Abstract

Following gene transfer of adeno-associated virus 2/8 (AAV2/8) to the muscle, C57BL/6 mice show long-term expression of a nuclear-targeted LacZ (nLacZ) transgene with minimal immune activation. Here, we show that pre-exposure to AAV2/8 can also induce tolerance to the more immunogenic AAV2/rh32.33 vector, preventing otherwise robust T-cell activation and allowing stable transgene expression. Depletion and adoptive transfer studies showed that a suppressive factor was not sufficient to account for AAV2/8-induced tolerance, whereas further characterization of the T-cell population showed upregulation of the exhaustion markers PD1, 2B4, and LAG3. Furthermore, systemic administration of Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands at the time of AAV2/rh32.33-administration broke AAV2/8-induced tolerance, restoring T-cell activation and β-gal clearance. As such, AAV2/8 transduction appears to lack the inflammatory signals necessary to prime a functional cytotoxic T-cell response. Inadequate T-cell priming could be explained upstream by AAV2/8's poor transduction and activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Immunohistochemical analysis indicates that AAV2/8 transduction also fails to upregulate major histocompatibility complex class I (MHCI) expression on the surface of myocytes, rendering transduced cells poor targets for T-cell–mediated destruction. Overall, AAV2/8-induced tolerance in the muscle is multifactorial, spanning from poor APC transduction and activation to the subsequent priming of functionally exhausted T-cells, while simultaneously avoiding upregulation of MHCI on potential targets.

Introduction

In many preclinical models, adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene transfer leads to stable, long-term gene expression in the absence of immunological sequelae. However, the conflicting experience in higher order animals and human clinical trials has forced the field to reassess the immunogenicity of these vectors.1 We have previously shown that even within small animal models, the structure of the AAV capsid has the potential to differentially impact the generation of cellular immunity, not only by dictating capsid antigenicity but also by augmenting T cell responses toward vector-encoded transgene products, referred to hereafter as the transgene-specific T cell response.2 Certain, more immunogenic capsid variants, such as AAVrh32.33, are able to prime qualitatively and quantitatively robust transgene-specific CD8+ T cell responses capable of clearing transduced cells in mice, and more closely mimicking the immune response often generated to AAV vectors in higher order species. Mechanistically, we found that the AAVrh32.33 capsid augments the CD8+ T cell response by generating more CD40L-dependent CD4+ T cell help. These studies emphasize the importance of modeling immune activation or tolerance in small animals in order to study the mechanisms of immunogenicity, which may translate to increased safety in future clinical applications.

In contrast to the robust immunogenicity of AAVrh32.33 in murine models, numerous other serotypes and capsid variants fail to activate T cells in vivo, even to highly antigenic, nonself transgenes, resulting in the long-term stability of transduced cells in numerous different tissues.2,3,4,5,6,7 The ability of AAV vectors to avoid immune activation in mice is the subject of continued investigation, though a variety of mechanisms have already been proposed. Initial studies from our lab suggested that AAV2 poorly transduces antigen-presenting cells (APCs), diminishing T cell priming and leading to a state of immunologic ignorance.8 Others have indicated that antigen-specific T cells were indeed formed, however, in the absence of inflammation or costimulation, they were nonfunctional or anergic.9 Most recently, studies of liver-directed gene transfer have shown that a population of regulatory T cells (Tregs) can lead to suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses.10,11 Our most recent findings have shown that Tregs work in concert with liver macrophages to induce hepatic tolerance, and that poor upregulation of peptide display machinery on the surface of transduced target cells can also contribute to the avoidance of CTL-mediated clearance.12,13

In addition to the effects of host species and capsid serotype, numerous other factors can also impact mechanisms of tolerance induction to AAV vectors, including route of administration, promoter specificity, and the levels of pre-existing inflammation in the target tissue. As the liver has proven to be a more tolerogenic organ than muscle, the majority of studies addressing mechanisms of AAV-induced tolerance have focused on hepatic gene transfer. Here, we investigate the mechanisms of tolerance induction to AAV8 in the muscle. We propose that, in this setting, AAV8 induces tolerance through a myriad of factors, spanning from poor APC transduction and activation, to the subsequent priming of functionally exhausted T cells, while simultaneously avoiding upregulation of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHCI) on potential targets. Previous reports in the literature support this hypothesis by documenting the upregulation of PD1 and 2B4 (CD244), markers of T cell exhaustion, in response to AAV2/7,14 and by confirming the importance of early inflammatory signals in rendering transduced hepatocytes sensitive to the effector activities of CTLs.13 Ultimately, our studies provide critical insight into the mechanisms of transgene-specific tolerance induction following AAV vector-mediated gene delivery to the muscle.

