Abstract

Alternating-current (AC) electrokinetics involve the movement and behaviors of particles or cells. Many applications, including dielectrophoretic manipulations, are dependent upon charge interactions between the cell or particle and the surrounding medium. Medium concentrations are traditionally treated as spatially uniform in both theoretical models and experiments. Human red blood cells (RBCs) are observed to crenate, or shrink due to changing osmotic pressure, over 10 min experiments in non-uniform AC electric fields. Cell crenation magnitude is examined as functions of frequency from 250 kHz to 1 MHz and potential from 10 Vpp to 17.5 Vpp over a 100 μm perpendicular electrode gap. Experimental results show higher peak to peak potential and lower frequency lead to greater cell volume crenation up to a maximum volume loss of 20%. A series of experiments are conducted to elucidate the physical mechanisms behind the red blood cell crenation. Non-uniform and uniform electrode systems as well as high and low ion concentration experiments are compared and illustrate that AC electroporation, system temperature, rapid temperature changes, medium pH, electrode reactions, and convection do not account for the crenation behaviors observed. AC electroosmotic was found to be negligible at these conditions and AC electrothermal fluid flows were found to reduce RBC crenation behaviors. These cell deformations were attributed to medium hypertonicity induced by ion concentration gradients in the spatially nonuniform AC electric fields.

INTRODUCTION

Microdevices, also called lab-on-a-chip (LOC) and micro-Total Analysis System (μTAS), have shown great potential in quantitative chemical analysis such as single cell impedance measurements,1 cell/particle concentration,2, 3 separation,4, 5 manipulation6, 7, 8 in addition to other mechanical, biological or medical diagnostic applications. Advantages are small volume samples, short analysis time, and high efficiency.6 Disadvantages are reproducibility between cell populations, device reliability exceeding macro-scale analytical techniques, and the bulkiness of chip support systems. This work has implications in the reproducibility and reliability area.

Prior work has investigated electrolytic manipulation including electrophoresis, electroosmosis, electrothermal, and dielectrophoresis of red blood cells in direct-current (DC)9 and alternating-current (AC)7, 8 devices. Cell crenation was observed during long-term dielectrophoresis (DEP) pearl chain formation and transition (over 60 s) at length scales above 10 μm.7 Thus, this work systematically explores the physical mechanisms inducing the previously observed, but not quantified cell crenation.

Without electric fields present, cell deformation can occur due to abnormal cell physiology or chemical abnormalities,10 medium ionic strength,11 mechanical forces,12 medium pH,13 absolute temperature value,14 and rapid temperature changes.15 For healthy red blood cells, medium ionic strength, or tonicity is the most prevalent cause for cell crenation. Osmotic pressure is the osmolyte balance between medium solution and the interior of cells. Cell semipermeable membranes have ion and water channels such that water and ion content are in quasi-steady state between intra and extracellular regions. As a result, cells will absorb water to swell/hemolysis (e.g., ghosting), stay normal/healthy, or lose water to dehydrate/shrink (e.g., crenate) at medium ion concentrations that are lower than, equal to, or higher than intracellular ion concentration, respectively. In the presence of electric fields, cell electroporation and electrofusion have been observed.16

In our system, experiments demonstrate cell crenation in non-uniform AC fields with a physiological ionic buffer. Carefully constructed control experiments elucidate that pH, temperature, rapid temperature change, and electroporation are not responsible for cell deformation in our system. Physiologically relevant conductivities (1000 μS/cm) and frequencies greater than 250 kHz are utilized to avoid AC electroosmosis (ACEO). AC electrothermal (ACET) flows are quantified and do not explain the observed phenomenon. Results support that cell crenation occurs because of an osmotic imbalance generated by the formation of ion concentration gradients likely induced by an ion flux described by the following form of the Nernst-Planck equation:

| (1) |

where, for species i, is total ion flux, is charge valence, is ion mobility, is ion concentration, φ is electric potential, is diffusivity, v is convective flux velocity, and is reaction rate. The physical reasons for a bulk ion concentration gradient formation is discussed with respect to electric migration (first term), countered by diffusion (second term), fluidic flow (third term), and Faradaic currents (fourth term).

Red blood cell (RBC) crenation, which is observed at longer length and time scales, is introduced in Sec. 3B. In Sec. 3C, experiments are discussed that examine potential and peak-to-peak dependency of the RBC crenation. Optically observed 2D cell area changes are quantified to track cell deformation. In Sec. 3D, control experiments are discussed that examine cell healthiness, electroporation, electric field induced flows, DEP forces, temperature, and medium pH. We conclude that the observed cell crenation is due to an osmotic pressure change induced by an ion concentration increase in the bulk fluid at longer time scales. These experimental results challenge the assumption that fluid within nonuniform AC microfluidic systems has constant uniform ion concentrations at distances larger than the double-layer thickness. Further implications of these observed results are that induced ion propagation can influence local electrical conductivity, conductivity, density, and other fluid properties thus inducing unexpected fluid behaviors and cell/particle responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Device fabrication

