Abstract

Establishment of appropriate animal models is an important step in exploring the mechanisms of drug-induced ototoxicity. In the present study, using guinea pigs we compared cochlear lesions induced by cisplatin administered in two regimens: consecutive application alone and in combination with furosemide. The effects of furosemide alone were also evaluated; it was found to cause temporary hearing loss and reversible damage to the stria vascularis. Consecutive application of cisplatin alone appeared to be disadvantageous because it resulted in progressive body weight loss and higher mortality compared to the combined regimen, which used a smaller cisplatin dose. The combined regimen resulted in comparable hearing loss and hair cell loss but a markedly lower mortality. However, their coadministration failed to cause similar damage to spiral ganglion neurons (SGN), as seen in animals that received cisplatin alone. This difference suggests that the combined regimen did not mimic the damage to cochlear neuronal innervation caused by the clinical application of cisplatin. The difference also suggests that the SGN lesion is not caused by cisplatin entering the cochlea via the stria vascularis.

Keywords: totoxicity, cisplatin, furosemide, auditory brain-stem response, hair cell, spiral ganglion neuron

Introduction

Cisplatin (Cis) is a first-generation antineoplastic drug that is still frequently used in the clinic. Major side effects of this drug include ototoxicity, neurotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity (Strauss et al. 1983; Sastry and Kellie 2005; Meng et al. 2007). Cis has been demonstrated to injure cells and tissues by inducing apoptosis (Mares et al. 1986; Alam et al. 2000). Great efforts have been made to clarify the mechanisms of Cis ototoxicity, but exactly how Cis damages cochlear tissue remains unclear. Specifically, why terminally differentiated cochlear cells (cells that have exited the cell cycle) are killed by Cis, which is designed to kill mitotic cells, remains unknown, and why hair cells are more sensitive to Cis than other cell types is also unclear. Thus, further studies are needed to explore these issues, and such studies will likely be done in animal models, because of ethical considerations.

Rodents are commonly used in such studies due to their availability, low cost, and simpler genetic backgrounds. However, a major disadvantage of rodents is the high resistance of their cochleae to Cis damage. Several methods have been used to establish Cis ototoxicity in these animals, and the administration regimen is of great importance in efforts to effectively induce model cochlear lesions. A single high-dose Cis injection produces little hair cell damage, even at a dose that causes 50% mortality (Campbell et al. 1996). Consecutive injections over several days have been used in many reports as a way to induce cochlear lesions (Poirrier et al. 2010; Teranishi, Nakashima, and Wakabayashi 2001). However, this regimen may also result in rapid deterioration in the animals’ health and high mortality before any evident ototoxic effect is established (Ekborn et al. 2003; Von Hoff et al. 1979; Minami, Sha, and Schacht 2004).

To reduce mortality following Cis administration when establishing cochlear lesions, it is desirable to use an agent that can selectively enhance the effect of Cis in the inner ear (Gratton et al. 1990). Loop diuretics, including ethacrynic acid (EA) and furosemide, have synergistic interactions with Cis in the cochlea (Bates, Beaumont, and Baylis 2002; McFadden et al. 2004; Ding et al. 2007). These drugs cause temporary hearing loss, which manifests as limited, reversible threshold shifts up when administered alone (Anniko 1978; Rybak 1993). However, even a small amount of Cis can cause a significant hair cells lesion if it is combined with EA or furosemide (Komune and Snow 1981; Ding et al. 2007).

Previously, EA was often the loop diuretic of choice for this purpose (Komune and Snow 1981; Ding et al. 2007). However, this drug was recently discontinued, because the FDA withdrew its approval for use in humans. Additionally, EA must be administered intravenously, which is difficult in some animal species, such as guinea pigs. Furosemide is a diuretic that can replace EA in establishing ototoxicity in animal models. However, furosemide may not produce exactly the same outcome as EA. Thus, a comprehensive evaluation is necessary to validate the use of furosemide. There was no such report until recently, when a study in mice was published (Li et al. 2011). While the mouse study is important due to the obvious advantages of mouse models in hearing research, this evaluation should be duplicated in other species, such as guinea pigs, that are commonly used in ototoxicity studies. This species is favored by many researchers due to ease of handling and their relatively large cochleae, facilitating morphological evaluations.

While the coadministration of Cis with a diuretic drug facilitates the establishment of Cis-induced cochlear lesions, the possibility exists that the cochlear damage induced via different approaches may differ. In previous studies, even with the use of EA, such potential differences were not fully addressed.

In the present study, using guinea pigs we compared Cis-induced ototoxicity established via consecutive administration of Cis alone and one injection of Cis in combination with furosemide. We compared the advantages and disadvantages of the two methods and the induced cochlear pathologies in an attempt to validate the use of furosemide + Cis coadministration to establish a cochlear lesion model.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Groupings

In total, 73 Dunkin-Hartley guinea pigs, with body weights from 350 to 450 g, were obtained from the Experimental Animal Service of Shanghai Jiaotong University Medical School. This study was conducted in strict accordance with Declaration of Helsinki principles, and the protocol was approved by the Committee on Experimental Animal Services, Shanghai, China (permit number: SYXK [H2011-0128]).

The animals, which were maintained on a 12/12-hr light–dark cycle during the experiment, were randomly assigned to four groups: group 1 (n = 15) received furosemide alone (fur-alone group), group 2 (n = 11) received consecutive injections of Cis alone (Cis-alone group), and group 3 (n = 41) received a single injection of Cis in combination with furosemide (coadministration group); group 4 (n = 6) were normal controls. The animals in group 3 were further divided into subgroups according to the Cis dose and the time interval between the administration of Cis and furosemide (Table 1). Hearing status was monitored using a frequency-specific auditory brain-stem response (ABR) test before and at 0.5 hr, 1 hr, 2 hr, 4 hr, and 12 hr after drug administration in group 1 and at 7 days post drug application in groups 2, 3 and 4. Immediately after the final functional test, the animals were sacrificed and the cochleae were harvested for morphological observation. In each animal, 1 ear was used to generate a stretched preparation of the basilar membrane to observe the lesion in the organ of Corti, and cross sections were made of the other to observe damage to the spiral ganglion neuron (SGN) and stria vascularis.

