After decades of focused interest on the pulmonary vascular component of pulmonary hypertension (PH), there is a growing recognition of the importance of addressing the mechanisms of the failing right ventricle (RV) in the disease (1). This awareness has occurred as several of the therapies developed to treat the pulmonary vascular component of PH, although they improve quality of life and prolong survival, do not lead to resolution of the underlying vascular lesions (2); moreover, it has been suspected that some therapies, particularly prostanoids, may promote RV function, rather than inhibit or regress pulmonary vascular disease.

Largely following the concepts applied to explain left heart failure, pathogenic hypotheses to explain RV failure in PH focus on a growing number of potential mechanisms, largely derived from animal studies. These include (1) rarefaction of intramyocardial capillaries leading to a decrease in myocyte oxygen supply (3); (2) oxidative stress (4); (3) metabolic impairment of the RV with a shift toward glycolysis, possibly related to hypoperfusion and activation of hypoxia signaling (5); and (4) mitochondrial energetic failure (6). The investigations of Hemnes and collaborators (pp. 325–334) reported in this issue of the Journal provide a new angle in PH-related RV failure, as they point toward abnormalities of fat metabolism in the RV myocyte in the setting of mutations of bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2) (7).

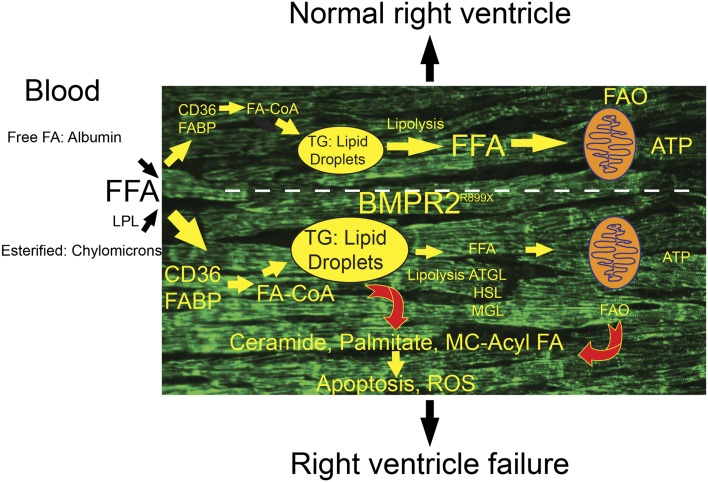

Building on the clinical evidence that patients with hereditary pulmonary arterial hypertension (HPAH) have a more severe clinical presentation, the authors analyzed transgenic mice that express a conditional BMPR2 mutant that abrogates BMP signaling in a dominant-negative fashion, as well as human RV samples from patients with HPAH. They propose that dysfunctional BMPR2 signaling in RV myocytes leads to increased triglyceride deposits, increased ceramide levels, and potential fat toxicity (Figure 1). The failing RV would therefore undergo an injury process similar to that seen with the liver and left ventricle (LV) in obese patients or those with metabolic syndrome (8).

Figure 1.

Fatty acid (FA) uptake and intracellular fate in normal or failing right ventricle (RV), particularly in the setting of global overexpression of bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2) R899X mutation. In normal RV, CD36- and fatty acid–binding protein (FABP)-mediated uptake of free fatty acids (FFA) originating from circulating lipoprotein pools (via lipoprotein lipase hydrolysis [LPL]) or bound with albumin is matched with fatty acid oxidation (FAO). This leads to small levels of triglyceride (TG) accumulation in lipid droplets. In the setting of BMPR2 R899X mutation, lipid droplets accumulate, potentially driven by enhanced FFA uptake, decreased TG hydrolysis (mediated by adipocyte TG lipase [ATGL], hormone-sensitive lipase [HLP], and monoglyceride lipase [MGL]), and/or decreased FAO. Myocyte accumulation of TG engenders production of lipotoxic intermediates, including palmitate, medium-chain fatty acids, and ceramide. Mitochondria dysfunction may also contribute to increased lipotoxicity (based on Reference 8). CoA = coenzyme A; MC = medium size chain; ROS = reactive oxygen species.

