Abstract

Recently published guidelines suggest that the most opportune time to treat individuals with Alzheimer’s disease is during the preclinical phase of the disease. This is a phase when individuals are defined as clinically normal but exhibit evidence of amyloidosis, neurodegeneration and subtle cognitive/behavioral decline. While our standard cognitive tests are useful for detecting cognitive decline at the stage of mild cognitive impairment, they were not designed for detecting the subtle cognitive variations associated with this biomarker stage of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. However, neuropsychologists are attempting to meet this challenge by designing newer cognitive measures and questionnaires derived from translational efforts in neuroimaging, cognitive neuroscience and clinical/experimental neuropsychology. This review is a selective summary of several novel, potentially promising, approaches that are being explored for detecting early cognitive evidence of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease in presymptomatic individuals.

Introduction

Over the next 30 years, more than 20 million Americans are at risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia and there is no effective disease-modifying treatment. Recently published guidelines suggest that the best time to intervene in AD might be during a preclinical phase [1], when the underlying pathophysiological changes are occurring up to 15 years in advance of clinical symptoms [2]. With the advent of in vivo amyloid imaging, approximately 20 to 30% of all cognitively normal older individuals harbor a significant burden of amyloid pathology, a hallmark of AD [3-6], and these individuals are now the target population for planned secondary prevention trials in the treatment of AD [7].

As these treatment trials are being contemplated, they will focus on recruiting individuals who have no detectable cognitive impairment on our standardized instruments but instead display biomarker evidence as being at risk for progressing to AD dementia. AD treatment trials in the past have used cognitive tests and questionnaires that may not be optimal for these currently planned studies, which are aimed at detecting subtle cognitive changes in clinically normal individuals and reliably tracking treatment change over time. The field has therefore been challenged to modify and improve the sensitivity of our current standardized tests through the use of sophisticated psychometric techniques or to develop a new generation of cognitive instruments and questionnaires that can be used in these prevention trials.

Cognitive and behavioral assessments have long been considered the gold standard for the diagnosis and prediction of AD progression. However, numerous studies have failed to find a relationship between cognitive performance and biomarker evidence of AD in clinically asymptomatic at-risk individuals [8-11]. In part, the relationship between early amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposition and performance on traditional standardized cognitive tests was found to be influenced by cognitive reserve (CR) [12-16]. The concept of CR was initially introduced as a possible explanation for the delayed onset of dementia among individuals who had high occupational or educational attainment. One theory is that those with high CR may tolerate AD pathology for longer before demonstrating declines on cognitive testing [17], and thus may interfere with our ability to detect subtle cognitive changes thought to be associated with preclinical AD [1]. Therefore, as we develop tests sensitive to the early cognitive changes associated with biomarker evidence of preclinical AD, we will need to use better approaches for measuring CR or our new tests will need to take into account age, education, sex and race/ethnicity effects on performance, all of which will provide some relative anchoring of an individual’s performance vis-à-vis CR.

Ultimately, these newly developed measures will need to be simple, cost-effective, and capable of capturing the subtle changes that can differentiate healthy aging from preclinical AD. These tests also need to be useful across all ethnicities and educational strata as well as proving sensitive to change over the short timeframe of a clinical trial. Given the significant advances made toward the in vivo detection of biomarkers in preclinical AD (that is, amyloid imaging, cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) amyloid/tau, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) volume loss) [6,18,19], a recent meta-analysis indicated that early amyloid pathology, a biomarker of preclinical AD, appears to have a greater influence on memory-related systems [20] in clinically normal older adults than other cognitive domains. The authors therefore selected the instruments presented here because they were essentially tests of memory that were derived from knowledge gained through these translational efforts in neuroimaging, neuroscience, and clinical and experimental neuropsychology. The instruments were also designed to target the neural pathways involved in the basic components of memory including encoding (that is, learning of new information), retrieval (that is, accessing information) and storage (that is, recognition of information), as well as additional features including associative binding, semantic encoding, pattern separation and spatial discrimination that may be vulnerable in preclinical AD cohorts. We included tests of executive function because the meta-analysis suggested that these tests [20] also had a significant although weaker association with amyloid deposition than episodic memory. No other cognitive domains were related to biomarker evidence of preclinical AD. Finally, we have included a section on patient-oriented outcome measures related to subjective cognitive concerns because there is recent interest in and support for these very early complaints in clinically normal individuals perhaps also heralding evidence of preclinical AD and risk of subsequent cognitive decline.

Hence, the overall goal of this article is to present a selective summary of just some of the newer, potentially promising approaches for detecting cognitive evidence of preclinical AD in presymptomatic individuals (see Table 1). Presenting an exhaustive list of all tests and measures that have demonstrated the ability to detect cognitive decline at the stage of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is beyond the scope of this review, but rather we select a few tests/questionnaires that have shown promise for having an association with biomarker evidence of preclinical AD. Some of these tests were developed recently, and therefore are not fully validated, and some are unpublished. However, these tests are included here because they show promise in targeting neural pathways that might be useful in early detection studies.

Table 1.

Tests showing sensitivity to subtle cognitive changes associated with biomarker evidence of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease

| Test | Memory component | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Capacity Test [13] |

