Abstract

Background

Pulmonary vascular function is impaired with increased pulmonary blood flow (PBF). We hypothesized that a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ) agonist would mitigate this effect.

Methods

An aorta to pulmonary artery shunt was placed in 11 fetal lambs. Lambs received the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone (RG, 3 mg/kg/day, n=6) or vehicle (n=5) for 4-weeks. Lung tissue from 5 normal 4-week lambs was used for comparisons.

Results

At 4-weeks, pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) and vascular resistance (PVR) decreased with inhaled NO in RG and vehicle-treated shunt lambs. PAP and PVR decreased with acetylcholine in RG-treated, not vehicle-treated shunt lambs. In vehicle-treated shunt lambs, NADPH oxidase activity, rac1, superoxide, and 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) levels were increased and Ser1177 endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) protein was decreased compared to normal lambs. In RG-treated shunt lambs, NOX, Ser1177 eNOS protein and eNOS activity were increased, and NADPH activity, rac1, superoxide levels and 3-NT levels were decreased, compared to vehicle-treated shunt lambs. PPARγ protein expression was lower in vehicle-treated shunt lambs than normal and RG-treated shunt lambs.

Conclusions

The PPARγ agonist, RG, prevents the loss of agonist induced endothelium-dependent pulmonary vascular relaxation in lambs with increased PBF, in part, due to decreased oxidative stress and/or increased NO production.

Introduction

Infants and children with congenital cardiac defects that cause increased pulmonary blood flow are at risk for developing pulmonary vascular disease. In fact, even early pulmonary vascular dysfunction, with abnormal vascular reactivity, causes significant morbidity and mortality in these patients. A decrease in bioavailable NO, in part due to oxidative stress, is known to contribute to this pathology (1-3).

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), members of a nuclear hormone receptor superfamily, are rapidly emerging as integral mediators of a wide array of disease processes, including vascular disorders (4). Although investigations of the vasculature have focused primarily on the systemic circulation, one study found that PPAR gamma (PPARγ), one of the three PPAR subclasses, was decreased in lung tissue taken from patients with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension (5). The mechanisms by which PPARγ may affect the development of pulmonary vascular disease are not fully understood. However, expanding data indicate that the loss of PPARγ may result in perturbations of a number of factors that affect the pulmonary vasculature (6). For example, in recent studies PPARγ ligands have been shown to increase NO production by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), in part by increasing eNOS activity by a promotion of eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177, and decrease reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, through alterations of NADPH oxidase (7-11).

In prior studies, we investigated alterations in NO and ROS production in the development of pulmonary vascular disease under conditions of increased pulmonary blood flow, using our ovine model of a congenital cardiac defect with increased pulmonary blood flow, created by the in utero placement of an aortopulmonary vascular graft (shunt) (1-3). In the post-natal period, these shunt lambs demonstrated impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation, which was associated with a decrease in bioavailable NO, increased NADPH oxidase subunit expression, increased superoxide production, and increased protein nitration (1-3). More recently, we found that PPARγ protein expression was decreased in lung tissue taken from 2-week shunt lambs compared to healthy age-matched controls, raising the possibility that impaired PPARγ signaling could contribute to the observed alterations in pulmonary vascular function and NO signaling (12).

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that chronic treatment with the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone (RG) would preserve endothelium-dependent pulmonary vascular relaxation, increase bioavailable NO, and decrease markers of oxidative stress in lambs with increased pulmonary blood flow. To this end, shunt lambs were treated from birth until 4-weeks of age with enteral RG or vehicle control. At 4-weeks of age, pulmonary vascular responses to acetylcholine (ACh), an endothelium-dependent vasodilator, and inhaled NO, an endothelium-independent vasodilator, were determined, and lung tissue was harvested for determinations of bioavailable NO (NOX levels), eNOS protein expression and activity, eNOS Ser1177 phosphorylation, NADPH subunit expression (Rho-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate (Rac1), p47phox (phagocytic oxidase), p67phox) and activity, superoxide levels, and nitrotyrosine (3-NT), an indirect measure of peroxynitrite.

Results

There were no differences in gestational age, weight, or sex distribution, between normal and vehicle- and RG-treated shunt lambs (data not shown). Likewise, baseline hemodynamic variables were not different between vehicle- and RG-treated shunt lambs (Table 1). Baseline hemodynamics and pulmonary vascular reactivity with comparisons between normal and shunt lambs at 4 weeks of age have been previously reported (1).

Table 1. Baseline Hemodynamics.

| HR (beats/min) | mPAP (mmHg) | Syst SAP (mmHg) | Diast SAP (mmHg) | mSAP (mmHg) | Q (LPA) ml/min/kg | RAP (mmHg) | LAP (mmHg) | Qp:Qs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 155.8±27.1 | 25.0±3.7 | 123.0±18.0 | 32.1±7.9 | 60.8±6.4 | 165.5±51.7 | 5.4±1.3 | 8.5±2.6 | 2.74±0.6 |

| RG-treated | 124±24 | 23.8±7.4 | 115.7±17 | 41.9±9.2 | 62.6±7.4 | 128.2±41.1 | 5.7±1.3 | 6.7±1.8 | 2.8±0.8 |

RG, rosiglitazone; HR, heart rate; mPAP, mean pulmonary artery pressure; Syst SAP, systolic systemic arterial pressure; Diast SAP, diastolic systemic arterial pressure; mSAP, mean systemic arterial pressure; Q, flow; LPA, left pulmonary artery; RAP, right atrial pressure; LAP, left atrial pressure; Qp:Qs, ratio of pulmonary to systemic flow.