Table 1.

Percentage OHC loss by group and anatomical location.

| Group

|

n | 1st Turn | 2nd Turn | 3rd Turn | 4th Turn | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cis dose | Interval | ||||||

| 3 mg/kg × 5 d | N/A | 11 (7) | 35.4 ± 4% | 11.8 ± 1.5% | 2.9 ± 1.3% | 1.9 ± 0.1% | 18 ± 2% |

| 0.1 mg/kg | 30 min | 7 (6) | 18.9 ± 1% | 10.9 ± 1% | 3.7 ± 1% | 1.1% | 11.6 ± 3% |

| 0.2 mg/kg | 0 min | 5 (4) | 2% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 min | 7 (6) | 90.8 ± 5% | 28.2 ± 4% | 9.2 ± 1% | 3.9 ± 1% | 45.6 ± 2.4% | |

| 60 min | 6 (6) | 89.9 ± 6% | 34.1 ± 4% | 8.6 ± 1% | 2.8% | 48.6 ± 3% | |

| 90 min | 8 (6) | 98.2 ± 2% | 45.5 ± 7% | 17.4 ± 3% | 5.3% | 56.2 ± 1% | |

| 2.0 mg/kg | 30 min | 8 (6) | 100% | 100% | 98.7 ± 1.2% | 78.8 ± 3.6% | 97.7 ± 2.8% |

Note. The percentage value was calculated as the result of lost OHCs divided by the total OHCs in the corresponding region. Furosemide was given at 200 mg/kg for all subgroups. n = sample size (survived animals). Interval is the time delay between furosemide and Cis administration.

ABR Test

All animals were tested under 40-mg/kg ketamine and 8-mg/kg xylazine anesthesia (i.p.). Body temperature was maintained at 38°C with a thermostatic heating pad. Acoustic stimuli were tone bursts (10 ms duration, 0.5 ms rise/fall, Blackman window) synthesized using the SigGen software (Tucker Davis Technologies [TDT], Alachua, FL), amplified using an SA1 audio amplifier and transduced by a broadband speaker (FT28D). The animal’s responses were detected using three subdermal electrodes, with noninverted at vertex, reference, and grounding electrodes behind two ears. The responses were collected using TDT hardware (RA16PA and BA) and software (BioSigRP), amplified by 20, filtered between 100 Hz and 3 kHz, and averaged 1,000 times. Test frequencies ranged from 1 to 32 kHz in octave steps. The stimuli were presented in a downward sequence (5-dB steps) at each frequency, starting at 90 dB until the threshold was approached. The threshold was defined as the lowest sound level at which a visible and repeatable ABR wave was seen.

Drug Administration

Consecutive Cis administration in the Cis-alone group (group 2) was conducted while the animals were awake. Cis (P4394; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was prepared in a 0.9% saline solution. A total dose of 15 mg/kg (i.m.) was given to each animal, divided evenly across 5 consecutive days. To administer furosemide (200 mg/kg i.m., cat. #5913020911; Webster Veterinary, Devens, MA) in groups 1 and 3, the animals were anesthetized with 8-mg/kg ketamine (i.p.) followed by 33-mg/kg pentobarbital sodium (i.p.) before the furosemide injection. This regimen kept the animals in deep anesthesia for 2.5 to 3.5 hr. The animals were laid on a thermostatic heating pad to maintain the body temperature at 37°C until they had recovered fully from the anesthesia. In group 3, different Cis doses were given (i.m.) at different time intervals after furosemide administration (Table 1).

Stretched Preparation

Animals were sacrificed with a pentobarbital sodium overdose (200 mg/kg, i.p.). In each animal, 1 ear was randomly selected for a stretched preparation, while the other was used for semi-thin cross sections. The temporal bones were harvested and each bulla was opened to expose the cochlea. The oval window and round window were opened. A small hole was made at the apex of the cochlea, through which fixative (4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS) was perfused. Then, the cochleae were submerged in the fixative for at least 4 hr. The basilar membrane was dissected out under a dissecting microscope and the tectorial membrane was then removed. To stain the organ of Corti with F-actin, the preparation was treated with a rhodamine phalloidin solution (P1951; Sigma) in the dark for 20 min at room temperature. The specimens were then rinsed 3 times with 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). Fluorescent hair cells were counted under an epifluorescence light microscope. The percentage hair cell loss in each 0.24-mm segment was calculated, and a cochleogram was made for hair cell loss as a function of cochlear length.

Semi-Thin Cross Sections

Cochleae were fixed in 2.5% glutaric dialdehyde for 4 hr at room temperature. Following several rinses with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), the modiolus was decalcified in 10% EDTA on a swing bed for 5 days at room temperature. Next, the specimens were post-fixed in 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 hr at 4°C. Dehydration was performed through a graded ethanol series, propylene oxide, and a series of ethoxyline resins. The modioluses were then embedded in the final resin overnight at 70°C. Semi-thin (1-μm) sections in the mid-modiolar plane were cut with diamond knives, collected on glass slides, stained with 1% methylene blue, and then rinsed 3 times with distilled water. The sections were subsequently examined and photographed under a light microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) for both qualitative and quantitative analysis of SGNs in Rosenthal’s canal from the first to the third turn. In each turn, SGNs were counted in 10 slices that were collected across a ~800-μm distance to get an average SGN number in each cross view of Rosenthal’s canal.

To observe the impact of furosemide on the cochlear lateral wall, the spiral ligament and affiliated stria vascularis (SV) were dissected and decalcified for 1 day; the rest of the process was similar to that described above for SGN lesion observation. The samples in experimental groups (groups 1–3) would be compared against those in normal control group (group 4).

