Abstract

Young people tend to disclose relationship violence experiences to their peers, if they disclose at all, yet little is known about the nature and frequency of adolescent help-seeking and help-giving behaviors. Conducted within a sample of 1,312 young people from four New York City high schools, this is the first paper to ask adolescent help-givers about the various forms of help they provide and among the first to examine how ethnicity and nativity impact help-seeking behaviors. Relationship violence victims who had ever disclosed (61 %) were more likely to choose their friends for informal support. Ethnicity was predictive of adolescent disclosure outlets, whereas gender and nativity were not. Latinos were significantly less likely than non-Latinos to ever disclose to only friends, as compared to disclosing to at least one adult. The likelihood of a young person giving help to their friend in a violent relationship is associated with gender, ethnicity, and nativity, with males being significantly less likely than females to give all forms of help to their friends (talking to their friends about the violence, suggesting options, and taking action). Foreign-born adolescents are less likely to talk or suggest options to friends in violent relationships. This study also found that Latinos were significantly more likely than non-Latinos to report taking action with or on behalf of a friend in a violent relationship. This research shows that adolescents often rely on each other to address relationship violence, underlining the importance of adolescents’ receipt of training and education on how to support their friends, including when to seek help from more formal services. To further understand the valuable role played by adolescent peers of victims, future research should explore both which forms of help are perceived by the victim to be most helpful and which are associated with more positive outcomes.

Keywords: Dating violence, Relationship violence, Help-giving, Help-seeking, Adolescents, Peer support

Adolescent relationship violence—sexual, physical, or psychological abuse between adolescent romantic partners—is prevalent1,2 with estimates suggesting that approximately one in 10 adolescents are victims of relationship violence.3,4 The health consequences of adolescent relationship violence are varied and can include increased risk of eating disorders, suicidal thoughts or attempts, low self-esteem and poor emotional well-being, substance abuse, risky sexual behaviors, teen pregnancy, and STIs.5–13

While relationship violence poses serious challenges for victims, it may also affect peers because these friends of victims may play an important supportive role. Often such peers do not have the knowledge or skills to handle these situations. To date, little research has explored which adolescents are most likely to seek help from peers, and no study has detailed the range of supports peers report employing to help their friends. The present paper begins to fill these important gaps in the literature by examining in four New York City (NYC) high schools, both the self-reported help-seeking behaviors of adolescent relationship violence victims as well as the range of help-giving behaviors utilized by peers to whom victims disclose. Results will inform the development of interventions designed to assist young people in more effectively responding to relationship violence victimization disclosure by a friend.

Adolescent Help-Seeking Behaviors

Less than half of adolescent victims of relationship violence ever seek help from anyone14 and those that do predominantly disclose to informal support sources like their friends and family rather than formal support sources like health professionals and law enforcement.14–16 Receiving help from informal social supports may have positive effects for victims, including lower levels of depression and anxiety,17 elevated confidence and openness to future help-seeking,18 and for those experiencing less violent relationships, a lower risk of being re-abused than traditionally found among relationship violence victims.19

When adolescent victims disclose to informal support sources, they initially disclose solely to peers in nearly three out of four cases,20 particularly when the victim’s relationship entails less physical violence.21 In fact, as many as 54 % of high school students indicate that they personally know a relationship violence victim.23 Adolescents also turn to peers for support in the case of sexual violence victimization, whether the victimization occurred in or outside of a relationship. According to an analysis of the National Survey of Adolescents, adolescent women whose unwanted sexual experience occurred while they were high school age more often told a peer than told others about the incident.24

This pattern of victims turning to peers for support may in part be due to a perception that peers are less likely than adults to breach confidentiality or blame the victim.24,25 Additionally, adolescents often talk to other adolescents more freely than to adults about their personal lives and romantic relationship problems. Such conversations in turn can lead to victimization disclosures.16 Adolescents are only more likely to reach out to adults than peers when physical violence is severe and escalating, perhaps because adults may be perceived as having more power to intervene.21

Unfortunately, the majority of adolescent victims tell no one about the violence they are experiencing in their relationships. Research consistently finds that males are less likely to seek help than females.21 It has been speculated that this may be due in part to certain masculinity norms that inhibit help-seeking and reporting victimization in general.22 The dearth of victim services designed for men may also serve as a deterrent from seeking formal help. Considerably less attention has been paid by scholars to race–ethnicity and nativity in help-seeking behaviors among adolescents, although an emerging literature suggests that social minority status and cultural norms can inhibit disclosure and help-seeking.26

