Abstract

Acknowledging the growing disparities in health and health care that exist among immigrant families and minority populations in large urban communities, the UCLA Department of Family Medicine (DFM) sought a leadership role in the development of family medicine training and community-based participatory research (CBPR). Performing CBPR requires that academic medicine departments build sustainable and long-term community partnerships. The authors describe the eight-year (2000–2008) process of building sustainable community partnerships and trust between the UCLA DFM and the Sun Valley community, located in Los Angeles County.

The authors used case studies of three research areas of concentration (asthma, diabetes prevention, and establishing access to primary care) to describe how they established community trust and sustained long-term community research partnerships. In preparing each case study, they used an iterative process to review qualitative data.

Many lessons were common across their research concentration areas. They included the importance of (1) having clear and concrete community benefits, (2) supporting an academic–community champion, (3) political advocacy, (4) partnering with diverse organizations, (5) long-term academic commitment, and (6) medical student involvement. The authors found that establishing a long-term relationship and trust was a prerequisite to successfully initiate CBPR activities that included an asthma school-based screening program, community walking groups, and one of the largest school-based primary care clinics in the United States.

Their eight-year experience in the Sun Valley community underscores how academic–community research partnerships can result in benefits of high value to communities and academic departments.

Disparities in health and health care are national concerns, and our lack of progress in reducing them among racial and ethnic minorities remains a major challenge.1 Underserved minority populations suffer higher rates of premature morbidity, disability, and mortality than does the rest of the U.S. population.2 Many of the determinants of health outcomes are related to social and physical environments as well as the availability of health and social services.3 Those who live in communities with high poverty frequently experience additional adverse social factors related not only to discrimination and economic strain but also to adverse physical environmental conditions, such as air pollution and poor-quality housing.4 For such populations, these factors are often compounded by lack of health insurance and barriers to accessing systems that can provide comprehensive and coordinated primary care. Collectively, these adverse conditions contribute to the persistent health and health care disparities in the United States.

In an effort to address past failures in reducing health disparities, community-based participatory research (CBPR) has been emphasized as a means to improve health outcomes.5 Often, individuals and communities that are the focus of disparities research lack the opportunity to participate actively in the development and outcomes of the projects in which they participate.6 In contrast, CBPR is characterized by developing relationships with organizations and individuals to conduct research to benefit community health in a meaningful and sustainable way. Fundamentally, CBPR (1) is participatory, (2) engages community members and academicians cooperatively and transparently, (3) involves systems development and local community capacity building, (4) is an empowering process for participants, and (5) achieves a balance between research and action.7

Academic medicine departments can use CBPR to improve health outcomes and provide faculty and students with opportunities for community-engaged scholarship. However, academia must build effective long-term research partnerships with communities before undertaking CBPR. To accomplish this, faculty need to understand the processes of community engagement, evaluation of community-based programs, participatory decision making, conflict resolution, and cultural awareness and sensitivity. Academic medical departments, however, need to provide this training for faculty and institutionalize the high value of community-engaged scholarship.8,9 This can help academic medicine departments establish trust and build community capacity. These partnerships can then facilitate a meaningful and successful participatory research process.

In this article, we describe the eight-year process by which the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Department of Family Medicine (DFM) has sustained a high degree of scholarly engagement with an underserved community in Los Angeles County through academic–community partnerships. We describe three case studies of community-partnered and participatory programs that focus on two prevalent diseases and one area for building community capacity: (1) asthma, (2) diabetes prevention, and (3) lack of access to high-quality primary care clinics.

Background

In 1997, Family Medicine at the UCLA School of Medicine achieved department status after almost 25 years as a division. A year later, the mission of Family Medicine expanded to include addressing the health issues of underserved communities in Los Angeles by training family physicians in these settings and recruiting researchers committed to addressing health disparities. As a first step, the department chair (P.T.D.) linked training sites for family medicine residents and medical students to underserved communities that had poor access to care. In late 1999, the DFM expanded its campus-based residency training program to include an off-campus teaching family health center within a Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (LAC-DHS) comprehensive clinic. This new center is part of the Los Angeles health care safety net.