Statistics

The statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) software (ver. 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses. The threshold shifts and cell numbers across groups and subgroups were analyzed using one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) plus post hoc tests. A difference was considered statistically significant if p < .05. All data are presented as means ± SEM.

Results

Body Weight Changes

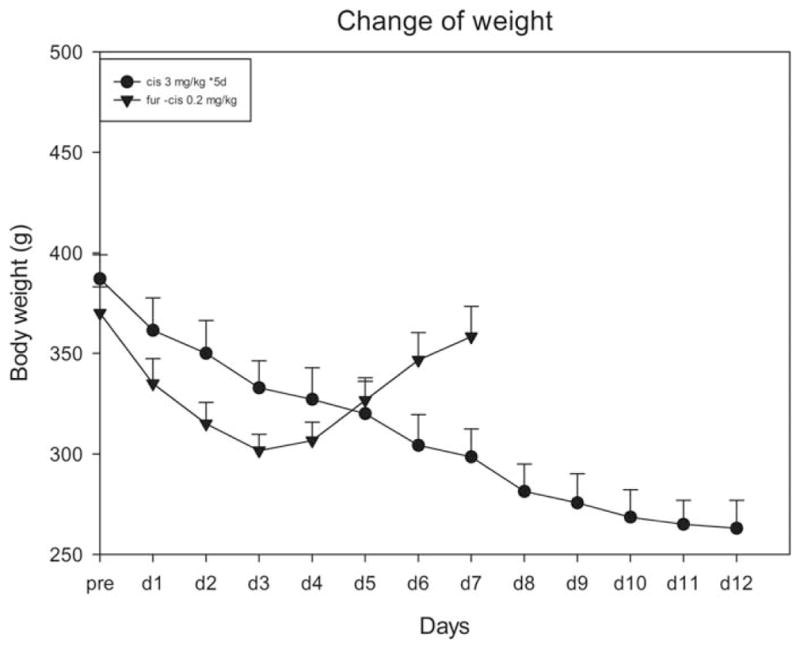

The animals’ body weight recovered in the coadministration group but decreased progressively during the experiment in the Cis-alone group (Figure 1). For example, at the end of the experiment, the body weight loss for the coadministration subgroup (furosemide 200 mg/kg, Cis 0.2 mg/kg, 30-min interval) was only 21.6 ± 6 g, while the corresponding value for cis-alone group was 118.6 ± 5.0 g (t0.05,11 = 13.0, p < .01).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the body weight changes caused by consecutive administration of Cis versus one injection of Cis in combination with furosemide.

Effects of a Single Furosemide Injection

Of the 15 guinea pigs that received single-injection furosemide, 12 survived, 6 of which were sacrificed at 0.5 and 1.5 hr (three at each time point) after the furosemide injection; the rest were sacrificed 12 hr after the injection when the threshold had recovered fully. Diuretic administration caused only a temporary ABR threshold shift, which was greatest between 0.5 and 1.5 hr after the injection. The threshold shift was flat across the frequencies tested. Thus, we calculated the frequency average of threshold shifts at various times after furosemide administration (Figure 2A). The largest shift, 53.3 ± 2.5 dB, was seen at 0.5 hr after the furosemide injection, the earliest time at which the ABR was recorded after furosemide. The shift decreased gradually thereafter and had disappeared 12 hr after the furosemide injection.

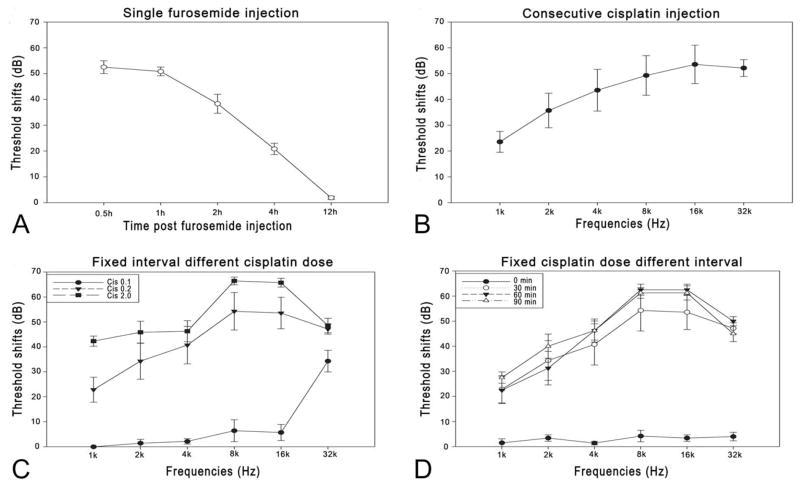

Figure 2.

ABR threshold shifts. (A) Shift of the frequency average after a single furosemide injection. The shift was largest (approximately 53 dB) 30 min after furosemide application (the earliest time tested) and recovered at 12 hr. (B) Threshold shift audiogram 7 days after consecutive cisplatin injections (3 mg/kg × 5 d). The shift was biased to high frequencies (up to 50 dB) and was lower at lower frequencies (around 30 dB). (C) Threshold shift audiogram 7 days after coadministration of 200 mg/kg furosemide and various Cis doses. Cis was administered 30 min after furosemide. (D) Threshold shift audiogram 7 days after coadministration of 0.2 mg/kg Cis and 200 mg/kg furosemide at various intervals. The threshold shift was nearly zero at a zero interval and higher at longer intervals.

