Abstract

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore the meaning and use of spirituality among African American (AA), predominantly Christian women with HIV. A nonrandom sample of 20 AA women from a large infectious disease clinic in Metro-Atlanta participated in the study. The study used focus groups and individual interviews to interview women about their lived spiritual experience. Content analysis and NUDIST software were used to analyze transcripts. The findings revealed the spiritual views and practices of AA women with HIV. The following themes (and subthemes) emerged: Spirituality is a process/journey or connection (connection to God, higher power, or spirit and HIV brought me closer to God), spiritual expression (religion/church attendance, prayer, helping others, having faith), and spiritual benefits (health/healing, spiritual support, inner peace/strength/ability to keep going, and here for a reason or purpose/a second chance). Findings highlight the importance of spirituality in health and well-being among AA women with HIV/AIDS.

Keywords: focus groups, methods, qualitative methods, immune clinical focus, spirituality, health behavior/symptom focus, Black population focus, HIV/AIDS

Spirituality and religion have historically served important roles within African American (AA) culture and communities, including coping, survival, maintaining overall well-being, and improving health outcomes (Chester, Himburg, & Weatherspoon, 2006; Figueroa, Davis, Baker, & Bunch, 2006; Giger, Appel, Davidhizar, & Davis, 2008; Holt & McClure, 2006; Mattis, 2002; Newlin, Knafl, & Melkus, 2002), and are also particularly important among many AA women, in general (Mattis, 2000, 2002), and AA HIV-positive women (Braxton, Lang, Sales, Wingood, & DiClemente, 2007; Coleman & Holzemer, 1999; Polzer Casarez & Miles, 2008). Spirituality may involve feelings of connection to others and finding meaning in life (Barnum, 1996; Freidmann, Mouch, & Racey, 2002; O'Brien, 2003; Simoni, Martone, & Kerwin, 2002); however, each person and patient may define or experience spirituality in various and unique ways. Therefore, to provide holistic care, it is important for health care providers to identify and consider patients’ individual spirituality and spiritual needs, meaning, and relevance to health. The purpose of this article is to describe the meaning and use of spirituality of AA women living with HIV/AIDS in the Southeastern United States. The knowledge gained can assist in the development and evaluation of improved measures and interventions to enhance well-being and quality of life for this vulnerable population.

Defining Spirituality

The literature includes many definitions of spirituality, some of which have been derived by studying various cultural groups and patient populations. This summary highlights several broad definitions and goes beyond definitions specific to AAs or AA HIV-positive women. As a concept, spirituality is multifaceted with attributes that include belief in a higher power, transcendence, meaning and purpose of life, resource, connectedness, and interconnectedness (Abeles et al., 1999; Coward & Reed, 1996; Freidmann et al., 2002; Haase, Britt, Coward, Leidy, & Penn, 1992; Mattis, 2000; Post, Puchalski, & Larson, 2000; Simoni et al., 2002). Connectedness can pertain to a connection with oneself, with a higher power, and with others (Abeles et al., 1999; Friedmann et al., 2002; Mattis, 2000; Nolan & Crawford, 1997; Simoni et al., 2002). In addition to a belief in God or a higher power, spirituality may also be understood in terms of a person's beliefs regarding the nonmaterial forces of life and nature (O'Brien, 2003). Overall, spirituality can be described as an individual's search for meaning and purpose in life that may be guided by a set of beliefs in a higher power and involve a personal connection with that higher power, others or self, and often has a focus beyond self (self-transcendence), the physical world, and visible realities (transcendence).

Spirituality and Religion

Religion and spirituality are often used interchangeably (Koenig, George, Titus, & Meador, 2004; Mattis, 2000) and may sometimes overlap (Mattis, 2000, 2002); however, there are some differences that are noted by lay people (Mattis, 2000) and in the literature. Spirituality is a broader concept than religion (Emblen, 1992; Goldberg, 1998; McSherry & Draper, 1998; Mueller, Plevak, & Rummans, 2001; Seeman, Dubin, & Seeman, 2003) and may or may not be related to organized religion (Miller & Thoresen, 2003). The type of belief inherent to spirituality is broader than that of religiosity, which often refers to an individual's beliefs and behaviors associated with a specific religious tradition (O'Brien, 2003). According to some, that which is spiritual transcends personal and scientific boundaries (Reed, 1992) and also physical boundaries, whereas religion is defined by boundaries of religious doctrine (Miller & Thoresen, 2003). Relative to HIV, Woods and Ironson (1999) found that persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) were more likely to identify themselves as spiritual rather than religious and appeared to use spirituality more than religion in coping with their disease. PLWHA may embrace spirituality more than religion due to perceptions or experiences of HIV-related stigmatization by mainstream religious traditions (Koenig & Cohen, 2002).

Spirituality and Religion

Among AA Women

Spirituality has various meanings—both shared and distinct—even among people with similar cultures and backgrounds. For example, among AA women, spirituality has been assigned a variety of meanings, definitions, descriptions, and interpretations. Among AA women, definitions of spirituality vary across individuals, women also hold multiple definitions of spirituality, and they make distinctions between spirituality and religiosity (Mattis, 2000). Of the 13 categorical definitions of spirituality that emerged from a qualitative study of 128 AA women, the most prevalent were as follows: (a) connection to or belief in a higher external power (53%); (b) consciousness of metaphysicality (24%); (c) understanding, accepting, being in touch with self (23%); and (d) life direction, life instructions, guidance (22%). In a subsample (n = 21) of these AA women, three differences between religiosity and spirituality were identified: (a) Religiosity is associated with organized worship, whereas spirituality is the internalization of positive values; (b) religion is conceptualized as a path and spirituality as an outcome; and (c) religion is tied to worship and spirituality is associated with relationships. However, spirituality and religion—both—play key roles in helping AA women to cope and make meaning in times of adversity, by accepting reality, engaging in spiritual surrender, confronting/transcending limitations, dealing with existential issues, recognizing purpose/destiny, defining character and acting meaningful/moral, achieving growth, and trusting in the transcendent (Mattis, 2002). Spirituality and religion may affect the physical and psychological well-being of AAs and AA women.

Spirituality and Meaning or Purpose in Life

A growing number of researchers recognize the importance of including spirituality in health research; however, few studies have explored spirituality and meaning in life among AA women living with HIV/AIDS in the Southeastern United States. Studies have identified the importance and/or benefits of spirituality and meaning or purpose in life in PLWHA (Bosworth, 2006; Carson & Green, 1992; Coward, 1995; Dalmida, 2006; Dalmida, Holstad, DiIorio, & Laderman, 2009; Dalmida, Holstad, DiIorio, & Laderman, 2010; Dunbar, Mueller, Medina, & Wolf, 1998; Fryback & Reinert, 1999; Guillory, Sowell, Moneyham, & Seales, 1997; Hall, 1998; Litwinczuk & Groh, 2007; Lorenz et al., 2005; O'Connell & Skevington, 2005; Polzer Casarez & Miles, 2008; Ridge, Williams, Anderson, & Elford, 2008; Scarinci, Griffin, Grogoriu, & Fitzpatrick, 2009; Somlai, Heckman, Hackl, Morgan, & Welsh, 1998; Tarakeshwar, Khan & Sikkema, 2006; Tuck & Thinganjana, 2007). Only a portion of these studies was conducted among women living with HIV/AIDS to explore the meaning or role of spirituality in their lives (Coward, 1995; Dalmida, 2006; Dalmida et al. 2009; Dalmida et al., 2010; Dunbar et al., 1998; Guillory et al., 1997; Polzer Casarez & Miles, 2008; Scarinci et al., 2009; Somlai et al., 1998), and only one was with AA HIV-positive women (Polzer Casarez & Miles, 2008).