Verbal associative binding |

34 HC, decrements in second-list learning associated with amyloid burden |

| Face Name Associative Memory Exam (FNAME) [22,31] |

Cross-model associative binding |

45 HC, decrements in face name versus face occupation associated with amyloid burden |

| |

|

210 HC, good test–retest and discriminate validity for name, occupation and summary scores, useful across all educational strata |

| |

|

129 HC, FNAME performance summary scores were associated with reduced hippocampal volume and APOE4 carrier status |

| Short-Term Memory Binding test [41] |

Visual recognition, change detection, feature binding |

30 asymptomatic carriers with E280A mutation showed impairment in visual short-term memory binding, suggesting short-term memory binding may be a preclinical marker for familial AD |

| Behavioral Pattern Separation-Object test [49,50] |

Visual recognition, pattern separation |

31 HC, impairments in pattern separation were noted in those with weaker RAVLT Delayed Recall Scores. Recognition Memory was normal. In 23 aMCI individuals, pattern separation deficits improved in those exposed to drug treatment during a clinical trial |

| Spatial Pattern Separation task [51,56] |

Visual recognition, pattern separation, spatial discrimination |

37 HC, Spatial Pattern Separation performance was associated with reduced bilateral hippocampal volume and with the CSF Aβ42/pTau181 ratio. Paragraph recall was not sensitive to these biomarker correlates |

| Discrimination and Transfer task [62,63] |

Spatial discrimination |

37 HC, reduced transfer performance was associated with mild-to-moderate hippocampal atrophy in CN and associated with clinical impairment 2 years later. Performance also correlated with CSF Aβ42 and the Aβ42/pTau181 ratio |

| Dual tasking task [76,77] | Spatial discrimination | 39 E280A mutation carriers showed dual tasking impairments despite normal performances on other standard neuropsychological tests of cognition and memory. Dual tasking performance discriminates asymptomatic carriers with familial AD from healthy controls |

Aβ, amyloid beta; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; aMCI, amnestic mild cognitive impairment; APOE4, apolipoprotein E4; CN, cognitively normal; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HC, healthy older controls; RAVLT, Rey auditory verbal learning test.

Tests of memory associated with evidence of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease

Memory Capacity Test

The Memory Capacity Test from Herman Buschke was recently published as showing sensitivity to Aβ deposition on amyloid imaging in normal older adults [13]. Similar to the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, the Memory Capacity Test improves encoding specificity by means of pairing the word to be remembered with a category/semantic cue [21], inducing deep semantic encoding to maximize learning and retrieval.

The Memory Capacity Test uses two 16-item word lists (32 pairs) to be remembered from the same category cues as the first list. The test measures associative binding with the objective that decrements in the second-list recall would be more sensitive to the early pathological changes associated with preclinical AD. In fact, individuals with greater Aβ burden on amyloid imaging showed normal recall on the first list but lower than normal binding scores on the second list despite performing normally on other standardized tests of memory [13].

Tests that challenge the associative binding system, such as the Memory Capacity Test, show promise for being able to distinguish older adults in the preclinical phase of AD.

Face Name Associative Memory Exam

The Face Name Associative Memory Exam (FNAME) [22] is a cross-modal associative memory test based on a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) task that pairs pictures of unfamiliar faces with common first names. Previous fMRI work from multiple groups has suggested that the successful formation and retrieval of face–name pairs requires the coordinated activity of a distributed memory network [23-25]. This network includes not only the hippocampus and related structures in the medial temporal lobe, but a distributed set of cortical regions, collectively known as the default mode network [26]. The face–name fMRI task has shown sensitivity to longitudinal clinical decline in MCI [27] as well as in those at genetic risk for AD [23,28,29], and is associated with Aβ burden in clinically normal older individuals [30].

The FNAME is a short behavioral version of the fMRI task that requires the individual to remember 16 unfamiliar face–name pairs and 16 face–occupation pairs, for a total of 32 cross-modal paired associates to be remembered (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Example of Face Name Associative Memory Exam stimuli.

The distribution of scores on the FNAME in clinically normal adults did not exhibit the same ceiling effects, in contrast to other standardized tests of memory in this asymptomatic cohort [22], and is useful over a range of education and CR. Performance for face–names as well as a summary score of names and occupations showed good test–retest reliability [31] and was correlated with Aβ burden on amyloid imaging [22], reduced hippocampal volume on MRI, as well as APOE4 carrier status in cognitively normal older adults [32]. A simpler 12-item version of the FNAME was developed for face–name pairs only, similar to the original fMRI task. A computerized version of the FNAME is being developed on the iPad (Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA) in conjunction with CogState® (Cogstate Ltd, Melbourne, Australia) and will be used as a secondary outcome measure in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network and the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic AD secondary prevention trials, purposely designed to treat presymptomatic individuals at risk for AD. Further validation work is being done to determine whether this alternate version of the FNAME will be useful for measuring clinical change over the course of a clinical trial in asymptomatic individuals at risk for AD.

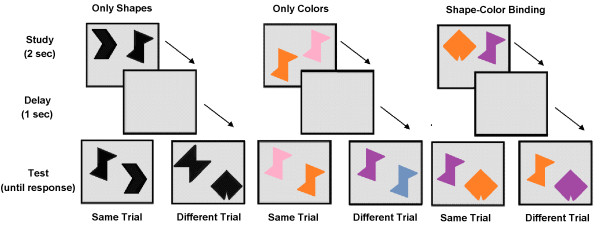

The Short-Term Memory Binding test

The Short-Term Memory Binding (STMB) test is a recognition task that relies on a change detection paradigm. The individual is presented with two consecutive visual arrays of stimuli, which appear simultaneously on the screen and are composed of polygons, colors or combinations of polygon–color targets. The two visual arrays, which are separated by a short delay, are either identical or different, as the stimuli in the second array may change. The individual is asked to decide whether or not there have been changes in the second array. Memory performance of only the polygons and colors are contrasted with performance of the polygon–color combinations. The STMB test assesses feature binding in short-term memory, and recent evidence suggests that this engages the subhippocampal stages of AD [33,34] rather than the hippocampus [35-37] (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Example of Short Term Memory Binding test stimuli.

Contrary to other standard neuropsychological functions, binding deficits on the STMB test do not appear to be a general characteristic of age-related memory changes in healthy aging [38,39] but the test is impaired in sporadic and familial AD as well as asymptomatic carriers of the Presenilin-1 mutation E280A more than 10 years prior to the onset of AD [40-42]. The STMB test is also able to discriminate subjects with preclinical AD from other cohorts [41,42], between healthy aged individuals and those with chronic depression [43], as well as between patients with AD and non-AD dementias [40]. In addition, the STMB test is impervious to differences in age and factors of CR, such as education and cultural background [42]. The STMB task is also not affected by practice or learning effects because the repeated presentation of meaningless stimuli such as polygon–color combinations is quickly overwritten, leaving no memory trace from previous exposures [44,45].