The mouse model used in this study has a mutation in the cytoplasmic tail, originally found in patients with HPAH, that results in premature truncation of the BMPR2 protein (9). BMPR2 receives signals from the BMP class of extracellular proteins and results in activation of multiple signaling pathways intracellularly, including phosphorylation of Smads 1, 5, and 8, Rack 1, p38 and p42/44 MAP kinases, and c-Src. While preserving Smad1/5/8 signaling, the R899X mutation increases p38 and p42/44 phosphorylation (10). Prior transgenic mouse studies with an inducible smooth muscle cell–specific driver (Sm22) of the BMPR2R899X demonstrated the development of PH with a phenotype that included elevated right ventricular systolic pressure, muscularized pulmonary arteries, and pulmonary vascular dropout by angiography (10).

The present study demonstrated that mice with global expression of mutant BMPR2 (via a Rosa26 promoter)—but not with smooth muscle–specific overexpression—develop a dysfunctional RV phenotype. BMPR2 is known to be critical in cardiogenesis; knockdown results in embryonic lethality via abnormal homeobox expression and heart formation (11), particularly involving positioning of the outflow tracts, remodeling of the arterioventricular cushion, and development of the valve leaflets (12). One mechanism that may be involved in the dysfunctional RV phenotype is exacerbated TGF-β signaling resulting from decreased BMPR2 signaling (13), which in combination could trigger maladaptive myocardial fibrosis. An elevation in serum TGF-β1 is associated with the subsequent development of left-sided heart failure in older adults (14), and a murine model of myocardial infarction demonstrates increased TGF-β signal after injury (15). Although these processes may have relevance to the RV dysfunction seen in HPAH, the data of Hemnes and colleagues indicate a potential role for fat-induced cardiotoxicity and altered cellular metabolism for the BMPR2 mutation–dependent RV dysfunction (7).

Cardiomyocytes have a unique dependence on aerobic metabolism—rich in mitochondria, unable to store glycogen, and highly preferential toward fatty acid oxidation as a source of fuel, they rely heavily on delivery of free fatty acids (FFA) bound to albumin as well as fatty acids released from triacylglycerol contained within very low–density lipoproteins or chylomicrons by lipoprotein lipase (16). The heart transitions from a glycolytic metabolism to energetically favorable fatty acid oxidation after birth; the reverse occurs during aging (8, 17). Cardiac myocytes uptake fatty acids by passive diffusion and active transport via fatty acid translocase/CD36 and fatty acid transporter proteins (8). Additionally, the myocardium contains labile stores of triacylglycerol, which serve as an endogenous source of FFA after lipolysis by adipose triacylglycerol lipase. Ultimately, FFA undergo conversion to long-chain acyl coenzyme A (CoA) esters by fatty acyl CoA synthetase and then conversion to long-chain acylcarnitine by carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 allowing for shuttling into the mitochondria and subsequent fatty acid β-oxidation (18) (Figure 1). Fatty acid oxidation produces more ATP per mole than glucose, at the expense of an approximately 35% higher oxygen consumption (17).

The fate of fatty acids in the heart muscle involves catabolism directed toward energetics rather than primarily storing fatty acids in lipid droplets (as present in adipocytes). The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are major transcriptional regulators of fatty acid oxidation, and both pharmacologic activation and targeted overexpression of this system has been demonstrated to lead to cardiac lipid accumulation with cardiomyopathy and liver steatosis, resembling alterations seen metabolic syndrome and obesity (19). Further, disruption of this flux of FFA to β-oxidation (such as targeted overexpression of fatty acid transporter proteins [20] or deficiency of carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 [21]) has been demonstrated to result in cardiomyopathies. The conversion of long-chain acyl CoAs to complex intermediates such as palmitic acid (which serves as precursor for downstream signaling lipids ceramide and diacylglycerol) has been implicated in the damaging effects of lipotoxicity (22). In metabolic syndrome, accumulation of intracellular lipids can increase the signaling molecular ceramide, which induces apoptosis via a Bax-dependent mechanism. Moreover, palmitate can cause increased oxidative stress and thus mediate lipotoxicity (23). Hemnes and colleagues showed that the RV ceramide may be higher in the BMPR2 mutant hearts and thus mediate cardiotoxicity (7). More in-depth investigation of the role of ceramide in the RV dysfunction would require a combination of pharmacological and genetic interventions to block ceramide synthetic pathways (24). In addition, increases in diacylglycerol can up-regulate protein kinase C, leading to inhibition of the insulin signaling pathway and eventual apoptosis (25). Finally, accumulation of triacylglycerols can cause mitochondrial dysfunction as shown in animal models of obesity, attributed to reduction in respiratory complexes key to oxidative phosphorylation (22).

