Summary

Psychiatric disorders may be more common in burn-injured subjects than in the general population, and oftentimes contribute to the injury itself. Even in the absence of underlying psychiatric illnesses, burn patients may still benefit from a psychiatric evaluation during and after their hospitalization. In this regard, we included a dedicated psychiatry service in our multidisciplinary burn team. We review herein the course of burn patients that were offered psychiatric evaluation and highlight the benefits of such a program. We conducted an IRB-approved retrospective chart review of burn subjects admitted to our institution between June 15, 2009 and April 30, 2010 and identified 83 patients that were examined by our psychiatrist. Indications for consultation, history of psychiatric illness and substance abuse, as well as administered drugs, were recorded. Among the 83 evaluated patients, 48 (57.8%) had a preexisting psychiatric disorder and 36 (43.4%) suffered from substance abuse. The most common indications for consultation were pain (28.1%), alcohol dependence (25.8%), anxiety (24.7%), illicit drug abuse (16.8%), depression (15.7%), post-traumatic stress disorder (8.9%), and sleep disturbances (8.9%). Pharmacotherapy was initiated in 75 patients (90.3%). 31 (37.3%) had neither a psychiatric disorder nor a history of substance abuse, although 26 of them (83.9%) still received drugs for psychiatric conditions. The inclusion of a dedicated psychiatrist as part of our burn team has improved our comprehensive burn care. In the overwhelming majority of cases, even in the absence of preexisting psychiatric illnesses, consultation resulted in pharmacologic intervention and enhanced patient care.

Keywords: psychology, psychiatry, burn injury, burn service

Abstract

Les troubles psychiatriques peuvent être plus fréquents chez les patients brûlés que dans la population générale, et contribuent souvent à la blessure elle-même. Même en l’absence de maladies psychiatriques sous-jacents, les patients brûlés peuvent encore bénéficier d’une évaluation psychiatrique pendant et après leur hospitalisation. À cet égard, nous avons inclus un service de psychiatrie dédié à notre équipe multidisciplinaire pour la gestion des brûlures. Nous examinons ici les cours de patients brûlés à qui une évaluation psychiatrique a été proposée et nous mettons en évidence les avantages d’un tel programme. Nous avons effectué un examen rétrospectif - approuvé par les CPP - des patients brûlés admis dans notre institution entre le 15 Juin 2009 et le 30 Avril, 2010, à partir de lequel nous avons identifié 83 patients qui ont été examinés par notre psychiatre. Nous avons enregistré les indications pour la consultation, les antécédents de maladie psychiatrique et la toxicomanie, ainsi que les médicaments administrés. Parmi les 83 patients évalués, 48 (57,8 %) avaient un trouble psychiatrique préexistante et 36 (43,4%) a souffert de l’abus de substances. Les indications les plus fréquentes de consultation étaient la douleur (28,1%), la dépendance à l’alcool (25,8%), l’anxiété (24,7%), l’abus de drogues illicites (16,8%), la dépression (15,7%), les troubles de stress post-traumatique (8,9%), et troubles du sommeil (8,9%). La pharmacothérapie a été instaurée dans 75 patients (90,3%). 31 (37,3%) ne présentaient pas de troubles psychiatriques ni une histoire d’abus de substance mais quand même 26 d’entre eux (83,9 %) ont reçu des médicaments pour des troubles psychiatriques. L’inclusion d’un psychiatre spécialisé dans le cadre de notre équipe a amélioré notre système complet de soins aux brulés. Dans l’écrasante majorité des cas, même en l’absence des maladies psychiatriques préexistantes, la consultation a donné lieu à une intervention pharmacologique et a amélioré les soins aux patients.

Introduction

Psychiatric illness and substance abuse are well-described risk factors for burn injury.1-3 The treatment of burn patients with psychiatric illness is challenging as their hospital course is often complicated by withdrawal symptoms, agitation, delirium, and significant pain.4-6 Furthermore, studies have shown that preexisting psychiatric diseases are associated with delayed wound healing, an increase of surgical operations, prolonged hospital stay, and slower rehabilitation.7 For these reasons, a multidisciplinary approach to burn care, incorporating a psychiatric service, might be beneficial and could potentially improve patient outcomes.

