Abstract

Background & Aims

Little is known about the genetic factors that contribute to development of sessile serrated adenomas (SSAs). SSAs contain somatic mutations in BRAF or KRAS early in development. However, evidence from humans and mouse models indicates that these mutations result in oncogene-induced senescence (OIS) of intestinal crypt cells. Progression to serrated neoplasia requires cells to escape OIS, via inactivation of tumor suppressor pathways. We investigated whether individuals with multiple SSAs carry germline loss-of-function mutations (nonsense and splice-site) in genes that regulate OIS – the p16–Rb and ATM–ATR DNA damage response pathways.

Methods

Through bioinformatic analysis of the literature, we identified a set of genes that function at main nodes of the p16–Rb and ATM–ATR DNA damage response pathways. We performed whole-exome sequencing of 20 unrelated individuals with multiple SSAs; most had features of serrated polyposis. We compared sequences with those from 4300 individuals, matched for ethnicity (controls). We also used an integrative genomics approach to identify additional genes involved in senescence mechanisms.

Results

We identified mutations in genes that regulate senescence (ATM, PIF1, TELO2, XAF1, and RBL1) in 5/20 individuals with multiple SSAs (odds ratio [OR]=3.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.9–8.9; P=.04). In 2 individuals, we found nonsense mutations in RNF43, indicating that it is also associated with multiple serrated polyps (OR=460; 95% CI, 23.1– 16384; P=6.8×10−5). In knockdown experiments with pancreatic duct cells exposed to ultraviolet light, RNF43 appeared to function as a regulator of ATM–ATR DNA damage response.

Conclusions

We associated germline loss-of-function variants in genes that regulate senescence pathways with the development of multiple SSAs. We identified RNF43 as a regulator of the DNA damage response, and associated nonsense variants in this gene with high risk of developing SSAs.

Keywords: serrated polyposis syndrome, hereditary colon cancer, sessile serrated polyp, RNF43

Background and Aims

Sessile serrated adenomas (SSA) are a newly recognized precursor lesion to colorectal cancer. Found in 2% of average-risk individuals undergoing their first screening colonoscopy, SSAs are believed to give rise to sporadic microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) colon cancers, as well as BRAF-mutated microsatellite stable (MSS) colon cancers.1, 2 Despite their relative infrequency, serrated lesions are estimated to be responsible for approximately 20-35% of all colon cancers.3, 4 In contrast to tubular adenomas, SSAs are not dependent on mutations in the APC-beta catenin axis, but instead exhibit somatic mutations in BRAF, or less commonly KRAS, early in their development.4-6 To determine the presently unknown genetic susceptibility for this lesion, we chose to study individuals who develop multiple SSAs, a hallmark feature of serrated polyposis syndrome.

Although there is no clear consensus on the clinical definition of the serrated polyposis syndrome, its prevalence has been estimated to be as high as 1:3000 in populations primarily composed of European ancestry.7 Affected individuals possess as high as a 54% lifetime risk of colon cancer, and may display strong personal or family histories of extracolonic cancers.8, 9 Despite the broad phenotypic variability observed with this syndrome, epidemiological evidence demonstrates an underlying genetic risk. First degree relatives have a 32% risk of developing multiple serrated polyps, as well as a five-fold increased risk of colon cancer.10, 11 More recently, an increased risk of pancreatic cancer has also been observed.12 Attempts to model the genetics of this syndrome as monogenic among unrelated individuals, or as Mendelian through linkage analyses, have not been successful.13, 14 The genetic basis for this disorder remains undefined, with the exception that mutations in MUTYH have been observed in only a small minority of cases that present with concomitant tubular adenomas.15

Given this variable clinical presentation within an extreme phenotype and likely underlying genetic complexity and heterogeneity, we hypothesized that high-risk variants may be localized to specific pathways instead of a single gene. Whereas mice with inactivating mutations in APC rapidly develop tubular adenomas, BRAF or KRAS mutations that are associated with serrated polyps are alone insufficient to provoke intestinal tumorigenesis.16, 17 After a brief period of hyperproliferation, crypt cells undergo growth arrest due to metabolic and replicative stress, a process termed oncogene-induced senescence (OIS). Additional mutational events are required for neoplastic progression.18 Accordingly, engineered bypass of OIS at the genetic level quickly recapitulates the serrated neoplasia phenotype found in humans.17 In the human colon, OIS has been demonstrated to be primarily mediated by the p16-RB and ATM-ATR-mediated DNA damage response (DDR) pathways.19, 20 Since bypass of OIS is fundamental to SSA progression, we sought to determine whether individuals with multiple SSAs are enriched with germline, strong loss-of-function mutations (nonsense and splice-site) within either of these two pathways.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement and Study Recruitment

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) under Protocol #2011P001161. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Twenty unrelated study participants were recruited from clinics in the Gastroenterology Division of MGH.

Given our focus on SSAs specifically and not serrated polyps in general, we enrolled individuals diagnosed with multiple SSAs who fulfilled a set of criteria that were modified from the World Health Organization criteria for serrated polyposis in order to define a robust genotype-phenotype relationship for sessile serrated adenomas (Table 1).21 We exclusively counted SSAs regardless of size toward multiplicity thresholds despite the existence of other types of serrated polyps in study participants. Family history of serrated polyposis was expanded to include a family history of colorectal cancer given the strong associated genetic risk and the absence of SSAs from older pathology reports.22 Participants were excluded if they were previously diagnosed with a known polyposis syndrome through genetic testing. However, no individuals were excluded as a result of a positive genetic test.