Los Angeles County and Sun Valley

Few areas in the United States are as “health challenged” as Los Angeles County. With a population exceeding 10 million, Los Angeles is our nation’s most populous and most ethnically diverse county.10 Its economy is one of the most vibrant in the world, and there are pockets of great wealth. However, this prosperity is shaded by an increasingly troubling economic paradox, as Los Angeles is now home to the nation’s largest population living in poverty. This is manifested by more than 2.2 million individuals who are uninsured,11 one in six on Medicaid,12 and the largest homeless population in the country—some 80,000. For these individuals and families, Los Angeles can be considered “A Tale of Two Cities.”13 The juxtaposition of want and plenty clearly has health implications. The county’s physician workforce of 25,000 is adequate to care for all; however, access remains a problem for many, as there are approximately 30 federally designated Medically Underserved Areas (MUAs) for primary care within the county.14

One of the UCLA DFM’s community-partnered initiatives is in Sun Valley, a low-income community located five miles east of its teaching clinic in Los Angeles County. This low-income and predominantly Latino community has a significant industrial section that is densely packed with auto dismantling facilities, a large solid waste facility, and many closed rock quarries that are now becoming landfills.15

Partnership evolution

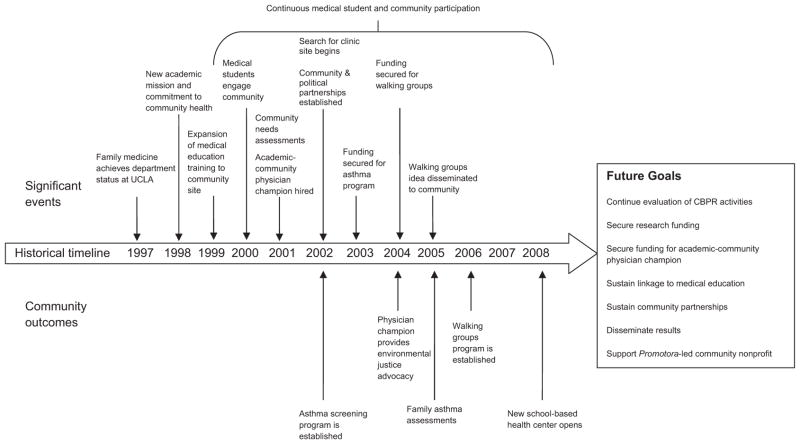

The UCLA DFM upholds its mission and principles to encourage the development of respectful collaboration with communities in research and practice. Leaders encourage faculty members to seek opportunities to work in partnership with communities to ensure that benefits are transparent and significant to both the academician and the community. Because obtaining funding for CBPR is challenging16 and takes time (Figure 1), the DFM started community work by initiating an innovative medical student Summer Urban Preceptorship program to engage underserved communities in Los Angeles County.

Figure 1.

Historical timeline, community outcomes, and future goals of the University of California, Los Angeles Department of Family Medicine–Sun Valley community partnerships, Los Angeles County, California, 2000–2008.

In the summer of 2000, the DFM recruited a group of six first-year UCLA medical students who had expressed interest in community medicine for a Summer Urban Preceptorship program. The dean’s office provided stipend support, and the summer program was organized and structured to include a series of selected readings, didactic and discussion sessions, and a community group project. Students selected a project that focused on collecting data about the distribution of physicians in low-income communities of the San Fernando Valley. They prepared and submitted an application to the federal government that led to the area being designated as a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) for primary care. With this designation, health professionals who elect to practice in the area receive loan repayment benefits as well as enhanced Medicare physician payments.

