Abstract

We compared growth kinetics of Prorocentrum donghaiense cultures on different nitrogen (N) compounds including nitrate (NO3 −), ammonium (NH4 +), urea, glutamic acid (glu), dialanine (diala) and cyanate. P. donghaiense exhibited standard Monod-type growth kinetics over a range of N concentraions (0.5–500 μmol N L−1 for NO3 − and NH4 +, 0.5–50 μmol N L−1 for urea, 0.5–100 μmol N L−1 for glu and cyanate, and 0.5–200 μmol N L−1 for diala) for all of the N compounds tested. Cultures grown on glu and urea had the highest maximum growth rates (μm, 1.51±0.06 d−1 and 1.50±0.05 d−1, respectively). However, cultures grown on cyanate, NO3 −, and NH4 + had lower half saturation constants (Kμ, 0.28–0.51 μmol N L−1). N uptake kinetics were measured in NO3 −-deplete and -replete batch cultures of P. donghaiense. In NO3 −-deplete batch cultures, P. donghaiense exhibited Michaelis-Menten type uptake kinetics for NO3 −, NH4 +, urea and algal amino acids; uptake was saturated at or below 50 μmol N L−1. In NO3 −-replete batch cultures, NH4 +, urea, and algal amino acid uptake kinetics were similar to those measured in NO3 −-deplete batch cultures. Together, our results demonstrate that P. donghaiense can grow well on a variety of N sources, and exhibits similar uptake kinetics under both nutrient replete and deplete conditions. This may be an important factor facilitating their growth during bloom initiation and development in N-enriched estuaries where many algae compete for bioavailable N and the nutrient environment changes as a result of algal growth.

Introduction

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) have increased in coastal waters worldwide [1]–[4], exerting serious economic impacts on marine fisheries and aquaculture, and threatening public health and aquatic ecosystems [1], [5]. In Chinese coastal waters, HABs have increased in frequency, intensity, and duration in recent decades [6]–[8]. Prorocentrum donghaiense is a HAB species that frequently blooms during late spring and early summer in coastal waters around the East China Sea, including the Changjiang River Estuary, and coastal waters adjacent to Zhejiang in China [9]–[11], and coastal areas near Japan and South Korea [9]. Between 2000 and 2006, about 120 P. donghaiense bloom events (maximum cell densities of up to 3.6×108 cells·L−1) were reported from Chinese coastal waters (data from State Oceanic Administration, China) [2] and the spatial extent of these blooms ranged from several thousand to more than ten thousand km2. Blooms persisted several days to a month, during which time they caused serious economic impacts to marine fisheries, public health, and aquatic ecosystems [8], [10], [11]. Despite documentation regarding their impacts, the environmental factors promoting P. donghaiense bloom initiation and persistence are still unclear.

HABs are often linked to nutrient over-enrichment and consequent eutrophication of coastal waters including the East China Sea [5], [12]–[14]. The Changjiang River Estuary and East China Sea, where P. donghaiense blooms frequently occur, are hydrologically complex; they receive terrestrial nutrient inputs and freshwater through the watershed, but are also influenced by oceanic circulation that can affect particle transport in the estuary [15]. High nutrient loads to the watershed have been implicated as the proximate cause of P. donghaiense blooms in this system [16].

Dissolved inorganic N concentrations in the Changjiang River Estuary, mainly in the form of NO3 −, increased several-fold in the past few decades, reaching as high as 131.6 μmol N L−1 [15]–[18]. However, field studies have shown that NO3 − is rapidly consumed during the initiation of P. donghaiense blooms leading to NO3 −-depletion during blooms [16]. Our previous culture study determined that P. donghaiense can grow on multiple forms of N when they are supplied in saturating concentrations (50 μmol N L−1) [19]. However, it is not known whether P. donghaiense has a strong affinity for NO3 − or sources of recycled N (e.g., NH4 +, urea, and amino acids) when they are present at lower concentrations, more realistic of environmental concentrations once blooms are established.

The dissolved N pool in aquatic systems is dynamic, consisting of varying concentrations of dissolved inorganic N (DIN) and dissolved organic N (DON) compounds, many of which remain to be identified [20]–[22]. In Chinese coastal waters DIN (NO3 −+NO2 −+NH4 +) concentrations ranged 0–45.0 μmol N L−1 in the surface waters of Southern Yellow Sea during 2006–2007 [23] and 0–60.0 μmol N L−1 in waters adjacent to Hong Kong [24]. In the Changjiang River estuary and East China Sea, DIN (NO3 −, NO2 − and NH4 +) concentrations ranged 0–131.6 μmol N L−1 [15]–[18] over the same time period. In addition to DIN, urea can be an important component of the dissolved N pool and accounted for ∼10–60% of the total dissolved N in Hong Kong waters in summer of 2008 [24]. In the East China Sea, DON concentrations ranged 5.78–25.26 μmol N L−1, accounting for 44.0–88.5% of total dissolved nitrogen [16]. While concentrations of urea and DFAA were only a small component of the DON pool, 0.21–1.39 and 0.09–1.55 μmol N L−1, respectively, these compounds are labile and rapidly regenerated and turned over in the environment [21], [22].

To date, our understanding of the nitrogenous nutrition of P. donghaiense is limited. While previous research demonstrated that P. donghaiense can potentially utilize multiple inorganic and organic N compounds to grow [19], little is known about their affinity and capacity for growth on the diverse range of N compounds found in the environment. Therefore, we compared growth kinetics of P. donghaiense on medium supplied with NO3 −, NH4 +, urea, glu, dialanine (diala) or cyanate as the sole source of N. In addition, we used stable isotopes as tracers to compare uptake kinetics for these compounds in cultures acclimated under NO3 −-replete and -deplete culture conditions, conditions likely present in the environment during bloom initiation and maintenance phases, respectively.

Materials and Methods

2.1 Culture conditions

Prorocentrum donghaiense, was isolated from the East China Sea, and obtained from the Research Center of Hydrobiology, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China. Cultures were grown in artificial seawater enriched with, sterile, silicate-free f/2 trace metals and vitamins [25]. Concentrations of NO3 − were adjusted to conform to different experimental treatments (see below). Cultures were maintained in an environmental room at constant temperature (23±0.5°C) and irradiance (60±5 μmol quanta m−2 s−1) on a 12 h∶12 h (light: dark) light cycle and transferred to fresh medium every week to ensure cells remained in exponential growth phase for the duration of the experiments.

For all experiments, dissolved nutrients were measured after filtering through a 0.2 μm Supor filter. Samples were stored frozen until analysis. NO3 − and urea were measured on an Astoria Pacific autoanalyzer according to the manufacturer's specifications and using colorimetric methods [26]. NH4 + was determined using the manual phenol hypochlorite method [27]. Concentrations of dissolved free amino acids (DFAA) were measured by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [28]. Cells were enumerated using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Instruments). Samples were also collected onto GF/F filters and frozen for analysis of chlorophyll a (Chl a). Chl a concentrations were measured fluorometrically within one week of sample collection after extraction of cells in 90% acetone [29].