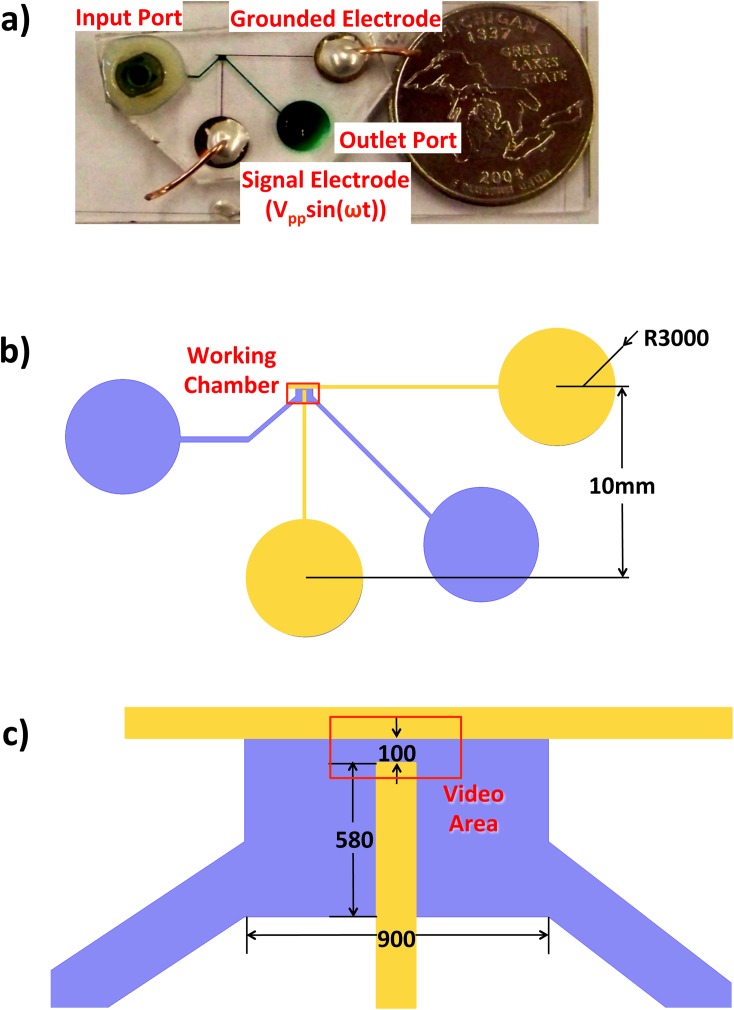

Microdevices were custom fabricated with a 100 μm gap between perpendicular Ti/Au electrodes and overlaid by a 900 μm × 800 μm and 70 μm high Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) fluidic chamber.7 Standard soft photolithography fabrication procedures (EVG 620 Mask Aligner) were followed8 for both (a) Ti/Au electrodeposition (Perkin-Elmer 2400 sputter tool) to a depth of 200 nm and (b) fluidic layer relief masters. Figure 1 shows (a) a photo of the entire device, (b) a cartooned view of the device layout with electrodes in yellow and fluidic chambers and channels in blue, and (c) magnified view of the experimental test chamber with the microscope viewing area outlined in red.

Figure 1.

Microfluidic device configuration with a PDMS fluidic layer bonded on a microfabricated Ti-Au electrode glass slide. (a) Photo of device with fluid channels filled with green dye. (b) Device design with Ti-Au electrodes shown in yellow and fluidic channels and chamber shown in blue. The red box outlines the working chamber. (c) Magnified view of working chamber with dimension in micrometers. The red box is the observation area recorded with a 63× video microscope.

Materials

Human blood samples from volunteer donors were obtained by certified phlebotomists. Whole blood was stored at 4 °C within 10 min after donation. Experiments were completed within 2 days to avoid cell membrane phospholipid degradation.8 Red blood cells were separated from plasma by centrifugation at 110 rcf for 5 min. Plasma was removed and 0.9% NaCl was added and centrifugal washing was repeated twice.

NaCl (>99% pure, Macron Chemicals, USA) solutions were used at 0.7% (hypotonic, 120 mM, 1.15 ± 0.05 S/m), 0.9% (isotonic, 154 mM, 1.5 ± 0.1 S/m), and 4% (hypertonic, 685 mM, 3.6 ± 0.2 S/m). NaCl was utilized because the hydrated cation (360 pm) and anion (330 pm) are similar in size with opposite, yet equal charges. Solution pH was adjusted between 6.9 and 7.1 using 1M NaOH (Sigma Aldrich, USA) and 1M HCl (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Isotonic solution was utilized as the medium for all experiments except for the controls noted. Dextrose (>99%, Fisher Scientific, USA) was utilized to maintain medium tonicity while alternating initial ionic concentration and conductivity (0.09% NaCl, 4.5% dextrose was 0.145 ± 0.005 S/m).

Red blood cell experiments

Dilutions of 1:400 red blood cells to isotonic NaCl solution were loaded into the device via the ports seen in Figure 1a. The device was mounted on the microscope stage and pressure between ports allowed to equilibrate for 15 min. AC signals ranging in amplitude of 10, 12.5, 15, and 17.5 Vpp and frequency of 250 kHz, 500 kHz, 750 kHz, and 1 MHz were applied via an Agilent 33250A waveform generator across the point electrode (Vpp sin(ωt)) and the flat electrode (grounded). Microscopy videos at 63× magnification were recorded at 1 fps for 10 min with the first 5 s without applied field to confirm cell healthiness. Each experiment was repeated three or more times.

To ascertain the effects of field gradient and potential AC electroporation as well as temperature and pH impacts on cell crenation, 100 μm gap parallel electrodes at 500 kHz and 15 Vpp were compared to the perpendicular electrode results. Medium conditions from 0.9% NaCl to 0.09% NaCl/4.5% dextrose were used with both perpendicular and parallel electrode devices to explore electroporation impact on cell crenation.

Flow measurements

ACEO and ACET flows, when present within the device and dominating DEP phenomena,17 were quantified by position/time tracking of 1 μm fluorescent latex beads (excitation ∼470 nm, emission ∼505 nm, Sigma Aldrich) mixed 1:130 with 0.9% NaCl. 63× magnification video was recorded at 3 fps.

Data analysis

Red blood cell areas were measured using edge detection software (Zeiss AxioVision 4.8) to identify cell perimeter and thus calculate 2D area. For a single cell, measurement error for n ≥ 5 analysis attempts was within 3%. Measured cell areas for 200 to 300 cells in each of 3 separate experiments were compiled into histograms and the average change in cell area percentage was obtained from the following equation:

| (2) |

where and are average cell areas at times t and 20 s. Error bars were determined as the standard error of one standard deviation from the mean.

ACET flow velocities were obtained via particle tracing. Curves following particle streak lines were drawn with Zeiss AxioVision software assistance. Path length of the curve per frame at a rate of 3 fps enabled the flow velocity to be calculated via path length/(number of frames/3 fps).

COMSOL Multiphysics (Burlington, MA) was utilized to map 2D electric field distribution and ion motion. Microdevice geometry shown in Figure 1 was duplicated within COMSOL with No Flux boundary conditions set for the PDMS walls and Electric Potential boundary conditions set for the electrodes ( for the vertical electrode and 0 for the horizontal electrode, where and ω = 2πf = 3.14 × 106 at 500 kHz). Electrostatics physics employing the Poisson equation was utilized within the AC/DC Module. The Nernst-Planck equation was utilized within the Chemical Reaction Engineering Module to obtain ion concentration behaviors over the first 100 periods. Also, solution properties were set according to 0.9% NaCl (0.145 M, relative permittivity = 77.15).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Control experiments were first completed to qualify red blood cell size and shape in hypo-, iso-, and hyper-tonicity solutions. Next, isotonic red blood cell areas were measured before and during nonuniform AC field experiments; cell crenation was compiled with time and spatial position in the electric field at each fixed signal frequency and amplitude. Competing effects were systematically explored and included electrothermal flow, temperature changes, pH, and electric field.