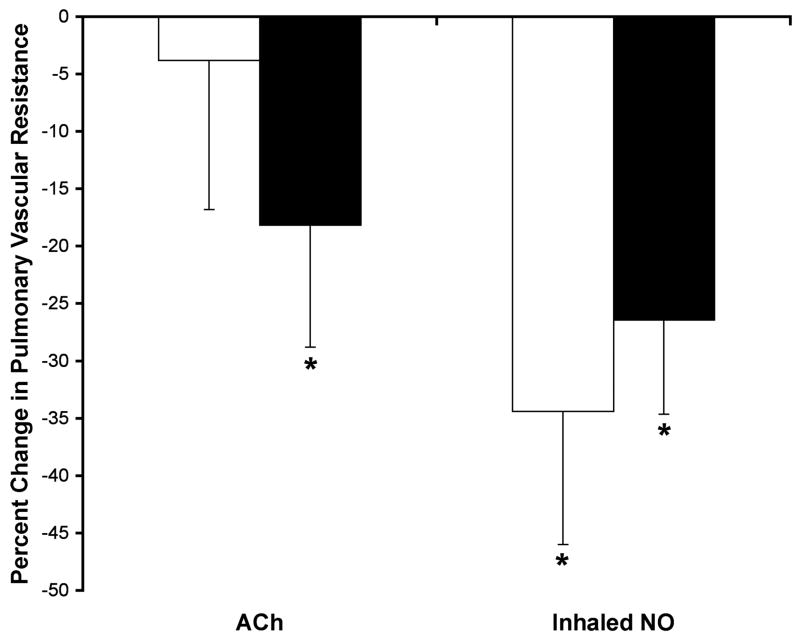

Pulmonary vascular reactivity

Hemodynamic changes in response to ACh and inhaled NO in vehicle- and RG- treated shunt lambs are shown in Table 2. Pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) and calculated PVR did not change in response to ACh in vehicle-treated shunt lambs (Table 2 and Figure 1). In contrast, PAP and calculated PVR decreased in response to ACh in RG-treated shunt lambs (-18.6±5.4% and -18.2±7.3%, respectively, P<0.05, Table 2 and Figure 1). In response to inhaled NO, PAP and calculated PVR decreased in both vehicle-treated (-19.3±6.3% and -34.4±11.6%, respectively, P<0.05) and RG-treated shunt lambs (-16.1±4.2% and -26.4±8.2%, respectively, P<0.05, Table 2 and Figure 1). Changes in PVR in vehicle- and RG-treated shunt lambs in response to ACh and inhaled NO are shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Hemodynamic changes in response to acetylcholine and inhaled nitric oxide.

| Baseline | Ach (1μg/kg) | Baseline | iNO (40ppm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle-Treated Lambs | ||||

| Mean PAP (mmHg) | 25.0±3.7 | 21.9±3.5 | 25.4±3.9 | 20.3±1.8* |

| LPBF (ml/min/kg) | 165.5±51.7 | 156.4±39.5 | 171.3±54.9 | 178.5±55.8 |

| LAP (mmHg) | 9.5±2.6 | 8.0±1.1 | 9.7±2.5 | 9.6±2.6 |

| RAP (mmHg) | 5.4±1.3 | 6.0±1.5 | 5.4±1.4 | 4.9±1.4 |

| HR (beats/min) | 155.8±27.1 | 141.6±23.4 | 155.3±26.7 | 149.6±23.7 |

| Rosiglitazone-Treated Lambs | ||||

| Mean PAP (mmHg) | 23.8±7.4 | 19.4±6.6* | 24.5±7.2 | 20.5±6.0* |

| LPBF (ml/min/kg) | 136.0±37.5 | 128.2±41.1 | 138.8±32.1 | 144.5±31.0 |

| LAP (mmHg) | 6.7±1.8 | 6.5±1.0 | 6.8±3.7 | 6.4±3.5 |

| RAP (mmHg) | 5.0±1.3 | 5.7±1.3 | 5.1±1.4 | 4.9±1.4 |

| HR (beats/min) | 124.1±24 | 119.1±11.1 | 125.7±21.3 | 123.3±24.2 |

Hemodynamic values before (baseline) and after the administration of acetylcholine (ACh) and inhaled nitric oxide (iNO). PAP, pulmonary arterial pressure; LPBF, left pulmonary artery blood flow; LAP, left atrial pressure; RAP, right atrial pressure; HR, heart rate. Values are mean±SD.

P<0.05 compared to baseline value.

Figure 1.

Changes in pulmonary vascular resistance, expressed as percent change from baseline, in response to acetylcholine (ACh, 1 μg/kg), an endothelium-dependent agent, and inhaled nitric oxide (NO, 40 ppm), an endothelium-independent agent in vehicle- and RG-treated shunt lambs. In vehicle-treated shunt lambs (white bars), pulmonary vascular resistance decreased in response to inhaled NO, but not to ACh. In RG-treated shunt lambs (black bars), pulmonary vascular resistance decreased in response to both ACh and inhaled NO. N=6 for RG-treated group. N=5 for vehicle-treated group. Values are mean ± SD. *P<0.05 compared to baseline.

