Abstract

Rationale: Pulmonary emphysema overlaps partially with spirometrically defined chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and is heritable, with moderately high familial clustering.

Objectives: To complete a genome-wide association study (GWAS) for the percentage of emphysema-like lung on computed tomography in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Lung/SNP Health Association Resource (SHARe) Study, a large, population-based cohort in the United States.

Methods: We determined percent emphysema and upper-lower lobe ratio in emphysema defined by lung regions less than −950 HU on cardiac scans. Genetic analyses were reported combined across four race/ethnic groups: non-Hispanic white (n = 2,587), African American (n = 2,510), Hispanic (n = 2,113), and Chinese (n = 704) and stratified by race and ethnicity.

Measurements and Main Results: Among 7,914 participants, we identified regions at genome-wide significance for percent emphysema in or near SNRPF (rs7957346; P = 2.2 × 10−8) and PPT2 (rs10947233; P = 3.2 × 10−8), both of which replicated in an additional 6,023 individuals of European ancestry. Both single-nucleotide polymorphisms were previously implicated as genes influencing lung function, and analyses including lung function revealed independent associations for percent emphysema. Among Hispanics, we identified a genetic locus for upper-lower lobe ratio near the α-mannosidase–related gene MAN2B1 (rs10411619; P = 1.1 × 10−9; minor allele frequency [MAF], 4.4%). Among Chinese, we identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with upper-lower lobe ratio near DHX15 (rs7698250; P = 1.8 × 10−10; MAF, 2.7%) and MGAT5B (rs7221059; P = 2.7 × 10−8; MAF, 2.6%), which acts on α-linked mannose. Among African Americans, a locus near a third α-mannosidase–related gene, MAN1C1 (rs12130495; P = 9.9 × 10−6; MAF, 13.3%) was associated with percent emphysema.

Conclusions: Our results suggest that some genes previously identified as influencing lung function are independently associated with emphysema rather than lung function, and that genes related to α-mannosidase may influence risk of emphysema.

Keywords: emphysema, computed tomography, multiethnic, cohort study, genetic association

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Emphysema assessment by computed tomography is only moderately correlated with lung function and occurs in the absence of spirometrically defined chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Percent emphysema is heritable and some studies suggest familial clustering of percent emphysema is greater than for lung function. Existing knowledge on the genetics of emphysema has been mostly limited to rare mutations causing α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We report the first genome-wide association study to probe the genetics of quantitative emphysema on computed tomography in a general population sample. We demonstrate that genetic loci previously associated with lung function in non-Hispanic whites also contribute to emphysema and that common variants in genes related to α-mannosidase, which degrades α1-antitrypsin, are associated with percent emphysema in Hispanics, African Americans, and Chinese.

Together, pulmonary emphysema and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are the third leading cause of death in the United States (1). Emphysema is defined by a permanent enlargement of air spaces with destruction of alveolar walls (2, 3), and COPD is defined by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible (4). Although often considered one disease, emphysema and COPD overlap less than previously thought. Emphysema on computed tomography (CT) is only moderately correlated with lung function, is absent in some patients with COPD, and occurs in the absence of COPD (5, 6).

Pulmonary emphysema is common in the general population, occurring in 30–50% of cigarette smokers, 8% of cigar smokers, and 3% of never-smokers at autopsy (7–9). Histologic studies subdivide emphysema into centrilobular, which is characterized by the loss of respiratory bronchioles and is predominantly observed in the upper lobes (10); panlobular, which is characterized by uniform destruction of the secondary pulmonary lobule and is diffuse or basilar; and paraseptal, which is characterized by single or multiple bullae and is peripheral (11). Autopsy studies suggest centrilobular and panlobular emphysema have a similar prevalence in the general population (12).

Smoking is the major environmental cause of COPD, yet less than one-third of heavy smokers develop COPD (13). Nonsmoking environmental influences and genetic differences contribute to the remaining variance in risk of COPD, and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified several promising genes for COPD and low lung function (14–18). Deficiency of α1-antitrypsin (A1AT) caused by mutations in SERPINA1 is the major established cause of panlobular emphysema (19–22).

Pulmonary emphysema can be assessed on CT scans as the percentage of emphysema-like lung, hereafter referred to as percent emphysema. Percent emphysema predicts symptoms, lung function decline, and mortality among patients with COPD and is associated with cardiac dysfunction in the general population (23–26). Yet smoking is only modestly correlated with percent emphysema (27) and few other environmental risk factors for percent emphysema have been described (28).

Because percent emphysema is heritable (29, 30), we performed a GWAS for percent emphysema on CT scan in a large, population-based cohort.

Methods

Study Sample

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) is a population-based longitudinal study of subclinical cardiovascular disease (31). Between 2000 and 2002, MESA recruited 6,814 men and women 45–84 years of age from six US sites that were free of clinical cardiovascular disease. The MESA Family Study recruited 1,595 African American and Hispanic family members ages 45–84 years of age specifically for genetic analysis and the MESA Air Pollution Study recruited an additional 257 participants (32). Participants who did not consent to genetic analyses or who had no usable genetic material were excluded, resulting in a combined sample of 7,914 participants comprising the MESA SNP Health Association Resource (SHARe) sample.

Percent Emphysema

Percent emphysema was assessed as previously described (33) for all participants on the lung fields of cardiac CT scans, which were acquired under a standardized protocol (34). Percent emphysema was defined as lung regions below −950 Hounsfield units (HU) and upper-lower lobe ratio in emphysema (henceforth termed “upper-lower lobe ratio”) was computed as the percent emphysema in the cranial one-eighth of the scan divided by the area in the caudal one-third of the imaged lung. The interscan intraclass correlation coefficient of percent emphysema on 100% replicate scans was 0.94. Percent emphysema measured from cardiac scans correlates with those from full-lung scans in the same MESA participants (33); the correlations of upper-lower lobe ratio in these participants was 0.78 comparing cardiac with full-lung scans on multiple-detector CT scanners and 0.68 comparing cardiac scans on electron beam tomography scanners with full-lung scans on multiple-detector CT scanners.

Genotyping

All participants were genotyped using the Affymetrix Human SNP array 6.0 (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA), with 897,981 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) passing study-specific quality control. IMPUTE v2 (35) was used to perform imputation (36) of an additional approximately 2 million SNPs in each race/ethnic group for inclusion in GWAS analyses. Additional details are provided in the online supplement.