The STMB binding task is being currently used in a multicenter international trial that investigates whether this novel methodology can predict who among those with MCI will go on to develop AD.

Behavioral Pattern Separation-Object task

The Behavioral Pattern Separation-Object (BPS-O) is a visual recognition memory test designed to tax pattern separation [46]. The individual is presented with pictures of common everyday objects interspersed with highly similar lures that vary in levels of mnemonic similarity and the amount of interference with target items. When stimuli were made very different from each other, there was no difference in performance between young and older adults. However, as the stimuli became more similar, performance in older adults was more impaired. This object discrimination task in older adults has shown evidence of robust hippocampal/dentate gyrus/CA3 activation in fMRI studies and sensitivity to early dysfunction in the perforant pathway in aging and amnestic MCI [46-48].

Given the task’s sensitivity to early dysfunction in the perforant pathway, a behavioral version was recently developed [49]. The BPS-O consists of two phases. In the first phase, individuals engage in an indoor/outdoor judgment of common everyday objects. Immediately following this encoding task, individuals are presented with a recognition memory task, in which they must identify each item as old, similar or new. One-third of the items are exact repetitions of items previously presented, one-third of items are new objects never seen before and one-third are perceptually similar but not identical to the target items (that is, lures). The inability to discriminate the lures from the actual target objects indicates a failure in pattern separation (that is, the inability to encode all the details of the object that make it unique; see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Example of Behavioral Pattern Separation-Object task stimuli.

In cognitively normal older adults, pattern separation linearly declined with increasing age [49], while recognition memory did not (that is, subjects correctly recognized whether they saw the object or not). Interestingly, individuals with amnestic MCI had both impaired pattern separation and recognition memory.

In contrast to other traditional tests of memory, the BPS-O allows for the assessment of both recognition memory and pattern separation, making it somewhat unique as a memory measure. The BPS-O also predicts underlying neural function, suggesting that pattern separation performance may serve as a proxy for the integrity of the perforant pathway to the dentate gyrus. Whether the BPS-O may help distinguish normal age-related changes from those in preclinical stages of AD is yet to be determined, but the test does provide an early signal of memory impairments. The BPS-O has been successfully used in a recent MCI intervention trial as an outcome measure [50]. In that trial, pattern separation deficits improved in those MCI subjects exposed to the drug. The BPS-O therefore shows promise for being able to assess change over the brief timeframe of a clinical trial. A computerized version of the BPS-O is also being developed on the iPad with CogState® measures to be used as a secondary outcome measure in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network and the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease prevention trials.

Spatial Pattern Separation task

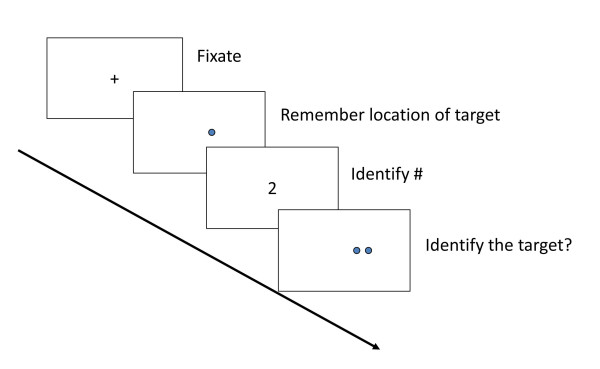

The process of separating similar and overlapping representations into discrete, nonoverlapping representations is a key component of memory formation that is affected in normal aging [46]. A pattern separation task with a spatial component has shown potential sensitivity to preclinical AD [51]. This task requires subjects to discriminate the novel locations of target stimuli. The Spatial Pattern Separation task was adapted from rodent work showing that selective lesions of the dentate gyrus interfere with the ability to discriminate nearby spatial locations [52]. The spatial discrimination element of the pattern separation task may make it more sensitive to early AD pathology because AD-vulnerable regions such as the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex are critically important for spatial memory [53-55].

In each trial of the Spatial Pattern Separation task, subjects view a dot on a computer screen for 3 seconds, followed by a delay of 5 to 30 seconds (during which they read numbers displayed on the screen). Two identical dots then appear, one in the prior location and one in a new location (one of three distances). Individuals must identify the dot at the prior location (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Example of Spatial Pattern Separation task stimuli.

A recent study examined task performance on the Spatial Pattern Separation task in relation to MRI hippocampal volume and CSF measures of amyloid and tau in 37 cognitively normal older individuals [51]. Linear regression analyses (controlling for age and years of education) demonstrated significant relationships between task performance and both bilateral hippocampal volume and CSF Aβ42/pTau181 ratio, a composite measure of amyloid and tau pathology. In contrast to the Spatial Pattern Separation task, a standard paragraph recall test that is sensitive to the MCI stage of AD [56] was not sensitive to these biomarker correlates of preclinical AD. Similar to the BPS-O task, these findings suggest that spatial discrimination in a pattern separation task may also be a sensitive probe for detecting preclinical AD.

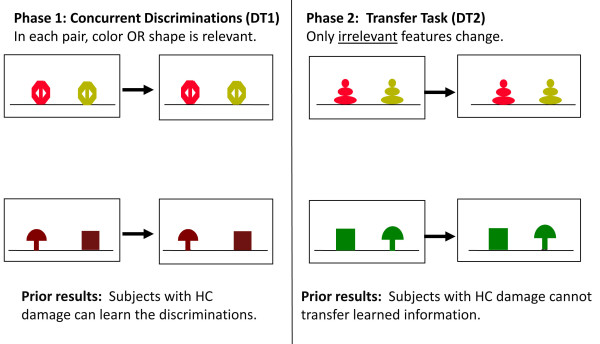

Discrimination and Transfer task

The hippocampus and entorhinal cortex are especially important for generalizing familiar associations in memory [57-59]. Dysfunction in these areas leads to deficits in generalization when familiar information is presented in new ways [52,57,60,61]. In this Discrimination and Transfer task [62,63], subjects learn to discriminate pairs of stimuli determined by shape or color in the discrimination phase and then have to transfer this learned information (the preferred shapes/colors) to novel stimuli in the transfer phase (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Example of Discrimination and Transfer (DT) task in subjects with hippocampal cortex (HC) damage.