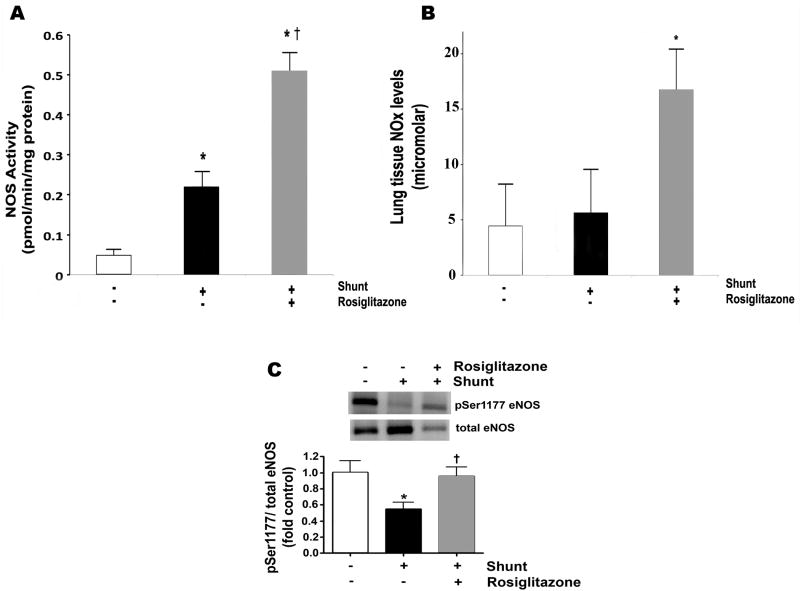

Lung tissue NOS activity, NOx, eNOS protein and Ser117 phosphorylation

Lung tissue NOS activity is shown in Figure 2A. Lung tissue NOS activity was greater in RG-treated shunt lambs than vehicle-treated shunt lambs and both were greater than normal lambs (0.51±.28 vs 0.22±.08 vs 0.05±0.03 ρmol/min/mg protein, p<0.05). Lung tissue NOx levels were greater in RG-treated shunt lambs than vehicle-treated shunt lambs and normal lambs (16.9±8.9 μM vs 5.7±3.0 vs 4.5±3.3 μM, respectively, P<0.05, Figure 2B). NOX levels relative to NOS activity (NOx/NOS activity ratio) were greater in normal lambs than vehicle-treated and RG-treated shunt lambs (p<0.05). Lung tissue eNOS protein levels determined by Western blot analysis were not different between groups (data not shown). eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 is shown in Figure 2C. eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 was lower in vehicle-treated shunt lambs than normal lambs and RG-treated shunt lambs (p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Lung tissue NOS activity, NOx levels and Ser1177 eNOS protein in normal (white bars) and vehicle (black bars)- and RG-treated (gray bars) shunt lambs. (A) NOS activity was greater in vehicle-treated shunt lambs than normal lambs, and greater in RG-treated shunt lambs than both normal lambs and vehicle-treated shunt lambs. (B) Lung tissue NOx levels were higher in RG-treated shunt lambs than normal lambs and vehicle-treated shunt lambs. (C) Lung tissue protein expression of Ser1177 eNOS was decreased in vehicle-treated shunt lambs compared to normal lambs and increased in RG-treated shunt lambs compared to vehicle-treated shunt lambs. Representative Western blots are shown. Densitometric values for Ser1177 eNOS protein are shown relative to normal. N=5 for normal group. N=5 for vehicle-treated shunt group N=6 for RG-treated shunt group. Values are mean ± SD. *P<0.05 compared to normal group. †P<0.05 compared to vehicle-treated shunt group.

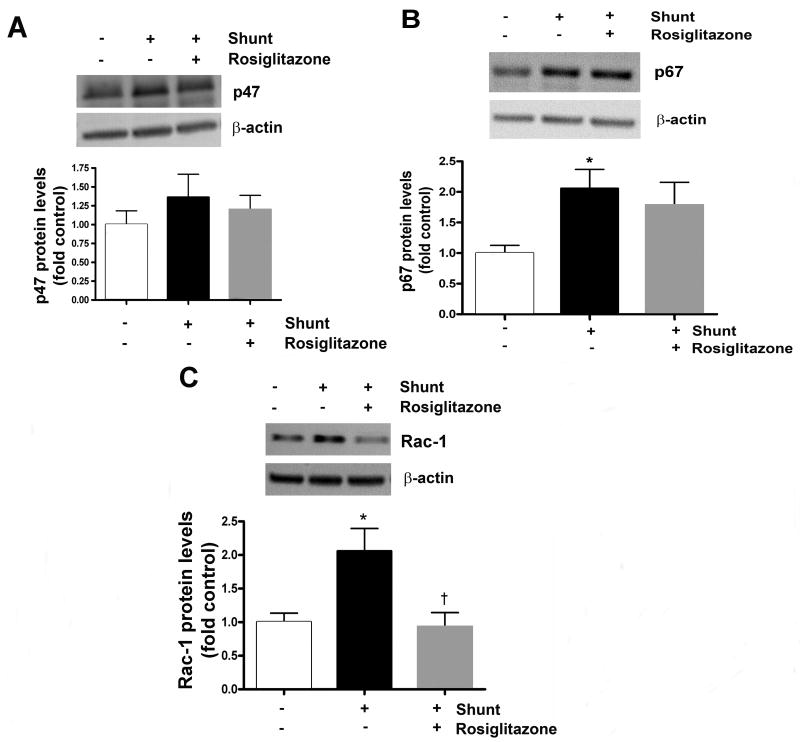

NADPH oxidase subunit expression

Lung tissue protein levels of p47phox, p67phox, and Rac 1 in normal and vehicle- and RG-treated shunt lambs are shown in Figure 3 (A-C). Lung tissue protein expression of p47phox was ∼ 20% greater and p67phox was 2-fold greater in vehicle-treated shunt lambs than normal lambs, but differences between groups failed to reach statistical significance between groups (ANOVA, p=0.08, Figure 3A and 3B). Lung tissue protein expression of rac-1 was 2-fold greater in vehicle-treated shunt lambs than normal lambs, and levels were similar between normal lambs and RG-treated shunt lambs (Figure 3C, ANOVA, p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Lung tissue protein levels of NADPH oxidase subunits p47phox (A), p67phox (B), and rac1 (C) in normal (white bars) and vehicle (black bars)- and RG-treated (gray bars) shunt lambs. (A and B) Differences between lung tissue protein expression of p47phox and p67phox (ANOVA, P=0.08) did not reach statistical significance. (C) Lung tissue protein expression of rac-1 was greater in vehicle-treated shunt lambs than normal lambs, and was lower in RG-treated compared to vehicle-treated shunt lambs (ANOVA, P<0.05). Representative Western blots are shown. Densitometric values shown relative to normal. N=5 for normal group. N=5 for vehicle-treated shunt group N=6 for RG-treated shunt group. Values are mean ± SD. *P<0.05 compared to normal group. †P<0.05 compared to vehicle-treated shunt group.