Adolescent Help-Giving Behaviors

There are three main forms of help identified by the literature that adolescent peers and adults may provide to victims: emotional support (e.g., sympathy, encouragement), advice, and engaging in tasks that help the victim cope with or escape from relationship violence.14 Adults appear to employ all three forms of help with some regularity. According to a large national study, 88 % of adults provided emotional support to victims, approximately half directed victims to a professional agency like the police or shelters, and one in six took action on behalf of the victim either by offering financial support, providing a place for the victim to stay, or helping the victim leave the relationship.27 Preliminary evidence based on responses to hypothetical scenarios suggests that adolescents differ from adults in that adolescents may predominantly provide emotional support,15,28 with friends often being viewed by victims as resources through which to “sort things out” and feel emotionally supported.29 This possible reliance on emotional support from peers with less emphasis on providing advice and taking action may be explained by their youth and lack of experience, whereby they may be less aware of the options available. They also have few instrumental and financial resources available to them. Much of what has been studied about adolescent help-giving behavior is based on responses to hypothetical scenarios rather than their own experiences.15,28 The sole study to explore help-giving responses to actual adolescent victim disclosures assessed emotional support and relied upon victims to report on the help-giving behaviors they received rather than sampling the help-givers directly.16 Research is needed that directly surveys adolescent help-givers about the forms of help they provide.

Given the nascent state of this literature, it is not surprising that research has yet to investigate whether types of help-giving behaviors vary across demographic groups. Additionally, in light of evidence suggesting that minority status and cultural norms can serve to inhibit racial and ethnic minorities and immigrants from seeking out informal help-giving sources26 and since friendships tend to be between members of the same demographic group,30 many friends of minority and immigrant victims in violent relationships are likely to be minorities and immigrants themselves. Thus, it is possible that many of the same cultural, language, and stigma-related barriers that deter minority and immigrant victims from seeking help may also hinder peers from these demographic groups from providing their friends with a wide array of support options. Lastly, it is well-known that there are significant barriers to help-seeking for sexual assault survivors and that those who do decide to seek help face both positive and negative responses,31,32,42 no work to date has been conducted on whether a history of child sexual abuse or relationship violence is associated with the likelihood of providing support and help to a peer who discloses relationship violence.

The present paper represents the first effort in the adolescent relationship violence literature to explore help-giving behaviors as reported by the help-givers, including establishing the prevalence of and factors which predict a broad range of help-giving behaviors. It is also among the first to examine how ethnicity and nativity impact help-seeking behaviors.

Methods

Study Design

This study was conducted in four NYC high schools during the 2006–2007 school year. To identify schools, initial outreach was conducted using convenience sampling. Fifteen potential high schools across the five boroughs of NYC were identified for potential inclusion. Eleven high schools were unable to participate due to the study timing and existing workloads. Four schools expressed interest in participating and were chosen for this study. Three schools were widely distributed in Manhattan, and one school was located in Brooklyn. One of the schools was located within a predominately Latino community. In addition, one school was classified as an alternative transfer high school, meaning students must be at least 16 years old and have attended another high school prior to enrolling. The transfer high school provides students the opportunity to earn their high school diploma in a smaller, student-centered learning community.20 Our study sample follows the same age distribution patterns as NYC Department of Education data for all students in NYC over the same time period.20 Owing to multi-organizational involvement, the protocol and consent for this study were reviewed and approved by three Institutional Review Boards including that of the NYC Department of Education and permission was also received from each of the corresponding School Board Superintendents and School Principals. Passive parental consent was obtained after mailing letters to the parents in English, Spanish, and/or Chinese which contained study information and the opportunity to refuse consent through return of a form in a self-addressed and stamped envelope. Students whose parents refused consent were not invited to participate in the study. Active assent of the student was also requested at the time of survey implementation.

Due to the prevalence of relationship violence among adolescents and the sensitive nature of the survey questions, the study partners felt it was imperative to provide students with referral information for local counseling services. In planning the study, the authors conducted focus groups with young people to develop a youth-friendly referral leaflet specifically for the study. Through this process, the NYC Teen Health Map was developed to provide sexual and relationship violence referral information in a discrete way. The pocketsize foldable maps include a youth-designed cover with a NYC subway map on one side and specific youth referral information for relationship violence and non-partner sexual violence on the other side in small print. In addition to developing the referral maps, the study partners also engaged with young people who acted as evaluators of the services listed to ensure that they were appropriate and responsive to young people. Maps and a brochure about healthy relationships were given to each student in the four participating schools, regardless of study participation. During data collection, trained rape crisis advocates were also available in case a student wanted to talk to someone or receive further information. Several members of the research team were also certified crisis counselors. No student approached the team to discuss any issues that arose as a result of the study, but several of the young people asked for more NYC Teen Health Maps to give to their friends in other schools. Study results were shared with faculty, students, and parents in each school.

Surveys were implemented during the school week in health and physical education classes. Students were offered a $10 gift card to a bookstore for participating (for more detailed methods, see20). Two of the four schools completed an audio computer assisted or ACASI version of the survey, and owing to a lack of computer availability, the other two schools utilized a paper and pencil version. The two school samples using the paper surveys rather than ACASI had significantly greater proportions of females, non-Latinos, and native-born students, but the survey format was not associated with any of the dependent variables of interest regarding help-seeking and help-giving behaviors (χ2, p < 0.05).