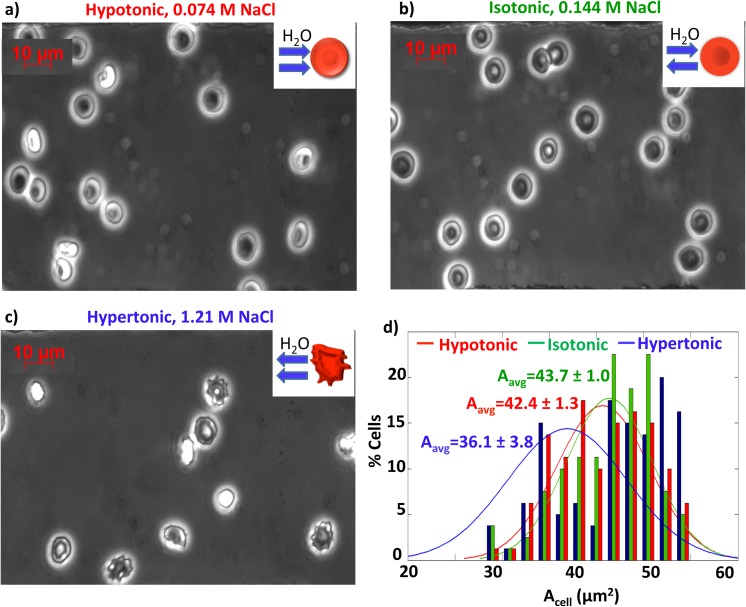

RBCs in controlled tonicity media

RBCs in 0.7%, 0.9%, and 4% NaCl with osmotic pressures of 233, 300, and 1333 Osm (hypo- iso- and hyper-tonic, respectively), were imaged and analyzed as shown in Figures 2a, 2b, 2c. Cells in hypotonic media (Fig. 2a) gain water changing to a spherical shape that equilibrates interior cell osmotic pressure with the lower external osmotic pressure. Cells in isotonic NaCl (Fig. 2b) remained biconcave in shape. In hypertonic solutions (Fig. 2c), the red blood cells lose water, shrink and demonstrate the characteristic crenated shape. Two-dimensional cell areas and standard deviations from n = 5 experimental repeats at each concentration were calculated and are compiled in Figure 2d. A disadvantage of the 2D analysis is that cells, which swell in 3 dimensions under hypotonic conditions, do not show an appreciably changed 2D area. In hypertonic conditions, decreases in cell area can be a result of either cell shape changes from biconcave to spherical or cell crenation. Increases in 2D cell area can result from a loss of cell water that flattens the biconcave shape making the 2D area appear to slightly increase. Size polydispersity thus substantially increased for cells in hypertonic conditions due to these differing tonicity crenation thresholds for individual cells (Figure 2c). This is expected in red blood cell populations diverse in cell age and bone marrow growth variations.

Figure 2.

Red blood cells at 63× in (a) hypotonic solution at 0.72% NaCl, (b) isotonic solution at 0.9% NaCl, and (c) hypertonic solution at 7% NaCl. (d) Cell area distribution obtained from image analysis corresponding to hypotonic (red), isotonic (green), and hypertonic (blue) solutions. Cell deformation and crenation due to the hypertonic solution are observed and reflected in area analysis.

Time dependence of RBC crenation in non-uniform AC fields

Washed red blood cells in 0.9% NaCl were observed under 10 to 17.5 Vpp, and 250 kHz to 1 MHz sinusoidal AC signals applied across the perpendicular electrode configuration shown in Figure 1 to create non-uniform electric fields. The original cell area and healthiness was assessed for 5 s before the field was applied. Red blood cell translational motion (due to DEP) and crenation behaviors were observed for 10 min.

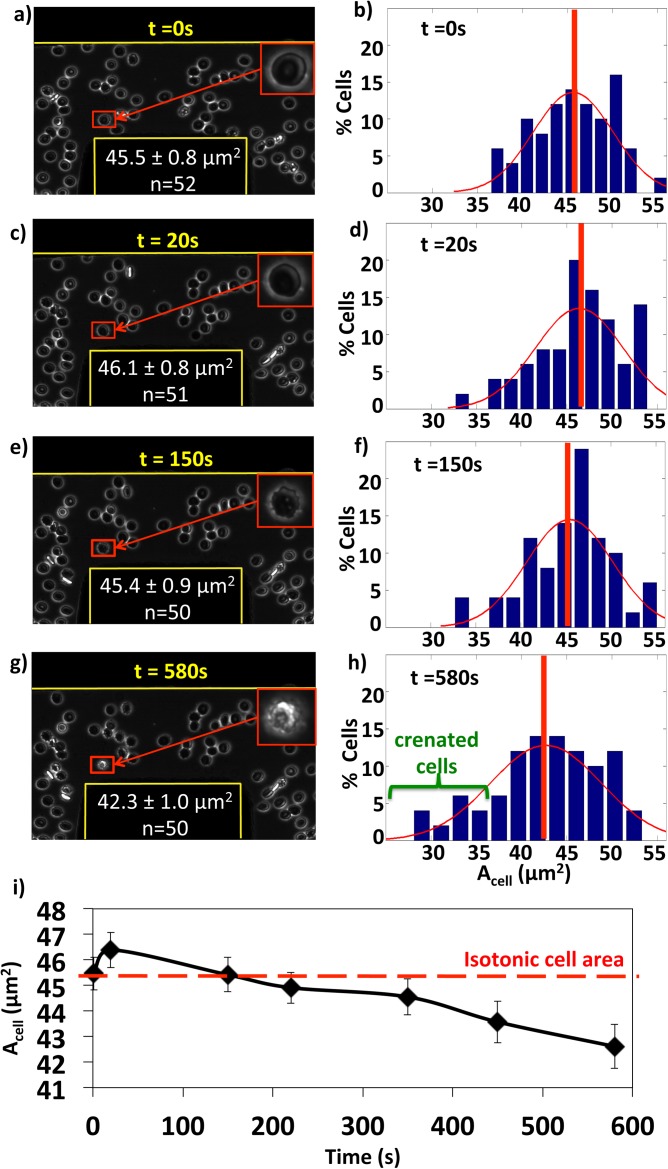

Microscopic images at 63× of the video region for an applied voltage of 15 Vpp and 500 kHz are shown in Figure 3 at (a) t = 0 s, (c) 20 s, (e) 150 s, and (g) 580 s, each with an enlarged single cell in the inset. Cell areas at each time were compiled into histograms with the size distribution curve overlaid and average shown by the vertical line as shown in Figures 3b, 3d, 3f, 3h. The progression of the average cell area over time is shown in Figure 3i. Cells first align and roll due to the DEP force while maintaining their biconcave shape (Figures 3a, 3b, 3c, 3d). However, beginning at 150 s (Figure 3e) at distances greater than 30 μm from the electrodes, cells progressively shrink and crenate as demonstrated by inset cell images in Figures 3e, 3g as well as the corresponding histograms showing the increased number of cells below 35 μm2. The histograms illustrate the decline in number of cells in the mid range from 40 to 50 μm2 and an increase in the number of cells at the smaller crenated size and a small increase above 50 μm2; combined, this generates a shift to smaller mean cell size area (Figure 3i) and an increase in polydispersity as was seen in Figures 2c, 2d for hypertonic media conditions.

Figure 3.

