Abstract

Federal and state policies on eligibility to purchase and possess firearms and background check requirements for firearm transfers are undergoing intensive review and, in some cases, modification. Our objective in this third report from the Firearms Licensee Survey (FLS) is to assess support among federally licensed firearms retailers (gun dealers and pawnbrokers) for a background check requirement on all firearm transfers and selected criteria for denying the purchase of handguns based on criminal convictions, alcohol abuse, and serious mental illness. The FLS was conducted by mail during June–August, 2011 on a random sample of 1,601 licensed dealers and pawnbrokers in 43 states who were believed to sell at least 50 firearms annually. The response rate was 36.9 %, typical of establishment surveys using such methods. Most respondents (55.4 %) endorsed a comprehensive background check requirement; 37.5 % strongly favored it. Support was more common and stronger among pawnbrokers than dealers and among respondents who believed that “it is too easy for criminals to get guns.” Support was positively associated with many establishment characteristics, including sales of inexpensive handguns, sales that were denied when the purchasers failed background checks, and sales of firearms that were later subjected to ownership tracing, and were negatively associated with sales at gun shows. Support for three existing and nine potential criteria for denial of handgun purchase involving criminal activity, alcohol abuse, and mental illness exceeded 90 % in six cases and fell below 2/3 in one. Support again increased with sales of inexpensive handguns and denied sales and decreased with sales of tactical (assault-type) rifles. In this survey, which was conducted prior to mass shootings in Aurora, Colorado; Oak Creek, Wisconsin; Newtown, Connecticut; and elsewhere, licensed firearm sellers exhibited moderate support for a comprehensive background check requirement and very strong support for additional criteria for denial of handgun purchases. In both cases, support was associated with the intensity of respondents’ exposure to illegal activities.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11524-013-9842-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Firearms, Crime, Violence, Alcohol, Firearms policy, Federal firearms licensees

Introduction

Firearm violence “poses a serious threat to the safety and welfare of the American public,”1 with mortality rates that have remained essentially unchanged for more than a decade.2,3 There were an estimated 467,321 firearm-related violent crimes in the USA in 2011, a 26 % increase since 2008.4 Fear of becoming an unintended victim of gunfire intended for someone else is widespread and alters the pattern of life in entire communities.5–7

As one means of preventing firearm violence, federal statute prohibits the purchase and possession of firearms by persons convicted of any felony or a “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence,” anyone who is “an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance,” has been “adjudicated as a mental defective” or “committed to any mental institution,” and others.8 (For simplicity’s sake, “purchase” and “sale” will be used here to refer to acquisitions and transfers of all types.) Recent Supreme Court decisions have affirmed that any individual right to purchase and possess firearms is subject to restriction,9,10 but there is no agreement on what those restrictions should be.

To identify prohibited persons as they attempt to acquire firearms, the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act requires that a background check be performed for purchases from federal firearms licensees (FFLs) such as firearms dealers and pawnbrokers. In 2010, federal and state agencies conducted 10.4 million background checks; more than 150,000 purchases were denied when background checks found the buyers to be prohibited persons.11

While background checks and denials appear to reduce risk for subsequent violent and firearm-related crime among those whose purchases are denied,12–14 the Brady Act has been found have no effect on rates of firearm homicide.15 The Act’s requirements, however, do not apply to firearm transfers by unlicensed private parties. These account for some 40 % of firearm acquisitions overall in the USA16 and at least 80 % of acquisitions made with criminal intent.17–19 In addition, federal denial criteria are limited in scope, and identifiable subgroups of persons who legally purchase firearms under those criteria are at greatly increased risk for committing subsequent crimes.19–21

States have acted to address these gaps in federal regulation. Six states have longstanding policies requiring background checks for all firearm purchases, including private party sales, and 10 others have required checks for all handgun sales or sales at gun shows.22 In 2013, four of these 10 states (Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland, and New York) and Delaware have enacted comprehensive background check requirements. Many states have at one time or another enacted additional criteria for denial of purchase, such as alcohol abuse and convictions for violent misdemeanors.22

In 2011, we conducted the Firearms Licensee Survey, an establishment survey of FFLs, in part to assess their support for a comprehensive background check policy and selected current and potential criteria for denial of purchase.23,24 Our target population was the owners, managers, or other senior executives of FFLs that were actively engaged in retail firearm sales. This population has uniquely detailed knowledge of the operations of retail firearm commerce and would be directly involved in implementing any such policies.

Our primary hypothesis was that respondents would support a comprehensive background check policy and all suggested denial criteria. Our secondary hypothesis was that support would increase with respondents’ exposure to illegal activity involving the purchase and use of firearms: attempted illegal transactions, including surrogate or “straw” purchases and off-the-books purchases; denied sales; and sales of firearms that were later recovered by law enforcement agencies and subjected to ownership tracing, generally following use in a crime.

Methods

The design and execution of the survey have been described in detail in this journal23 and elsewhere;24 those descriptions are summarized here. We use “retailer” only to refer to an individual person.

Identifying the Study Population

We used the February 2011 FFL roster25 to identify 55,020 retail licensees: dealers and gunsmiths (Type 01 licenses), and pawnbrokers (Type 02 licenses). We restricted study eligibility to the 9,720 retail licensees who sold an estimated 50 or more firearms annually, based on data supplied by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (see supplementary material). These data were not available for seven states. A random sample of 1,601 licensees in the 43 remaining states, stratified by license type, was drawn using PROC SURVEYSELECT in SAS software.26 The sample size was chosen to provide 95 % confidence intervals of ±3 % when equal proportions of respondents provided alternate responses to questions with two possible answers and the response rate was 60 %.27

Questionnaire Design

We followed validated recommendations by Dillman and colleagues in designing the questionnaire (see supplementary material).27,28 Where feasible, questions were constructed to facilitate comparisons to previous survey research.29,30

The question on comprehensive background checks was preceded by this brief introduction: “When you sell a gun as a licensed retailer, the buyer usually must go through a background check. In most states, this background check requirement does not apply to gun sales by private individuals. Some retailers believe this is a problem, because prohibited persons can easily buy guns if there is no background check.” Subjects were then asked, “How strongly would you favor or oppose requiring that gun sales by private individuals include background checks?” Five response options ranged from “strongly favor” to “strongly oppose.”