Prior work showed that mild–moderate hippocampal atrophy in nondemented older individuals disrupts performance on the transfer phase in this task [62]. At longitudinal follow-up, poor transfer was associated with clinical impairment 2 years after initial testing [63]. These results suggest that this task is sensitive to mild hippocampal atrophy and thus might be a sensitive cognitive marker of pathology associated with preclinical AD. This task was included in the study described above in normal older individuals (n = 37) [51]. In similar linear regression analyses, performance correlated significantly with CSF Aβ42 and the Aβ42/pTau181 ratio, suggesting sensitivity to preclinical AD.

Computerized tests

As AD clinical trials move toward treating presymptomatic individuals, cognitive outcome measures will need to be sensitive for detecting drug effects in cognitively normal subjects. This is problematic if presymptomatic individuals, by definition, are scoring within population-based normative standards. Alternatively, computerized test assessments that provide frequent serial measurements of intra-individual performance over brief time intervals may be uniquely suited for detecting subtle changes in cognitive functioning over the course of a clinical trial. In other words, the measurement of individual variations in performance (that is, either practice effect, the lack of practice or decline) may be more preferable for measuring drug efficacy than determining whether a test score has crossed an arbitrary threshold [64].

A number of computerized cognitive tests have been developed for use in aging populations and clinical trials, which are comprehensively reviewed elsewhere [65,66]. These test batteries often include reaction timed tests, continuous monitoring and working memory tasks, as well as incidental and associative learning. A common advantage of computer batteries is that they provide precision for measuring reaction time and are nonlanguage based so they can be used worldwide. One such commercial battery, CogState®, is being used in the Australian Imaging and Biomarkers Lifestyle study. Decreased performance on specific subtests has been reported in APOE ϵ4-positive individuals and cognitively normal adults with extensive amyloid deposition on amyloid positron emission tomography scans [67-70]. In addition, multiple assessment on a single day was able to successfully differentiate MCI from normal controls by showing a lack of practice effect [71].

Four of the CogState® tests that measure reaction time, working memory and incidental learning are being developed for the iPad along with the FNAME and BPS-O to be used in the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network studies. A composite of these computerized tests along with the hippocampal-based episodic memory measures may provide a sensitive metric for detecting change during the course of these secondary prevention trials.

Other potentially useful measures for the detection of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease

Executive function tasks

While tests of episodic memory have a stronger association with biomarker evidence of preclinical AD, retrospective studies indicate that executive functions may also be declining. In particular, decline on tests of word fluency (that is, F-A-S and category generation), Trailmaking speed and Digit Symbol accelerated 2 to 3 years prior to AD diagnosis [72], as did abstract reasoning over a 22-year surveillance period [73]. However, the association of decline in executive function tasks with biomarker evidence of preclinical AD has been unclear. In a longitudinal analysis, higher Aβ deposition in the frontal and parietal regions was associated with longitudinal decline on Trails B but not at baseline [74]. A recent meta-analysis showed that the association of Aβ deposition with episodic memory had a significantly larger effect size but tests of executive function also showed a significant although weaker association, as measured by a broad range of cognitive tasks [20]. Some believe that this weaker association with executive functions in preclinical AD may suggest that declines in executive functions occur later, relative to memory decline in preclinical AD [73]. On the other hand, an association between white matter hyperintensities and executive function was found, suggesting that a separate neuropathological cascade may occur apart from amyloid accumulation in aging that is associated with cerebrovascular disease [75].

One challenging executive task that does show promise for detecting subtle changes related to preclinical AD is a dual task paradigm. Dual tasking requires an individual to perform two tasks simultaneously (for example, a visuospatial task and a verbal task together) on the premise that cognitive resources are limited and that the interference between the two tasks will cause dual task coordination deficits. A recent study demonstrated that dual tasking impairments occurred in asymptomatic carriers of the E280A Presenilin-1 mutation of familial AD [76], despite normal performances on other neuropsychological and episodic memory tasks. Dual tasking deficits do not normally occur in healthy aging, are impervious to ceiling and practice effects, and show good specificity relative to chronic depression in older individuals [77]. Whether dual task paradigms will be sensitive to older adults with preclinical AD is unknown, but the ability of these tasks to discriminate asymptomatic carriers with familial AD from healthy controls is promising. These findings suggest that we may require more challenging tests of executive function to detect subtle changes at the preclinical AD stage in asymptomatic individuals, similar to episodic memory tasks. More research is needed to determine whether tasks such as the Flanker Inhibitory Control Test and the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task from the National Institutes of Health Toolbox [78] would be sensitive to changes in executive function in the preclinical stages of AD.

Subjective concerns/complaints

Another area of increasing interest is the endorsement of subjective cognitive concerns (SCC) that may prove to be important indicators of an individual’s perception of change during this preclinical stage [79]. Several large longitudinal studies have demonstrated that baseline SCC predict subsequent cognitive decline [80,81] and show promise in detecting AD biomarker positivity at the preclinical stage. For example, cognitively normal individuals who report SCC have reduced hippocampal, parahippocampal, and entorhinal cortex volume on MRI [82], increased Aβ burden [83,84] and reduced glucose metabolism in parietotemporal regions and the parahippocampal gyrus on positron emission tomography imaging, as well as altered fMRI activity in the default mode network [85-87].