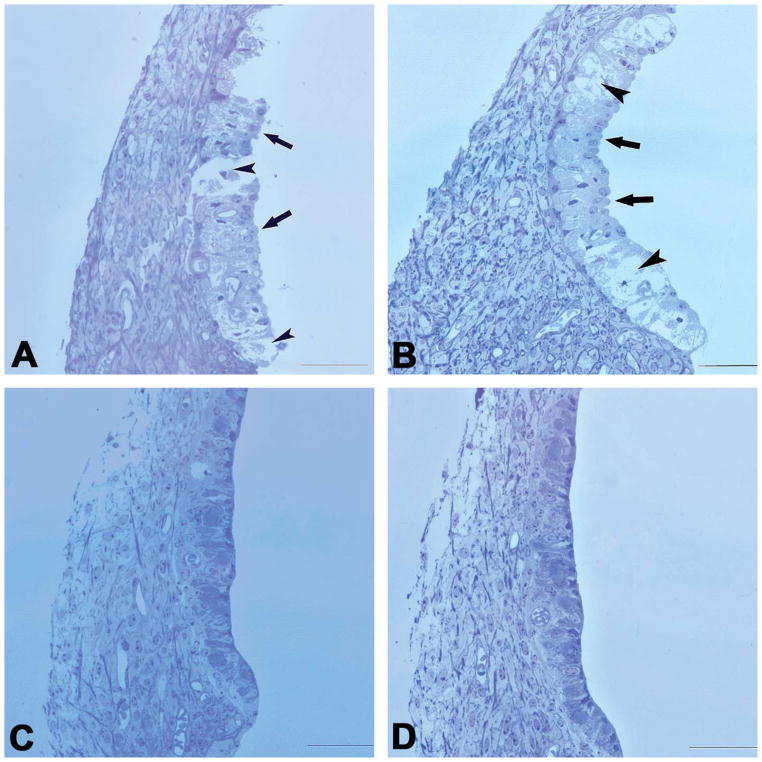

Morphological observation of the effects of furosemide focused on the lateral wall of the cochlea and was demonstrated through comparisons with 4 vehicle control guinea pigs (Figure 3). Changes in morphology were more evident in the SV of the basal turn. Compared with the normal control (Figure 3D), samples obtained 30 min after furosemide injection showed clearly swollen marginal cells (MCs) that bulged into the scala media, so that this surface of the SV became rough (Figure 3D, arrows). At this time point, many vacuoles were seen across the three cellular layers of SV into spiral ligament and the SV in the cross-section view was totally broken. The damage appeared to be reduced in samples acquired 90 min after furosemide administration (Figure 3B): the vacuoles were smaller and the swollen MCs decreased in number. Samples taken 12 hr after administration showed no obvious pathology compared with the control (Figure 3C), suggesting a full recovery of the structure after furosemide administration. No morphological abnormality was detected by optical microscopy in the basilar membrane or the organ of Corti from any animal in this group.

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional views of SV in the basal turn obtained at different times after a single furosemide injection. (A) At 30-min post-furosemide, severe SV edema and breakage were seen, which involved all three cellular layers in some places (short arrows), interrupting SV continuity. MCs were swollen and protruding into the scala media (long arrows), making the surface of the SV appear rough. (B) 90 min after furosemide administration, the SV breakage was not seen but swollen MCs and intermediate cells, large vacuoles across MC (short arrows) and the intermediate and probably basal cell layers remained. Moreover, many MCs still protruded into the SM (long arrows). (C) 12 hr after the furosemide injection, no obvious pathology was seen, compared with the control images. (D) Control. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Cochlear Lesions in the Cis-alone Group

In this group of 11 guinea pigs, Cis was given (i.m.) for 5 consecutive days at a dose of 3 mg/kg per day. Seven animals survived 7 days after the last injection (Table 1), resulting in a mortality rate of 36%. Figure 2B shows that the ABR threshold shifted from the baseline across frequencies 7 days after the last Cis injection. Significant threshold shifts were evident graphically and statistically in a one-way ANOVA on the frequency averaged threshold (F1,5 = 226.6, p < .01), with a frequency averaged shift of 43 ± 5 dB and the largest shift of 50 ± 7 dB at 16 kHz (Figure 2B).

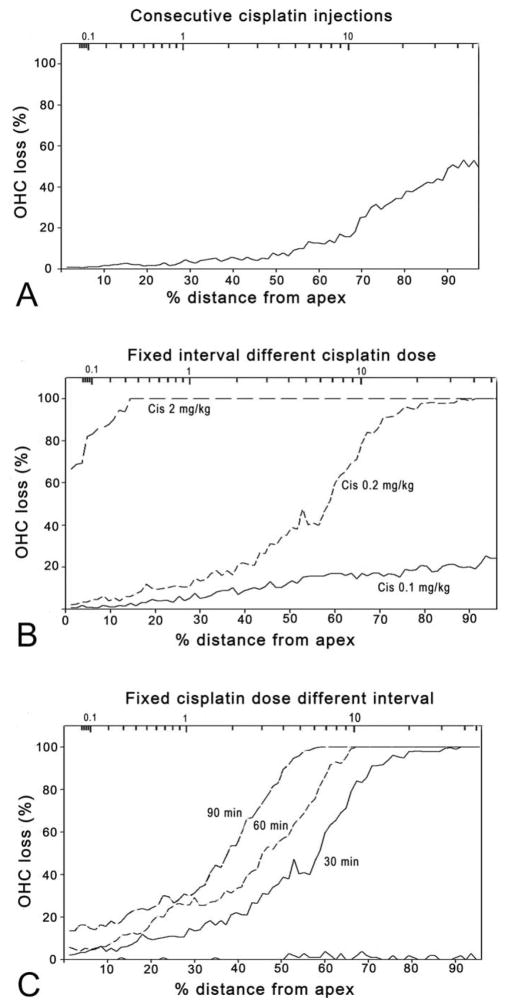

Hair cell loss corresponded roughly to functional deterioration. The overall out hair cell (OHC) loss was ~18% for the whole cochlea and followed the classic pattern: more in the basal turn and less in the apical turn (Figure 4A). No inner hair cell loss was apparent in this group.

Figure 4.

Cochleogram of out hair cell (OHC) loss. %OHC loss was measured as a function of distance from the apex to the base (lower horizontal axis) against the norm established using the control animals. The upper horizontal axis is the frequency of the region based upon the frequency–place map (Greenwood 1990). (A) Consecutive Cis injection group. OHC loss was more severe in the basal turn and milder in the apical turn. (B) Coadministration of Cis at various doses but a fixed interval (30 min) after furosemide. (C) Administration of fixed-dose Cis (0.2 mg/kg) at various intervals after furosemide.