Time series of red blood cell crenation behaviors in 0.9% NaCl solution at a 500 kHz 15Vpp applied potential at (a) 0 s, (c) 20 s, (e) 150 s, and (g) 580 s. The corresponding cell area histogram and distribution traces at the same time points (b), (d), (f), and (h). (i) Average cell areas decrease as a function of time with error bars showing standard deviations. Cells begin to crenate at 150 s in (e) as illustrated by the magnified insets and in the corresponding median shifts of the histogram distributions.

Peak-to-peak potential and frequency dependence

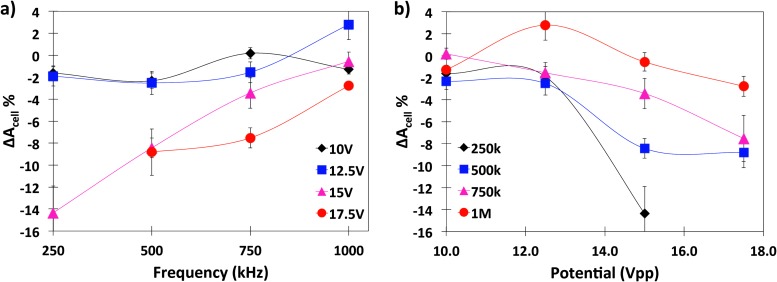

The peak-to-peak potential and frequency dependence of cell crenation at t = 580 s was quantified for 10.0, 12.5, 15.0, and 17.5 Vpp with corresponding electric fields of 0.100, 0.125, 0.150, and 0.175 V/μm at 250 kHz, 500 kHz, 750 kHz, and 1.00 MHz as illustrated in Figure 4. Cell area changes were calculated according to Eq. 2 with standard deviations calculated from n ≥ 3 experiments.

Figure 4.

(a) Frequency dependence of the percent change of cell 2D area at 10 Vpp (black), 12.5 Vpp (blue), 15 Vpp (pink), and 17.5 Vpp (red). Lines are provided only to guide the eye. (b) Potential dependency of percent change of cell 2D area at 250 kHz (black), 500 kHz (blue), 750 kHz (pink), and 1 MHz (red). Cell crenation increases with peak-to-peak potential and decreases with frequency.

Figure 4a demonstrates the potential dependency of cell crenation from 10.0 Vpp to 17.5 Vpp at frequencies from 250 kHz to 1.00 MHz. At 15.0 and 17.5 Vpp for all frequencies, cell crenation increased with decreasing frequency with a maximum measured area decrease of 13% for 250 kHz and statistically negligible at 1.00 MHz. As shown in Figure 4b, cell crenation increased (more negative ΔAcell %) with increasing electric field strength. At frequencies approaching 1.00 MHz, flow recirculation interfered with the Vpp trends. At 250 kHz and potentials at or above 17.5 Vpp, electrolysis reactions occurred at the electrodes and interfered with cell observation. Figure 4b illustrates that at 10.0 Vpp, cell areas were nearly constant at all frequencies and at 12.5 Vpp, cell areas increased slightly with field application. Error bars illustrate these changes are not statistically significant. However, at frequencies beyond 500 kHz at the highest potentials, the effect of ACET flow became more prominent as discussed in Sec. 3F and interfered with crenation behaviors.

Quantification of potentially competing mechanisms

Red blood cells have been observed in prior work to exhibit crenation changes induced by electroporation,16 medium solution pH,13 temperature value,14 and rapid temperature changes.15 Thus, controls were conducted for each of these factors. To avoid cell health factors, experiments were only conducted on visually healthy cells with average areas between 31.93 and 51.73 μm2, which is consistent with published normal 2D cell area ranges of 30.17 to 52.78 μm2.18

Impact from electric potential and field

Electric field impact on cell membrane

Electric fields can impact cell shape via dielectrophoretically driven alignment with the field (i.e., cell elongation) and electroporation yielding either reversible or irreversible membrane pores. The former, DEP, has a dielectric relaxation timescale on the order of microseconds for red blood cells in this frequency range19 and is a rapid response force causing realignment and cell rolling along the field lines. This effect is observed in Figure 3f at 20 s and does not account for the crenation observed at longer time scales (t > 150 s). The later, electroporation, can cause crenation-like cell shape changes similar to our results demonstrated in Figure 3.16 Electroporation is due to electric field induced membrane perturbations that cause nanopores to form and ease ion/water exchange, thus resulting in cell dehydration, crenation, and ghosting.20

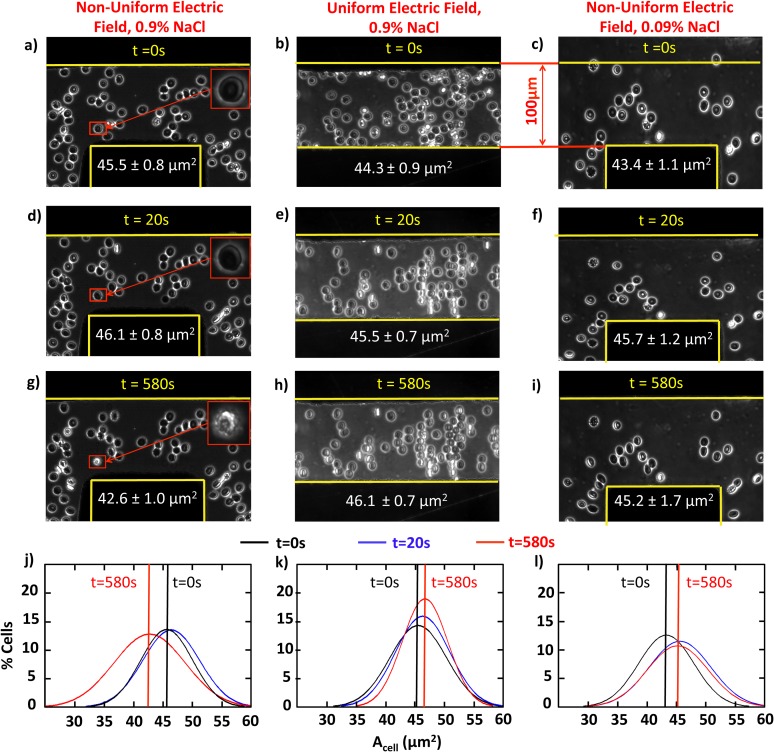

In order to test whether electroporation was responsible for crenation, the same red blood cell solution and field conditions were tested, as shown in Figure 5, in a perpendicular (first column) and parallel electrode (second column) configuration. Electroporation depends upon field strength, but not field gradients.21 Comparison of images at 580 s in Figures 5g, 5h, as well as the corresponding cell area size distributions in Figures 5j, 5k illustrates that crenation was not observed in the parallel electrode configuration at the same field and medium conditions as in the non-uniform case.