Genetic Association Analysis in MESA Lung/SHARe

Race/ethnic-specific analyses were performed in linear regression models with adjustment for age, sex, study site, CT scanner, tube current, principal components of ancestry, height, weight, cigarettes per day (for current smokers only), pack-years, and asthma. Results were combined by fixed-effect meta-analyses across all four MESA race/ethnic groups.

We examined genomic control values of all GWAS for evidence of residual population stratification, undetected family structure, or other sources of inflation in type I error. GWAS results that attained a threshold of P = 5.0 × 10−8 were considered genome-wide significant. We further performed fine mapping using imputation to the 1,000 genomes (37) for genetic loci reported at genome-wide significance. Additional details are provided in the online supplement.

Replication Cohorts

We sought replication of significant SNPs from the combined analysis in two independent cohorts of European ancestry: the COPD Pathology: Addressing Critical gaps, Early Treatment and diagnosis and Innovative Concepts (COPACETIC)/NELSON study, a lung cancer screening study of smokers; and the Framingham Heart Study, a population-based cohort. In addition, we sought replication of these SNPs, as well as SNPs identified in race/ethnic-specific analysis of Hispanics and African Americans, among African Americans participants in the COPD Gene Study, a case–control study of COPD (see online supplement for details).

Additional Follow-up Studies

To follow-up on genetic association of the SNP MAN2B1 SNP rs10411619 in MESA Hispanics (see Results), we performed a case–control study of 17 Hispanic participants carrying the minor allele (C) at rs10411619 and 70 control subjects homozygous for the major allele matched on age, sex, and smoking; subjects found to be carriers of SERPINA1 S alleles were excluded. We further examined selected α-mannosidase gene regions (MAN1A1, MAN1A2, MAN1B1, MAN1C1, MAN2A1, MAN2A2, MAN2B1, MAN2B2, MAN2C1) in addition to the endoplasmic reticulum degradation-enhancing α-mannosidase–like proteins EDEM1, EDEM2, and EDEM3 for signals of genetic association in all race/ethnic groups from MESA, and in combined analysis across race/ethnic groups. Finally, we examined association of emphysema traits with gene expression of α-mannosidase genes demonstrating statistically significant SNP associations (MAN2B1 and MAN1C1; see Results) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from an independent sample of 101 individuals (see online supplement for details).

Results

Characteristics of the MESA Lung/SHARe Participants

The mean age of the 7,914 MESA Lung/SHARe participants was 62 years; 53.6% were female; and the race/ethnic distribution was 32.7% non-Hispanic white (henceforth termed “white”), 31.7% African American, 26.7% Hispanic, and 8.9% Chinese. The median percent emphysema ranged from 2.2% in African Americans to 3.6% in whites, and median upper-lower lobe ratio ranged from 0.68 in African Americans to 0.95 in Chinese. Percent emphysema and upper-lower lobe ratio traits were relatively distinct from one another, with correlations ranging from −19% to 10% within race/ethnic groups (see Table E1 in the online supplement).

Smoking history varied considerably across race/ethnic groups: 55.8% of whites, 52.9% of African Americans, 45.4% of Hispanics, and 25.2% of Chinese participants had ever smoked. Percent emphysema also exhibited heterogeneity across race/ethnic groups, with greater values among whites compared with other groups and greater upper-lower lobe ratio among Chinese compared with other groups. FEV1 divided by FVC was available for approximately half the cohort and was lower among whites compared with other groups (see Table E1).

GWAS of Emphysema Phenotypes across Race/Ethnic Groups

We completed GWAS analyses of percent emphysema and upper-lower lobe ratio at −950 HU, and for comparison at −910 HU. The results were largely similar, and all loci identified at genome-wide significance for −910 HU were also genome-wide significant for −950 HU. Here, we present primary results from analysis at −950 HU (Table 1), and results at −910 HU are shown in Table E2.

Table 1:

Summary of SNPs Reaching Genome-Wide Significance in the Genome-Wide Association Study of Percent Emphysema on Computed Tomography Scan

| Group | SNP ID (Chr: NCBI36.3 position) | Nearest Gene(s) | Effect/Other Allele | Effect Allele Freq.* | Trait | Beta | SE | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined analysis across race/ethnic groups | rs7957346 (12: 94,784,605) | SNRPF (downstream), CCDC38 (downstream) | C/A | 0.458/0.379/0.497/0.609 | Percent emphysema | −0.055 | 0.010 | 2.2 × 10−8 |

| rs10947233 (6: 32,232,402) | PPT2 (intron) | T/G | 0.033/0.020/0.009/0.227 | Percent emphysema | −0.150 | 0.027 | 3.2 × 10−8 | |

| Hispanic | rs10411619 (19: 12,613,425) | MAN2B1 (downstream) | T/C | 0.956 | Upper-lower lobe ratio | −0.177 | 0.029 | 1.1 × 10−9 |

| Chinese | rs7698250 (4: 24,124,729) | DHX15 (downstream) | T/C | 0.027 | Upper-lower lobe ratio | 0.463 | 0.073 | 1.8 × 10−10 |

| rs7221059 (17: 72,500,039) | MGAT5B (downstream) | C/A | 0.974 | Upper-lower lobe ratio | −0.328 | 0.059 | 2.7 × 10−8 |

Definition of abbreviation: SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Results are presented based on the basic model of genetic association, including adjustment for age, sex, study site, computed tomography scanner, principal components of ancestry, height, weight, tube current, cigarettes per day, pack-years, and asthma.

Effect allele frequencies of SNPs reported for meta-analysis are reported for white/African American/Hispanic/Chinese ethnic groups, respectively; effect allele frequencies less than 0.01 indicates data for the corresponding race/ethnic group were not included in meta-analysis.