Along these lines, in June 2009, a dedicated staff psychiatrist joined our Burn Service at the Sumner Redstone Burn Center. His main tasks consisted of assisting with inpatient management of pain, agitation, and delirium; directing the outpatient burn psychiatry clinic; and implementing/ coordinating an educational curriculum for medical students, residents, fellows (and other house staff members) centered on the role of psychiatry in burn care.

In this paper, we review our initial experience of this approach by evaluating the indications for psychiatric consultation, the treatments implemented by the psychiatric team, and highlight the benefits of incorporating a dedicated psychiatric service in a multi-disciplinary burn team.

Methods

We performed an IRB-approved retrospective review of all admissions to our Adult Burn Center (MGH Sumner Redstone) between June 15, 2009 and April 30, 2010. The Research Patient Data Registry, a centralized clinical database maintained by Partners Healthcare, was used to identify burn patients that were evaluated by our psychiatric service. Demographics as well as burn injury characteristics were extracted. These included age, gender, type of burn, total body surface area (TBSA) involved, history of psychiatric illness, history of substance abuse, indication for consultation, and pharmacologic intervention by staff psychiatrist.

Results

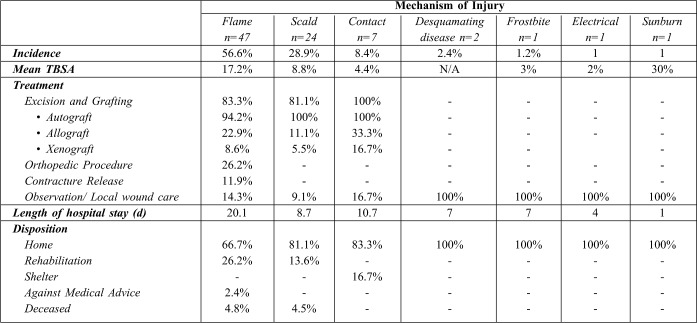

Between June 15, 2009 and April 30, 2010, a total of 344 patients were admitted to the Sumner Redstone Burn Center, of which 83 (24.1%) were evaluated by the staff psychiatrist. Of those evaluated, the mean age was 43.3 years (SD 12.9), and 59 patients (71.1%) were males. The most common mechanism of burn was flame injury (n=47/83, 56.6%), followed by scald injury (n=24/83, 28.9%). Table I presents the different mechanisms of injury along with their incidence, TBSA, length of hospital stay, as well as the different treatment plans and types of final disposition.

Table I. Characteristics of the burn-injured patients that received psychiatric evaluation.

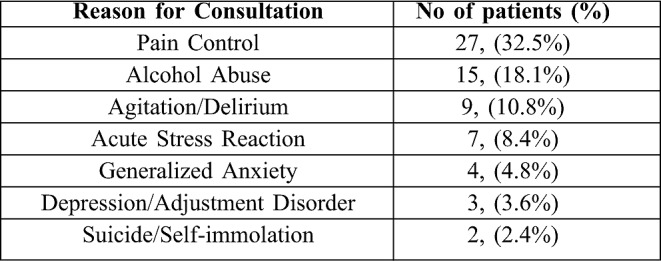

The most common indication for a psychiatric consultation was pain control (32.5%), followed by alcohol abuse (18.1%), and agitation/delirium (10.8%). Table II lists all indications. 21 patients (25.3%) had more than one indication for psychiatric evaluation; such patients suffered from both substance abuse and poor pain control.

Table II. Indications for consultation of the burn-injured patients that received psychiatric evaluation.

Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders

The prevalence of a preexisting psychiatric disorder among patients examined by our psychiatrist was 40.9% (n=34/83). 23 of them (67.6%) had a previous diagnosis of a mood disorder (16 had depression and 7 bipolar disorder). 9 patients (26.5%) had a previous diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), 4 (11.8%) had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and 1 (2.9%) obsessive- compulsive disorder (OCD). 4 patients (11.8%) had more than one diagnosis, with two suffering from both depression and GAD, and two others from depression and ADHD.