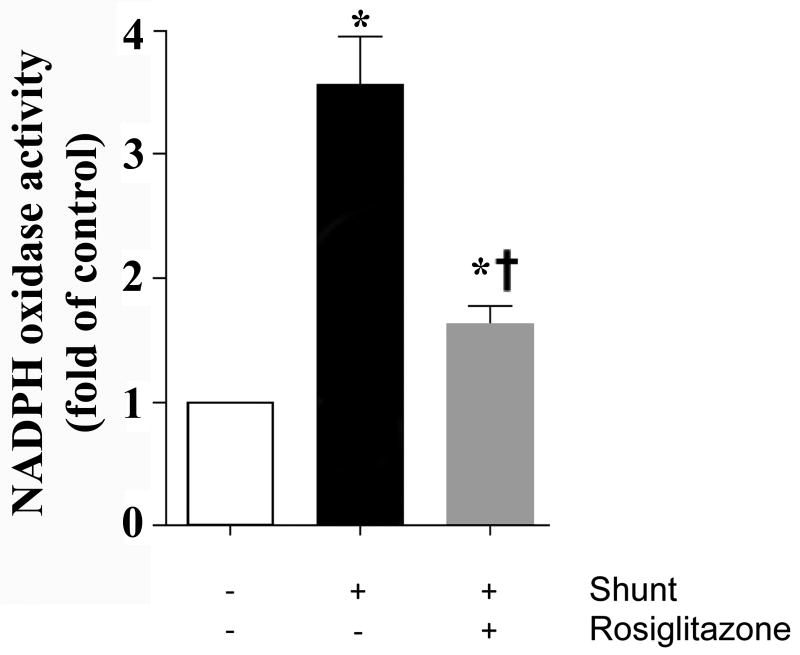

NADPH oxidase activity

NADPH oxidase activity in lung tissue was higher in vehicle-treated shunt lambs than normal lambs and RG-treated shunt lambs (Figure 4, ANOVA, p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Lung tissue NADPH oxidase activity in normal (white bars) and vehicle (black bars)- and RG-treated (gray bars) shunt lambs. Lung tissue NADPH oxidase activity was measured by a low concentration based lucigenin (5 μM) assay. Control activity was arbitrarily set at 100%. n=4 for each group. Values are mean ± S.D. *P<0.05, compared to normal group. †P<0.05 compared to vehicle-treated shunt group.

Superoxide Quantitation

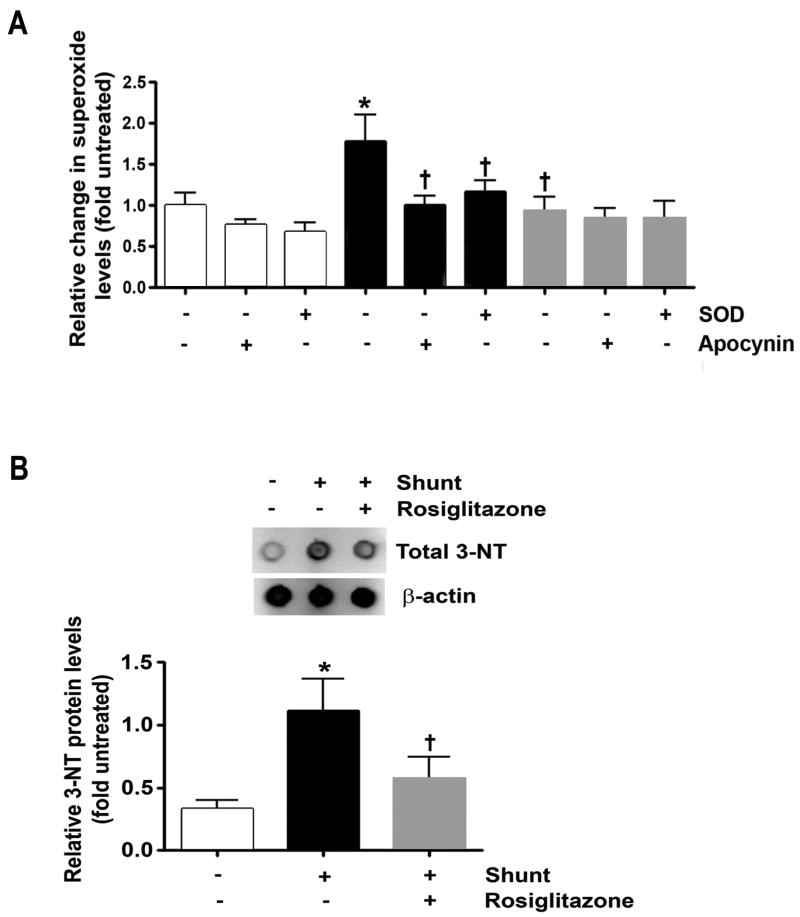

Relative superoxide levels, determined by EPR on peripheral lung taken from normal lambs and vehicle- and RG-treated shunt lambs, are shown in Figure 5. Superoxide levels were ∼ 1.75 fold greater in vehicle-treated shunt lambs than normal lambs (Figure 6A, ANOVA, p<0.05). Superoxide levels were not different between normal lambs and RG-treated shunt lambs (Figure 6A). Specificity of the EPR assay for superoxide was confirmed by a significant reduction in the waveform amplitude in vehicle-treated lambs with the addition of superoxide dismutase (SOD) to the samples (13). To determine to what extent the contribution of superoxide production arose from NADPH oxidase activity, samples were incubated with apocynin (an NADPH oxidase inhibitor) for 30 minutes on ice prior to the addition of CMH. Apocynin-mediated inhibition of NADPH resulted in almost no change in EPR amplitude of normal lambs and RG-treated shunt lambs, while vehicle-treated shunt lambs showed up to ∼37% reduction in signal (Figure 6A, P<0.05).