Results

AAV8 elicits weak T cell activation in the muscle of C57BL/6 mice

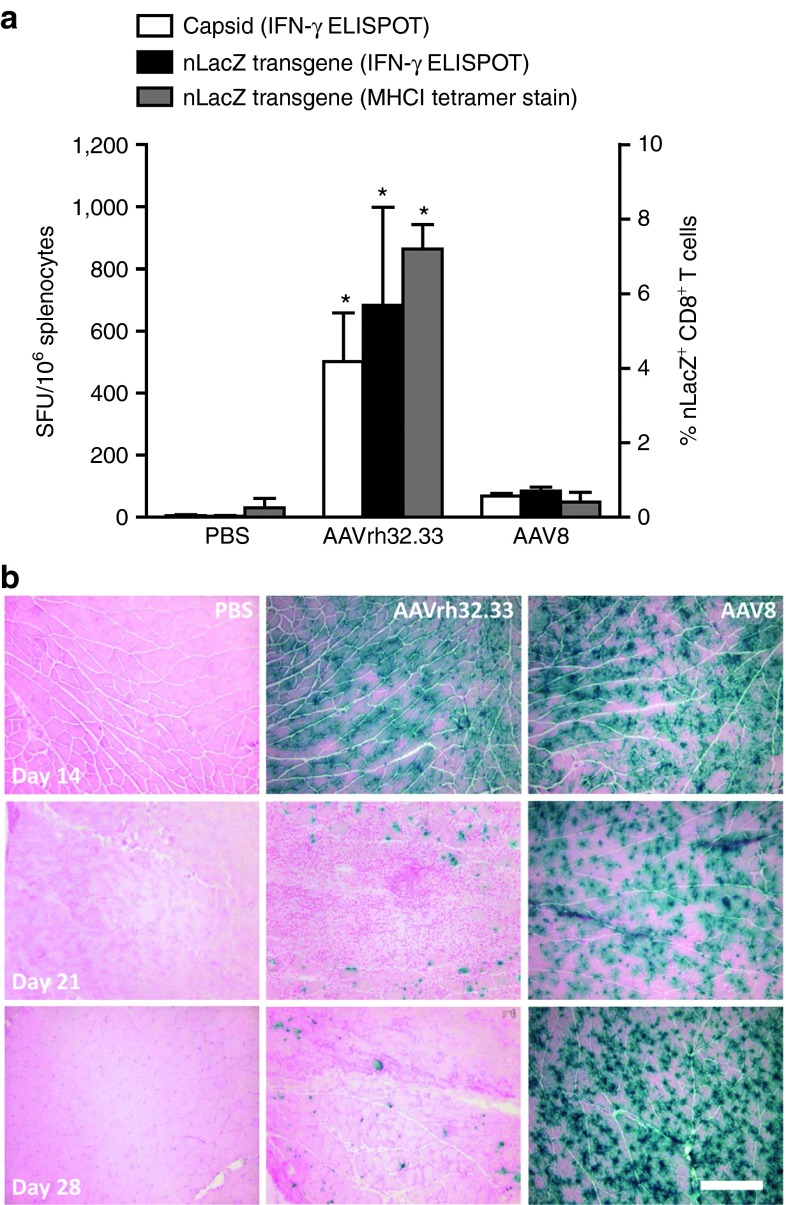

As we have previously reported, the structure of the AAV capsid differentially impacts the generation of cellular immunity to both capsid and transgene antigens.2 Here, we first confirmed that AAV8 generates minimal T cell activation in the muscle of C57BL/6 mice when compared with the more immunogenic capsid variant, AAVrh32.33 (Figure 1). Briefly, 1011 genome copies (GC) of either AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 vectors expressing a nuclear-targeted LacZ (nLacZ) transgene were injected into the muscle of C57BL/6 mice. Mice were sacrificed at days 14, 21, and 28 for histochemical analysis to determine transduction efficiency and stability of β-gal expression. At the peak of the T cell response, lymphocytes were isolated from the spleen for interferon-γ (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT), and MHCI tetramer staining was performed on whole blood. While AAV2/rh32.33 generated a robust T cell response to both capsid and transgene antigens at day 21, AAV2/8 showed minimal T cell activation when compared with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-injected controls (Figure 1a). While both vectors showed a similar onset of β-gal expression in muscle sections at day 14, by day 21, the number of β-gal positive fibers in AAV2/rh32.33-injected mice was substantially reduced, concomitant with the onset of severe cellular infiltration (Figure 1b). The reduction in β-gal expression continued through day 28, with complete clearance observed by day 63 (Figure 1b and data not shown). In contrast, AAV2/8-injected mice showed minimal cellular infiltration and levels of β-gal expression that were consistent and stable through day 28 (Figure 1b). The stability of β-gal expression in AAV2/8.nLacZ-injected mice has been followed through day 105 (data not shown). The quality of the cellular infiltrate was analyzed in further detail by confocal staining in a previous report.2

Figure 1.

AAV2/8 induces poor T cell activation and stable transgene expression in vivo. (a) C57BL/6 mice were injected intramuscularly with 1011 genome copies of AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing CB.nLacZ. At day 21, whole blood was acquired for nLacZ-specific MHCI tetramer staining (right axis, gray bars), and mice were necropsied to harvest spleen for IFN-γ ELISPOT (left axis) and (b) muscle for X-gal histochemistry at day 28. (a) Splenocytes (left axis) were stimulated with the dominant H-2Kb CD8+ T cell epitopes for either the AAV8 or AAVrh32.33 capsid (white bars) or the β-gal transgene (black bars). PBS-injected mice showed no activation in response to the AAV8 or AAVrh32.33 capsid epitopes (stimulation against AAV8 capsid epitope is shown). AAVrh32.33-injected mice showed no activation in response to the AAV8 capsid; AAV8-injected mice showed no activation in response to the AAVrh32.33 capsid epitope (data not shown). Data represent a mean ± SD for four mice per group, where *P ≤ 0.05 compared with PBS or AAV2/8. Results were confirmed by three independent experiments. (b) Representative images from four mice per group are shown here under 10× magnification; scale bar represents 200 µm. AAV, adeno-associated virus; ELISPOT, enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot; IFN-γ, interferon-γ MHCI, major histocompatibility complex class I; nLacZ, nuclear-targeted LacZ; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Previous exposure to AAV8 induces transgene-specific tolerance to AAVrh32.33