There are multiple methods for assessing SCC that range from asking a single question to more formal questionnaires [88-91]. Efforts are underway to systematically identify which SCC may be the most sensitive in the context of preclinical AD. While subjective memory concerns have been investigated most often, there are a few studies that suggest other cognitive domains, such as executive functions, may also be useful [83,92]. Additionally, advanced statistical techniques may help identify specific SCC items that are sensitive at the preclinical stage [93].

Conclusion

This selected review has highlighted some of the promising measures that are being developed to detect the earliest changes associated with biomarker evidence of the preclinical stages of AD in clinically normal older adults. While this is not meant to be an exhaustive survey of potential measures, the review is meant to highlight some promising recent efforts and to emphasize the critical need to develop a new collection of cognitive tasks that are cost-effective, available within the public domain, useful across all levels of CR and derived from translational efforts in cognitive neuroscience. Many of the tests described here will require additional validation, but with the start of secondary prevention trials we now have a unique opportunity to use these trials to determine whether these measures will be useful for detecting preclinical AD and tracking cognitive change over time.

In addition, future efforts are exploring whether more complex activities of daily living (that is, financial competency, navigating complex telephone trees) and other subjective and informant questionnaires related to engagement (that is, physical activities, cognitive stimulation) or emotional states (that is, social isolation, apathy, withdrawal) may be associated with biomarker evidence of preclinical AD. More advanced psychometric techniques, such as Item Response Theory [93-95] and Confirmatory Factor Analysis [75], are now being used to create more sensitive instruments from our current standardized tests as well as composite measures that may capture the individual variance of change in clinically normal individuals [11]. Home assessments and the use of iPad and tablet technologies are also being explored to determine whether more frequent/multiple cognitive assessments may provide a more reliable estimate of change and whether they can be performed without the aid of a technician or extensive travel to a clinic. While many of these efforts are still in development, clinical researchers are attempting to meet the challenge of developing instruments and questionnaires that may be sensitive to biomarker evidence of early AD. Finally, it will probably be a combination of these objective and subjective measures/questionnaires that will be the most valuable for tracking cognitive change over time.

Abbreviations

AD: Alzheimer’s disease; APOE: Apolipoprotein E allele; APOE4: Apolipoprotein E4 carrier status; Aβ: Amyloid beta; BPS-O: Behavioral Pattern Separation-Object; CR: Cognitive reserve; CSF: Cerebral spinal fluid; fMRI: Functional magnetic resonance imaging; FNAME: Face Name Associative Memory Exam; MCI: Mild cognitive impairment; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; SCC: Subjective cognitive concerns; STMB: Short-Term Memory Binding; ϵ4: Carriers of the E4 apolipoprotein E gene.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Dorene M Rentz, Email: drentz@partners.org.

Mario A Parra Rodriguez, Email: mprodri1@staffmail.ed.ac.uk.

Rebecca Amariglio, Email: ramariglio@partners.org.

Yaakov Stern, Email: ys11@columbia.edu.

Reisa Sperling, Email: rsperling@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

Steven Ferris, Email: steven.Ferris@nyumc.org.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all of the subjects who make research possible. MAPR is currently a Fellow of Alzheimer’s Society, UK, Project Grant Number RF165.

