Abstract

Context

Adolescent offspring of depressed parents are at high risk for experiencing depressive disorders themselves.

Objective

To determine whether the positive effects of a group cognitive-behavioral prevention (CBP) program extended to longer term (multi-year) follow-up.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A four-site, randomized, controlled trial enrolled 316 adolescent (ages 13-17 years) offspring of parents with current and/or prior depressive disorders; adolescents had histories of depression, current elevated depressive symptoms, or both.

Intervention

The CBP program consisted of 8 weekly, 90-minute group sessions followed by 6 monthly continuation sessions. Adolescents were randomly assigned to either the CBP program or usual care (UC).

Main Outcome Measure

The primary outcome was a probable or definite episode of depression (Depression Symptom Rating score ≥; 4) for at least 2 weeks through the month 33 follow-up evaluation.

Results

Over the 33-month follow-up period, youths in the CBP condition had significantly fewer onsets of depressive episodes compared to those in UC. Parental depression at baseline significantly moderated the intervention effect. When parents were not depressed at intake, CBP was superior to UC (NNT ratio=6), whereas when parents were actively depressed at baseline, average onset rates between CBP and UC were not significantly different. A three-way interaction among intervention, baseline parental depression, and site indicated that the impact of parental depression on intervention effectiveness varied across sites.

Conclusions

The CBP program showed significant sustained effects compared to usual care in preventing the onset of depressive episodes in at-risk youth over a nearly three-year period. Important next steps will be to strengthen the CBP intervention to further enhance its preventive effects, improve intervention outcomes when parents are currently depressed, and conduct larger implementation trials to test the broader public health impact of the CBP program for preventing depression in youth.

Keywords: depression, prevention, children, adolescents

Depression is a common, chronic, and impairing disorder with first onset often occurring during adolescence1 and affecting close to a quarter of all adults during their lifetime.2 The World Health Organization3 estimates that depression is the third leading cause of global disease, is projected to be the second leading cause by 2020, and will rank first in high income countries by 2030.4 Thus, depression is a major public health problem that requires the development, implementation, and evaluation of strategies for preventing its onset and recurrence.

In adolescents, depression is associated with impaired social relationships, lower educational attainment, and increased risk of suicide.5 The need for efficacious prevention approaches is widely recognized6,7 and particularly urgent given the low access to and uptake of appropriate treatments among depressed youth.8 Adolescence is a key window for preventive interventions given that the rate of depression significantly increases during this developmental period.9

Meta-analyses of youth depression prevention programs indicate modest effects,10-15 even among high-risk samples. Moreover, most prevention studies have focused on reducing depressive symptoms rather than preventing diagnosed depressive episodes. One notable exception, is the work of Clarke and colleagues, who in two trials16,17 found significantly fewer episodes of depression in high-risk youth receiving a cognitive-behavioral prevention (CBP) program as compared to youth receiving usual community services.

Building on this foundation, we conducted a large (N=316), multi-site randomized controlled trial (RCT) to examine the effectiveness of the Coping with Depression course for Adolescents (CWD-A)18 modified for prevention. Youth were at high risk due to their parent's history of depression (i.e., selective prevention)8,19,20 and the youth's own history of a prior depressive disorder or current depressive symptoms (i.e., indicated prevention).21,22 We sought to replicate the original prevention effect, demonstrate generalizability by delivering the program across different samples, settings, and geographic locations, and assess the robustness of the intervention to implementation by different investigative teams, thereby addressing the program's readiness for more widespread dissemination.

As reported previously,23 at the 9-month follow-up adolescents randomized to the CBP condition had significantly fewer episodes of depression (21.4%) compared to those in usual care (UC; 32.7%). Moreover, baseline parental depression significantly moderated the effect; for adolescents whose parents were not depressed at intake, CBP was significantly more effective in preventing subsequent depressive episodes than UC, whereas among youth whose parents were depressed at baseline, the CBP and UC conditions were not significantly different. No significant differences in outcome were found by site.

Few trials have measured and found significant prevention effects on diagnoses of depression, and even fewer have shown sustained effects for reducing episodes over several years.11,24 In the current intervention trial, we modified the CBP program by adding six monthly continuation sessions explicitly in an effort to extend the duration of the effects beyond those reported by Clarke and colleagues,17 who found that the initial significant effect of CBP versus UC was not sustained beyond 15 months. The primary purpose of the current report was to present the longer-term effects of the CBP program regarding the occurrence of depressive episodes during the interval from baseline through two years after the last continuation session. We hypothesized that adolescents in the CBP condition would have a lower hazard of depressive episodes across the 33-month follow-up period compared to youth in UC. Second, given our findings at 9-months,23 we tested whether baseline parental depression continued to moderate the longer-term effects of the CBP program versus UC.

Methods

Sample

Recruitment sample composition and assessment measures have been described in detail elsewhere.23 The sample included 316 adolescents who had at least one parent/caretaker who had had a depressive disorder (i.e., major depression; dysthymia) during the past three years, or had three or more depressive episodes or three or more years in a depressive episode during the child's life. At enrollment, 128 (45.4%) of these index parents were in an active depressive episode. Adolescent inclusion criteria were (a) 13-17 years old and (b) current subsyndromal depressive symptoms [i.e., score of ≥ 20 on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)]25 (n=63; 19.9%), or a prior history of a depressive disorder26 in remission for at least 2 months (n=175; 55.4%), or both (n=78; 24.7%). Thus for 80.1% of youth, we aimed to prevent episode recurrence.