In the summer of 2001, the DFM once again sponsored its Summer Urban Preceptorship for UCLA medical students who participated in a project that involved a random cluster needs assessment survey of households in the Sun Valley area. The medical students received instruction on survey sampling and design methods and on how to perform a health interview. They obtained IRB approval and conducted door-to-door surveys of more than 300 randomly selected households and achieved a participation rate of over 85%. The medical students presented preliminary results to colleagues and the local state legislator.

Medical student involvement from 2002 to 2008 continued to enable the DFM to establish a relationship with community organizations and key stakeholders. Table 1 describes the main partners of our community-based partnered and participatory initiatives. After many years, the medical student community projects eventually evolved into partnered and participatory community-engaged scholarship and research.

Table 1.

Description of University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Department of Family Medicine (DFM)–Sun Valley Community Partnerships, 1999–2008

| Partner organization* | Description of partnership |

|---|---|

| Sun Valley Middle School (SVMS) | Open year-round for approximately 3,000 students from the community, grades six through eight. SVMS first partnered with UCLA DFM in 2001 during the medical student community needs assessment survey. |

| Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) | LAUSD is the second-largest and among the most diverse in the country with a K–12 enrollment of almost 700,000 students. Seventy-three percent of students are Latino, and 11% are black, with whites, Asians, Native Americans, and Pacific Islanders making up the remaining ethnic/racial groups.† The district administers many school-based health programs throughout Los Angeles County. |

| Los Angeles County Department of Health Services (LAC-DHS) | LAC DHS is the major provider of health services for approximately two million uninsured people. It is the second-largest county health system in the nation and is overseen by the five members of the County Board of Supervisors. |

| Faith-based community group | The Holy Rosary Catholic Church in Sun Valley is a vibrant community church with over 4,000 parishioners and a priest who is known for his community activism. In addition, the regional Catholic nurse ministries have taken an active, supportive role in promoting the screening of the population for diabetes and referring those found to have diabetes or prediabetes to the UCLA walking groups program in Sun Valley. |

| Local rotary club | The Sun Valley Rotary Club played a key role by providing input during planning of community research projects. They also provided the funding to create incentives for community members that participated in the walking groups. |

| Local political stakeholders (e.g., city council member) | Local city councilman and local County Board of Supervisors representatives were key in the formation of a partnership among the LAC-DHS, the LAUSD, and the UCLA DFM as well as obtaining state funding for a health center on the grounds of the SVMC. The local city councilman’s office also covered the cost of T-shirts as incentives for the walking groups program participants. |

| Sun Valley parent groups | Parent groups are part of each school and represent a social unit within the area. Each public school, including SVMS and its “feeder” elementary schools, has a “Parent Center” from which a dedicated group of parents support the school and community health efforts. |

| North East Valley Health Corporation | North East Valley Health Corporation is a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) organization that entered into an agreement with the above entities to operate the new community health center. |

Partners played a major role in one or more partnered/participatory projects at some point in the eight-year process of the UCLA DFM initiatives. Community engagement began in the Sun Valley community in 1999–2000.

Source: Los Angeles Unified School District. District and Local Profile. Los Angeles, Calif. Available at: (http://notebook.lausd.net/portal/page?_pageid=33,48254&_dad=ptl&_schema=PTL_EP). Accessed July 6, 2009.

We present case studies of the three research concentration areas (a school-based asthma screening program, walking groups to prevent diabetes, and a new community clinic providing access to primary care) and an overview of how we sustained partnerships and built community trust. To prepare each case study, we used an iterative process to examine qualitative program data corresponding to meeting notes and minutes, grant proposals, reports, scientific meeting presentations, and works in progress presented within the department and medical school. The authors have historical insight into the community-partnered activities and provided rich detail. Each case study is unique and illustrates a different degree of community partnership and participation (Table 2). Furthermore, we provide a brief overview of our preliminary results to date and how we disseminated these results to the community. Finally, we identified key lessons that were important to at least two of the three community-partnered projects. Table 3 describes the specific roles of community and academic partners by community partnered/participatory initiatives.

Table 2.