Spirituality and People Living With HIV/AIDS

Several qualitative studies have focused on the examination of different aspects of spirituality among PLWHA. One study, based on the work of Viktor Frankl (Carson & Green, 1992) among 100 persons with HIV, found that people with higher spiritual well-being (SWB) and who found meaning and purpose in their lives were also psychologically hardier. Among persons with advanced HIV disease, Hall (1998) found that for most participants, organized religion acted as a barrier to attaining spirituality until their anger was ameliorated. For some women, HIV provided them with a purpose for their life and having this purpose also gave them confidence in their spirituality (Hall, 1998). Common themes identified were as follows: Purpose in life emerges from stigmatization, opportunities for meaning arise from a disease without a cure, and after suffering, spirituality frames the life (Hall, 1998). Tarakeshwar et al. (2006) conducted individual interviews with 20 PLWH to examine how religion/spirituality influenced their coping process. Findings suggested that the HIV diagnosis facilitated the development of a relationship-based framework that included relationships with God, life, and family. More recently, Tuck and Thinganjana (2007) explored the meaning of spirituality among PLWHA and healthy adults. Among female PLWHA, spirituality was described as a belief in God, a help or source, and as one's essence or center, and many discussed spirituality existentially, referring to a search for a reason or purpose for living. Similarly, the importance of spirituality was identified among Black African men and women with HIV in the United Kingdom and also subjective reports of the benefits received from prayer and helping others (Ridge et al., 2008). Among African people with HIV in Nambia, participants reported that religious beliefs made their HIV status more meaningful and provided a purpose to their HIV infection (Plattner & Meiring, 2006).

Spirituality and HIV-Positive Women

Many HIV-positive women consider spirituality to be an important resource to help cope with the stressors and demands associated with living with HIV disease (Arnold, Avants, Margolin & Marcotte, 2002; Bosworth, 2006; McCormick, Holder, Wetsel, & Cawthon, 2001; Powell, Shahabi, & Thoresen, 2003; Sowell et al., 2001). Guillory et al. (1997) conducted focus groups (FGs) among women with HIV to explore the use of and meaning attributed to spirituality and found that participants reported a strong reliance on God and viewed spirituality as essential to daily life and healing. Using a phenomenological approach, Coward (1995) found that women with AIDS find meaning and purpose in their life through their experiences of giving to and receiving from others and by maintaining hope, and that the ability to find meaning in life assisted many women inhealing and growth. Interviews with 34 women with HIV yielded five components that were important to their psychological and spiritual growth: reckoning with death, life affirmation, creation of meaning, self-affirmation, and redefining relationships (Dunbar et al., 1998). Overall, spirituality has been associated with a variety of positive health outcomes for HIV-positive women, including an improvement in depressive symptoms (Braxton et al., 2007; Dalmida et al., 2009), immune function (Dalmida et al., 2009), quality of life (QOL; Grimsley 2006; Sowell et al. 2001) and longer HIV-related survival (Ironson et al. 2002; Ironson et al. 2006), but only few of these studies have been conducted among HIV-positive AA women.

Spirituality Among HIV-Positive Black/AA Women

Spirituality and religion are important to many AAs living with HIV disease (Braxton et al., 2007; Coleman & Holzemer, 1999; Dalmida et al., 2009; Dalmida et al., 2010; Polzer Casarez & Miles, 2008) and, particularly among AA women with HIV, serve as a cultural strength (Polzer Casarez & Miles, 2008) and psychological resource (Braxton et al., 2007). Polzer Casarez and Miles conducted content analysis of interviews to explore how spirituality affected the lives of 38 AA mothers living with HIV and found that, through a relationship with God, women were able to reduce their stress and worry about their own health and that of their infants. Using quantitative methods, Braxton et al. (2007) found that spirituality was significantly associated with reduced depressive symptoms among a sample of 308 HIV-positive Black women in a large HIV behavioral trial. Similarly, Dalmida et al. (2009) found significant inverse associations between depressive symptoms and spiritual wellbeing (r = –.55, p = .0001), and its components, existential well-being (r = –.62, p = .0001) and religious well-being (r = –.36, p = .0001) among a sample of 129 HIV-positive, predominantly AA women. These researchers also found significant positive associations between spirituality and immune function and health-related quality of life among HIV-positive AA women (Dalmida et al., 2009; Dalmida et al., 2010). Still, not enough is known about the spiritual and religious perceptions and experiences of women living with HIV/AIDS and their use and role in living with the disease. The purpose of this article is to describe the meaning and use of spirituality among a sample of AA women living with HIV. The main research questions were as follows:

Research Question 1: What is the meaning of spirituality to women living with HIV?

Research Question 2: How do women with HIV describe their experience with spirituality (spiritual experience)?

These questions were addressed using FG discussions and individual interviews. Excerpts of oral narratives were used to highlight the findings of this study.

Method

This article reports on findings from a primarily qualitative study conducted with 20 AA women living with HIV disease to obtain a range of descriptions of women's perceptions and use of spirituality. The meaning and use of spirituality in the context of HIV infection was explored in two group sessions using FG methodology and six individual interviews using a FG guide, a semistructured interview script, and a phenomenological approach to better comprehend HIV-positive women's lived spiritual experiences and perceptions. Women also completed a sociodemographic questionnaire and the 20-item Spiritual Well-Being Scale (described below). The University Institutional Review Board approved the study, and all women gave written informed consent.

Participants

Purposive sampling was used to recruit women from a large infectious disease center in the Southeastern United States to participate in FGs and individual interviews about spirituality. To be eligible to participate, women had to be (a) infected with HIV; (b) female by birth; (c) able to read, write, and speak English; (d) 18 years or older; and (e) willing to participate in a FG (and potentially also an individual interview) and complete two questionnaires. The sample consisted of 20 HIV-positive AA women; however, being AA or Black was not an inclusion criterion. Women participated in one FG, and six of the women participated in individual interviews.

Data Collection

Qualitative and quantitative measures were used to collect data about participants’ spirituality and to describe the sample: (a) demographic and SWB questionnaire, (b) FG session, and (c) individual interviews.

Sociodemographic questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire consisted of 24 items that elicited information about, age, race, ethnicity, income, occupation, marital status, number of children, religious affiliation, and religious or spiritual beliefs and practices.

SWB

It was assessed using the SWB scale (Ellison, 1983; Ellison & Paloutzian, 1982), which has 20 items and comprises two subscales: Religious Well-Being (RWB) and Existential Well-Being (EWB). The 10 odd-numbered items represent the RWB subscale and measure the degree to which a person perceives her SWB to be expressed in relation to God. The 10 even-numbered items represent the EWB subscale and assesses SWB relative to meaning and purpose in their life. The total SWB score ranges from 20 to 120, representing lower and higher SWB, respectively. Scores on the EWB and RWB subscales range from 10 to 60 each, representing low to high EWB or RWB, respectively. Based on original testing, test–retest reliability of the SWB scale is more than .85.

