Strapline: Sequencing of the second genome of Mycobacterium leprae and the development of a genome-wide typing scheme has of has provided deeper understanding of the evolution and epidemiology of the leprosy bacillus. This study confirms that leprosy has a single clone origin and has spread around the globe following human migration and trade over the last several thousand years.

Leprosy has affected humans for at least 4,000 years1, with accounts of leprosy-like illnesses widespread though various cultures over many centuries. Once of global distribution, leprosy is now a curable infectious disease that nevertheless remains a major public health problem in Africa, Asia and, especially, South America. Attempts at global eradication are on-going with the WHO recently adopting a ‘final push’ strategy2. Despite its prominence and long history, many aspects of the biology of leprosy remain poorly understood, in large degree because the causative organism, the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae, remains uncultivable on artificial media. Advances have been slow and hard won3, but in recent years the application of molecular genetics has made a major contribution to our understanding, particularly the sequencing of the complete genome of the M. leprae TN strain in 20014. This showed that the M. leprae genome was appreciably smaller than its nearest sequenced relative, M. tuberculosis (by about 1MB, or 25% of the genome), and that about half of the genome comprised inactivated pseudogenes. On pgs 1282 - 1289 of this issue, Stuart Cole and colleagues5 now report the second complete M. leprae genome sequence, that of a Brazilian strain Br4923, as well as high coverage sequencing of two additional strains and genome-wide analysis of sequence variation in a set of geographically diverse samples, including some from archaeological specimens. This work provides a definitive framework for understanding the evolution and global spread of a notorious pathogen.

Leprosy’s niche

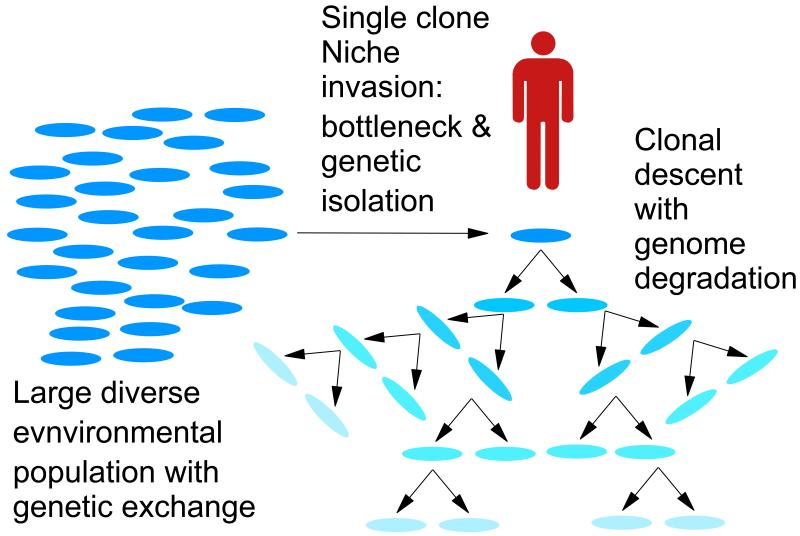

Other than humans, the nine-banded armadillo remains the only immunologically competent animal that can be reliably infected to develop disseminated leprosy3. The first genome sequence of M. leprae suggested that this extreme fastidiousness can be ascribed to loss of metabolic capacity, as a result of extensive gene decay4. These earlier genomic studies also indicated that M. leprae is derived from a single clone evolving asexually with no genetic exchange, properties shared with pathogens including Mycobacterium tuberculosis6,7, Yersinia pestis8, Bacillus anthracis9, and Salmonella enterica var Typhi10 and Treponema pallidum11. Although diverse in their origins and modes of transmission, these pathogens have all emerged recently in evolutionary terms by expansion into a new pathogenic niche but at the expense of participating in inter- and intra-specific genetic exchange. (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

The emergence of the single clone pathogen15. A single clone or small subset of a population of a free living bacterium (left) invades a new pathogenic niche, founding a population of low diversity. The pathogen becomes reproductively isolated from the ancestral population (right), while the pathogenic lifestyle precludes genetic exchange among members of the clone as it expands into its new niche. During expansion, the effects of purifying selection are reduced or eliminated by lack of competition with similar organisms, accompanied by genome degradation and a loss of fitness. Some adaptation to the host by positive selection may occur, but much of the reductive evolution is the accumulation of deleterious mutations. The accumulation mutation in different branches generates a fingerprint of mutations characteristic of each branch, enabling the phylogeny to be precisely reconstructed from whole genome sequence data.

