Abstract

Current evidence suggests suceptibility of both the substantia nigra and striatum to exposure to components of air pollution. Further, air pollution has been associated with increased risk of PD diagnsosis in humans or PD-like pathology in animals. This study examined whether exposure of mice to concentrated ambient ultrafine particles (CAPS; <100 nm diameter) during the first two weeks of life would alter susceptibility to induction of the Parkinson’s disease phenyotype (PDP) in a pesticide-based paraquat and maneb (PQ+MB) model during adulthood utilizing i.p. injections of 10 mg/kg PQ and 30 mg/kg MB 2× per week for 6 weeks. Evidence of CAPS-induced enhancement of the PQ+MB PDP was limited primarily to delayed recovery of locomotor activity 24 post injection of PQ+MB that could be related to alterations in striatal GABA inhibitory function. Absence of more extensive interactions might also reflect the finding that CAPS and PQ+MB appeared to differentially target the nigrostriatal dopamine and amino acid systems, with CAPS impacting striatum and PQ+MB impacting dopamine-glutamate function in midbrain; both CAPS and PQ+MB elevated glutamate levels in these specific regions, consistent with potential excitotoxicity. These findings demonstrate the ability of postnatal CAPS to produce locomotor dysfunction and dopaminergic and glutamateric changes, independent of PQ+MB, in brain regions involved in the PDP.

Keywords: Parkinson’s Disease, paraquat, maneb, particulate matter, ultrafine particles, dopamine, glutamate, locomotor activity, dopamine neurons

1. INTRODUCTION

Exposure to ultrafine particulate matter (UFP), identified as potentially the most toxic constituent of air polltuion (Oberdorster 2000), is both pervasive and ubiquitous and life-long. The adverse cardiopulmonary impacts of air pollution have been extensively described. However, accumulating evidence indicates that air pollutants also target the central nervous system (CNS), which could also suggest that such exposures serve as risk factors for CNS diseases and disorders. Particulate matter, one of many components of ambient outdoor air pollution, has been shown to cause elevation in cytokines and oxidative stress in the brain (Campbell et al. 2005; Campbell et al. 2009); similar responses occur in brains of animals exposed to diesel exhaust (Gerlofs-Nijland et al. 2010; Levesque et al. 2011a; Levesque et al. 2011b). In addition, air pollutants have also been shown to induce microglia activation (Levesque et al. 2011b) and cause dysfunction of dopamine neurons in vitro (Levesque et al. 2013). The midbrain and the striatum have been reported to be particularly susceptible to air pollution exposure. The midbrain, including the substantia nigra, shows the greatest microglial response to diesel exhaust (Guerra et al. 2013; Levesque et al. 2011b), whereas particulate matter in the striatum generates increases in markers of oxidative stress, inflammation, and unfolded protein response (Guerra et al. 2013). In one study, chronic exposure to living in urban Mexico city was associated with increased misfolding of hyperphosphorylated tau, beta-amlyoid, and alpha-synuclein, potential markers of early neurodegeneration in children; however, interpretation is limited due to lack of information regarding actual exposure to particulate matter and other potential confounding environmental exposures in Mexico City. Additionally, industrial emissions of manganese measured in total suspended particulate in Halmilton, Ontario, Canada was associated with increased physican-diagnosed Parkinson’s disease (Finkelstein and Jerrett 2007). Given the evidence suggesting suceptibility of both the substantia nigra and striatum to exposure to components of air pollution, coupled with indications of air pollutant exposure with increased risk of PD diagnsosis in humans or PD-like pathology in animals, this study sought to determine whether exposure to concentrated ambient ultrafine particles (CAPS) during the first two weeks of life would alter susceptibility to induction of the Parkinson’s Disease phenyotype (PDP) using the pesticide-based paraquat and maneb (PQ+MB) model of the PDP (Thiruchelvam et al. 2000b).

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that results in depeltion of dopaminergic (DAergic) neuron cell bodies in the substantia nigra pars compacta with loss of tyrosine hydroxylase in the projecting DAergic neurons (the striatum) of those cell bodies. In addtion, loss of dopamine, a neurotransmitter critical for mediating motor behaviors disrupted in PD, is observed in the striatum of PD patients. Intracytoplasmic inclusions, called Lewy bodies, containing α-synuclein and parkin, are often observed in the post-mortem PD brain. Genetics alone account for a small proportion of PD cases and environmental factors, such as exposure to pesticides, including paraquat and maneb, have been widely implicated in idiopathic PD pathogenesis (Costello et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2011). Paraquat is taken up by the brain from which it is cleared relatively slowly (Breckenridge et al. 2013). Positive associations between idiopathic PD and rural living have been replicated many times (Priyadarshi et al. 2001; Rajput et al. 1987; Tanner et al. 1987). Interestingly, agricultural operations, that are likely to occur in non-urban (i.e. rural) areas are sources of air pollution, including particulate matter exposures (McCubbin et al. 2002), albeit, the particulate matter due to agricultural work is likely to be of a different size and chemical composition than the UFP studied here.

Although PD is often thought of as a disease of ageing, with much research focused on environmental exposures occuring in aduthood; the perinatal environment may predispose the nigrostriatal (i.e. substantia nigra pars compacta and striatum) dopamine system to concurrent or future damage (Barlow et al. 2004; Cory-Slechta et al. 2005). Indeed, animal studies using neonatal exposure to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to model immune activation, show increased suscepility of the substantia nigra to the pesticide rotenone (Cai et al. 2013; Fan et al. 2011; Tien et al. 2013). Given the ability of air pollution to evoke a neuroinflammatory response in the brain, likley similar to that of LPS, this study hypothesized that animals exposed to concentrated ambient ultrafine particles during early postnatal life, a period of rapid brain growth and differentiation (Bandeira et al. 2009), would be be more susceptible to the PDP-inducing effects of PQ+MB as manifested by enhanced susceptibility to the locomotor reducing effects of PQ+MB and degeneration of DAergic neurons in the nigrostriatal dopamine tract.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Animal and Experimental Design

Male and Female C57Bl6/j mice purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) were bred in monogamous pairs. Males and females were paired for 3 days, after which males were removed from the cage and pregnant dams were housed singly until litters were weaned. Allocation of pups into treatment groups was counterbalanced against litter size; to preclude litter-specific effects, no more than a single pup per litter per treatment group, with a single pup per litter, used when possible. Upon weaning at postnatal day 25, offspring were housed 3–4 per cage under a 12-hr light/dark cycle maintained at 72°F. Given the male-biased incidence of Parkinson’s disease (Haaxma et al. 2007; Wooten et al. 2004), only male mice were used in this study.