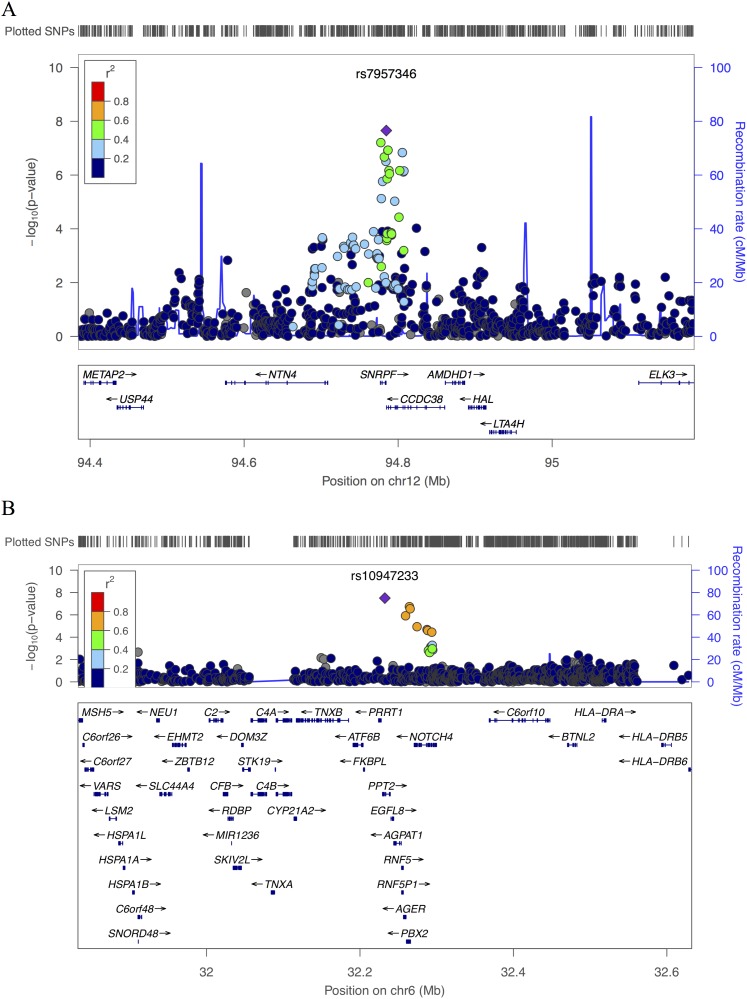

In combined analysis across race/ethnic groups, two loci reached genome-wide significance for percent emphysema (Table 1; see Table E2 and Figures E1 and E2). The top SNP for the first locus, rs7957346 (P = 2.2 × 10−8), lies between the genes SNRPF and CCDC38 (Figure 1A; see Figure E3). The associated SNP allele is common, with allele frequency ranging from 0.46 to 0.61 in the studied race/ethnic groups (Table 2). Estimated effects for rs7957346 were stronger in ever-smokers than never-smokers across race/ethnic groups (see Table E3), although this observation did not reflect a statistically significant gene-smoking interaction (P = 0.20 combined across race/ethnic groups). The second SNP, rs10947233 (P = 3.2 × 10−8), lies in an intron of the gene PPT2 (Figure 1B; see Figure E4). Allele frequencies for this SNP ranged from 0.009 to 0.227 across race/ethnic groups (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Regional association plots for statistically significant genome-wide association study regions based on meta-analysis to combine results across all Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis race/ethnic groups on (A) chromosome 12 region including SNRPF/CCDC38 for percent emphysema, and (B) chromosome 6 region including PPT2 for percent emphysema −950 HU. Both plots are generated using the LocusZoom tool with HapMap II CEU as the reference for calculating linkage disequilibrium. SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Table 2:

Detailed Race/Ethnic–Specific Results for Loci from Combined Analysis across Race/Ethnic Groups

| Trait | SNP ID (Effect/Other Allele); |

Group | N | Beta | SE | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest Gene(s) | ||||||

| Percent emphysema | rs7957346 (C/A); | White | 2,431 | −0.028 | 0.017 | 0.100 |

| SNRPF, CCDC38 | African American | 2,469 | −0.055 | 0.018 | 2.5 × 10−3 | |

| Hispanic | 2,065 | −0.085 | 0.019 | 7.1 × 10−6 | ||

| Chinese | 702 | −0.065 | 0.031 | 0.036 | ||

| Meta-analysis | −0.055 | 0.010 | 2.2 × 10−8 | |||

| Percent emphysema | rs10947233 (T/G); | White | 2,430 | −0.199 | 0.049 | 4.4 × 10−5 |

| PPT2 | African American | 2,466 | −0.148 | 0.064 | 0.020 | |

| Hispanic | — | — | — | — | ||

| Chinese | 702 | −0.120 | 0.038 | 1.5 × 10−3 | ||

| Meta-analysis | −0.150 | 0.027 | 3.2 × 10−8 |

Definition of abbreviation: SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism.

The basic model of genetic association includes adjustment for age, sex, study site, computed tomography scanner, principal components of ancestry, height, weight, tube current, cigarettes per day, pack-years, and asthma. Results for rs10947233 are not reported for Hispanics because minor allele frequency less than 0.01.

There were no genome-wide significant associations for upper-lower lobe ratio.

Replication.

Both of the identified SNPs replicated in meta-analysis across the NELSON and the Framingham Heart Study (combined n = 6,023, see Table E4; rs7957346, P = 0.016; rs10947233, P = 3.05 × 10−5; see Table E5).

Among 2,519 African Americans in the COPD Gene Study (see Table E6), rs10947233 could not be assessed because of low imputation quality and rs7957346 did not achieve nominal significance (see Table E7).

SNPs in SNRPF and PPT2, lung function, and percent emphysema.

Our top reported SNP, rs7957346, is less than 1 kb from SNP rs1036429 previously reported for pulmonary function in GWAS of approximately 90,000 individuals (38). Linkage disequilibrium with the pulmonary function SNP rs1036429 accounted for much of the observed effect of SNRPF SNP rs7957346 in whites, and to a lesser degree African Americans and Chinese, but not in Hispanics (see Table E8). The PPT2 SNP rs10947233 itself was reported in a prior GWAS for pulmonary function (39).

There was a strong independent association of both SNP rs7957346 and rs10947233 with percent emphysema after adjustment for FEV1/FVC ratio. In contrast, association of these SNPs with the FEV1/FVC ratio, which was significant in the relatively modest sample with spirometry data available, was rendered null after adjustment for percent emphysema (see Table E9). Similar analyses in the replication cohorts of whites supported the observation that percent emphysema mediates the association between these SNPs and FEV1/FVC ratio (see Table E5).