Exclusion criteria for adolescents were a current DSM-IV mood disorder, currently receiving a therapeutic dose of an antidepressant medication (as defined by Brent et al., 2008),27 having ever had 8 or more sessions of CBT or Dialectical Behavior Therapy, or a diagnosis of bipolar I or schizophrenia in the youth or parents. Three youth were taking subtherapeutic doses of antidepressants at the time of enrollment.

Siblings were allowed to participate and were yoke-randomized to ensure assignment to the same condition. There were 33 sets of siblings (1 set of triplets). The sample was recruited from August 2003 through February 2006 from four sites located in Boston, Massachusetts; Nashville, Tennessee; Portland, Oregon; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.23 The institutional review boards of each site approved the study.

Procedures

Adolescents were randomized to either CBP (n=159) or UC (n=157) using standard techniques to ensure that the cells were balanced on age, sex, self-identified race and ethnicity, and inclusion criteria. Randomization resulted in a successful balance of these variables between conditions. Information about baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by condition is provided in our earlier report of the short-term (i.e., 9-month) outcomes and in Supplemental Table 1.23 All participants were considered part of the study once randomized (i.e., an intent-to-treat design). Parents and adolescents provided written informed consent and assent, respectively.

Intervention

The CBP program was a modification of the intervention used by Clarke and colleagues16,17,28 and emphasized cognitive restructuring and problem-solving. The version used here consisted of eight weekly, 90-minute (acute) and six monthly, 90-minute continuation sessions for mixed sex groups of 3 to 10 adolescents (mean group size=6.6, standard deviation [SD]=1.6). Therapists were at least Master's level clinicians trained and supervised by experienced Ph.D. clinicians. The interventions were delivered with fidelity across sites.23

Adolescents attended an average of 6.5 acute sessions (median=8.0, range 0-8), and an average of 3.8 continuation sessions (median=5.0, range 0-6). During the continuation sessions, cognitive and problem-solving strategies were reviewed and other skills (e.g., behavioral activation, relaxation, assertiveness) were introduced or expanded. In weeks 1 and 8, parent meetings were conducted to inform parents about the topics and skills being taught to their children. Parents of 76.4% of the adolescents in CBP attended the first session, and 70.9% attended the second.

Assessments

Assessments were conducted at baseline, after the acute intervention (month 2), after the continuation (month 9), and again at one year (month 21) and two years (month 33) post-continuation. Independent evaluators (IE) unaware of condition assignment conducted the follow-up assessments. IEs completed extensive training, received ongoing supervision, and demonstrated adequate inter-rater reliability in practice interviews and on a random subset of participant interviews.23

At baseline, parents were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders (SCID-1)29 to assess their current and past mood diagnoses and the total number and duration of their past depressive episodes; parents also completed the CES-D, a measure of the frequency of depressive symptoms during the prior week. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children, Present and Lifetime Version (KSADS-PL)30 was administered at baseline to parents and adolescents separately to obtain youths' current and past DSM-IV diagnoses.26 At each follow-up evaluation, parents and adolescents were interviewed about the teen with the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE),31 which yields information about the onset and offset of diagnosed depressive episodes since the previous assessment and provides a continuous rating of symptoms and impairment scored on a 6-point depression symptom rating (DSR) scale. The primary outcome of this RCT was a probable or definite episode of depression (i.e., DSR scores ≥; 4) for at least 2 weeks. Inter-rater reliability for this diagnostic variable in this sample was good (Kappa=0.92, 95% CI: 0.83-1.00).

At each assessment, adolescents also completed the CES-D, and the IEs rated the Children's Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R),32 the Child Global Assessment Scale (CGAS), and the Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA),33,34 which measured adolescents' mental health service use over the follow-up period. Youths in both conditions were permitted to initiate or continue non-study mental health services. When acute episodes of depression were identified at a follow-up, both parents and youths were informed and clinical referrals were provided.

Data Analytic Strategy

Survival analyses were used to assess the impact of CBP on the primary outcome (time to depression onset), and regression models were used to analyze dimensional depression symptom (CES-D, CDRS-R) trajectories over time. For both sets of analyses, a random-effects approach was adopted. Random-effects survival models (i.e., gamma frailty models) are designed to account for subject-to-subject heterogeneity in event times35 and often provide a better fit to the data than traditional fixed effects Cox models when such heterogeneity is significant.36,37 Following procedures described by Verbeke and Molenbergh,38 we tested the need for random effects models in our data by comparing the log likelihood between survival models with and without a random gamma frailty effect, adjusting the asymptotic null distribution for the difference of -2log-likelihood to a mixture of chi-squares (i.e., by setting the variance of the random effect to zero to account for parameter space restrictions). For all analyses, the gamma-frailty random effect model provided a better fit to the data than a fixed-effects Cox model; accordingly, results of random-effects survival models are presented. To adjust for multiple comparisons, we applied the False Discovery Rate method39 with the Yekutieli multiple-test procedure. The method was carried out with the q-value package in Stata 11.2.39-41 A q-value was calculated, and comparisons were considered significant when q<.05 (see Table 2).

Sibling correlations were adjusted in the mixed effects models of the CES-D and CDRS-R by including family as a random variable in the models. In the frailty model, we used an approach similar to the group-data method of Bauer and colleagues42 where we compared the fit of two models -- one that included youth with a participating sibling versus a model of youths without a sibling (i.e., singletons). No difference in fit was found between these two models (1638.4 vs. 1638.5 on the Akaike Information Corrected Criterion) indicating no significant effect due to separating the singletons from the siblings. Given the low rate of siblings overall (11.6%), we adopted the more parsimonious analysis that did not specifically model sibling effects.