The low levels of genetic exchange simplifies investigations of the evolution and epidemiology of such pathogens, as their population structures conform to the clonal paradigm. Their evolution is consequently accurately modelled by phylogenetic trees, the branches of which correspond to mutational events. The rarity of these events, however, presents the major challenge in the study of such bacteria as large amounts of sequence needs to be determined to identify relatively few informative characters12. For subtyping, therefore, either highly variable loci, such as variable nucleotide tandem repeats (VNTRs) or a subset of variable characters from multiple locations in the genome are typically chosen. These present difficulties of their own: VNTRs mutate and revert rapidly, obscuring patterns of descent, whereas a subset of SNPs is susceptible to phylogenetic discovery bias. This bias is introduced when two reference sequences are used to identify genetic variation that is assayed in a wider set of samples. As only the variation between the two reference sequences can be identified by these assays, many - and perhaps the most important - relationships among the wider sample set are lost, potentially giving highly misleading phylogenetic inferences13.

Typing schemes evolve

Monot et al.5 limited the problems of discovery bias by the genome sequencing of an additional strain (Br4923, from Brazil) as geographically diverse in origin from the originally sequenced strain (TN, from India) as possible. These strains were therefore unlikely to share a very recent common ancestor. The genome sequence of strain Br4923 was determined at 6× coverage, using parallel sequencing technologies and was very similar to the TN genome sequence, being only 141bp smaller. There were a total of 194 polymorphic sites, comprising 155 SNPs, 31 VNTRs and eight deletion and insertion events, between the two. For additional comparison, they sequenced two additional strains at high coverage using Illumina technology, from Thailand (Tha53 strain at 38× coverage) and the United States (NHDP63 strain at 46× coverage). These two strains also showed low genetic diversity, and from these the authors identified 201 SNPs, many shared with either the TN or Br4923 strains. For typing purposes they found the VNTR approach to be deficient and concentrated instead on a typing system based on informative mutations, identifying 78 informative SNPs from the genome sequences and surveying them in a set of 400 geographically diverse samples as well as some archaeological specimens. From these data they were able to classify strains into 16 SNP subtypes, which were clustered by geographical distribution and associated with patterns of human migration.

Single clone pathogens

The comparison of data from multiple M. leprae samples shows that they are all descendents of a single clone that underwent an extreme bottleneck and reductive evolution involving the inactivation of half of the genes in the chromosome4,14. It seems likely that at least some of the pseudogene formation predates the association of M. leprae with humans and an intermediate host, perhaps an invertebrate, may have been involved. The fact that all samples from humans are so similar (99.995% identical) shows that once in humans this single clone has spread extensively through populations, with some ongoing reductive evolution evidenced by the discovery of an additional five pseudogenes in the sequence of Br4932. The geographic and temporal pattern of the genetic variation observed in 400 contemporary samples, together with types determined from aDNA present in archaeological specimens as old as 1500 years, is consistent with human leprosy arising in humans in East Africa and spreading world wide with human migrations and trade. Interestingly, this ancient disease appears to have been introduced into the Americas by the slave trade rather than older human migrations.

Monot et al.5 shows the importance of whole genome analysis of sequence data for the accurate investigation of the epidemiology and evolution of M. leprae and other genetically monomorphic pathogens. With increasing accessibility of parallel sequencing technologies, we can anticipate epidemiological studies based on genome-wide variation of large numbers of microbiological specimens.13 The development here of a more robust means of typing M. leprae samples based on this genome-wide and phylogenetic analysis will facilitate epidemiological and evolutionary studies as we move towards global disease eradication2. Application of this typing scheme to contemporary and historical specimens provides the prospect of establishing a complete or near-complete history of this fascinating pathogen, even in those areas where the disease has long been eradicated.

References

- 1.Robbins G, et al. Ancient skeletal evidence for leprosy in India (2000 B.C.) PLoS One. 2009;4:e5669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anon . Report of the global forum on the elimination of leprosy as a public health problem. World Health Organisation; Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scollard DM, et al. The continuing challenges of leprosy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:338–81. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.338-381.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole ST, et al. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature. 2001;409:1007–11. doi: 10.1038/35059006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monot M, Honore N, Garnier T, et al. Comparative phylogeographic analysis of Mycobacterium leprae. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:1282–1289. doi: 10.1038/ng.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dos Vultos T, et al. Evolution and diversity of clonal bacteria: the paradigm of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wirth T, et al. Origin, spread and demography of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:e1000160. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Achtman M, et al. Microevolution and history of the plague bacillus, Yersinia pestis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2004;101:17837–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408026101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenefic LJ, et al. Pre-Columbian origins for North American anthrax. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roumagnac P, et al. Evolutionary history of Salmonella typhi. Science. 2006;314:1301–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1134933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper KN, et al. On the origin of the treponematoses: a phylogenetic approach. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Achtman M. Evolution, population structure, and phylogeography of genetically monomorphic bacterial pathogens. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2008;62:53–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pearson T, Okinaka RT, Foster JT, Keim P. Phylogenetic understanding of clonal populations in an era of whole genome sequencing. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:1010–9. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monot M, et al. On the origin of leprosy. Science. 2005;308:1040–2. doi: 10.1126/science/1109759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keim PS, Wagner DM. Humans and evolutionary and ecological forces shaped the phylogeography of recently emerged diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:813–21. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]