Students chose whether they wished to take the survey in English or in Spanish. The participation rate for the study was 70 %. Forty-six parents opted their child out of the study, and 52 youths opted themselves out. Of the 1,454 students who participated and answered at least one survey question, 142 were removed from analysis for extensive missing data.

Survey Measures

Help-Seeking

Help-seeking behavior was assessed through the questions to those reporting the experience of relationship violence, “Did you ever tell anyone about experiencing any physical and sexual violence from a partner,” “Who did you tell first,” and “Who else did you tell?” The response categories for disclosure included parent, doctor or health professional, friend, minister, priest or rabbi, therapist or counselor, and other. Three variables were constructed out of these items for analyses. First, a dichotomous variable assessed whether or not disclosure occurred. Second, among those who had disclosed to someone, a binary variable assessed who was disclosed to first, a friend or an adult. A third variable was constructed that indicated, among those who ever disclosed violence, did they tell only friends or at least one adult. Due to a Spanish translation omitting a word in one question, Spanish language surveys were excluded for help-seeking behavior variables (n = 77). The help-seeking analyses were conducted among adolescents who reported ever experiencing physical or sexual violence within their relationship and who answered the help-seeking questions (n = 126).

Help-Giving

Help-giving behavior was assessed if the adolescent reported that they had a friend in a violent relationship. For all who responded affirmatively, each completed nine follow-up questions about the nature of any support they may have provided across three non-overlapping help-giving domains: talking to their friend, suggesting options, and taking action.Talking to their friend was assessed through the item, “Have you talked to this friend about the violence?” Suggesting options to their friend was assessed through four items asking, “Have you given this friend advice?,” “Have you told him/her to call a hotline?,” “Have you told him/her to talk to an adult?,” and “Have you told him/her to leave this partner?” Taking action on behalf of or with the victim was assessed through four items asking, “Have you called a hotline to figure out how to help your friend?,” “Have you gone with your friend to get some help like at a clinic?,” “Have you talked to the partner directly about his/her violence?,” and “Have you talked to an adult about your friend’s problem?” Cronbach’s alphas were modest for both the suggesting options (α = 0.53) and taking action scales (α = 0.51), suggesting that respondents relied upon a broad range of tactics within these two help-giving categories. The help-giving analyses were conducted with adolescents who reported having a friend in a violent relationship (n = 272).

Relationship Violence Victimization

A history of lifetime physical and sexual relationship victimization was measured using the 23-item Dating Violence Inventory and Family Abuse Scale developed by Symons and colleagues.33 Respondents were asked how often in their lives (ranging from “never” to “4 or more times”) a current or previous partner had used physical relationship violence against them (e.g., “Slapped or hit you,” “Punched you,” “Choked you”) and sexual relationship violence against them (e.g., “Tried to force you into sexual activity,” “Raped you”). For the purposes of analysis, a dichotomous variable was constructed in which respondents were categorized as either having experienced at least one incident of relationship violence victimization (coded 1) or not (coded 0).

Child Sexual Abuse Victimization

Child sexual abuse was measured using a series of questions expanded from those proposed by Symons et al.33 These questions were preceded in the survey by a definition of sexual abuse: “when we ask about ‘sexual abuse,’ we mean any sexual fondling, touching, oral sex or intercourse (penetration of the vagina or anus with a penis, fingers or object).” Respondents were then asked in five separate items, “How often in your life has…your parent sexually abused you or forced you to have sex…a family member other than a parent sexually abused you or forced you to have sex…an older acquaintance (such as a family friend, teacher, minister, neighbor, etc.) sexually abused you or forced you to have sex…someone else your age who you knew but was not your partner sexually abused you or forced you to have sex….and a stranger sexually abused you or forced you to have sex?” Response categories ranged from “never” to “4 or more times.” In analyses, child sexual abuse was coded as a dichotomous variable, where respondents were categorized as either having experienced at least one child sexual abuse incident or not.

Demographic Variables

The demographic variables analyzed in this study include gender, ethnicity, and nativity. Ethnicity was measured with two questions, “Are you of Latino descent or background?” (yes or no) and “Which racial group(s) do you identify with or belong to?” (Black, White, Asian, another racial group). Nativity was assessed through the question, “Were you born in the U.S.?” (yes or no).