2.2 Experimental design

2.2.1 Growth kinetics experiments

Growth kinetics of P. donghaiense were determined for six different N compounds. Cultures were grown in triplicate, capped, 50 ml Pyrex test tubes containing 35 ml of culture suspended in f/2 modified medium amended with 0.5, 2, 5, 20, 50, 100, 200, or 500 μmol N L−1 supplied in the form of NO3 −, NH4 +, urea, glu, diala, or cyanate. Cultures were maintained in the environmental chamber under conditions described above for at least three generations prior to experiments in order to ensure cells were acclimated to treatment conditions. In vivo fluorescence was monitored to estimate chlorophyll biomass using a Turner Designs AU-10 fluorometer at the same time each day. Growth rates, μ (day−1), were calculated using a least squares fit to a straight line after logarithmic transformation of in vivo fluorescence data as described by Guillard [30] using the equation:

| (1) |

where N1 and N0 were the biomass (in vivo fluorescence) at time T1 and T0, respectively, during the linear portion of exponential phase growth.

The relationship between specific growth rate and N concentration was fitted to a Monod growth kinetic model using the equation:

| (2) |

where μ was the specific growth rate (day−1) calculated during the linear portion of exponential phase growth (Equation 1), μm was the maximum specific growth rate (day−1), S was the N concentration (μmol N L−1), and Kμ (half saturation constant; μmol N L−1) was the N concentration at μm/2 [31].

2.2.2 N uptake kinetic experiments

For N uptake kinetic experiments, cultures of P. donghaiense were grown on f/2 medium modified to contain 50 μmol N L−1 as NO3 − in two, 5-liter bottles. Cell abundance and ambient NO3 − concentrations were monitored daily. N-deplete uptake kinetic experiments were initiated after NO3 − concentrations were below the detection limit (0.05 μmol N L−1) for 5 consecutive days. Uptake kinetics experiments were initiated by dispensing 35 ml of NO3 −-deplete culture into 50 ml Pyrex test tubes and adding 15NO3 −, 15NH4 +, 15N-13C dually labeled urea, glu, or an algal amino acid mixture to duplicate test tubes at final substrate concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0 and 50.0 μmol N L−1. For NO3 −-replete uptake kinetic experiments, 35 ml of culture was dispensed into a series of 50 ml Pyrex test tubes and each was amended with an additional 50.0 μmol N L−1 as 14NO3 − to ensure the cultures were NO3 −-replete. As for NO3 −-replete treatments, 15NH4 +, and 15N-13C dually labeled urea, glu, or an algal amino acid mixture were added to duplicate tubes at the same concentrations indicated above, however, NO3 − uptake kinetics could not be measured in these NO3 −-replete cultures.

Uptake experiments were incubated at ∼23°C and at an irradiance of ∼60 μmol quanta m−2 s−1. After <1 hour, incubations were terminated by gentle filtration through precombusted (450°C for 2 hours) GF/F (nominal pore size ∼0.7 μm) filters. Filters were immediately frozen in sterile polypropylene cryovials until analysis. Frozen samples were dried in an oven at 40°C for 2 days and pelletized into tin discs prior to analysis on a Europa Scientific 20–20 isotope ratio mass spectrometer equipped with an automated N and C analyzer preparation unit. Specific uptake rates were calculated using a mixing model [32]:

|

(3) |

where the source pool was the dissolved N pool that was enriched during uptake experiments. Specific uptake rates (V; h−1) at each N concentration for each N substrate tested were fitted to a Michaelis-Menten model using the following equation:

| (4) |

where Vm is the maximum specific uptake rate (h−1); S the substrate concentration (μmol N L−1); and Ks the half saturation constant, the concentration (μmol N L−1) where V is equivalent to half of Vm, for the N substrate tested.

2.3 Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were carried out using Origin 7.0 and Microsoft Excel 2007 with the level of significance set at an α equal to 0.05. Differences between growth and uptake kinetic parameters were compared using a one-way ANOVA test. Monod and Michaelis-Menten curves were fitted using Origin 7.0.

Results

3.1 Growth kinetics of P. donghaiense

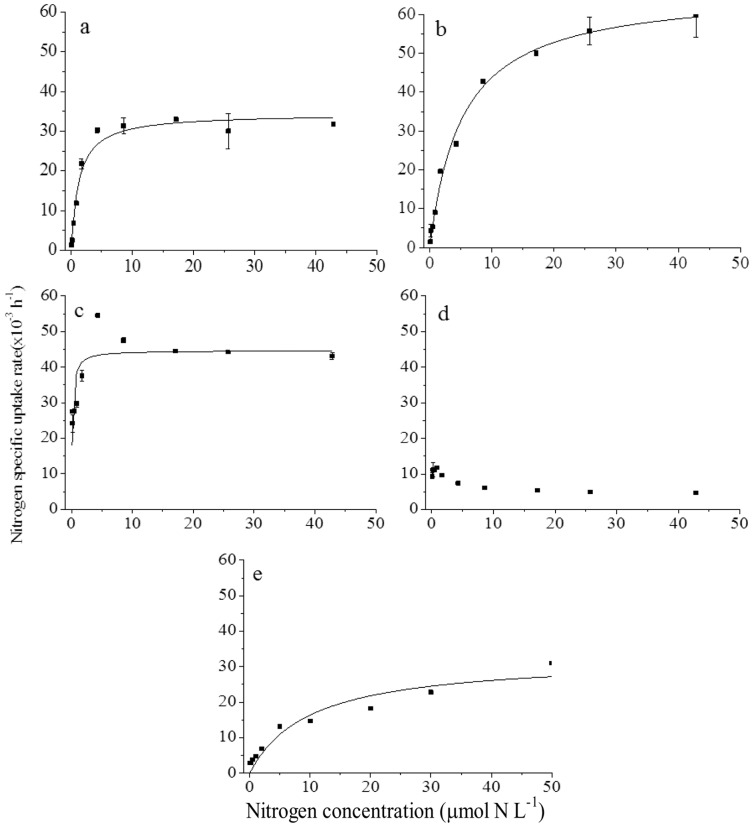

P. donghaiense exhibited standard Monod-type growth kinetics over N concentraions ranging from 0.5–500 μmol N L−1 for NO3 − and NH4 +, 0.5–50 μmol N L−1 for urea, 0.5–100 μmol N L−1 for glu and cyanate, and 0.5–200 μmol N L−1 for diala (Fig. 1). Maximum specific growth rates (μm) ranged from 0.71±0.04 to 1.51±0.06 d−1 (Table 1). The highest maximum growth rates were observed in cultures growing with glu or urea as the sole N source; maximum growth rates were a factor of 2 lower in cultures grown with NO3 −, NH4 +, cyanate, or diala supplied as the sole N source (Table 1). Half saturation constants (Kμ) ranged from 0.28±0.08 to 5.25±0.40 μmol N L−1. The lowest Kμ concentrations were observed in P. donghaiense cultures growing on media containing NO3 −, NH4 +, and cyanate as the sole source of N (0.28–0.51 μmol N L−1) (Table 1). In contrast, Kμ concentrations were an order of magnitude higher in cultures grown with urea, glu, or diala as the sole source of N suggesting higher affinities for cyanate, NO3 −, NH4 +, and urea than for glu and diala (Table 1).

Figure 1. Growth kinetics for P. donghaiense.

Growth rate as a function of NO3 − (a), NH4 + (b), urea (c), glu (d), cyanate (e) and diala (f) concentrations in batch cultures of P. donghaiense. Solid lines were fitted iteratively to the data according to the Monod equation and kinetic parameters were calculated as described in the text.