Prevalence of Substance Abuse

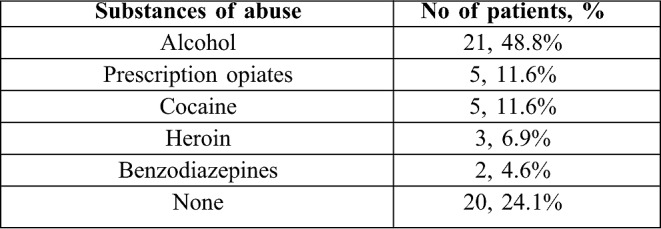

The prevalence of substance abuse in patients evaluated by our psychiatrist was 51.8% (n=43/83). Alcohol was in the lead (21 patients, 48.8%), followed by prescription opiates and cocaine (5 patients each, 11.6%). Table III shows the prevalence of the different abused substances. Concomitant psychiatric illness and substance abuse were present in 17 of the total 83 patients (20.4%).

Table III. Substance of abuse among the burn-injured patients that received psychiatric evaluation.

Pharmacologic Interventions

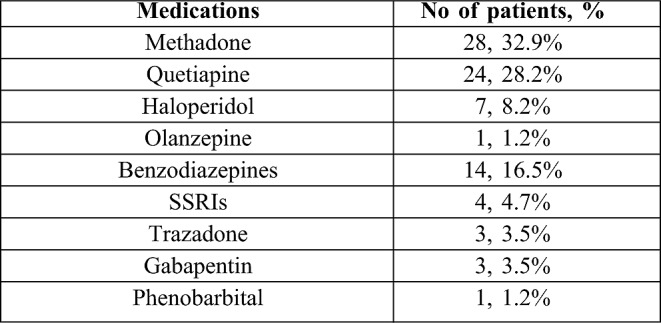

Pharmacologic therapy was recommended and initiated in 91.5% of all evaluated patients (n=76/83). Opiates for pain control came first, with methadone being the most prescribed drug (50% of patients). Dopamine antagonists, such as haloperidol and quetiapine, came second (58.9%). Benzodiazepines were third (25%), followed by serotonin modulators (12.5%). Approximately 80% of the patients were treated with multiple medications (i.e. from different pharmacologic classes). Table IV summarizes all prescribed drugs.

Table IV. Pharmacologic interventions initiated by psychiatric consultation.

Discussion

Over a ten-month period, our psychiatry service at the Sumner Redstone Burn Center evaluated 83 patients admitted for burn injuries. More than 50% of those had a history of substance abuse, close to 40% had a preexisting psychiatric disorder, and 20% had both. Previous studies demonstrated that such burn patients might suffer from delayed wound healing, prolonged hospital stay, and might even require more operations.8 Furthermore, recent studies suggested that psychological distress, even in the absence of a psychiatric history, can negatively impact burn recovery.9 Psychological distress might even contribute to an initial delay in seeking care and to poor compliance with treatment, potentially leading to a complicated hospital course. Despite these facts, the management of concomitant psychiatric illness and burn injury remains ill-defined in the available literature.

The most common indication for psychiatric consultation in this study was pain control. Methadone was frequently used in our burn center and patients were closely followed up after discharge. Patients with a history of substance abuse are known to suffer extensively from inadequate pain control.4 These patients should be identified early during their hospital course for a prompt psychiatric assessment. Agitation and delirium are also frequently encountered psychiatric conditions, particularly in the burn ICU and among elderly patients. These events seem to be particularly associated with pain.10 Pain remains a major problem in the burn ICU; it not only results from the burn and trauma themselves, but also from the multiple surgical and non-surgical procedures these patients frequently undergo.11,12 Moreover, a recent study found that opiates and methadone reduced the risk of developing delirium, whereas exposure to benzodiazepines seemed to trigger such state.13 In the event these conditions develop, close monitoring is warranted, and oftentimes a dopamine antagonist is required.14 In this study, pharmacologic therapy was started in all but four patients evaluated by our staff psychiatrist (91%).