Missing Data

Of the full sample of 1,312 respondents, minimal data were missing on gender (missing n = 1), Latino ethnicity (n = 2), national origin (n = 7), age (n = 6), history of child sexual abuse (n = 41), help-seeking variables (n = 40), and whether the respondent ever had a friend in a violent relationship (n = 58). Of those who reported having a friend in a violent relationship, few respondents did not complete the help-giving items on talking to their friend (n = 6), suggesting options (n = 10), and taking action (n = 9). Of the 1,015 respondents who answered in the affirmative to a screening question regarding whether they had ever had a romantic or sexual relationship, only two respondents did not complete all of the survey items on lifetime physical and sexual relationship violence victimization history. Of the variables with the greatest missing data—child sexual abuse, help-seeking, and having a friend disclose relationship violence—two thirds of respondents had missing data on only one of these variables. Males were significantly less likely than females to answer the help-seeking items and the item regarding whether a friend had disclosed relationship violence. Given that little data were missing, listwise deletion of missing cases was used for analyses.

Data Analyses

Univariate analyses were performed on all variables, including demographic variables, relationship and sexual violence victimization histories, help-seeking behaviors, and help-giving behaviors. Bivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to examine help-seeking behaviors to determine if the odds of disclosing to anyone by the time of the survey were associated with gender, Latino ethnicity, and nativity and to determine if the odds of who was disclosed to first, a friend or an adult, are associated with gender, Latino ethnicity, and nativity. Finally, for help-seeking behaviors, bivariate logistic regression was used to determine if gender, Latino ethnicity, and nativity were associated with the odds of ever only disclosing to friends by the time of the survey, relative to ever disclosing to any adult.

For help-giving behaviors, bivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to determine whether the help-giver’s history of child sexual abuse or dating violence victimization was associated with talking with their friend, suggesting options, and taking action with or on behalf of their friend in a violent relationship. Lastly, multiple variable logistic regression explored whether gender, Latino ethnicity, and nativity were associated with talking with their friend, suggesting options, and taking action with or on behalf of their friend in a violent relationship. Since the help-giver’s personal experiences of child sexual abuse and dating violence victimization were not significant predictors of help-giving behaviors in the bivariate analyses, they were not included in the multiple variable regression model in the interest of model parsimony and statistical power. Unlike the multiple variable regression analysis, all other previously mentioned non-univariate analyses were conducted in a bivariate rather than multiple variable regression format due to their smaller model sample sizes.

Results

Sample Description

The demographic characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1. As can be seen, slightly more than half were female, and about half were between the ages of 15 and 16. Almost three quarters of the sample reported Latino ethnicity, while self-reported race varied widely. Finally, about one quarter were born outside of the USA.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sample (n = 1,312)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 14 or younger | 239 (18) |

| 15 to 16 | 628 (48) |

| 17 and older | 439 (34) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 737 (56) |

| Male | 574 (44) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Latino | 962 (73) |

| Non-Latino | 348 (27) |

| Race | |

| Black | 557 (48) |

| White | 87 (7) |

| Asian American | 47 (4) |

| Other | 370 (32) |

| Mixed | 109 (9) |

| Nativity | |

| Born in the USA | 1,001 (77) |

| Born in another country | 304 (23) |

With regard to victimization, 38 % (n = 384) of respondents reported experiencing physical and/or sexual relationship violence at some point in their lifetime, with 36 % (n = 363) reporting physical relationship violence victimization and 10 % (n = 98) sexual relationship violence victimization. Of all respondents, 6 % (n = 81) reported one or more occurrences of experiencing child sexual abuse in their lifetime.

Help-Seeking Behaviors

Of youth who had experienced relationship violence (physical and/or sexual) and answered the help-seeking questions, 61 % (n = 78) told someone about that violence by the time of the survey. According to bivariate logistic regression models predicting the help-seeking variables, among those who experienced relationship violence in their lifetime, male victims were significantly less likely than female victims to seek help (odds ratio (OR) = 0.27, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.13–0.60). However, there were no significant differences in help-seeking behavior by ethnicity or nativity for adolescents who had experienced relationship violence.

Gender and nativity were not associated with the type of people ever disclosed to for relationship violence. Relationship violence victims who had disclosed were more likely to choose their friends for informal support. Of those that disclosed their experiences of relationship violence victimization, a small percentage (12 %, n = 9) had only told an adult about the violence, nearly half (46 %, n = 36) had only ever told a friend but no adult, and 42 % (n = 33) had told both an adult and a friend. Additionally, the first person initially disclosed to was a friend for 72 % of relationship violence victims.20 Turning to the bivariate logistic regression results in Table 2, Latinos were found to be significantly less likely to ever disclose only to friends, as compared to ever disclosing to at least one adult. Table 3 highlights that Latinos had significantly lower odds than non-Latinos of telling a friend first (as opposed to an adult) about their relationship violence victimization.

Table 2.

Bivariate logistic regression analysis of help-seeker characteristics predicting help-seeking behaviors among respondents who reported ever disclosing relationship violence (n = 78)

| Predictor | Disclosed to adults(s)a | Only disclosed to friend(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 42 | n = 36 | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | OR | 95 % CI | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 8 (19) | 10 (28) | 1.67 | 0.54, 5.15 |

| Female | 34 (81) | 26 (72) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Latino | 35 (83) | 21 (58) | 0.28* | 0.10, 0.81 |

| Other | 7 (17) | 15 (42) | ||

| Nativity | ||||

| Foreign Born | 32 (76) | 29 (81) | 0.68 | 0.21, 2.16 |

| US Born | 10 (24) | 7 (19) | ||

OR odds ratio

*p < 0.05

aIncludes respondents who ever disclosed to only adults or ever disclosed to friends and adults

Table 3.