Table 1. Mean(±SD, n = 3) growth kinetic parameters for P. donghaiense growing with NO3 −, NH4 +, urea, glu, cyanate and diala as the sole source of N in the culture medium.

| Nitrogen species | μm (d−1) | Kμ (μmol N L−1) | Affinity (α) (μm/Kμ) | R2 |

| NO3 − | 0.74±0.02 | 0.42±0.02 | 1.74±0.13 | 0.82 |

| NH4 + | 0.83±0.02 | 0.51±0.03 | 1.65±0.10 | 0.92 |

| Urea | 1.50±0.05 | 2.05±0.04 | 0.73±0.02 | 0.91 |

| Glu | 1.51±0.06 | 5.25±0.40 | 0.29±0.01 | 0.98 |

| cyanate | 0.71±0.04 | 0.28±0.08 | 2.58±0.49 | 0.85 |

| Diala | 0.82±0.01 | 2.05±0.02 | 0.40±0.01 | 0.76 |

The maximum specific growth rate (μm), half saturation constant (Kμ) and affinity (α) for each nitrogen compound was calculated according to the Monod model.

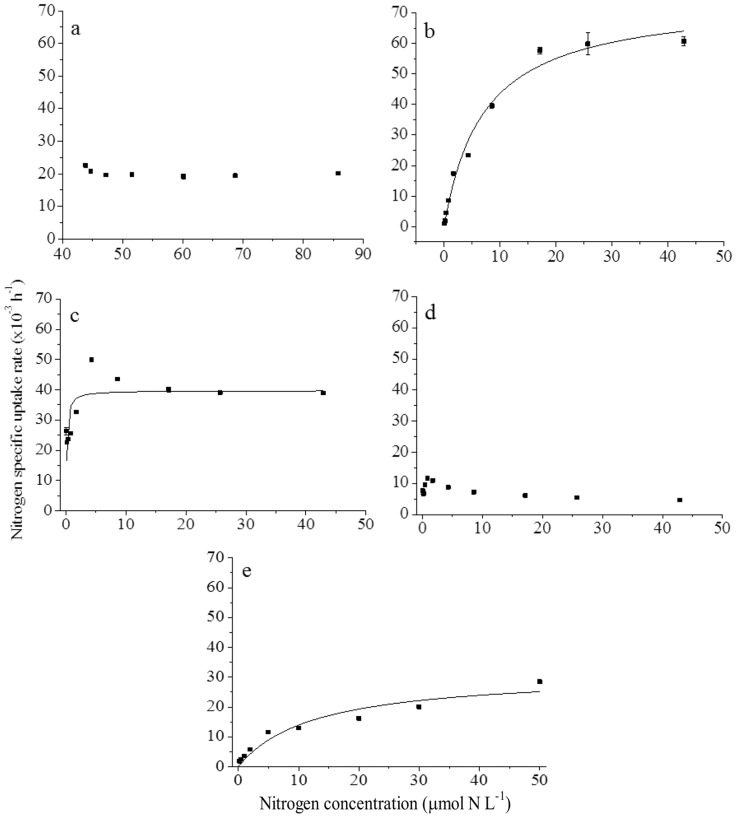

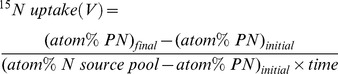

3.2 N uptake kinetics by P. donghaiense

Kinetics for NH4 +, urea, and algal amino acids conformed to Michaelis-Menten kinetics in both NO3-deplete and -replete cultures of P. donghaiense (Table 2; Figs. 2 and 3). While NO3 − uptake also conformed to Michaelis-Menten kinetics in NO3-deplete cultures (Fig. 2a), NO3 − uptake kinetics could not be measured in NO3 −-replete cultures because of the excess NO3 − in the growth media (Fig. 3a). Glu uptake did not conform to the Michaelis-Menten kinetic model in either NO3-deplete (Fig. 2d) or -replete (Fig. 3d) cultures of P. donghaiense and higher glu uptake rates were observed at lower glu concentrations.

Table 2. Mean (±SD, n = 2) uptake kinetic parameters (maximum specific uptake rate (Vm), half saturation constant (Ks) and affinity (α)) for P. donghaiense growing on NO3 − deplete culture media.

| Nitrogen species | Vm (×10−3 h−1) | Ks (μmol N L−1) | Affinity (α) (Vm/Ks) | R2 |

| NO3 − deplete cultures: | ||||

| NO3 − | 34.4±0.9 | 1.3±0.1 | 27.7±2.4 | 0.97 |

| NH4 + | 66.9±6.0 | 5.3±1.1 | 12.8±1.6 | 0.99 |

| Urea | 44.7±0.4 | 0.13±0.01 | 339.4±26.3 | 0.61 |

| algal amino acids | 32.6±1.0 | 9.9±0.9 | 3.3±0.2 | 0.93 |

| NO3 − replete cultures (50 μmol L−1 NO3 −): | ||||

| NH4 + | 74.7±3.4 | 7.1±0.4 | 10.5±0.1 | 0.99 |

| Urea | 39.7±0.2 | 0.12±0.01 | 332.9±26.7 | 0.49 |

| algal amino acids | 31.4±0.4 | 12.5±0.1 | 2.5±0.0 | 0.94 |

Figure 2. N uptake kinetics for P. donghaiense growing in NO3 −-deplete batch cultures.

Nitrogen uptake as a function of NO3 − (a), NH4 + (b), urea (c), glu (d), and algal amino acids (e) concentration in batch cultures of P. donghaiense growing on NO3 −-deplete media. Solid lines were fitted iteratively to the data according to the Michaelis-Menten equation and kinetic parameters were calculated as described in the text.

Figure 3. N uptake kinetics for P. donghaiense growing in NO3 −-replete batch cultures.

Nitrogen uptake rates as a function of NO3 − (a), NH4 + (b), urea (c), glu (d), and algal amino acid (e) concentrations in batch cultures of P. donghaiense growing on NO3 −-replete media. Solid lines were fitted iteratively to the data according to the Michaelis-Menten equation and kinetic parameters were calculated as described in the text.

Uptake kinetics for NO3 −, NH4 +, urea, and algal amino acids followed Michaelis-Menten type uptake kinetics in NO3 −-deplete batch cultures of P. donghaiense (Table 2; Fig. 2). Although results were sufficient to fit a Michaelis-Menten model for NH4 + uptake, NH4 + uptake by NO3 −-deplete P. donghaiense was not saturated even at the highest concentrations used in this experiment (Fig. 2b). Maximum specific uptake rates (Vm) of (66.9±6.0)×10−3 h−1 were calculated for NH4 + (Table 2), while Vm calculated for NO3 − ((34.4±0.9)×10−3 h−1), urea ((44.7±0.4)×10−3 h−1), and the algal amino acid mixture ((32.6±1.0)×10−3 h−1) were lower (Table 2). The half saturation constants (Ks) for uptake of NO3 −, NH4 +, urea, and algal amino acids by NO3 −-deplete P. donghaiense were 1.3±0.1, 5.3±1.1, 0.13±0.01 and 9.9±0.9 μmol N L−1, respectively (Table 2). The α values, which are often used as an index of nutrient affinity, were 27.7±2.4, 12.8±1.6, 339.4±26.3 and 3.3±0.2 for NO3 −, NH4 +, urea, and algal amino acids, respectively (Table 2) suggesting NO3 −-deplete P. donghaiense had the highest affinity for urea and the lowest for amino acids.