Weanling pups were removed from dams and exposed to CAPS or HEPA-filtered (99.99% effective) room air in compartmentalized individual whole-body inhalation chambers from PND 4–7 and 10–13 for 4 hr/day between 0700–1300 hrs, times corresponding to peak vehicular traffic near the ambient air intake value of the Harvard University Concentrated Ambient Particle System (HUCAPS) that is described elsewhere (Allen et al, 2013). CAPS- and air-exposed mice underwent identical experimental manipulations aside from exposure. Particle counts were obtained using a condensation particle counter (model 3022A; TSA, Shoreview, MN) and mass concentration of particles was calculated using idealized particle density of 1.5g/cm3. Exposure chambers were maintained at 77–79°F with relative humidity of 35–40%.

Starting on PND60, mice received secondary challenge with PQ+MB. Animals received 10 mg/kg PQ (Sigma) + 30 mg/kg MB (Chem Services) or saline vehicle in intraperitoneal injection administered twice per week for 6 weeks for a total of 12 injections. This generated 4 experimental treatment groups: Air/Saline, Air/PQ+MB, CAPS/Saline, or CAPS/PQ+MB.

Approximately 2 weeks after final PQ+MB injection, animals were euthanized. In mice receiving PQ+MB, the five animals the lowest levels of horizontal locomotor movement were selected for stereology. In those receiving saline vehicle, mice were chosen randomly for stereology. Animals were sedated using sodium pentobarbital and underwent transcardiac perfusion with phosphate buffered saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Once fixed, brains were removed from the cranium and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, followed by cryo-protection in 30% sucrose for an additional 24 hours. The remaining animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation without sedation to preclude effects of anesthetic on central neurochemistry.

2.2 Locomotor behavior

Locomotor behavior was measured in response to PQ+MB injection immediately and 24 hours following injection starting after the 7th injection of PQ+MB in photobeam chambers equipped with a transparent acrylic arena with a 48-channel infrared source detector and controller (Med-Associates). Activity was quantified in 45 minute sessions occurring once per day immediately after vehicle (saline) or PQ+MB injection. All mice were injected with saline on days they did not receive PQ+MB. Ambulatory counts were defined as the number of beam breaks while in ambulatory movement. Vertical was defined as total time spent breaking any photobeam in the Z-axis. Jump time was amount of time spent with no photobeam breaks in the XY axis, and horizontal counts were defined as the number of beam breaks in a 2 by 2 photobeam box that were non-ambulatory (i.e. remained within the 2 × 2 photobeam box).

2.3 TH-positive Cell Counts in the SNpc and TH expression in the Striatum

Fixed and cryo-protected brains were sectioned at 30 µm on a freezing microtome into a series of 6 wells. Every 6th section was immunolabeled for tyrosine hydroxylase and counterstained using cresyl violet to identify nissl-positive nuclei. Briefly, free floating sections were washed in 0.1M tris-buffered saline (pH 7.4; TBS), endogenous peroxidases were deactivated by incubation in 10% methanol/3% hydrogen peroxide in 0.1M TBS for 10 minutes, tissue was blocked in 5% normal goat serum for 1 hour, followed by incubation in primary TH antibody (1:4000 dilution; Millipore, AB152) Tissue was then incubated in goat anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody (BA1000, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature followed by incubation in avidin-biotin solution (PK6100, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) followed by visualization using 3-3’-diaminobenzidine. After being mounted on VWR superfrost plus slides, brain sections were counterstained with cresyl violet. TH-positive cells and nissl bodies were stereologically estimated using the optical fractionator method in MBF Stereoinvestigator (Barlow et al. 2004). TH-positive neurons and nissl-positive bodies in the substantia nigra pars compacta of every 6th brain section were counted. Relative expression of striatal TH was assessed using densitometry in ImageJ and is reported as percent control.

2.4 Neurotransmitter Quantification by HPLC

Levels of monoamines were quantified in the frontal cortex, midbrain (containing substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area), and striatum (combined dorsal and ventral), and levels of glutamate, glutamine, and GABA were quantified in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, frontal cortex, striatum, midbrain, and olfactory bulb. Dopamine (DA), dihydroxylphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), homovanillic acid (HVA), norepinephrine (NE), serotonin (5-HT), and 5-hydroxylindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) were analyzed using HPLC coupled with an electrochemical detector as previously described (Cory-Slechta et al. 2013). Levels of glutamine, glutamate, and GABA were determined using HPLC coupled with a fluorescence detector in a method previously described (Cory-Slechta et al. 2013). Concentrations of neurotransmitters were expressed as ng or µg per mg protein. Total brain region protein was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay. DA turnover (DA TO) was calculated as the ratio of [DOPAC]/[DA].

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Two-factor repeated measures ANOVAs were used to analyze locomotor activity data with CAPS exposure and PQ+MB as between factors and session as a within factor. Fisher’s protected least squares differences (PLSDs) were used for post-hoc analysis when appropriate. Two-factor ANOVAs (CAPS exposure and PQ+MB) were used to analyze neurochemistry, stereological cell counts in the SNpc, and TH densitometry in the striatum. Two-sided p-values were used to determine statistical significance for changes in neurotransmitters and locomotor behavior, whereas one-sided p-values were used for stereological cell counts and TH densitometry given the a priori one-sided hypothesis of decreased cell counts and expression of TH (McCormack et al. 2002; Purisai et al. 2007; Thiruchelvam et al. 2003a). Forward stepwise regression was used to build statistical models examining the ability of changes in brain neurochemistry to predict horizontal count, with probability to leave and enter the model set to 0.25.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Exposure