Bivariate logistic regression analysis of help-seeker characteristics predicting who was disclosed to first (n = 78)

| Predictors | Y: initial disclosure outlet | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosed to adult first (reference group; n = 22) | Disclosed to friend first (n = 56) | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | OR | 95 % CI | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 5 (23) | 13 (23) | 1.02 | 0.32, 3.32 |

| Female | 17 (77) | 43 (77) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Latino | 20 (91) | 36 (64) | 0.18** | 0.04, 0.850 |

| Other | 2 (.09) | 20 (36) | ||

| Nativity | ||||

| Foreign born | 16 (73) | 45 (80) | 0.65 | 0.21, 2.05 |

| US born | 6 (27) | 11 (20) | ||

Each bivariate analysis included one predictor and the dependent variable, although all predictors are presented here for ease of comparison

OR odds ratio

**p < 0.01

Help-Giving Behaviors

Over a fifth (22 %) of the students reported that they had a friend currently in a violent relationship (n = 272). Of these students, 69 % identified as female, 66 % identified as Latino, and 81 % were born in the USA.

Adolescents responded to their friends’ situation in a variety of ways (Table 4). Some of the more common approaches included talking with the friend about the violence (79 %), giving advice (82 %), telling the friend to leave the partner (80 %), talking directly to the friend’s partner about the violence (52 %), telling the friend to talk to an adult about the violence (50 %), and talking to an adult about the friend’s experience of violence (47 %). Among the least commonly employed tactics were calling a hotline on behalf of the friend (14 %) and advising the friend to call a hotline (19 %).

Table 4.

Frequencies of help-giving behaviors

| Type of help given | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Talked with friend | 209 (79.2) |

| Offered suggestions | 242 (91.3) |

| Gave friend advice | 216 (81.5) |

| Told friend to call hotline | 49 (18.6) |

| Told friend to talk to adult | 134 (50.4) |

| Told friend to leave partner | 209 (80.1) |

| Took action | 201 (76.0) |

| Talked with friend’s partner directly | 137 (51.9) |

| Called a hotline | 36 (13.5) |

| Talked to an adult about friend | 124 (46.6) |

| Went with friend to get services | 83 (31.4) |

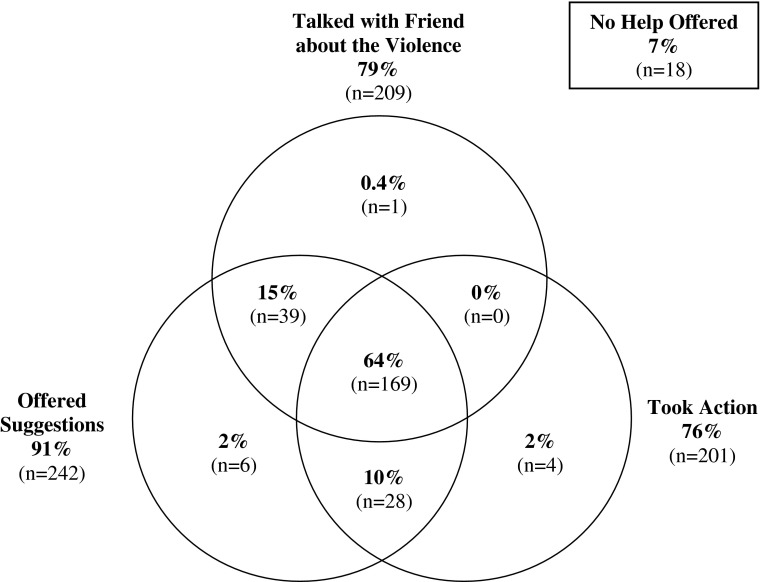

Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the types of help given by adolescents to their friends. From this diagram, we can see that very few adolescents gave only one form of help to their friends who were in a violent relationship, with the majority of adolescents (64 %) providing all three types of help—talking to their friends, suggesting options to their friends, and taking action on behalf of or with their friends.

FigURE 1.

Venn diagram of types of help given to friends experiencing relationship violence. Subsample analyzed includes respondents who provided help to a peer for IPV victimization and who had complete data on all three help-giving scales (n = 265)

As can been seen in the bivariate logistic regressions (Table 5), help-givers’ histories of relationship violence victimization and child sexual abuse victimization were not significantly associated with any type of help-giving behavior. However, we did find that males were less likely than females to give all forms of help to their friends. The only significant difference in help-giving behaviors by ethnicity was that Latinos were more likely than non-Latinos to take action. Foreign-born adolescents had significantly lower odds than US-born young people of talking to their friends about the violence as well as suggesting options for their friends, while there was no significant difference between the two groups with regards to taking action to help their friends.