In NO3 −-replete cultures of P. donghaiense, maximum specific uptake rates (Vm) of NH4 + were greatest and not significantly different than those observed in NO3 −-deplete cultures (p>0.05; Table 2) (Table 2). Similarly, Vm for urea and algal amino acids were lower than those observed for NH4 + but comparable to those observed in NO3 −-deplete cultures (Table 2; Figs. 2 and 3). For urea, the Vm was significantly higher (p<0.05) but for algal amino acids there was no significant difference (p>0.05) between NO3 −-replete and NO3 −- deplete cultures of P. donghaiense (Table 2). Although there were significant differences between Ks values for NH4 + and algal amino acid uptake (p<0.05) between NO3 −-replete and -deplete cultures of P. donghaiense, the Ks values for NH4 +, urea, and the algal amino acid uptake in NO3 −-replete cultures of P. donghaiense were 7.1±0.4, 0.1±0.01 and 12.5±0.1 μmol N L−1 h−1, respectively (Table 2), similar to and showing the same pattern as values measured in NO3 −-deplete cultures. Similarly, the derived α values, a measure of nutrient affinity, were also similar for NO3 −-replete and -deplete cultures of P. donghaiense even though there were significant differences (p<0.05) in α between NO3 −-replete and -deplete cultures for algal amino acids (Table 2).

Discussion

Nutrient enrichment has been implicated as a causal factor in the occurrence of HAB events worldwide [5], [14], [33]. Both the form of dissolved N and its concentration in coastal and marine environments are thought to be important to the formation and development of HABs and phytoplankton blooms in general [13], [15], [34], [35]. However, different phytoplankton species and groups have different uptake capacities and affinities for specific inorganic and organic nitrogen compounds [19], [20], [36]. Many phytoplankton can also mobilize N from complex organic compounds such as peptides using extracellular enzymes thereby making N from these compounds available for uptake [32], [37]. In coastal areas, the concentration and composition of the dissolved N pool and the relative concentrations of various N compounds vary temporally and spatially, likely impacting the phytoplankton community composition and abundance on both short and longer timescales [15], [38], [39].

P. donghaiense is a mixotrophic species capable of both autotrophic and heterotrophic metabolisms. Previous research demonstrated that P. donghaiense can utilize inorganic and organic N compounds including urea, amino acids, small peptides, and cyanate [16], [19] as N sources. In addition, this organism can also ingest cyanobacteria, cryptophytes, and other dinoflagellates [40]. To better understand the N nutrition and capabilities of P. donghaiense, we conducted growth and N uptake kinetic experiments in cultured isolates to determine their affinity, preference, and capacity for growth on different N compounds and found that P. donghaiense had high maximum growth rates and exhibited high uptake capacities and affinities for a diverse suite of N compounds under both NO3 − -deplete and -replete conditions.

4.1 Growth kinetics

The Monod equation [41] has been used to describe saturation kinetics for nutrient-limited phytoplankton growth in many field and laboratory studies [42]–[44]. Maximum specific growth rates (μm) and half saturation constants (Kμ) are two important kinetic parameters derived from this model that quantify organismal growth responses to environmental nutrient concentrations. The initial slope of the Monod function (μm/Kμ) is thought to be a competitive index and used to assess the affinity of phytoplankton for particular nutrient substrates [45]. This model provides several useful tools for evaluating fitness of co-occurring phytoplankton with respect to the external nutrient availability in the environment [46]. Theoretical studies of resource competition suggest that the functional relationship between growth rate and the concentration of nutrient elements in the environment determines a species' ability to compete for that nutrient in the environment [46].

In our culture experiments, we found P. donghaiense grew well on DIN (NO3 − and NH4 +) and DON (urea, glu, diala and cyanate) compounds when they were supplied as the sole source of N (Fig. 1). P. donghaiense had comparable maximum specific growth rates when growing on NO3 −, NH4 +, cyanate, or diala (0.71–0.83 d−1); but maximum specific growth rates were a factor of 2 higher in cultures supplied with urea or glu as the sole source of N (1.50 and 1.51 d−1, respectively; Table 1). In contrast, half saturation constants for growth (Kμ) were more variable (0.28±0.08 to 5.25±0.40 μmol N L−1); Kμ values were lower (0.28–0.51 μmol N L−1) for cultures growing on NO3 −, NH4 +, or cyanate, and were an order of magnitude higher (2.05–5.25 μmol N L−1) in cultures grown on urea, glu, or diala (Table 1), suggesting a higher affinity for the inorganic N compounds. So, while P. donghaiense had higher maximum growth rates when supplied urea or glu as a sole source of N, cells had a higher affinity for cyanate, NO3 −, and NH4 + relative to urea, glu, and diala (Table 1) suggesting that the former compounds might be important sources N when nutrient concentrations are submicromolar.

Calculated growth kinetic parameters for P. donghaiense indicate that maximum specific growth rates and half saturation constants (Kμ) for NO3 −, NH4 +, and urea, were comparable to each other and those measured for other bloom-forming dinoflagellate species, Prorocentrum minimum, Cochlodinium polykrikoides and for Scrippsiella trochoidea growing on urea (Table 3). Maximum growth rates for P. donghaiense growing with NO3 −, NH4 +, urea or glu as the sole source of N were higher than those previously measured for P. minimum, C. polykrikoides, and S. trochoidea growing on the same N compounds (Table 3). S. trochoidea, P. minimum and C. polykrikoides had comparable maximum specific growth rates when going on urea (0.44–0.47 d−1; Table 3), but these were all lower than the maximum specific growth rate observed for P. donghaiense in this study(1.50 d−1) (Table 1). While P. donghaiense (this study) and C. polykrikoides [44] exhibited comparable maximum specific growth rates on NO3 −, NH4 +, urea and glu, P. minimum exhibited higher specific growth rates in cultures growing on urea or NO3 − (0.45 and 0.43±0.01 d−1, respectively) relative to cultures growing on NH4 + or glu (0.27±0.05 and 0.23±0.02 d−1, respectively) [43].

Table 3. Summary of mean (±SD) maximum specific growth rates (μmax, d−1) and half saturation constants (kμ, μmol N L−1) for nitrate (NO3 −), ammonium (NH4 +), urea, and glutamic acid (glu) estimated for different dinoflagellate species.

| Species | NO3 − | NH4 + | Urea | glu | Reference | ||||

| μmax | kμ | μmax | kμ | μmax | kμ | μmax | kμ | ||

| Prorocentrum minimum | 0.43±0.01 | 1.10±0.40 | 0.23±0.02 | 0.70±0.40 | 0.45 | <0.50 | 0.27±0.05 | 53.0±31.0 | [43] |

| Cochlodinium polykrikoides | 0.43±0.01 | 2.06±0.32 | 0.44±0.02 | 2.69±0.49 | 0.44±0.01 | 2.90±0.46 | 0.53±0.02 | 1.91±0.47 | [44] |

| Scrippsiella trochoidea | - | - | - | - | 0.47 | 21.83 | - | - | [47] |

| P. donghaiense | 0.74±0.02 | 0.42±0.02 | 0.83±0.02 | 0.51±0.03 | 1.50±0.05 | 2.05±0.04 | 1.51±0.06 | 5.25±0.40 | This study |

But unlike P. donghaiense, P. minimum had the lowest half saturation constants for growth on urea, followed by NO3 − and NH4 +; both had the highest half saturation constants for glu (Table 3) [43]. In contrast, C. polykrikoides had higher half saturation constants for urea and NH4 + than for NO3 − and glu [44]. The half saturation constant for S. trochoidea growing on urea was much higher than for the other three dinoflagellates suggesting a low affinity for growth on this compound [47].