Table 1.

Enrollment Criteria.

| Revised World Health Organization Criteria for Serrated Polyposis | Enrollment Criteria |

|---|---|

|

| |

|

|

Fulfillment of any of the three criteria is sufficient for diagnosis or enrollment. Polyp counts are intended to be cumulative over time. Example of other types of serrated polyps include traditional serrated adenomas and microvesicular type hyperplastic polyps.

Given that all study participants were of complete (95%) or partial (5%) European descent, we used the exomes of 4300 European-Americans from the NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project as genetic controls.23 No polyp or cancer histories are available for these individuals, and were assumed to be negative to bias the study toward the null hypothesis.

Gene Set Construction

Prospectively, we defined a gene set for the p16-Rb and ATM-ATR DDR pathways for which strong LoF mutations could impair OIS. Core components of the p16-Rb axis whose loss would result in impairment were previously defined as CDKN2A, CDKN2B, CDKN2C, CDKN2D, CDKN1A, CDKN1B, RB1, RBL1, and RBL2.24 Given the variable impact according to cell type of the numerous downstream effectors of the ATM-ATR-mediated DDR on OIS, we defined the critical nodes for this pathway as all genes whose loss results in diminished activation or function of DNA checkpoint kinases: ATM, ATR, Chk1, or Chk2. While p53 has been shown to be a critical downstream effector of senescence in other cell types, multiple animal studies have demonstrated that biallelic loss of p53 fails to increase intestinal polyp multiplicity, or accelerate progression of early stage conventional adenomas or serrated polyps. 17, 18, 25 As such, we did not incorporate p53 into our analysis.

A python script was devised to extract all 19,049 HGNC gene symbols of protein coding genes and all associated one-word gene synonyms from the ExPASy GPSDB Gene/Protein Synonyms finder (http://gpsdb.expasy.org/#). Subsequently, this script employed the e-utilities function of Pubmed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK25500/) to cross-reference each gene name and its synonyms sequentially against: “ATM”, “ATR”, “Chk1”, and “Chk2”. All search terms were coded as text words. This search algorithm yielded 313,747 Pubmed IDs last scanned as of December 11, 2012. Each title, abstract, and/or publication was manually reviewed. This analysis yielded 224 genes whose loss impaired activation or function of ATM, ATR, Chk1, or Chk2 (Supplementary Table 1). In addition to the 9 genes from the p16-RB pathway, the final gene set consisted of 233 genes for genes relevant to OIS pathways in the colon.

Genes containing cancer-related GWAS loci (P < 1.0 × 10−5) were obtained from the NHGRI Catalog of Genome-wide Association Studies (http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies/), which assigned loci to the closest gene if applicable. The search terms “cancer”,” tumor”, “leukemia”, “lymphoma”, “sarcoma”, “melanoma”, “myeloma”, “rhabdomyosarcoma”, and “schwannoma” were used to compile a list of 555 genes containing such loci (Supplementary Table 2).

Exome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood, or mouthwash samples if study participants harbored active hematopoietic neoplasms (Qiamp, Qiagen). Exome sequencing was performed by the Otogenetics Corporation (Norcross, GA). Illumina libraries were made from qualified fragmented genomic DNA (NEBNext reagents, New England Biolabs) and the resulting libraries were subjected to exome enrichment using NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library v2.0 (Roche NimbleGen, Inc.) or SureSelectXT Human All Exon v4 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) following the manufacturer's instructions. The samples were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform which generated paired-end reads of 100 nucleotides. Samples were sequenced to a mean depth greater than 50× (Supplementary Table 3).

The exome sequencing of 4300 individuals comprising the European-American cohort of ESP6500 was performed as previously described.23 Of note, sequencing was performed at a mean depth of ∼111x using both Agilent and Roche NimbleGen kits. Validation of a limited subset of single nucletotide variants (SNVs) previously revealed 98% accuracy for variants. For additional methods regarding variant processing, please see the Supplementary Methods.

Loss-Of-Function Variant Analyses

As performed in previous whole-exome studies of complex traits, we focused on loss-of-function single-nucleotide variants which are empirically defined as nonsense and essential splice-site mutations.26, 27 To exclude potentially indolent mutations from the analysis and call loss-of-function with high specificity, strong loss-of-functions mutations were prospectively defined as those LoF variants that affect all NCBI annotated isoforms for a given gene.28 In addition, since nonsense mutations toward the 3′ end may yield proteins with partial or full functionality, nonsense mutations were required to induce nonsense-mediated decay (occurring 50 base pairs before the last exon-exon junction).28, 29 For genes with only one coding exon, nonsense mutations had to truncate at least 50% of the protein. Variants of interest from study participants were validated through Sanger sequencing. Please see Supplementary Table 4 for PCR primers and conditions.

Somatic BRAF/KRAS Genotyping

Histology of SSAs were reviewed and confirmed (G.Y.L). SNaPshot genotyping assay was performed on DNA from one representative SSA from each enrolled patient, if not performed in the clinical setting. The assay consists of upfront multiplexed PCR followed by single-base extension reactions using the SNaPshot platform as previously reported.30 The following bases were genotyped: KRAS c.34G, c.35G, c.37G, c.38G, c.181C, c.182A, c.183A, and BRAF c.1397G, c.1406G, c.1789C, c.1798G, c.1799T.

Protein-Protein Interaction Network

The 86 genes of the predefined set found mutated among the controls were used as inputs into the Broad Institute's Disease Association Protein-Protein Link Evaluator (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/dapple/dapple.php).31 Fixed causal genes were listed as ATM, ATR, CHEK1, and CHEK2. Direct interactions were visualized and plotted.