To benchmark the clinical significance of the findings, we computed the number-needed-to-treat (NNT) ratio, a metric used in evidence-based medicine to indicate the number of persons that would need to receive the intervention in order to prevent one additional onset of the disorder in question.43 In our earlier report through 9 months,23 we found an NNT = 9 for the main effect of CBP. The current analyses again (a) examined the main effect of the intervention, (b) tested whether baseline parental depression status was a significant moderator, and (c) added site and its interactions to the analytic models.

Results

Sample Characteristics and Retention

Sample characteristics at baseline

As is common in multi-site trials, differences by site were found on some baseline variables: demographics, chronicity of parental depression, level of adolescent depressive symptoms at intake, and in the proportion of youth who had a previous history of a depressive episode (Supplemental Table 2). Importantly, however, the CBP and UC conditions did not differ significantly on any baseline demographic or clinical variables across sites (Supplemental Table 1).23

Sample retention

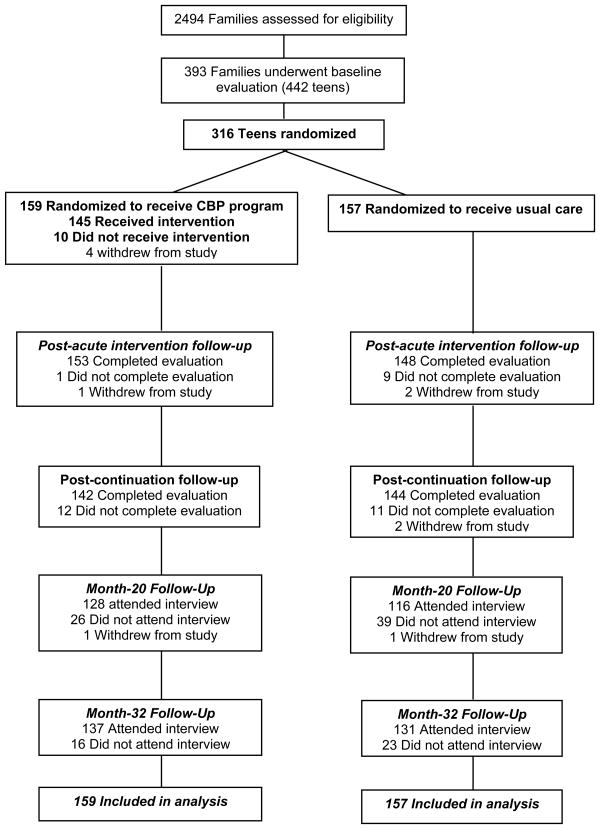

baseline (SD=24), range: 119-279 weeks]; given this wide range, we truncated the data at 150 weeks, which corresponds to the median time of the interview. Figure 1 presents the Consort Diagram through this follow-up period. Overall, sample retention to 33 months was high, and there was no differential attrition by condition, either across or within sites [CBP: 137/159 (86.2%) vs. UC: 131/157 (83.4%), χ21=0.46, p=.50]. Retention rates varied significantly across sites (χ23=58.21, p<.001, range 61.5% to 100%). Retained and missing participants differed on 3 of 23 variables: retained participants had lower baseline CES-D scores [18.2 (SD=9.3) vs. 21.4 (SD=9.4), t(314)=2.20, p=.03], higher parent education [190/237 (80.2%) vs. 28/45 (62.2%), χ21= 6.94, p=.008], and higher SES [46.3 (SD=12.1) vs. 42.6 (SD=11.1), t(313)= -2.01, p=.046]. When baseline CES-D, parent education, and SES were covaried in the analyses, site differences in attrition rates remained.

Figure 1. Study Flow of Participants: Screening to Analysis.

Intervention Effects: Time to Depression Onset

Main effect of CBP versus UC

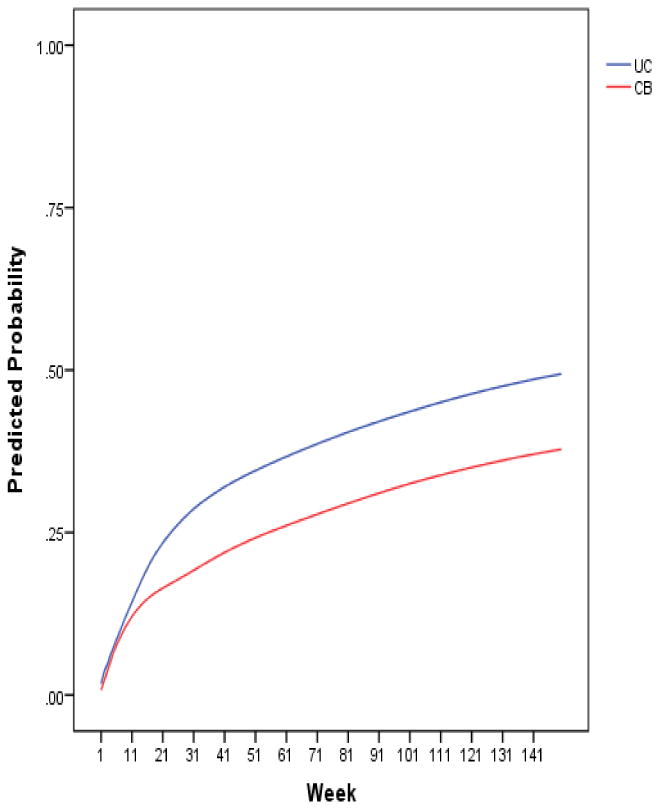

The overall main effect for the intervention was significant [β=-0.63 (se=0.31), t(309)=-2.04, p=.04]. For the sample as a whole, the onset rate was slower for CBP compared to UC. Over the 33-month follow-up, 36.8% of adolescents in CBP had a depression onset versus 47.7% of youth in the UC condition, corresponding to an NNT ratio of 10 (95% CI: 5 to 2624).