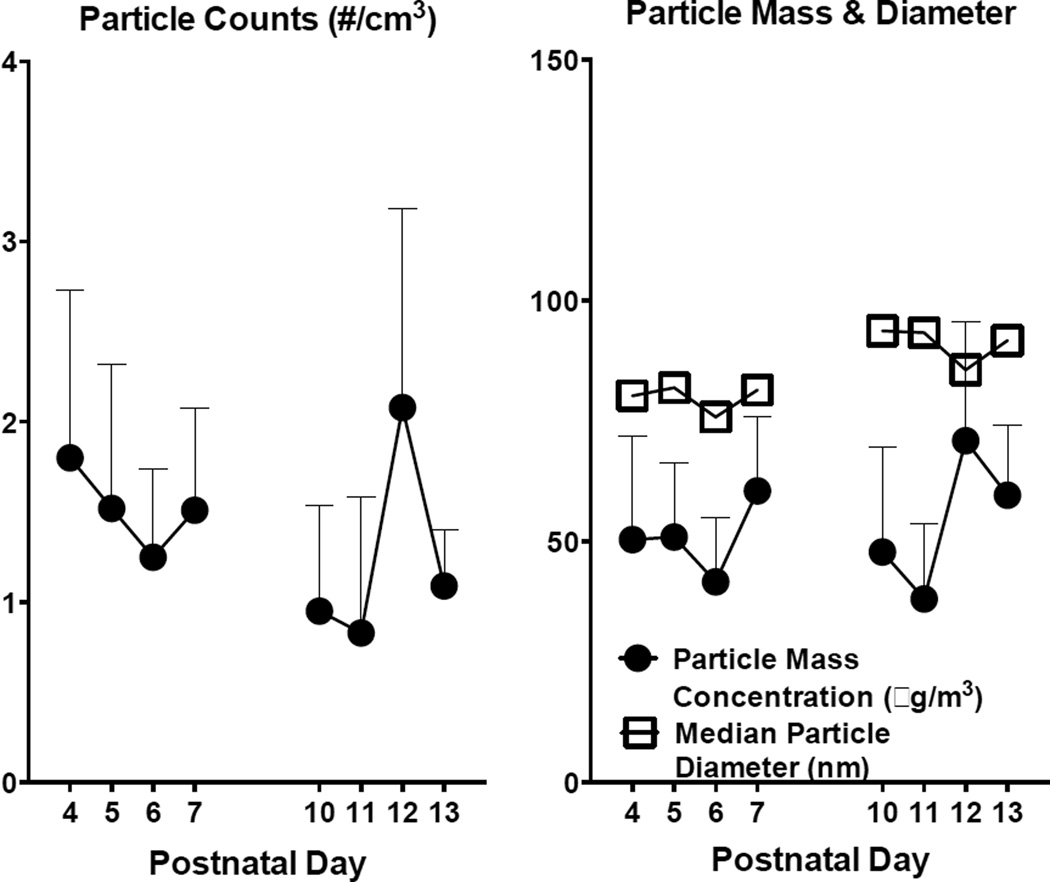

Average particle counts (mean ± SD) in the exposure chambers during postnatal exposures averaged 138,000 ± 43,000 particles/cm3, which corresponded to mass concentration of 53 µg/m3 ± 10.7 (mean ± SD). Particle sizes remained less than 100 nm over all exposure days (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean particle counts (left) and particle mass concentration (right) ± SD for each day of exposure. Mean particle diameter (right) ± SD for each day of exposure.

3.2 Locomotor behavior

3.2.1 Activity Immediately Following Injection with PQ+MB or Vehicle

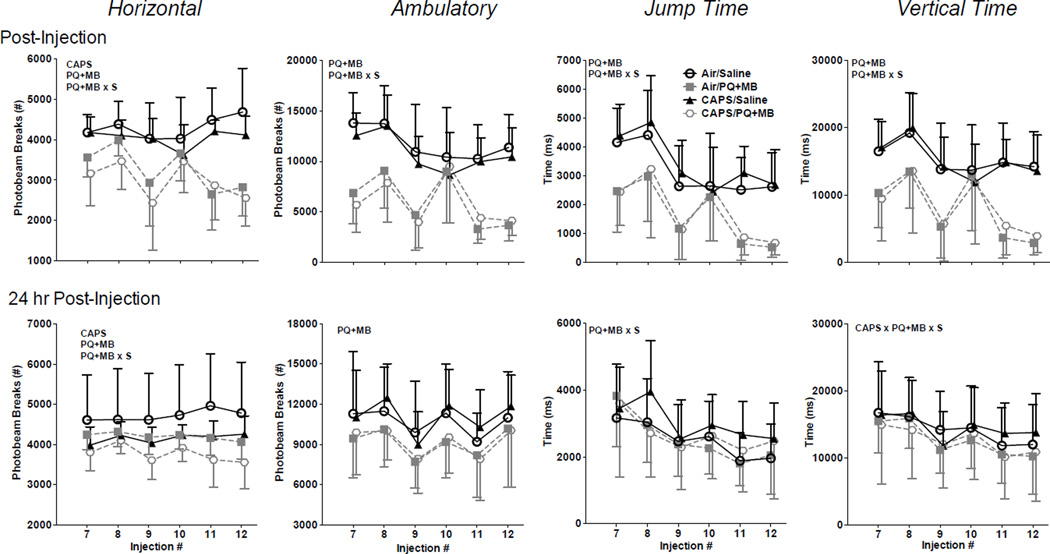

Immediately following injection of PQ+MB or saline vehicle, CAPS-treated animals exhibited reductions in horizontal activity as compared air-treated controls (main effect of CAPS: F(1,55)=5.1646, p=0.027). PQ +MB also reduced horizontal activity of mice (main effect of PQ+MB: F(1,55)=78.77, p<0.0001). However, no statistical interaction of CAPS by PQ+MB was observed (Figure 2, top row). PQ+MB treated animals also exhibited reductions in ambulatory activity, jump time, and vertical time (main effect of PQ+MB F(1,55)=87.87, p<0.0001, F(1,55)=53.01, p<0.0001, & F(1,55)=55.57, p<0.0001, respectively), with no effect of CAPS, nor any statistical interactions of CAPS by PQ+MB. The magnitude of PQ+MB-induced reductions in horizontal, ambulatory, jump, and vertical activity generally increased across sessions as confirmed by significant interactions of PQ+MB by Session (F(5,51)=13.25, p<0.0001; F(5,51)= 5.97, p<0.001; F(5,51)=3.59, p<0.01; F(5,51)=7.46, p<0.0001). Specifically, reductions in horizontal activity of approximately 24% were seen in session 7 had further declined to 45% at session 12. Correspondingly, initial reductions in ambulatory counts were 59% and further declined to 68%. Even greater decrements in rearing-related measures were seen, with initial reductions of 41% in jump time that had further increased to 80% by session 12, and initial reductions of 43% in vertical time that had increased to 80% by session 12.

Figure 2.

Horizontal counts, ambulatory counts, jump time, and vertical time of mice treated with Air/Saline, Air/PQ+MB, CAPS/Saline, & CAPS/PQ+MB immediately following PQ+MB injection (top row) and again 24 hours post-injection (bottom row) as measured over the last 6 injections (of a total of 12). PQ+MB indicates main effect of PQ+MB, CAPS indicates main effect of CAPS, and S represents interaction with session. Data reported as Mean ± SE. (n=14=15/treatment group).

3.2.2 Activity 24-hours following injection with PQ+MB or Vehicle

Significant reductions in horizontal activity were still present 24 hours following injection of PQ+MB (main effect PQ+MB: F(1,55)=8.03, p<0.01) (Figure 2, bottom row). CAPS-treated animals also continued to sustain reduced locomotor activity (main effect of CAPS: F(1,55)=9.75, p<0.01), with combined exposure to CAPS and PQ+MB producing the lowest locomotor activity levels. Although no statistically significant interaction was detected, it was notable that the reductions as measured at session 12 appeared to be additive for the CAPS/PQ+MB mice, at 26%, while reductions for CAPS alone were 11% and those for PQ+MB alone were 15%. Ambulatory activity levels likewise remained lower in PQ+MB-treated mice (main effect PQ+MB: F(1,55)=6.38, p<0.05). For jump time, a significant interaction of PQ+MB by Session was observed (F(5,275)=2.90, p<0.05), while no systematic treatment-related differences in vertical activity were observed 24 hours following PQ+MB injection.