FG interviews

Two FGs were conducted using procedures consistent with the recommendations of Krueger and Casey's (2000) FG guide. A semistructured interview guide consisting of open-ended questions about spiritual beliefs, experience, and practices was used to conduct the FGs. The researcher facilitated each FG session with the help of an AA female cofacilitator. The sessions were conducted in a private room at the infectious disease clinic and each lasted approximately 90 min. Each FG was audiotaped and consisted of open-ended questions such as “How do women living with HIV describe their experience with spirituality?” Participants were asked to share their view and understanding of the meaning of spirituality. In addition, they were asked to discuss what role their spiritual beliefs or practices play, if any, in their health status, decisions, and practices. At the end of the FG sessions, women who were interested in participating in individual interviews provided their contact information. Participants were reimbursed US$10 for their time.

Individual interviews

After both FGs were conducted, six women (three from each FG) were invited to participate in individual interviews to further discuss their spiritual beliefs and practices and the role that spirituality plays in their health and in their overall lives with HIV. Women were invited based on level of participation, length of time with HIV/AIDS, and variation in experiences shared during the FG and background (i.e., several more expressive, one more quiet during FG, who reported no belief in God and living with HIV < 10 years, two Catholics, two Baptists, one Christian, all with varying length of time with HIV, etc.). The interviews were conducted by the researcher and were also audiotaped. These participants were reimbursed an additional US$10 for their time. The interviews were conducted in a private room at the infectious disease clinic and lasted between 30 and 90 min. An example of an open-ended interview question asked is “Tell me about an experience that felt spiritual to you.” Questions for the individual interviews were generated from the FG questions and were modified based on the FG discussions. The individual interview questions were similar to the FG questions, but allowed for a more detailed personal account of the women's lived spiritual experience in the context of being HIV-positive.

Analysis

Each FG interview was transcribed verbatim and the transcript was analyzed as one (grouped) text. Narrative data from FG sessions and individual interviews were analyzed separately using interpretive phenomenology (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000), content analysis, and NUDIST software for qualitative analysis, and then comparisons were made across FGs and interviews. Once an understanding of overall text was obtained by reading transcripts and data several times, phrases in text were highlighted and theme names were assigned to the text, as they emerged from the narratives. Line-by-line coding and thematic analysis was done, and all important phrases were labeled with tentative theme names (Cohen, Kahn, & Steeves, 2000). A coding scheme (Rubin & Rubin, 2005) was developed, using a precise definition for each theme, and was used to code concepts and themes and identify the overall relationship between the codes. In the attempt to reduce bias, the researcher engaged in the phenomenological reduction process of bracketing, used peer review and content experts, and did member checking (Cohen et al., 2000; Reed, 1992). The coding scheme and a segment of the de-identified transcripts were given to two colleagues and a qualitative research expert for review and critique. Based on their suggestions, the initial coding scheme was modified by merging some of the categories that were similar and by combining some of the free nodes (coding categories) created using the NUDIST software with some of the relevant tree nodes. All of the transcripts were recoded with the revised coding scheme, which yielded nonoverlapping themes. To check credibility of the data and to confirm study findings, member checking was done by asking 15 of the participants to review a list of themes that were identified and all agreed that the themes were consistent with what was discussed.

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages from the demographic data and mean SWB scale score, were calculated using SPSS 15.0 statistical software package.

Results

The characteristics for the study sample are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the sample was 46.8 ± 6.5 years and mean number of years since their HIV diagnosis was 13 ± 5.26 years. Majority of the women were single, unemployed, or on disability, and were economically impoverished.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Mean Spiritual Well-Being Scores

| Variable and Demographic | N | % | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual well-being | 101.7 | 12.61 | 66-120 | ||

| Religious well-being | 53.4 | 7.57 | 28-60 | ||

| Existential well-being | 8.4 | 6.62 | 35-60 | ||

| Age | 46.84 | 6.46 | 38-61 | ||

| Years since HIV diagnosis | 13 | 5.26 | 3-24 | ||

| Number of children | 1.72 | 1.64 | 0-5 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Black | 20 | 100 | |||

| Educational level | |||||

| 9th-12th grade | 9 | 45 | |||

| High school or GED | 3 | 15 | |||

| College or technical school | 8 | 40 | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 1 | 5 | |||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 8 | 40 | |||

| Single | 11 | 55 | |||

| Employment status | |||||

| Part-time | 2 | 10 | |||

| Unemployed or on disability | 18 | 90 | |||

| Annual income | |||||

| US$0-US$10,999 | 16 | 80 | |||

| US$11,000-US$20,99 | 3 | 15 | |||

| US$21,000-US$30,999 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Religious service attendance | |||||

| Never | 1 | 5 | |||

| One to three times a month | 9 | 45 | |||

| More than once a week | 7 | 35 | |||

| Daily | 3 | 15 | |||

| Prayer | |||||

| Never | 2 | 10 | |||

| Once a week or more | 2 | 10 | |||

| Daily or nearly every day | 16 | 80 | |||

| Meditation | |||||

| Never | 7 | 35 | |||

| One to three times a month | 5 | 25 | |||

| Once a week | 3 | 15 | |||

| Daily or nearly every day | 5 | 25 | |||

| Reading spiritual materials | |||||

| Never | 2 | 10 | |||

| One to three times a month | 5 | 25 | |||

| Once a week or more | 4 | 20 | |||

| Daily or nearly every day | 9 | 45 | |||

| Importance of spiritual beliefs | |||||

| Moderately important | 1 | 5 | |||

| Very or extremely important | 19 | 95 | |||

| Religious affiliation | |||||

| No belief in God | 1 | 5 | |||

| Belief in God, no affiliation | 1 | 5 | |||

| Christian | 10 | 50 | |||

| Baptist | 3 | 15 | |||

| Catholic | 1 | 5 | |||

| Not reported | 4 | 20 |

Note: GED = general education development.

On average, the sample had high SWB scores and majority (95%) of the women considered spirituality as “very” or “extremely” important. This is a reflection of the high self-reported spiritual wellness and importance of spirituality among the women in the study, who all self-identified as spiritual, except one, who still rated spirituality as important. The sample was predominantly Christian, including (nonspecific) Christian (n = 10), Baptist (n = 3), and Catholic (n = 1). The sample's religious/spiritual practices varied and only few (10%) reported never praying or reading religious/ spiritual material. Half of the sample (n = 10) attended religious services more than once per week.