References

- Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR Jr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;5:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CC, Ellis KA, Rimajova M, Bourgeat P, Pike KE, Jones G, Fripp J, Tochon-Danguy H, Morandeau L, O’Keefe G, Price R, Raniga P, Robins P, Acosta O, Lenzo N, Szoeke C, Salvado O, Head R, Martins R, Masters CL, Ames D, Villemagne VL. Amyloid imaging results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;5:1275–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KA. Amyloid imaging of Alzheimer’s disease using Pittsburgh Compound B. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;5:496–503. doi: 10.1007/s11910-006-0052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, Dence CS, Lee SY, Mach RH, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Dekosky ST, Morris JC. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;5:446–452. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CC, Ng S, Ackermann U, Gong SJ, Pike K, Savage G, Cowie TF, Dickinson KL, Maruff P, Darby D, Smith C, Woodward M, Merory J, Tochon-Danguy H, O’Keefe G, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Price JC, Masters CL, Villemagne VL. Imaging beta-amyloid burden in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2007;5:1718–1725. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261919.22630.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AM, Mintun MA, Mach RH, Lee SY, Dence CS, Shah AR, Larossa GN, Spinner ML, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, DeKosky ST, Morris JC, Holtzman DM. Inverse relation between in vivo amyloid imaging load and cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 in humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;5:512–519. doi: 10.1002/ana.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Jack CR Jr, Aisen PS. Testing the right target and right drug at the right stage. Sci Transl Med. 2011;5:111–133. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, Price JC, Mathis CA, Tsopelas ND, Ziolko SK, James JA, Snitz BE, Houck PR, Bi W, Cohen AD, Lopresti BJ, DeKosky ST, Halligan EM, Klunk WE. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol. 2008;5:1509–1517. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR Jr, Lowe VJ, Senjem ML, Weigand SD, Kemp BJ, Shiung MM, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Petersen RC. 11C PiB and structural MRI provide complementary information in imaging of Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Brain. 2008;5:665–680. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormino EC, Kluth JT, Madison CM, Rabinovici GD, Baker SL, Miller BL, Koeppe RA, Mathis CA, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ. Episodic memory loss is related to hippocampal-mediated beta-amyloid deposition in elderly subjects. Brain. 2009;5:1310–1323. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storandt M, Mintun MA, Head D, Morris JC. Cognitive decline and brain volume loss as signatures of cerebral amyloid-beta peptide deposition identified with Pittsburgh compound B: cognitive decline associated with Aβ deposition. Arch Neurol. 2009;5:1476–1481. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen NM, Aalto S, Karrasch M, Nagren K, Savisto N, Oikonen V, Viitanen M, Parkkola R, Rinne JO. Cognitive reserve hypothesis: Pittsburgh Compound B and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in relation to education in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;5:112–118. doi: 10.1002/ana.21212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentz DM, Locascio JJ, Becker JA, Moran EK, Eng E, Buckner RL, Sperling RA, Johnson KA. Cognition, reserve, and amyloid deposition in normal aging. Ann Neurol. 2010;5:353–364. doi: 10.1002/ana.21904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe CM, Mintun MA, D’Angelo G, Xiong C, Grant EA, Morris JC. Alzheimer disease and cognitive reserve: variation of education effect with carbon 11-labeled Pittsburgh Compound B uptake. Arch Neurol. 2008;5:1467–1471. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe CM, Mintun MA, Ghoshal N, Williams MM, Grant EA, Marcus DS, Morris JC. Alzheimer disease identification using amyloid imaging and reserve variables: proof of concept. Neurology. 2010;5:42–48. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e620f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Weston A, Graff-Radford NR, Satterfield S, Simonsick EM, Younkin SG, Younkin LH, Kuller L, Ayonayon HN, Ding J, Harris TB. Association of plasma beta-amyloid level and cognitive reserve with subsequent cognitive decline. JAMA. 2011;5:261–266. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012;5:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson BC, Stoub TR, Shah RC, Sperling RA, Killiany RJ, Albert MS, Hyman BT, Blacker D, Detoledo-Morrell L. Alzheimer-signature MRI biomarker predicts AD dementia in cognitively normal adults. Neurology. 2011;5:1395–1402. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182166e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, Head D, Storandt M, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA. Pittsburgh compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;5:1469–1475. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden T, Oh H, Younger AP, Patel TA. Meta-analysis of amyloid–cognition relations in cognitively normal older adults. Neurology. 2013;5:1341–1348. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828ab35d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Delacourte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Meguro K, O’brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;5:734–746. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentz DM, Amariglio RE, Becker JA, Frey M, Olson LE, Frishe K, Carmasin J, Maye JE, Johnson KA, Sperling RA. Face–name associative memory performance is related to amyloid burden in normal elderly. Neuropsychologia. 2011;5:2776–2783. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SL, Celone K, DePeau K, Diamond E, Dickerson BC, Rentz D, Pihlajamaki M, Sperling RA. Age-related memory impairment associated with loss of parietal deactivation but preserved hippocampal activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;5:2181–2186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706818105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Otten LJ, Henson RN. The neural basis of episodic memory: evidence from functional neuroimaging. Philos Trans R Soc London B Biol Sci. 2002;5:1097–1110. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannini P, Hedden T, Becker JA, Sullivan C, Putcha D, Rentz D, Johnson KA, Sperling RA. Age and amyloid-related alterations in default network habituation to stimulus repetition. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;5:1237–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Shannon BJ, LaRossa G, Sachs R, Fotenos AF, Sheline YI, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Morris JC, Mintun MA. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. J Neurosci. 2005;5:7709–7717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2177-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien JL, O’Keefe KM, LaViolette PS, DeLuca AN, Blacker D, Dickerson BC, Sperling RA. Longitudinal fMRI in elderly reveals loss of hippocampal activation with clinical decline. Neurology. 2010;5:1969–1976. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e3966e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celone KA, Calhoun VD, Dickerson BC, Atri A, Chua EF, Miller SL, DePeau K, Rentz DM, Selkoe DJ, Blacker D, Albert MS, Sperling RA. Alterations in memory networks in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: an independent component analysis. J Neurosci. 2006;5:10222–10231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2250-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Chua E, Cocchiarella A, Rand-Giovannetti E, Poldrack R, Schacter DL, Albert M. Putting names to faces: successful encoding of associative memories activates the anterior hippocampal formation. Neuroimage. 2003;5:1400–1410. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00391-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, Laviolette PS, O’Keefe K, O’Brien J, Rentz DM, Pihlajamaki M, Marshall G, Hyman BT, Selkoe DJ, Hedden T, Buckner RL, Becker JA, Johnson KA. Amyloid deposition is associated with impaired default network function in older persons without dementia. Neuron. 2009;5:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amariglio RE, Frishe K, Olson LE, Wadsworth LP, Lorius N, Sperling RA, Rentz DM. Validation of the Face Name Associative Memory Exam in cognitively normal older individuals. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;5:580–587. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2012.666230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamfo R, Armariglio R, Rentz D. Early detection of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease with the Face Name Associative Memory Exam. Senior thesis. Harvard University, Neurobiology; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Didic M, Barbeau EJ, Felician O, Tramoni E, Guedj E, Poncet M, Ceccaldi M. Which memory system is impaired first in Alzheimer’s disease? J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;5:11–22. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staresina BP, Davachi L. Object unitization and associative memory formation are supported by distinct brain regions. J Neurosci. 2010;5:9890–9897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0826-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A, Allen R, Vargha-Khadem F. Is the hippocampus necessary for visual and verbal binding in working memory? Neuropsychologia. 2010;5:1089–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A, Jarrold C, Vargha-Khadem F. Working memory and the hippocampus. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011;5:3855–3861. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekema C, Rijpkema M, Fernandez G, Kessels RP. Dissociating the neural correlates of intra-item and inter-item working-memory binding. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmole JR, Parra MA, Della Sala S, Logie RH. Do binding deficits account for age-related decline in visual working memory? Psychon Bull Rev. 2008;5:543–547. doi: 10.3758/pbr.15.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra MA, Abrahams S, Logie RH, Sala SD. Age and binding within-dimension features in visual short-term memory. Neurosci Lett. 2009;5:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.10.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Sala S, Parra MA, Fabi K, Luzzi S, Abrahams S. Short-term memory binding is impaired in AD but not in non-AD dementias. Neuropsychologia. 2012;5:833–840. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra MA, Abrahams S, Logie RH, Mendez LG, Lopera F, Della Sala S. Visual short-term memory binding deficits in familial Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2010;5:2702–2713. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra MA, Sala SD, Abrahams S, Logie RH, Mendez LG, Lopera F. Specific deficit of colour-colour short-term memory binding in sporadic and familial Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2011;5:1943–1952. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra MA, Abrahams S, Logie RH, Della Sala S. Visual short-term memory binding in Alzheimer’s disease and depression. J Neurol. 2010;5:1160–1169. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5484-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colzato LS, Raffone A, Hommel B. What do we learn from binding features? Evidence for multilevel feature integration. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2006;5:705–716. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.32.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie RH, Brockmole JR, Vandenbroucke ARE. Bound feature combinations in visual short term memory are fragile but influence long-term learning. Vis Cogn. 2009;5:160–179. [Google Scholar]