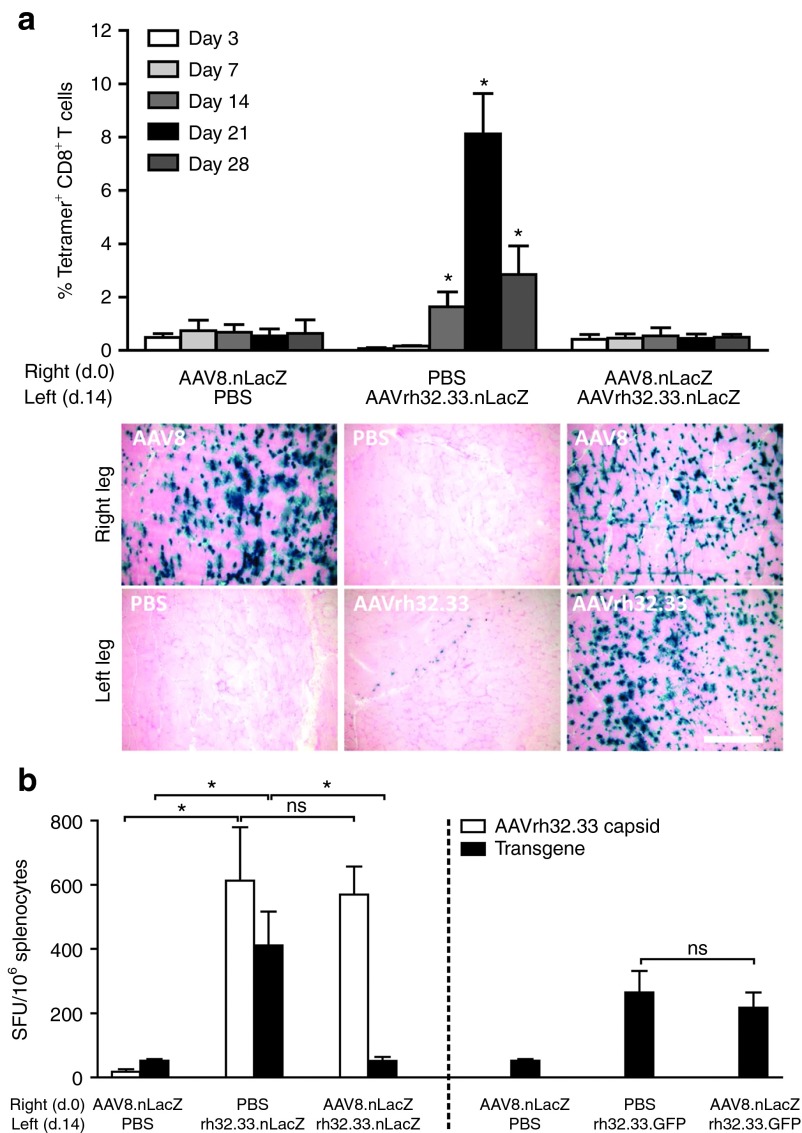

Based on early reports that AAV2 can avoid T cell priming altogether,8 our next objective was to determine whether poor T cell activation to AAV2/8 was also the result of immunological ignorance. To address this, we investigated whether previous exposure to AAV2/8 could induce tolerance to the more immunogenic capsid variant, AAV2/rh32.33. C57BL/6 mice were intramuscularly (i.m.) injected with either PBS as a negative control or 1011 GC of AAV2/8.nLacZ in the right hind leg at day 0. Fourteen days later, mice received either PBS or 1011 GC of AAV2/rh32.33 expressing the same transgene in the opposite leg. Whole blood was harvested from mice at 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days following the second injection, and nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cell responses were monitored by MHCI tetramer staining (Figure 2a). At day 28, mice were killed for histochemical analysis. As expected, AAV2/8.nLacZ alone generates minimal transgene-specific T cell activation, allowing stable β-gal expression in the AAV2/8-injected leg at day 28. AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ alone generated a strong nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cell response, which peaked at day 21 and correlated with a high degree of cellular infiltration in the muscle and weak β-gal expression in the vector-injected leg at day 28 (Figure 2a). Interestingly, however, if mice were previously exposed to AAV2/8.nLacZ, the typical nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cell response expected from AAV2/rh32.33 was completely ablated, allowing for stable β-gal expression to persist in the AAV2/rh32.33-injected muscle at day 28 (Figure 2a). It is important to note that a certain period of time is required between the administration of AAV2/8 and AAV2/rh32.33 in order for AAV2/8 to induce tolerance in the muscle; simultaneous injection of AAV2/8.nLacZ and AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ resulted in the strong nLacZ-specific T cell response and clearance of transduced cells characteristic of AAV2/rh32.33 alone (data not shown).

Figure 2.

AAV2/8 induces transgene-specific tolerance to AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ in the muscle. C57BL/6 mice were injected intramuscularly (i.m.) with PBS or 1011 genome copies (GC) of AAV2/8.CB.nLacZ at day 0 in the right hind leg. 14 days later, mice received an i.m. injection in the opposite leg, containing PBS or 1011 GC of AAV2/rh32.33 expressing either nLacZ (a and b, left panel) or eGFP (b, right panel). (a) At days 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28, whole blood was acquired for nLacZ-specific major histocompatibility complex class I tetramer staining (top panel). At day 28 postinjection, mice were necropsied to harvest muscle for X-gal histochemistry (bottom panel). (b) At the peak of the T cell response, day 28, splenocytes were harvested for interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-ELISPOT. Splenocytes from the left panel were stimulated independently with the dominant H-2Kb CD8+ T cell epitopes for both the AAV8 capsid (data not shown), the AAVrh32.33 capsid (white bars), and the β-gal transgene (black bars). Capsid-specific IFN-γ–producing T cell responses toward the AAV8 capsid were negative for all groups (data not shown). Splenocytes from the right panel were stimulated with the dominant, GFP-specific H-2Kb CD8+ T cell epitope to assess transgene-specific T cell responses to GFP (black bars). Data represent a mean ± SD for four mice per group, where *P ≤ 0.05 compared with (a) PBS or AAV2/8 or (b) the indicated comparisons. Results were confirmed by three independent experiments. (b) Representative tissue sections from four mice per group are shown here under 10× magnification; scale bar represents 250 µm. AAV, adeno-associated virus; nLacZ, nuclear-targeted LacZ; ns, nonsignificant; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

To confirm that AAV2/8-induced tolerance was both capsid and transgene specific, this experiment was repeated, following AAV2/8.nLacZ with a second injection of AAV2/rh32.33 expressing either nLacZ or enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) (Figure 2b, left panel and right panel, respectively). Twenty-eight days following the second injection, mice were killed and splenocytes were harvested for IFN-γ ELISPOT, stimulating against either the AAVrh32.33 capsid or the transgene antigens (left panel, nLacZ; right panel, eGFP). As seen in the left panel of Figure 2b, while the typically robust transgene-specific IFN-γ–producing T cell response to AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ is ablated by previous exposure to AAV2/8.nLacZ, the strong IFN-γ–producing T cell response to the AAVrh32.33 capsid remains unaffected by tolerance to AAV2/8.nLacZ. Capsid-specific IFN-γ–producing T cell responses toward the AAV2/8 capsid were negative for all groups (data not shown). Furthermore, in the right panel of Figure 2b, we show that previous exposure to AAV2/8.nLacZ has no effect on the strong eGFP-specific T cell response generated by AAV2/rh32.33 expressing eGFP. These results confirm that AAV2/8.nLacZ induces capsid- and transgene-specific T cell tolerance in the muscle of C57BL/6 mice.