Statistical Analysis

The cohort allelic sums test was employed to assess enrichment of strong LoF mutations of the gene set in cases compared to controls.32 A P < 0.05 was considered significant given that only one gene set was compared between cases and controls. To create an upperbound limit, each individual from the controls was assumed not to have more than one strong LoF mutation from the gene set. This assumption was necessary given that variant data provided for this cohort are genotype counts not localizable to any specific individuals. Any such variant in which the total number of controls assayed was short of 4300 individuals due to issues regarding coverage around a particular genomic region, the number of individuals affected was projected to 4300 based on the MAF. Among search of novel genes implicated by GWAS, a Bonferroni-corrected P < 9.0 × 10−5 was considered statistically significant given 555 individual gene comparisons made (Supplementary Table 2).

RNF43 Functional Studies

Creation of RNF43 stable knock-down pancreatic duct cells, DNA damage experiments, and western blot analyses are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods.

Results

Characteristics of Study Participants

We used a revised set of criteria based upon the World Health Organization criteria for serrated polyposis as a framework to define a robust genotype-phenotype relationship for sessile serrated adenomas (Table 1; see Materials and Methods).21 The clinical features of study participants are displayed in Table 2. Reaffirming the severe phenotypes selected, the median age at which study participants fulfilled enrollment criteria was considerably younger than the median age at which sporadic SSAs are found in the general population (52 vs. 61 years).33 The number of SSAs ranged from 3 to ≥ 50, representative of the broad range of polyp multiplicity that fulfills current criteria for serrated polyposis (≥ 1, ≥ 5, or ≥ 20). Sixteen out of the twenty participants met WHO clinical criteria. Three individuals had personal histories of colon cancer, eleven demonstrated family histories of colon cancer, and eight had one or more extracolonic neoplasms prior to their satisfying enrollment criteria (Table 2 and Supplemental Figure 1). After histological review of all polyps, genotyping of one representative SSA from each individual was performed in 19/20 study participants given sample availability. Eighteen of nineteen genotyped SSAs carried the BRAF V600E mutation, whereas the SSA of Study Participant #18 did not harbor an identifiable mutation in BRAF or KRAS.

Table 2. Characteristics of the Study Participants.

| Participant Number | Age | Gender | SSAs | Personal History of CRC (age) | 1° or 2° Relative with CRC (age) | Personal history of extracolonic malignancy (Age) | WHO Criteria (1,2,3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | Female | 23 | Yes (58) | No | Breast (45) Ovarian (55) | Yes (1&3) |

| 2 | 45 | Male | 6 | No | Father (56) | No | No |

| 3 | 44 | Male | 5 | No | No | No | Yes (1) |

| 4 | 38 | Female | 5 | No | Father (76) | No | Yes (1) |

| 5 | 50 | Male | 7 | No | No | Biliary (40) | Yes (1) |

| 6 | 51 | Female | >30 | No | Father (70s) | No | Yes (1&3) |

| 7 | 52 | Male | 9 | No | No | No | Yes (1) |

| 8 | 32 | Female | 7 | Yes (32) | Uncles (40s) | Schwannoma (32) | Yes (1) |

| 9 | 64 | Female | 10 | No | Sister (51) Maternal Grandmother (60) | No | Yes (1) |

| 10 | 52 | Male | > 50* | Synchronous (52) | No | Germ Cell (41) Bladder (49) | Yes (1&3) |

| 11 | 52 | Male | 10 | No | No | No | Yes (1) |

| 12 | 52 | Female | 7* | No | Maternal Uncle (70s) Maternal Aunt (70s) | No | Yes (1) |

| 13 | 53 | Male | 9 | No | No | No | Yes (1) |

| 14 | 51 | Male | 8 | No | Brother (58) Paternal Grandmother | Hodgkin's (34) Prostate (44) | Yes (1) |

| 15 | 40 | Female | 3 | No | Father (72) | No | No |

| 16 | 57 | Female | 33 | No | No | Hodgkin's | Yes (1,3) |

| 17 | 66 | Male | 8 | No | No | Melanoma (31) | Yes (1) |

| 18 | 55 | Female | 6 | No | Father (72) | No | No |

| 19 | 49 | Female | 7 | No | Maternal Uncle (45) Maternal Grandfather | No | No |

| 20 | 56 | Male | >25 | No | Maternal Uncle (72) | No | Yes (1&3) |

Age reported refers to the time at which the patient satisfied enrollment criteria. The polyp counts are current as of the time of submission.

Designates individuals who underwent partial or total colectomy.