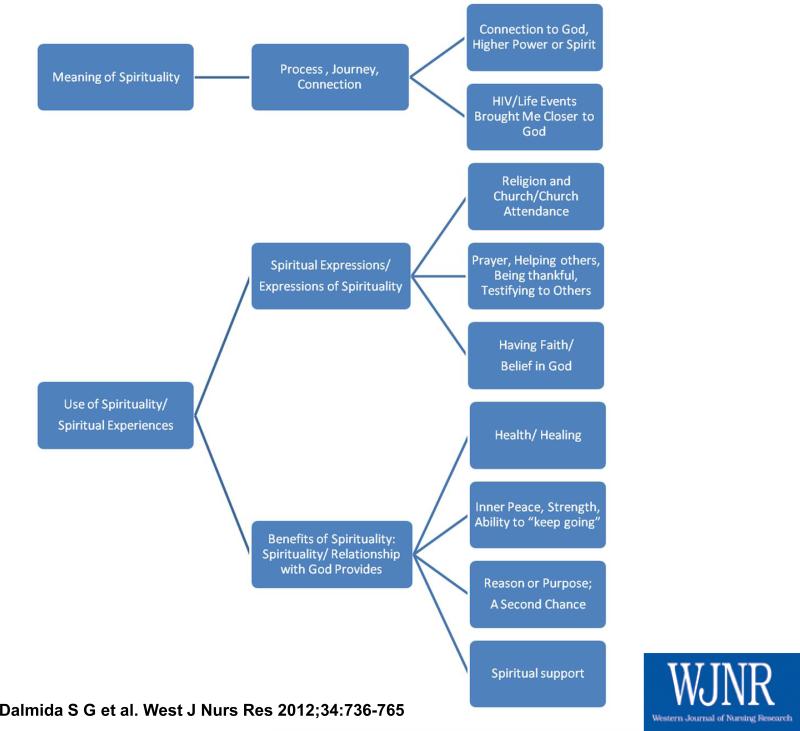

An analysis of the data across cases resulted in three main themes and nine subthemes (Figure 1); all three of the main themes were discussed across, the FGs and the individual interviews, and one additional major subtheme emerged from the individual interviews only (Table 2). The themes offer a description of the spiritual experiences of predominantly Christian AA women living with HIV. Participants’ quotes are presented for FGs, and pseudonyms are used for quotes from women in the individual interviews.

Figure 1.

Diagram of categories, themes, and subthemes of spirituality of AA women with HIV

Table 2.

Themes of Spirituality Among African American Women Living With HIV

| Major Categories/Themes | Subcategories/Themes |

|---|---|

| Spirituality is a process or journey/connection | Connection to God or higher power |

| HIV/life events brought closer to God | |

| Expressions of spirituality | Religion and church/church attendance |

| Prayer, helping others, being thankful | |

| Testifying to others | |

| Having faith/belief in Godc | |

| Spirituality/relationship with God provides | Health/healinga |

| Inner peace, strength, ability to “keep going”b | |

| Spiritual support | |

| Reason or purpose; a second chancec |

Main theme in individual interviews and subtheme in focus groups.

Focus groups only.

Interviews only.

The emergent themes are organized into two categories: (a) the meaning of spirituality and (b) use of spirituality and spiritual experiences (Figure 1). The first category contains one main theme and two subthemes, and the second category contains two main themes and nine subthemes. These categories, themes and subthemes, are described in more detail in the following.

Meaning of Spirituality

Theme 1: Spirituality is a process, journey, and connection to God/higher power/spirit

Spirituality was described as a process that occurred over a period of time or as a journey in which they had varying experiences of spirituality and spiritual growth. For example, one FG respondent said,

It's a process. And I thank God that we can meditate and pray and all of these things, to help us . . . get to where he wants us to be and be the person he wants us to be.

Other women in the FGs talked about the process of spirituality in terms of having different levels, stages, or different degrees of closeness to one's higher power. This is reflected in the following statement by a FG respondent:

Well, there are a lot of people who do have that [kind of faith to believe in healing], but that doesn't mean that your faith is better than mine . . . it's just a different level . . . in that journey of where you go with the faith and your spirituality.

These spiritual life journeys, as well as the spiritual connections that women reported, varied on an individual basis and fluctuated over time.

Connection to God/higher power

The most common theme discussed by women in FGs and the individual interviews was having a relationship with or a connection to God, a higher power, and spirit or spiritual being. Some women reported being connected to God, Jesus, or to the Holy Spirit. For example, Sandra described that “It's [spirituality is] like God is touching you.” One FG respondent shared, “Spirituality means, your connection with God—Your time with God.” Women also discussed the concepts of transcendence and self-transcendence relative to their connection with God or a higher power. This is evident in the following FG narrative excerpt:

When I think of spirituality—I think of my spirit, I think of God and I think about what I believe in—my belief in God. To me spirituality is the ability to step out of yourself and just become one with God.

Overall, these statements summarize participants’ beliefs about the meaning of spirituality as connectedness to one's spiritual self and to God.

HIV/life events brought me closer to God

This subtheme emerged across the FGs and interviews. Although this subtheme is not necessarily a definition of spirituality, it offers a description of the women's spiritual trajectories and connection to God and their interpretation of the meaning of their individual spirituality. Most of the women described how their spiritual beliefs, practices, or experiences changed as a result of their HIV and they discussed becoming closer to God as a result of their HIV disease or other life events. Rachel shared, “I went to church before I became positive . . . So, I was always spiritual. It's just that now, as I grew older, my spirituality is more deeper now.” Similarly, Leah shared that although she was “brought up a believer,” she did not “become spiritual until after the fact [her HIV diagnosis].” This particular statement does not offer a clear differentiation between being spiritual and being “a believer”; however, the term implies having a set of [religious] beliefs, which does not inherently imply spiritual behavior. Sandra described drawing closer to God almost 10 years after her HIV diagnosis.

But it took back in, I say 1997 [diagnosed in 1988], to realize the mistake that I had made. And that's when I got closer to God. I gave up the drugs. I gave up everything, I got closer to God.

Lois described becoming more spiritual and getting closer to God while in prison:

After I became HIV, I wasn't even thinking about spirituality. I still wasn't spiritual—because I did like 2 years in prison before I got my spirit back . . . majority of the time I was in prison I was in lock down. And I needed to be locked down so I could really get close to God.

One FG respondent said, “It was the HIV that gave me something that I could not fight by myself, I could not control by myself, it brought me closer to God.” Some of the women said that HIV and the associated struggles and health issues awakened them. For example, one FG respondent said, “It's not so much that God wanted us to get HIV, but—Sometimes you need something to wake you up, and it woke me up.” Another FG respondent said, “But once I got [HIV] positive, it just seems as though, that my relationship with God has gotten closer.”

Theme 1 and its two related subthemes and supporting excerpts provide a description of what spirituality means to HIV-positive AA/Black women, including their perception of spirituality as a process or journey, which largely involves an individual's connection to God, a higher power, or an internal or external spiritual being or force (i.e., “ my spirit,” holy spirit).

For majority of the participants, a diagnosis of HIV or other significant life event resulted in an examination of, reflection on, or change in their spirituality—often an increase in their spirituality or perceived closeness to God. To some extent, HIV and other stressful life events increased these women's spiritual awareness or awakening, created a spiritual need (a desire to be closer to God), and motivated or drove them to locate meaning. Spirituality provided many of these women with lens through which they could review their lives and live with HIV.

Use of Spirituality/Spiritual Experiences

Two main themes exist within this category: (a) expressions of spirituality and (b) benefits of spirituality/a relationship with God provides. Participants described three subthemes of how they used, expressed, or exercised their spirituality. Women discussed four (subthemes) benefits or provisions of their spirituality or relationship with God.

Theme 2: Expressions of Spirituality

Across FGs and interviews, the most common spiritual experiences and modes of spiritual expression included church attendance, prayer, meditation, reading spiritual material or text (i.e., Bible), helping and encouraging others, being thankful, and testifying about God.