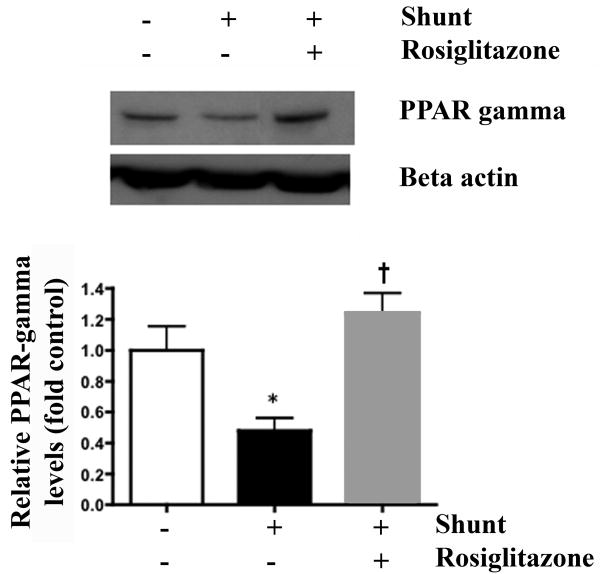

Figure 5.

Lung tissue protein expression of PPARγ in normal (white bars) and vehicle (black bars)- and rosiglitazone (RG)-treated (gray bars) shunt lambs. PPARγ was decreased in vehicle-treated shunt lambs compared to normal lambs and increased in RG-treated shunt lambs compared to vehicle-treated shunt lambs. Representative Western blots are shown. Densitometric values for PPARγ protein are shown relative to normal. N=5 for normal group. N=5 for vehicle-treated shunt group N=6 for RG-treated shunt group. Values are mean ± SD. *P<0.05 compared to normal group. †P<0.05 compared to vehicle-treated shunt group.

Figure 6.

Superoxide (A) and nitrotyrosine (3-NT) protein levels (B) in lung tissue from normal (white bars) and vehicle (black bars)- and RG-treated (gray bars) shunt lambs. (A) Superoxide levels estimated by electron paramagnetic resonance. Superoxide levels where higher in vehicle-treated shunt lambs than normal lambs, and lower in RG-treated than vehicle-treated lambs. Specificity of the EPR assay for superoxide was confirmed by a reduction in the waveform amplitude with the addition of superoxide dismutase (SOD) to the samples, in vehicle-treated shunt lambs. The addition of apocynin (an NADPH oxidase inhibitor) to the samples resulted in no change in EPR amplitude of normal and RG-treated lambs, but a ∼37% signal reduction in vehicle-treated lambs. (B) Lung tissue 3-NT levels were increased in vehicle-treated shunt lambs compared to normal lambs, and decreased in RG-treated compared to vehicle-treated shunt lambs. Representative Western blots are shown. N=5 for normal group. N=5 for vehicle-treated shunt group N=6 for RG-treated shunt group. Values are mean ± SD. *P<0.05 compared to normal group. †P<0.05 compared to vehicle-treated shunt group.

Protein nitration

As an indirect determination of peroxynitrite formation, lung tissue nitrotyrosine (3-NT) levels were determined, and are shown in Figure 6B. Lung tissue 3-NT protein expression was greater in vehicle-treated shunt lambs than normal lambs and RG-treated shunt lambs (Figure 6B, ANOVA, p<0.05).

PPARγ protein expression

Lung tissue PPAR-gamma protein levels in vehicle-treated shunt lambs were lower than control lambs and RG-treated shunt lambs (Figure 5, ANOVA, p<0.05).

Discussion

A vast and expanding body of literature has established the importance of endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of pulmonary vascular disease. Endothelial abnormalities, however, are defined broadly. They include: alterations in structure, perturbations in the normal production and/or balance of endothelial-derived factors, and functional abnormalities, including increased constriction and/or impaired relaxation. The present study used a model of a congenital cardiac defect with increased pulmonary blood flow, that mimics the early functional impairment in pulmonary vascular endothelium-dependent relaxation that occurs in infants and children with large left-to-right cardiac shunts, before the development of advanced structural changes and large elevations in PAP. Indeed, in the current era where surgical repair in neonates and infants is relatively safe and common, it is these early derangements that account for a substantial portion of the morbidity rather than advanced structural disease that occurred in previous decades. The primary finding was that chronic treatment with RG prevented impairment in agonist-induced endothelium-dependent pulmonary vascular relaxation in shunt lambs. The association of this finding with an increase in lung tissue NOx levels, increased eNOS activity, increased eNOS phosphorylation (Ser1177), decreased NADPH oxidase activity and subunit expression, and decreased lung tissue superoxide and 3-NT levels suggests two potential mechanisms for this effect: (1) PPARγ activation may increase bioavailable NO through a decrease in NADPH oxidase activity that results in a decrease in NO scavenging by superoxide; and (2) PPARγ activation may increase NO production from eNOS, by increasing eNOS activity via increased phosphorylation at Ser1177.