Moderating effect of baseline parental depression

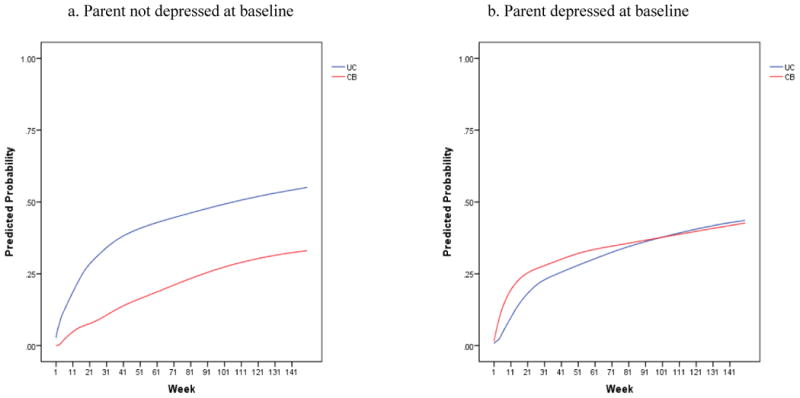

We next added parental depression to the model, and found, similar to the results at 9-months,23 that baseline parental depression significantly moderated the effect of the intervention on the onset of depression in adolescents across the 33-month interval [β=1.39 (se=0.44), t(309)=3.16, p=.002]. CBP was superior to UC when parents were not currently depressed at intake [β=1.18 (se=0.34), t(309)=3.46, p=.001], whereas when parents were depressed at baseline, average onset rates between CBP and UC did not differ [β=0.24 (se=0.32), t(309)=0.75, p=.45]. In families with no current baseline parental depression, on average, 32.1% of youth in CBP experienced an onset of depression compared to 51.9% of youth in UC, corresponding to an NNT ratio of 6 (95% CI: 3 to 23). In families with parental depression at baseline, differences in onset rates between conditions were negligible (CBP: 41.6% vs. UC: 43.4%), with an estimated NNT of 54. All results remained unchanged when analyses were rerun excluding the three adolescents (2 in CBP; 1 in UC) taking subtherapeutic doses of antidepressants at study enrollment.

Site effects and interactions

We computed an omnibus random-effects survival model that tested main effects and all higher order interactions for condition (CBP vs. UC), baseline parental depression (ParDep), and site. Table 1 shows the full specification of this model, and Table 2 presents the pooled data and the targeted contrasts based on the full model. This omnibus model yielded a significant main effect for the intervention favoring CBP over UC (see Figure 2) and an interaction in the targeted contrasts indicating that this effect was conditioned upon parental depression at baseline (see Figure 3). Significant two- and three-way interactions were found between condition and site and among condition, ParDep, and site, respectively.

Table 1. Frailty Survival Analysis.

| Estimate | SE | Test | P | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.67 | 0.16 | t= 29.39 | <.001 | 4.35 to 4.98 |

| Condition | -2.46 | 0.19 | t= -13.25 | <.001 | -2.83 to -2.10 |

| Parental Depression | -1.51 | 0.24 | t= -6.36 | <.001 | -1.98 to -1.04 |

| Site∧ | F= 58.47 | <.001 | |||

| Site 1* | -0.83 | 0.17 | t= -4.88 | <.001 | -1.17 to -0.50 |

| Site 3* | -2.15 | 0.22 | t=-9.69 | <.001 | -2.59 to -1.71 |

| Site 4* | 0.54 | 0.27 | t=2.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 to 1.06 |

| Condition by Parental Depression | 0.59 | 0.41 | t= 1.44 | 0.15 | -0.22 to 1.40 |

| Condition by Site∧ | F= 37.23 | <.001 | |||

| Condition by Site 1 | 1.35 | 0.29 | t= 4.64 | <.001 | 0.78 to 1.92 |

| Condition by Site 3 | 3.01 | 0.29 | t= 10.55 | <.001 | 2.45 to 3.57 |

| Condition by Site 4 | 1.35 | 0.25 | t= 5.45 | <.001 | 0.86 to 1.84 |

| Parental Depression by Site∧ | F= 73.79 | <.001 | |||

| Parental Depression by Site 1 | 2.61 | 0.28 | t= 9.30 | <.001 | 2.06 to 3.16 |

| Parental Depression by Site 3 | 1.34 | 0.33 | t= 4.03 | <.001 | 0.69 to 2.00 |

| Parental Depression by Site 4 | -1.45 | 0.33 | t= -4.34 | <.001 | -2.11 to -0.80 |

| Condition by ParDep by Site∧ | F= 13.43 | <.001 | |||

| Condition by ParDep by Site 1 | -0.52 | 0.49 | t= -1.06 | 0.29 | -1.49 to 0.45 |

| Condition by ParDep by Site 3 | 0.15 | 0.51 | t= 0.30 | 0.77 | -0.85 to 1.15 |

| Condition by ParDep by Site 4 | 2.12 | 0.52 | t= 4.08 | <.001 | 1.10 to 3.14 |

| Frailty (gamma) | 3.84 | 0.39 | t= 9.97 | <.001 | 3.08 to 4.60 |

| Random effect (logsig) | 0.75 | 0.02 | t= 32.04 | <.001 | 0.71 to 0.80 |

Note: Regression coefficients represent complementary log-hazard coefficient contribution for each effect.