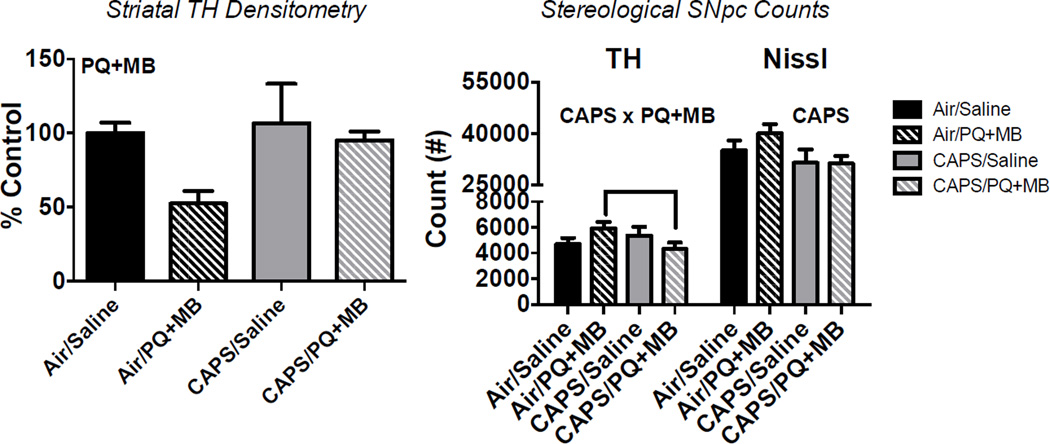

3.3. SNpc TH-Positive Cell Counts and Striatal TH Expression

Tyrosine hydroxylase expression in the striatum was reduced by PQ+MB treatment (main effect PQ+MB: F(1,1)=4.07, p<0.05), with Air/PQ+MB animals having approximately 50% of the TH-expression in striatum of that of Air/Saline controls, and CAPS/PQ+MB animals having approximately 95% of that of Air/Saline control (Figure 3, left). CAPS exposure significantly reduced nissl body counts in the SNpc by approximately 10% (main effect of CAPS: F(1,1)=4.54, p<0.05). TH-positive cells in the SNpc were 27% lower in CAPS/PQ+MB mice compared to Air/PQ+MB animals and 8% lower than those of Air/Saline controls (CAPS × PQ+MB Interaction: F(3,15)=2.10, p<0.05; post hoc p<0.05)..

Figure 3.

Density of TH in the striatum (left) and stereological cell counts of TH+ neurons and nissl positive bodies in the SNpc (right) of mice exposed to Air/Saline, Air/PQ+MB, CAPS/Air, and CAPS/PQ+MB. Data reported as mean ± SE. PQ+MB indicates main effect of PQ+MB, CAPS indicates main effect of CAPS, and CAP × PQ+MB represents statistical interaction between the two treatments. (n=4–5/treatment group).

3.4. Monoamine Neurotransmitters in Striatum, Midbrain, and Cortex

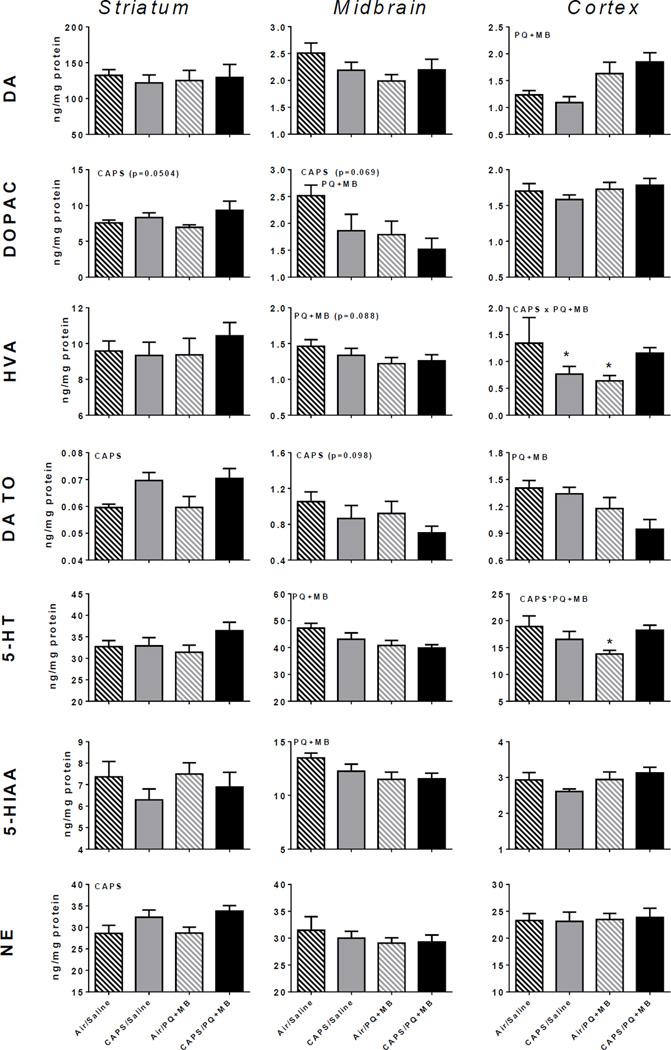

3.4.1 Striatum

Levels of DOPAC, DA TO, and NE in the striatum were significantly increased by CAPS exposure (main effect CAPS on DOPAC: F(3,35)=4.10, p=0.05; DA TO: F(3,35)=10.15, p<0.01; on NE: F(3,35)=8.07, p<0.01), but no changes in DA were observed (Figure 4, left column). Further, no changes in serotonin or its metabolite 5-HIAA were found.

Figure 4.

Monoamine neurotransmitters and metabolites in mice exposed to Air/Saline, Air/PQ+MB, CAPS/Saline, and CAPS/PQ+MB in striatum (left column), midbrain (middle column) and cortex (right column). Data reported as group mean ± SE. DA TO calculated as [DOPAC]/[DA]. Reported in ng neurotransmitter or metabolite/mg protein. CAPS or PQ+MB indicates main effect of CAPS or PQ+MB, respectively. CAPS × PQ+MB indicates statistical interaction of the treatments. * denotes statistical significance from Air/Saline. (n=9–10/treatment group).