Loss-of-Function Mutations within Pathways of Oncogene-Induced Senescence

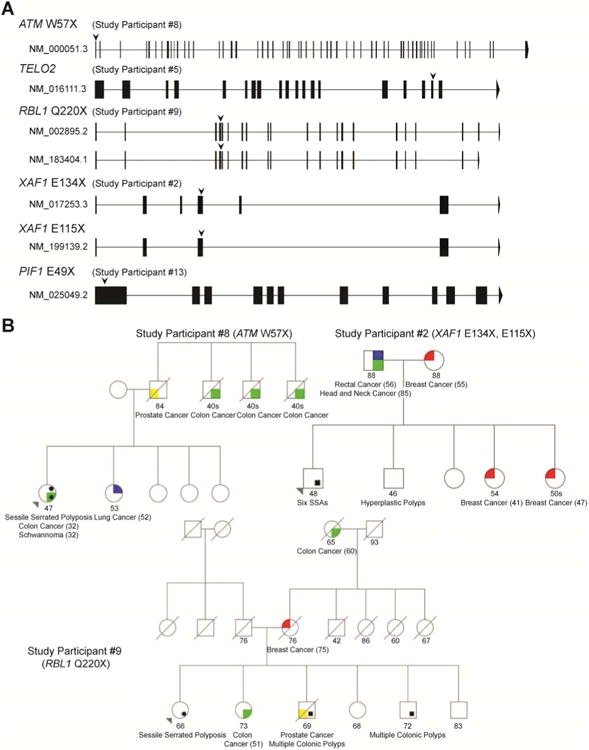

We used computational approaches to define a set of central regulators of OIS and compared the prevalence of strong LoF mutations between cases and controls (Materials and Methods). Consistent with prior genetic studies of serrated polyposis, no single gene was found to be mutated in multiple participants. However, we detected strong LoF mutations in five different genes (ATM, TELO2, RBL1, XAF1, and PIF1) within our predefined gene set in five individuals (Figure 1a). All variants were verified by Sanger sequencing (Supplemental Figure 2). Study participant #8, with a previously undescribed nonsense mutation in ATM, demonstrated a strong personal and family history of colorectal and extracolonic cancers (Figure 1b). While somatic nonsense mutations in ATM occur frequently in colon cancer, germline mutations have thus far been implicated in hereditary breast and pancreatic cancers.34-36 Study participant #5 possessed a 5′ essential splice-site mutation in TELO2 and a personal history of early-onset cholangiocarcinoma. TELO2 encodes for the protein Tel2, which facilitates the stability and activation of ATM and ATR through direct physical binding; loss of Tel2 expression inhibits Chk1/Chk2 activation in the setting of DNA damage.37 Study participants #2 and #9 each possessing a first-degree relative with CRC, carried nonsense mutations in RBL1 and XAF1 (rs146752602), respectively (Figure 1b). Loss of RBL1, which encodes the p107 protein that is a key constituent of the p16-Rb pathway, facilitates the development of dysplasia in the intestinal epithelium, as well as Ras-mediated transformation.38, 39 XAF1, a binding partner and activator of Chk1, shows decreased expression in 40% of colon cancers, and loss of heterozygosity noted in 36%.40, 41 Decreased expression of XAF1 has been also noted in esophageal and pancreatic cancers.42, 43 Study participant #13 harbored a nonsense mutation in PIF1, a DNA helicase which maintains genomic stability by facilitating Chk1 activation and negatively suppressing telomerase.44, 45

Figure 1. Strong Loss-of-Function Mutations Among Study Participants.

(A) Gene structure diagrams for all official isoforms of mutated genes. Vertical structures along the line demonstrate exons. Downward pointing arrows indicate the site of mutations. Isoforms are labeled with RefSeq IDs. (B) Pedigrees of study participants with identifiable mutations in the gene set and family histories of colon cancer. Ages are current as of time of publication. Study participants #5 and #13 did not have family histories of colon or extracolonic cancers and are not displayed.

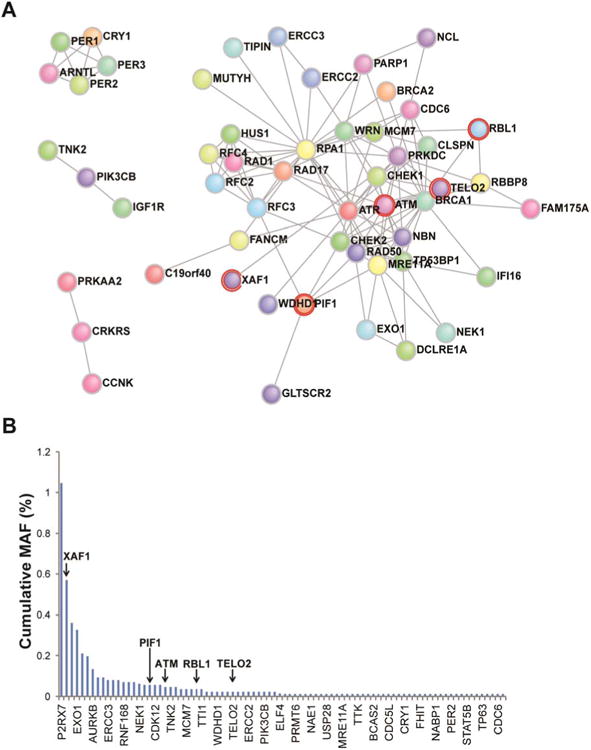

Among controls, strong LoF mutations were found in 86/233 genes of the predefined set, and their network topology demonstrated extensive, direct protein-protein interactions (Figure 2a). Compatible with strong purifying selection, cumulative minor allele frequencies (MAF) of strong LoF mutations for each gene rarely exceeded 0.1%, and did not surpass 1.1% (Figure 2b and Supplementary Table 5). Overall, 25% of study participants harbored at least one strong LoF mutation in the gene set compared to 9.87% of controls (5/20 vs. 424/4300, odds ratio [OR]=3.0; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.9–8.9; P=.04, Fisher's two-tailed exact test).

Figure 2. Strong Loss-of-Function Mutations Among Controls.

(A) Direct protein-protein interaction network of gene set mutations discovered in controls. Red halos designate genes also found mutated in cases. (B) Cumulative MAFs of each mutated gene in order of decreasing frequency. Arrows designate genes found in cases. The skewness was 8.8 and kurtosis was 92.1.