The questionnaire next presented a list of seven crimes (aggravated assault, involving a lethal weapon or serious injury; armed robbery; possession of equipment for illegal drug use; assault and battery, not involving a lethal weapon or serious injury; assault and battery on an intimate partner: domestic violence; resisting arrest; publicly displaying a firearm in a threatening manner) and asked subjects in each case to “indicate whether you think persons who have been convicted of the crime SHOULD or SHOULD NOT be able to purchase handguns.” Finally, subjects were presented with 5 “conditions involving alcohol, drugs, and mental illness” and asked to respond as just described.

As reported previously,23,24 subjects provided demographics and their general attitudes about firearms and working in the firearms industry. They gave detailed information about their business practices, including the number and types of firearms sold (assault-type rifles were described as “tactical or modern sporting” rifles); sales at gun shows and over the Internet; and sales to women, law enforcement officers, and purchasers who bought multiple firearms in a short period of time. They specified how frequently they received requests for assistance in tracing a firearm and the percentage of their sales that were denied following a background check. They reported how often they experienced attempts to buy firearms illegally, through surrogate (straw) purchases and purchases without background checks, and whether firearms had been stolen from their business inventory. Finally, they estimated the percentage of licensed retailers who “knowingly participate in illegal gun sales” and gave recommended terms of incarceration for an individual who purchased, and a licensed retailer who knowingly sold, 50 firearms as part of a “gun trafficking operation.”

Survey Implementation

We conducted the survey by mail, again following validated procedures recommended by Dillman and colleagues,27 beginning June 16, 2011 (see supplementary material). This time of slower business activity31 was chosen to improve the response rate.

The survey protocol required up to three questionnaire mailings; we included a $3 cash incentive in the first. We sent personalized letters to the chief executive or regulatory officer of the 25 corporations with more than one licensee in our sample, requesting that they authorize store managers to participate.

Data management and statistical analysis

We determined response and refusal rates and questionnaire completeness using guidelines set by the American Association for Public Opinion Research.32 The response rate was the percentage of subjects in the sample who returned filled-out questionnaires. Complete questionnaires provided answers to >80 % of questions, partial questionnaires to 50–80 %, and break-off questionnaires to <50 %.

All licensees in the sample were categorized by general business structure: the licensee was an individual named person; the licensee was a corporation, and only one establishment owned by that corporation appeared in the sample (corporate/single site); the licensee was a corporation, and multiple establishments owned by that corporation appeared in the sample (corporate/multisite). Respondents known not to be owners, managers, or other senior executives (n = 21) or of undetermined status (n = 27) were excluded from the analysis. A categorical variable summarizing the number of new denial criteria endorsed by respondents was specified as all 9, 7–8, ≤6.

We used binary and ordinal logistic regression, expressing results as Odds Ratios (ORs) with 95 % Confidence Intervals (CIs), to model associations between outcome and explanatory variables. For multivariable models, variables with p < 0.20 in bivariate regression were entered into an initial model, with elimination in order of decreasing p until remaining variables had p ≤ 0.10. The threshold for statistical significance was p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.1.3 for Windows.26

The UC Davis institutional review board approved this project.

Results

The response rate was 36.9 % (591 of 1,601). Of the returned questionnaires, 96.3 % were complete and 3.7 % were partial. Response rates for dealers and pawnbrokers were similar: 37.2 and 36.3 %, respectively, p = 0.75. The response rate for employees of corporate/multisite licensees (19.7 %) was less than half that for employees of corporate/single site licensees (41.1 %) or licensees who were named individual persons (40.5 %), p < 0.0001. Further detail on response rated is reported elsewhere.23,24 Completion rates for questions on background checks and denial criteria were ≥97 %.

Comprehensive Background Checks

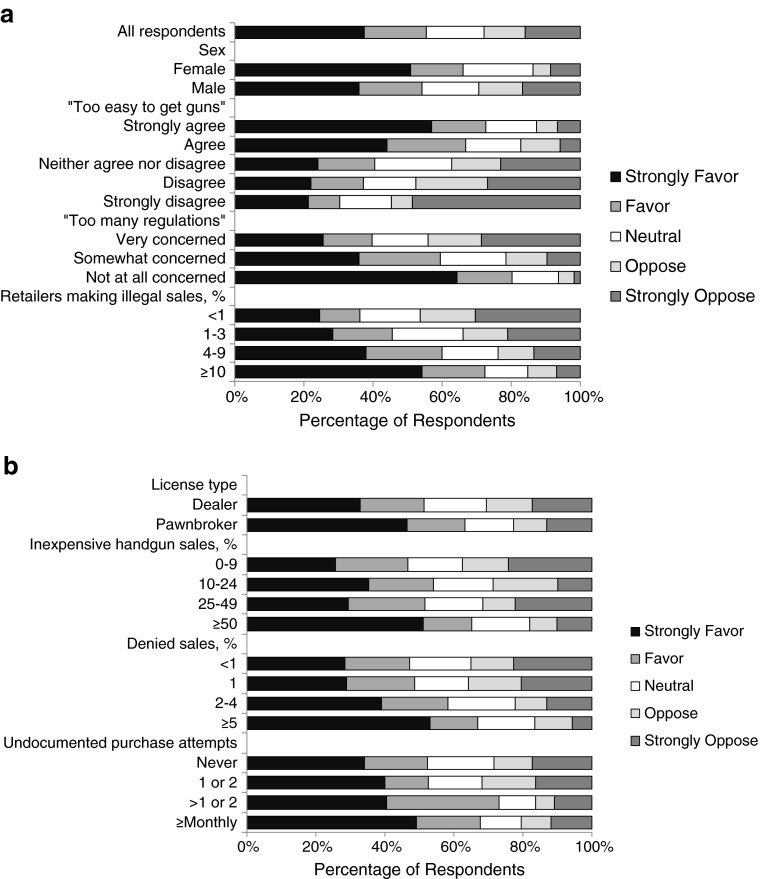

Most respondents (55.4 %) supported a comprehensive background check requirement, and a plurality (37.5 %) strongly favored it (Fig. 1a). Altogether, 27.9 % of respondents opposed the requirement; 15.9 % were strongly opposed. Both the prevalence and strength of support for comprehensive background checks were greater among women and increased with respondents’ agreement that “it is too easy for criminals to get guns,” the severity of the sentence they recommended for illegal firearm purchasing, and their estimate of the prevalence of knowing participation in illegal gun sales by other retailers (Fig. 1a, Table 1). Support decreased sharply with the extent to which respondents were concerned that “there are too many ‘gun control’ regulations.”