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)–Sun Valley Partnered and Participatory Research Priority Areas and Participating Community Partners by Degree of Community Participation

| Community research priority areas | Academic partner

|

Public and community partners

|

Degree of participation† | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCLA DFM* | LAUSD* | LAC-DHS* | LAC CHC* | Rotary club | Faith-based group* | Parent groups | Local political office(s)* | ||

| Asthma screening | X | X | X | X | Moderate | ||||

|

| |||||||||

| Diabetes prevention (walking groups) | X | X | X | X | X | High | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Access to new primary care clinic | X | X | X | X | X | X | Low | ||

UCLA DFM indicates University of California, Los Angeles Department of Family Medicine; LAUSD, Los Angeles Unified School District; LAC-DHS, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services; LAC CHC, Los Angeles County Community Health Coalition; faith-based group, local Catholic church and regional Catholic nurse ministries; local political office(s), Los Angeles City Council and Los Angeles County Supervisors Office.

Degree of community participation based on fundamentals of community-based participatory research. Source: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2003.

Table 3.

The Role of Community and Academic Partners by Community Partnered/Participatory Initiative for the University of California, Los Angeles–Sun Valley Community Partnerships, Los Angeles County, California

| Community partner | Community initiative | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Walking groups | Asthma program | Access to primary care | |

| Sun Valley Middle School |

|

|

|

| Los Angeles Unified School District |

|

|

|

| Los Angeles County Department of Health Services |

|

|

|

| Faith-based community group |

|

|

|

| Local rotary club |

|

|

|

| Local political stakeholders (e.g., city council member) |

|

|

|

| Sun Valley parent groups |

|

|

|

| North East Valley Health Corporation |

|

|

|

| University of California, Los Angeles Department of Family Medicine |

|

|

|

Case Study: School-Based Asthma Screening Program

In Los Angeles, children with asthma more frequently miss school than those without asthma.17 This excessive absenteeism may jeopardize student performance18,19 and represents a threat to the financial viability of public schools that obtain funding based on attendance. As such, schools have great interest in efforts to prevent or ameliorate asthma’s effects on students.

The results from the 2001 community needs assessment, conducted by medical students, identified asthma as a major concern for community members. After we shared the results of our needs assessment with them, leaders from Sun Valley Middle School (SVMS) and the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) supported and encouraged efforts to develop and implement a community asthma intervention. The DFM respected the community’s concern and priorities and hired an academic–community champion physician (G.A.L.) to develop the asthma project in late 2002. The chair hired a physician with a masters of public health degree and extensive community medicine experience in the United States and Guatemala. Seventy percent of the champion physician’s time was protected and dedicated to facilitating academic–community engagement and directing health programs in Sun Valley.

We encountered many challenges to establishing an asthma program. First, funding within the DFM is limited and cannot support such a long-term project with a long research to translation period. Ultimately, we obtained a grant from a local foundation to begin the Sun Valley Asthma Screening and Early Intervention Program and hired staff from the community. SVMS housed the program in a building near the physical education area of the campus. We then began to design an educational curriculum from published materials and the responses we received when we screened children.

Another challenge was learning how to coexist and negotiate insider–outsider tensions20 with existing nonprofit community organizations in Sun Valley. We were able to address this potential conflict by finding a mutually beneficial research agenda. A local organization that was active in asthma treatment in elementary schools throughout the county had reservations about the treatment component of our program. We held meetings with SVMS and sought the support of the local politicians who were familiar with our community assessment findings. Because we had community assessment data and the support of the community, we were able to negotiate at every table. Specifically, we mounted an informational campaign in LAUSD administrative offices. Four months of negotiations resulted in a compromise: We reinstated only the screening portion of our program and not the early treatment component.

Every year, approximately 1,000 families receive letters requesting parents’ consent to enroll their children in the asthma program. The participation rate is consistently between 52% and 58%. Enrolled children complete a 13-item oral questionnaire during their physical exercise class about asthma symptoms and related exposures such as cigarette smoke. Those with a positive screen are evaluated by the program medical director who determines if referrals or treatment are needed.