Loss-of-Function Analysis Facilitates Discovery of RNF43 as a High-Risk Variant for the Development of Multiple Serrated Polyps

From this significant enrichment, we next hypothesized that the remaining fifteen study participants possessed strong LoF mutations in genes not yet implicated in the regulation of OIS. Each study participant harbored approximately 5 rare, strong LoF mutations from the exome (Supplementary Table 6). To demonstrate the utility of LoF analysis for gene discovery, we searched for strong LoF mutations within genes containing loci implicated by genome-wide associated studies (GWAS) of all cancers. We searched among GWAS of all cancers instead of just colon cancer specific studies given that mechanisms of senescence are broadly applicable to all cancers. Of note, minimal overlap exists between our predefined gene set of OIS and the set of all genes with loci identified from GWAS of cancers, demonstrating that only a small fraction of genes containing GWAS loci (1.8%) have previously been linked to mechanisms of senescence (Supplementary Figure 3).

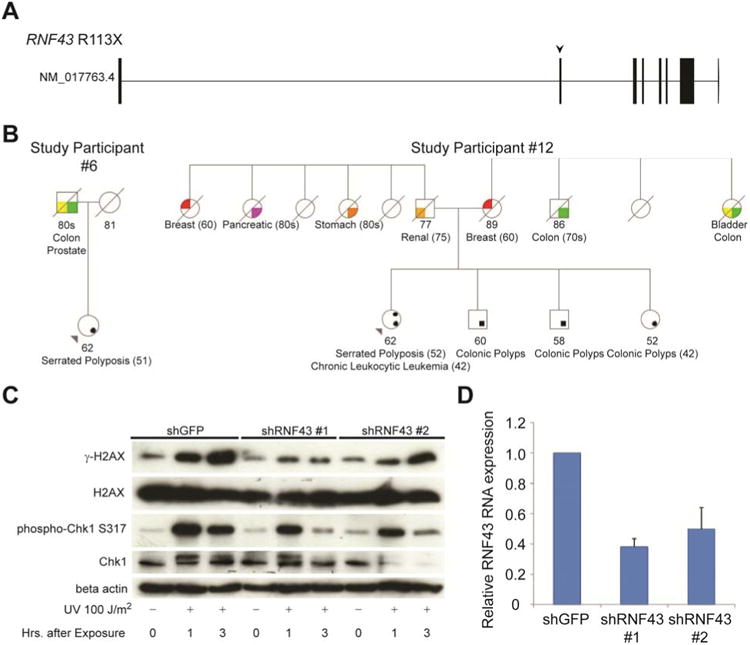

Two genes that contain GWAS loci were discovered with strong LoF mutations among the fifteen remaining study participants. Study participants #4 and #11 possessed the rare variant (rs199884004), ULK4 R862X (2/20 vs. 45/4300; 10% vs. 1%; OR=10.5; 95% CI, 1.1-45.8, P=0.02). A missense variant in ULK4 has already been associated with multiple myeloma.46 While its function is unknown, expression of its paralog, ULK3, has been observed to be increased in Ras-induced senescence, and its overexpression also induces a senescence phenotype.47 Study participants #6 and #12 harbored the identical, novel germline mutation, RNF43 R113X (Figure 3a and 3b) and had family histories of colon cancer. This enrichment of strong LoF mutations in RNF43 in our cohort reached statistical significance (2/20 vs. 1/4300; 10% vs. 0.02%; OR=460; 95% CI, 23.1 – 16384; P=6.8x10–5). RNF43 has been implicated in a GWAS of pancreatic cancer among Japanese, and has been reported as among the most frequently mutated genes in cystic tumors of the pancreas.48, 49 More recently, knockout of RNF43 has been demonstrated to contribute toward an intestinal polyposis phenotype in mice.50

Figure 3. RNF43 Modulates the ATM-ATR-mediated DNA Damage Response Pathway.

(A) Gene-structure diagram of the germline RNF43 mutation identified from the study participants. Arrow demonstrates site of nonsense mutation. (B) Pedigrees of study participants with germline RNF43 mutations. (C) Western blots of protein isolated from KRAS mutated pancreatic duct cells. Cells were stably transfected with short hairpin constructs targeting either GFP or RNF43, and exposed to UV irradiation as indicated. (D) Efficacy of RNF43 silencing in stably transfected pancreatic duct cells. Error bars designate standard error of the mean.

RNF43 expression has been shown to be increased in tubular adenomas and conventional adenocarcinomas, so we next examined the expression profiles of RNF43 in SSAs and cancers arising from the serrated pathway to confirm a possible tumor suppressor role in this setting. As a direct transcriptional target of Wnt signaling, RNF43 has been demonstrated to have a homeostatic role and tumor suppressive role by inducing endocytosis of Wnt receptors.51 Analyzing several published microarray datasets (see Supplemental Methods), we observed that in contrast to tubular adenomas, SSAs demonstrated no significant increase in RNF43 expression when compared to normal mucosa (Supplementary Figure 4). In addition, a direct comparison of RNF43 expression between SSAs and tubular adenomas demonstrated a statistically significant, 2.2-fold decrease in SSAs. Moreover, this ratio was sustained in independent microarray studies when comparing expression profiles of adenocarcinomas derived from the serrated pathway versus conventional adenocarcinomas. These findings demonstrate a relative reduction of RNF43 expression in the serrated pathway compared to the conventional pathway of colon carcinogenesis.