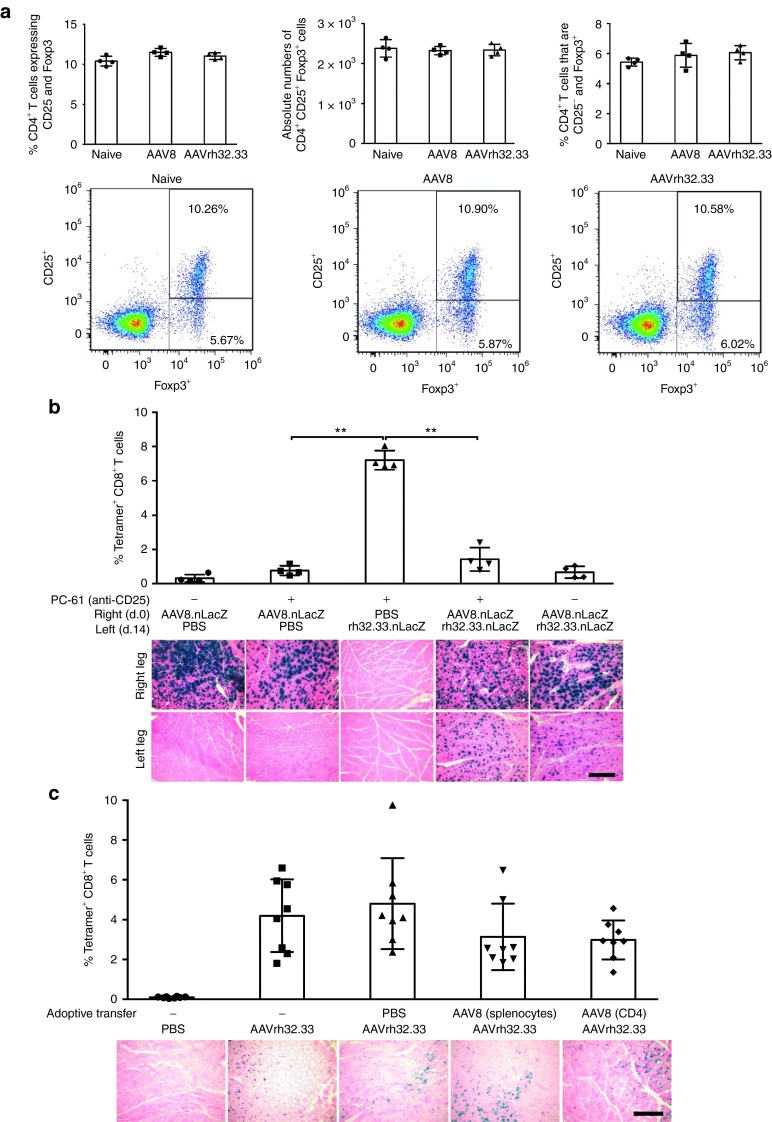

CD4+ Foxp3+ Tregs are not sufficient to cause AAV8-induced tolerance in muscle

The ability of AAV2/8 to induce transgene-specific tolerance to AAV2/rh32.33 indicates that weak T cell activation to AAV2/8.nLacZ in the muscle is not the result of immunological ignorance, but instead a more active mechanism, such as anergy or suppression. Numerous reports in the literature using AAV vectors for hepatic gene transfer have shown evidence of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs capable of suppressing CTL responses.11,15,16 For this reason, we aimed to investigate the role and function of Tregs in immune tolerance to β-gal following i.m. AAV2/8 gene transfer. To address this aim, we first compared expression of CD25 and Foxp3 by CD4+ T cells following i.m. injection of AAV2/8 and AAV2/rh32.33 expressing nLacZ. Splenocytes were harvested at day 21 and stained for CD4, CD25, and Foxp3 by intracellular Foxp3 staining (Figure 3a). Our data show that the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing CD25 and Foxp3 as well as the absolute number of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells did not significantly differ between C57BL/6 mice that received AAV2/8 compared with naive or AAV2/rh32.33-injected mice. Furthermore, there was no significant difference observed in the percentage of CD4+ Foxp3+ cells that were CD25− (Figure 3a). There were also no significant differences in these populations observed between groups at day 14 or day 28 timepoints (data not shown). Overall, these findings suggest that upregulation of CD4+ Foxp3+ Tregs may not play a major role in AAV2/8-induced immune tolerance to β-gal in the muscle. However, it is important to note that alternative suppressive factors, including antigen-specific Treg populations, CD8+ T cells, or soluble factors, may also play a tolerogenic role in this system not accounted for by the current line of investigation. Further studies would be needed to address this potential mechanism.

Figure 3.

A suppressive factor is not sufficient to account for AAV2/8-induced tolerance. (a) Following intramuscular (i.m.) injection of PBS or 1011 genome copies (GC) of either AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing CB.nLacZ, splenocytes were harvested at day 21 and stained for CD4, CD25, and Foxp3 by intracellular Foxp3 staining. Data represent the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing CD25+ and Foxp3+ within the lymphocyte population, as determined by flow cytometry and FlowJo analysis. Representative dot plots were taken from the median of each group. (b) C57BL/6 mice were administered either PBS or the anti-CD25 depleting antibody, PC-61, at days −1 and every 2 weeks thereafter. At day 0, mice were injected i.m. with either PBS or 1011 GC of AAV2/8.CB.nLacZ in the right hind leg. Fourteen days later in the opposite leg, mice received either PBS or 1011 GC of AAV2/rh32.33.CB.nLacZ. At day 21, whole blood was acquired for nLacZ-specific MHCI tetramer staining (top panel) and mice were necropsied to harvest muscle for X-gal histochemistry at day 28 (bottom panel). (c) C57BL/6 mice were injected i.m. with 1011 GC of AAV2/8.CB.nLacZ. At day 21, total splenocytes or sorted CD4+ T cells, by magnetic-activated cell sorting, were isolated and adoptively transferred to naive mice via tail vein injection. The following day, mice were immunized i.m. with 1011 GC AAV2/rh32.33 to determine if a suppressive factor present in the splenocyte or CD4 cell population could blunt the normally strong T cell response seen with AAV2/rh32.33. Twenty-one days after adoptive transfer, whole blood was isolated for nLacZ-specific MHCI tetramer stain (top panel). At day 28 post-transfer, muscle was harvested for X-gal histochemistry (bottom panel). (b) Data represent means ± SD for four mice per group, where **P ≤ 0.01 for the indicated comparisons. Results were confirmed by two independent experiments. (c) Data represent means ± SD for a cumulative n = 8, generated from two independent experiments each with an n of 4. Representative muscle sections from four mice per group are shown here under 10× magnification; scale bars represent 250 µm. AAV, adeno-associated virus; nLacZ, nuclear-targeted LacZ; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