Figure 5.

Non-uniform/uniform electric field and high/low ion concentration comparison experiments at 500 kHz, 15 Vpp. The first column illustrates (a) 0 s, (d) 20 s, and (g) 580 s red blood cell behaviors in non-uniform electric fields. The second column illustrates the same experiment in uniform electrode configuration. While the third column uses a medium solution with 0.09% NaCl and 4.5% dextrose in non-uniform electric fields. The fourth row contains histograms of t = 0 s (black), 20 s (blue), and 580 s (red) for these three conditions. Cell crenation is observed in non-uniform electric fields at high ion concentrations, but not in uniform electric fields or low ion conditions.

Further, in the literature, no evidence of red blood cell electroporation has been reported for our conditions between 10.0 to 17.5 Vpp and 250 kHz to 1.00 MHz frequency. Electroporation on red blood cells has been observed in (a) 100 kHz sinusoidal frequency and 4–5 kV/cm potentials,21 (b) 0.02 to 0.08 ms pulse signals at 4–5 kV/cm,14 and (c) 100, 200, and 300 ms pulse signal at 1–1.6 kV/cm.22 Moroz et al.23 reported electroporation using a similar 0.9% NaCl medium with the application of 9 ms pulse signal at 1.7 kV/cm. Further, electroporation is highly dependent on signal duration,24 decreasing at higher frequencies and shorter signal durations. Our work used much smaller sinusoidal signals of 0.710 to 1.24 kVrms/cm and much shorter frequency perturbations than are insufficient for electroporation.

Electroporation also decreases with increasing conductivity25 and ion concentration26 due to the decreasing electroporation current described by26

| (3) |

where is pore radius, F is Faraday's constant, h is membrane thickness, and are diffusion coefficient and valence of free ions, respectively, while and are ion concentration inside the cell and outside the cell. A and B are constants.

In order to test the medium conductivity dependence of electroporation effects, comparison experiments were conducted using 0.09% NaCl and 4.5% dextrose at a final conductivity of 0.14 S/m as shown in Figures 5c, 5f, 5i, 5l. Solution osmolarity was maintained with neutrally non-charged dextrose and ionic NaCl, such that lower ionic concentrations (0.0154 M NaCl or 90% fewer ions) had a greater chance of yielded electroporation; no cell electroporation or crenation was observed at the same electric field condition of 500 kHz and 15 Vpp. Cells aligned with the electric field from t = 0 to 20 s, but no cell crenation was observed at 580 s as shown in Figure 5i and the red cell area distribution in Figure 5l. The neutral non-charged dextrose does not electromigrate, react or subsequently propagate spatially within the electric field; dextrose concentrations remain constant. Thus, Figure 5 data illustrate that ion presence in solution in addition to non-uniform electric field geometry are both important and necessary for cell crenation behavior. Further, the electroporation mechanism does not account for the observed red blood cell crenation.

Solution pH

Human red blood cells are reported to be morphologically stable within 1 unit change of pH for neutral 7.0.13 In DC microfluidic systems, electrochemical reactions, primarily water electrolysis can create microscale pH gradients.27 Threshold electrochemical potentials with respect to a standard hydrogen electrode are 0 V for reduction reactions at the anode and 1.23 V for oxidation reactions at the cathode. Changes in pH have only been reported at very low frequencies.28, 29 To the best of our knowledge, the highest frequency reporting pH altering effects was in a 10 kHz AC electric field at potentials up to 20 Vpp.17 The pH change was much less than 1 unit and the authors concluded this was negligible given the sensitivity of their fluorophore measurement tool.17 The lowest frequency examined in our current work was 250 kHz and the maximum potential was 17.5 Vpp. Reaction rate changes inversely with frequency30 so electrochemical reactions are unlikely to influence medium compositions at higher frequencies.

To experimentally verify whether electrolysis reactions could be a factor in crenation, re-examination of the 100 μm perpendicular and parallel electrode experiments in Figure 5 are insightful. At the same electrolyte solution, 0.9% NaCl, and electric potential, 15 Vpp, electrochemical reactions are equally probable in both the non-uniform and uniform electric fields. However, no cell crenation was observed in the parallel electrode system (second column with Figs. 5b, 5e, 5h) and no significant peak shift was quantifiable in Fig. 5f. Thus, pH shifts due to electrolysis are unlikely and do not account for the crenation observed.

Absolute temperature value and change temperature in media

The passage of current through conductive liquids raises temperatures via Joule-heating.31 Both high absolute temperatures and rapid temperature changes have been shown to lead to cell deformation.14, 32, 33 Although both mechanisms exist in our system, neither of them is significant enough to induce observable cell crenation.

Increases in medium temperatures, T, can create osmotic pressure differences () via the colligative effect induced by the equilibrium between medium and cell cytosol water chemical potential. This mechanism occurs over time-scales on the order of hours32, 33

| (4) |

where TTP is temperature-time product , is temperature difference (, and t is the operation time (h). To estimate the temperature difference, Joule heating temperature jumps in a parallel electrode system can be estimated via31

| (5) |

where for the conditions examined, the maximum root mean square potential is aqueous thermal conductivity is k = 0.58 W/(mK), and conductivity is , which predicts . This prediction does not account for thermal dissipation through the glass bottom and the PDMS sides and top. TTPs greater than 48 are required for noticeable cell membrane perturbations.32, 33 In our system, the maximum possible temperature change noted above is 12.4 °C and the operation time is 10 min leading to TTP ≈ , which is insufficient to generate a noticeable osmotic pressure difference, , or crenation.

Second, rapid temperature jumps of 2 °C or greater in 2 μs can induce thermal osmosis, which imbalances chemical potentials causing hemolysis.15 A 0.01 °C temperature difference was shown to induce a 1.3 atm pressure difference yielding crenation.15 An order of magnitude time, estimate to reach thermal equilibrium31 can be obtained from

| (6) |

with medium density , heat capacity , and minimum length scale , to yield 105 μs. Thermal hemolysis is induced 3 orders of magnitude slower at 100 μs.15 Thus, temperature jumps sufficient to induce cell osmotic pressure shifts are not possible at our conditions within the microdevice.

To experimentally verify whether Joule heating could yield absolute temperatures or rapid temperature jumps leading to crenation, the same 100 μm gap parallel electrode experiments were conducted with highest ionic condition of 0.9% NaCl solution at a Vrms of 6.19, which should induce the largest heat generation, and most rapid temperature jump. The data were very similar to Figures 5b, 5e, 5h, 5k which demonstrate no cell crenation. Thus, neither the absolute temperature nor the temperature jump is the mechanism inducing cell deformation.