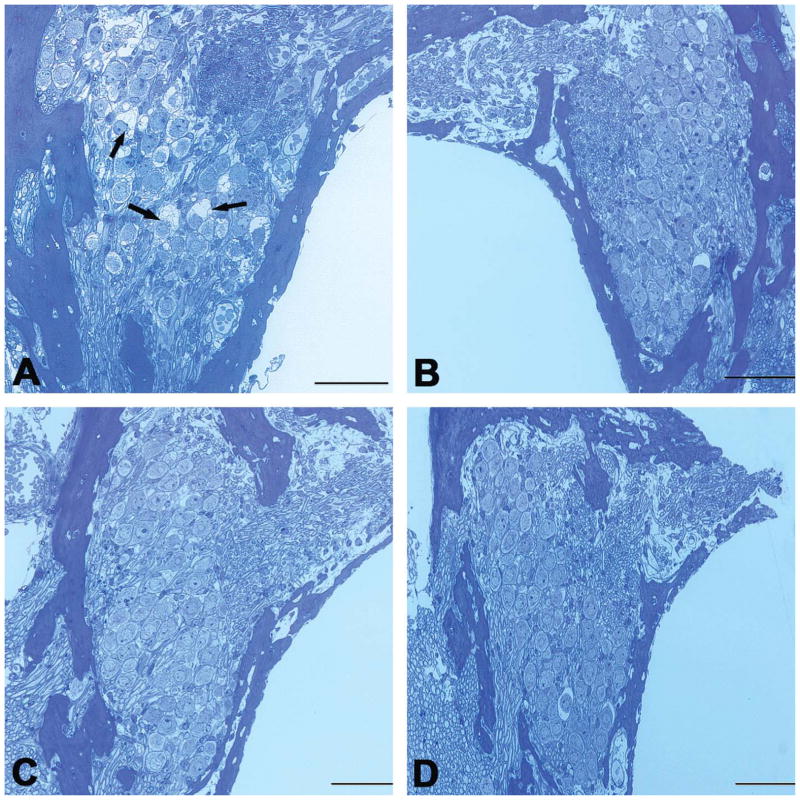

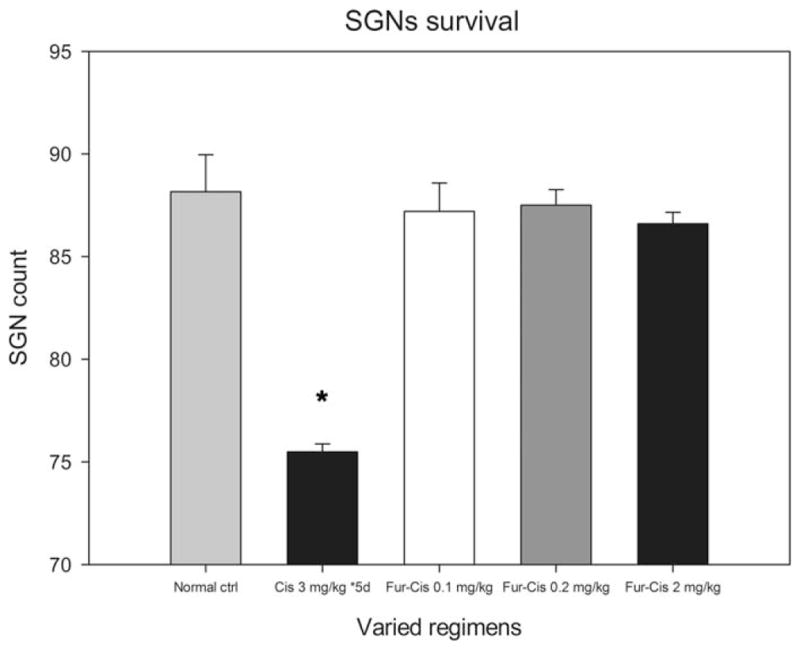

Consecutive Cis application also caused damage to SGNs. Figure 5 compares SGN lesions across all groups. As shown in Figure 5, the survived SGNs were counted under an optical microscope and compared against the normal control across all treatment groups. SGNs that showed clear lesions were not counted as survived (Figure 6A). Since there was obviously no difference across groups above basal turn, our statistical analysis was done only in basal turn. One-way ANOVA shows a clear effect of treatment (F4,25 = 6.1, p < .01). However, post hoc tests show that only in the Cis-alone group, the SGN count was significantly lower than that of control (Tukey’s test, p < .01). Myelin sheath detachment from the perikarya was also found in a few SGNs in the basal turn (Figure 6A) in this group. However, the number of lost SGNs appeared to be fewer than the number of OHC lost.

Figure 5.

SGN lesion at the basal turn. The SGN was calculated against the control values. A significant reduction in SGN was seen only in the basal turn in the group that received consecutive Cis injections (p < .05, as indicated by *).

Figure 6.

Representative cross-sectional views of SGNs. Consecutive Cis injection caused myelin sheath detachment in some SGNs; cell density did not decrease (A). Arrows show affected SGNs. No SGN damage was seen in any of the coadministration subgroups (B, C, D: Cis at 0.1, 0.2, and 2 mg/kg, respectively, observed 7 days after drug administration). Scale bar: 50 μm.