In order to confirm that CD4+CD25+ Tregs were not sufficient for suppressing CD8+ T cell activation, we next depleted mice of CD25+ cells in our model of AAV2/8-induced tolerance to AAV2/rh32.33 using the PC-61 mAb (anti-murine CD25), which is widely used to characterize Treg function in vivo (Figure 3a). In C57BL/6 mice, PC-61 leads to the functional inactivation of Tregs by downregulating CD25 surface expression. In peripheral blood, a single injection of PC-61 mAb (anti-murine CD25) eliminates ˜70% of CD4+Foxp3+ cells with the remaining Tregs expressing low or no CD25.17 To determine whether CD25+ depletion could reverse the established transgene-specific tolerance induced by i.m. injection of AAV2/8, C57BL/6 mice were administered either PBS or the anti-CD25 depleting antibody, PC-61, and injected i.m. with either PBS or 1011 GC of AAV2/8.CB.nLacZ in the right hind leg. After 14 days, mice received either PBS or 1011 GC of AAV2/rh32.33.CB.nLacZ in the opposite leg. The peak nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cell response was monitored by MHCI tetramer stain at day 21 and muscles were sectioned at day 28 to analyze cellular infiltration and expression stability by X-gal histochemical stain (Figure 3b). Our findings indicate that depletion of CD25+ cells was not able to break tolerance and restore the strong transgene-specific T cell response in mice exposed to AAV2/8 prior to AAV2/rh32.33 administration (Figure 3b; PC-61 + AAV2/8 + AAV2/rh32.33). In the absence of CD25+ cells, the nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cell response to mice receiving AAV2/8 followed by AAV2/rh32.33 was still significantly lower than that observed in mice receiving AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ alone (Figure 3b). In comparing groups receiving AAV2/8.nLacZ alone either with or without CD25+ depletion, it appears that treatment with PC-61 correlated with a slight increase in the percentage of nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cells as determined by MHCI tetramer staining. This was also the case when comparing groups receiving AAV2/8 followed by AAV2/rh32.33, either with or without PC-61 treatment. These results suggest that depletion of CD25+ cells results in a slight, but nonsignificant, increase in transgene-specific T cell responses. Despite this slight increase, β-gal expression in the AAV2/8 injected leg was consistently stable (Figure 3a). In addition, in mice previously exposed to AAV2/8, β-gal expression in the AAV2/rh32.33-injected leg was also stable at day 28 with minimal cellular infiltration, which is in stark contrast to the response observed in mice receiving AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ alone (Figure 3b). Ultimately, PC-61-mediated treatment in this study was not sufficient to break AAV2/8-induced tolerance in the muscle. It is important to note that PC-61 can also interfere with the function of activated effector cells, which also transiently express CD25 after activation. As such, it is difficult to fully interpret the in vivo consequences of PC-61 administration following antigen challenge. Further studies will be needed to confirm our findings.

In addition to CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs, other types of Tregs have the ability to mediate CD8+ T cell suppression – for instance, Tr1 cells, a population of antigen-specific regulatory CD4+ T cells which can be elicited in the periphery by antigenic stimulation in the presence of high concentrations of interleukin-10.18,19 The use of flow cytometry and PC-61 depletion could not exclude the potential role of Tr1 cells in AAV2/8-induced tolerance, as this population does not express CD25 or Foxp3.20 To rule out the role of alternative suppressive cell types in AAV2/8-induced tolerance, we next attempted to determine whether adoptive transfer of whole splenocytes or CD4+ T cells was able to transfer the nLacZ-specific tolerance to recipient mice. Tregs can exist as either CD4+ or CD8+ populations, and the presence of tolerogenic dendritic cells (DCs) is also critical in the activation of some subsets. Therefore, it is conceivable that transfer of only CD4+ T cells may not be adequate to completely support the activity of Tregs; hence, only variations of both total splenocytes and sorted CD4+ T cells, by magnetic-activated cell sorting, were used for adoptive transfer. To test for the presence of cells with a suppressive phenotype, C57BL/6 mice were injected i.m. with 1011 GC of AAV2/8.CB.nLacZ. At day 21, we isolated total splenocytes or sorted CD4+ T cells, using magnetic-activated cell sorting, and adoptively transferred them to naive mice via tail vein injection. The following day, mice were immunized i.m. with 1011 GC AAV2/rh32.33 to determine if a suppressive factor present in the splenocyte/CD4 cell population could blunt the normally strong T cell response seen with AAV2/rh32.33 (Figure 3c).

As expected, mice receiving AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ alone, with either no prior adoptive transfer or adoptive transfer of PBS, demonstrated robust nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cell activation at day 21, concomitant with a large degree of cellular infiltration in muscle sections, and levels of β-gal expression beginning to wane at day 28 (Figure 3c). Mice having received adoptive transfer of splenocytes or CD4+ T cells from AAV2/8.nLacZ-injected donors also generated robust nLacZ-specific T cell activation at day 21. These experimental groups did demonstrate a slight decrease in their nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cell responses; however, this trend was not significant and not sufficient to allow stable β-gal expression at day 28 (Figure 3c). Expression levels in these groups appeared slightly higher at day 28 in comparison with groups receiving AAV2/rh32.33 alone; however, a large degree of cellular infiltration was also present in the muscle, suggesting that the kinetics of T cell clearance were merely delayed. Overall, while depletion and adoptive transfer experiments suggest that suppressor cells may slightly effect the frequency of transgene-specific T cell activation, these trends were not able to alter the stability of β-gal expression in our studies, suggesting that a suppressive factor may be necessary, but not sufficient to account for AAV2/8-induced tolerance in the muscle. Further studies to conclusively determine the role of Tregs and additional suppressive factors in this system will be necessary.

AAV8 fails to induce the inflammatory response necessary to prime functional T cells