3.4.2 Midbrain

CAPS exposure resulted in trends of decreased DA TO and DOPAC in midbrain (main effect of CAPS on DA TO: F(3,35)=2.89, p=0.098; on DOPAC: F(3,35)=3.52, p=0.069), while PQ+MB significantly reduced levels of HVA (15%; main effect of PQ+MB: F(3,35)=3.10, p=0.088) (Figure 4, middle column). PQ+MB also significantly reduced midbrain DOPAC (40%; main effect of PQ+MB: F(3,35)=4.70, p<0.05) and 5-HT (16%; main effect of PQ+MB: F(3,35)=6.67, p<0.05).

3.4.3 Frontal Cortex

As compared to Air/Air animals, HVA levels were decreased (Figure 4, right column) in CAPS/Saline and Air/PQ+MB mice (43–52%; interaction of CAPS by PQ+MB: F(3,31)=5.10, p<0.05; post hocs p<0.05), and 5-HT was reduced 27% in CAPS/Saline, mice (interaction of CAPS by PQ+MB: F(3,35)=6.45. p<0.05). PQ+MB increased cortical DA (50%; main effect of PQ+MB F(3,35)=13.86, p<0.001) and reduced DA TO (33%; main effect of PQ+MB: F(3,35)=9.50, p<0.01).

3.5 Striatal, Midbrain, Cortical, Olfactory Bulb, and Hypothalamic Amino Acid Levels

3.5.1. Striatum

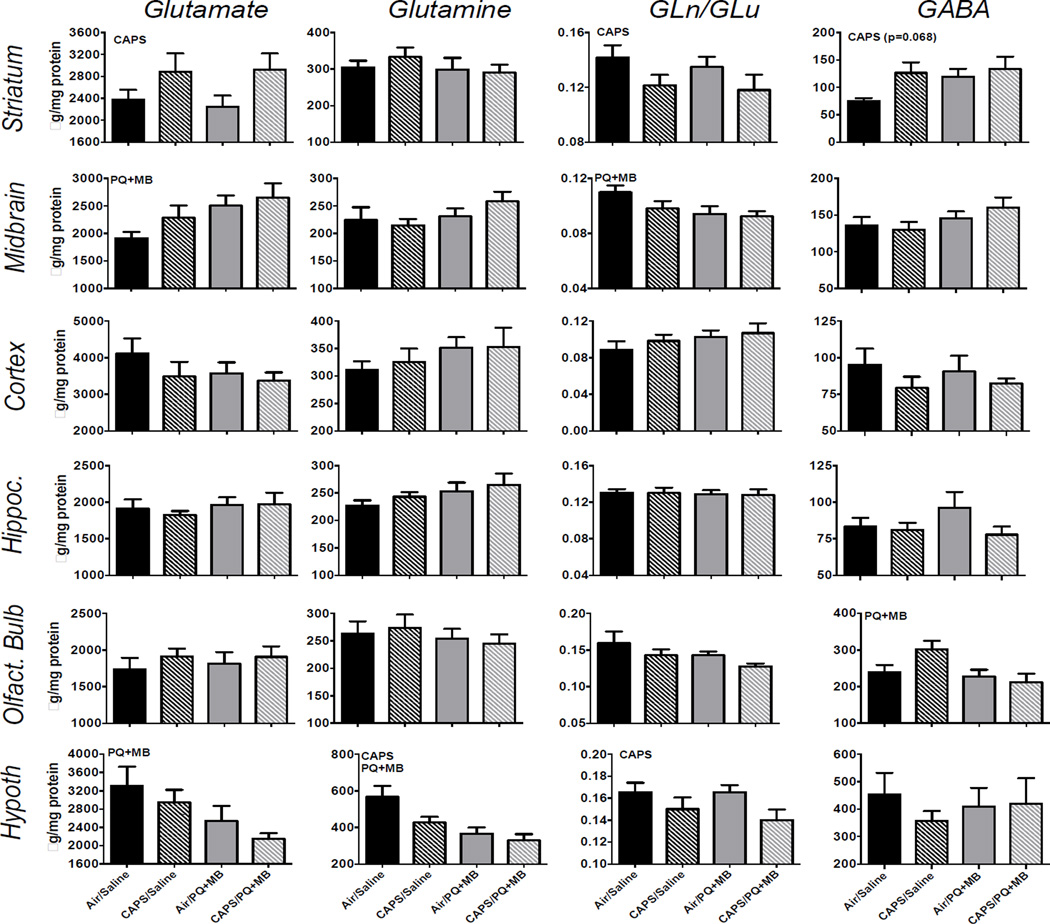

Striatal glutamate was significantly increased 23% by CAPS exposure (main effect of CAPS: F(3,35)=4.98, p<0.05), with similar trends observed for striatal GABA (F(3,35)=3.56, p=0.068) (Figure 5, top row), while A CAPS-induced reduction in the ratio of striatal glutamine/glutamate was also observed (17%; main effect of CAPS: F(3,35)=4.29, p<0.05).

Figure 5.

Amino acid neurotransmitter levels in indicated brain regions in mice exposed to Air/Saline, Air/PQ+MB, CAPS/Saline, and CAPS/PQ+MB. Data reported as group mean ± SE. DA TO calculated as [DOPAC]/[DA]. Reported in ng neurotransmitter or metabolite/mg protein. CAPS or PQ+MB indicates main effect of CAPS or PQ+MB, respectively. CAPS × PQ+MB indicates statistical interaction of the treatments. * denotes statistical significance from Air/Saline. (n=9–10/treatment group).

3.5.2. Midbrain

PQ+MB increased midbrain glutamate levels by 39% (Figure 5, second row; main effect of PQ+MB: F(3,35)= 5.39, p<0.05) and decreased the ratio of glutamine/glutamate by 16% (main effect of PQ+MB: F(3,35)=4.60, p<0.05).

3.5.3. Frontal Cortex

No treatment-related changes in amino acid neurotransmitters were observed in the cortex.

3.5.4 Olfactory Bulb

PQ+MB decreased GABA in olfactory bulb by 13% (Figure 5, 4th row; main effect of PQ+MB: F(3,35)= 5.08, p<0.05).

3.5.5. Hypothalamus

CAPS decreased hypothalamic glutamine by 42% (main effect of CAPS: F(3,35)=4.96, p<0.05) and glutamine/glutamate ratio by 15% (Figure 5, bottom row; main effect of CAPS: F(3,35)=5.22, p<0.05). An effect of PQ+MB, without modification by CAPS exposure, was also found for glutamine and glutamate levels, such that each was reduced (42% and 35%, respectively; main effect of PQ+MB on glutamine: F(3,35)=13.92, P<0.001; on glutamate: F(3,35)= 6.88, p<0.05).

