization of the structure and function of a new mitogen- activated protein kinase (p38β) The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(30):17920–17926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z, Jiang Y, Ulevitch RJ, Han J. The primary structure of p38γ: a new member of p38 group of MAP kinases. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1996;228(2):334–340. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S, McDonnell PC, Gum RJ, Hand AT, Lee JC, Young PR. Novel homologues of CSBP/p38 MAP kinase: activation, substrate specificity and sensitivity to inhibition by pyridinyl imidazoles. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;235(3):533–538. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hale KK, Trollinger D, Rihanek M, Manthey CL. Differential expression and activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase α, β, γ, and δ in inflammatory cell lineages. Journal of Immunology. 1999;162(7):4246–4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang WS, Jeong D, Nam G, et al. AP-1 pathway-targeted inhibition of inflammatory responses in LPS-treated macrophages and EtOH/HCl-treated stomach by Archidendron clypearia methanol extract. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;146(2):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu T, Shim J, Yang Y, et al. 3-(4-(tert-Octyl)phenoxy)propane-1,2-diol suppresses inflammatory responses via inhibition of multiple kinases. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2012;83(11):1540–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Harkins PC, Ulevitch RJ, Han J, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. The structure of mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 at 2.1-Å resolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(6):2327–2332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han S-J, Choi K-Y, Brey PT, Lee W-J. Molecular cloning and characterization of a Drosophila p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(1):369–374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel SB, Cameron PM, O'keefe SJ, et al. The three-dimensional structure of MAP kinase p38Β: different features of the ATP-binding site in p38Β compared with p38α . Acta Crystallographica D. 2009;65(8):777–785. doi: 10.1107/S090744490901600X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nick JA, Avdi NJ, Gerwins P, Johnson GL, Worthen GS. Activation of a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in human neutrophils by lipopolysaccharide. Journal of Immunology. 1996;156(12):4867–4875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shapiro L, Puren AJ, Barton HA, et al. Interleukin 18 stimulates HIV type 1 in monocytic cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(21):12550–12555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keesler GA, Bray J, Hunt J, et al. Purification and activation of recombinant p38 isoforms α, β, γ and δ . Protein Expression and Purification. 1998;14(2):221–228. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.0947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang Y, Gram H, Zhao M, et al. Characterization of the structure and function of the fourth member of p38 group mitogen-activated protein kinases, p38δ . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(48):30122–30128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams RH, Porras A, Alonso G, et al. Essential role of p38α MAP kinase in placental but not embryonic cardiovascular development. Molecular Cell. 2000;6(1):109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen M, Svensson L, Roach M, Hambor J, McNeish J, Gabel CA. Deficiency of the stress kinase p38α results in embryonic lethality: characterization of the kinase dependence of stress responses of enzyme-deficient embryonic stem cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2000;191(5):859–869. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mudgett JS, Ding J, Guh-Siesel L, et al. Essential role for p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase in placental angiogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(19):10454–10459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180316397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tamura K, Sudo T, Senftleben U, Dadak AM, Johnson R, Karin M. Requirement for p38α in erythropoietin expression: a role for stress kinases in erythropoiesis. Cell. 2000;102(2):221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brancho D, Tanaka N, Jaeschke A, et al. Mechanism of p38 MAP kinase activation in vivo . Genes and Development. 2003;17(16):1969–1978. doi: 10.1101/gad.1107303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beardmore VA, Hinton HJ, Eftychi C, et al. Generation and characterization of p38β (MAPK11) gene-targeted mice. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2005;25(23):10454–10464. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10454-10464.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xing B, Bachstetter AD, van Eldik LJ. Deficiency in p38beta MAPK fails to inhibit cytokine production or protect neurons against inflammatory insult in in vitro and in vivo mouse models. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056852.e56852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Keefe SJ, Mudgett JS, Cupo S, et al. Chemical genetics define the roles of p38α and p38β in acute and chronic inflammation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(48):34663–34671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sabio G, Arthur JSC, Kuma Y, et al. p38γ regulates the localisation of SAP97 in the cytoskeleton by modulating its interaction with GKAP. The EMBO Journal. 2005;24(6):1134–1145. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Risco A, del Fresno C, Mambol A, et al. p38gamma and p38delta kinases regulate the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-induced cytokine production by controlling ERK1/2 protein kinase pathway activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(28):11200–11205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207290109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cuenda A, Dorow DS. Differential activation of stress-activated protein kinase kinases SKK4/MKK7 and SKK1/MKK4 by the mixed-lineage kinase-2 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MKK) kinase-1. The Biochemical Journal. 1998;333, part 1:11–15. doi: 10.1042/bj3330011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takekawa M, Posas F, Saito H. A human homolog of the yeast Ssk2/Ssk22 MAP kinase kinase kinases, MTK1, mediates stress-induced activation of the p38 and JNK pathways. The EMBO Journal. 1997;16(16):4973–4982. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirai S-I, Katoh M, Terada M, et al. MST/MLK2, a member of the mixed lineage kinase family, directly phosphorylates and activates SEK1, an activator of c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(24):15167–15173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tibbles LA, Ing YL, Kiefer F, et al. MLK-3 activates the SAPK/JNK and p38/RK pathways via SEK1 and MKK3/6. The EMBO Journal. 1996;15(24):7026–7035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, et al. Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science. 1997;275(5296):90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lund S, Porzgen P, Mortensen AL, et al. Inhibition of microglial inflammation by the MLK inhibitor CEP-1347. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;92(6):1439–1451. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu HL, Zhang HQ, Iles KE, et al. The Adp-stimulated NADPH oxidase activates the ASK-1/MMK4/JNK pathway in alveolar macrophages. Free Radical Research. 2006;40(8):865–874. doi: 10.1080/10715760600758514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang Y, Moh SH, Yu T, et al. Methanol extract of Osbeckia stellata suppresses lipopolysaccharide- and HCl/ethanol-induced inflammatory responses by inhibiting Src/Syk and IRAK1. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;143(3):876–883. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang S, Han J, Sells MA, et al. Rho family GTPases regulate p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase through the downstream mediator Pak1. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(41):23934–23936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bagrodia S, Derijard B, Davis RJ, Cerione RA. Cdc42 and PAK-mediated signaling leads to Jun kinase and p38 mitogen- activated protein kinase activation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(47):27995–27998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.27995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yano M, Matsumura T, Senokuchi T, et al. Statins activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages. Circulation Research. 2007;100(10):1442–1451. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000268411.49545.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin GA, Bollag G, McCormick F, Abo A. A novel serine kinase activated by rac1/CDC42Hs-dependent autophosphorylation is related to PAK65 and STE20. The EMBO Journal. 1995;14(17):p. 4385. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manser E, Leung T, Salihuddin H, Zhao Z-S, Lim L. A brain serine/threonine protein kinase activated by Cdc42 and Rac1. Nature. 1994;367(6458):40–46. doi: 10.1038/367040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Knaus UG, Morris S, Dong H-J, Chernoff J, Bokoch GM. Regulation of human leukocyte p21-activated kinases through G protein-coupled receptors. Science. 1995;269(5221):221–223. doi: 10.1126/science.7618083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rousseau S, Dolado I, Beardmore V, et al. CXCL12 and C5a trigger cell migration via a PAK1/2-p38α MAPK-MAPKAP-K2-HSP27 pathway. Cellular Signalling. 2006;18(11):1897–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Graves JD, Gotoh Y, Draves KE, et al. Caspase-mediated activation and induction of apoptosis by the mammalian Ste20-like kinase Mst1. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17(8):2224–2234. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zu Y-L, Wu F, Gilchrist A, Ai Y, Labadia ME, Huang C-K. The primary structure of a human MAP kinase activated protein kinase 2. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1994;200(2):1118–1124. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McLaughlin MM, Kumar S, McDonnell PC, et al. Identification of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase-activated protein kinase-3, a novel substrate of CSBP p38 MAP kinase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(14):8488–8492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guay J, Lambert H, Gingras-Breton G, Lavoie JN, Huot J, Landry J. Regulation of actin filament dynamics by p38 map kinase-mediated phosphorylation of heat shock protein 27. Journal of Cell Science. 1997;110, part 3:357–368. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tan Y, Rouse J, Zhang A, Cariati S, Cohen P, Comb MJ. FGF and stress regulate CREB and ATF-1 via a pathway involving p38 MAP kinase and MAPKAP kinase-2. The EMBO Journal. 1996;15(17):4629–4642. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fukunaga R, Hunter T. MNK1, a new MAP kinase-activated protein kinase, isolated by a novel expression screening method for identifying protein kinase substrates. The EMBO Journal. 1997;16(8):1921–1933. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Waskiewicz AJ, Flynn A, Proud CG, Cooper JA. Mitogen-activated protein kinases activate the serine/threonine kinases Mnk1 and Mnk2. The EMBO Journal. 1997;16(8):1909–1920. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.New L, Jiang Y, Zhao M, et al. PRAK, a novel protein kinase regulated by the p38 MAP kinase. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17(12):3372–3384. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deak M, Clifton AD, Lucocq JM, Alessi DR. Mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1) is directly activated by MAPK and SAPK2/p38, and may mediate activation of CREB. The EMBO Journal. 1998;17(15):4426–4441. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Knight JD, Tian R, Lee RE, et al. A novel whole-cell lysate kinase assay identifies substrates of the p38 MAPK in differentiating myoblasts. Skeletal Muscle. 2012;2:p. 5. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keyse SM. An emerging family of dual specificity MAP kinase phosphatases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1265(2-3):152–160. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(94)00211-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ono K, Han J. The p38 signal transduction pathway Activation and function. Cellular Signalling. 2000;12(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(99)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Camps M, Nichols A, Gillieron C, et al. Catalytic activation of the phosphatase MKP-3 by ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science. 1998;280(5367):1262–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Theodosiou A, Smith A, Gillieron C, Arkinstall S, Ashworth A. MKP5, a new member of the MAP kinase phosphatase family, which selectively dephosphorylates stress-activated kinases. Oncogene. 1999;18(50):6981–6988. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tanoue T, Yamamoto T, Maeda R, Nishida E. A Novel MAPK Phosphatase MKP-7 Acts Preferentially on JNK/SAPK and p38α and β MAPKs. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(28):26629–26639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Janknecht R, Hunter T. Convergence of MAP kinase pathways on the ternary complex factor Sap-1a. The EMBO Journal. 1997;16(7):1620–1627. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang X, Ron D. Stress-induced phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor CHOP (GADD153) by p38 MAP kinase. Science. 1996;272(5266):1347–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Han J, Jiang Y, Li Z, Kravchenko VV, Ulevitch RJ. Activation of the transcription factor MEF2C by the MAP kinase p38 in inflammation. Nature. 1997;386(6622):296–299. doi: 10.1038/386296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao M, New L, Kravchenko VV, et al. Regulation of the MEF2 family of transcription factors by p38. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19(1):21–30. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Huang C, Ma W-Y, Maxiner A, Sun Y, Dong Z. p38 kinase mediates UV-induced phosphorylation of p53 protein at serine 389. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(18):12229–12235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rehfuss RP, Walton KM, Loriaux MM, Goodman RH. The cAMP-regulated enhancer-binding protein ATF-1 activates transcription in response to cAMP-dependent protein kinase A. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266(28):18431–18434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ma Y, Pope RM. The role of macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2005;11(5):569–580. doi: 10.2174/1381612053381927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tesch GH. Role of macrophages in complications of Type 2 diabetes. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 2007;34(10):1016–1019. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nguyen D, Ping F, Mu W, Hill P, Atkins RC, Chadban SJ. Macrophage accumulation in human progressive diabetic nephropathy. Nephrology. 2006;11(3):226–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fukumoto H, Naito Z, Asano G, Aramaki T. Immunohistochemical and morphometric evaluations of coronary atherosclerotic plaques associated with myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 1998;5(1):29–35. doi: 10.5551/jat1994.5.