Table 5.

Analysis of which help-giver characteristics predicted help-giving behaviors: bivariate logistic regressions

| Predictors | Y1: talk with friend | Y2: suggest options | Y3: take action | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.37** | 0.20, 0.69 | 0.24* | 0.09, 0.58 | 0.38** | 0.21, 0.69 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Latino | 0.91 | 0.48, 1.70 | 1.56 | 0.65, 3.71 | 2.22* | 1.25, 3.95 |

| Nativity | ||||||

| Foreign born | 0.38* | 0.19, 0.74 | 0.32* | 0.13, 0.79 | 1.20 | 0.57, 2.50 |

| History of relationship violence | 1.04 | 0.54, 2.00 | 0.56 | 0.20, 1.57 | 1.04 | 0.56, 1.93 |

| History of child sexual abuse | 0.59 | 0.24, 1.44 | –a | 0.75 | 0.31, 1.81 | |

Each bivariate analysis included one predictor and the dependent variable, although all predictors are presented here for ease of comparison

OR odds ratio

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

aSub-sample size too small to draw statistical conclusions

Table 6 displays the adjusted odds of help-giving to friends experiencing relationship violence. We found that after controlling for ethnicity and nativity, males were significantly less likely to give all forms of help to their friends. Foreign-born adolescents were significantly less likely to talk to their friends and suggest options to their friends, but there was no significant difference regarding taking action on behalf of, or together with, friends experiencing relationship violence. After adjusting for gender and nativity, Latinos were nearly twice as likely as non-Latinos (OR (95 % CI) = 1.91 (1.06, 3.46)) to take action to help to their friends, but no significant differences were found between these two groups regarding the other help-giving behaviors.

Table 6.

Analysis of which help-giver characteristics predicted help-giving behaviors: multiple variable logistic regressions

| Predictors | Y1: talk with friend | Y2: suggest options | Y3: take action | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.38* | 0.20, 0.71 | 0.25* | 0.10, 0.63 | 0.41* | 0.23, 0.75 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Latino | 0.79 | 0.40, 1.53 | 1.30 | 0.52, 3.23 | 1.91* | 1.06, 3.46 |

| Nativity | ||||||

| Foreign born | 0.39* | 0.19, 0.78 | 0.32* | 0.13, 0.81 | 1.26 | 0.59, 2.69 |

All three models adjusted for gender, ethnicity, and nativity

OR odds ratio

*p < 0.05

Discussion

Adolescents are in a unique position to provide support to peers involved in relationship violence. Over a fifth of all respondents reported currently having a friend in a violent relationship. Moreover, our research shows that the majority of relationship violence victims (72 %) who disclose their experiences with relationship violence disclose to their friends first, with approximately nine in ten victims ever disclosing to peers by the time of the survey.

One promising finding from our research is that adolescent help-givers of their peers who were victims of relationship violence readily provide all three forms of assistance that were asked about in the survey, including taking action (accounting for 76 % of respondents who knew a relationship violence victim), talking with their friend about the violence (79 %), and, most commonly, offering suggestions (91 %). Two thirds of help-givers gave all three types of support. At the same time, the specific tactics taken within these three help-giving strategies leaned toward helping the victim escape the abuser without the assistance of professionals who may be particularly valuable in maintaining the safety of escaping victims. Among the more commonly given suggestions, 80 % of adolescents told their friend to leave the abuser. While revealing empathy by the peer supporter and having the potential for positive outcomes, without accompanying expert-provided advice and assistance, an escaping victim may be at risk of retribution by the abuser.34 Likewise, the most common action taken (for 52 % of help-givers) was talking directly with the friend’s abuser, which similarly has the potential to pose safety risks to the victim and the help-giver.34 By comparison, only 19 % recommended that the victims reach out to professional help through a hotline, and only 14 % of help-givers called a hotline on behalf of their friend. While hotline expertise was not typically sought out, the assistance of adults often was, with 50 % suggesting to the victim that he or she should talk to an adult and 47 % talking to an adult on behalf of the victim. Ultimately, the finding that adolescents are highly likely to respond to the needs of their victimized peers suggests that programs designed to better support and educate adolescents about help-giving may have positive and far-reaching implications for adolescent victims of relationship violence.