Discussion

Spatially non-uniform AC fields were shown to induce red blood cell crenation under isotonic conditions with higher medium ion conductivities. Crenation was assessed by quantifying 2D cell area. Crenation was greatest at lower frequencies near 250 kHz and became less pronounced as frequencies approached 1.00 MHz. Higher potentials up to 17.5 Vpp yielded the greatest crenation. None of the competing mechanisms (electroporation, pH, absolute temperature, or temperature jump) showed comparable crenation to the non-uniform electric field results from Figure 3. As a result, competing mechanisms were found to be insufficient at the medium, electric field and microdevice conditions employed here to account for the crenation observed at tens of μm from the electrode surfaces.

To explain the demonstrated time sequence for cell crenation, the lack of crenation in all uniform field experiments as well as the potential and frequency dependence, our initial hypothesis is that local solution ion concentration changes from isotonic to hypertonic via ion electromigration unevenly biased by the spatially non-uniformities of the electric field.

Physical reasoning behind the ion concentration gradient hypothesis

For an ion concentration gradient to form and induce local solution tonicity changes, the ion flux must be unbalanced. Ion flux depends upon ion electromigration, diffusion, convection, and reaction34 so ion concentration with time is

| (7) |

Each ion transport mechanism is discussed separately below:

-

1.

The second term on the right hand side, diffusion, is a passive process driven by concentration gradients, and in a simple salt solution with only one cation and one anion (NaCl), this mechanism cannot actively initiate a biased propagation of ions in an initially uniform concentration. Once a concentration gradient is established, diffusion would counter this and push the system to a uniform concentration.

-

2.

Convection is the third term on the right hand side. Electric field induced ACEO and ACET flows are sources of convection in this otherwise stationary system. In our high conductivity and higher frequency experimental conditions, ACEO was not observed and can be reasonably neglected. However, ACET was observed. This mechanism is caused by local Joule heating of the fluid under high frequency, high potential conditions. Local heating alters local fluid density, viscosity, conductivity, and electric permittivity. The spatially nonuniform fluid properties then induce ACET flow.35, 36 Fluorescent latex beads (1 μm) were used to image and estimate fluid flow as shown in Table TABLE I.. The velocity and flow pattern area increased with increasing frequency, verifying that our applied potentials fall in the permittivity dominant regions for ACET flow. The frequency dependencies of ACET velocities in Table TABLE I. and of cell crenation in Figure 4 are in opposition. Cell crenation becomes less prevalent while ACET becomes more pronounced with increasing frequency. Over small length scales, ACET flows would smooth any developing ion concentration gradients, and thus reduce the prevalence of red blood cell crenation.

-

3.

Reactions or Faradaic charging, fourth term in Eq. 7, can induce bulk concentration changes which induce ACEO reversal37 at electrode charging frequencies less than 100 kHz calculated from .37 However, experimental conditions presented here are greater than 250 kHz where the reaction rate is not significant and the electric double layers cannot be established on electrode surfaces.38 Further, Figure 5 comparison experiments using parallel electrodes corroborate this conclusion. Any electrode reactions/Faradaic charging would be the same or even larger for parallel electrodes than for orthogonal electrodes due to slightly greater parallel electrode surface areas. This is not observed. Thus, electrode reactions/Faradaic charging mechanisms are not responsible for the ion concentration gradients formed.

-

4.

Electromigration is an electrical force-induced motion of ions. Figure 5 illustrated cell crenation in non-uniform fields but not in uniform electric fields. Red blood cells crenate in response to local medium hypertonicity, which indicates local ion concentration gradients in non-uniform electric fields, but not in uniform electric fields. Thus, we hypothesize that local ion concentration gradients are induced by gradients in the electric field. For the red blood cells, the osmotic pressure change could be induced by local ion accumulations resulting from unequal ion migration that is a direct result of the AC electric field non-uniformity. According to the resistor-capacitor (RC) model of the electric double layer, the potential drop across the electric double layer is finite at >100 kHz as the electrode charging time is 39 so the electrode is not fully screened and the potential drop across the bulk fluid is not infinitely small. At this quasi-steady state condition, the time average ⟨⟩ = 0 in Eq. 7 results in = if we neglect the convection term and reaction term as discussed in #2 and #3 above.

TABLE I.

Frequency dependence of induced ACET flow velocities at Vpp = 15.

| Frequency (kHz) | 250 | 500 | 750 | 1000 | 10 000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured velocity (μm/s) | 1.7 | 2.2 | 26 | 30 | 60 |

Experiments indicate cell crenation is induced in ionic solution by the nonuniformities in AC electric fields. Based on the term-by-term discussion in #1 through #4, one can neglect convective flow, reaction, and ion-ion interactions in a preliminary hypothesis regarding the causes of the red blood cell crenation. Since the fluid is nearly stagnant for much of the frequency/potential space explored, Stokes drag on the small hydrodynamic radius of the ions would be the same everywhere. We thus speculate that cell crenation is caused by ion concentration gradients induced by high frequency, non-uniform electric fields.

Since the lowest frequency we applied was 250 kHz, corresponding to for one period, and 39 are required for electrode charging time, there is not sufficient time to establish the electric double layer and the electrode is not fully screened. In the presence of an ion concentration gradient, diffusion, would not be constant. The diffusion coefficient for Na+ is ∼while Cl- is . Thus, diffusion time is ∼8 s across the 100 μm electrode gap, which is also much longer than the s electric field period. This means that electric field driven ion electromigration could dominate ion motion.

Poisson's equation, , which relates the potential, φ, to net charge density, ρ, and constant dielectric permittivity, ε, is used to describe systems with significant deviations from electroneutrality.40 The experimental evidence presented suggests that ion migration due to the electric field, and to a lesser degree due to differences between Na+ and Cl- diffusivity, accumulates over AC cycles causing deviations from electroneutrality and eventually becoming apparent via cell crenation after roughly 108 cycles.