Building on these results, our staff psychiatrist organized an educational program for medical students, residents, fellows, and midlevel providers who rotate on the burn service. Weekly didactic lectures are given covering a wide array of topics—including pain management, alcohol withdrawal, and delirium.

Conclusion

Major burn centers have evolved to provide a multidisciplinary approach to patient care in which psychiatry is an essential component. This approach proved to be beneficial to burn patients at our center. In addition to inpatient and outpatient psychiatric care, implementing an educational program highlighting the unique psychiatric needs of the burn population is of utmost importance. For further validation of our results, a prospective trial where burn-injured patients are randomized to either a psychiatric evaluation arm or a regular burn care arm is warranted; such trial needs to evaluate pertinent clinical outcomes (length of hospital stay, pain score, rehabilitation, cost, etc…) as well as the cost-effectiveness of such an approach.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest. None

References

- 1.Davydow DS, Katon WJ, Zatzick DF. Psychiatric morbidity and functional impairments in survivors of burns, traumatic injuries, and ICU stays for other critical illnesses: a review of the literature. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2009;21:531–8. doi: 10.3109/09540260903343877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kramer CB, Gibran NS, Heimbach DM, Rivara FP, Klein MB. Assault and substance abuse characterize burn injuries in homeless patients. J. Burn Care Res. 2008;29:461–7. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31817112b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salehi SH, As’adi K, Musavi J, Ahrari F, Nemazi P, Kamranfar B, Gaseminegad K, Faramarzi S, Shoar S. Assessment of substances abuse in burn patients by using drug abuse screening test. Acta Med. Iran. 2012;50:257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell AM, Dewey CM. Chronic pain in patients with substance abuse disorder: general guidelines and an approach to treatment. Postgrad Med. 2008;120:75–9. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2008.04.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown C, Albrecht R, Pettit H, McFadden T, Schermer C. Opioid and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome in adult burn patients. Am. Surg. 2000;66:367–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansbrough JF, Zapata-Sirvent RL, Carroll WJ, Johnson R, Saunders CE, Barton CA. Administration of intravenous alcohol for prevention of withdrawal in alcoholic burn patients. Am. J. Surg. 1984;148:266–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamolz L-P, Andel H, Schmidtke A, Valentini D, Meissl G, Frey M. Treatment of patients with severe burn injuries: The impact of schizophrenia. Burns. 2003;29:49–53. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tarrier N, Gregg L, Edwards J, Dunn K. The influence of pre-existing psychiatric illness on recovery in burn injury patients: The impact of psychosis and depression. Burns. 2005;31:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wisely JA, Wilson E, Duncan RT, Tarrier N. Pre-existing psychiatric disorders, psychological reactions to stress and the recovery of burn survivors. Burns. 2010;36:183–91. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gélinas C, Dasta JF, Davidson JE, Devlin JW, Kress JP, Joffe AM, Coursin DB, Herr DL, Tung A, Robinson BRH, Fontaine DK, Ramsay MA, Riker RR, Sessler CN, Pun B, Skrobik Y, Jaeschke R. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:263–306. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Availability of clinical practice guidelines on Acute Pain Management: Operative or medical procedures and trauma and urinary incontinence in adults-AHCPR. Fed. Regist. 1992;57:12829–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puntillo KA, White C, Morris AB, Perdue ST, Stanik-Hutt J, Thompson CL, Wild LR. Patients’ perceptions and responses to procedural pain: Results from Thunder Project II. Am. J. Crit. Care. 2001;10:238–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agarwal V, O’Neill PJ, Cotton BA, Pun BT, Haney S, Thompson J, Kassebaum N, Shintani A, Guy J, Ely EW, Pandharipande P. Prevalence and risk factors for development of delirium in burn intensive care unit patients. J. Burn Care Res. 2010;31:706–15. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181eebee9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown RL, Henke A, Greenhalgh DG, Warden GD. The use of haloperidol in the agitated, critically ill pediatric patient with burns. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17:34–8. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]