RNF43 is a Novel Regulator of the ATM-ATR-mediated DNA Damage Response Pathway

The strong statistical signal from our case-control analysis and prior observations linking RNF43 to UV-induced apoptosis prompted us to investigate the potential interplay between RNF43 and the DDR pathway in the context of precancerous lesions.52 We chose pancreatic duct cells expressing activated KrasG12D from the endogenous promoter (generated from Pdx1-Cre; LSL-KRASG12D mice; Supplemental Methods) as a tractable in vitro model system. These cells have intact OIS checkpoint genes and provide a relevant experimental context to study the genetic interactions between KRAS and RNF43 mutations, as these lesions are observed concurrently in a significant subset of pancreatic cystic tumors.

We generated matched lines with RNF43 knockdown or control shRNA, and examined response to UV irradiation. RNF43 depleted cells exhibited sharply diminished accumulation of γ-H2Ax and phosphorylated Chk1 compared to control cells within the first several hours of UV exposure (Figure 4c). This effect was also seen at variable doses of UV radiation (Supplementary Figure 5). RNF43 knockdown and control cells exhibited comparable proliferation rates, indicating that the diminished levels of γ-H2Ax and phosphorylated Chk1 were not a consequence of cell cycle arrest from RNF43 knockdown (Supplementary Figure 6). Thus, impairment of RNF43 function in precancerous cells results in the dampening of the DDR pathway.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that an excess of rare, strong LoF mutations (nonsense and splice-site) in genes that regulate primary mechanisms of OIS in the colon are associated with the development of multiple SSAs. To discover this association, we focused our analysis on rare variants. Recently, much of the genetic research in colon cancer has focused on the search for common variants. However, multiple GWAS and subsequent meta-analyses have not revealed genetic factors that can acccount for the overall heritability for colon cancer. Increasing evidence is emerging that a large fraction of this missing heritability for complex diseases may instead arise from a heterogeneous collection of rare variants.53, 54 Large scale exome sequencing projects have revealed that the bulk of protein-coding variation in populations is rare and has occurred recently, arising from rapid population growth outpacing selection pressures over the past 5,000 to 10,000 years.55 Extreme phenotype design of whole-exome studies has facilitated the identification of rare variants in complex diseases.56

To understand the genetic susceptibility to SSA development, we studied individuals who developed multiple SSAs, many of whom met criteria for serrated polyposis. We hypothesized that such individuals should be enriched with severe mutations. However, given the low prevalence of serrated polyposis syndrome in the general population, the genetic heterogeneity of the disorder, and the high false-positive rate of missense variant prediction algorithms, obtaining sufficient statistical power for testing of individual rare or private variants is not feasible or practical.57 To overcome this limitation, we leveraged observations regarding disease pathogenesis from prior animal and human studies and restricted our focus to disease-implicated pathways instead of individual genes to gain additional statistical power. We further restricted our analysis to empirically defined loss-of-function variants (nonsense and splice-site), which has been demonstrated to be a useful tool in exome-sequencing studies to implicate genes and pathways associated with complex traits.27

This hypothesis-driven approach focusing on molecular pathways revealed that germline alterations in OIS pathways are associated with the formation of multiple SSAs. Of note, three of the initial five genes with strong LoF variants that were identified (ATM, RBL1, and XAF1) have been already established as genes implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis through human or animal studies. To reinforce the importance of these senescence mechanisms in disease pathogenesis, we subsequently demonstrated that remaining study participants harbored rare or novel LoF mutations in genes not yet implicated in these pathways. Through an integrative genomics approach, we identified RNF43 as another high-risk gene for the development of multiple serrated polyps that may also regulate senescence through the DDR. Including RNF43, we identified strong LoF mutations in 35% of study participants.

These results have important implications for clinical practice. In contrast to established polyposis syndromes such as Familial Adenomatous Polyposis or MUTYH-Associated Polyposis, single gene tests are unlikely to capture the wide genetic heterogeneity associated with the development of multiple serrated polyps. Clinical whole-exome sequencing may be required to identify high-risk variants in patients. While identification of these rare variants in affected individuals may permit personalized approaches to identify at-risk relatives, counseling about the unique risks of each of these genes may be difficult given the numerous genes involved and their varying effect sizes. Also, any identified pathogenic mutation may not be described in large cohorts of controls or cases, preventing precise quantification of risk. As a result, as clinicians obtain more personalized genomic information, they may be required to infer recommendations from qualitative basic science and translational studies to guide their clinical management.

An additional challenge is that many of these rare variants may or already have significant pleiotropic effects on the risk of developing other extra-colonic cancers. In our cohort, a large fraction of study participants demonstrated strong personal or family histories of early-onset extra-colonic cancers (Supplementary Figure 1). Among the genes discovered in our cohort, ATM mutations have been already described in the development of hereditary breast and pancreatic cancers. RNF43 is among the most frequently mutated genes in cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. While additional studies are required to formally quantify the risk of these pathways in the development of colon and extra-colonic cancers in family members, it is important to note that oncogene-induced senescence is relevant not only to SSAs but also to the development of most neoplasia. Thus far, pancreatic cancer has been linked to serrated polyposis in one cohort.12 However, tissue specificity and penetrance of these cancers may be secondary to environmental exposures and epistatic relationships among other variants in the genome.