Cochlear Lesions in the Coadministration Group

Of the total 41 guinea pigs to which furosemide and Cis were coadministered, 34 survived for 7 days after the Cis injection, while mortality in this group was lower than that in the group that received consecutive Cis injections. For example, the mortality in the subgroup that received 0.2-mg/kg Cis 30 min after furosemide was only 14%, compared with 36% in the Cis-alone group. Six subgroups were classified according to the Cis doses and time intervals between the furosemide and Cis injections. Figure 2C shows the threshold shifts in animals 7 days post the drugs administration, which received different Cis doses with the time interval fixed at 30 min between furosemide and Cis. Cis administered at 0.1 mg/kg caused slight hearing loss only at very high frequencies in this subgroup (32 kHz, t0.05,5 = 8.215, p < .01), while 0.2-mg/kg Cis (30-min interval) caused much greater hearing loss across the whole frequency range with a frequency average of 46.3 + 2.5 dB, similar to that in the Cis-alone group (43.0 + 5.4 dB) in which a total dose of 15-mg/kg Cis was given (t0.05,11 = 0.512, p = .62), 75 times as high as that used in this Cis-fur subgroup. A further 10× increase in Cis dose did not lead to a proportional elevation in thresholds. The subgroup that received the highest Cis dose (2 mg/kg) had the largest threshold shifts (52.5 ± 4.4 dB in frequency average). A one-way ANOVA showed a significant effect of dose (F2,10 = 170.0, p < .01). Post hoc tests on total OHC loss count within the factor of dose showed that the OHC loss was significantly less in 0.1-mg/kg subgroup than in 0.2-mg/kg and 2-mg/kg subgroups, with the latter showing almost 100% loss (Tukey’s test, p < .01 for both 0.1 vs. 0.2 and 0.1 vs. 2 mg/kg; Table 1). In every subgroup, OHC loss was biased to the basal end (Figure 4B).

Figure 2D shows the effect of time interval between furosemide and Cis administration on ABR threshold shifts when the Cis dose was fixed at 0.2 mg/kg. Unexpectedly, simultaneous coadministration of the two drugs failed to cause any hearing loss (near zero threshold shifts). A two-way ANOVA was performed across the four subgroups of 0, 30-, 60-, and 90-min intervals against time interval and frequency factors. The effect of time interval was significant (F3,15 = 127.6, p < .01), though post hoc tests showed no significant difference between the 60-and 90-min interval subgroups in each frequency (p > .05); however, the shifts in these two subgroups appeared to be significantly larger than that of the 30-min interval subgroup (Tukey’s test, p < .05). In addition, the shift was significantly smaller in zero-delay subgroup than any other one (p < .01).

Hair cell loss (Figure 4C) was roughly consistent with the functional data. The total percentage OHC losses were 45.6 ± 2.4, 48.6 ± 3, and 56.2 ± 1% in the 30-, 60-, and 90-min interval subgroups, respectively. While a one-way ANOVA showed a significant overall effect of the interval, post hoc tests revealed no significant difference between 60-and both of the other subgroups (p > .05), but there were significant differences between the 90-min subgroup and 30-min subgroup (p < .05). The simultaneous coadministration of furosemide and Cis caused no evident hair cell loss (zero intervals).

While the combination of Cis and furosemide caused hearing loss and OHC lesions, no significant SGN lesion or loss or myelin sheath damage was seen in any subgroup (Figures 5, 6B–D), as evaluated 7 days after coadministration.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that by the recruitment of the method of coadministration of furosemide and Cis, the survival rate and physical conditions of subjects were boosted. Cis and furosemide coadministration was effective in establishing cochlear lesions. Using this regimen, 0.2-mg/kg Cis was found to cause more hearing loss and OHC loss than that produced by 3-mg/kg cis alone for 5 consecutive days. This reduction in Cis usage was largely responsible for the reduced mortality. Animals were healthier, as illustrated by the difference in body weight changes among the groups. More importantly, the two approaches impacted the SGNs differently: ~10% of the SGN in the basal turn was affected in the group receiving Cis alone, while no such lesion was seen in any of the coadministration subgroups, while the OHC loss was higher.

Mortality and Weight Changes

Use of the various regimens resulted in marked differences in mortality rates. The lower mortality rate, 17%, of coadministration represents a great advantage of this approach. This reduction in mortality is likely due to the lower dose of Cis used. Cis-induced mortality is known to be dose-dependent. In one study in guinea pigs, a single dose of Cis caused no evident gastrointestinal toxicity or nephrotoxicity and thus no body weight loss or mortality, unless the dose was >6 mg/kg (Ekborn et al. 2003). The dose of Cis used in our coadministration regimen was far lower than this critical point. Thus, the mortality observed in the coadministration subgroup was not likely caused by Cis; rather, it may be due to the impact of deep anesthesia.

Impact of Furosemide on the Blood–Labyrinth Barrier

The main effect of these diuretics on biochemistry is to depress the Na+-K+-2Cl− symporter (cotransporter) in the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, inhibiting sodium and chloride reabsorption. Because a similar Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter is expressed in cochlear MCs (Hibino et al. 2010), which are responsible for the generation and maintenance of endocochlear potential (EP), the application of these drugs decreases EP and thus cochlear transduction (Sakaguchi et al. 1998). However, depression of this transporter seems unlikely to be the reason for the cellular damage in SV. Previous research showed that SV damage appears to be initiated by ischemia observed shortly after diuretic administration (Liu, Zhou, and Yuan 1996). The lack of blood supply to the SV likely causes damage to various cells and the tight junctions among the cells. As the tight junctions bordering the SV and scala media exist among MCs and those bordering the SV and spiral ligament among the basal cells, damage to MCs and basal cells would be expected to create leakage of the drugs between the plasma and cochlear fluid (Ding, Jiang, and Salvi 2010). Although we did not intend to explore the time course of SV pathological changes in the present study, the observed changes in the morphology and function suggested increased permeability of SV to drugs for at least 90 min. This should provide a window of time for furosemide to facilitate Cis entry into the cochlea. The cells in the SV appear to have a notable self-repair ability, and leakage in this region is sealed within 12 hr after furosemide application.