4.1 DISCUSSION

This study sought to determine whether CAPS exposure during early postnatal brain development altered the response to neurotoxic challenge with PQ+MB, a model of the PDP phenotype (Thiruchelvam et al. 2000a; Thiruchelvam et al. 2003b). To this end, mice were exposed to average daily CAPS levels of 138,000±43,000 particles/cm3 which corresponded to 53 ± 10 µg/m3 (Figure 1). These concentrations of particles are environmentally relevant to humans, as particle concentrations in Los Angeles, California, USA and Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA have been reported at 200,000–400,000 particles/cm3 with peak episodic counts reaching as high as 2,000,000 particles/cm3 in Minneapolis (Kittelson 2004; Westerdahl et al. 2005). Particles remained less than 100nm (i.e., ultrafine) over all exposure days (Figure 1). The real-world nature of this exposure paradigm and the natural variability in UFP in, outdoor air is the source of day-to-day variability in exposure metrics.

Indeed, animals treated with CAPS in the early postnatal period show enhanced response to PDP-inducing pesticides PQ+MB. Some limited evidence that CAPS enhanced the PQ+MB-induced PDP phenotype was observed. For example, while CAPS alone reduced horizontal activity, when combined with PQ+MB in adulthood (CAPS/PQ+MB) it resulted in an attenuated recovery of horizontal locomotor activity 24 hr post dosing as did mice treated with PQ+MB alone (Figure 2), although this did not result in a significant statistical interaction of PQ+MB by CAPS. Consistent with previous reports in young adult mice indicating that increasing age is associated with increased susceptibility to PQ+MB (Thiruchelvam et al. 2003b), significant PQ+MB-induced reductions in SNpc dopaminergic cell counts (Figure 3) were not seen. Indeed, there was a slight, but not statistically significant, increase in dopaminergic cell counts in the SNpc of Air/PQ+MB compared to Air/Saline. However, CAPS/PQ+MB animals had significantly reduced dopaminergic cell counts in the SNpc compared to Air/PQ+MB (Figure 3). Expression of striatal TH was reduced by PQ+MB, but that reduction was actually less severe (although not statistically) in animals receiving CAPS treatment in the early postnatal period (Figure 3). In addition, CAPS alone induced a significant 16.5% reduction of nissl positive cell nuclei in the SNpc that were not positive for tyrosine hydroxylase (Figure 3). TH-immunolabeling was used to identify TH-positive cells in the SNpc with cresyl violet counterstaining to identify nisslpositive nuclei in the same brain region. Although unbiased stereology is considered to be the gold standard for such estimations, the possibility remains that CAPS or PQ+MB may have altered TH-expression, as demonstrated in models using MPTP (Kastner et al. 1994) and traumatic brain injury (Yan et al. 2007) and/or TH epitope availability which would have carried over into stereological estimations. Given that reductions in dopaminergic cells in the SNpc were not observed in this study (figure 3), we did not expect to find reductions in striatal dopamine, and indeed no interactive effects of CAPS/PQ+MB were observed (Figure 4) for monoamines in striatum, midbrain or cortex that would indicate more enhanced effects of the combination.

Instead, neurotransmitter changes in particular suggest different targets for CAPS relative to PQ+MB in brain dopamine systems (Figures 4–5). Specifically, PQ+MB appeared to primarily target midbrain monoamine and amino acid function, decreasing levels of midbrain DOPAC (marginally) and DA turnover, serotonin and its metabolite 5-HIAA. In addition, PQ+MB increased levels of midbrain glutamate and reduced a measure of glutamate turnover (glutamine/glutamate). In contrast, CAPS appeared to target striatal monoamines and amino acids, where it increased levels of DOPAC and DA turnover as well as increasing NE; CAPS, like PQ+MB, also increased striatal glutamate and GABA (marginally) levels while reducing glutamate turnover. Collectively, except for glutamate turnover, CAPS and PQ+MB appeared to produce opposite effects in these two regions of the nigrostriatal system which may ultimately result in the limited CAPS/PQ+MB interactions as related to locomotor activity in particular.

Glutamate and GABA play significant roles in basal ganglia neurocircuitry that encompasses the nigrostriatal dopamine tract and is critical to motor control (reviewed in Hikosaka (2007) and (Hauber 1998). As noted, while both CAPS and PQ+MB increased glutamate and reduced glutamate turnover, they did so in a region-dependent manner, with CAPS effects primarily in striatum and PQ+MB in midbrain. Interestingly the increases in glutamate may indicate an ongoing excitotoxic mechanism affecting both ends of the nigrostriatal dopamine tract, i.e., the cell bodies (midbrain) and terminal projection region (striatum). Interestingly, glutamate excitotoxicity has been posited to serve as a mechanism for the progression of DA cell neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Further, striatal perfusion by glutamate was followed by increased levels of DA in striatum (Morales et al. 2013), consistent with findings here for CAPS. Further, in the hypothalamus, which includes the subthalamic nucleus, a brain region important in basal ganglia motor neurocircuitry (Groenewegen et al. 1993), PQ+MB reduced glutamate and glutamine, and CAPS reduced glutamine and glutamine/glutamate ratio (Figure 5) and glutamatergic pathways linking hypothalamus to subthalamic nuclei have been shown to play a role in running behavior originating in hypothalamus (Narita et al. 1993; Narita et al. 2002).

Providing that PQ+MB does not induce a significant change in dopaminergic cell counts in the SNpc and CAPS/PQ+MB animals have only a 5% reduction in striatal TH expression whereas Air/PQ+MB animals have an approximately 50% reduction (figure 3), it appears that a neurochemical mechanism is most likely to explain the enhanced susceptibility of CAPS pretreated animals to the horizontal activity reducing effects of PQ+MB that results in less recovery. Forward stepwise linear regressions by group were used to build models to predict the horizontal activity on the recovery day using both monoamine and amino acid neurochemistry. The significant models and relevant statistics stemming from such regressions are reported in Table 1. Interestingly, striatal GABA, which was marginally increased in CAPS-exposed animals (Figure 5), which is consistent with observations in post-mortem human striatum (Emir et al. 2012; Kish et al. 1986) and animal models of nigrostriatal lesions (Tanaka et al. 1986), was only selected for the model generated for CAPS/PQ+MB-treated mice (Table 1). GABA has an important and central role in the basal ganglia neurocircuitry with GABA-based efferents from the Globus pallidus internus (GPi) and the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) to areas including the thalamus & cerebral cortex outside the basal ganglia. The striatum is comprised of dopaminergic neurons, cholinergic neurons, and GABAergic interneurons and output neurons (Betarbet et al. 1997; Galvan and Wichmann 2007; Kawaguchi et al. 1995). The GABAergic output neurons feed to the GPi/SNr in the so-called direct pathway, whereas the indirect pathway involves the Globus pallidus externus (GPe) and the subthalamic nucleus (Smith et al. 1998). Downstream effects of increased GABA in the striatum would be hypothesized to include motor dysfunction and may explain the decreased ability to recovery from PQ+MB in animals pre-treated with CAPS in the early postnatal period (Figure 2). Moreover, CAPS/PQ+MB mice also showed the lowest levels of hypothalamic glutamate, glutamine and glutamate turnover; hypothalamic glutamate was found in models for both Air/Saline and CAPS/Saline, but was no longer significant in the case of PQ+MB, either for Air/PQ+MB or CAPS/PQ+MB.