Figure 1.

Support for or opposition to “requiring that gun sales by private individuals include background checks.” a For all respondents and by sex, agreement with the statement that “it is too easy for criminals to get guns in this country,” concern that “there are too many ‘gun control’ regulations,” and estimated percentage of licensed retailers “who participate knowingly in illegal gun sales.” b By license type, sales of inexpensive handguns and denied sales, and frequency of attempts by buyers to purchase firearms without required forms and a background check. Note: Inexpensive handgun sales are expressed as a percentage of handgun sales and denied sales as a percentage of all firearm sales.

Table 1.

Bivariate association between respondent and establishment characteristics, support for a comprehensive background check policy, and number of criteria endorsed for denying the purchase of handguns

| Characteristic | Comprehensive background check policy | Criteria for denying the purchase of handguns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | p | OR | 95 % CI | p | |

| Respondent characteristics | ||||||

| Age, years | 0.49 | 0.28 | ||||

| <40 | 1.34 | 0.81–2.22 | 0.76 | 0.44–1.31 | ||

| 40–64 | 1.09 | 0.73–1.62 | 0.70 | 0.46–1.09 | ||

| ≥65 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Sex | 0.01 | 0.06 | ||||

| F | 1.89 | 1.14–3.13 | 1.67 | 0.98–2.86 | ||

| M | Referent | Referent | ||||

| “It is too easy for criminals to get guns” | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Strongly agree | 9.20 | 4.53–18.71 | 4.86 | 2.25–10.49 | ||

| Agree | 6.10 | 3.06–12.17 | 3.67 | 1.73–7.81 | ||

| Neutral | 2.23 | 1.12–4.47 | 1.76 | 0.82–3.79 | ||

| Disagree | 1.77 | 0.86–3.64 | 1.44 | 0.65–3.22 | ||

| Strongly disagree | Referent | Referent | ||||

| “I might sell a gun that gets used in a crime” | 0.002 | 0.91 | ||||

| Very concerned | 1.99 | 1.34–2.96 | 1.09 | 0.71–1.66 | ||

| Somewhat concerned | 1.54 | 1.08–2.19 | 1.01 | 0.69–1.48 | ||

| Not at all concerned | Referent | Referent | ||||

| “There are too many gun control regulations” | <0.0001 | 0.004 | ||||

| Very concerned | 0.15 | 0.09–0.23 | 0.48 | 0.31–0.75 | ||

| Somewhat concerned | 0.34 | 0.22–0.54 | 0.72 | 0.46–1.13 | ||

| Not at all concerned | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Recommended incarceration for buyer in trafficking operation, years | 0.002 | 0.008 | ||||

| ≥20 | 1.94 | 1.24–3.04 | 2.17 | 1.34–3.51 | ||

| 11–19 | 1.11 | 0.67–1.84 | 1.90 | 1.10–3.29 | ||

| 6–10 | 1.89 | 1.29–2.77 | 2.06 | 1.38–3.08 | ||

| 0–5 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Estimated proportion of retailers who make illegal sales, % | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| ≥10 | 4.43 | 2.56–7.69 | 2.54 | 1.46–4.12 | ||

| 4–9 | 2.44 | 1.38–4.30 | 1.11 | 0.62–1.99 | ||

| 1–3 | 1.40 | 0.84–2.32 | 0.87 | 0.52–1.47 | ||

| <1 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Recommended incarceration for seller in trafficking operation, years | 0.10 | 0.004 | ||||

| ≥20 | 1.60 | 1.04–2.45 | 2.41 | 1.52–3.83 | ||

| 11–19 | 1.46 | 0.88–2.42 | 2.02 | 1.17–3.46 | ||

| 6–10 | 1.46 | 0.98–2.17 | 1.97 | 1.30–3.00 | ||

| 0-5 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Establishment characteristics | ||||||

| Licensee type | 0.002 | 0.53 | ||||

| Pawnbroker | 1.65 | 1.19–2.27 | 1.11 | 0.79–1.56 | ||

| Dealer | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Sales in 2010, n | 0.94 | 0.71 | ||||

| ≥500 | 1.05 | 0.66–1.64 | 0.80 | 0.49–1.29 | ||

| 200–499 | 1.13 | 0.72–1.76 | 0.79 | 0.48–1.26 | ||

| 100–199 | 1.14 | 0.71–1.82 | 0.91 | 0.55–1.50 | ||

| <100 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Handgun sales, %a | 0.29 | 0.10 | ||||

| ≥75 | 1.13 | 0.65–1.96 | 0.58 | 0.32–1.04 | ||

| 50–74 | 0.94 | 0.62–1.43 | 1.04 | 0.67–1.61 | ||

| 25–49 | 0.70 | 0.44–1.12 | 0.72 | 0.44–1.18 | ||

| 0–24 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Inexpensive handgun sales, %b | <0.0001 | 0.001 | ||||

| ≥50 | 2.74 | 1.80–4.15 | 2.26 | 1.45–3.52 | ||

| 25–49 | 1.23 | 0.77–1.95 | 1.16 | 0.70–1.92 | ||

| 10–24 | 1.60 | 1.03–2.47 | 1.11 | 0.69–1.79 | ||

| 0–9 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Sales to women, %a | 0.89 | 0.94 | ||||

| ≥25 | 0.97 | 0.64–1.47 | 0.96 | 0.62–1.50 | ||

| 11–24 | 1.04 | 0.69–1.58 | 0.88 | 0.56–1.37 | ||

| 6–10 | 0.87 | 0.57–1.35 | 1.00 | 0.63–1.60 | ||

| 0–5 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Sales to law enforcement, %a | 0.85 | 0.30 | ||||