In vitro and in vivo studies indicate that PPARγ signaling can alter oxidative stress and that RG treatment can decrease superoxide production in the systemic vasculature (9-11,14). In the pulmonary vasculature, RG treatment was shown to attenuate pulmonary arterial hypertension and vascular remodeling in chronic-hypoxia mouse models. Mechanisms include alterations in NADPH subunit expression, superoxide levels, regulation of Nox4 expression through NF-kappaB, and a down regulation of PPARγ through transforming growth factor-beta (15-17). Thus, the findings of the present study are consistent with this emerging literature, but are unique in demonstrating a role for PPARγ in early selective pulmonary vascular endothelial dysfunction secondary to increased pulmonary blood flow.

In the present study, a role for NADPH oxidase is supported by changes in its activity and a decrease in superoxide signaling in the EPR assay with apocynin (an NADPH oxidase inhibitor) in vehicle-treated shunt lambs. Interestingly, rac-1 protein levels normalized in RG-treated shunt lambs and apocynin had no impact on superoxide levels. While these data strongly implicate PPARγ signaling in increased NADPH activity under conditions of increased pulmonary blood flow, the controlling mechanisms require further investigation.

Lung tissue eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 decreased in vehicle-treated lambs compared to normal lambs and normalized in shunt lambs with RG-treatment, in association with a significant increase in eNOS activity. Phosphorylation at Ser1177 is known to increase electron flux and enzyme activity of eNOS (18,19). Therefore, the increased lung tissue NOX levels, that were independent of changes in eNOS expression, in RG-treated shunt lambs may relate, in part, to an increase in NO release from endothelial cells apart from, or in addition to, diminished scavenging of NO by superoxide. Pulmonary blood flow (with its associated shear forces) is a well-established and strong stimulus of NO release from eNOS (20). Therefore, the increase in NOX and eNOS activity in shunt lambs compared to normal lambs was expected and consistent with previous studies (1). Alterations in bioavailable NO cannot be simply understood by analysis of lung tissue NOX levels. Rather, the demonstration of impaired agonist-induced selective endothelium-dependent pulmonary relaxation is of primary relevance. However, we have previously demonstrated that impaired bioavailable NO can be understood by analyzing NOX levels relative to eNOS activity. We have shown previously that shunt lambs develop a progressive decrease in NOX levels relative to eNOS activity when compared to age-matched normal lambs from 2 to 8 weeks of age (1). In the present study, as expected NOS activity was increased in shunt lambs compared to normal lambs, and NOX levels relative to eNOS activity were greater in normal lambs compared to shunt lambs. Interestingly, RG-treatment resulted in a marked increase in NOX and eNOS activity in shunt lambs.

Superoxide reacts avidly with NO to produce peroxynitrite. The determination of peroxynitrite levels in vivo is challenging. Peroxynitrite readily nitrates protein tyrosine residues, and thus quantification of nitrotyrosine (3-NT) provides an indirect measure of peroxynitrite levels. Consistent with previous studies, we found an increase in 3-NT levels in vehicle-treated shunt lambs compared to normal lambs. Moreover, consistent with our hypothesis that RG-treatment would decrease oxidative stress in shunt lambs, we found the RG-treated shunt lambs had 3-NT levels that were lower than vehicle-treated shunt lambs and similar to normal lambs.

Interestingly, we found that PPARγ expression was decreased in vehicle-treated shunt lambs compared to normal lambs, and increased in RG-treated shunt lambs. Little is known about the regulation of PPARγ expression in lung tissue in either health or disease. A recent study demonstrated that NO can activate PPARγ via a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, which is intriguing given the increased NOX levels in RG-treated shunt lambs (21). However, whether cross-talk between NO and PPARγ results in increased PPARγ expression in lung tissue is unclear. In addition, whether PPARγ activation, from RG-treatment, alone accounted for the preservation in endothelium-dependent pulmonary vascular relaxation or whether the increase in PPARγ expression was necessary remains an interesting but unanswered question.

We conclude that PPARγ activation with chronic RG treatment attenuates the impairment in agonist induced endothelium-dependent pulmonary vascular relaxation in 4-week old lambs with a model of increased pulmonary blood flow. We propose that an increase in bioavailable NO underlies this effect, and that it may be mediated by two potential mechanisms: (1) a decrease in NADPH oxidase activity that results in lower superoxide levels with less NO scavenging; and (2) an increase in NO production secondary to increased eNOS activity due to increased phosphorylation at Ser1177. The potential ability to use PPARγ agonists to diminish endothelial injury and/or dysfunction in infants and children with common congenital cardiac defects that result in increased pulmonary blood flow is exciting since this class of medications is currently commercially available for clinical use. Therefore, we believe that further investigation of these pathways is warranted.

Methods

Surgical Preparation

11 mixed-breed Western pregnant ewes (137-141 days gestation, term = 145 days) were anesthetized. Fetal exposure was obtained through the pregnant horn of the uterus and a left lateral thoracotomy was performed on the fetal lamb. With the use of side biting vascular clamps an 8.0 mm vascular graft was anastomosed between the ascending aorta and main pulmonary artery of the fetal lambs. This procedure was previously described in detail (1).

Four weeks after spontaneous delivery, shunt lambs were anesthetized and catheters were placed into the right and left atrium, and main pulmonary artery. An ultrasonic flow probe (Transonics Systems, Ithaca, NY) was placed around the left pulmonary artery to measure pulmonary blood flow. Arterial blood and lung biopsies were obtained. In addition, using identical anesthesia, arterial blood and lung tissue was harvested from 5 normal, non-shunted, 4-week old lambs for comparisons of biochemical data to vehicle- and RG-treated shunt lambs. Arterial blood and lung pieces were processed as previously described in detail (1).

At the end of the protocol, all lambs were killed with a lethal injection of sodium pentobarbital followed by bilateral thoracotomy as described in the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All protocols and procedures were approved by the Committee on Animal Research of the University of California, San Francisco.