There are several limitations to our study. The first derives from the existing WHO criteria for serrated polyposis, which we used as a framework. These clinical criteria encompass a broad phenotype, incorporating different polyp multiplicities, polyp location, polyp size, and family history (Table 1). To maximize discovery of genetic contributors, we developed modified criteria. We omitted polyp size, as it is dependent on timing of endoscopy and often an estimate by the endoscopist. In addition, serrated polyps are now more likely to be removed at sizes smaller than 1 cm due to their increased recognition. We used family history of CRC as a substitute for family history of serrated polyposis given the established risk among first-degree relatives and failure to recognize SSAs in older pathology reports. Another limitation of this study is that polyp or cancer histories of controls were not available and assumed to be negative. As a consequence, though, our calculated association of multiple SSAs with these LoF variants is likely an underestimate.

Our study is the first exome-wide genetic analysis of individuals who develop multiple SSAs, many of whom satisfy criteria for serrated polyposis syndrome. Utilizing a hypothesis-driven approach to exome sequencing, we demonstrate that such individuals harbor LoF mutations in established and novel regulators of OIS. In addition to laying the foundation for further refinement of genotype-phenotype relationships in SSA development, these findings provide a framework for studying the genetics of the broader set of malignancies occurring in these individuals and their families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to Andrew J. Mills for his programming and debugging assistance, and Julie Nagle for assistance in virus preparation and quantitative RT-PCR. We thank Kristen Shannon, Andrew Chan, Andrew DeLemos, Peter Kelsey, Norm Nishioka, and Barbara Nath for study recruitment and pedigrees, and Ramnik Xavier for his helpful discussions.

Grant Support: Supported by the grants of American College of Gastroenterology (Pilot Clinical Research Award, M.K.G), Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan (22590754, Y.M.), Warshaw Institute for Pancreatic Cancer Research (Y.M.), National Institutes of Health (CA92594, D.C.C.), and the Kate J. and Dorothy L. Clapp Fund (D.C.C.).