| 10+ | 1.03 | 0.65–1.61 | 1.05 | 0.65–1.68 | ||

| 5–9 | 0.93 | 0.57–1.49 | 0.69 | 0.41–1.14 | ||

| ≥1, <5 | 1.12 | 0.71–1.77 | 0.88 | 0.54–1.43 | ||

| <1 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Multiple sales, %a | 0.37 | 0.55 | ||||

| ≥5 | 1.11 | 0.73–1.71 | 0.72 | 0.45–1.14 | ||

| 2–4 | 0.81 | 0.52–1.25 | 0.90 | 0.56–1.45 | ||

| 1–1.9 | 0.81 | 0.53–1.24 | 0.88 | 0.56–1.38 | ||

| <1 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Tactical rifle sales, %c | 0.10 | 0.02 | ||||

| ≥20 | 0.59 | 0.38–0.91 | 0.49 | 0.31–0.79 | ||

| 6–19 | 0.71 | 0.45–1.13 | 0.54 | 0.33–0.89 | ||

| 2–5 | 0.67 | 0.44–1.03 | 0.68 | 0.43–1.07 | ||

| 0–1 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Gun show sales, %a | 0.04 | 0.14 | ||||

| ≥25 | 0.61 | 0.33–1.12 | 0.56 | 0.30–1.07 | ||

| >0, <25 | 0.55 | 0.32–0.96 | 0.70 | 0.37–1.33 | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Internet sales, %a | 0.24 | 0.36 | ||||

| ≥10 | 1.25 | 0.78–2.00 | 1.18 | 0.71–1.97 | ||

| >0, <10 | 0.77 | 0.51–1.16 | 0.77 | 0.49–1.21 | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Denied sales, %d | <0.0001 | 0.03 | ||||

| ≥5 | 2.79 | 1.78–4.37 | 1.93 | 1.20–3.11 | ||

| 2–4 | 1.69 | 1.06–2.68 | 1.06 | 0.64–1.74 | ||

| 1 | 1.04 | 0.68–1.58 | 1.24 | 0.78–1.95 | ||

| <1 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Trace requests, %e | 0.057 | 0.53 | ||||

| ≥2 | 1.79 | 1.14–2.82 | 1.21 | 0.75–1.95 | ||

| >0.5, <2 | 1.09 | 0.70–1.70 | 0.85 | 0.53–1.36 | ||

| >0, ≤0.5 | 1.17 | 0.73–1.85 | 1.02 | 0.62–1.68 | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Straw purchase attempts, past year | 0.02 | 0.74 | ||||

| ≥Monthly | 1.83 | 1.04–3.22 | 1.24 | 0.68–2.25 | ||

| >1 or 2 | 2.01 | 1.22–3.30 | 0.85 | 0.50–1.45 | ||

| 1 or 2 | 1.37 | 0.97–1.94 | 1.07 | 0.74–1.55 | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Undocumented purchase attempts, past year | 0.08 | 0.49 | ||||

| ≥Monthly | 1.80 | 1.08–3.01 | 1.04 | 0.51–1.76 | ||

| >1 or 2 | 1.64 | 0.88–3.07 | 0.78 | 0.41–1.50 | ||

| 1 or 2 | 1.09 | 0.76–1.56 | 1.27 | 0.86–1.88 | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Firearm theft, past 5 years | 0.055 | 0.35 | ||||

| Yes | 1.41 | 0.99–2.01 | 0.84 | 0.58–1.22 | ||

| No | Referent | Referent | ||||

Results obtained by ordinal regression. Odds ratios (OR) represent the effect of a given characteristic on the odds of reporting a higher level of support for a comprehensive background check policy (classification: strongly favor > favor > neither favor nor oppose > oppose > strongly oppose) or endorsing a greater number of criteria for denying the purchase of handguns (classification: 9 > 7-8 > 6 or fewer) than was reported by the referent group

aPercentage of overall firearm sales in 2010

bPercentage of handgun sales in 2010

cPercentage of rifle sales in 2010

dPercentage of sales that were denied after a background check, average over 5 years

eAnnual number of trace requests, average over 5 years, as percentage of overall firearm sales in 2010

Many establishment characteristics were positively associated with support for comprehensive background checks, including licensure as a pawnbroker, sales of inexpensive handguns, denied sales, attempted straw purchases, attempted purchases without background checks (p = 0.08), and sales of firearms that were later traced (p = 0.057) (Fig. 1b, Table 1). Sales at gun shows and sales of tactical rifles (p = 0.10) were negatively associated with support for background checks.

In multivariate analysis (Table 2), strong and approximately equal but opposite associations were found with respondents’ agreement that “it is too easy for criminals to get guns” (positively associated) and that “there are too many ‘gun control’ regulations” (negatively associated). Among establishment characteristics, only sales of inexpensive handguns and sales of firearms that were later traced remained statistically significant.

Table 2.

Multivariate associations between respondent and establishment characteristics, support for a comprehensive background check policy, and number of criteria endorsed for denying the purchase of handguns (Variables not listed in the table were not retained in either regression model. See Methods for details of model fitting)

| Characteristic | Comprehensive background check policy | Criteria for denying the purchase of handguns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | p | OR | 95 % CI | p | |

| Respondent characteristics | ||||||

| “It is too easy for criminals to get guns” | <0.0001 | 0.0016 | ||||

| Strongly agree | 5.38 | 2.36–12.25 | 3.97 | 1.60–9.80 | ||

| Agree | 3.58 | 1.60–7.98 | 2.97 | 1.23–7.18 | ||

| Neutral | 1.70 | 0.76–3.81 | 1.75 | 0.72–4.26 | ||

| Disagree | 1.85 | 0.79–4.32 | 1.52 | 0.59–3.91 | ||

| Strongly disagree | Referent | Referent | ||||

| “There are too many gun control regulations” | <0.0001 | |||||

| Very concerned | 0.17 | 0.10–0.30 | ||||

| Somewhat concerned | 0.42 | 0.25–0.70 | ||||

| Not at all concerned | Referent | |||||

| Recommended incarceration for buyer in trafficking operation, years | 0.002 | 0.008 | ||||