Dummy variables for Site. Site 2 is the reference group.

ParDep = parental depression at baseline; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval

Degrees of freedom for these analyses = 3, 309; for all other analyses degrees of freedom = 309

Table 2. Targeted Contrasts for Interaction Effects.

| β | SE | t | P | q | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Main Effect | 0.52 | 0.08 | 6.72 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Intervention Effect: Site1 | 1.08 | 0.14 | 7.91 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Intervention Effect: Site2 | 2.17 | 0.21 | 10.36 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Intervention Effect: Site3 | -0.92 | 0.13 | -7.02 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Intervention Effect: Site4 | -0.25 | 0.14 | -1.73 | .08 | .34 |

| Intervention By ParDep: Pooled | -1.03 | 0.16 | -6.63 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Intervention X ParDep: Site1 | -0.07 | 0.27 | -0.26 | .79 | >.99 |

| Intervention X ParDep: Site2 | -0.59 | 0.41 | -1.44 | .15 | .60 |

| Intervention X ParDep: Site3 | -0.74 | 0.30 | -2.5 | .01 | .04 |

| Intervention X ParDep: Site4 | -2.71 | 0.32 | -8.41 | <.001 | <.001 |

| CBP/UC-Contrast Pooled Site – No ParDep | 1.03 | 0.10 | 10.76 | <.001 | <.001 |

| CBP/UC-Contrast Pooled Site - ParDep | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.04 | .97 | >.99 |

| CBP/UC-Contrast Site1 – No ParDep | 1.11 | 0.22 | 5.00 | <.001 | <.001 |

| CBP/UC-Contrast Site1 - ParDep | 1.04 | 0.15 | 6.79 | <.001 | <.001 |

| CBP/UC-Contrast Site2 – No ParDep | 2.46 | 0.19 | 13.25 | <.001 | <.001 |

| CBP/UC-Contrast Site2 - ParDep | 1.87 | 0.37 | 5.04 | <.001 | <.001 |

| CBP/UC-Contrast Site3 – No ParDep | -0.55 | 0.21 | -2.62 | .009 | .04 |

| CBP/UC-Contrast Site3 - ParDep | -1.29 | 0.19 | -6.95 | <.001 | <.001 |

| CBP/UC-Contrast Site4 – No ParDep | 1.11 | 0.17 | 6.64 | <.001 | <.001 |

| CBP/UC-Contrast Site4 - ParDep | -1.60 | 0.25 | -6.33 | <.001 | <.001 |

ParDep = parental depression at baseline; SE = standard error; CBP = Cognitive-behavioral prevention program; UC = Usual care;

Figure 2. Risk of incident depression1 by intervention condition.

1“Incident depression” was defined as a probable or definite depressive episode (i.e., Depression Symptom Rating ≥ 4).

Figure 3. Comparison of CBP versus UC for adolescents whose parents were not depressed at baseline and for those whose parents were depressed at baseline.

The intervention condition by site interaction was due to superior effects for CBP at two sites, no significant difference between CBP and UC at a third site, and a significant effect for UC at a fourth site. This latter site had a significantly lower overall onset rate across both the CBP and UC conditions as compared to the other three sites (31.3% vs. 46.1%, χ21=5.35, p=.02). Thus, the effects at this site were being driven by a significantly smaller number of youths with depression onsets relative to the other sites; therefore, the findings at this site should be interpreted with caution.

The significant interaction among intervention, baseline parental depression, and site indicated that the impact of parental depression on intervention effectiveness varied across sites. In the absence of parental depression at intake, CBP was better than UC at three sites and worse at the fourth. In the presence of baseline parental depression, CBP was better than UC at two sites and worse at two others. Interestingly, differences favoring CBP over UC were robust to parental depression at the two sites that had minimal attrition (0% and 2.6%); differences favoring UC over CBP were found at the sites with higher attrition (20% and 39.5%). Finally, although some characteristics differed across sites, incorporating these variables into the survival models did not account for site effects.

Intervention Effects: Secondary Outcomes

Changes in youths' depressive symptoms (i.e., CES-D, CDRS-R) were analyzed using random-effects regression models for continuous data. For the CES-D, the main effect of intervention was not significant, but similar to our short-term results,23 the interaction of condition x time x baseline parental depression was significant; β=-1.55, 95% CI:-3.00 to -0.09, z= -2.08, p=.04). Paired comparisons indicated that among adolescents whose parents were depressed at baseline, the CES-D trajectory was significantly worse for youth in UC as compared to those in CBP (β=1.21, 95% CI: 0.16 to 2.26, z=2.25, p=.02). Other pairwise comparisons within this interaction were not significant. The condition x time x site interaction was not significant, indicating that the pattern of intervention effects on the CES-D was consistent across sites. For the CDRS-R, the main effect of intervention, the moderating effect of baseline parental depression, and the intervention x time x site interaction were not significant.