Fine mapping.

Fine mapping of the PPT2 locus identified an additional SNP rs9391855 (P = 5.6 × 10−9) (see Table E10) that showed a stronger association with percent emphysema across race/ethnic groups than the index SNP rs10947233. The most strongly associated SNP from fine mapping lies within an intron of the gene AGER at a genomic position more than 20 kb downstream of the gene PPT2. These two SNPs exhibit high linkage disequilibrium, with R2 values of 0.8, 0.83, 0.96, and 1.0, in the 1,000 Genomes AMR, EUR, ASN, and AFR reference panels, respectively.

GWAS of Emphysema Phenotypes within Race/Ethnic Groups

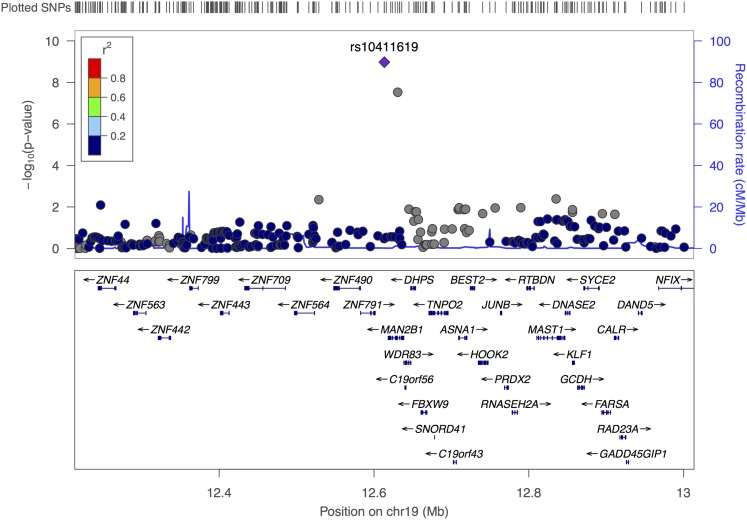

Among Hispanics, SNP rs10411619 reached genome-wide significance for association with upper-lower lobe ratio (P = 1.1 × 10−9) (Table 1). This SNP lies downstream of the α-mannosidase gene MAN2B1 (Figure 2). The MAN2B1 SNP rs10411619 minor allele (C) is somewhat common in Hispanics (minor allele frequency [MAF], 4.4%) and African Americans (MAF, 20.6%) but quite rare in the other race/ethnic groups (MAF < 1%) (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Regional association plot for statistically significant genome-wide association study region near MAN2B1 on chromosome 19, reported for analysis of upper-lower lobe ratio in emphysema in race/ethnic-specific analysis of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Hispanics. The plot is generated using HapMap II CEU as the reference panel for calculating linkage disequilibrium, using the LocusZoom tool. SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Table 3:

Detailed Race/Ethnic-Specific Results for Locus Identified Near MAN2B1 and Results for SNPs Reported as Statistically Significant in the Candidate Gene Association of Selected α-Mannosidase Genes and SERPINA1

| Trait | SNP ID (Effect/Other Allele); |

Group | Effect Allele Freq. | N | Beta | SE | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest Candidate Gene | |||||||

| Upper-lower lobe ratio in emphysema | rs10411619 (T/C); | White | 0.992 | — | — | — | — |

| MAN2B1 | African American | 0.796 | 2,440 | −0.021 | 0.013 | 0.105 | |

| (downstream) | Hispanic | 0.956 | 2,051 | −0.177 | 0.029 | 1.1 × 10−9 | |

| Chinese | 0.999 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Meta-analysis | −0.048 | 0.012 | 6.7 × 10−5 | ||||

| Percent emphysema | rs12130495 (T/G); | White | 0.083 | 2,432 | 0.010 | 0.032 | 0.753 |

| MAN1C1 | African American | 0.133 | 2,469 | −0.120 | 0.027 | 9.9 × 10−6 | |

| (intron) | Hispanic | 0.058 | 2,065 | −0.096 | 0.041 | 0.020 | |

| Chinese | 0.001 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Meta-analysis | −0.072 | 0.019 | 1.1 × 10−4 |

Definition of abbreviation: SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Results are shown for the most strongly associated SNP for each locus reaching the Bonferroni threshold for statistical significance in at least one ethnic group, under the basic model of genetic association. The number of SNPs under consideration across all candidate genes was as follows: 2,643 in whites; 2,924 in African Americans; 2,804 in Hispanics; 2,216 for Chinese; and 3,263 in meta-analysis. Results that reached the Bonferroni threshold for a particular race/ethnic group are shown in bold. SNP association results are not shown for ethnic groups with minor allele frequency less than 0.01.

Exploratory analyses stratified by principal component analysis–based clusters within the Hispanic cohort (40) indicated stronger estimated effects in the Mexican and Puerto Rican subgroups, with relatively weaker SNP effects in the Dominican/Cuban and Central/South American subgroups (see Table E11). Local ancestry analysis confirmed the SNP showed evidence of association even after adjusting for ancestry estimated from SNPs within the 4-Mb region flanking rs10411619 (see Table E12).