| ≥20 | 2.03 | 1.20–3.44 | 2.06 | 1.18–3.62 | ||

| 11–19 | 0.77 | 0.44–1.38 | 1.98 | 1.07–3.66 | ||

| 6–10 | 1.82 | 1.18–2.80 | 1.98 | 1.26–3.09 | ||

| 0–5 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Estimated proportion of retailers who make illegal sales, % | <0.0001 | 0.005 | ||||

| ≥10 | 3.61 | 1.95–6.68 | 1.94 | 1.02–3.70 | ||

| 4–9 | 2.11 | 1.11–3.99 | 1.09 | 0.56–2.12 | ||

| 1–3 | 1.31 | 0.75–2.30 | 0.80 | 0.44–1.45 | ||

| <1 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Establishment characteristics | ||||||

| Handgun sales, %a | 0.10 | |||||

| ≥75 | 0.77 | 0.40–1.48 | ||||

| 50–74 | 1.50 | 0.89–2.51 | ||||

| 25–49 | 0.97 | 0.56–1.70 | ||||

| 0–24 | Referent | |||||

| Inexpensive handgun sales, %b | 0.002 | 0.01 | ||||

| ≥50 | 1.45 | 0.89–2.38 | 1.92 | 1.14–3.24 | ||

| 25–49 | 0.57 | 0.33–1.00 | 0.83 | 0.46–1.50 | ||

| 10–24 | 1.48 | 0.88–2.50 | 0.98 | 0.57–1.69 | ||

| 0–9 | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Trace requests, %c | 0.003 | |||||

| ≥2 | 2.18 | 1.30–3.63 | ||||

| >0.5, <2 | 1.44 | 0.87–2.40 | ||||

| >0, ≤0.5 | 2.44 | 1.43–4.17 | ||||

| 0 | Referent | |||||

Results obtained by ordinal regression. Odds ratios (OR) represent the effect of a given characteristic on the odds of reporting a higher level of support for a comprehensive background check policy (classification: strongly favor > favor > neither favor nor oppose > oppose > strongly oppose) or endorsing a greater number of criteria for denying the purchase of handguns (classification: 9 > 7-8 > 6 or fewer) than was reported by the referent group

aPercentage of overall firearm sales in 2010

bPercentage of handgun sales in 2010

cAnnual number of trace requests, average over 5 years, as percentage of overall firearm sales in 2010

Denial of Handgun Purchase

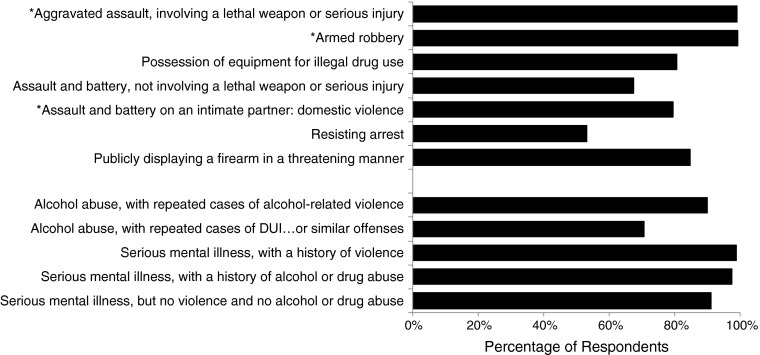

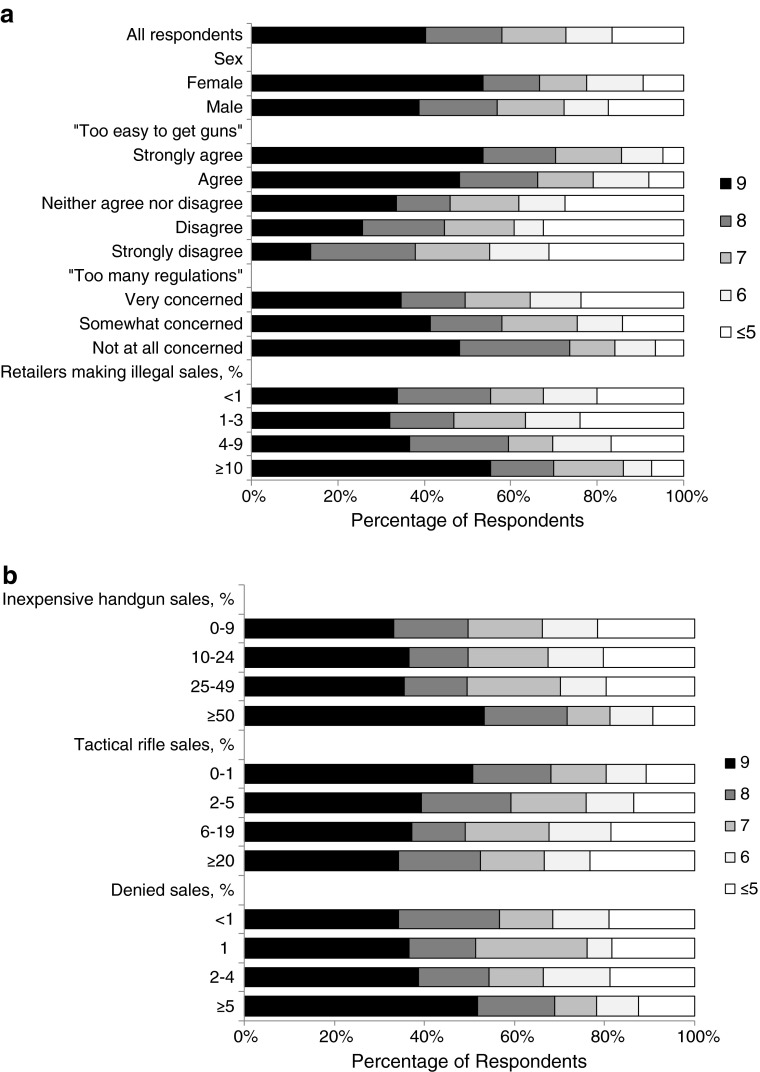

Each of three existing and nine potential criteria for denial of handgun purchase was endorsed by a majority of respondents (Fig. 2); support exceeded 90 % for six criteria and fell below a 2/3 majority for one (resisting arrest). A plurality (40.4 %) of respondents supported all nine new criteria, and an additional 17.5 % supported eight of nine (Fig. 3a).