- Stark SM, Yassa MA, Stark CE. Individual differences in spatial pattern separation performance associated with healthy aging in humans. Learn Mem. 2010;5:284–288. doi: 10.1101/lm.1768110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassa MA, Mattfeld AT, Stark SM, Stark CE. Age-related memory deficits linked to circuit-specific disruptions in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;5:8873–8878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101567108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassa MA, Stark SM, Bakker A, Albert MS, Gallagher M, Stark CE. High-resolution structural and functional MRI of hippocampal CA3 and dentate gyrus in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2010;5:1242–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark SM, Yassa MA, Lacy JW, Stark CE. A task to assess behavioral pattern separation (BPS) in humans: data from healthy aging and mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia. 2013. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bakker A, Krauss GL, Albert MS, Speck CL, Jones LR, Stark CE, Yassa MA, Bassett SS, Shelton AL, Gallagher M. Reduction of hippocampal hyperactivity improves cognition in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuron. 2012;5:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau H, Karantzoulis S, Myers C, Pirraglia E, Li Y, Gurnani A, Glodzik L, Scharfman H, Kesner RP, de Leon M, Ferris S. Cognitive detection of preclinical AD. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;5:P358. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP. Role of the rodent hippocampus in paired-associate learning involving associations between a stimulus and a spatial location. Behav Neurosci. 2002;5:63–71. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun VH, Leutgeb S, Wu HQ, Schwarcz R, Witter MP, Moser EI, Moser MB. Impaired spatial representation in CA1 after lesion of direct input from entorhinal cortex. Neuron. 2008;5:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadel L, MacDonald L. Hippocampus: cognitive map or working memory? Behav Neural Biol. 1980;5:405–409. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(80)90430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald CJ, Good M. The effects of combined lesions of the subicular complex and the entorhinal cortex on two forms of spatial navigation in the water maze. Behav Neurosci. 2000;5:211–217. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.114.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger A, Ferris SH, Golomb J, Mittelman MS, Reisberg B. Neuropsychological prediction of decline to dementia in nondemented elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1999;5:168–179. doi: 10.1177/089198879901200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H, Mathews P, Cohen NJ. Further studies of hippocampal representation during odor discrimination learning. Behav Neurosci. 1989;5:1207–1216. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.103.6.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluck MA, Myers CE, Nicolle MM, Johnson S. Computational models of the hippocampal region: implications for prediction of risk for Alzheimer’s disease in non-demented elderly. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;5:247–257. doi: 10.2174/156720506777632826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winocur G, Olds J. Effects of context manipulation on memory and reversal learning in rats with hippocampal lesions. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1978;5:312–321. doi: 10.1037/h0077468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckmaster CA, Eichenbaum H, Amaral DG, Suzuki WA, Rapp PR. Entorhinal cortex lesions disrupt the relational organization of memory in monkeys. J Neurosci. 2004;5:9811–9825. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1532-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cermak LS, Uhly B, Reale L. Encoding specificity in the alcoholic Korsakoff patient. Brain Lang. 1980;5:119–127. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(80)90115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers CE, Kluger A, Golomb J, Ferris S, de Leon MJ, Schnirman G, Gluck MA. Hippocampal atrophy disrupts transfer generalization in nondemented elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2002;5:82–90. doi: 10.1177/089198870201500206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers CE, Kluger A, Golomb J, Gluck MA, Ferris S. Learning and generalization tasks predict short-term cognitive outcome in nondemented elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008;5:93–103. doi: 10.1177/0891988708316858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby D, Brodtmann A, Woodward M, Budge M, Maruff P. Using cognitive decline in novel trial designs for primary prevention and early disease-modifying therapy trials of Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;5:1376–1385. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211000354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PJ, Jackson CE, Petersen RC, Khachaturian AS, Kaye J, Albert MS, Weintraub S. Assessment of cognition in mild cognitive impairment: a comparative study. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;5:338–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild K, Howieson D, Webbe F, Seelye A, Kaye J. Status of computerized cognitive testing in aging: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;5:428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonnington CM, Locke DE, Dueck AC, Caselli RJ. Anxiety affects cognition differently in healthy apolipoprotein E ϵ4 homozygotes and non-carriers. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;5:294–299. doi: 10.1176/jnp.23.3.jnp294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby DG, Brodtmann A, Pietrzak RH, Fredrickson J, Woodward M, Villemagne VL, Fredrickson A, Maruff P, Rowe C. Episodic memory decline predicts cortical amyloid status in community-dwelling older adults. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;5:627–637. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YY, Pietrzak RH, Ellis KA, Jaeger J, Harrington K, Ashwood T, Szoeke C, Martins RN, Bush AI, Masters CL, Rowe CC, Villemagne VL, Ames D, Darby D, Maruff P. Rapid decline in episodic memory in healthy older adults with high amyloid-beta. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;5:675–679. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YY, Ellis KA, Pietrzak RH, Ames D, Darby D, Harrington K, Martins RN, Masters CL, Rowe C, Savage G, Szoeke C, Villemagne VL, Maruff P. AIBL Research Group. Stronger effect of amyloid load than APOE genotype on cognitive decline in healthy older adults. Neurology. 2012;5:1645–1652. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e9ae6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby D, Maruff P, Collie A, McStephen M. Mild cognitive impairment can be detected by multiple assessments in a single day. Neurology. 2002;5:1042–1046. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.7.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias MF, Beiser A, Wolf PA, Au R, White RF, D’Agostino RB. The preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease: a 22 year prospective study of the Framingham cohort. Arch Neurol. 