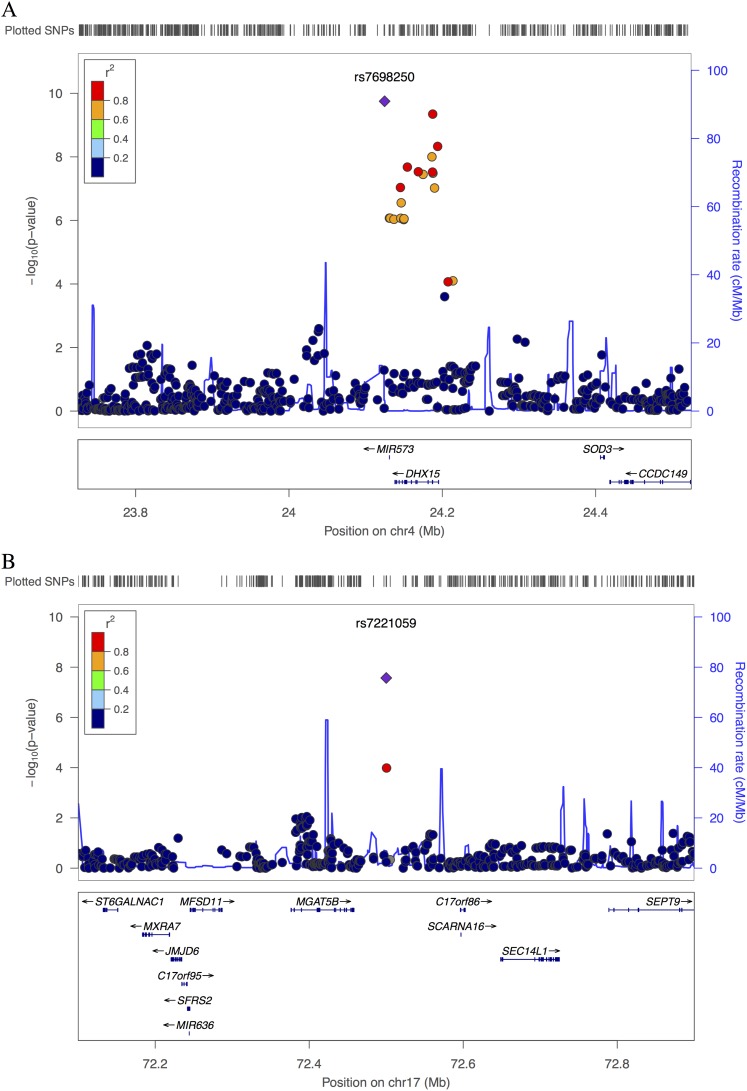

Among Chinese, we observed genome-wide significant association with upper-lower lobe ratio for two SNPs, rs7698250 (P = 1.8 × 10−10) and rs7221059 (P = 2.7 × 10−8) (Table 1). The SNP rs7698250 lies downstream of the gene DHX15 (Figure 3A) and has a higher frequency in Chinese (MAF, 2.7%) and African Americans (MAF, 4.9%) than in Hispanics (MAF, 1.2%) and whites (MAF <1%). SNP rs7221059 lies downstream of the gene MGAT5B (Figure 3B) and has a relatively lower frequency in Chinese (MAF, 2.6%) compared with whites (MAF, 19.3%), African Americans (MAF, 35.1%), and Hispanics (MAF, 26.8%). MGAT5B is a glycosyltransferase that acts on α-linked mannose of N-glycans (41), suggesting a shared pathway with MAN2B1.

Figure 3.

Regional association plot for statistically significant genome-wide association study regions identified for upper-lower lobe ratio in emphysema in race/ethnic-specific analysis of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis Chinese. The plots for the loci near (A) DHX15 and (B) MGAT5B are generated using HapMap II JPT+CHB as the reference panel for calculating linkage disequilibrium using the LocusZoom tool. SNP = single-nucleotide polymorphism.

There were no genome-wide significant associations for percent emphysema in analyses stratified by race/ethnicity.

Case–control study of plasma A1AT levels and emphysema relating to MAN2B1.

α-Mannosidase degrades mannose but also accelerates degradation of A1AT (42). Altered α-mannosidase isoenzymes have been reported in individuals carrying rare severe deficiency mutations (PiZZ) associated with A1AT deficiency (43) and mutations in an α-mannosidase–related gene have been implicated in the onset of end-stage liver disease in individuals with PiZZ (44).

Cases with MAN2B1 rs10411619 minor allele (C) had increased plasma levels of A1AT compared with control subjects (see Tables E14 and E15) (estimated effect = 15.9 mg/dl; P = 0.015). They also had lower levels of percent emphysema in the basilar lung (estimated effect = −1.1%; P = 0.022), whereas the effect on percent emphysema in the upper-lobe did not reach nominal significance (P = 0.84). None of the minor allele carriers had pulmonary emphysema on qualitative assessment by a thoracic radiologist (J.H.M.A.) masked to case status, whereas 5 (7.0%) of the 71 control subjects had observable emphysema. These results, in conjunction with the overall genetic association results for rs10411619, suggest the MAN2B1 SNP minor allele confers protection against (basilar) emphysema through increased levels of A1AT.

Candidate gene study of α-mannosidase–related genes.

MAN1C1 SNP rs12130495 was statistically significantly associated at the candidate gene level (Bonferroni threshold of 0.05/2,924 = 1.7 × 10−5) with percent emphysema in African Americans (P = 9.9 × 10−6). The associated allele was highly polymorphic in African Americans, Hispanics, and whites, but not in Chinese (Table 3). Evidence of association in African Americans was strengthened (P = 7.7 × 10−6) (see Table E12) after adjustment for local ancestry computed for the 4-Mb region flanking this SNP.

Replication.

There was a consistent direction of association between MAN2B1 SNP rs10411619 with upper-lower lobe ratio among African Americans, although it did not reach nominal statistical significance, and MAN1C1 SNP rs12130495 replicated among Hispanics (P = 0.020) (Table 3).

Among SNPs identified in Chinese, we were unable to evaluate SNP rs7698250 among other race/ethnic groups in part because of low MAF and in part because of poor imputation quality, and SNP rs7221059 did not demonstrate evidence of association (all race/ethnic–specific P values > 0.1) (see Table E13).

There was no evidence that SNPs rs10411619 and rs12130495 were associated with percent emphysema among 1,621 African Americans with COPD and control subjects or among 898 African American control subjects without COPD in the COPDGene Study (see Table E7).

Expression of MAN2B1 and MAN1C1 and Emphysema Phenotypes

MAN2B1 expression was associated with reduced upper-lower lobe ratio in a fully adjusted regression model (one-tailed nominal P = 0.047) (see Table E16), whereas MAN1C1 expression was associated with increased percent emphysema (one-tailed nominal P = 0.026). For both gene expression results, the observed direction of effect was consistent with the hypothesis that α-mannosidases degrade A1AT, yielding increased percent emphysema and increased basilar emphysema in particular.

Association of SNPs from Previous GWAS of Airflow Obstruction and Emphysema

We examined SNPs in genes previously reported to be associated with airflow obstruction, COPD (14–17), and radiologist-read emphysema (45). After multiple testing correction for examination of 11 SNPs related to COPD, we found statistically significant associations for the RARB region SNP rs1997352 with percent emphysema among whites (P = 0.001) (see Table E17); and for HHIP SNP rs13141641 with percent emphysema among whites (P = 0.0036) and in combined analysis across race/ethnic groups (P = 2.3 × 10−5).