Drug Protocol

Beginning immediately after birth, lambs were treated with either RG (GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, United Kingdom, n=6, 3mg/kg/day) or empty gelatin capsules (n=5, vehicle control). The drug or vehicle capsules were administered once daily by mouth for a 4-week period. The number of vehicle capsules administered was increased to match the upwardly adjusted weight-based dosing of RG.

Measurements

Pulmonary and systemic arterial, and right and left atrial pressures, heart rate and pulmonary blood flow were measured. All hemodynamic variables were measured continuously utilizing the Gould Ponemah Physiology Platform (Version 4.2) and Acquisition Interface (Model ACG-16, Gould Inc., Cleveland, OH). Blood gases and pH were measured and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was calculated using standard formulas. Shunt fraction (Qp/Qs) was determined using the Fick principle. These procedures were previously described in detail (1).

Pulmonary Vascular Reactivity

Pulmonary vascular responses were assessed after the administration of ACh and inhaled NO. Lambs were instrumented as above and allowed to rest for a minimum of 30 minutes. Mechanical ventilation was adjusted to maintain pCO2 between 35 and 40 mm Hg and pH between 7.35 and 7.40. Sodium bicarbonate was administered to correct metabolic acidosis if it occurred. The inspired oxygen concentration was maintained at 21%. Baseline hemodynamics and pulmonary blood flow were recorded. In random order, ACh (1μg/kg) or inhaled NO (40 ppm) was administered. Acetylcholine chloride (Iolab, Claremont, CA) was diluted in sterile 0.9% saline and delivered by rapid injection into the pulmonary artery. Inhaled NO was delivered to the inspiratory limb of the respiratory circuit (Inovent, Ohmeda Inc., Liberty, N.J.), and continued for 10 minutes. The inspired concentrations of NO and nitrogen dioxide were continuously quantified by electrochemical methodology (Inovent, Ohmeda Inc., Liberty, N.J.). The hemodynamic variables were monitored and recorded continuously. A minimum of 30 minutes separated the administration of ACh and inhaled NO, and the second agent was not given until baseline hemodynamics returned.

Preparation of Protein Extracts and Western Blot Analysis

Lung protein extracts were prepared and Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (1,22). Briefly, Western blot analysis was performed with a 1:2500 dilution of the NOS antiserum, 1:100 dilution of PPARγ, 1:500 dilution of Rac1, p47phox, and p67phox, 1:1000 dilution of 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) antibody and anti-phospho Ser1177 eNOS, or a 1:10,000 dilution of β-actin, washed with tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween, and then incubated with a goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase. After washing, the protein bands were visualized with chemiluminescence using a Kodak Digital Science Image Station (NEN) and analyzed using the KED-1 software. All captured and analyzed images were determined to be in the dynamic range of the system. The eNOS, Rac1, p47phox and PPARγ, antiserum was obtained from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY), 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) antibody was obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA), and anti-phospho Ser1177 eNOS was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). To normalize for protein loading, blots were re-probed with β-actin.

Measurement of NOx

To quantify bioavailable NO, NO and its metabolites were determined in lung tissue, as we have previously described (1,23,24). The sensitivity is 1 × 10-12 moles, with a concentration range of 1 × 10-9 to 1 × 10-3 molar of nitrate.

Assay for NOS activity

NOS activity was determined using the conversion of 3H-L-arginine to 3H-L-citrulline as described by Bush (25) and as we have previously described in detail (1). All activities were normalized to the amount of protein in each lysate. To determine the potential contribution of inducible NOS (iNOS) to total NOS activity, assays were repeated without calcium supplementation.

Lung tissue NADPH Oxidase Assay

Lung tissue from normal lambs and vehicle- and RG-treated shunt lambs was collected and homogenated with Tris-sucrose buffer (10mM Trise base (Fischer, Fairlawn NJ), 340mM sucrose (Mallinkrodt Baker, Inc., Philipsburg, NJ), 1mM EDTA (Mallinkrodt Baker), and 10ug/ml protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The homogenate protein concentration was measured. NADPH oxidase activity was maeasured by a luminescence assay in the reaction buffer with 5μM Lucigenin, 1mM EGTA and 50mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. 100μg of homogenate protein + 100μM NADPH as substrate (Sigma) were added to 8mm test tube with 500 μl reaction buffer, then incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Photon emission was measured at 15 seconds in a luminometer (model TD-20/20, Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA) (26,27).

Superoxide Quantitation

Superoxide levels in lung tissue were estimated by electronic paramagnetic resonance (EPR) assay using the spin-trap compound 1-hydroxy-3-methoxycarbonyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidine·HCl (CMH) in the presence and absence of polyethylene glycol-superoxide dismutase, as we have previously described (1,13). To determine the specificity of detected EPR signal, additional sample groups were immersed in EPR Buffer supplemented with 100 U/ml membrane permeable form of SOD (polyethylene glycol-conjugated superoxide dismutase, PEG-SOD). In addition, in order to determine the relative contribution of NADPH oxidase activity to superoxide production, equivalent samples were pre-incubated in 100 µM apocynin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), an NADPH oxidase inhibitor, as we have previously described (1,28). Samples were analyzed for protein content using Bradford analysis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Sample volumes were then adjusted with EPR Buffer and 25 mg/ml CMH hydrochloride in order to achieve equal protein content and a final CMH concentration of 5 mg/ml. Samples were analyzed with a MiniScope MS200 ESR (Magnettech, Berlin, Germany). Resulting EPR spectra were analyzed using ANALYSIS v.2.02 software (Magnettech, Berlin, Germany), whereby the EPR maximum and minimum spectral amplitudes for the CM• superoxide spin-trap product waveform were quantified.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical calculations were performed using the GraphPad Prism V. 4.01 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The mean ± SD or SE was calculated for all samples, and significance was determined either by the unpaired t-test or ANOVA. For ANOVA Newman Keuls post hoc testing was also utilized.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Michael Johengen and Cynthia Harmon for their expert technical assistance.