Service Utilization

Adolescents randomized to the CBP program versus UC did not differ significantly in any type of mental health service use from baseline through the 33-month follow-up period (Supplemental Table 3). Thus, the significant differences in the longer-term outcomes between adolescents in CBP versus UC likely were not due to differences in treatment during this time period. Finally, we found that although some service utilization categories differed by site, incorporating these service variables into the survival models altered neither the main effect of the intervention nor the moderating effect of baseline parental depression.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that, on average, the positive effects of the cognitive-behavioral program for preventing depressive episodes in at-risk offspring of depressed parents persisted for nearly three years, such that one additional onset was prevented for every ten participants. The recent IOM report7 asserted that long-term effects are essential for establishing the value of prevention. Enduring effects have been rare with regard to preventing diagnosed depressive disorders in youth.11,44 The current study demonstrated the durability of the effects of the CBP program for preventing depressive disorders in at least some high-risk adolescents.

The superior effect of CBP over UC in rates of depression onsets remained statistically significant when baseline parental depression was included as a moderator. Similar to the 9-month results,23 when parents were not depressed at baseline, CBP was significantly better than UC; one additional onset was prevented for every six adolescents in the CBP condition. When parents were depressed at baseline, however, differences in onset rates between CBP and UC were negligible, with only one additional onset prevented for every 54 participants. Thus, the overall effects of the CBP program compared to UC were conditioned on parent's depression at intake.

Such an attenuated effect of the CBP program in the presence of current parental depression is consistent with studies that have shown that CB interventions for various youth disorders work less well when a parent is actively depressed.45-46 Exactly why parental depression at the time of study enrollment was related to differential intervention effects is a matter of conjecture. Perhaps active parental depression directly affected intervention uptake or utilization, or it represents a marker of some third variable such as shared genetic vulnerability, a more chronic or recurrent course of parental depression, disrupted parenting, or more extensive exposure to stressful life events. The moderator effect of baseline parental depression also could have been an artifact of differences in sample composition or differential attrition across sites.

If current parental depression somehow suppresses intervention effectiveness, then the CBP program might be best delivered when parents are not acutely depressed. This may mean waiting until the parent's depression has resolved or actively treating parents' current depression prior to or concurrently with providing the CBP program to their children. Large scale RCTs are needed to test the direct impact of treating parents' depression on children's general adjustment47 and on their response to preventive interventions. If current parental depression is a marker of different causal processes, however, then other steps will be needed to detect and target the mechanisms that underlie youth onsets.48,49

From a public policy perspective, the magnitude of the observed effects was in line with other recommended evidence-based medical interventions. When parents are not currently depressed, only six at-risk youth would need to receive CBP to improve upon outcomes in usual care, which is a noteworthy NNT ratio. Even within this “best” outcome group, however, almost one third of these adolescents still experienced a depressive episode during the 33-month follow-up period. One reason for such high onset rates might be that the majority of youth in this sample had had a prior depressive episode; that is, they were experiencing recurrent episodes. In the current study, youth were enrolled based on youth current symptoms or a prior history of depression in addition to parental depression, whereas most other depression prevention trials have recruited participants on the basis of either child characteristics or familial risk6,20,50. The relatively high rate of onsets of depressive episodes found even among youth who had received the CBP intervention and whose parents were not currently depressed suggests that a more comprehensive range of services may need to be provided to such at-risk youth and their families.

Another aim of this study was to test the generalizability and robustness of the CBP program when implemented at diverse settings by different investigators to determine the program's readiness for more widespread dissemination. Results indicated that the relation between the intervention condition and baseline parental depression was not consistent across sites. The clearest evidence of the enduring effect of CBP as compared to UC, regardless of baseline parental depression, was found at the two sites with minimal attrition, whereas the findings were more variable and baseline parental depression mattered at the two sites with higher attrition. This differential retention rate across sites might partially account for the significant subject-to-subject heterogeneity in survival rates observed here. If the moderating effect of parental depression is related to attrition or other sample characteristics, then pragmatic steps will be needed to ensure that youth stay involved in the intervention. The fact that site moderated the intervention effect suggests that larger-scale dissemination trials are still needed to understand the full range of setting, provider, and organizational characteristics that impact the effectiveness and ultimate uptake of the program in practice.

The recent IOM volume on depression and parenting6 strongly recommended combining treatments for reducing parents' symptoms with interventions aimed at improving their parenting. Indeed, prevention programs that enhance parenting skills and the quality of the parent-child relationship have shown positive effects on youth outcomes,20,51,52 and lower rates of depression in adolescents24 and adults53 in particular. Although the current study found that compared to UC, the CBP program significantly reduced the hazard of depressive episodes, the addition of an intervention that directly targets parents' behaviors toward their offspring might enhance youths' outcomes further and for even longer intervals as suggested by the more sustained (i.e., 2 to 7 years) effects found in some prevention programs that have included a parenting component.24,53 Sustained effects also might be enhanced by including additional booster sessions as has been found in some treatment studies aimed at preventing relapse,24,54-56 or by using a “family check-up” approach57 as a way to maintain the positive effects of the CBP intervention.

The CBP program used in this study is a relatively straightforward intervention that can be delivered by clinicians with modest training in CB approaches. From a public health perspective, interventions that are likely to be widely adopted are clear-cut, easily taught, and can be implemented in a variety of settings,7,20 all of which characterize this CBP intervention. Thus, for offspring of depressed parents, the CBP program is user-friendly and effective, particularly when parents are not currently depressed.