Mechanism of the Cis and Furosemide Synergism in the Inner Ear

Enhancement of Cis-induced ototoxicity by diuretic coadministration has been reported previously (Bates, Beaumont, and Baylis 2002; Ding et al. 2007; Hirose and Sato 2011; Li et al. 2011). This synergistic effect has largely been attributed to two mechanisms. First, as described above, the SV damage by diuretics may increase cochlear drug quantities (Ding et al. 2002). Although the Cis concentration with the coadministration of furosemide has not been determined, EA has been demonstrated to significantly increase the concentration of gentamicin in perilymph if they are applied within an appropriate time frame (Ding et al. 2003). Second, temporary interruption of blood flow through the SV may result in localized ischemia–reperfusion injury, followed by a burst of oxygen radical species in the endolymph (Aubert et al. 1990). The increased oxidative stress may interact with the direct effect of Cis on apoptosis in the organ of Corti.

Timing is an important issue for the synergistic interaction between the two drugs. In the present study, we failed to find cochlear lesions in the subgroup in which Cis and furosemide were administered simultaneously.

However, the cochlear damage appeared to increase with increasing interval from 0 to 90-min between furosemide and cis. This change in the synergistic effect may be explained by the pharmacokinetics of the two drugs. Furosemide given as an intramuscular injection likely takes 30 min to damage the SV to an observable level. To our knowledge, however, there has been no systematic observation on the time line of SV damage by furosemide. If the Cis is largely eliminated from plasma before this time, no synergistic effect would be seen. The reported half-life of Cis injected i.v. can be divided into two phases: the fast phase has been reported as 20 to 30 min (Laurell et al. 1995) or less than 1 hr in other studies (Vermorken et al. 1984; Vermorken et al. 1986), while the half-life in the slow phase lasts several days (Vermorken et al. 1984; Vermorken et al. 1986). We assume that only the Cis in the fast phase would be responsible for the potential cochlear lesion in our case because in the coadministration with zero interval regimen, the Cis dose was low (0.2 mg/kg) and the residual drug in the plasma during the slow phase would likely not be sufficient to cause damage, even if it could freely enter the cochlea. Because the fast phase half-life is short, the Cis likely was largely eliminated when the SV damage peaked, and thus the amount of Cis that entered the cochlea would be insufficient to have any effect. This may be the case even if we take into consideration the fact that an intramuscular injection, not i.v., was used. On the other hand, the fact that Cis injection 60-min and 90-min post-furosemide caused a larger loss of OHC than that at 30-min post-furosemide may be due to the coincidence of increased SV permeability and Cis application, as well as the reperfusion that may have occurred 60 and 90 min after furosemide administration. One possibility is that SV permeability had partially recovered 60 and 90 min after furosemide administration; the increased blood flow at this time may bring more Cis to the SV and thus to the organ of Corti. Another possibility is that free radical levels continued to increase after the onset of ischemia and remained high for at least 40 to 80 min post-reperfusion (Ohlemiller and Dugan, 1999). OHC pathological changes, such as swelling and rupture, were found to be induced during this period, presumably via the increased stress of the hydroxyl radicals caused by ischemia–reperfusion (Tabuchi et al. 2002). Although the amount of Cis that enters the cochlea may be lower when it is applied 60- and 90-min post-furosemide injection versus if it was applied earlier, the synergistic interaction between Cis and free radicals may cause more hair cell loss. These ideas should be assessed in future studies.

Differences between Coadministration and Cis alone

While OHC death was comparable between the two approaches, the coadministration approach failed to create significant SGN lesions in the present study. To our knowledge, no report addresses the potential difference in SGN lesion induction between the two approaches. The mechanism of this difference is unclear, although we believe that it is likely due to the selective effect of furosemide on SV blood circulation. The lateral wall of the cochlea is supplied by radiating arterioles lateralis, while the modiolus and spiral lamina are supplied by radiating arterioles mediales and the cochlear artery. The blood flow in the vessels supplying the lateral wall of the cochlea diminished rapidly after injection of diuretics. In contrast, the radiating arterioles mediales to the modiolus and the spiral lamina in the cochlea retained a normal appearance at all times (Sergi et al. 2003; Ding et al. 2002; Ding et al. 2007). The mechanism(s) by which the diuretics selectively target lateral wall vessels is unknown. Probably, lateral wall vessels likely have an ultrastructure similar to that of the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle in the kidney, the basis of why loop diuretics target these two organs. As the dose of Cis was much lower in the coadministration regimens, the amount of Cis that entered the cochlea via other branches of the cochlear artery was also likely low if furosemide did not change the permeability of those vessels. Thus, the Cis leakage through the blood vessels to the SGNs was insufficient to cause SGN lesions.

Conclusions

In summary, in this study, we demonstrated the advantages of the coadministration of Cis and furosemide in establishing Cis ototoxicity in terms of a more rapid process and reduced mortality. However, the disadvantage of this approach is the lack of SGN lesions as seen in the Cis-alone regimen. Unless the purpose of a study is an OHC lesion, the coadministration model should be used with caution.

Acknowledgments

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (MOP79452), the State Key Development Program for Basic Research of China (Grant No. 2011CB504503), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30901669), the Sciences and Engineering Research Fund of Shanhai Jiaotong University of China (Grant No. 09XJ21004), and China National Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists (Grant No. 30925035).

Abbreviations

- ABR

auditory brain-stem response

- Cis

cisplatin

- EA

ethacrynic acid

- EP

endocochlear potential

- HC

hair cell

- MC

marginal cell

- OHC

out hair cell

- SGN

spiral ganglion neuron

- SV

stria vascularis

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

For reprints and permissions queries, please visit SAGE’s Web site at http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav.