Even the families who do not participate but receive information through the mail are aware of our work in the community. Many parents mention that they are familiar with UCLA’s asthma program because of the school-based awareness efforts. In addition, efforts to promote walking groups (discussed below) at the large local catholic church have resulted in members approaching UCLA staff and asking whether the walking groups are part of the asthma program.

One outcome of the community-partnered asthma screening program is an innovative comprehensive “family session” intervention for students identified as having asthma. The intervention identifies and addresses environmental and social factors contributing to asthma-related health. The family sessions are showing impressive outcomes with respect to subsequent asthma diagnosis and treatment. An evaluation of the first 102 family sessions showed that by four months after the family session, 60% of the students with undiagnosed and/or uncontrolled asthma were well controlled using National Institutes of Health criteria for asthma care (unpublished data).

The fact that we were limited to screening the students without directly providing treatment actually allowed for the development of a sustainable and replicable program. Having a physician on-site to diagnose and treat all children with asthma as we originally intended is not a replicable model. However, screening students for asthma, alerting their parents to their condition, and supporting the parents in their attempts to secure quality health care is a viable and effective venture. Because it is not uncommon for asthma to be underdiagnosed,21,22 we plan to examine various permutations of the asthma screening process to identify the most sustainable approach that yields tangible benefits for the community.

We shared the results of the asthma program with the community through the local monthly public Sun Valley Neighborhood Council and Bradley Landfill Advisory Committee meetings. We also presented findings to LAUSD and to the LAC-DHS’s Childhood Asthma Collaborative.

Case Study: Community Walking Groups

Each child we screen for asthma is measured for height and weight. The results of our 3,500 child screens show that two thirds of the children are overweight and half are obese (BMI >94%) (unpublished data). This finding, coupled with the high and growing prevalence of diabetes among Latinos in Los Angeles County,23 helped to focus attention on a need for the development of a community-based participatory intervention that would encourage families to participate in daily physical activity. Parents would serve as role models by walking with their children. Our academic–community champion physician conceived the concept and widely disseminated the idea for input among different community stakeholders, local politicians, and community members. First, we held three focus groups of 10 to 12 community members at the SVMS Parent Center to explore community perceptions of walking groups. Then, we interviewed 200 Sun Valley families, selected in a representative fashion, regarding their exercise habits and views toward the walking group concept. This proved to be a popular idea among the Latino adults, with 83% noting their interest in participating. We also sought input from local religious leaders, politicians, and the Sun Valley Rotary Club (unpublished data). Ultimately, this resulted in the establishment of the Sun Valley Saludable–Healthy Sun Valley program that is now in its fourth year of operation.

The program was replicated throughout the community and established a total of 14 “walking groups” which operate from Monday through Friday for one hour, each in different locations and at different times. In our first year, we had 1,604 participants, 40% of them children. These groups have continued to grow during the second year with little formal promotion beyond the participants themselves wearing bright yellow program T-shirts made with donations from community partners. To date, over 4,000 Sun Valley residents have participated in the walking groups.

The success in replicating the walking groups is partly due to promotoras who educate families on healthier lifestyles and chronic disease. Promotoras are lay health care professionals (from the community) who understand community issues and serve as connectors between community members and health professionals. They are actively involved in the implementation and evaluation of this project. According to the promotoras, participants are motivated to walk because they find social support to deal with problems such as alcoholism, family violence, depression, and diabetes (unpublished data). Another reason they participate is their familiarity with UCLA’s presence in SVMS and in the local catholic churches.

The DFM has disseminated the idea for walking groups throughout the greater Los Angeles area. The Univision Communications, Inc., local Spanish-language television affiliate aired, on several occasions, coverage of the participants as well as a two-month public service announcement in support of community-based walking with contact information for the DFM. Other local television stations and newspapers have covered the social change occurring in the community as a result of this project.