In this study, P. donghaiense also exhibited maximum growth rates and half saturation constants comparable to those for growth on NH4 + and NO3 −, when growing with cyanate and dialanine as the sole source of N (Fig. 1; Table 1). Because peptides and cyanate are degradation products of decaying cells [32], [48], these compounds were likely available to P. donghaiense during bloom maintenance when NO3 − concentrations are exhausted and recycling processes are important for maintaining cell biomass and turnover. The concentration and turnover of these organic compounds have not been assessed in natural systems where blooms of P. donghaiense occur. Comparisons of P. donghaiense growth kinetics with those of co-occurring species relative to the bioavailable DIN and DON compounds in the environment is warranted to elucidate how competitive interactions among phytoplankton populations contributes to bloom initiation and maintenance.

4.2 Uptake kinetics

The Michaelis-Menten equation is often used to describe the relationship between external nutrient concentrations and their uptake rates [49]–[51]. As for growth kinetics, kinetic parameters for N uptake have been used to assess the relative preference (and affinity) for different N substrates in the environment [50], [52]. While kinetic parameters are usually measured in nutrient-deplete cultures, we conducted N uptake kinetic experiments in both NO3 −-deplete and -replete batch cultures of P. donghaiense because NO3 − concentrations are generally high in the Changjiang River estuary when blooms of this organism initiate [15]–[18] but then become rapidly depleted as algal biomass increases. Here we compared N uptake kinetics for NO3 − (N-deplete cultures only), NH4 +, urea, and algal amino acids in N-replete and –deplete cultures of P. donghaiense (Table 2; Figs. 2, 3).

Michaelis-Menten type uptake kinetics were observed for all N compounds tested except glu (Figs. 2d, 3d). For NH4 +, the uptake capacity (Vm) for exponentially growing P. donghaiense was ∼1.5, 1.9, and 2.1 times greater than those for urea, NO3 −, and the algal amino acids, respectively, in both NO3 −-deplete and -replete cultures. The half saturation constants, which are also used to estimate nutrient affinity under nutrient-limiting conditions, suggest similar nutrient preferences under NO3 −-deplete and –replete conditions; urea >>>NO3 −>NH4 +> algal amino acids for NO3 −-deplete P. donghaiense, and urea >>>NH4 +> algal amino acids for NO3 −-replete P. donghaiense (Table 2; Figs. 2, 3).

Differences in kinetic parameters are often observed in cells growing under N-replete versus -deplete conditions [53]. Many N-starved cells are capable of enhanced N uptake when nutrients are resupplied, and N-replete cells can have higher half-saturation constants than those grown under N-depleted conditions [36]. While our kinetics parameters conformed to this norm based on our statistical analyses, it was surprising that uptake kinetics for NH4 +, urea, and amino acids were similar in nutrient-replete and -deplete cultures of P. donghaiense (Table 2; Figs. 2&3). Ambient NO3 − concentrations were ∼43 μmol N L−1 when we initiated our uptake experiments in the N-replete cultures and this should have been saturating for NO3 − uptake (Table 2). However, kinetic parameters in NO3 −-replete and -deplete batch cultures were similar suggesting that even when NO3 − concentrations are high, such as during bloom initiation, P. donghaiense has a high affinity for other N compounds that may available in the environment and this may give them a competitive edge over other phytoplankton.

NO3 − and NH4 + are the dominant DIN species thought to fuel the bulk of primary production in estuarine, coastal, and oceanic environments. In Chinese estuaries and coastal waters where P. donghaiense blooms, NO3 − and NH4 + concentrations are commonly 0–20.0 and 0–3.0 μmol N L−1, respectively [16]. In this study, we found P. donghaiense had higher maximum uptake rates for NH4 + than NO3 −, urea and amino acids in both NO3 −-deplete and -replete batch cultures (Table 2; Fig. 2). However, because of the low half saturation constants for urea uptake (0.13 and 0.12, respectively), both N-deplete and -replete cultures of P. donghaiense had a much higher affinity for urea than for inorganic N or amino acids. This is consistent with results from a field study in the East China Sea during a P. donghaiense dominant bloom [11], [16]. As we know, DON can constitute more than 80% of the TDN in surface waters in coastal systems and the open ocean [21] where it can also contribute to primary productivity [20]. In the East China Sea, DON accounted for 44.0%–88.5% of the TDN, and urea and DFAA accounted for 1.7%–36.3% of the DON, before and during a P. donghaiense bloom [16]. In our experiments, P. donghaiense had similar maximum specific uptake rates for urea and amino acids under NO3 − -deplete and -replete conditions (Table 2) and half saturation constants for urea uptake were much lower than for NO3 −, NH4 + and amino acids, suggesting a higher affinity for urea than for other N compounds tested. Further, during a bloom dominated by P. donghaiense in the East China Sea in 2005, maximum specific uptake rates for urea were 11–28×10−3 h−1 and half saturation constants were 0.25–14.95 μmol N L−1, which are comparable to results presented here for culture studies [16]. These results suggest that even if present at low concentrations, urea has the potential to be an important source of N fueling the growth of P. donghaiense and this may be important for out-competing co-occurring phytoplankton during bloom initiation and/or supporting the persistence of bloom organisms in the environment once NO3 − has become depleted.

A wide range of maximum uptake rates and half saturation constants for NO3 −, NH4 +, urea, and amino acid uptake have been observed among dinoflagellates both in laboratory cultures and experiments using natural populations during blooms (Table 4). Higher maximum uptake rates have been observed for NH4 + compared to NO3 −, urea or amino acids for most species including: cultures of P. minimum, Heterosigma akashiwo and Alexandrium minutum, and assemblages dominated by Dinophysis acuminate (representing ∼91% of the phytoplankton biomass), P. minimum (representing >93% of the total phytoplankton cells), Alexandrium catenella (more than 99% of the phytoplankton) and Karenia mikimotoi (cell density up to 8×10−6 cell·L−1) (Table 4). In contrast, in cultures of the diatom Pseudonitzschia australis, maximum NO3 − uptake rates exceeded NH4 + uptake rates in populations growing on NO3 −-deplete condition [54]. The high variability in maximum uptake rates and half saturation constants between species and experiments could be due to differences in the preconditioning of cells prior to kinetic studies. Nutritional history was a significant factor affecting N uptake rates by P. minimum culture [55]. N uptake kinetics are known to vary with in response to the physiological status and their nutrient history of cells [36]. Our culture experiments demonstrated that P. donghaiense can take up NH4 + and other N compounds at high rates even when ambient NO3 − concentrations are high (e.g., ∼43 μmol N L−1). This nutritional flexibility may contribute to the initiation and long duration of P. donghaiense blooms in nature. While blooms initiate when NO3 − concentrations are high, NO3 − is rapidly depleted as blooms progress.