References

- Alam SA, Ikeda K, Oshima T, Suzuki M, Kawase T, Kikuchi T, Takasaka T. Cisplatin-induced apoptotic cell death in Mongolian gerbil cochlea. Hear Res. 2000;141:28–38. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anniko M. Reversible and irreversible changes of the stria vascularis. An evaluation of the effects of ethacrynic acid separately and in combination with atoxyl. Acta Otolaryngol. 1978;85:349–59. doi: 10.3109/00016487809121463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubert A, Bernard C, Clauser P, Harpey C, Vaudry H. A cellular anti-ischemic agent, trimetazidine prevents the deleterious effects of oxygen free-radicals on the internal ear. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 1990;107:28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DE, Beaumont SJ, Baylis BW. Ototoxicity induced by gentamicin and furosemide. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:446–51. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KC, Rybak LP, Meech RP, Hughes L. D-methionine provides excellent protection from cisplatin ototoxicity in the rat. Hear Res. 1996;102:90–98. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Jiang H, Salvi RJ. Mechanisms of rapid sensory hair-cell death following co-administration of gentamicin and ethacrynic acid. Hear Res. 2010;259:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, Jiang H, Wang P, Salvi R. Cell death after co-administration of cisplatin and ethacrynic acid. Hear Res. 2007;226:129–39. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, McFadden SL, Browne RW, Salvi RJ. Late dosing with ethacrynic acid can reduce gentamicin concentration in perilymph and protect cochlear hair cells. Hear Res. 2003;185:90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding D, McFadden SL, Woo JM, Salvi RJ. Ethacrynic acid rapidly and selectively abolishes blood flow in vessels supplying the lateral wall of the cochlea. Hear Res. 2002;173:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekborn A, Lindberg A, Laurell G, Wallin I, Eksborg S, Ehrsson H. Ototoxicity, nephrotoxicity and pharmacokinetics of cisplatin and its monohydrated complex in the guinea pig. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:36–42. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0540-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton MA, Salvi RJ, Kamen BA, Saunders SS. Interaction of cisplatin and noise on the peripheral auditory system. Hear Res. 1990;50:211–23. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90046-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood DD. A cochlear frequency-position function for several species–29 years later. J Acoust Soc Am. 1990;87:2592–605. doi: 10.1121/1.399052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino H, Nin F, Tsuzuki C, Kurachi Y. How is the highly positive endocochlear potential formed? The specific architecture of the stria vascularis and the roles of the ion-transport apparatus. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:521–33. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0754-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Sato E. Comparative analysis of combination kanamycin-furosemide versus kanamycin alone in the mouse cochlea. Hear Res. 2011;272:108–16. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komune S, Snow JB., Jr Potentiating effects of cisplatin and ethacrynic acid in ototoxicity. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107:594–97. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1981.00790460006003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurell G, Andersson A, Engstrom B, Ehrsson H. Distribution of cisplatin in perilymph and cerebrospinal fluid after intravenous administration in the guinea pig. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;36:83–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00685738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Ding D, Jiang H, Fu Y, Salvi R. Co-administration of cisplatin and furosemide causes rapid and massive loss of cochlear hair cells in mice. Neurotox Res. 2011;20:307–19. doi: 10.1007/s12640-011-9244-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JX, Zhou XN, Yuan YG. Effects of furosemide on intra-cochlear oxygen tension in the guinea pig. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;253:367–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00178294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares V, Scherini E, Biggiogera M, Bernocchi G. Influence of cis-dichlorodiammineplatinum on the structure of the immature rat cerebellum. Exp Neurol. 1986;91:246–58. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(86)90065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden SL, Ding D, Jiang H, Salvi RJ. Time course of efferent fiber and spiral ganglion cell degeneration following complete hair cell loss in the chinchilla. Brain Res. 2004;997:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng LH, Kong BH, Zhang YZ, Yang XS, Wang LJ, Su SL, Jiang J, Cui BX, Wang B. Clinical study of topotecan and cisplatin as first line chemotherapy in epithelial ovarian cancer. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2007;42:683–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami SB, Sha SH, Schacht J. Antioxidant protection in a new animal model of cisplatin-induced ototoxicity. Hear Res. 2004;198:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlemiller KK, Dugan LL. Elevation of reactive oxygen species following ischemia-reperfusion in mouse cochlea observed in vivo. Audiol Neurootol. 1999;4:219–28. doi: 10.1159/000013845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirrier AL, Van den Ackerveken P, Kim TS, Vandenbosch R, Nguyen L, Lefebvre PP, Malgrange B. Ototoxic drugs: Difference in sensitivity between mice and guinea pigs. Toxicol Lett. 2010;193:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak LP. Ototoxicity of loop diuretics. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1993;26:829–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi N, Crouch JJ, Lytle C, Schulte BA. Na-K-Cl cotransporter expression in the developing and senescent gerbil cochlea. Hear Res. 1998;118:114–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry J, Kellie SJ. Severe neurotoxicity, ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity following high-dose cisplatin and amifostine. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;22:441–45. doi: 10.1080/08880010590964381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergi B, Ferraresi A, Troiani D, Paludetti G, Fetoni AR. Cisplatin ototoxicity in the guinea pig: Vestibular and cochlear damage. Hear Res. 2003;182:56–64. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss M, Towfighi J, Lord S, Lipton A, Harvey HA, Brown B. Cis-platinum ototoxicity: Clinical experience and temporal bone histopathology. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1554–59. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198312000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi K, Tsuji S, Fujihira K, Oikawa K, Hara A, Kusakari J. Outer hair cells functionally and structurally deteriorate during reperfusion. Hear Res. 2002;173:153–63. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teranishi M, Nakashima T, Wakabayashi T. Effects of alpha-tocopherol on cisplatin-induced ototoxicity in guinea pigs. Hear Res. 2001;151:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(00)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermorken JB, van der Vijgh WJ, Klein I, Gall HE, van Groeningen CJ, Hart GA, Pinedo HM. Pharmacokinetics of free and total platinum species after rapid and prolonged infusions of cisplatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986;39:136–44. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1986.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermorken JB, van der Vijgh WJ, Klein I, Hart AA, Gall HE, Pinedo HM. Pharmacokinetics of free and total platinum species after short-term infusion of cisplatin. Cancer Treat Rep. 1984;68:505–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Hoff DD, Schilsky R, Reichert CM, Reddick RL, Rozencweig M, Young RC, Muggia FM. Toxic effects of cis-dichlorodiam-mineplatinum(II) in man. Cancer Treat Rep. 1979;63:1527–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]