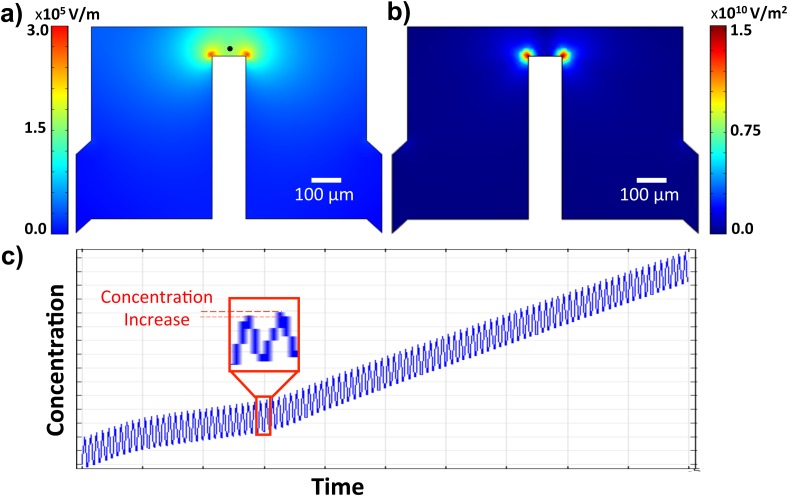

As a preliminary test of this hypothesis, COMSOL's electrostatics module was first used to simulate the electric field strength within the microdevice as shown in Figure 6a at 15 V assuming relative permittivity of 77.15 for 0.9% NaCl. The corresponding electric field gradient is shown in Figure 6b. Once converged, additional physics was added via the Nernst-Planck module at 500 kHz. The traditional electroneutrality assumption was not imposed. Diffusion, convection, and reaction terms were all neglected by assuming and . Due to the spatially non-uniform electric field, the electric field strength varies as a function of geometric position, which yields a non-zero term in Eq. 7. Figure 6c shows ion concentration oscillations at a single point 20 μm from the orthogonal electrode (black dot, Figure 6a) in the nonuniform AC electric field. The net ion flux oscillates with the field such that ion concentration accumulates slowly over the first 100 periods (computational limitation).

Figure 6.

(a) Spatial variation of the electric field showing highest electric fields (red) near the vertical electrode. (b) Electrical field gradient showing the highest gradient at the vertical electrode. (c) COMSOL simulation of first 100 cycles of 15 Vpp applied 500 kHz AC potential showing the oscillation of the ion concentration. Ion concentration increases slightly with each period and accumulates over time.

For the quasi-equilibrium condition, , Eq. 7 can be rewritten as

| (8) |

The right hand side of Eq. 8 is the non-zero electrochemical potential induced by gradient of electric field shown in Figure 6b. This electric field non-uniformity yields a nonzero and thus a nonzero ion concentration gradient. Since the diffusion time scale is 6 orders of magnitude slower than ion electromigration due to the electrochemical potential term, increases are seen in local ion concentration in the COMSOL simulation. This is attributed as the reason that the local osmotic pressure is altered from isotonic to hypertonic thus creating cell crenation.

In the context of this hypothesis, Figure 5 compared two initially isotonic solutions: the first column is 0.9% NaCl, while the third column is a mixture of 0.09% NaCl and 4.5% dextrose (nonionic). The applied potential, is identical in these experiments, so electromigration for a single ion would be the same and so would the counteracting diffusion . However, the initial ion concentration is much lower in the 0.09% NaCl media, so the induced ion concentration, , is not significant enough to induce noticeable cell crenation. While the availability of ions exists in the parallel electrode experiment in column two of Figure 5, there is no spatial nonuniformity in the electric field so the term is net zero and no concentration gradient develops.

Further, the peak-to-peak potential dependence presented in Figure 4b illustrates that as increases, , , and F are constants, and the non-uniformity of electric field causes the ions to accumulate faster over a larger 2D area thus inducting crenation in more red blood cells.

The whole process for ion concentration gradient establishment occurs gradually and thus the osmotic pressure differences between the red blood cell interior and exterior would also change gradually. However, membrane deformation to a crenated state is a threshold phenomenon requiring a sufficient osmotic pressure difference (i.e., tonicity difference) to change. This threshold is not identical for all cells in a red blood cell population due to slight morphological and phenotypical differences. The measurable cell crenation observed in Figure 3 initiates around 150 s with cell crenation first occurring closer to the high field density signal electrode and progressing up to ∼60 μm from the electrode edge. The electrical double layer takes ∼10−4 s to develop in 0.9% NaCl ion concentrations and its length would be 1 μm or less. The length and time scales over which crenation was observed are not consistent with an electrical double layer-driven mechanism.

The results compiled in Figure 4 indicate that greater crenation occurs above 12.5 Vpp and below 750 kHz. These conditions favor ion concentration establishment and yield larger solution tonicity changes. However, these results are bounded by competing mechanisms. At higher frequencies, electrothermal flows cause mixing, thus preventing sufficient local increases in ion concentration. At lower frequencies, but higher potentials, electrolysis reactions at the electrode surfaces dominate and gas bubbles consume the chamber.

CONCLUSIONS

This work experimentally examined the time dependence of cell crenation in a spatially non-uniform AC field. Crenation was observed at distances of 10 to 60 μm, larger than any possible electrode double layer, starting at time scales over 150 s. Potential and frequency dependences were examined and an increase in cell crenation was observed with potential increases and a decrease in crenation was observed with frequency increases.

The possible physical mechanisms for cell crenation were systematically examined via uniform and non-uniform electric field and high/low ion concentration comparison experiments. Cell deformation due to pH change, temperature, temperature change, and electroporation were excluded by these comparison experiments and by a term-by-term examination of the ion flux equation. We thus advance an initial hypothesis that cell crenation is caused by medium tonicity changes occurring via induced electromigration from the electric field gradient, which causes ion concentration gradients in the spatially non-uniform AC electric fields. Further, more rigorous theoretical analysis is required to test and improve this initial hypothesis.

These ion concentration gradients occur over large length scales, which are much greater than the electrode double layer Debye length, and at long time scales. This is in contradiction to the general assumption that ion concentration remains spatially uniform at the high frequency AC fields typically used in dielectrophoretic experiments and contrary to the electroneutrality assumption typically employed for theoretical explorations in these systems. These induced ion concentration gradients will influence local electrical conductivity, density and other fluid properties and may account for anomalous fluid behaviors and particles responses sometimes observed in these microdevices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was partially supported by National Science Foundation Grant No. CBET 1041338.

Paper submitted as part of a special collection covering contributions related to the American Electrophoresis Society's symposium at the SciX 2013 meeting (Guest Editors: A. Ros, E.D. Goluch) held in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, September 29–October 4, 2013.