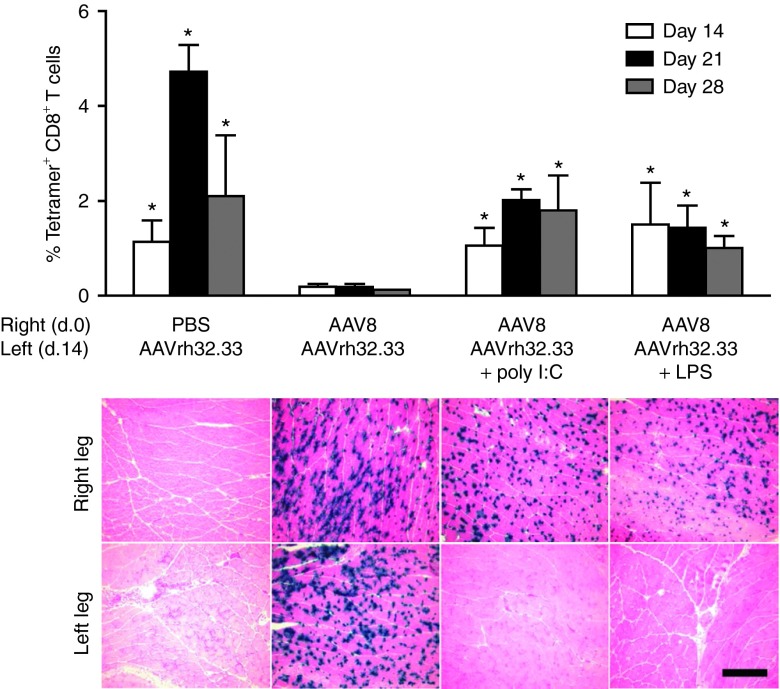

Another potential mechanism of immunological tolerance mediated by AAV2/8 could involve T cell anergy or deletion, in which T cells receive insufficient costimulation or inflammation during priming, resulting in a T cell pool that is either nonresponsive to antigen encounter or undergoes activation-induced cell death.9 We have previously reported that in the absence of CD40-CD40L costimulation, the strong T cell responses generated by AAV2/rh32.33 are lost.2 In many cases, insufficient costimulation is the direct result of poor inflammatory responses leading to poor APC activation. Numerous studies have shown that the addition of exogenous, supplemental inflammation can restore APC activation and, ultimately, break tolerance.13,21,22 Thus, to determine if insufficient inflammatory responses could be playing a role in AAV2/8-mediated tolerance in the muscle, we attempted to break tolerance by delivering AAV2/rh32.33 in the presence of inflammatory adjuvants via coadministration of Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands for 4 consecutive days. Briefly, mice were exposed to AAV2/8 or PBS at day 0 in the right hind leg. Fourteen days later, mice received AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ either alone, or in combination with four daily injections of the ligands for TLR3 (poly I:C) or TLR4 (lipopolysaccharide (LPS)). At days 14, 21, and 28, whole blood was acquired for nLacZ-specific MHCI tetramer staining and mice were necropsied to harvest muscle for X-gal histochemistry. Again, AAV2/rh32.33 alone generated a strong transgene T cell response, which was blunted upon previous exposure to AAV2/8 (Figure 4). Interestingly, AAV2/8-induced tolerance to AAV2/rh32.33 was broken in the presence of LPS and poly I:C, resulting in a significant increase in the nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cell response, and clearance of the majority of β-gal positive fibers from the AAV2/rh32.33-injected muscle by day 28 (Figure 4). Results demonstrate that in the presence of supplemental inflammation, AAV2/8-induced tolerance to AAV2/rh32.33 can be effectively reversed.

Figure 4.

AAV2/8-induced tolerance can be broken in the presence of Toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated inflammation. C57BL/6 mice were injected intramuscularly with either PBS or 1011 genome copies (GC) of AAV2/8.CB.nLacZ in the right hind leg at day 0. Fourteen days later in the opposite leg, mice received 1011 GC of AAV2/rh32.33.CB.nLacZ either alone or in combination with four consecutive injections of the ligands for TLR3 and TLR4, respectively. At days 14, 21, and 28, whole blood was acquired for nLacZ-specific major histocompatibility complex class I tetramer staining (top panel) and mice were necropsied to harvest muscle for X-gal histochemistry (bottom panel). Data represent means ± SD for four mice per group, where *P ≤ 0.05 compared with the “AAV8 + AAVrh32.33” group. Results were confirmed by two independent experiments. Representative muscle sections from four mice per group are shown here under 10× magnification; scale bar represents 200 µm. AAV, adeno-associated virus; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

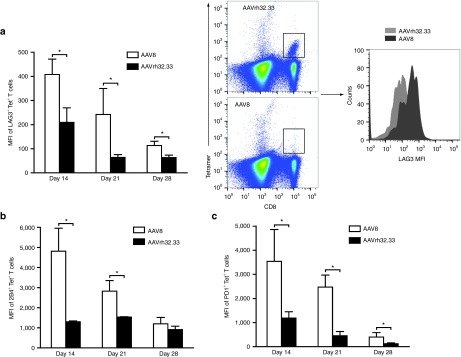

It is important to note that inflammatory stimulation with TLR ligands has been reported to overcome tolerance mediated not only by suppression and T cell anergy/deletion, but also by T cell exhaustion.23 While both anergy and exhaustion are mechanisms of T cell dysfunction, gene expression profiling has determined that they are, indeed, distinct processes.24 In order to asses the role of T cell exhaustion in AAV2/8-mediated T cell dysfunction, C57BL/6 mice were injected with either AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing nLacZ, and characterization of the nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cell population was performed by flow cytometry 14, 21, and 28 days postinjection. Figure 5 illustrates the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of nLacZ-tetramer–positive cells expressing each of the following reported markers of exhaustion: LAG3, 2B4 (CD244), and PD1. Figure 5a also includes representative flow plots detailing the gating strategy used and day 14 MFI data for LAG3 expression (Figure 5a). For both AAV2/8 and AAV2/rh32.33, MFIs were highest 14 days after vector injection, decreasing steadily thereafter. Interestingly, however, at all timepoints, the MFI of LAG3+, 2B4+, and PD1+ nLacZ-tetramer–positive cells was significantly greater for AAV2/8-injected mice when compared with those receiving AAV2/rh32.33 (Figure 5a–c, respectively). These data showed that AAV2/8-induced transgene-specific CD8+ T cells exhibit more robust expression of markers indicative of T cell exhaustion. This is concomitant with a previous functional study documenting significantly reduced production of IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-2 cytokines following antigenic stimulation in splenocytes isolated from AAV2/8.nLacZ- versus AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ-injected mice.2

Figure 5.

AAV2/8 primed T cells exhibit markers of exhaustion. C57BL/6 mice were injected intramuscularly with 1011 genome copies of either AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing nuclear-targeted LacZ (nLacZ). Splenocytes were harvested for flow cytometry, 14, 21, and 28 days postinjection. Data represent MFI of (a) LAG3, (b) 2B4 (B), (c) PD1 and nLacZ-tetramer double positive T cells. Data represent means ± SD for four mice per group, where *P ≤ 0.05 for the indicated comparisons. AAV, adeno-associated virus; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity.