Limitations of this study should be noted. First, the current trial focused on the prevention of the onset of new depressive episodes, but not necessarily first episodes given that 80% of the sample had had prior depression. Second, sites differed in attrition, but we were unable to explain these differences based on the available data. Sites also likely varied on a range of characteristics not assessed in this study, such as regional differences in the availability and acceptability of mental health services. Third, a small subset of adolescents reported taking antidepressants after randomization, but this did not differ between the two conditions, and therefore cannot explain the significant prevention effect.

Examination of CBP and related interventions in different settings (e.g., primary care; schools) and with other samples (e.g., youth with anxiety; different cultural groups) should proceed, albeit with caution, before attempting widespread dissemination. More information is needed about the degree of implementation “scaffolding” that is required to reduce site and program delivery variation. Finally, the contribution of individual and family differences in response to the program should be explored to facilitate the development of more robust and personalized preventive intervention strategies. In summary, the current randomized trial demonstrated an enduring preventive effect of CBP with at-risk youth, particularly when their parents were not in an active depressive episode at the time of intervention initiation. More information is needed regarding what individual and contextual factors enhance or limit the efficacy of this intervention, and the mechanisms underlying these differential effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health grants (R01 MH064735; R01 MH64541; R01 MH64503; R01 MH64717), NICHD Grant P30HD15052, and by the National Center for Research Resources (UL1 RR024975-01), now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Grant 2 UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding/Support: The project was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health grants (R01MH064735; R01 MH64541; R01 MH64503; R01 MH64717) and by the National Center for Research Resources (UL1 RR024975-01), now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Grant 2 UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Additional contributions: Jamie Zelazny, MPH, RN, and Tim Pitts, MEd, University of Pittsburgh; Laurel Duncan, BA, Beth Donaghey, MA, and Liz Ezell, MA, Vanderbilt University; Kevin Rogers, MA, Stephanie Hertert, MEd, and Kristina Booker, BA, Kaiser Permanente; and Phyllis Rothberg, LICSW, Judge Baker Children's Center/Children's Hospital, provided assistance with study coordination. Nadine Melhem, PhD, Deena Battista, PhD, and Yuan Brustoloni, MS, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and John Dickerson, MS, Kaiser Permanente, assisted with statistical analyses. Brian McKain, MSN, University of Pittsburgh; Mary Jo Coiro, PhD, Vanderbilt University; Alison Firemark, MA, Bobbi Jo Yarborough, MA, and Sue Leung, MA, Kaiser Permanente; Mary Kate Little, LICSW, and Katherine Ginnis, LICSW, Judge Baker Children's Center/Children's Hospital, served as study therapists. Sharon Doyle Herzer, RN, MS, Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Tennessee, facilitated access to potential participants. All of the above mentioned individuals were monetarily compensated for their contributions. Eugene D'Angelo, PhD, Boston Children's Hospital, provided consultation. C. Hendricks Brown, PhD, and Irwin Sandler, PhD, reviewed and commented on drafts of the manuscript. We thank all of the participating parents and adolescents and independent evaluators. We also thank Don Guthrie, PhD, Joan Asarnow, PhD, Connie Hammen, PhD, and Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus, PhD, for serving on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