Table 4. Summary of mean (±SD) maximum uptake rates (Vmax, ×10−3 h−1) and half saturation constants (ks, μmol N L−1) for ammonium (NH4 +), nitrate (NO3 −), urea and amino acid (glutamic acid (glu), glutamate (gln), glycine (gly) or amino acid mixture) uptake by HAB dinoflagellate species.

| Species | Experiment type | NO3 − | NH4 + | urea | amino acids | Reference | ||||

| Vmax | ks | Vmax | ks | Vmax | ks | Vmax | ks | |||

| Heterosigma akashiwo | Culture | 18.0±1.08 | 1.47±0.25 | 28.0±2.17 | 1.44±0.35 | 2.89±0.24 | 0.42±0.16 | - | - | [52] |

| Prymnesium parvum | Culture | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10.5–13.1 | 0.09–0.10 | [62] b |

| Prorocentrum minimum | Culture | - | - | 46–65 | 1.2–4.6 | 3E-01–8E-01 | 0.05–5.4 | 4–7 | 0.48–3.54 | [63] c |

| Prorocentrum minimum | Culture | 95.8±5.5–341.2±90.7 | 0.68±0.23–23.3.0±11.1 | 1070±120.5–±88.7 | 2.48±0.8–6.23±0.47 | 149.2±12.3–480.5±13.4 | 0.86±0.16–1.82±0.59 | 271.6±35.6 517.1±125.8 | 14.1±6.8–22.6±9.9 | [55] a, d |

| Prorocentrum minimum (Choptank River) | Field | 18.4±4.3–53.8±5.7 | 1.4±0.2–7.1±5.5 | 327±172.5–868.6±159 | 2.4±0.3–9.8±2.6 | 38.2±16.9–492.6±71.5 | 6.6±4.0–17.9±5.1 | 84.2±12.9–1516±134 | 4.8±2.3–26.6±4.1 | [55] a, d |

| Prorocentrum donghaiense | Culture (NO3 − deplete) | 34.4±0.9 | 1.3±0.1 | 66.9±6.0 | 5.3±1.1 | 44.7±0.4 | 0.13±0.01 | 32.6±1.0 | 9.9±0.9 | This study a |

| Prorocentrum donghaiense | Culture (NO3 − replete) | - | - | 74.7±3.4 | 7.1±0.4 | 39.7±0.2 | 0.12±0.01 | 31.4±0.4 | 12.5±0.1 | This study a |

| Prorocentrum donghaiense dominant | Field | - | - | 700 | 3.9 | 17.0 | 5.3 | 25 | 1.8 | [16] c |

| Karenia mikimotoi | Field | 18.0 | 43.6 | 500 | 4.9 | 20.0 | 1.4 | 11 | 1.7 | [16] c |

| Alexandrium minutum | Culture | 0.29±0.01–0.70 | 0.22±0.02–0.28±0.06 | 0.65±0.01–1.49 | 0.25±0.04–0.38±0.04 | - | - | - | - | [58] e |

| Alexandrium catenella | Culture | 3–47 | 0.6–28.1 | 26.0±2.0 | 2.0±0.6 | 25±8 | 28.4±15.0 | - | - | [66] |

| Alexandrium catenella | Field | - | - | 14.9±0.8 | 2.52±0.36 | 3.5±0.2 | 0.65±0.12 | - | - | [39] |

| Alexandrium catenella | Field | 24±2 | 4.6±1.1 | 64±5 | 8.4±1.7 | 61±8 | 43.9±8.8 | - | - | [66] |

| Dinophysis acuminata | Field | 3.5±0.2 | 0.79±0.26 | 13.9±0.2 | 0.67±0.06 | 6.2±0.6 | 0.53±0.22 | - | - | [39] |

| Lingulodinium polyedrum | Field | 22.4 | 0.47 | 47.1 | 0.59 | 61.6 | 0.99 | - | - | [65] |

| Cochlodinium spp. | Field | 0.9±0.0 | 1.0±0.4 | - | - | 1.9±0.1–2.2±0.3 | 1.6±0.2–6.6±2.0 | - | - | [67] |

| Mixed dinoflagellate assemblages (Neuse Estuary) | Field | 4.0±1.6 | 0.5±0.1 | 52.9±1.7 | 4.9±0.5 | 5.8±0.5 | 0.4±0.1 | 2.3±0.5 | 2.3±1.7 | [55] a, d |

The a, b and c indicate that an algal amino acid mixture, glutamic acid (glu) or glycine (gly) used as N substrates, respectively. The d and e f indicate the units are fmol N cell−1 h−1 and pmol N cell−1 h−1, respectively.

Studies have shown that nutrient preconditioning and physiological status [36], cell size [56], [57], growth rates [50], [55], [58], incubation time (minutes versus hours) [51], N substrate interactions [58]–[61], N preconditioning [53], [62], the DIN/DIP ratio [63], and environmental factors such as irradiance and temperature [59], [64], [65] can all contribute to variations in nutrient uptake kinetics. Because we conducted short incubations of uniform duration in culture systems acclimated to identical conditions, it is unlikely that these factors contributed to variability in uptake rates observed in this study.

While there are still few studies examining N uptake during blooms of P. donghaiense, kinetic parameters for NO3 −, NH4 +, urea, and glycine uptake were compared during successive dinoflagellate blooms in Changjiang River estuary and East China Sea coastal waters in 2005 [16]. In these mixed blooms, Karenia mikimotoi was the dominant species initially and then was succeeded by P. donghaiense. In most cases, when the bloom was dominated by P. donghaiense, the Ks values for urea and glycine uptake (Ks, 5.3 and 1.8 μmol N L−1 respectively) were higher than when the bloom was dominated by K. mikimotoi (Ks, 1.4 and 1.7 μmol N L−1 respectively) (Table. 4). The differences in the Ks of the two bloom species for NO3 − and NH4 + may have been a driver of species succession as concentrations of these compounds were drawn down during the K. mikimotoi bloom which preceded the P. donghaiense bloom.

Cell-normalized N uptake rates by P. donghaiense-dominated assemblages in the Chanjiang River estuary were comparable to cell-normalized N uptake rates measured in the culture studies reported here. Uptake rates of NH4 +, urea, and glycine were ∼96, ∼22 and ∼38 fmol N cell−1 h−1, respectively, during blooms of P. donghaiense (cell density and Chl a were ∼5.0×106 cells L−1 and 8.66–9.68 μg L−1, respectively) [11], [16] while maximum uptake rates for NH4 +, urea and algal amino acids observed in this study were ∼119, 78 and ∼53 fmol N cell−1 h−1, respectively. This suggests that uptake may not have been saturated in the environment. The Ks values of NO3 − and urea for P. donghaiense were much lower than the environmental concentrations, but except for NH4 + and DFAA, which suggest that P. donghaiense have higher affinities on NO3 − and urea than those for NH4 + and DFAA, but the later two also contribute on P. donghaiense bloom initiation and duration.