AAV8 fails to upregulate MHCI expression on target cells, rendering transduced myocytes poor targets for CTL-mediated clearance

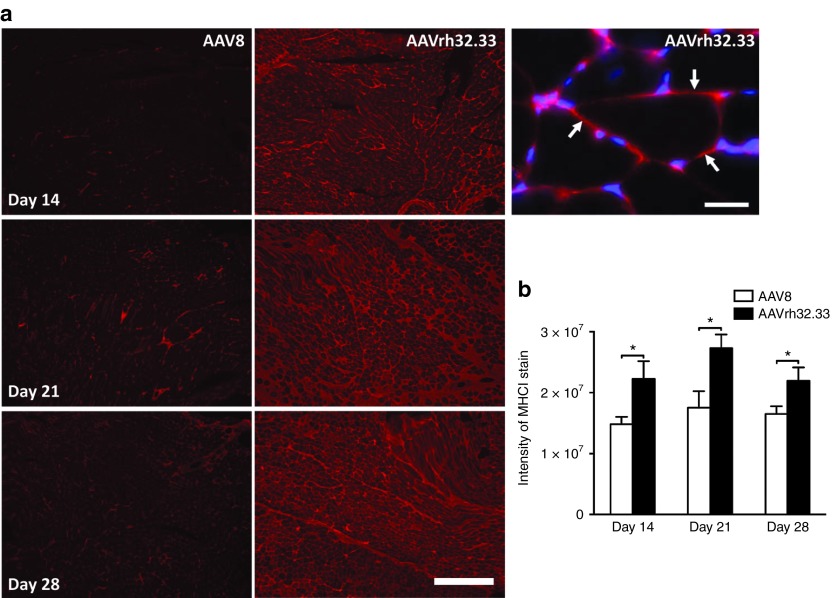

Interestingly, in our model of AAV2/8-induced tolerance in the muscle, even though coadministration of AAV2/rh32.33 in the presence of TLR-mediated inflammation restores transgene-specific T cell responses to levels sufficient to clear transduced cells in the AAV2/rh32.33-injected leg, β-gal positive muscle fibers are still observed in the AAV2/8-injected leg (Figure 4). This finding suggests that circulating T cells are unable to clear AAV2/8-transduced myocytes in the opposite leg (Figure 4). This observation suggests that muscle cells transduced with AAV2/8.nLacZ may be poor targets for T cell-mediated killing. Previous studies in the liver have shown that AAV transduction lacks the inflammatory signals necessary to render hepatocyte targets for CTLs.13 Therefore, we next hypothesized that AAV2/8 transduction in the muscle was not capable of upregulating sufficient expression of molecules involved in displaying antigen on the cell surface, namely MHCI. To test this hypothesis, 1011 GC of either AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing nLacZ were injected into the muscle of C57BL/6 mice, which were then killed at days 14, 21, and 28 to analyze surface expression of MHCI on myocytes (Figure 6). At all timepoints, AAV2/rh32.33-injected mice demonstrated robust MHCI staining in muscle sections, compared with negative control sections stained with normal C57BL/6 mouse serum (Figure 6a and data not shown). In comparison to AAV2/rh32.33, AAV2/8-injected muscles showed minimal expression of MHCI (Figure 6a). A high magnification image of an AAV2/rh32.33-injected mouse stained against both MHCI (red) and a 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear stain (blue) shows that while areas infiltrated with lymphocytes also stain positive for MHCI, we observed clear MHCI staining surrounding the muscle fibers without being restricted to individual nuclei (Figure 6a). The intensity of MHCI staining within muscle sections was quantified (Figure 6b), confirming that MHCI expression on AAV2/8.nLacZ-transduced cells is significantly lower than that observed in the muscle of mice injected with AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ (Figure 6b). DAPI staining showed a comparable number of nuclei per section between AAV2/8- and AAV2/rh32.33-injected muscle sections (data not shown). This suggests that AAV2/8 injection into the muscle elicits poor upregulation of MHCI on transduced myocytes, preventing proper antigen presentation on the cell surface, and making transduced cells poor targets for CTL-mediated destruction.

Figure 6.

AAV2/8 shows reduced MHCI expression on the surface of myocytes in comparison to AAV2/rh32.33. C57BL/6 mice were injected intramuscularly with 1011 genome copies of either AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing nLacZ. Mice were killed and muscles were isolated, 14, 21, and 28 days postinjection. (a) Muscle sections were blocked with avidin and biotin, treated with mouse-specific blocking solution, and stained with monoclonal antibody 5041.16.1 (anti-MHCI) diluted 1:50 for 1 hour followed by biotinylated anti-mouse antibodies and rhodamin-avidin; scale bar represents 500 µm. Scale bars for the image with DAPI costaining represent 25 µm. For controls, primary antibodies were replaced by normal sera from C57BL/6 mice (1:1000), or BALB/C muscle sections (haplotype d) were stained with the haplotype b-specific antibody (data not shown). (b) To quantify MHCI expression, a low magnification image (4× objective) was taken from each muscle section stained for H-2K/H-2D. The brightness values of the images (i.e., the sum of all pixel values of each image) were determined with ImageJ software and averaged for each group. Experiments were performed with an n of four mice per group (*P ≤ 0.05) for the indicated comparisons. AAV, adeno-associated virus; MHCI, major histocompatibility complex class I.

Upstream: ineffective T cell priming is the result of poor APC transduction and activation by AAV8

Dysfunctional adaptive immune responses are often the result of insufficient innate immune activation or poor transduction, activation, and maturation of APCs. AAV2 vectors have been reported to display reduced innate immunity and APC transduction when compared with more immunogenic adenoviral vectors,25,26 as well as inefficient recruitment and activation of CD11c+ DCs following i.m. injection.27 Collectively, these studies suggest that AAV2 avoids upregulation of the molecules critical for T cell priming, including signal 1 (MHCI/II), signal 2 (CD80/86), and signal 3 (inflammatory cytokines). A recent report indicated that adaptive immunity to AAV1, 2, and 9 vectors was dependent upon innate immune activation through the TLR9/MyD88 pathway to stimulate type I IFNs.28 To assess whether decreased APC transduction may play a role in the dysfunctional adaptive immune responses observed to AAV2/8 in the muscle, AAV2/8 and AAV2/rh32.33 vectors expressing eGFP were first added to JAWSII murine DC cultures in vitro at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 107 GC/cell (Figure 7a). Four days post-transduction, AAV2/8.eGFP demonstrated minimal GFP expression under 10× magnification, only slightly above the PBS negative control (Figure 7a). AAV2/rh23.33.eGFP, on the other hand, showed a notable increase in GFP positivity, slightly lower than what was seen for the Ad5.eGFP positive control. A similar result was also observed in murine macrophage cells (RAW 264.7), following transduction with PBS, AAV2/8, or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing firefly luciferase (ffLuc) (Figure 7b). AAV2/8.ffLuc-transduced cells showed minimal luciferase expression above background, in contrast with a significant increase in luciferase expression for AAV2/rh32.33.ffLuc-transduced RAW 264.7 cells when compared with either PBS or AAV2/8-transduced cells.