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Said G, Lacroix C, Lozeron P, Ropert A, Planté V, Adams D. Inflammatory vasculopathy in multifocal diabetic neuropathy. Brain. 2003;126, part 2:376–385. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tang S, Scheiffarth OF, Thurau SR, Wildner G. Cells of the immune system and their cytokines in epiretinal membranes and in the vitreous of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmic Research. 1993;25(3):177–185. doi: 10.1159/000267287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Qin B, Xiao B, Liang D, Li Y, Jiang T, Yang H. MicroRNA let-7c inhibits Bcl-xl expression and regulates ox-LDL-induced endothelial apoptosis. BMB Reports. 2012;45(8):464–469. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2012.45.8.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Findlay EG, Hussell T. Macrophage-mediated inflammation and disease: a focus on the lung. Mediators of Inflammation. 2012;2012:6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/140937.140937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chawla A, Nguyen KD, Goh YPS. Macrophage-mediated inflammation in metabolic disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2011;11(11):738–749. doi: 10.1038/nri3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gui T, Shimokado A, Sun YJ, Akasaka T, Muragaki Y. Diverse roles of macrophages in atherosclerosis: from inflammatory biology to biomarker discovery. Mediators of Inflammation. 2012;2012:14 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/693083.693083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grip O, Janciauskiene S, Lindgren S. Macrophages in inflammatory bowel disease. Current Drug Targets. 2003;2(2):155–160. doi: 10.2174/1568010033484179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wynn TA, Barron L. Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2010;30(3):245–257. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang WS, Park YC, Kim JH, et al. Nanostructured, self-assembling peptide K5 blocks TNF- and PGE 2 production by suppression of the AP-1/p38 pathway. Mediators of Inflammation. 2012;2012:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/489810.489810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Byeon SE, Lee J, Yoo BC, et al. P38-Targeted inhibition of interleukin-12 expression by ethanol extract from Cordyceps bassiana in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 2011;33(1):90–96. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2010.482137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Garcia J, Lemercier B, Roman-Roman S, Rawadi G. A Mycoplasma fermentans-derived synthetic lipopeptide induces AP-1 and NF-κB activity and cytokine secretion in macrophages via the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(51):34391–34398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Amirouche A, Tadesse H, Lunde JA, Bélanger G, Côté J, Jasmin BJ. Activation of p38 signaling increases utrophin A expression in skeletal muscle via the RNA-binding protein KSRP and inhibition of AU-rich element-mediated mRNA decay: implications for novel DMD therapeutics. Human Molecular Genetics. 2013;22(15):3093–3111. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pietersma A, Tilly BC, Gaestel M, et al. P38 mitogen activated protein kinase regulates endothelial VCAM-1 expression at the post-transcriptional level. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;230(1):44–48. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.5886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Guma M, Hammaker D, Topolewski K, et al. Antiinflammatory functions of p38 in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis advantages of targeting upstream kinases MKK-3 or MKK-6. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2012;64(9):2887–2895. doi: 10.1002/art.34489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jackson JR, Bolognese B, Hillegass L, et al. Pharmacological effects of SB 220025, a selective inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, in angiogenesis and chronic inflammatory disease models. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;284(2):687–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Brando Lima AC, Machado AL, Simon P, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of LASSBio-998, a new drug candidate designed to be a p38 MAPK inhibitor, in an experimental model of acute lung inflammation. Pharmacological Reports. 2011;63(4):1029–1039. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70619-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Menghini R, Casagrande V, Menini S, et al. TIMP3 overexpression in macrophages protects from insulin resistance, adipose inflammation, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Diabetes. 2012;61(2):454–462. doi: 10.2337/db11-0613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schett G, Zwerina J, Firestein G. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2008;67(7):909–916. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.074278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Langer Lilleholt L, Johansen C, Arthur JSC, et al. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase isoforms in murine skin inflammation induced by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2011;91(3):271–278. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schindler EM, Hindes A, Gribben EL, et al. p38δ mitogen-activated protein kinase is essential for skin tumor development in mice. Cancer Research. 2009;69(11):4648–4655. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kummer JL, Rao PK, Heidenreich KA. Apoptosis induced by withdrawal of trophic factors is mediated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(33):20490–20494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Takenaka K, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. Activation of the protein kinase p38 in the spindle assembly checkpoint and mitotic arrest. Science. 1998;280(5363):599–661. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Morooka T, Nishida E. Requirement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase for neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(38):24285–24288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Engelman JA, Lisanti MP, Scherer PE. Specific inhibitors of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase block 3T3- L1 adipogenesis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;273(48):32111–32120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schindler JF, Monahan JB, Smith WG. P38 pathway kinases as anti-inflammatory drug targets. Journal of Dental Research. 2007;86(9):800–811. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lee JC, Griswold DE, Votta B, Hanna N. Inhibition of monocyte IL-1 production by the anti-inflammatory compound, SK&F 86002. International Journal of Immunopharmacology. 1988;10(7):835–843. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(88)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lee JC, Kassis S, Kumar S, Badger A, Adams JL. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors-mechanisms and therapeutic potentials. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1999;82(2-3):389–397. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gallagher TF, Fier-Thompson SM, Garigipati RS, et al. 2,4,5-triarylimidazole inhibitors of IL-1 biosynthesis. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 1995;5(11):1171–1176. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Saklatvala J. The p38 MAP kinase pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory disease. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2004;4(4):372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nemoto S, Xiang J, Huang S, Lin A. Induction of apoptosis by SB202190 through inhibition of p38β mitogen-activated protein kinase. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(26):16415–16420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lantos I, Bender PE, Razgaitis KA, et al. Antiinflammatory activity of 5,6-diaryl-2,3-dihydroimidazo[2,1-b]thiazoles. Isomeric 4-pyridyl and 4-substituted phenyl derivatives. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1984;27(1):72–75. doi: 10.1021/jm00367a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kim EH, Shim B, Kang S, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Scutellaria baicalensis extract via suppression of immune modulators and MAP kinase signaling molecules. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;126(2):320–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yu T, Ahn HM, Shen T, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of ethanol extract derived from Phaseolus angularis beans. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2011;137(3):1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ma HD, Deng YR, Tian Z, Lian ZX. Traditional Chinese medicine and immune regulation. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2013;44(3):229–241. doi: 10.1007/s12016-012-8332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Amirghofran Z. Medicinal plants as immunosuppressive agents in traditional Iranian medicine. Iranian Journal of Immunology. 2010;7(2):65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Shen ZY. Reviewing and evaluating of the traditional Chinese medicine affecting on immunological function. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 1992;12(7):443–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yang J-X, Wang X-M. Progress in studies on anti-hepatoma effect of traditional Chinese medicine by adjusting immune function. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2007;32(4):281–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. Journal of Natural Products. 2007;70(3):461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Chao K-P, Hua K-F, Hsu H-Y, Su Y-C, Chang S-T. Anti-inflammatory activity of sugiol, a diterpene isolated from Calocedrus formosana bark. Planta Medica. 2005;71(4):300–305. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Cho S-Y, Park S-J, Kwon M-J, et al. Quercetin suppresses proinflammatory cytokines production through MAP kinases and NF-κB pathway in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophage. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2003;243(1-2):153–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1021624520740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wadsworth TL, McDonald TL, Koop DR. Effects of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) and quercetin on lipopolysaccharide-induced signaling pathways involved in the release of tumor necrosis factor-α . Biochemical Pharmacology. 2001;62(7):963–974. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00734-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lee DY, Li H, Lim HJ, Lee HJ, Jeon R, Ryu JH. Anti-inflammatory activity of sulfur-containing compounds from garlic. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2012;15(11):992–999. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2012.2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Munoz L, Ramsay EE, Manetsch M, et al. Novel p38 MAPK inhibitor ML3403 has potent anti-inflammatory activity in airway smooth muscle. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;635(1–3):212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Terajima M, Inoue T, Magari K, Yamazaki H, Higashi Y, Mizuhara H. Anti-inflammatory effect and selectivity profile of AS1940477, a novel and potent p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;698(1–3):455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hill RJ, Dabbagh K, Phippard D, et al. Pamapimod, a novel p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor: preclinical analysis of efficacy and selectivity. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2008;327(3):610–619. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.139006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.MacNee W, Allan RJ, Jones I, de Salvo MC, Tan LF. Efficacy and safety of the oral p38 inhibitor PH-797804 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised clinical trial. Thorax. 2013;68(8):738–745. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lomas DA, Lipson DA, Miller BE, et al. An oral inhibitor of p38 MAP kinase reduces plasma fibrinogen in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2012;52(3):416–424. doi: 10.1177/0091270010397050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Elkhawad M, Rudd JH, Sarov-Blat L, et al. Effects of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition on vascular and systemic inflammation in patients with atherosclerosis. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2012;5(9):911–922. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Soegaard-Madsen L, Johansen C, Iversen L, Kragballe K. Adalimumab therapy rapidly inhibits p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity in lesional psoriatic skin preceding clinical improvement. British Journal of Dermatology. 2010;162(6):1216–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zhang X, Huang Y, Navarro MT, Hisoire G, Caulfield JP. A proof-of-concept and drug-drug interaction study of pamapimod, a novel p38 MAP kinase inhibitor, with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2010;50(9):1031–1038. doi: 10.1177/0091270009357433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Bagley MC, Davis T, Dix MC, et al. Gram-scale synthesis of the p38α MAPK-inhibitor VX-745 for preclinical studies into Werner syndrome. Future Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;2(9):1417–1427. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Liu C, Lin J, Wrobleski ST, et al. Discovery of 4-(5-(Cyclopropylcarbamoyl)-2-methylphenylamino)-5-methyl-N- propylpyrrolo[1,2-f ][1,2,4]triazine-6-carboxamide (BMS-582949), a clinical p38α MAP kinase inhibitor for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;53(18):6629–6639. doi: 10.1021/jm100540x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sarov-Blat L, Morgan JM, Fernandez P, et al. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase reduces inflammation after coronary vascular injury in humans. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2010;30(11):2256–2263. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.209205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Goldstein DM, Kuglstatter A, Lou Y, Soth MJ. Selective p38α inhibitors clinically evaluated for the treatment of chronic inflammatory disorders. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;53(6):2345–2353. doi: 10.1021/jm9012906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sun Y, Li Y-H, Wu X-X, et al. Ethanol extract from Artemisia vestita, a traditional Tibetan medicine, exerts anti-sepsis action through down-regulating the MAPK and NF-κB pathways. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2006;17(5):957–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gayathri B, Manjula N, Vinaykumar KS, Lakshmi BS, Balakrishnan A. Pure compound from Boswellia serrata extract exhibits anti-inflammatory property in human PBMCs and mouse macrophages through inhibition of TNFα, IL-1β, NO and MAP kinases. International Immunopharmacology. 2007;7(4):473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Kao E-S, Hsu J-D, Wang C-J, Yang S-H, Cheng S-Y, Lee H-J. Polyphenols extracted from Hibiscus sabdariffa L. inhibited lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation by improving antioxidative conditions and regulating cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 2009;73(2):385–390. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Burk DR, Senechal-Willis P, Lopez LC, Hogue BG, Daskalova SM. Suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages by aqueous extract of Clinopodium vulgare L. (Lamiaceae) Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;126(3):397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Uto T, Suangkaew N, Morinaga O, Kariyazono H, Oiso S, Shoyama Y. Eriobotryae folium extract suppresses LPS-induced iNOS and COX-2 expression by inhibition of NF-κB and MAPK activation in murine macrophages. American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2010;38(5):985–994. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X10008408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Kwon O-K, Ahn K-S, Park J-W, et al. Ethanol extract of Elaeocarpus petiolatus inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in macrophage cells. Inflammation. 2012;35(2):535–544. doi: 10.1007/s10753-011-9343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Seo H-J, Huh J-E, Han J-H, et al. Polygoni rhizoma inhibits inflammatory response through inactivation of nuclear factor-kappaB and mitogen activated protein kinase signaling pathways in RAW264.7 mouse macrophage cells. Phytotherapy Research. 2012;26(2):239–245. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Jang S-H, Lee EK, Lim MJ, et al. Suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of inflammatory indicators in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells by extract prepared from Ginkgo biloba cambial meristematic cells. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2012;50(4):420–428. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2011.610805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Oh Y-C, Cho W-K, Im GY, et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of Lycium Fruit water extract in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. International Immunopharmacology. 2012;13(2):181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Yang Y, Yu T, Lee YG, et al. Methanol extract of Hopea odorata suppresses inflammatory responses via the direct inhibition of multiple kinases. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2013;145(2):598–607. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Chao LK, Hua KF, Hsu HY, Su YC, Chang ST. Bioactivity assay of extracts from Calocedrus macrolepis var. formosana bark. Bioresource Technology. 2006;97(18):2462–2465. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Ahn J-Y, Choi I-S, Shim J-Y, et al. The immunomodulator ginsan induces resistance to experimental sepsis by inhibiting Toll-like receptor-mediated inflammatory signals. European Journal of Immunology. 2006;36(1):37–45. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Zhou HY, Shin EM, Guo LY, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of 4-methoxyhonokiol is a function of the inhibition of iNOS and COX-2 expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages via NF-κB, JNK and p38 MAPK inactivation. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;586(1–3):340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Guo LY, Hung TM, Bae KH, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of schisandrin isolated from the fruit of Schisandra chinensis Baill. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;591(1–3):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Kim JH, Kim DH, Baek SH, et al. Rengyolone inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide production by down-regulation of NF-κB and p38 MAP kinase activity in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2006;71(8):1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Yun K-J, Shin J-S, Choi J-H, Back N-I, Chung H-G, Lee K-T. Quaternary alkaloid, pseudocoptisine isolated from tubers of Corydalis turtschaninovi inhibits LPS-induced nitric oxide, PGE2, and pro-inflammatory cytokines production via the down-regulation of NF-κB in RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cells. International Immunopharmacology. 2009;9(11):1323–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Chen Q, Chen TH, Li WJ, et al. Mycoepoxydiene inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses through the of TRAF6 polyubiquitination. PLOS ONE. 2012;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044890.e44890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Park HH, Kim MJ, Li Y, et al. Britanin suppresses LPS-induced nitric oxide, PGE(2) and cytokine production via NF-kappa B and MAPK inactivation in RAW 264.7 cells. International Immunopharmacology. 2013;15(2):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Lee S, Park H-S, Notsu Y, et al. Effects of hyperin, isoquercitrin and quercetin on lipopolysaccharide- induced nitrite production in rat peritoneal macrophages. Phytotherapy Research. 2008;22(11):1552–1556. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Huang S-C, Ho C-T, Lin-Shiau S-Y, Lin J-K. Carnosol inhibits the invasion of B16/F10 mouse melanoma cells by suppressing metalloproteinase-9 through down-regulating nuclear factor-kappaB and c-Jun. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2005;69(2):221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]