Dr. David Brent is a member of the Editorial Board of UpToDate and receives royalties from the Guilford Press. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of general psychiatry. 1998 Jan;55(1):56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Archives of general psychiatry. 1994;51:8–18. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006 May 27;367(9524):1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS medicine. 2006 Nov;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibb SJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Burden of psychiatric disorder in young adulthood and life outcomes at age 30. Br J Psychiatry. 2010 Aug;197:122–127. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Research Council, Institute of Medicine. Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices, and the Healthy Development of Children, Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington DC: 2009. Depression in Parents, Parenting, and Children: Opportunities to Improve Identification, Treatment, and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Research Council, Institute of Medicine. Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders and Substance Abuse Among Children, Youth, and Young Adults: Research Advances and Promising Interventions. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: 2009. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA. 1997 Jan 22-29;277(4):333–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1998 Feb;107(1):128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P. A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2009 Jun;77(3):486–503. doi: 10.1037/a0015168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brunwasser SM, Gillham JE, Kim ES. A meta-analytic review of the Penn Resiliency Program's effect on depressive symptoms. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2009 Dec;77(6):1042–1054. doi: 10.1037/a0017671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horowitz JL, Garber J. The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2006 Jun;74(3):401–415. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garber J. Depression in children and adolescents: linking risk research and prevention. American journal of preventive medicine. 2006 Dec;31(6 Suppl 1):S104–125. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jane-Llopis E, Hosman C, Jenkins R, Anderson P. Predictors of efficacy in depression prevention programmes. Meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2003 Nov;183:384–397. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.5.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merry SN, Hetrick SE, Cox GR, Brudevold-Iversen T, Bir JJ, McDowell H. Psychological and educational interventions for preventing depression in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(12):CD003380. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003380.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke GN, Hawkins W, Murphy M, Sheeber LB, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Targeted prevention of unipolar depressive disorder in an at-risk sample of high school adolescents: a randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995 Mar;34(3):312–321. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke GN, Hornbrook M, Lynch F, et al. A randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention for preventing depression in adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Archives of general psychiatry. 2001 Dec;58(12):1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Rohde P, Hops H, Seeley JR. A course in coping: A cognitive-behavioral approach to the treatment of adolescent depression. In: Hibbs ED, Jensen PS, editors. Psychosocial Treatments for Children and Adolescent Disorders: Empirically Based Strategies for Clinical Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 1996. pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H. Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. The American journal of psychiatry. 2006 Jun;163(6):1001–1008. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR, O'Connor EE. Transmission and prevention of mood disorders among children of affectively ill parents: a review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011 Nov;50(11):1098–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: I. Continuity into young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999 Jan;38(1):56–63. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199901000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rao U, Hammen C, Daley SE. Continuity of depression during the transition to adulthood: a 5-year longitudinal study of young women. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999 Jul;38(7):908–915. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garber J, Clarke GN, Weersing VR, et al. Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009 Jun 3;301(21):2215–2224. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Compas BE, Forehand R, Thigpen JC, et al. Family group cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention for families of depressed parents: 18- and 24-month outcomes. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2011 Aug;79(4):488–499. doi: 10.1037/a0024254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radloff L. The Use of the Center for EpidemiologicStudies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20(2):149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brent DA, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: The TORDIA randomized control trial. J Amer Med Assoc. 2008;299(991-913) doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke GN, Lewinsohn PM, Hops H. Instructor's Manual for the Adolescent Coping with Depression Course. Portland, Oregon: Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 29.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IVAxis I Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) Version 2.0. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997 Jul;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, et al. The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation. A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of general psychiatry. 1987 Jun;44(6):540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poznanski EO, Grossman JA, Buchsbaum Y, Banegas M, Freeman L, Gibbons R. Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the children's depression rating scale. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1984 Mar;23(2):191–197. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ascher BH, Farmer EM, Burns BJ, Angold A. The Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA): description and psychometrics. J Emot Behav Disord. 1996;4(1):12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farmer EM, Angold A, Burns BJ, Costello EJ. Reliability of self-reported service use: Test-retest consistency of children's responses to the Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA) Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1994;3:307–325. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark TG, Bradburn MJ, Love SB, Altman DG. Survival analysis part IV: further concepts and methods in survival analysis. Br J Cancer. 2003 Sep 1;89(5):781–786. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chastang C, Byar D, Piantadosi S. A quantitative study of the bias in estimating the treatment effect caused by omitting a balanced covariate in survival models. Stat Med. 1988 Dec;7(12):1243–1255. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780071205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmoor C, Schumacher M. Effects of covariate omission and categorization when analysing randomized trials with the Cox model. Stat Med. 1997 Jan 15;16(1-3):225–237. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970215)16:3<225::aid-sim482>3.0.co;2-c. Feb 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data. New York: Spinger-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Storey JD. The positive false discovery rate: A Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newson R ALSPAC Study Team. Multiple-test procedures and smile plots. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newson R Team AS. Software update: st0035_1: Multiple-test procedures and smile plots. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bauer DJ, Sterba SK, Hallfors DD. Evaluating Group-Based Interventions When Control Participants Are Ungrouped. Multivariate behavioral research. 2008 Apr 2;43(2):210–236. doi: 10.1080/00273170802034810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biological psychiatry. 2006 Jun 1;59(11):990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gladstone TR, Beardslee WR. The prevention of depression in children and adolescents: a review. Can J Psychiatry. 2009 Apr;54(4):212–221. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brent DA, Kolko DJ, Birmaher B, et al. Predictors of treatment efficacy in a clinical trial of three psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998 Sep;37(9):906–914. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley J. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychological Review. 1998;18:765–794. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swartz HA, Frank E, Zuckoff A, et al. Brief interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed mothers whose children are receiving psychiatric treatment. The American journal of psychiatry. 2008 Sep;165(9):1155–1162. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garber J, Ciesla JA, McCauley E, Diamond GM, Schloredt KA. Remission of Depression in Parents: Links to Healthy Functioning in their Children. Child development. 2011;82(1):244–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne P, Talati A, et al. Children of depressed mothers 1 year after the initiation of maternal treatment: findings from the STAR*D-Child Study. The American journal of psychiatry. 2008 Sep;165(9):1136–1147. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR. Prevention of childhood depression: recent findings and future prospects. Biological psychiatry. 2001 Jun 15;49(12):1101–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Compas BE, Champion JE, Forehand R, et al. Coping and parenting: Mediators of 12-month outcomes of a family group cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention with families of depressed parents. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2010 Oct;78(5):623–634. doi: 10.1037/a0020459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA, et al. The family bereavement program: efficacy evaluation of a theory-based prevention program for parentally bereaved children and adolescents. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2003 Jun;71(3):587–600. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandler I, Ayers TS, Tein JY, et al. Six-year follow-up of a preventive intervention for parentally bereaved youths: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010 Oct;164(10):907–914. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kroll I, Harrington R, Jayson D, Fraser J, Gowers S. Pilot Study of Continuation Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Major Depression in Adolescent Psychiatry Patients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1156–1161. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mathew KI, Whitford HS, Kenny MA, Denson IA. The Long-Term Effects of Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy as a Relapse Prevention Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2010;38:561–576. doi: 10.1017/S135246581000010X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, Finos L, Conti S, Grandi S. Six-year outcome of cognitive behavior therapy for prevention of recurrent depression. The American journal of psychiatry. 2004 Oct;161(10):1872–1876. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dishion TJ, Shaw D, Connell A, Gardner F, Weaver C, Wilson M. The family check-up with high-risk indigent families: preventing problem behavior by increasing parents' positive behavior support in early childhood. Child development. 2008 Sep-Oct;79(5):1395–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.