2000;5:808–813. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.6.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Hall CB, Lipton RB, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM, Kawas C. Memory impairment, executive dysfunction, and intellectual decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;5:266–278. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SM, Sojkova J, Zhou Y, An Y, Ye W, Holt DP, Dannals RF, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Ferrucci L, Kraut MA, Wong DF. Longitudinal cognitive decline is associated with fibrillar amyloid-beta measured by [11C]PiB. Neurology. 2010;5:807–815. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d3e3e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden T, Mormino EC, Amariglio RE, Younger AP, Schultz AP, Becker JA, Buckner RL, Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Rentz DM. Cognitive profile of amyloid burden and white matter hyperintensities in cognitively normal older adults. J Neurosci. 2012;5:16233–16242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2462-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson SE, Parra MA, Moreno S, Lopera F, Della Sala S. Dual task abilities as a possible preclinical marker of Alzheimer’s disease in carriers of the E280A presenilin-1 mutation. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;5:234–241. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711001561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschel R, Logie RH, Kazen M, Della Sala S. Alzheimer’s disease, but not ageing or depression, affects dual-tasking. J Neurol. 2009;5:1860–1868. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Tulsky DS, Zelazo PD, Bauer PJ, Carlozzi NE, Slotkin J, Blitz D, Wallner-Allen K, Fox NA, Beaumont JL, Mungas D, Nowinski CJ, Richler J, Deocampo JA, Anderson JE, Manly JJ, Borosh B, Havlik R, Conway K, Edwards E, Freund L, King JW, Moy C, Witt E, Gershon RC. Cognition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology. 2013;5:S54–S64. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872ded. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Prichep L, Mosconi L, John ER, Glodzik-Sobanska L, Boksay I, Monteiro I, Torossian C, Vedvyas A, Ashraf N, Jamil IA, de Leon MJ. The pre-mild cognitive impairment, subjective cognitive impairment stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;5:S98–S108. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dik MG, Jonker C, Comijs HC, Bouter LM, Twisk JW, van Kamp GJ, Deeg DJ. Memory complaints and APOE-ϵ4 accelerate cognitive decline in cognitively normal elderly. Neurology. 2001;5:2217–2222. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.12.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield PW, Marder K, Dooneief G, Jacobs DM, Sano M, Stern Y. Association of subjective memory complaints with subsequent cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly individuals with baseline cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;5:609–615. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ, Wishart HA, Rabin LA, Santulli RB, Flashman LA, West JD, McHugh TL, Mamourian AC. Older adults with cognitive complaints show brain atrophy similar to that of amnestic MCI. Neurology. 2006;5:834–842. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234032.77541.a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amariglio RE, Becker JA, Carmasin J, Wadsworth LP, Lorius N, Sullivan C, Maye JE, Gidicsin C, Pepin LC, Sperling RA, Johnson KA, Rentz DM. Subjective cognitive complaints and amyloid burden in cognitively normal older individuals. Neuropsychologia. 2012;5:2880–2886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotin A, Mormino EC, Madison CM, Hayenga AO, Jagust WJ. Subjective cognition and amyloid deposition imaging: a Pittsburgh Compound B positron emission tomography study in normal elderly individuals. Arch Neurol. 2012;5:223–229. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafkemeijer A, Altmann-Schneider I, Oleksik AM, van de Wiel L, Middelkoop HA, van Buchem MA, van der Grond J, Rombouts SA. Increased functional connectivity and brain atrophy in elderly with subjective memory complaints. Brain Connect. 2013;5:353–362. doi: 10.1089/brain.2013.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosconi L, De Santi S, Brys M, Tsui WH, Pirraglia E, Glodzik-Sobanska L, Rich KE, Switalski R, Mehta PD, Pratico D, Zinkowski R, Blennow K, de Leon MJ. Hypometabolism and altered cerebrospinal fluid markers in normal apolipoprotein E E4 carriers with subjective memory complaints. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;5:609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Risacher SL, West JD, McDonald BC, Magee TR, Farlow MR, Gao S, O’Neill DP, Saykin AJ. Altered default mode network connectivity in older adults with cognitive complaints and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;5:751–760. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amariglio RE, Townsend MK, Grodstein F, Sperling RA, Rentz DM. Specific subjective memory complaints in older persons may indicate poor cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;5:1612–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Cahn-Weiner D, Jagust W, Baynes K, Decarli C. The measurement of everyday cognition (ECog): scale development and psychometric properties. Neuropsychology. 2008;5:531–544. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.4.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilewski MJ, Zelinski EM, Schaie KW. The Memory Functioning Questionnaire for assessment of memory complaints in adulthood and old age. Psychol Aging. 1990;5:482–490. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, v SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;5:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Norden AG, Fick WF, de Laat KF, van Uden IW, van Oudheusden LJ, Tendolkar I, Zwiers MP, de Leeuw FE. Subjective cognitive failures and hippocampal volume in elderly with white matter lesions. Neurology. 2008;5:1152–1159. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327564.44819.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snitz BE, Yu L, Crane PK, Chang CC, Hughes TF, Ganguli M. Subjective cognitive complaints of older adults at the population level: an item response theory analysis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;5:344–351. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182420bdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, Narasimhalu K, Gibbons LE, Mungas DM, Haneuse S, Larson EB, Kuller L, Hall K, van Belle G. Item response theory facilitated cocalibrating cognitive tests and reduced bias in estimated rates of decline. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;5:1018–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane PK, Narasimhalu K, Gibbons LE, Pedraza O, Mehta KM, Tang Y, Manly JJ, Reed BR, Mungas DM. Composite scores for executive function items: demographic heterogeneity and relationships with quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;5:746–759. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708081162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]