Table 1.

Results of forward stepwise linear regression analysis used to model horizontal activity collected 24 hours after PQ+MB administration for each model. (n=9–10 animals/treatment group).

| Air/Saline: (r2=1): | Air/PQ+MB (r2=0.73): | CAPS/Saline (r2=1): | CAPS/PQ+MB (r2=0.76): |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothalamic Glutamate | Cortical 5-HT | Hypothalamic Glutamate | Striatal GABA |

| Striatal Glutamate | Striatal Gln/Glu | Cortical DA TO | |

| Cortical DA | Cortical DA | Midbrain DA TO | |

| Midbrain DOPAC | Cortical HVA | ||

| Midbrain DA TO | Midbrain HVA | ||

| Striatal DA TO | Cortical DA TO |

Taken together these data indicate that mice treated with CAPS in the early postnatal period show some evidence of an enhanced response to neurotoxic challenge with two pesticides known to induce components of the PDP, namely PQ+MB (Figures 2, 4, & 5), particularly as a trend towards a delayed recovery of horizontal locomotor activity reductions measured 24 hr post PQ+MB that may be related to corresponding changes in striatal GABA and/or hypothalamic amino acids. Notably, however, CAPS and PQ+MB targeted different regions of the nigrostriatal tract, with PQ+MB affecting midbrain, site of DA neuronal cell bodies, while CAPS appears to target the terminal projection region (striatum) of the nigrostriatal DA system, the latter findings demonstrating the capacity of early postnatal exposure to CAPS to produce sustained neurochemical alterations in adulthood. Future studies should include administration of PQ+MB during late adulthood or in later age or co-administration of PQ+MB with ultrafine CAPS (<100nm) in the early postnatal period, as these have been indicated to produce greater nigrostriatal dopaminergic neuron degeneration and more severe PDP.

Highlights.

CAPS enhanced motor activity reduction measured 24 hrs after PQ+MB injection

PQ+MB affected DA neuronal cell bodies while CAPS affected projection region

CAPS impacted striatal dopamine-glutamate function

PQ+MB impacted midbrain dopamine-glutamate function

CAPS and PQ+MB elevate glutamate in striatum and midbrain, respectively

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported in part by R21 ES 019105 (D. Cory-Slechta, PI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Joshua L Allen, Email: joshua_allen@urmc.rochester.edu.

Xiufang Liu, Email: suexfliu@hotmail.com.

Douglas Weston, Email: douglas_weston@urmc.rochester.edu.

Katherine Conrad, Email: Katherine_bachmann@urmc.rochester.edu.

Günter Oberdörster, Email: gunter_oberdorster@urmc.rochester.edu.

Deborah A Cory-Slechta, Email: deborah_cory-slechta@urmc.rochester.edu.

REFERENCES

- Bandeira F, Lent R, Herculano-Houzel S. Changing numbers of neuronal and non-neuronal cells underlie postnatal brain growth in the rat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:14108–14113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804650106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow BK, Richfield EK, Cory-Slechta DA, Thiruchelvam M. A fetal risk factor for parkinson's disease. Developmental neuroscience. 2004;26:11–23. doi: 10.1159/000080707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarbet R, Turner R, Chockkan V, DeLong MR, Allers KA, Walters J, et al. Dopaminergic neurons intrinsic to the primate striatum. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6761–6768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06761.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge CB, Sturgess NC, Butt M, Wolf JC, Zadory D, Beck M, et al. Pharmacokinetic, neurochemical, stereological and neuropathological studies on the potential effects of paraquat in the substantia nigra pars compacta and striatum of male c57bl/6j mice. Neurotoxicology. 2013;37:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Fan LW, Kaizaki A, Tien LT, Ma T, Pang Y, et al. Neonatal systemic exposure to lipopolysaccharide enhances susceptibility of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons to rotenone neurotoxicity in later life. Developmental neuroscience. 2013;35:155–171. doi: 10.1159/000346156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A, Oldham M, Becaria A, Bondy SC, Meacher D, Sioutas C, et al. Particulate matter in polluted air may increase biomarkers of inflammation in mouse brain. Neurotoxicology. 2005;26:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A, Araujo JA, Li H, Sioutas C, Kleinman M. Particulate matter induced enhancement of inflammatory markers in the brains of apolipoprotein e knockout mice. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2009;9:5099–5104. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2009.gr07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory-Slechta DA, Thiruchelvam M, Barlow BK, Richfield EK. Developmental pesticide models of the parkinson disease phenotype. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1263–1270. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory-Slechta DA, Weston D, Liu S, Allen JL. Brain hemispheric differences in the neurochemical effects of lead, prenatal stress, and the combination and their amelioration by behavioral experience. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2013;132:419–430. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello S, Cockburn M, Bronstein J, Zhang X, Ritz B. Parkinson's disease and residential exposure to maneb and paraquat from agricultural applications in the central valley of california. American journal of epidemiology. 2009;169:919–926. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emir UE, Tuite PJ, Oz G. Elevated pontine and putamenal gaba levels in mild-moderate parkinson disease detected by 7 tesla proton mrs. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan LW, Tien LT, Lin RC, Simpson KL, Rhodes PG, Cai Z. Neonatal exposure to lipopolysaccharide enhances vulnerability of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons to rotenone neurotoxicity in later life. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;44:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein MM, Jerrett M. A study of the relationships between parkinson's disease and markers of traffic-derived and environmental manganese air pollution in two canadian cities. Environ Res. 2007;104:420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A, Wichmann T. Gabaergic circuits in the basal ganglia and movement disorders. Progress in brain research. 2007;160:287–312. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)60017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlofs-Nijland ME, van Berlo D, Cassee FR, Schins RP, Wang K, Campbell A. Effect of prolonged exposure to diesel engine exhaust on proinflammatory markers in different regions of the rat brain. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen HJ, Berendse HW, Haber SN. Organization of the output of the ventral striatopallidal system in the rat: Ventral pallidal efferents. Neuroscience. 1993;57:113–142. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90115-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra R, Vera-Aguilar E, Uribe-Ramirez M, Gookin G, Camacho J, Osornio-Vargas AR, et al. Exposure to inhaled particulate matter activates early markers of oxidative stress, inflammation and unfolded protein response in rat striatum. Toxicol Lett. 2013;222:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaxma CA, Bloem BR, Borm GF, Oyen WJ, Leenders KL, Eshuis S, et al. Gender differences in parkinson's disease. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2007;78:819–824. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.103788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauber W. Involvement of basal ganglia transmitter systems in movement initiation. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56:507–540. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O. Gabaergic output of the basal ganglia. Progress in brain research. 2007;160:209–226. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)60012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastner A, Herrero MT, Hirsch EC, Guillen J, Luquin MR, Javoy-Agid F, et al. Decreased tyrosine hydroxylase content in the dopaminergic neurons of mptp-intoxicated monkeys: Effect of levodopa and gm1 ganglioside therapy. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:206–214. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Wilson CJ, Augood SJ, Emson PC. Striatal interneurones: Chemical, physiological and morphological characterization. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:527–535. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)98374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kish SJ, Rajput A, Gilbert J, Rozdilsky B, Chang LJ, Shannak K, et al. Elevated gamma-aminobutyric acid level in striatal but not extrastriatal brain regions in parkinson's disease: Correlation with striatal dopamine loss. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:26–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittelson DB. Nanoparticle emissions on minnesota highways. Atmos Environ. 2004;38:9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lee PC, Bordelon Y, Bronstein J, Ritz B. Traumatic brain injury, paraquat exposure, and their relationship to parkinson disease. Neurology. 2012;79:2061–2066. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182749f28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque S, Surace MJ, McDonald J, Block ML. Air pollution & the brain: Subchronic diesel exhaust exposure causes neuroinflammation and elevates early markers of neurodegenerative disease. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2011a;8:105. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque S, Taetzsch T, Lull ME, Kodavanti U, Stadler K, Wagner A, et al. Diesel exhaust activates and primes microglia: Air pollution, neuroinflammation, and regulation of dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 2011b;119:1149–1155. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque S, Taetzsch T, Lull ME, Johnson JA, McGraw C, Block ML. The role of mac1 in diesel exhaust particle-induced microglial activation and loss of dopaminergic neuron function. J Neurochem. 2013;125:756–765. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack AL, Thiruchelvam M, Manning-Bog AB, Thiffault C, Langston JW, Cory-Slechta DA, et al. Environmental risk factors and parkinson's disease: Selective degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons caused by the herbicide paraquat. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:119–127. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin DR, Apelberg BJ, Roe S, Divita F., Jr Livestock ammonia management and particulate-related health benefits. Environmental science & technology. 2002;36:1141–1146. doi: 10.1021/es010705g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales I, Sabate M, Rodriguez M. Striatal glutamate induces retrograde excitotoxicity and neuronal degeneration of intralaminar thalamic nuclei: Their potential relevance for parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38:2172–2182. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita K, Yokawa T, Nishihara M, Takahashi M. Interaction between excitatory and inhibitory amino acids in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus in inducing hyper-running. Brain research. 1993;603:243–247. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91243-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita K, Murata T, Honda K, Nishihara M, Takahashi M, Higuchi T. Subthalamic locomotor region is involved in running activity originating in the rat ventromedial hypothalamus. Behavioural brain research. 2002;134:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberdorster G. Toxicology of ultrafine particles: In vivo studies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A. 2000;358:2719–2740. [Google Scholar]