Abbreviations

- DDR

DNA Damage Response

- ESP6500

Exome Sequencing Project 6500 Cohort

- GWAS

genome-wide associated studies

- GATK

Genome Analysis Toolkit

- HGNC

HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

- NHLBI

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- OIS

oncogene-induced senescence

- SNV

single nucleotide variant

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SSA

sessile serrated adenoma

Footnotes

Disclosures: No conflicts of interests reported

Author Contributions.: M.K.G. and D.C.C conceived and designed the study. M.K.G., Y.M., K.M., T.A., M.Y. performed the functional experiments. M.K.G. and L.P.L. performed tumor genotyping. G.Y.L. performed pathological review. M.K.G. performed all bioinformatics analyses. N.B and D.C.C. supervised the project. M.K.G., N.B., and D.C.C. wrote the manuscript.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Buda A, De Bona M, Dotti I, et al. Prevalence of different subtypes of serrated polyps and risk of synchronous advanced colorectal neoplasia in average-risk population undergoing first-time colonoscopy. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2012;3:e6. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patil DT, Shadrach BL, Rybicki LA, et al. Proximal colon cancers and the serrated pathway: a systematic analysis of precursor histology and BRAF mutation status. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1423–31. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2088–100. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snover DC. Update on the serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2011;42:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu X, Li L, Peng Y. Wnt signalling pathway in the serrated neoplastic pathway of the colorectum: possible roles and epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:675–9. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien MJ, Yang S, Mack C, et al. Comparison of microsatellite instability, CpG island methylation phenotype, BRAF and KRAS status in serrated polyps and traditional adenomas indicates separate pathways to distinct colorectal carcinoma end points. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1491–501. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213313.36306.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosty C, Parry S, Young JP. Serrated polyposis: an enigmatic model of colorectal cancer predisposition. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:157073. doi: 10.4061/2011/157073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyman NH, Anderson P, Blasyk H. Hyperplastic polyposis and the risk of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:2101–4. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vandrovcova J, Lagerstedt-Robinsson K, Pahlman L, et al. Somatic BRAF-V600E mutations in familial colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2270–3. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oquinena S, Guerra A, Pueyo A, et al. Serrated polyposis: prospective study of first-degree relatives. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283598506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boparai KS, Reitsma JB, Lemmens V, et al. Increased colorectal cancer risk in first-degree relatives of patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome. Gut. 2010;59:1222–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.200741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Win AK, Walters RJ, Buchanan DD, et al. Cancer risks for relatives of patients with serrated polyposis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:770–8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chow E, Lipton L, Lynch E, et al. Hyperplastic polyposis syndrome: phenotypic presentations and the role of MBD4 and MYH. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:30–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts A, Nancarrow D, Clendenning M, et al. Linkage to chromosome 2q32.2-q33.3 in familial serrated neoplasia (Jass syndrome) Fam Cancer. 2011;10:245–54. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9408-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boparai KS, Dekker E, Van Eeden S, et al. Hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas as a phenotypic expression of MYH-associated polyposis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:2014–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carragher LA, Snell KR, Giblett SM, et al. V600EBraf induces gastrointestinal crypt senescence and promotes tumour progression through enhanced CpG methylation of p16INK4a. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:458–71. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennecke M, Kriegl L, Bajbouj M, et al. Ink4a/Arf and oncogene-induced senescence prevent tumor progression during alternative colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:135–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rad R, Cadinanos J, Rad L, et al. A Genetic Progression Model of Braf(V600E)-Induced Intestinal Tumorigenesis Reveals Targets for Therapeutic Intervention. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartkova J, Rezaei N, Liontos M, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature. 2006;444:633–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kriegl L, Neumann J, Vieth M, et al. Up and downregulation of p16(Ink4a) expression in BRAF-mutated polyps/adenomas indicates a senescence barrier in the serrated route to colon cancer. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1015–22. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snover DAD, Burt R, Odze RD. Serrated Polyps of the Colon and Rectum and Serrated Polyposis. In: Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang JJ, Alrawi S, Tan D. Nomenclature, molecular genetics and clinical significance of the precursor lesions in the serrated polyp pathway of colorectal carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2008;1:317–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tennessen JA, Bigham AW, O'Connor TD, et al. Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science. 2012;337:64–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1219240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiedemeyer WR, Dunn IF, Quayle SN, et al. Pattern of retinoblastoma pathway inactivation dictates response to CDK4/6 inhibition in GBM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11501–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001613107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fazeli A, Steen RG, Dickinson SL, et al. Effects of p53 mutations on apoptosis in mouse intestinal and human colonic adenomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10199–204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacArthur DG, Tyler-Smith C. Loss-of-function variants in the genomes of healthy humans. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:R125–30. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanders SJ, Murtha MT, Gupta AR, et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012;485:237–41. doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balasubramanian S, Habegger L, Frankish A, et al. Gene inactivation and its implications for annotation in the era of personal genomics. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1–10. doi: 10.1101/gad.1968411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacArthur DG, Balasubramanian S, Frankish A, et al. A systematic survey of loss-of-function variants in human protein-coding genes. Science. 2012;335:823–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1215040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dias-Santagata D, Akhavanfard S, David SS, et al. Rapid targeted mutational analysis of human tumours: a clinical platform to guide personalized cancer medicine. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:146–58. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossin EJ, Lage K, Raychaudhuri S, et al. Proteins encoded in genomic regions associated with immune-mediated disease physically interact and suggest underlying biology. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgenthaler S, Thilly WG. A strategy to discover genes that carry multi-allelic or monoallelic risk for common diseases: a cohort allelic sums test (CAST) Mutat Res. 2007;615:28–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lash RH, Genta RM, Schuler CM. Sessile serrated adenomas: prevalence of dysplasia and carcinoma in 2139 patients. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:681–6. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.075507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldgar DE, Healey S, Dowty JG, et al. Rare variants in the ATM gene and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R73. doi: 10.1186/bcr2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts NJ, Jiao Y, Yu J, et al. ATM mutations in patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:41–6. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takai H, Wang RC, Takai KK, et al. Tel2 regulates the stability of PI3K-related protein kinases. Cell. 2007;131:1248–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haigis K, Sage J, Glickman J, et al. The related retinoblastoma (pRb) and p130 proteins cooperate to regulate homeostasis in the intestinal epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:638–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams JP, Stewart T, Li B, et al. The retinoblastoma protein is required for Rasinduced oncogenic transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1170–82. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.4.1170-1182.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, Gu Q, Li M, et al. Identification of XAF1 as a novel cell cycle regulator through modulating G(2)/M checkpoint and interaction with checkpoint kinase 1 in gastrointestinal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1507–16. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung SK, Lee MG, Ryu BK, et al. Frequent alteration of XAF1 in human colorectal cancers: implication for tumor cell resistance to apoptotic stresses. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2459–77. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen XY, He QY, Guo MZ. XAF1 is frequently methylated in human esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2844–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i22.2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang J, Yao WY, Zhu Q, et al. XAF1 as a prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:559–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gagou ME, Ganesh A, Thompson R, et al. Suppression of apoptosis by PIF1 helicase in human tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4998–5008. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paeschke K, Bochman ML, Garcia PD, et al. Pif1 family helicases suppress genome instability at G-quadruplex motifs. Nature. 2013;497:458–62. doi: 10.1038/nature12149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Broderick P, Chubb D, Johnson DC, et al. Common variation at 3p22.1 and 7p15.3 influences multiple myeloma risk. Nat Genet. 2012;44:58–61. doi: 10.1038/ng.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young AR, Narita M, Ferreira M, et al. Autophagy mediates the mitotic senescence transition. Genes Dev. 2009;23:798–803. doi: 10.1101/gad.519709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Low SK, Kuchiba A, Zembutsu H, et al. Genome-wide association study of pancreatic cancer in Japanese population. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu J, Jiao Y, Dal Molin M, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of neoplastic cysts of the pancreas reveals recurrent mutations in components of ubiquitin-dependent pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:21188–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118046108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koo BK, Spit M, Jordens I, et al. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature. 2012;488:665–9. doi: 10.1038/nature11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hao HX, Xie Y, Zhang Y, et al. ZNRF3 promotes Wnt receptor turnover in an R-spondin-sensitive manner. Nature. 2012;485:195–200. doi: 10.1038/nature11019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shinada K, Tsukiyama T, Sho T, et al. RNF43 interacts with NEDL1 and regulates p53-mediated transcription. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;404:143–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bodmer W, Bonilla C. Common and rare variants in multifactorial susceptibility to common diseases. Nat Genet. 2008;40:695–701. doi: 10.1038/ng.f.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keinan A, Clark AG. Recent explosive human population growth has resulted in an excess of rare genetic variants. Science. 2012;336:740–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1217283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fu W, O'Connor TD, Jun G, et al. Analysis of 6,515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein-coding variants. Nature. 2013;493:216–20. doi: 10.1038/nature11690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Emond MJ, Louie T, Emerson J, et al. Exome sequencing of extreme phenotypes identifies DCTN4 as a modifier of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:886–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiezun A, Garimella K, Do R, et al. Exome sequencing and the genetic basis of complex traits. Nat Genet. 2012;44:623–30. doi: 10.1038/ng.2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.