Discussion

This GWAS of percent emphysema and upper-lower lobe ratio on CT scan identified two SNPs in or near the genes SNRPF and PPT2 that were consistent across all four racial/ethnic groups, replicated in two independent cohorts of European ancestry and were independent of quantitative measures of lung function. We further identified loci for upper-lower lobe ratio in MAN2B1, MAN1C1, and MGAT5B among Hispanics, African Americans, and Chinese, respectively, all of which relate to α-mannosidase. The minor allele at the implicated MAN2B1 SNP was associated with increases in A1AT levels and less basilar emphysema, suggesting a novel modulation of the mannosidase-A1AT pathway that may be relevant to the etiology of emphysema.

This report, which represents the largest GWAS of individuals with measures of emphysema on CT scan to date, found associations for percent emphysema among approximately 8,000 individuals in genomic regions previously implicated in large-scale GWAS meta-analysis of spirometric measures of pulmonary function in up to 90,000 individuals of European descent (38, 39). Our analyses indicate both of the SNPs we have reported here are more strongly associated with emphysema than with pulmonary function, and their association with pulmonary function is likely mediated by their association with percent emphysema. Additional fine mapping of the PPT2 region revealed a novel SNP in the AGER gene, highlighting potential ambiguity in identifying the causal gene underlying this genetic association signal. sRAGE, a protein product of AGER, was recently reported as a biomarker of emphysema in patients with COPD (45).

In the GWAS among Hispanics, we identified an SNP near the gene MAN2B1 that was statistically significantly associated with upper-lower lobe ratio. We found increased levels of A1AT among carriers of the minor allele at the MAN2B1 SNP rs10411619 in a selected group of MESA Hispanic participants. These results suggest this variant may confer additional protection of the lung against elastase in response to increased levels of A1AT. Further investigation of related candidate genes identified SNPs in MAN1C1 associated with percent emphysema among African Americans, a finding that replicated among MESA Hispanics. In an independent multiethnic cohort, the MESA COPD Study, gene expression of MAN2B1 in peripheral monocytes demonstrated statistically significant association with reduced upper-lower lobe ratio and gene expression of MAN1C1 was associated with increased percent emphysema. The identification of associations of emphysema with common variants in the α-mannosidase pathway raises the question as to whether common variants in SERPINA1 might be associated with emphysema. Our results (data not shown) indicate little to no association between known common functional variants in SERPINA1 and emphysema.

We observed consistent directions of effect for each of the statistically significant SNPs reported here in our genetic association studies, with decreased percent emphysema for SNPs associated with percent emphysema and increased upper-lower lobe ratio for SNPs associated with upper-lower lobe ratio. Thus, our study suggests a predominance of protective variants against emphysema or basilar emphysema, which may be crucial in development of therapeutics for prevention of disease. In particular, our observations suggest α-mannosidases could be an effective target for prevention and treatment of emphysema.

In addition, DHX15 is an ATP-dependent RNA helicase that plays a regulatory role in pre-mRNA splicing and has been shown to interact with RBM15 (47), a gene in the 3p21.3 genetic locus for breast and lung cancers (48, 49). We note, however, that both genetic association findings reported from race/ethnic-specific analysis of Chinese are for relatively less frequent variants with MAF in the range of 2.5–3%. Therefore, the Chinese-specific results should be interpreted with caution.

SNRPF, PPT2, and HHIP demonstrated consistent associations across race/ethnic groups, suggesting that some genes have consistent effects on the risk or severity of emphysema across all race/ethnic groups. However, MGAT5B SNP rs7221059 seen at genome-wide significance in Chinese was notably less frequent in Chinese compared with whites, African Americans, and Hispanics yet revealed no consistent associations in these other groups. Differing linkage disequilibrium and environmental factors present possible explanations for race/ethnic differences in the observed genetic associations.

Limitations of the study include a modest sample size for GWAS, particularly among Chinese; however, the present study is the largest GWAS of quantitative lung CT phenotypes to date. The MESA cardiac scans did not include the lung apices; however, we have previously validated them against full-lung scans (33), they have confirmed multiple prior hypotheses (25), they have shown prognostic significance (50), and, perhaps most importantly, they included the region of the lung most relevant to A1AT-related emphysema.

Whereas the combined analysis replicated in two independent cohorts of Europeans and the SNP in MAN1C1 replicated in MESA Hispanics, none of the SNPs identified in MESA replicated in African American smokers from the COPDGene Study. We speculate that oversampling of COPD cases, which may bias results of analysis for quantitative phenotypes, such as percent emphysema, may have contributed to the null results in the latter study. In addition, only percent emphysema was available for replication analysis in COPDGene, whereas it would have been preferable to examine upper-lower lobe ratio. Finally, we did not pursue replication of race/ethnic-specific results in cohorts of Hispanics or Chinese, because MESA is, to our knowledge, the only large-scale cohort representing these groups and having both GWAS and percent emphysema phenotypes available.

We report the first GWAS to probe the genetics of quantitative measures of emphysema using high-quality CT phenotypes in a general population sample. Our results suggest morphologic assessment of the lung on CT can build substantially on previous knowledge of the genetics of emphysema, which has been limited almost entirely to rare mutations causing A1AT deficiency. The observed findings suggest that common variants in loci previously associated with lung function among whites actually contribute to emphysema and that common variants in genes related to α-mannosidase, which degrades A1AT, may be associated with emphysema in Hispanics, African Americans, and Chinese.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Kenneth Rice at the University of Washington for valuable input that improved the manuscript. The authors thank the participants, investigators, and study staff of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, COPACETIC/NELSON, FHS, and COPDGene. A full listing of acknowledgments is provided in the online supplement.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant RC1HL100543. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and the MESA SNP Health Association Resource (SHARe) project are conducted and supported by contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95169 and RR-024156 from the NHLBI and RR024156 and ES09089. MESA Air is conducted and supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency in collaboration with MESA Air investigators, with support provided by grant RD83169701. Funding for MESA SHARe genotyping was provided by NHLBI Contract N02-HL-6-4278. MESA Family is conducted and supported in collaboration with MESA investigators; support is provided by grants and contracts R01HL071051, R01HL071205, R01HL071250, R01HL071251, R01HL071252, R01HL071258, R01HL071259, M01-RR00425, UL1RR033176, and UL1TR000124. The MESA Lung and MESA COPD Studies are funded by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL077612 and R01HL093081. The COPACETIC study was funded by the FP7 grant from European Union, Grant Agreement No. 201379. The Framingham Heart Study was supported by the NHLBI Framingham Heart Study (contract number N01-HC-25195) and its contract with Affymetrix, Inc., for genotyping services (contract number N02-HL-6-4278). The COPDGene study was supported by NHLBI R01 HL084323, P01 HL083069, P01 HL105339, and R01 HL089856 (E.K.S.); K08 HL097029 and R01 HL113264 (M.H.C.), and R01 HL089897 (J.D.C.). The COPDGene study (NCT00608764) is also supported by the COPD Foundation through contributions made to an Industry Advisory Board comprised of AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Pfizer, Siemens, and Sunovion.