As for difference between demographic groups, ethnicity was predictive of whom adolescents disclosed to, whereas gender and nativity were not. Latinos were significantly less likely than non-Latinos to ever disclose only to friends, as compared to disclosing to at least one adult. In line with the empirical literature and theories of masculinities performance, males were less likely to ever seek help.22 There was no association between foreign birth and help seeking, though Latino adolescent victims were more likely than non-Latinos to seek help, suggesting that minority status may increase the likelihood to reach for help regardless of gender. Regarding who gave each form of help, in line with the literature, males were significantly less likely than females to give all forms of help to their friends according to multiple variable regression analyses. One unexpected finding is that Latinos were significantly more likely to take action to help their friends than non-Latinos. After controlling for ethnicity and gender, data showed that foreign-born adolescents (of which 80 % were Latino) were less likely than US-born young people to both talk to and suggest options to their friends, while there was no difference between the two for taking action with or on behalf of their friend in a violent relationship. Further exploration is needed regarding Latino and foreign-born adolescents’ help-giving to friends experiencing relationship violence. Specifically, future research could inquire as to whether forms of help-giving are encouraged in part by family and peer socialization and by overall cultural value systems.

This is the first paper to ask adolescent help-givers to self-report the help they provide, the first to provide information on which forms of help are most often given as well as who is most likely to give it, and among the first to assess how ethnicity and nativity affect help-seeking. Beyond the need for replication—including in adolescent samples with different ethnic compositions—a logical next step for research is to document which forms of help are perceived by the victim to be most helpful and are associated with the most positive outcomes. Research suggests that informal help-giving may not always have positive outcomes,35–37 and determining which approaches are most successful would be instrumental in beginning to craft adolescent programs that educate adolescents about help-giving strategies. One limitation of the present study is that the help-giving questions are of self-reported behaviors, and it was not possible to cross-validate or match responses with those of the victims on help received. By recruiting both victims of relationship violence and the peers that helped them, the degree of agreement between them on the nature of the help provided can be assessed, and it could be determined whether research on help-giving is most accurately done with samples comprised of victims, help-givers, or both. Although our data do not allow such analyses, future research would also do well to explore the impact of involvement with “reciprocal” relationship violence on adolescent help-seeking and help-giving behaviors. Lastly, the help giving questions offered a limited number of categories for the types of help offered or accepted. Qualitative research might assist in a more finely grained understanding of how adolescents define their own approaches.

Although policy implications may be premature, clearly adolescents often rely on each other for support in facing relationship violence, so it is important that adolescents receive training and education on how to best help their friends, including when and how to make referrals to more formal services. Programs already exist that could provide a model framework for peer program development, including bystander intervention programs such as Mentors in Violence Prevention,38 relationship violence interventions such as the Safe Dates evaluated school-based curriculum which includes help-giving training for adolescents,39 and peer crisis intervention models such as the Rape Crisis Advocate model from the sexual violence field40 and System Navigators from the HIV field.41 These four programs train volunteers (often peers and members of the community) in crisis response skills such as active listening as well as how to navigate formal systems to provide support to the person in crisis.

Adolescents are often the first and last resources in supporting adolescent relationship violence victims—and it is for this particular reason that researchers and policymakers alike should further our understanding of and response to this valuable role played by adolescent peers of victims.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the New York City Council and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies or views of the funders.

References

- 1.Rennison CM. Special Report: Intimate Partner Violence and Age of Victim, 1993–99. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2001.

- 2.O’Leary KD. Developmental and affective issues in assessing and treating partner aggression. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1999;6:400–14. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.6.4.400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(SS-4). [PubMed]

- 4.Halpern CT, Oslak SG, Young ML, Martin SL, Kupper LL. Partner violence among adolescents in opposite-sex romantic relationships: findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(10):1679–85. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.10.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson MJ. Health behavior in adolescent women reporting and not reporting intimate partner violence. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010;39:263–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2010.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gidycz CA, Orchowski LM, King CR, Rich CL. Sexual victimization and health-risk behaviors: a prospective analysis of college women. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(6):744–63. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ackard DM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Long-term impact of adolescent dating violence on the behavioural and psychological health of male and female youth. J Pediatr. 2007;151(5):476–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton DK, Davis KS, Barrios L, Brener ND, Noonan RK. Associations of dating violence victimization with lifetime participation, co-occurrence, and early initiation of risk behaviors among U.S. high school students. J Interpers Violence. 2007;22:585–602. doi: 10.1177/0886260506298831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman JG, Raj A, Clements K. Dating violence and associated sexual risk and pregnancy among adolescent girls in the United States. Pediatrics. 2004;114:220–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.e220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan P. Dating violence among a nationally representative sample of adolescent girls and boys: associations with behavioral and mental health. J Gend Specif Med. 2003;6(3):39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Date violence and date rape among adolescents: associations with disordered eating behaviors and psychological health. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:455–73. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci L, Hathaway J. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. JAMA. 2001;286:573–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coker AL, Smith PH, Bethea L, King MR, McKeown RE. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(5):451–7. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashley OS, Foshee VA. Adolescent help-seeking for dating violence: prevalence, sociodemographic correlates, and sources of help. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ocampo BW, Shelley GA, Jaycox LH. Latino teens talk about help-seeking and help-giving in relation to dating violence. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(2):172–89. doi: 10.1177/1077801206296982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weisz AN, Tolman RM, Callahan MR, Saunders DG, Black BM. Informal helpers’ responses when adolescents tell them about dating violence or romantic relationship problems. J Adolesc. 2007;30(5):853–68. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson BE, McNutt L, Choi DY, Rose IM. Intimate partner abuse and mental health: the role of social support and other protective factors. Violence Against Women. 2002;8:720–45. doi: 10.1177/10778010222183251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waldrop AE, Resick PA. Coping among adult female victims of domestic violence. J Fam Violence. 2004;19:291–302. doi: 10.1023/B:JOFV.0000042079.91846.68. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman L, Dutton MA, Vankos N, Weinfurt K. Women’s resources and use of strategies as risk and protective factors for reabuse over time. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(3):311–36. doi: 10.1177/1077801204273297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fry, D., Davidon, L.L., Rickert, V.I. Lessel, H. Partners and peers: sexual and dating violence among NYC youth. A research report by the NYC Alliance against Sexual Assault in Conjunction with the Columbia University Centre for Youth Violence Prevention. New York: New York City Alliance Against Sexual Assault; 2008.