Religion and church/church attendance

Some participants discussed religion, church attendance, and religious programs or media as part of their spirituality. When specifically asked, participants described religion as “the gathering of people,” “just a label,” “a way of life,” and “a belief.” Religion was also discussed in the context of religious denominations (i.e., Christian, Catholic, and Baptist). Church was a common theme that was discussed by women in FGs and the interviews as an important part of their spirituality and spiritual expression, including belonging to a church, listening to sermons or participating in services at church or on TV, including praying, singing, and so on. Church attendance was also referred to as a means of communication with God. Rachel said, “I'm scared to go to sleep now in church ‘cause I don't want to miss nothing. I don't want to miss the message, ‘cause God might be trying to tell me something.’” The word church had shared and varied meanings among women. One woman described church as God's house and its symbolic representation. She said,

This is God's House, and coming into the church—the physical edifice itself, the building—it kind of makes it something you can see—OK— cause we can't—we see God—I see God in the trees, in the clouds and all of those things.

One woman said that part of spirituality is worshipping “with people of like minds.” Another woman said,

I thought that I could serve God at home, but the bible said forget not the gathering of my saints, and . . . worship him in spirit and in truth. So that means that you go to church and you pray.

Overall, although women described religion and church attendance as part of their spirituality, the degree of religious involvement or attendance varied and some of the women also expressed concerns about disclosure of HIV status in a church setting due to fear of or experiences with HIV-related stigma.

Prayer

Prayer was the single most common practice described in the individual interviews. Five of the six women talked about their frequent (daily or nearly daily) engagement in prayer and saying “grace” before meals as a means of communicating to God. One woman in FG 1 said, “I thank God that we can meditate and pray and all of these things, to help us get to where he wants us to be.” One woman in FG 2 summarized the spiritual practices discussed. She said, “I got my bible . . . when I feel like reading, I read, and I meditate . . . I just thank God.” Some women spoke about praying/meditating on particular scripture (i.e., 23rd Psalm).

Helping others

Many of the women discussed helping, doing for, and being there for others as means of expressing their spirituality. Lois shared, “Being there for the next person. Reaching out to them, touching their hearts, let them know that they're not alone.” Leah talked about wanting to be seen as “a servant in the eyes of Christ to do humanitarian things, like Coretta Scott King.” Another woman shared, “I don't go to church enough to give my tithes, but I do try to send a check or something to feed the hungry or something like that—do it that way, and by helping others.” Two women in FG 1 discussed helping others as being a spiritual “calling” to help people who faced similar challenges like the ones they faced. Some of them explained that it was a way for them to give back or make a difference in someone else's life.

Being thankful and testifying

The women in the groups often spoke of being thankful to God (for life, health, everything) and about testifying to others about HIV or about what God has done for them. Most of the women expressed gratitude for physical health. One woman in FG 2 said, “Lord knows I need to be thanking him for everything. My T cells are 1030 . . . I think I'm doing pretty good and I thank God everyday for what he's done for me.” One woman testified of her gratitude,

Maybe now today I can go and—testify about it—but I know he's real—I know, without a shadow of a doubt, . . . sometimes I can just lay there and think about the things that have happened to me and what could have happened, and I just have to thank God.

A woman in FG 1 listed all that she was thankful for:

I thank God for all my blessings, my medication, being back in good health, having healthy T-Cells, being non-detectable and all that—I just thank God for life . . . I thank God for taking that taste [of crack] out of my mouth.

Despite the many challenges they faced, all of the women expressed gratitude.

Having faith/belief in God

This theme emerged from five of the six individual interviews. Women described the practice of having faith in God, trusting God, or believing in God's abilities as an essential part of their spirituality. One woman said, “If they [people] would learn to give it to God—and trust him—and have faith, and educate and advocate and adhere to these things, they could live a long life.” Leah shared that a life without God is unimaginable, “I'm a strong believer in God . . . I just can't see my life doing anything—not even accomplishments . . . whatever I go through—I'm not going through it alone.” “Having faith” is a central tenet of Christianity, which is described extensively throughout the Bible (i.e., Hebrews 11), including various examples and may refer to trust or confidence in God (and His abilities).

Theme 3: Benefits of Spirituality/A Relationship With God Provides

Many of the women discussed the benefits they perceived or received in association with their spirituality and/or relationship with or connection to God. The most common provisions or benefits described by women in both groups were inner peace, improvement in health, or the experience of healing, strength, and the ability to “keep going.”

Health/healing

Several of the women discussed the concept of healing and their belief in God's ability to heal them. This theme emerged as a main theme in the individual interviews and all six of the women discussed an improvement in health related either to their spirituality, their connection to God, or as with one woman, her connection to others. Brenda described God as a “healer.” Sandra said, “My spiritual belief is that God will heal everything that's going on . . . my virus. I give it to Him.” Leah also explained that God restored her health and helped to deliver her from drug addiction. Like many of the women, one woman in FG 1 said,

Because of God's grace I am healed from diseases and addiction . . . I wouldn't be able to . . . 4 years free from drugs and alcohol, if it wasn't for Jesus—so it, it's just a lot of things, to graduate college, and be in college again and to get the T-Cells up to 1030, from 8 to 1030?

One woman attributed her recovery from a near-death experience to God and said,

I stand today, diagnosed in ’88, . . . had PCP, I almost died, with 12 T-Cells, now I have 1015 T-Cells, and I've been undetectable since ’96, so I know it ain't nothing but the father, son and the holy ghost!

Many women also specifically attributed their improved health to the integration of their spirituality with medications, treatments, and care from medical providers. One woman discussed how prayer helped her adhere to her HIV medication regimen, which resulted in a significant increase in her T-cell count from one to “seven hundred and something.” A woman in FG 1 discussed how having a connection to others improves health: “The support that we give to one another, helps to bolster our health, and that helps to bring up the immune system, you know—that's a part of that—that healing. OK, and that's what spirituality teaches us.” A woman in FG 1 summarized her review of studies on spirituality and health: “And there have been studies based on the ones that did have spiritual connections and those that didn't have it—the ones that didn't have it didn't do well, and we are here, we're doing well.” One woman in FG 2 explained that, overall, spirituality benefited her life. She said,

When I did begin to embrace spirituality and, and set some parameters in my life, and beliefs and principles, my life has been more fruitful and more whole and more fuller, and, and more of . . . a path, not just a wandering aimlessly.

Women also discussed that God works through others to help them or to heal them. One woman said,

Well . . . I'd be a fool to not know that God anointed doctors and medications to treat me . . . I'd be a fool not to believe in that, because I know he inspired people to take care of me—but still I say that I'm healed.

Inner peace, strength, and the ability to keep going

This was a main theme across FGs only. One woman in FG 2 shared some of the outcomes of spirituality she experienced, including “finding an inner peace.” Similar to other women, one woman in FG 1 shared, “It [spirituality] keep us strong, . . . keeps me going.” This woman also implicitly discussed the hope that her spirituality gives her in having “something to look forward to.” Another woman in FG 1 discussed hope more explicitly and said, “Part of spirituality is having hope . . . I also have hope for the day that I can sit at the table and say, yeah, I got my 1800 T-Cells back and so, I'm just like normal again.” Women also reported being strengthened by their spirituality and their connection with God. One woman in FG 2 shared, “I wouldn't be able to do this today, without, spirituality, without a relationship with my heavenly father, because I'm daily renewed, I'm daily cleansed, I'm daily strengthened.” In spite of the difficulties that the women in the groups endured, most of the women shared their belief that they were blessed (by God). One woman shared, “We are special people, we are chosen, he [God] couldn't use everybody, this virus, because they couldn't deal with it . . . when you think about it, we're blessed to be a blessing.”