Author Contributions: Study design: G.R.W., C.W., P.Z., D.S.P., J.D.C., T.H.B., J.E.H., E.K.S., J.D., G.T.O., H.M.B., S.S.R., and R.G.B. Phenotype data acquisition and quality control: A.M., J.S., W.G., M.H.C., E.A.H., H.B., M.B., J.H.M.A., G.R.W., J.J.C., J.D.K., T.P., C.A.P., C.W., H.J.M.G., F.N.R., M.L.B., R.P., B.M.S., L.J.R., K.D.H.S., J.D.C., T.H.B., J.E.H., E.K.S., J.D., G.T.O., H.M.B., and R.G.B. Genotype data acquisition and quality control: A.M., J.S., W.G., M.H.C., T.H.B., E.K.S., J.D., G.T.O., H.M.B., and S.S.R. Data analysis: A.M., J.S., W.G., M.H.C., T.P., C.A.P., D.R., T.H.B., J.E.H., E.K.S., J.D., S.S.R., and R.G.B. Critical revision of manuscript: all authors.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1061OC on January 2, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Liu X.Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults aged 18 and over in the United States, 1998–2009 NCHS Data Brief 2011(63)1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The definition of emphysema. Report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Division of Lung Diseases workshop. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:182–185. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Ma P, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS GOLD Scientific Committee. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and World Health Organization Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): executive summary. Respir Care. 2001;46:798–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vestbo J, Hogg JC. Convergence of the epidemiology and pathology of COPD. Thorax. 2006;61:86–88. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.046227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gietema HA, Zanen P, Schilham A, van Ginneken B, van Klaveren RJ, Prokop M, Lammers JW. Distribution of emphysema in heavy smokers: impact on pulmonary function. Respir Med. 2010;104:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agusti A, Calverley PM, Celli B, Coxson HO, Edwards LD, Lomas DA, MacNee W, Miller BE, Rennard S, Silverman EK, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) investigators. Characterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir Res. 2010;11:122. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leopold JG, Gough J. The centrilobular form of hypertrophic emphysema and its relation to chronic bronchitis. Thorax. 1957;12:219–235. doi: 10.1136/thx.12.3.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thurlbeck WM. A clinico-pathological study of emphysema in an American hospital. Thorax. 1963;18:59–67. doi: 10.1136/thx.18.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auerbach O, Hammond EC, Garfinkel L, Benante C. Relation of smoking and age to emphysema. Whole-lung section study. N Engl J Med. 1972;286:853–857. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197204202861601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kemp SV, Polkey MI, Shah PL. The epidemiology, etiology, clinical features, and natural history of emphysema. Thorac Surg Clin. 2009;19:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litmanovich D, Boiselle PM, Bankier AA. CT of pulmonary emphysema: current status, challenges, and future directions. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:537–551. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson AE, Jr, Hernandez JA, Eckert P, Foraker AG. Emphysema in lung macrosections correlated with smoking habits. Science. 1964;144:1025–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.144.3621.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snider GL. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: risk factors, pathophysiology and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Med. 1989;40:411–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.40.020189.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilk JB, Shrine NR, Loehr LR, Zhao JH, Manichaikul A, Lopez LM, Smith AV, Heckbert SR, Smolonska J, Tang W, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify CHRNA5/3 and HTR4 in the development of airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:622–632. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0366OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pillai SG, Ge D, Zhu G, Kong X, Shianna KV, Need AC, Feng S, Hersh CP, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, et al. ICGN Investigators. A genome-wide association study in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): identification of two major susceptibility loci. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho MH, Boutaoui N, Klanderman BJ, Sylvia JS, Ziniti JP, Hersh CP, DeMeo DL, Hunninghake GM, Litonjua AA, Sparrow D, et al. Variants in FAM13A are associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:200–202. doi: 10.1038/ng.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho MH, Castaldi PJ, Wan ES, Siedlinski M, Hersh CP, Demeo DL, Himes BE, Sylvia JS, Klanderman BJ, Ziniti JP, et al. ICGN Investigators; ECLIPSE Investigators; COPDGene Investigators. A genome-wide association study of COPD identifies a susceptibility locus on chromosome 19q13. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:947–957. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, Cohn M, Langerman F, Moran S, Tarragona N, Moukhachen H, Venugopal R, Hasimja D, Kao E, et al. The COPD genetic association compendium: a comprehensive online database of COPD genetic associations. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:526–534. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Needham M, Stockley RA. Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. 3: Clinical manifestations and natural history. Thorax. 2004;59:441–445. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.006510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turino GM, Seniorrm, Garg BD, Keller S, Levi MM, Mandl I. Serum elastase inhibitor deficiency and alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency in patients with obstructive emphysema. Science. 1969;165:709–711. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3894.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laurell CB, Eriksson S. The electrophoretic alpha 1-globulin pattern of serum in alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1963;15:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eriksson S. Pulmonary emphysema and alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Acta Med Scand. 1964;175:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1964.tb00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vestbo J, Edwards LD, Scanlon PD, Yates JC, Agusti A, Bakke P, Calverley PM, Celli B, Coxson HO, Crim C, et al. ECLIPSE Investigators. Changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 second over time in COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1184–1192. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haruna A, Muro S, Nakano Y, Ohara T, Hoshino Y, Ogawa E, Hirai T, Niimi A, Nishimura K, Chin K, et al. CT scan findings of emphysema predict mortality in COPD. Chest. 2010;138:635–640. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barr RG, Bluemke DA, Ahmed FS, Carr JJ, Enright PL, Hoffman EA, Jiang R, Kawut SM, Kronmal RA, Lima JA, et al. Percent emphysema, airflow obstruction, and impaired left ventricular filling. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:217–227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grydeland TB, Dirksen A, Coxson HO, Eagan TM, Thorsen E, Pillai SG, Sharma S, Eide GE, Gulsvik A, Bakke PS. Quantitative computed tomography measures of emphysema and airway wall thickness are related to respiratory symptoms. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:353–359. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200907-1008OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grydeland TB, Dirksen A, Coxson HO, Pillai SG, Sharma S, Eide GE, Gulsvik A, Bakke PS. Quantitative computed tomography: emphysema and airway wall thickness by sex, age and smoking. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:858–865. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00167908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lovasi GS, Diez Roux AV, Hoffman EA, Kawut SM, Jacobs DR, Jr, Barr RG. Association of environmental tobacco smoke exposure in childhood with early emphysema in adulthood among nonsmokers: the MESA-lung study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:54–62. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou JJ, Cho MH, Castaldi PJ, Hersh CP, Silverman EK, Laird NM. Heritability of COPD and related phenotypes in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:941–947. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0263OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel BD, Coxson HO, Pillai SG, Agustí AG, Calverley PM, Donner CF, Make BJ, Müller NL, Rennard SI, Vestbo J, et al. International COPD Genetics Network. Airway wall thickening and emphysema show independent familial aggregation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:500–505. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-059OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR, Jr, Kronmal R, Liu K, et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaufman JD, Adar SD, Allen RW, Barr RG, Budoff MJ, Burke GL, Casillas AM, Cohen MA, Curl CL, Daviglus ML, et al. Prospective study of particulate air pollution exposures, subclinical atherosclerosis, and clinical cardiovascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and Air Pollution (MESA Air) Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:825–837. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffman EA, Jiang R, Baumhauer H, Brooks MA, Carr JJ, Detrano R, Reinhardt J, Rodriguez J, Stukovsky K, Wong ND, et al. Reproducibility and validity of lung density measures from cardiac CT scans: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) lung study. Acad Radiol. 2009;16:689–699. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, McNitt-Gray M, Arad Y, Jacobs DR, Jr, Sidney S, Bild DE, Williams OD, Detrano RC. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: standardized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology. 2005;234:35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet 209. 5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howie B, Marchini J, Stephens M. Genotype imputation with thousands of genomes. G3 (Bethesda) 2011;1:457–470. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soler Artigas M, Loth DW, Wain LV, Gharib SA, Obeidat M, Tang W, Zhai G, Zhao JH, Smith AV, Huffman JE, et al. Genome-wide association and large-scale follow up identifies 16 new loci influencing lung function. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1082–1090. doi: 10.1038/ng.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hancock DB, Eijgelsheim M, Wilk JB, Gharib SA, Loehr LR, Marciante KD, Franceschini N, van Durme YM, Chen TH, Barr RG, et al. Meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies identify multiple loci associated with pulmonary function. Nat Genet. 2010;42:45–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manichaikul A, Palmas W, Rodriguez CJ, Peralta CA, Divers J, Guo X, Chen WM, Wong Q, Williams K, Kerr KF, et al. Population structure of Hispanics in the United States: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaneko M, Alvarez-Manilla G, Kamar M, Lee I, Lee JK, Troupe K, Zhang WJ, Osawa M, Pierce M. A novel beta(1,6)-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V (GnT-VB)(1) FEBS Lett. 2003;554:515–519. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hosokawa N, Wada I, Hasegawa K, Yorihuzi T, Tremblay LO, Herscovics A, Nagata K. A novel ER alpha-mannosidase-like protein accelerates ER-associated degradation. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:415–422. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson DB, Diven WF, Glew RH. Altered alpha-mannosidase isoenzymes in the liver in hepatic cirrhosis. Enzyme. 1982;27:99–107. doi: 10.1159/000459032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan S, Huang L, McPherson J, Muzny D, Rouhani F, Brantly M, Gibbs R, Sifers RN. Single nucleotide polymorphism-mediated translational suppression of endoplasmic reticulum mannosidase I modifies the onset of end-stage liver disease in alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. Hepatology. 2009;50:275–281. doi: 10.1002/hep.22974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kong X, Cho MH, Anderson W, Coxson HO, Muller N, Washko G, Hoffman EA, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, Lomas DA, et al. ECLIPSE Study NETT Investigators. Genome-wide association study identifies BICD1 as a susceptibility gene for emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:43–49. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0541OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng DT, Kim DK, Cockayne DA, Belousov A, Bitter H, Cho MH, Duvoix A, Edwards LD, Lomas DA, Miller BE, et al. TESRA and ECLIPSE Investigators. Systemic soluble receptor for advanced glycation endproducts is a biomarker of emphysema and associated with AGER genetic variants in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:948–957. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0247OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niu Z, Jin W, Zhang L, Li X. Tumor suppressor RBM5 directly interacts with the DExD/H-box protein DHX15 and stimulates its helicase activity. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:977–983. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sundaresan V, Chung G, Heppell-Parton A, Xiong J, Grundy C, Roberts I, James L, Cahn A, Bench A, Douglas J, et al. Homozygous deletions at 3p12 in breast and lung cancer. Oncogene. 1998;17:1723–1729. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senchenko VN, Liu J, Loginov W, Bazov I, Angeloni D, Seryogin Y, Ermilova V, Kazubskaya T, Garkavtseva R, Zabarovska VI, et al. Discovery of frequent homozygous deletions in chromosome 3p21.3 LUCA and AP20 regions in renal, lung and breast carcinomas. Oncogene. 2004;23:5719–5728. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oelsner EC, Hoffman EA, Folsom AR, Carr JJ, Enright P, Kawut SM, Kronmal R, Lederer DJ, Lima JA, Lovasi GS, et al. Percent emphysema is associated with all-cause mortality in a general population sample: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) lung study [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A3643. [Google Scholar]