Summary

Results presented here demonstrate that P. donghaiense can grow on a diverse array of N compounds as their sole source of N, including inorganic N (NO3 − and NH4 +) and organic N compounds such as urea, dissolved free amino acids, small peptides, and even cyanate to support their growth. Maximum specific growth rates varied by a factor of 2 for all of the N compounds tested. In addition, uptake kinetics for regenerated N sources (e.g., NH4 +, urea, and amino acids) were similar under NO3 −-replete and -deplete conditions suggesting that competition for these compounds may contribute to the success of P. donghaiense during bloom initiation when NO3 − concentrations are high, and maintenance, when NO3 − concentrations have been depleted. The nutritional flexibility exhibited by P. donghaiense likely contributes to its success in eutrophic environments where inorganic nutrient concentrations can be high, but where nutrient concentrations and the dominant form of bioavailable N rapidly change in response to stochastic events and the formation of algal blooms.

Acknowledgments

We are pleased to acknowledge Peter W. Bernhardt for contributing isotopic analysis and Drs. Katherine C. Filippino and Yingzhong Tang for their kind assistance in reviewing earlier versions of this manuscript.

Funding Statement

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the China Scholarship Council to Zhangxi Hu. In addition, this work was supported by NOAA and NSF grants to MRM, and Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant Numbers 40776078, 40876074, 41176104). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Anderson DM (1997) Turning back the harmful red tide. Nature 388: 513–514. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang J, Wu J (2009) Occurrence and potential risks of harmful algal blooms in the East China Sea. Science of the Total Environment 407: 4012–4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson DM, Cembella AD, Hallegraeff GM (2012) Progress in understanding harmful algal blooms: paradigm shifts and new technologies for research, monitoring, and management. Annual Review of Marine Science 4: 143–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glibert PM, Burkholder JM, Kana TM (2012) Recent insights about relationships between nutrient availability, forms, and stoichiometry, and the distribution, ecophysiology, and food web effects of pelagic and benthic Prorocentrum species. Harmful Algae 14: 231–259. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heisler J, Glibert PM, Burkholder JM, Anderson DM, Cochlan WP, et al. (2008) Eutrophication and harmful algal blooms: A scientific consensus. Harmful Algae 8: 3–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan T, Zhou M, Zou J (2002) A national report of HABs in China. In: “Max” Taylor FJR, Trainer VL, editors. PICES Scientific Report No. 23, Harmful algal blooms in the PICES region of the North Pacific. pp. 21–33.

- 7. Lu S, Hodgkiss IJ (2004) Harmful algal bloom causative collected from Hong Kong waters. Hydrobiologia 512(1–3): 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou M (2010) Environmental Settings and Harmful Algal Blooms in the Sea Area Adjacent to the Changjiang River Estuary. Coastal Environmental and Ecosystem Issues of the East China Sea, pp. 133–149 (Citable URI: http://hdl.handle.net/10069/23506).

- 9. Lu D, Goebel J (2001) Five red tide species in genus Prorocentrum including the description of Prorocentrum donghaiense Lu Sp. Nov. from the East China Sea. Chinese Journal of Oceanography and Limnology 19(4): 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lu D, Goebel J, Qi Y, Zou J, Han X, et al. (2005) Morphological and genetic study of Prorocentrum donghaiense Lu from the East China Sea, and comparison with some related Prorocentrum species. Harmful Algae 4(3): 493–505. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li J, Glibert PM, Zhou M, Lu S, Lu D (2009) Relationships between nitrogen and phosphorus forms and ratios and the development of dinoflagellate blooms in the East China Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series 383: 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paerl HW (1997) Coastal eutrophication and harmful algal blooms: importance of anthropogenic deposition and groundwater as ‘new’ nitrogen and other nitrogen sources. Limnology and Oceanography 42: 1154–1165. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anderson DM, Glibert PM, Burkholder JM (2002) Harmful algal blooms and eutrophication: nutrient sources, composition, and consequences. Estuaries 25: 704–726. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glibert PM, Burkholder JM (2006) The complex relationships between increasing fertilization of the earth, coastal eutrophication and proliferation of harmful algal blooms. In: Granéli E, Turner J, editors. Ecology of harmful algae. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. pp. 341–354.

- 15. Zhou M, Shen Z, Yu R (2008) Responses of a coastal phytoplankton community to increased nutrient input from the Changjiang (Yangtze) River. Continental Shelf Research 28: 1483–1489. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li J, Glibert PM, Zhou M (2010) Temporal and spatial variability in nitrogen uptake kinetics during harmful dinoflagellate blooms in the East China Sea. Harmful Algae 9: 531–539. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shen Z, Liu Q, Zhang S, Miao H, Zhang P (2003) A nitrogen budget of the Changjiang River catchment. Ambio 32(1): 65–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chai C, Yu Z, Song X, Cao X (2006) The status and characteristics of eutrophication in the Yangtze River (Changjiang) Estuary and the adjacent East China Sea, China. Hydrobiologia 563: 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu Z, Mulholland MR, Duan S, Xu N (2012) Effects of nitrogen supply and its composition on the growth of Prorocentrum donghaiense . Harmful Algae 13: 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Antia NJ, Harrison PJ, Oliveira L (1991) Phycological reviews: the role of dissolved organic nitrogen in phytoplankton nutrition, cell biology, and ecology. Phycologia 30: 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Berman T, Bronk DA (2003) Dissolved organic nitrogen: a dynamic participant in aquatic ecosystems. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 31: 273–305. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bronk DA, Steinberg D (2008) Nitrogen regeneration. In: Capone DG, Bronk DA, Mulholland MR, Carpenter EJ, editors. Nitrogen in the marine environment. Academic Press. pp. 385–468.

- 23. Fu M, Wang Z, Li Y, Li R, Sun P, et al. (2009) Phytoplankton biomass size structure and its regulation in the Southern Yellow Sea (China): seasonal variability. Continental Shelf Research 29: 2178–2194. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yuan X, Glibert PM, Xu J, Liu H, Chen M, et al. (2012) Inorganic and organic nitrogen uptake by phytoplankton and bacteria in Hong Kong waters. Estuaries and Coasts 35: 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guillard RRL (1975) Culture of phytoplankton for feeding marine invertebrates. In: Smith WL, Chanley MH, editors. Culture of Marine Invertebrate Animals. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 26–60.

- 26.Parsons TR, Maita Y, Lalli CM (1984) A manual of chemical and biological methods for seawater analysis. Pergamon Press. pp. 173.

- 27. Solorzano L (1969) Determination of ammonia in natural waters by the phenolhypochlorite method. Limnology and Oceanography 14: 799–801. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cowie GL, Hedges JI (1992) Improved amino acid quantification in environmental samples: Charge-matched recovery standards and reduced analysis time. Marine chemistry 37: 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Welschmeyer NA (1994) Fluorometric analysis of chlorophyll a in the presence of chlorophyll b and pheopigments. Limnology and Oceanography 39: 1985–1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guillard RRL (1973) Division rates. In: Stein JR, editor. Handbook of phycological methods: culture methods and growth measurements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 289–311.

- 31.Monod J (1942) Recherches sur la coissance des cultures Bactériennes. 2nd ed. Hermann, Paris. pp. 211.