Case Study: Sun Valley Community Clinic

The needs assessment done by medical students in 2001 showed that access to affordable, high-quality medical care was a major community concern. Based on this, the DFM elected to spearhead the establishment of a community health center by establishing a partnership with the school district (LAUSD). Eventually, the LAUSD donated the use of land on the campus of SVMS to build the community health center. Furthermore, we formed partnerships with the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors to secure the funding for the building of the facility. LAC-DHS provides partial funding for the continuing costs of running the clinic.

Identifying the funding and a location for the needed clinic required a solid relationship with local political stakeholders. We also sought community input through public hearings. In one hearing, some community members expressed concerns about having a county-run clinic that would attract “drug addicts” and homeless people and depreciate the value of neighborhood homes. Others, however, acknowledged the need for access to safety-net medical care and suggested SVMS as a location. Unlike the community, UCLA envisioned a clinic in a residential area but addressed community concerns by locating the clinic in SVMS.

The recently inaugurated Sun Valley Health Center (part of Northeast Valley Health Corporation), one of the largest school-based community clinics in the nation, finally opened in April 2008. The clinic provides services for students and for the entire community.

Lessons Learned

By examining these case studies, we identified six key lessons learned that are central to CBPR and are critical in sustaining community partnerships and trust. We list these lessons below to illustrate their significance in our community-partnered initiatives.

Academic–community champions

Key to sustaining our community–academic partnerships was a physician community champion who made large contributions to the community. He was able to serve as a spokesperson for the DFM as well as, after gaining community trust, an advocate for the Sun Valley community on issues ranging from child health to environmental justice. Securing funding for our community–academic physician champion was essential to the viability of our partnered efforts in Sun Valley. He receives full funding from the DFM. Additional funding to support programs, staff, and research was obtained through foundation grants.

Long-term academic commitment

The DFM chair’s clear commitment was essential in developing and maintaining the community trust that set the stage for CBPR for eight years. The dedicated annual financial support from the medical school dean’s office was also instrumental for medical student community-engaged scholarship.

We plan to seek support from the DFM and school of medicine to help connect graduate medical education with ongoing community projects. Because residency training in social and community medicine is associated with practice-based outcomes,24 we aim to promote resident physician involvement in longitudinal community projects. Currently, residents interested in community medicine are encouraged to meet with our academic–community champion physician and research faculty (M.A.R.) to incorporate experiential community training into their graduate medical education.

Clear and concrete community benefits

Community partners need to experience concrete results from the partnerships. The long process of CBPR requires transparent and flexible research goals with clear community benefits.

Political advocacy

Obtaining buy-in from local political stakeholders is important in CBPR. In our experience, developing a relationship with the local councilman and county supervisor was a long-term but essential process for large community interventions.

The local Los Angeles City councilman invited the academic–community champion physician to be part of an advisory committee that advises him about community concerns regarding a large nearby landfill. Environmental justice issues are important to area residents because of the possible environmental exposures from the area’s heavy industry. Therefore, the DFM works with the councilman’s office as a voice for the community. As such, the councilman and his office have been most supportive of the asthma-screening program and other UCLA community-wide participatory efforts.

Partnerships with diverse organizations

Creating partnerships with established community organizations is crucial in maintaining long-term research partnerships. Small community organizations should be involved in the research process as well. However, including established partner organizations with a high likelihood of longevity also helps ensure sustainability of community partnerships.

Medical student participation

Medical students participate in Sun Valley community research on a yearly basis and contribute to an inflow of new ideas. They provide a workforce that facilitates the administration and collection of community programs data. The DFM offers students who are not interested in conducting basic science or bench research an opportunity to become involved in community-based research. Students, however, also have the option of analyzing secondary data from the community with the guidance of senior research faculty. Medical students are evaluated on the basis of participation in seminars, in the field, and final scholarly presentation during UCLA’s summer research fair.