An alternative mechanism of potential RV dysfunction in the setting of increased lipid deposition may also explain the findings of Hemnes and colleagues (7). There is a reciprocal regulation of glucose versus lipid oxidative substrates, also known as the Randle cycle (26, 27). If the failing RV harboring the BMPR2 R899X mutation has increased glucose uptake, funneling increased pyruvate into the mitochondria, the ensuing generation of increased levels of citrate would lead to heightened fatty acid synthesis via activation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, with lipid droplet accumulation.

It is apparent that the heart failure seen in mice with the BMPR2 R899X mutation is restricted to the RV, with sparing of the LV, despite a predicted global heart expression of the mutated receptor. The exclusive RV phenotype indicates that its dysfunction requires an elevation of pulmonary artery pressures or afterload to trigger the maladaptive processes outlined above. Whether a similar RV dysfunction can be triggered by induction of LV strain and the response to exercise (which causes “beneficial” remodeling) will be informative regarding the mechanisms underlying RV failure in the setting of mutations of BMPR2.

Although the mechanisms of RV dysfunction in PH remain to be clarified, the findings of Hemnes and colleagues suggest interventional experiments that may have therapeutic potential (7). Their data with metformin suggest that the activation of AMP kinase may promote fatty acid oxidation, leading to decreased fatty acid accumulation and improved contractility in BMPR2 R899X mutant RV. This approach is conceptually in line with potential interventions to decrease fatty acid uptake by blocking CD36 or fatty acid–binding protein in lipotoxic heart diseases (8). Other possibilities include diets containing medium-chain fatty acids or activation of lipolysis with hormone-sensitive lipase. However, AMP kinase is also an inhibitor of mechanistic target of rapamycin, which could attenuate hypertrophic myocyte responses and lipid accumulation.

The close interplay between glycolysis, glucose oxidation, and fat oxidation raises interesting considerations in regards to proposed interventions to the PH part of the equation. There are compelling data showing that PH consists of a state of increased glycolysis, despite the presence of oxygen (also known as the Warburg effect). Pharmacological approaches that increase glucose oxidation (and decrease glycolysis) hold promise as potential therapies for PAH: this includes activating pyruvate dehydrogenase with dichloroacetate or pharmacologically blocking fatty acid oxidation (27). Both interventions could potentially lead to increased fatty acid accumulation in the RV with potential detrimental effects, particularly in patients with familial disease via mutant BMPR2. On the other hand, those hearts harboring wild-type BMPR2 may turn to glycolysis, like that seen for the hypertensive pulmonary circulation, and potentially could benefit from activation of glucose oxidation (5).

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Cardiovascular Medical and Research Educational Fund (R.M.T.); and NIH grant K08HL105536, the Gilead Research Scholars Program in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, and American Thoracic Society Foundation/Pulmonary Hypertension Association grants (B.B.G.).