Support

Many women spoke about the spiritual support they received. God was the most commonly described source of support and women described leaning on God during times of struggle. Some women described church, FGs, or support groups as examples of a safe place, and one woman described the use of affirmations, such as, “My God is greater than HIV” to “hold on to” for support. Rachel shared her experience with God as the main source of support in her life: “If it were not for my faith, I don't know where I'd be. I have to rely . . . I had to catch hold to God, because I couldn't catch hold to nothing else.” Leah shared that her life strongly depends on support from God: “I've had so many spiritual encounters that my life is nothing without relying on—my higher power, which is Jesus.” A woman in FG 2 also discussed God and her congregation as sources of support. Additional sources of support discussed included religious leaders, church communities, friends, or other people with HIV, or mental health support received from therapists, counselors, or support groups, and family (for few women).

Here for a reason or purpose: A second chance

Having or finding purpose in life was a major theme for participants and having a second chance was a subtheme for many participants. This theme emerged across FGs and four interviews, and was discussed in terms of remaining in existence, in spite of being HIV-positive and trusting that there was some reason or purpose for their “being here.” Some also discussed having a purpose for their HIV diagnosis. Some women expressed what they believed to be the reason/purpose, but others shared that they were uncertain or unaware of what the reason/purpose was. Many of the women stated or implied their belief that God had a reason/purpose for their lives. Sandra discussed her perspective on why she had HIV. She said, “Well, God gave me this for a reason to slow me down, to make me understand what's what and what He's going through and in order for me to know.” A woman in FG 2 acknowledged not knowing what her specific purpose in life was. She said, “I'm surviving. I'm here for a reason and that reason is . . . right now, I don't know, but I'm here for a reason.” Another woman in FG 2 discussed how she had survived many dangerous situations and diseases because God had a purpose for her life. She said, “God created me in his likeness and there was a reason that, he wanted me to live” A woman in FG 1 shared, “It's my faith that makes me believe that God kept me here for a purpose,” despite everything she had done and experienced.

Some women in the individual interviews discussed being given a “second chance” by God after an HIV diagnosis. Brenda shared, “He knew there was a better side to me. So He allowed me and gave me a chance to get my life right.” Rachel shared, “To me it's just like I get a second chance. Grace, to me, means I get another chance! . . . and I thank Him, for giving me another chance.” Leah shared, “[God] had mercy on me and he spared me . . . he said to me and those doctors, ‘ . . . I'm giving her a second chance.’”

To summarize, participants’ discussions included descriptions, definitions, expressions, and benefits of spirituality, religion, church, God and his provisions, and relations between spirituality and perceptions regarding their mental and physical health. In general, women described spirituality as a relationship or connection with God or higher power, a belief or discipline, as helping others, having hope, and as a person's spirit within. Few women also discussed a connection or relationship to others. Two participants, one from each FG, discussed the concept of self-transcendence, which refers to moving or focusing beyond one self. The most common expressions of spirituality discussed were prayer, church attendance, helping others, reading spiritual material, and being thankful. Women discussed the benefits of improved health and well-being, inner peace, spiritual support, and finding meaning and purpose from their relationship with God. Women in the interviews expressed their beliefs and gratitude about being given a second chance at life in spite of their HIV status. The one participant who reported having no belief in God also discussed many of the prevailing themes, including the importance of a connection to others, being thankful, helping others, social support, and a second chance.

Discussion

The findings are framed in light of the work of Viktor Frankl (1962), theorists, psychologists (Park, 2010), and results from past studies on spirituality, meaning, purpose in life, and well-being. Frankl proposed that the primary force driving all human beings is the desire to find purpose in life, and that purpose is specific to the individual and arises from the circumstances of that person's immediate life. Similarly, psychologists and theorists highlight the importance of meaning making as individuals confront highly stressful life experiences (Park, 2010). For many of the women in this study, the diagnosis of and living with HIV served as a driving force for them to locate meaning and purpose in their individual lives and also stimulated a spiritual awakening or awareness. Similarly, nursing theorists Betty Neuman (1989) and Jean Watson (1985) asserted that people have a basic goal to actualize the real self and develop their spiritual essence or spiritual awareness (Barnum, 1996).

Women with HIV in this study defined their spirituality in relation to God, a higher power or spiritual being. This finding is consistent with the work of nurse theorists Leininger (1995), Neuman (1989) and Watson (1985) regarding persons’ spiritual and holistic nature and relation to God or a higher power, which has also been reported among PLWH (Guillory et al., 1997; Tarakeshwar et al., 2006). Women with HIV express their spirituality in various ways, and in this study, most commonly through prayer, and also by helping others, and a few women discussed meditation in the context of reading the Bible. These findings may suggest that private spiritual practices, such as these and activities such as helping others may be more essential to the spiritual lives of some women with HIV and might reveal some greater significance about the spirituality of some AA women living with HIV. Prayer and meditation are common practices reported among women with HIV (Guillory et al., 1997; Somlai et al., 1998; Tarakeshwar et al., 2006) in addition to reading the Bible (Somlai et al., 1998; Tarakeshwar et al., 2006). Others have also reported an increase in women's practice of prayer and/or meditation since diagnosis with HIV (Guillory et al., 1997). Kindness to others and helping or giving to others are additional spiritual expressions among women with HIV/AIDS (Coward, 1995; O'Connell & Skevington, 2005), which may also help them find meaning and purpose in their lives (Coward, 1995).

Spirituality was described by the women as a process that occurred over variable time periods and as a journey varying spirituality experiences and spiritual growth. As part of their spiritual growth, most women described disconnections in their relationship with God or church, but most women experienced a turning point in their spiritual journeys that brought them back. For many, this turning point was the diagnosis of HIV or the associated struggles and stressors that often lead many to rely on sources greater than themselves or those readily available to them. Similar to the findings of other studies, many of the women in this study shared that HIV and or stressful life events brought them closer to God. The literature suggests that for many PLWHA, an HIV-positive diagnosis triggers them to engage in spiritual reflection in attempt to find meaning in life and may bring them closer to God (Arnold et al., 2002; Hall, 1998; Tarakeshwar et al., 2006) and increase their church attendance or spirituality (Guillory et al., 1997; Siegel & Schrimshaw, 2002; Tarakeshwar et al., 2006). According to Hall (1998), study findings among PLWHA suggested that after a crisis that threatens health, people question and become open to discover their unique spiritual meaning and engage in spiritual growth. For AA HIV-positive women, in particular, the importance of religion may often stem from childhood because religion is generally a part of AA culture; however, living with HIV might have added to, renewed, or reframed spiritual importance in a more personal and meaningful way. According to Park (2010), people generally have global meaning and cognitive frameworks with which to interpret their experiences, but certain circumstances and stressful life events may motivate individuals to engage in meaning making efforts to restore a sense of the world as meaningful and their lives as significant or worthwhile. The authors believe that spirituality may provide some individuals with an additional framework with which to interpret their experiences and restore the discrepancy between global meaning and appraised meaning during stressful times (i.e., adjusting to the demands of living with HIV/AIDS). In light of Park's (2010) work, HIV-positive women in this study reported various types of “meanings made,” including a “sense of having ‘made sense’” (i.e., women reported knowing their life had a purpose even though they could not articulate that purpose), “growth or positive life changes” (including spiritual), “integration of stressful life events into identity” (living with HIV), and “restored or changed sense of meaning in life.”