- 21.Ansara DL, Hindin MJ. Formal and informal help-seeking associated with women’s and men’s experience of intimate partner violence in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1011–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Courtenay WH. Key determinants of the health and well-being of men and boys. Int J Men’s Health. 2003;2(1):1–30. doi: 10.3149/jmh.0201.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaffe P, Sudermann M, Reitzel D, Killip S. An evaluation of a secondary school primary prevention program on violence in intimate relationships. Violence Vict. 1992;7:129–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krogan S. Disclosing unwanted sexual experiences: results from a national sample of adolescent women. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28(2):147–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foshee VA, Linder GF, Bauman KE, Langwick SA, Arriaga XB, Heath JL, et al. The safe dates project: theoretical basis, evaluation, design, and selected baseline findings. Am J Prev Med. 1996;12(5):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang B, Goodman L, Tummala-Narra P, Weintraub S. A theoretical framework for understanding helpseeking processes among survivors of intimate partner violence. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;36:71–84. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-6233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beeble ML, Lori A, Post DB, Sullivan CM. Factors related to willingness to help survivors of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(12):1713–29. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallopin C, Leigh L. Teen perceptions of dating violence, help-seeking and the role of schools. Prev Res. 2009;16:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson SM, Cram F, Seymour FW. Violence and sexual coercion in high school students’ dating relationships. J Fam Violence. 2000;15:23–36. doi: 10.1023/A:1007545302987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McPherson JM, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:415–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ullman SE. Social support and recovery from sexual assault: a review. Aggress Violent Behav: Rev J. 1999;4(3):343–58. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(98)00006-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell R. The psychological impact of rape victims’ experiences with the legal, medical, and mental health systems. Am Psychol. 2008;63:702–17. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.8.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Symons PY, Groer MW, Kepler-Youngblood P, Slater V. Prevalence and predictors of adolescent dating violence. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 1994;7(3):14–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.1994.tb00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin AJ, Berenson KR, Griffing S, Sage RE, Madry L, Bingham LE, et al. The process of leaving an abusive relationship: the role of risk assessments and decision-certainty. J Fam Violence. 2000;15(2):109–22. doi: 10.1023/A:1007515514298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trotter JL, Allen NE. The good, the bad and the ugly: domestic violence survivors experience with their informal social networks. Community Psychol. 2009;43(4):221–31. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodkind JR, Gillum TL, Bybee DI, Sullivan CM. The impact of family and friends’ reactions on the well-being of women with abusive partners. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:347–73. doi: 10.1177/1077801202250083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West A, Wandrei ML. Intimate partner violence: a model for predicting interventions by informal helpers. J Interpers Violence. 2002;17:972–86. doi: 10.1177/0886260502017009004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz J, Heisterkamp HA, Fleming WM. The social justice roots of the Mentors in violence prevention model and its application in a high school setting. Violence Against Women. 2011;17:684–702. doi: 10.1177/1077801211409725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Ennett ST, Suchindran C, Benefield T, Linder GF. Assessing the effects of the dating violence prevention program ‘safe dates’ using random coefficient regression modelling. Prev Sci. 2005;6(3):245–58. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell R. Rape survivors’ experiences with the legal and medical systems: do rape victim advocates make a difference? Violence Against Women. 2006;12(1):30–45. doi: 10.1177/1077801205277539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vargas RB, Cunningham WE. Evolving trends in medical care-coordination for patients with HIV and AIDS. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2006;3(4):149–53. doi: 10.1007/s11904-006-0009-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeitler MS, Paine AD, Breitbart V, Rickert VI, Olson C, Stevens L, et al. Attitudes about intimate partner violence screening among an ethnically diverse sample of young women. J Adol Med. 2006;39:119.e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]