Discussion

The DFM continues to seek the advancement of partnered and participatory research activities in Sun Valley and other communities. We learned many lessons and continue to move forward from partnered community programs to participatory research. In aggregate, it is precisely the nurtured strong community ties that distinguish this community partnership, built from a person-by-person or family-by-family intervention that honors the community’s view of health priorities and addresses them alongside our own program agendas. Because the DFM and all involved with these projects are also affected by the community members’ successes and challenges, we are motivated to develop further programs, and we are able to learn from the experiences acquired while enjoying the benefits of being part of such a vibrant and resourceful community. One of the authors (G.M.) participated as a medical student and was motivated to seek advanced CBPR training in the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars program.25 Overall, UCLA faculty has gained better insight on the benefits of continuity in working with communities.

Within our experience are many implications for other academic departments of medicine. It takes a long time for community research to yield concrete results, and our lessons learned in almost a decade of sustaining a high level of community engagement may inform other departments seeking to develop community programs. Furthermore, our partnered projects provide an important opportunity for medical students and residents to become involved with partnered and participatory projects and learn about community medicine. Students learn the process of conducting scholarly community research with the active participation of community members. They actively engage with community promotoras, our academic–community champion physician, and local policy stakeholders. We also offer community medicine rotations for family medicine residents and elective clerkships for UCLA and Charles R. Drew University medical students. Many of the participating students are from underserved communities themselves. Overall, experiences for students and faculty have been positive and have contributed greatly to the sustainability of our partnerships.

Our experience demonstrates that it is possible for academic medicine departments to sustain long-term scholarly community engagement and generate innovative products that build community capacity. The high value of our programs to the community may help ensure sustainability despite financial challenges. For example, funding is coming to an end for the promotoras in our walking groups, but the promotoras have begun the planning phase of a new community nonprofit organization that will focus on the health needs of Sun Valley and sustaining the walking groups.

It is important to highlight the significance of data collection for our community research projects. Participants learn about ethical issues (i.e., randomization) and limitations of data collection in underserved communities. Not only does data collection provide a scholarly community-research experience for students, faculty, and community, but it also helps inform and shape programs. The formative research data collected from our asthma screenings were needed to conceive our community walking groups program. Subsequently, the focus group, family survey, and community stakeholder data were essential to the design of the walking groups.

Looking ahead, we plan to study the effect of the asthma screening program and family intervention sessions on intermediate outcomes for asthma (emergency department visits, hospitalizations, frequency and severity of symptoms, and use of controller medications) and quality of life.26 Our control group will receive standard asthma care from their primary care providers. We are also currently conducting a small pilot weight-loss intervention for participants in the walking groups. Promotoras and medical students have collected baseline data from 98 participants. We aim to determine the effect of weekly weighing versus no weighing on participant weight loss and walking group attendance. In addition, we will explore how community walking is related to participants’ depression scores.

After nearly a decade of community-partnered and community-participatory initiatives involving a needs assessment, HPSA and MUA community designation, school-based asthma screening, a community walking groups project, and a new comprehensive primary care clinic, the community trusts the UCLA DFM enough to join in participatory research. This collaboration only occurred after we earned the community’s overall trust and demonstrated we could provide a concrete service that they needed and valued: access to affordable, high-quality primary care for all children and families in the community.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the important contributions of community members and partners who participated in the projects described in this manuscript. Funding support for Dr. Moreno was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Rodriguez was supported by UCLA/DREW Project EXPORT, NCMHD, P20MD000148/P20MD000182, and the Network for Multicultural Research on Health and Healthcare, Department of Family Medicine–UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The authors would like to thank Kenneth Wells and Elizabeth Esparza-Cervantes for comments on an early draft of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dr. Gerardo Moreno, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars Program, and clinical instructor, Department of Family Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

Dr. Michael A. Rodríguez, Department of Family Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

Dr. Glenn A. Lopez, Department of Family Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

Dr. Michelle A. Bholat, Department of Family Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

Dr. Patrick T. Dowling, Department of Family Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California.