Overall, findings from the study suggested that spirituality had a positive impact on the mental and physical health and overall quality of life of the women. This finding suggests that differences in participants’ spirituality and in their spiritual expression may have contributed to the variations in their perceptions of what they gained. Researchers have found that spirituality plays a significant role in sustaining mental wellness among HIV-positive black women (Braxton et al., 2007), serve as a strong source of guidance, healing, coping, peace, comfort, and protection during challenging times, especially among AAs (Newlin et al., 2002) and the “expression of emotion in Black churches offers an outlet for pent-up anguish” (Newlin et al., 2002, p. 59). Women discussed how their spirituality enhanced their immune function and life. Other researchers also found that some HIV-positive women described healing aspects of spirituality (Dunbar et al., 1998; Guillory et al., 1997). As in this study, women relied on God to provide spiritual and physical healing, but still accepted conventional medical treatment for their disease and believed that God could work through others to heal them (Guillory et al., 1997). This finding extends the literature in this area regarding the role of spirituality in and patients’ personal integration of spirituality with HIV care. This study confirmed the findings of others that women with HIV describe inner peace in relation to God (Guillory et al., 1997; O'Connell & Skevington, 2005) and hope as important benefits or aspects of spirituality and meaning (Coward, 1995).

In this study, women living with HIV reported varying sources of support, including friends or others with HIV (social), counselors (mental), and God or clergy (spiritual), to help them cope with their struggles and with HIV, but God (spiritual) was the main resource for majority of the women. Spirituality provides many perceived benefits, including spiritual support (Siegel & Schrimshaw, 2002), social support (Peterson, Johnson, & Tenzek, 2010; Siegel & Schrimshaw, 2002), and emotional support (Peterson et al., 2010; Siegel & Schrimshaw, 2002). For many of these economically impoverished women, God may be seen as a readily available, free, accessible source for them to connect to at will. Overall, people living with HIV report receiving support from God, friends, or others with HIV (Dunbar et al., 1998; Tarakeshwar et al., 2006). Conversely, family members may also serve as a source of strain and struggle for women living with HIV (Tarakeshwar et al., 2006). Although families were influential factors for the development of spirituality during childhood, it was evident that as the women grew older their personal experiences shaped their spirituality. The lack of support from family may have required some of the women to seek support from other resources, including God, clergy, friends, and counselors.

Overall, women in this study were able to find meaning and purpose in their lives, which enabled some to redefine their self-concept and the meaning of their illness, especially because they survived HIV when many they knew did not. This finding supports Frankl's (1962) work regarding humans’ desire to find purpose in life, which often arises from the circumstances of that person's immediate life, such as living with HIV/AIDS—a stigmatized and life-threatening chronic disease. The women placed more emphasis on having a purpose for God sparing their life than on being able to articulate a specific purpose. Other researchers also found that participants, including PLWH, reported finding purpose as a significant part of their life (Dunbar et al., 1998; Hall, 1998; Mattis, 2002; O'Connell & Skevington, 2005; Tarakeshwar et al., 2006) and women with HIV found purpose by reviewing their lives and educating others about HIV (Dunbar et al., 1998). Many of the women in the individual interviews discussed being given a second chance at life by God despite engaging in risky behaviors and having HIV disease. This is a fairly novel finding that extends the literature in this area previously discussed on purpose in life among PLWHA. They shared how their diagnosis and redefined spirituality helped them to reassess and shape their lives and lifestyles in more positive ways. Overall, findings unique to women in this study indicate the powerful influence of their context, individual characteristics, and beliefs. These context variables include exposure to spirituality as a young person, struggles in life, sociocultural beliefs about spirituality and its importance, the influence of family, community and AA culture, and the belief that their spirituality provided them with improved health, healing and a second chance in life despite a once life threatening, and terminal illness.

This study had a small sample size consistent with that of similar qualitative studies and the authors believe that the sample size and methods sufficiently achieved saturation. This study has limited applicability of the findings mostly to AA women with HIV/AIDS who identify as spiritual. However, the findings remain with particular relevance as the study was conducted in the southeastern United States, which is informally considered by many as the “bible belt,” due to high rates of church attendance and religious identification, on average (Koenig, 2004), which is reflected in the American Religious Identification Survey (Kosmin & Keysar, 2009).

These findings highlight the meaning, importance, and role of spirituality among HIV-positive AA women and the varied ways in which they experience and express spirituality. This study describes how predominantly Christian HIV-positive AA women frame their lived spiritual experience while living with HIV/AIDS. It also provides unique information about the perceived role of spirituality in their health and healing. This is particularly relevant and important to consider in the care of women with HIV, especially among AA HIV-positive women for whom religion and spirituality often play an important role in managing stress and maintaining overall well-being in their daily lives. This information can serve as a complementary framework to help health care providers realize the uniqueness of their spirituality and support needs such that (a) private religious practices, including prayer and religious TV, radio, or music may sometimes be more relevant than church attendance; (b) God (or a connection to others) is seen as an important and complementary factor in health; and (c) family may serve as, but is not always, a primary source of support. Nurses and other health care providers should assess HIV-positive patients’ spiritual needs and the degree to which they would like to have spiritual or religious factors incorporated into their care. Depending on patients’ preferences, this could entail (a) allotting time in the care schedule and privacy for a patient to be undisturbed during activities such as prayer, reading, meditation; (b) collaborating with the chaplain or pastoral care team or assisting the patient to contact a leader or someone from her religious institution; (c) helping the patient to involve family and loved ones in the plan of care to provide spiritual and nonspiritual support; and (d) continuing to intentionally provide a caring, nonjudgmental health care climate.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the following National Institutes of Health and National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) Grants: 1 R01 NR008094-01A1 RSUM (Dalmida), NRSA F31NR009758-01 (Dalmida), R01 NR04857 (GBL Study, DiIorio, PI), and R01 NR008094 (KHARMA Project, Holstad, PI).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflict Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abeles R, Ellison C, George L, Idler E, Krause N, Levin J, Williams D. Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. Fetzer Institute; Kalamazoo, MI: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold R, Avants SK, Margolin A, Marcotte D. Patient attitudes concerning the inclusion of spirituality into addiction treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:319–326. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnum BS. Spirituality in nursing: From traditional to new age. Springer; New York, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth HB. The importance of spirituality/religion and health-related quality of life among individuals with HIV/AIDS. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(Suppl. 5):S3–S4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braxton ND, Lang DL, Sales JM, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The role of spirituality in sustaining the psychological well-being of HIV-positive Black women. Women & Health. 2007;46:113–129. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson VB, Green H. Spiritual well-being: A predictor of hardiness in patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Journal of Professional Nursing. 1992;8:209–220. doi: 10.1016/8755-7223(92)90082-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester DN, Himburg SP, Weatherspoon LJ. Spirituality of African-American women: Correlations to health-promoting behaviors. Journal of National Black Nurses Association. 2006;17:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Kahn D, Steeves R. Hermeneutic phenomenological research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman CL, Holzemer WL. Spirituality, psychological well-being, and HIV symptoms for African-Americans living with HIV disease. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 1999;10:42–50. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward DD. The lived experience of self-transcendence in women with AIDS. JOGNN Clinical Studies. 1995;24:314–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1995.tb02482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coward DD, Reed PG. Self-transcendence: Resource for healing. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1996;17:275–288. doi: 10.3109/01612849609049920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmida SG. Spirituality, mental health, and health-related quality of life among women with HIV/AIDS: Integrating spirituality into mental health care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2006;27:185–198. doi: 10.1080/01612840500436958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmida SG, Holstad MM, DiIorio CK, Laderman G. Spiritual well-being, depressive symptoms, and immune status among women with HIV/AIDS. Women Health. 2009;49(2-3):119–143. doi: 10.1080/03630240902915036. PMID: 19533506: PMC2699019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmida SG, Holstad MM, DiIorio CK, Laderman G. Spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life among African American women with HIV/AIDS. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2010;4:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11482-010-9122-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln Y. Handbook of qualitative research. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar HT, Mueller CW, Medina C, Wolf T. Psychological and spiritual growth in women living with HIV. Social Work. 1998;43:144–154. doi: 10.1093/sw/43.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CW. Spiritual well-being: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Psychology & Theology. 1983;11:330–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CW, Paloutzian RF. Loneliness, spiritual well-being and the quality of life. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. Wiley-Interscience; New York, NY: 1982. pp. 224–237. [Google Scholar]