Figure 2.

Support for denying the purchase of a handgun for selected current and potential criteria based on criminal convictions, alcohol abuse, and serious mental illness. Note: The wording and ordering of the criteria are as in the questionnaire. Those marked with an asterisk (*) exist under current federal law.

Figure 3.

Number of potential denial criteria endorsed (maximum 9). a For all respondents and by sex, agreement with the statements that “it is too easy for criminals to get guns in this country,” concern that “there are too many ‘gun control’ regulations,” and estimated percentage of licensed retailers “who participate knowingly in illegal gun sales.” b By sales of inexpensive handguns and tactical rifles and denied sales. Note: Inexpensive handgun sales are expressed as a percentage of handgun sales, tactical rifle sales as a percentage of rifle sales, and denied sales as a percentage of all firearm sales.

As with comprehensive background checks, support for denial criteria was higher among women and was positively associated with the belief that “it is too easy for criminals to get guns,” the severity of the sentence recommended for an illegal firearm purchaser, and the prevalence of participation in illegal gun sales among retailers (Fig. 3a, Table 1). A concern that “there are too many gun control regulations” was associated with support for fewer criteria, but 49.5 % of respondents who were “very concerned” about regulations endorsed 8 or all 9 of them (Fig. 3a).

Among establishment characteristics, sales of inexpensive handguns and denied sales were associated with support for a greater number of criteria; sales of tactical rifles were associated with support for a lesser number (Fig. 3b, Table 1). In multivariate analysis (Table 2), concern over regulations was not retained; results were otherwise similar to those for comprehensive background checks.

For individual denial criteria (summarized in Table 3, detailed results presented in supplementary material, Appendix Tables 1–4), support was always associated with the belief that “it is too easy for criminals to get guns.” Concern that “there are too many gun control regulations” was in most cases associated with opposition. Sales of tactical rifles were associated with decreased support for denial based on convictions for domestic violence, possession of drug equipment, and assault and battery.

Table 3.

Overview of associations between respondent and establishment characteristics and support for individual criteria for denying the purchase of handguns (see Appendix Tables 1–4 for detailed results)

| Characteristic | Domestic violence | Possessing drug equipment | Assault and battery | Resisting arrest | Displaying a firearm | Alcohol abuse, violence | Alcohol abuse, DUI | Mental illness, no violence or substance abuse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent characteristics | ||||||||

| Age, years (Referent, >65) |

|

|||||||

| Sex (Referent, M) |

|

|

||||||

| “It is too easy for criminals to get guns” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| “There are too many gun control regulations” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Recommended incarceration for buyer in trafficking operation, years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Estimated proportion of retailers who make illegal sales, % |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Establishment characteristics | ||||||||

| Sales in 2010, n |

|

|||||||

| Inexpensive handgun sales, %a |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Sales to law enforcement, %b |

|

|

||||||

| Tactical rifle sales, %c |

|

|

|

|||||

| Gun show sales, %b |

|

|||||||

| Denied sales, %d |

|

|

|

|

||||

Except for age, the referent for quantitative variables is the smallest quantity (e.g., shortest recommended period of incarceration, smallest percentage of denied sales). For “It is too easy” the referent is Strongly Disagree, and for “There are too many” the referent is Not at All Concerned. Symbols appear where p ≤ 0.05, as follows: maximum OR ≥ 2,  ; 1 < maximum OR < 2,

; 1 < maximum OR < 2,  ; 0.5 < minimum OR < 1, ;

; 0.5 < minimum OR < 1, ; ; minimum OR ≤ 0.5,

; minimum OR ≤ 0.5,  . The following variables did not have statistically significant associations with support for any individual denial criterion: concern that “I might sell a gun that gets used in a crime,” licensee type, handgun sales, sales to women, multiple sales, Internet sales, trace requests, straw purchase attempts, undocumented purchase attempts, and firearm theft. More than 97 % of all respondents endorsed denial of purchase based on prior convictions for aggravated assault or armed robbery and for serious mental illness with a history of violence or alcohol or drug abuse. No respondent or establishment characteristics were significantly associated with variations in support for these denial criteria

. The following variables did not have statistically significant associations with support for any individual denial criterion: concern that “I might sell a gun that gets used in a crime,” licensee type, handgun sales, sales to women, multiple sales, Internet sales, trace requests, straw purchase attempts, undocumented purchase attempts, and firearm theft. More than 97 % of all respondents endorsed denial of purchase based on prior convictions for aggravated assault or armed robbery and for serious mental illness with a history of violence or alcohol or drug abuse. No respondent or establishment characteristics were significantly associated with variations in support for these denial criteria

aPercentage of handgun sales in 2010

bPercentage of overall firearm sales in 2010

cPercentage of rifle sales in 2010

dPercentage of sales that were denied after a background check, average over 5 years

Differences by Licensee Type

Support was greater among employees of corporate/multisite licensees than employees of corporate/single site licensees or licensees who were named individual persons for a comprehensive background check requirement (OR 2.65, 95 % CI 1.46–4.81) and for expanded denial criteria (Appendix Table 5).

Discussion

In this survey of federal firearms licensees, respondents supported a comprehensive background check requirement for firearm purchases and an array of criteria for denial of handgun purchase, the latter by wide margins that in some cases approached unanimity. Predictably, support was linked positively to the degree of respondents’ concern over the ease with which criminals acquire firearms and negatively to their concern over the extent of existing firearms regulations.

Support in both areas was associated with many measures of the intensity of respondents’ exposure to illegal activities and with their estimates of the prevalence of participation in illegal sales by other licensees. These associations suggest that retailers are well aware and concerned that prohibited persons, persons with criminal intent, and persons at high risk of committing crimes can readily acquire firearms under current conditions. Retailers have expressed such concerns publicly in the past.33

For example, someone whose purchase from a licensee has been denied following a background check can buy firearms readily, if illegally, from private parties in jurisdictions where private party sales are not subject to a background check requirement. A straw purchase or undocumented purchase that has been thwarted by a responsible licensee can be completed by another who is less conscientious.33–39 In most states, a person with multiple convictions for misdemeanor violent offenses or a sustained history of alcohol abuse can purchase firearms legally.20–22,40

The positive association with sales of traced firearms deserves further comment. Licensees who receive a request for information regarding a firearm that is being traced, generally after its use in a crime, have typically made that firearm’s first retail sale. Approximately 85 % of traced firearms, however, have been recovered from someone other than the first retail purchaser—often years after that first sale is made.41–43 While the intermediate transfers may involve other licensees, as many as 40 % of all firearm transfers involve only private parties.16 Retailers who sell many traced firearms are likely to be aware of these facts and may believe that subsequent transfers of firearms they sell should be subject to the same safeguards that applied to the sales they made.