- Priyadarshi A, Khuder SA, Schaub EA, Priyadarshi SS. Environmental risk factors and parkinson's disease: A metaanalysis. Environ Res. 2001;86:122–127. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purisai MG, McCormack AL, Cumine S, Li J, Isla MZ, Di Monte DA. Microglial activation as a priming event leading to paraquat-induced dopaminergic cell degeneration. Neurobiology of disease. 2007;25:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajput AH, Uitti RJ, Stern W, Laverty W, O'Donnell K, O'Donnell D, et al. Geography, drinking water chemistry, pesticides and herbicides and the etiology of parkinson's disease. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 1987;14:414–418. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100037823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y, Bevan MD, Shink E, Bolam JP. Microcircuitry of the direct and indirect pathways of the basal ganglia. Neuroscience. 1998;86:353–387. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Niijima K, Mizuno Y, Yoshida M. Changes in gamma-aminobutyrate, glutamate, aspartate, glycine, and taurine contents in the striatum after unilateral nigrostriatal lesions in rats. Exp Neurol. 1986;91:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(86)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner CM, Chen B, Wang WZ, Peng ML, Liu ZL, Liang XL, et al. Environmental factors in the etiology of parkinson's disease. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 1987;14:419–423. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100037835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiruchelvam M, Richfield EK, Baggs RB, Tank AW, Cory-Slechta DA. The nigrostriatal dopaminergic system as a preferential target of repeated exposures to combined paraquat and maneb: Implications for parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2000a;20:9207–9214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09207.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiruchelvam M, Richfield EK, Baggs RB, Tank AW, Cory-Slechta DA. The nigrostriatal dopaminergic system as a preferential target of repeated exposures to combined paraquat and maneb: Implications for parkinson's disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000b;20:9207–9214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09207.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiruchelvam M, McCormack A, Richfield EK, Baggs RB, Tank AW, Di Monte DA, et al. Age-related irreversible progressive nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurotoxicity in the paraquat and maneb model of the parkinson's disease phenotype. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2003a;18:589–600. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiruchelvam M, McCormack A, Richfield EK, Baggs RB, Tank AW, Di Monte DA, et al. Age-related irreversible progressive nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurotoxicity in the paraquat and maneb model of the parkinson's disease phenotype. Eur J Neurosci. 2003b;18:589–600. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tien LT, Kaizaki A, Pang Y, Cai Z, Bhatt AJ, Fan LW. Neonatal exposure to lipopolysaccharide enhances accumulation of alpha-synuclein aggregation and dopamine transporter protein expression in the substantia nigra in responses to rotenone challenge in later life. Toxicology. 2013;308:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A, Costello S, Cockburn M, Zhang X, Bronstein J, Ritz B. Parkinson's disease risk from ambient exposure to pesticides. European journal of epidemiology. 2011;26:547–555. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9574-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerdahl D, Fruin S, Sax T, Fine PM, Sioutas C. Mobile platform measurments of ultrafine particles and associated pollutant concentrations on freeways and residential stresses in los angeles. Atomospheric Environment. 2005;39:3597–3610. [Google Scholar]

- Wooten GF, Currie LJ, Bovbjerg VE, Lee JK, Patrie J. Are men at greater risk for parkinson's disease than women? Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2004;75:637–639. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.020982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan HQ, Ma X, Chen X, Li Y, Shao L, Dixon CE. Delayed increase of tyrosine hydroxylase expression in rat nigrostriatal system after traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2007;1134:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]