- Emblen J. Religion and spirituality defined according to current use in nursing literature. Journal of Professional Nursing. 1992;8:41–47. doi: 10.1016/8755-7223(92)90116-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa LR, Davis B, Baker S, Bunch JB. The influence of spirituality on health care-seeking behaviors among African Americans. Association of Black Nursing Faculty Journal. 2006;17:82–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE. Man's search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. Beacon; Boston, MA: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Freidmann M, Mouch J, Racey T. Nursing the spirit: The framework of systemic organization. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;39:325–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryback PB, Reinert BR. Spirituality and people with potentially fatal diagnoses. Nursing Forum. 1999;34:13–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.1999.tb00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger JN, Appel SJ, Davidhizar R, Davis C. Church and spirituality in the lives of the African American community. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2008;19:375–383. doi: 10.1177/1043659608322502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg B. Connection: An exploration of spirituality in nursing care. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;27:836–842. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillory JA, Sowell R, Moneyham L, Seals B. An exploration of the meaning and use of spirituality among women with HIV/AIDS. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 1997;3:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase JE, Britt T, Coward DD, Leidy NK, Penn PE. Simultaneous concept analysis of spiritual perspective, hope, acceptance, and self-transcendence. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1992;24:141–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1992.tb00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BA. Patterns of spirituality in persons with advanced HIV disease. Research in Nursing & Health. 1998;21:143–153. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199804)21:2<143::aid-nur5>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, McClure SM. Perceptions of the religion-health connection among African American church members. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16:268–281. doi: 10.1177/1049732305275634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H. Religion, spirituality, and medicine: Research findings and implications for clinical practice. Southern Medical Journal. 2004;97(12):1194–1200. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146489.21837.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Cohen HJ. The link between religion and health: Psycho-neuroimmunology and the faith factor. Oxford; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, George LK, Titus P, Meador KG. Religion, spirituality, and acute care hospitalization and long-term care use by older adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164:1579–1585. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmin BA, Keysar A. American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS 2008): Summary report. Trinity College; Hartford, CT: Mar, 2009. 2009. Retrieved from http://www.americanreligionsurvey-aris.org/reports/ARIS_Report_2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 3rd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger M. Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, research and practices. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Litwinczuk KM, Groh CJ. The relationship between spirituality, purpose in life, and well-being in HIV-positive persons. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2007;18:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz KA, Hays RD, Shapiro MF, Cleary PD, Asch SM, Wenger NS. Religiousness and spirituality among HIV-infected Americans. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8:774–781. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS. African American women's definitions of spirituality and religiosity. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis JS. Religion and spirituality in the meaning-making and coping experiences of African American women: A qualitative analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2002;26:309–321. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DP, Holder B, Wetsel MA, Cawthon TA. Spirituality and HIV disease: An integrated perspective. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2001;12:58–65. doi: 10.1016/s1055-3290(06)60144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSherry W, Draper P. The debates emerging from the literature surrounding the concept of spirituality as applied to nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;27:683–691. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Thoresen CE. Spirituality, religion, and health. American Psychologist. 2003;58:24–35. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller PS, Plevak DJ, Rummans TA. Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: Implications for clinical practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2001;76:1225–1235. doi: 10.4065/76.12.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman B. The Neuman systems model. 2nd ed. Appleton and Lang; Norwalk, CT: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Newlin K, Knafl K, Melkus GD. African-American spirituality: A concept analysis. Advances in Nursing Science. 2002;25:57–70. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200212000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan P, Crawford P. Towards a rhetoric of spirituality in mental health care. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;26:289–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997026289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien ME. Spirituality in nursing: Standing on holy ground. 2nd ed. Jones and Bartlett; Boston, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell KA, Skevington SM. The relevance of spirituality, religion and personal beliefs to health-related quality of life: Themes from focus groups in Britain. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10:379–398. doi: 10.1348/135910705X25471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:257–301. doi: 10.1037/a0018301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Johnson MA, Tenzek KE. Spirituality as a life line: Women living with HIV/AIDS and the role of spirituality in their support system. Journal of Interdisciplinary Feminist Thought. 2010;4(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Plattner IE, Meiring N. Living with HIV: The psychological relevance of meaning making. AIDS Care. 2006;18:241–245. doi: 10.1080/09540120500456227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polzer Casarez RL, Miles MS. Spirituality: A cultural strength for African American mothers with HIV. Clinical Nursing Research. 2008;17:118–132. doi: 10.1177/1054773808316735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post SG, Puchalski CM, Larson DB. Physicians and patient spirituality: Professional boundaries, competency, and ethics. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2000;132:578–583. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-7-200004040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE. Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist. 2003;58:36–52. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed P. An emerging paradigm for the investigation of spirituality in nursing. Research in Nursing & Health. 1992;15:349–357. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridge D, Williams I, Anderson J, Elford J. Like a prayer: The role of spirituality and religion for people living with HIV in the UK. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2008;30:413–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin H, Rubin IS. Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Scarinci EG, Griffin MTQ, Grogoriu A, Fitzpatrick JJ. Spiritual well-being and spiritual practices in HIV-infected women: A preliminary study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Dubin FL, Seeman M. Religiosity/spirituality and health: A critical review of the evidence for biological pathways. American Psychologist. 2003;58:53–63. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Schrimshaw EW. The perceived benefits of religious and spiritual coping among older adults living with HIV/AIDS. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41:91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Martone MG, Kerwin JF. Spirituality and psychosocial adaptation among women with HIV/AIDS: Implications for counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Somlai AM, Heckman TG, Hackl K, Morgan M, Welsh D. Developmental stages and spiritual coping responses among economically impoverished women living with HIV disease. Journal of Pastoral Care. 1998;52:227–240. doi: 10.1177/002234099805200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell R, Moneyham L, Hennessy M, Guillory J, Demi A, Seales B. Spiritual activities as a resistance resource for women with human immunodeficiency virus. Nursing Research. 2001;49:73–82. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakeshwar N, Khan N, Sikkema KJ. A relationship-based framework of spirituality for individuals with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:59–70. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuck I, Thinganjana W. An exploration of the meaning of spirituality voiced by persons living with HIV disease and healthy adults. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2007;28:151–166. doi: 10.1080/01612840601096552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. Nursing: Human science and human care: A theory of nursing. Appleton-Century-Crofts; Norwalk, CT: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Woods TE, Ironson GH. Religion and spirituality in the face of illness. Journal of Health Psychology. 1999;4:393–412. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]