Sales of large and especially disproportionate numbers of traced firearms identify a retailer as an important point source of firearms used in crime,44–47 and the inference has been drawn that some such retailers are at best negligent and at worst corrupt. The true situation is clearly more complex.

The association with sales of inexpensive handguns may also arise from licensees’ professional knowledge, as such handguns appear with disproportionate frequency among traced firearms, particularly when firearm trafficking is suggested.41,44,48–50 In this study population, increasing sales of these handguns are associated with increasing frequencies of attempted straw purchases and undocumented purchases.24

The reason for the inverse association between sales of tactical rifles and support for comprehensive background checks and some denial criteria is unclear. These firearms are generally believed to pose a special risk to the public’s health and safety and are the target of special regulation. It may be that retailers who frequently sell high-risk firearms are also opposed to restrictions on firearm purchases by high-risk individuals. This remains a subject for further exploration.

The findings here are generally consonant with those of prior survey research29,30,51 and opinion polling52–54 involving firearm owners, including members of the National Rifle Association. These studies have found levels of support for comprehensive background checks ranging from 75 to 85 %, including among firearm owners. The more moderate level of support among our survey respondents may reflect both their concerns about processing additional background checks, particularly if the fees they are allowed to charge are inadequate, and the fact that the survey was conducted prior to recent widely publicized mass shootings. Support for additional denial criteria has been high whenever it has been measured.

Such policies are feasible and effective where they have been enacted. California, for example, denies the purchase and possession of all firearms to persons who have been convicted of misdemeanor offenses involving firearms or violence and requires a background check for essentially all firearm transfers. Even with these additional requirements in place, approximately 600,000 firearms were sold in California in 2011;55 the firearms industry considers the state a “lucrative” market.56 Denying handgun purchases by violent misdemeanants in California reduced their risk of arrest for violent or firearm-related crimes by at least 23 %.12

Limitations

Overall study limitations were reviewed in detail previously in this journal.23 We restricted the study population to licensees with estimated sales above a specific threshold, and licensees from seven states were excluded because the necessary data were not available. Our results cannot be generalized to the entire licensee population. The response rate was comparable to that achieved by others using similar methods for establishment surveys, including the developer of those methods.57,58 There was an effort to interfere with the execution of the survey by the National Rifle Association and the National Shooting Sports Foundation, but this appeared to have little if any effect.23 It is nonetheless possible that subjects who opposed the policy options that were the subject of the survey were less likely than others to respond. Conversely, the lower response rate among employees of corporate/multisite licensees, who expressed much higher levels of support for each policy option, suggests that on balance our results underestimate the level of support for these policies in our study population. Our questions on denial criteria were specific to handguns; support for denial of purchases of rifles and shotguns might be lower.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 812 kb)

Acknowledgments

We are especially grateful to the retailers who participated in the survey, many of whom provided additional helpful comments. Barbara Claire, Vanessa McHenry, and Mona Wright provided expert technical assistance throughout the project. Dr. Tom Smith served as a consultant for the development of the survey questionnaire and gave extensive input. Jeri Bonavia, Kristen Rand, and Josh Sugarmann provided helpful reviews of a draft questionnaire. The Firearm Licensee Survey was supported in part by a grant from The California Wellness Foundation, grant number 2010-067. Initial planning was also supported in part by a grant from the Joyce Foundation, grant number 09-31277.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine, National Research Council. Priorities for research to reduce the threat of firearm-related violence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2013.

- 2.Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2012;61(6):1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed October 25, 2012.

- 4.NCVS Victimization Analysis Tool (NVAT). Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2012. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=nvat. Accessed March 13, 2013.

- 5.Wintemute GJ, Claire BE, McHenry VS, Wright MA. Epidemiology and clinical aspects of stray bullet shootings in the United States. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(1):215–223. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824c3abc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotlowitz A. There are no children here. New York, NY: Doubleday; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozol J. Amazing grace. New York, NY: HarperPerennial; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.18 USC §922(d).

- 9.District of Columbia v Heller, 128, 2783 (SCt 2008).

- 10.McDonald v City of Chicago, 130, 3020 (SCt 2010).

- 11.Frandsen RJ, Naglich D, Lauver GA. Background checks for firearm transfers, 2010—Statistical Tables. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2013. NCJ 238226

- 12.Wintemute GJ, Wright MA, Drake CM, Beaumont JJ. Subsequent criminal activity among violent misdemeanants who seek to purchase handguns: risk factors and effectiveness of denying handgun purchase. JAMA. 2001;285(8):1019–1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright MA, Wintemute GJ, Rivara FA. Effectiveness of denial of handgun purchase to persons believed to be at high risk for firearm violence. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(1):88–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webster DW, Vernick JS, McGinty EE, Alcorn T. Preventing the diversion of guns to criminals through effective firearm sales laws. In: Webster DW, Vernick JS, editors. Reducing gun violence in America: informing policy with evidence and analysis. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013. pp. 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludwig JA, Cook PJ. Homicide and suicide rates associated with implementation of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act. JAMA. 2000;284(5):585–591. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook PJ, Ludwig J. Guns in America: results of a comprehensive national survey on firearms ownership and use. Washington, DC: The Police Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harlow CW. Firearm use by offenders. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2001. NCJ 189369

- 18.Scalia J. Federal firearm offenders, 1992–98. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. NCJ 180795