References

- Arya S. K., Lee K. C., Bin Dah'alan D., Daniel , and Rahman A. R. A., “Breast tumor cell detection at single cell resolution using an electrochemical impedance technique,” Lab Chip 12, 2362–2368 (2012). 10.1039/c2lc21174b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapizco-Encinas B. H., Simmons B. A., Cummings E. B., and Fintschenko Y., “Dielectrophoretic concentration and separation of live and dead bacteria in an array of insulators,” Anal. Chem. 76, 1571–1579 (2004). 10.1021/ac034804j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medoro G., Manaresi N., Leonardi A., Altomare L., Tartagni M., and Guerrieri R., “A lab-on-a-chip for cell detection and manipulation,” IEEE Sens. J. 3, 317–325 (2003). 10.1109/JSEN.2003.814648 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler S., Shirley S. G., Schnelle T., and Fuhr G., “Dielectrophoretic sorting of particles and cells in a microsystem,” Anal. Chem. 70, 1909–1915 (1998). 10.1021/ac971063b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne P. R. C., Wang X. B., Huang Y., and Becker F. F., “Dielectrophoretic separation of cancer cells from blood,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 33, 670–678 (1997). 10.1109/28.585856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minerick A. R., “The rapidly growing field of micro and nanotechnology to measure living cells,” AIChE J. 54, 2230–2237 (2008). 10.1002/aic.11615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minerick A. R., Zhou R. H., Takhistov P., and Chang H. C., “Manipulation and characterization of red blood cells with alternating current fields in microdevices,” Electrophoresis 24, 3703–3717 (2003). 10.1002/elps.200305644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K. M. and Minerick A. R., “Explorations of ABO-Rh antigen expressions on erythrocyte dielectrophoresis: Changes in cross-over frequency,” Electrophoresis 32, 2512–2522 (2011). 10.1002/elps.201100077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S. K., Artemiou A., and Minerick A. R., “Direct current insulator-based dielectrophoretic characterization of erythrocytes: ABO-Rh human blood typing,” Electrophoresis 32, 2530–2540 (2011). 10.1002/elps.201100089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulati G., Blood Cell Morphology Grading Guide (American Society for Clinical Pathology (ASCP) Publishing Team, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Rasia M. and Bollini A., “Red blood cell shape as a function of medium's ionic strength and pH,” Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 1372, 198–204 (1998). 10.1016/S0005-2736(98)00057-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer T. M., “Shape memory of human red blood cells,” Biophys. J. 86, 3304–3313 (2004). 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74378-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gedde M. M., Yang E. Y., and Huestis W. H., “Shape response of human erythrocytes to altered cell pH,” Blood 86, 1595–1599 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinosita K. and Tsong T. Y., “Formation and resealing of pores of controlled sizes in human erythrocyte-membrane,” Nature 268, 438–441 (1977). 10.1038/268438a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsong T. Y. and Kingsley E., “Hemolysis of human erythrocyte induced by a rapid temperature jump,” J. Biol. Chem. 250, 786–789 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movahed S. and Li D. Q., “Microfluidics cell electroporation,” Microfluid. Nanofluid. 10, 703–734 (2011). 10.1007/s10404-010-0716-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Sanchez P., Ramos A., Gonzalez A., Green N. G., and Morgan H., “Flow reversal in traveling-wave electrokinetics: An analysis of forces due to ionic concentration gradients,” Langmuir 25, 4988–4997 (2009). 10.1021/la803651e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon M. L., Clinical Hematology: Theory and Procedures (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004), p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Adams T. N. G., Leonard K. M., and Minerick A. R., “Frequency sweep rate dependence on the dielectrophoretic response of polystyrene beads and red blood cells,” Biomicrofluidics 7, 064114 (2013). 10.1063/1.4833095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBruin K. A. and Krassowska W., “Modeling electroporation in a single cell. I. Effects of field strength and rest potential,” Biophys. J. 77, 1213–1224 (1999). 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76973-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D. C. and Reese T. S., “Changes in membrane-structure induced by electroporation as revealed by rapid-freezing electron-microscopy,” Biophys. J. 58, 1–12 (1990). 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82348-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao N., Le T. T., Cheng J. X., and Lu C., “Microfluidic electroporation of tumor and blood cells: Observation of nucleus expansion and implications on selective analysis and purging of circulating tumor cells,” Integr. Biol. 2, 113–120 (2010). 10.1039/b919820b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroz V. V., Chernysh A. M., Kozlova E. K., Borshegovskaya P. Y., Bliznjuk U. A., Rysaeva R. M., and Gudkova O. Y., “Comparison of red blood cell membrane microstructure after different physicochemical influences: Atomic force microscope research,” J. Crit. Care 25, 539.e1 (2010). 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilska A. O., DeBruin K. A., and Krassowska W., “Theoretical modeling of the effects of shock duration, frequency, and strength on the degree of electroporation,” Bioelectrochemistry 51, 133–143 (2000). 10.1016/S0302-4598(00)00066-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djuzenova C. S., Zimmermann U., Frank H., Sukhorukov V. L., Richter E., and Fuhr G., “Effect of medium conductivity and composition on the uptake of propidium iodide into electropermeabilized myeloma cells,” Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 1284, 143–152 (1996). 10.1016/S0005-2736(96)00119-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBruin K. A. and Krassowska W., “Modeling electroporation in a single cell. II. Effects of ionic concentrations,” Biophys. J. 77, 1225–1233 (1999). 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76974-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gencoglu A., Camacho-Alanis F., Nguyen V. T., Nakano A., Ros A., and Minerick A. R., “Quantification of pH gradients and implications in insulator-based dielectrophoresis of biomolecules,” Electrophoresis 32, 2436–2447 (2011). 10.1002/elps.201100090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng W. Y., Lam Y. C., and Rodriguez I., “Experimental verification of Faradaic charging in ac electrokinetics,” Biomicrofluidics 3, 022405 (2009). 10.1063/1.3120273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senftle F. E., Grant J. R., and Senftle F. P., “Low-voltage DC/AC electrolysis of water using porous graphite electrodes,” Electrochim. Acta 55, 5148–5153 (2010). 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.04.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allmand A. J. and Cocks H. C., “CCCXLVII.-The electrolysis of potassium chloride solutions by alternating currents,” J. Chem. Soc. (Resumed) 1927, 2626–2639. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A., Morgan H., Green N. G., and Castellanos A., “Ac electrokinetics: A review of forces in microelectrode structures,” J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 31, 2338–2353 (1998). 10.1088/0022-3727/31/18/021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Utoh J. and Harasaki H., “Damage to erythrocytes from long-term heat-stress,” Clin. Sci. 82, 9–11 (1992). 10.1042/cs0820009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowemimo-Coker S. O., “Red blood cell hemolysis during processing,” Transfus. Med. Rev. 16, 46–60 (2002). 10.1053/tmrv.2002.29404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman J. and Thomas-Alyea K. E., Electrochemical Systems (Wiley, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Lian M., Islam N., and Wu J., “AC electrothermal manipulation of conductive fluids and particles for lab-chip applications,” IET Nanobiotechnol. 1, 36–43 (2007). 10.1049/iet-nbt:20060022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon Z. R. and Chang H. C., “Electrothermal ac electro-osmosis,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 024101 (2009). 10.1063/1.3020720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez P., Ramos A., Green N. G., and Morgan H., “Traveling-wave electrokinetic micropumps: Velocity, electrical current, and impedance measurements,” Langmuir 24, 9361–9369 (2008). 10.1021/la800423k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahame D. C., “Electrode processes and the electrical double layer,” Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 6, 337–358 (1955). 10.1146/annurev.pc.06.100155.002005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan H. and Green N. G., AC Electrokinetics: Colloids and Particles (Research Studies Press Ltd., 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Deen W. M., Analysis of Transport Phenomena, 2 ed. (Oxford University Press, USA, 2011). [Google Scholar]