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Voelkel NF, Quaife RA, Leinwand LA, Barst RJ, McGoon MD, Meldrum DR, Dupuis J, Long CS, Rubin LJ, Smart FW, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group on Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Right Heart Failure. Right ventricular function and failure: report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on cellular and molecular mechanisms of right heart failure. Circulation. 2006;114:1883–1891. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stacher E, Graham BB, Hunt JM, Gandjeva A, Groshong SD, McLaughlin VV, Jessup M, Grizzle WE, Aldred MA, Cool CD, et al. Modern age pathology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:261–272. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0164OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogaard HJ, Natarajan R, Mizuno S, Abbate A, Chang PJ, Chau VQ, Hoke NN, Kraskauskas D, Kasper M, Salloum FN, et al. Adrenergic receptor blockade reverses right heart remodeling and dysfunction in pulmonary hypertensive rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:652–660. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0335OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahmud M, Champion HC. Right ventricular failure complicating heart failure: pathophysiology, significance, and management strategies. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2007;9:200–208. doi: 10.1007/BF02938351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piao L, Marsboom G, Archer SL. Mitochondrial metabolic adaptation in right ventricular hypertrophy and failure. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:1011–1020. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0679-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez-Arroyo J, Mizuno S, Szczepanek K, Van Tassell B, Natarajan R, dos Remedios CG, Drake JI, Farkas L, Kraskauskas D, Wijesinghe DS, et al. Metabolic gene remodeling and mitochondrial dysfunction in failing right ventricular hypertrophy secondary to pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:136–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.966127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hemnes AR, Brittain EL, Trammell AW, Fessel JP, Austin ED, Penner N, Maynard KB, Gleaves L, Talati M, Absi T, et al. Evidence for right ventricular lipotoxicity in heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:325–334. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1086OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg IJ, Trent CM, Schulze PC. Lipid metabolism and toxicity in the heart. Cell Metab. 2012;15:805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane KB, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Thomson JR, Phillips JA, III, Loyd JE, Nichols WC, Trembath RC International PPH Consortium. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-beta receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2000;26:81–84. doi: 10.1038/79226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West J, Harral J, Lane K, Deng Y, Ickes B, Crona D, Albu S, Stewart D, Fagan K. Mice expressing BMPR2R899X transgene in smooth muscle develop pulmonary vascular lesions. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L744–L755. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90255.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Y, Katsev S, Cai C, Evans S. BMP signaling is required for heart formation in vertebrates. Dev Biol. 2000;224:226–237. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beppu H, Malhotra R, Beppu Y, Lepore JJ, Parmacek MS, Bloch KD. BMP type II receptor regulates positioning of outflow tract and remodeling of atrioventricular cushion during cardiogenesis. Dev Biol. 2009;331:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrell NW, Yang X, Upton PD, Jourdan KB, Morgan N, Sheares KK, Trembath RC. Altered growth responses of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from patients with primary pulmonary hypertension to transforming growth factor-beta(1) and bone morphogenetic proteins. Circulation. 2001;104:790–795. doi: 10.1161/hc3201.094152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glazer NL, Macy EM, Lumley T, Smith NL, Reiner AP, Psaty BM, King GL, Tracy RP, Siscovick DS. Transforming growth factor beta-1 and incidence of heart failure in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Cytokine. 2012;60:341–345. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zakharova L, Nural-Guvener H, Nimlos J, Popovic S, Gaballa MA. Chronic heart failure is associated with transforming growth factor beta-dependent yield and functional decline in atrial explant-derived c-Kit+ cells. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000317. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Vusse GJ, van Bilsen M, Glatz JF. Cardiac fatty acid uptake and transport in health and disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:279–293. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuder RM, Davis LA, Graham BB. Targeting energetic metabolism: a new frontier in the pathogenesis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:260–266. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1536PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster DW. The role of the carnitine system in human metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1033:1–16. doi: 10.1196/annals.1320.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finck BN, Lehman JJ, Leone TC, Welch MJ, Bennett MJ, Kovacs A, Han X, Gross RW, Kozak R, Lopaschuk GD, et al. The cardiac phenotype induced by PPARalpha overexpression mimics that caused by diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:121–130. doi: 10.1172/JCI14080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiu HC, Kovacs A, Blanton RM, Han X, Courtois M, Weinheimer CJ, Yamada KA, Brunet S, Xu H, Nerbonne JM, et al. Transgenic expression of fatty acid transport protein 1 in the heart causes lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2005;96:225–233. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000154079.20681.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanley CA. New genetic defects in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and carnitine deficiency. Adv Pediatr. 1987;34:59–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abel ED, Litwin SE, Sweeney G. Cardiac remodeling in obesity. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:389–419. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Listenberger LL, Schaffer JE. Mechanisms of lipoapoptosis: implications for human heart disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(02)00152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrache I, Natarajan V, Zhen L, Medler TR, Richter AT, Cho C, Hubbard WC, Berdyshev EV, Tuder RM. Ceramide upregulation causes pulmonary cell apoptosis and emphysema-like disease in mice. Nat Med. 2005;11:491–498. doi: 10.1038/nm1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drosatos K, Schulze PC. Cardiac lipotoxicity: molecular pathways and therapeutic implications. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2013;10:109–121. doi: 10.1007/s11897-013-0133-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Randle PJ. Regulatory interactions between lipids and carbohydrates: the glucose fatty acid cycle after 35 years. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1998;14:263–283. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0895(199812)14:4<263::aid-dmr233>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sutendra G, Bonnet S, Rochefort G, Haromy A, Folmes KD, Lopaschuk GD, Dyck JR, Michelakis ED. Fatty acid oxidation and malonyl-CoA decarboxylase in the vascular remodeling of pulmonary hypertension. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:44ra58. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]