Statement of financial support: This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants HD047349 (to PO), HL60190 (to SMB), HL67841 (to SMB), HL72123 (to SMB), HL70061 (to SMB), HL084739-03 (to SMB), HD057406 (to SMB), and HL61284 (to JRF) and a Transatlantic Network Development grant from the LeDucq Foundation (to SMB and JRF).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose with respect to any financial ties to products in the study of potential/perceived conflicts of interest.

[Category of Study: Translational]

References

- 1.Oishi PE, Wiseman DA, Sharma S, et al. Progressive dysfunction of nitric oxide synthase in a lamb model of chronically increased pulmonary blood flow: a role for oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L756–66. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00146.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakshminrusimha S, Wiseman D, Black SM, et al. The role of nitric oxide synthase-derived reactive oxygen species in the altered relaxation of pulmonary arteries from lambs with increased pulmonary blood flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1491–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00185.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grobe AC, Wells SM, Benavidez E, et al. Increased oxidative stress in lambs with increased pulmonary blood flow and pulmonary hypertension: role of NADPH oxidase and endothelial NO synthase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L1069–77. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00408.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kersten S, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Roles of PPARs in health and disease. Nature. 2000;405:421–4. doi: 10.1038/35013000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ameshima S, Golpon H, Cool CD, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) expression is decreased in pulmonary hypertension and affects endothelial cell growth. Circ Res. 2003;92:1162–9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000073585.50092.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nisbet RE, Sutliff RL, Hart CM. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in pulmonary vascular disease. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2007/18797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calnek DS, Mazzella L, Roser S, Roman J, Hart CM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands increase release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:52–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000044461.01844.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polikandriotis JA, Mazzella LJ, Rupnow HL, Hart CM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands stimulate endothelial nitric oxide production through distinct peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-dependent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1810–6. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000177805.65864.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue I, Goto S, Matsunaga T, et al. The ligands/activators for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) and PPARgamma increase Cu2+,Zn2+-superoxide dismutase and decrease p22phox message expressions in primary endothelial cells. Metabolism. 2001;50:3–11. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.19415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang J, Kleinhenz DJ, Lassegue B, Griendling KK, Dikalov S, Hart CM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligands regulate endothelial membrane superoxide production. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C899–905. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00474.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iglarz M, Touyz RM, Amiri F, Lavoie MF, Diep QN, Schiffrin EL. Effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and -gamma activators on vascular remodeling in endothelin-dependent hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:45–51. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000047447.67827.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tian J, Smith A, Nechtman J, et al. Effect of PPARgamma inhibition on pulmonary endothelial cell gene expression: gene profiling in pulmonary hypertension. Physiol Genomics. 2009;40:48–60. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00094.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiseman DA, Wells SM, Hubbard M, Welker JE, Black SM. Alterations in zinc homeostasis underlie endothelial cell death induced by oxidative stress from acute exposure to hydrogen peroxide. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L165–77. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00459.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagi Z, Koller A, Kaley G. PPARgamma activation, by reducing oxidative stress, increases NO bioavailability in coronary arterioles of mice with Type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H742–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00718.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nisbet RE, Bland JM, Kleinhenz DJ, et al. Rosiglitazone attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in a mouse model. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2010;42:482–90. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0132OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong K, Xing D, Li P, et al. Hypoxia induces downregulation of PPAR-gamma in isolated pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells and in rat lung via transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L899–907. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00062.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu X, Murphy TC, Nanes MS, Hart CM. PPAR{gamma} regulates hypoxia-induced Nox4 expression in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells through NF-{kappa}B. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L559–66. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00090.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris MB, Ju H, Venema VJ, et al. Reciprocal phosphorylation and regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase in response to bradykinin stimulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16587–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Y, Baker JE, Zhang C, Tweddell JS, Su J, Pritchard KA., Jr Chronic hypoxia increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase generation of nitric oxide by increasing heat shock protein 90 association and serine phosphorylation. Circ Res. 2002;91:300–6. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000031799.12850.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–5. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ptasinska A, Wang S, Zhang J, Wesley RA, Danner RL. Nitric oxide activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma through a p38 MAPK signaling pathway. FASEB J. 2007;21:950–61. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6822com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wedgwood S, McMullan DM, Bekker JM, Fineman JR, Black SM. Role for endothelin-1-induced superoxide and peroxynitrite production in rebound pulmonary hypertension associated with inhaled nitric oxide therapy. Circ Res. 2001;89:357–64. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.094983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Black SM, Heidersbach RS, McMullan DM, Bekker JM, Johengen MJ, Fineman JR. Inhaled nitric oxide inhibits NOS activity in lambs: potential mechanism for rebound pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H1849–56. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.5.H1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMullan DM, Bekker JM, Parry AJ, et al. Alterations in endogenous nitric oxide production after cardiopulmonary bypass in lambs with normal and increased pulmonary blood flow. Circulation. 2000;102:III172–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bush PA, Gonzalez NE, Ignarro LJ. Biosynthesis of nitric oxide and citrulline from L-arginine by constitutive nitric oxide synthase present in rabbit corpus cavernosum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;186:308–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80808-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griendling KK, Minieri CA, Ollerenshaw JD, Alexander RW. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1994;74:1141–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abid MR, Spokes KC, Shih SC, Aird WC. NADPH oxidase activity selectively modulates vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35373–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma S, Kumar S, Wiseman DA, et al. Perinatal changes in superoxide generation in the ovine lung: Alterations associated with increased pulmonary blood flow. Vascul Pharmacol. 2010;53:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]