- 32. Mulholland MR, Lee C (2009) Peptide hydrolysis and the uptake of dipeptides by phytoplankton. Limnology and Oceanography 54(3): 856–868. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anderson DM, Burkholder JM, Cochlan WP, Glibert PM, Gobler CJ, et al. (2008) Harmful algal blooms and eutrophication: Examining linkages from selected coastal regions of the United States. Harmful Algae 8: 39–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kana TM, Lomas MW, MacIntyre HL, Cornwell JC, Gobler CJ (2004) Stimulation of the brown tide organism, Aureococcus anophagefferens, by selective nutrient additions to in situ mesocosms. Harmful Algae 3: 377–388. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dugdale RC, Wilkerson FP, Hogue VE, Marchi A (2007) The role of ammonium and nitrate in spring bloom development in San Francisco Bay. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 73: 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mulholland MR, Lomas MW (2008) N uptake and assimilation. In: Capone DG, Bronk DA, Mulholland MR, Carpenter EJ, editors. Nitrogen in the marine environment. Academic Press. pp. 303–384.

- 37. Mulholland MR, Gobler CJ, Lee C (2002) Peptide hydrolysis, amino acid oxidation and nitrogen uptake in communities seasonally dominated by Aureococcus anophagefferens . Limnology and Oceanography 47: 1094–1108. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yu J, Tang D, Oh Im-Sang, Yao L (2007) Response of harmful algal blooms to environmental changes in Daya Bay, China. Terrestrial Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences 18(5): 1011–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seeyave S, Probyn TA, Pitcher GC, Lucas MI, Purdie DA (2009) Nitrogen nutrition in assemblages dominated by Pseudo-nitzschia spp., Alexandrium catenella and Dinophysis acuminata off the west coast of South Africa. Marine Ecology Progress Series 379: 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jeong HJ, Yoo YD, Kim JS, Seong KA, Kang NS, et al. (2010) Growth, feeding, and ecological roles of the mixotrophic and heterotrophic dinoflagellates in marine planktonic food webs. Ocean science journal 45 (2): 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Monod J (1950) La technique de la culture continue, théorie et applications. Annales de Institute Pasteur Paris 79(4): 390–410. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Guillard RRL, Kilham P, Jackson TA (1973) Kinetics of silicon-limited growth in the marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana Hasle and Heimdal ( = Cyclotella nana Hustedt). Journal of Phycology 9(3): 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Taylor GT, Gobler CJ, Sañudo-Wilhelmy SA (2006) Speciation and concentrations of dissolved nitrogen as determinants of brown tide Aureococcus anophagefferens bloom initiation. Marine Ecology Progress Series 312: 67–83. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gobler CJ, Burson A, Koch F, Tang Y, Mulholland MR (2012) The role of nitrogenous nutrients in the occurrence of harmful algal blooms caused by Cochlodinium polykrikoides in New York estuaries (USA). Harmful Algae 17: 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Healey FP (1980) Slope of the Monod equation as an indicator of advantage in nutrient competition. Microbial Ecology 5(4): 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tilman D (1977) Resource competition between planktonic algae: an experimental and theoretical approach. Ecology 58: 338–348. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hu Z, Xu N, Duan S, Li A, Zhang C (2010) Effects of urea on the growth of Phaeocystis globosa, Scrippsiella trochoidea, Skeletonema costatum . Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae 30(6): 1265–1270 (In Chinese, with English abstract).. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Allen CM, Jones ME (1964) Decomposition of carbamoyl phosphate in aqueous solution. Biochemistry 3: 1238–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Eppley RW, Thomas WH (1969) Comparison of half-saturation constants for growth and nitrate uptake of marine phytoplankton. Journal of Phycology 5: 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldman JC, Glibert PM (1983) Kinetics of inorganic nitrogen uptake by phytoplankton. In: Carpenter EJ, Capone DG, editors. Nitrogen in the marine environment. Academic Press, New York. pp. 233–274.

- 51. Harrison PJ, Parslow JS, Conway HL (1989) Determination of nutrient uptake kinetic parameters: a comparison of methods. Marine Ecology Progress Series 52: 301–312. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Herndon J, Cochlan WP (2007) Nitrogen utilization by the raphidophyte Heterosigma akashiwo: Growth and uptake kinetics in laboratory cultures. Harmful Algae 6: 260–270. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cochlan WP, Harrison PJ (1991) Uptake of nitrate ammonium and urea by nitrogen-starved cultures of Micromonas-pusilla (Prasinophyeae): transient responses. Journal of Phycology 27: 673–679. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cochlan WP, Herndon J, Kudela RM (2008) Inorganic and organic nitrogen uptake by the toxigenic diatom Pseudo-nitzschia australis (Bacillariophyceae). Harmful Algae 8: 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fan C, Glibert PM, Burkholder JM (2003) Characterization of the affinity for nitrogen, uptake kinetics, and environmental relationships for Prorocentrum minimumin natural blooms and laboaratory cultures. Harmful Algae 2: 283–299. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Smith REH, Kalff J (1982) Size dependent phosphorus uptake kinetics and cell quota in phytoplankton. Journal of Phycology 18: 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hein M, Pedersen MF, Sand-Jensen K (1995) Size-dependent nitrogen uptake in micro- and macroalgae. Marine Ecology Progress Series 118: 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Maguer J-F, L'Helguen S, Madec C, Labry C, Le Corre P (2007) Nitrogen uptake and assimilation kinetics in Alexandrium minutum (Dynophyceae): effects of N-limited growth rate on nitrate and ammonium interactions. Journal of Phycology 43: 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lomas MW, Glibert PM (1999) Interactions between NH4 + and NO3 − uptake and assimilation: comparison of diatoms and dinoflagellates at several growth temperatures. Marine Biology 133: 541–551. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cochlan WP, Bronk DA (2003) Effects of ammonium on nitrate utilization in the Ross Sea: implications for f-ratio estimates. In: DiTullio GR, Dunbar RB, editors. Biogeochemistry of the Ross Sea. AGU Antarctic Research Series 78. pp. 159–178.

- 61. Jauzein C, Loureiro S, Garcés E, Collos Y (2008) Interactions between ammonium and urea uptake by five strains of Alexandrium catenella (Dinophyceae) in culture. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 53: 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lindehoff E, Granéli E, Glibert PM (2011) Nitrogen uptake kinetics of Prymnesium parvum (Haptophyte). Harmful Algae 12: 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Li J, Glibert PM, Alexander JA (2011) Effects of ambient DIN:DIP ratio on the nitrogen uptake of harmful dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum and Prorocentrum donghaiense in turbidistat. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology 29(4): 746–761. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cochlan WP, Price NM, Harrison PJ (1991) Effects of irradiance on nitrogen uptake by phytoplankton: comparison of frontal and stratified communities. Marine Ecology Progress Series 69: 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kudela RM, Cochlan WP (2000) Nitrogen and carbon uptake kinetics and the influence of irradiance for a red tide bloom off southern California. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 21: 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Collos Y, Gagne C, Laabir M, Vaquer A, Cecchi P, et al. (2004) Nitrogenous nutrition of Alexandrium catenella (Dinophyceae) in cultures and in Thau Lagoon, southern France. Journal of Phycology 40: 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kudela R, Ryan J, Blakely M, Lane J, Peterson T (2008) Linking the physiology and ecology of Cochlodinium to better understand harmful algal bloom events: a comparative approach. Harmful Algae 7: 278–292. [Google Scholar]