- 19.Vittes KA, Vernick JS, Webster DW. Legal status and source of offenders’ firearms in states with the least stringent criteria for gun ownership. Inj Prev. 2013;19(1):26–31. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2011-040290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wintemute GJ, Drake CM, Beaumont JJ, Wright MA, Parham CA. Prior misdemeanor convictions as a risk factor for later violent and firearm-related criminal activity among authorized purchasers of handguns. JAMA. 1998;280(24):2083–2087. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.24.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright MA, Wintemute GJ. Felonious or violent criminal activity that prohibits gun ownership among prior purchasers of handguns: incidence and risk factors. J Trauma. 2010;69(4):948–955. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181cb441b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bureau of Justice Statistics. Survey of state procedures related to firearm sales, 2005. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. NCJ 214645

- 23.Wintemute GJ. Characteristics of federally licensed firearms retailers and retail establishments in the United States: initial findings from the Firearms Licensee Survey. J Urban Health. 2012;90(1):1–26. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9754-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wintemute GJ. Frequency of and responses to illegal activity related to commerce in firearms: findings from the Firearms Licensee Survey. Published online ahead of print by Inj Prev, March 11, 2013. doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040715 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. Downloadable lists of Federal Firearms Licensees (FFLs). http://www.atf.gov/about/foia/ffl-list.html. Accessed October 26, 2012.

- 26.SAS for Windows [computer program]. Version 9.1.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2003.

- 27.Dillman D, Smith J. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. 3rd edition ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dillman DA, Gertseva A, Mahon-Haft T. Achieving usability in establishment surveys through the application of visual design principles. J Off Stat. 2005;21(2):183–214. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith TW. Public attitudes towards the regulation of firearms. Chicago, IL: NORC/ University of Chicago; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teret SP, Webster DW, Vernick JS, et al. Support for new policies to regulate firearms: results of two national surveys. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(12):813–818. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Federal Bureau of Investigation. Total NICS background checks. http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/nics/reports/04032012_1998_2012_monthly_yearly_totals.pdf. Accessed November, 2010.

- 32.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. 7th edition. AAPOR; 2011.

- 33.Wintemute GJ. Inside gun shows: what goes on when everybody thinks nobody’s watching. Sacramento, CA: Violence Prevention Research Program; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. Following the gun: enforcing federal laws against firearms traffickers. Washington, DC: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms; 2000.

- 35.Braga AA, Kennedy DM. The illicit acquisition of firearms by youth and juveniles. J Crim Justice. 2001;29(2):379–388. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2352(01)00103-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braga AA, Wintemute GJ, Pierce GL, Cook PJ, Ridgeway G. Interpreting the empirical evidence on illegal gun market dynamics. J Urban Health. 2012;89(5):779–793. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9681-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorenson SB, Vittes K. Buying a handgun for someone else: firearm dealer willingness to sell. Inj Prev. 2003;9(2):147–150. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wintemute GJ. Disproportionate sales of crime guns among licensed handgun retailers in the United States: a case–control study. Inj Prev. 2009;15(5):291–299. doi: 10.1136/ip.2007.017301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wintemute GJ. Firearm retailers’ willingness to participate in an illegal gun purchase. J Urban Health. 2010;87(5):865–878. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9489-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webster DW, Vernick JS. Keeping firearms from drug and alcohol abusers. Inj Prev. 2009;15(6):425–427. doi: 10.1136/ip.2009.023515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. Crime gun trace analysis reports: the illegal youth firearms market in 27 communities. Washington, DC: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, 1999.

- 42.Cook PJ, Braga AA. Comprehensive firearms tracing: strategic and investigative uses of new data on firearms markets. Ariz Law Rev. 2001;43(Summer):277. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wintemute GJ, Romero MP, Wright MA, Grassel KM. The life cycle of crime guns: a description based on guns recovered from young people in California. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43(6):733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wintemute GJ, Cook PJ, Wright MA. Risk factors among handgun retailers for frequent and disproportionate sales of guns used in violent and firearm related crimes. Inj Prev. 2005;11(6):357–363. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.009969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. Commerce in firearms in the United States. Washington, DC: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms; 2000.

- 46.Braga AA, Cook PJ, Kennedy DM, Moore MH. The illegal supply of firearms. In: Tonry M, ed. Crime and justice: a review of research. Vol 29. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 2002: 319–352.

- 47.Pierce GL, Braga AA, Hyatt RRJ, Koper CS. Characteristics and dynamics of illegal firearms markets: implications for a supply-side enforcement strategy. Justice Q. 2004;21(2):391–422. doi: 10.1080/07418820400095851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright MA, Wintemute GJ, Webster DW. Factors affecting a recently-purchased handgun’s risk for use in crime under circumstances that suggest gun trafficking. J Urban Health. 2010;87(3):352–364. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9437-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koper CS. Crime gun risk factors: buyer, seller, firearm, and transaction characteristics associated with gun trafficking and criminal gun use. Philadelphia, PA: Jerry Lee Center of Criminology; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wintemute GJ. Ring of fire: the handgun makers of Southern California. Sacramento, CA: Violence Prevention Research Program; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barry CL, McGinty EE, Vernick JS, Webster DW. After Newtown—public opinion on gun policy and mental illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(12):1077–1081. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Global L. Gun owners poll. New York, NY: Mayors Against Illegal Guns; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Results from a national survey of 1003 registered voters. New York, NY: Mayors Against Illegal Guns; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greenland Quinlan Rosner Research, The Tarrance Group. Americans support common sense measures to cut down on illegal guns. New York, NY: Mayors Against Illegal Guns; 2008

- 55.California Department of Justice. Dealers record of sale transactions. Available at: http://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/pdfs/firearms/forms/dros_chart.pdf? Accessed January 6, 2013.

- 56.Anonymous. California market still lucrative. The New Firearms Business. 2007;14(6):5.

- 57.Paxson MC, Dillman DA, Tarnai J. Improving response to business mail surveys. In: Cox BG, Binder DA, Chinnappa BN, et al., eds. Business survey methods. New York, NY: Wiley; 1995: 303–315.

- 58.Kriauciunas A, Parmigiani A, Rivera-Santos M. Leaving our comfort zone: integrating established practices with unique adaptations to conduct survey-based strategy research in nontraditional contexts. Strat Mgmt J. 2011;32(9):994–1010. doi: 10.1002/smj.921. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 812 kb)