References

- 1.Beach MC, Cooper LA, Robinson KA, et al. Strategies for Improving Minority Healthcare Quality. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Jan, 2004. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galea S, Vlahov D. Urban health: Evidence, challenges, and directions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:341–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;(Spec No):80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faridi Z, Grunbaum JA, Gray BS, Franks A, Simoes E. Community-based participatory research: Necessary next steps. [Accessed June 25, 2009];Prev Chronic Dis [serial online] 2007 Jul; Available at: ( http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2007/jul/06_0182.htm) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Green LW, Mercer S. Can public health researchers and agencies reconcile the push from funding bodies and the pull from communities? Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1926–1929. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michener JL, Yaggy S, Lyn M, et al. Improving the health of the community: Duke’s experience with community engagement. Acad Med. 2008;83:408–413. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181668450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steiner BD, Calleson DC, Curtis P, Goldstein AO, Denham A. Recognizing the value of community involvement by AHC faculty: A case study. Acad Med. 2005;80:322–326. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. [Accessed June 25, 2009];Population estimates for the 100 largest US counties based on July 1, 2007 population estimates: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2007 (CO-EST2007-07) Available at: ( http://www.census.gov/popest/counties/CO-EST2007-07.html)

- 11.Brown ER, Lavarreda SA, Ponce N, Yoon J, Cummings J, Rice T. The State of Health Insurance in California: Findings From the 2005 California Health Interview Survey. Los Angeles, Calif: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown ER, Lavarreda SA, Rice T, Kincheloe JR, Gatchall MS. The State of Health Insurance in California: Findings From the 2003 California Health Interview Survey. Los Angeles, Calif: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Executive Summary of the State of Los Angeles County. Los Angeles, Calif: United Way of Greater Los Angeles; 2003. A Tale of Two Cities: Bridging the Gap Between Promise and Peril. [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Department of Human and Health Services. Health Resources and Services Administration. [Accessed June 25, 2009];Find shortage areas: MUA/P by state and county [database online] Available at: ( http://muafind.hrsa.gov/index.aspx)

- 15.California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. [Accessed June 25, 2009];California Healthcare Workforce Catalog. Available at: ( http://gis.ca.gov/catalog/BrowseCatalog.epl?id=1044)

- 16.Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: Implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health. 2003;8:1210–1213. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonilla S, Kehl S, Kwong KY, Morphew T, Kachru R, Jones CA. School absenteeism in children with asthma in a los angeles inner city school. Pediatrics. 2005;147:802–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moonie S, Sterling DA, Figgs LW, Castro M. The relationship between school absence, academic performance, and asthma status. J Sch Health. 2008;78:140–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taras H, Potts-Datema W. Childhood asthma and student performance at school. J Sch Health. 2005;75:296–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minkler M. Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health. 2005;85(2 suppl):ii3–ii11. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helms PJ. Issues and unmet needs in pediatric asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;30:159–165. doi: 10.1002/1099-0496(200008)30:2<159::aid-ppul14>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joseph CL, Foxman B, Leickly FE, Peterson E, Ownby D. Prevalence of possible undiagnosed asthma and associated morbidity among urban schoolchildren. J Pediatrics. 1996;129:735–742. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diamant AL, Babey SH, Brown ER, Hastert TA. Diabetes on the Rise in California. Los Angeles, Calif: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strelnick AH, Swiderski D, Fornari A, et al. The residency program in social medicine of Montefiore Medical Center: 37 years of mission-driven, interdisciplinary training in primary care, population health, and social medicine. Acad Med. 2008;83:378–389. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816684a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voelker R. Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars mark 35 years of health services research. JAMA. 2007;297:2571–2573. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.23.2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Gent R, van Essen-Zandvliet EE, Klijn P, Brackel HJ, Kimpen JL, van Der Ent CK. Participation in daily life of children with asthma. J Asthma. 2008;45:807–813. doi: 10.1080/02770900802311477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]