Figure 7.

AAV2/8 shows reduced in vitro transduction and in vivo activation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). (a) AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing enhanced GFP (eGFP) was used to transduce JAWSII murine dendritic cells (DCs) (top two panels) at a multiplicity of infect (MOI) of 1 × 107 genome copies (GC)/cell. PBS and Ad5.eGFP were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 vectors were used to cotransduce U937 human monocyte derived DCs (bottom panel) at an MOI of 1 × 106 with wtAd5 (MOI: 1 × 104) and anti-Ad5 antibody (1/8,000). Images were taken 4 days post-transduction. Scale bar is estimated to represent 50 µm. (b) RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cells were transfected with vector expressing firefly luciferase. (c) Transduced U937 cells were then run on a flow cytometer and gated for GFP fluorescence (FL1) to compare mean fluorescence intensity between cells transduced with AAV2/8 versus AAV2/rh32.33 (representative image shown). (d–f) C57BL/6 mice were injected intramuscularly with 1011 GC of AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing nLacZ. At 12 hours postinjection, spleen, popliteal, and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested and stained for antibodies against the DC marker CD11c, and the APC activation markers, CD80/86, CD40, and MHCII. (d) The percentage of CD11c+ DCs in the total cell population within each tissue 12 hours postinjection. (e) The percentage of expression of DC activation markers within the popliteal lymph node 12 hours postinjection. (f) Representative histograms demonstrating differential expression of surface molecules typically upregulated on activated DCs; taken from the popliteal lymph node at 12 hours. An intraperitoneal injection of LPS, a known activator of innate immunity, was used as a positive control. Experiments were performed in triplicate (in vitro) or with an n of four (in vivo) and repeated in at least two independent studies. Data are shown as mean ± SD; *P ≤ 0.05 for the indicated comparisons as shown in b, or when compared with PBS or AAV2/8 groups as shown in d,e. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MHCII, major histocompatibility complex class II; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

We next wanted to confirm these results in U937 cells, a human monocyte-derived cell line. AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing eGFP were added to U937 cells at an MOI of 106, in combination with wild-type Ad5 help (MOI 104) and anti-Ad5 antibody (at 1/8,000) to enhance transduction. Four days post-transduction, the expression of GFP in the cell cultures were determined by fluorescence microscopy under 10× magnification as well as flow cytometry (Figure 7a,c). As seen with the JAWSII murine DCs, U937 human monocytes showed substantially reduced transduction by AAV2/8 vector, in comparison to AAV2/rh32.33. Taken together, this confirms the hypothesis that AAV2/8 shows diminished transduction of APCs in vitro. Poor APC transduction by AAV2/8 likely decreases the activation of innate and adaptive immunity, contributing to AAV2/8's tolerance induction in the muscle and the activation of dysfunctional transgene-specific CD8+ T cells.

Our next objective was to determine whether decreased transduction of APCs by AAV2/8 in comparison to AAV2/rh32.33 in vitro correlated with differential recruitment and activation of those APCs in vivo. To assess the ability of AAV2/8 to recruit circulating APCs to spleen and draining lymph nodes following i.m. injection, AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing nLacZ were injected into the muscle of C57BL/6 mice at a dose of 1011 GC. PBS and LPS were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. At 12 hours after vector administration, splenocytes, popliteal, and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested and cells stained for CD11c, CD80/86, CD40, and MHCII (Figure 7d–f). Figure 7d represents the percentage of CD11c+ DCs gated in the total cell population in all three harvested tissues. It appears that, both in spleen and draining lymph nodes, AAV2/rh32.33 and the LPS positive control significantly enhanced the percentage of circulating CD11c+ DCs above background; whereas, AAV2/8-injected mice showed comparable percentages of CD11c+ DCs as PBS-injected controls (Figure 7d). In the popliteal lymph node population 12 hours postinjection, AAV2/8-injected mice actually appeared to downregulate the frequency of CD11c+ DCs, though this trend was not observed in later timepoints, at 24 or 96 hours postinjection (Figure 7d and Supplementary Figure S2a,b). In all tissues, the percentage of CD11c+ DCs was significantly lower for AAV2/8 when compared with AAV2/rh32.33 (Figure 7d). At later timepoints, the significant difference in CD11c+ DC frequency between AAV2/8- and AAV2/rh32.33-injected mice was only observable in spleen at 24 hours, or in inguinal lymph nodes at 96 hours (Supplementary Figure S2a,b). The significant increase in CD11c+ DC frequency observed in popliteal lymph nodes 12 hours after AAV2/rh32.33 injection was no longer observable at 24- or 96-hour timepoints. In addition, some elevation in infiltrating CD11c+ cells over background did occur in AAV2/8-injected mice at later timepoints (Supplementary Figure S2a,b).

This discrepancy in the ability of AAV2/8 and AAV2/rh32.33 to recruit CD11c+ DCs to the spleen and draining lymph nodes led us to question the activation status of the DC population within these tissues. Figure 7e,f represents staining of CD11c+ DC activation markers in the popliteal lymph node samples harvested 12 hours after vector injection (Figure 7e–f). Ultimately, injection of AAV2/rh32.33 and LPS resulted in a significant upregulation in the percentage of CD11c+ DCs capable of expressing CD80/86, CD40, and MHCII. Conversely, injection of AAV2/8 resulted in no upregulation of activation makers over background, as the percentage of CD80/86, CD40, and MHCII expression within the CD11c+ population was comparable to our PBS negative control (Figure 7e). This finding was consistent at both 24- and 96-hour timepoints (Supplementary Figure S2c,d). In terms of CD40 expression, AAV2/8 appeared to downregulate surface expression of this critical costimulatory molecule in the CD11c+ DC population 12 hours after vector administration (Figure 7e). Representative histograms demonstrating differential expression of CD11c+ DC activation markers at 12 hours are shown in Figure 7f. Representative 2D dot plots from these samples are also shown in Supplementary Figure S3. As with the LPS positive control, AAV2/rh32.33 resulted in a significant increase in the percentage of CD11c+ DCs expressing all three activation markers at both the 12- and 24-hour timepoints (Figure 7e and Supplementary Figure S2c). In conclusion, it appears that, in comparison to AAV2/rh32.33, AAV2/8 reduces the recruitment and activation of CD11c+ DCs at early timepoints, preventing the upregulation of molecules playing a critical role in functional T cell priming through both antigen presentation and costimulation.

Vector leakage to liver following i.m. injection

As numerous studies have demonstrated the induction of tolerance following hepatic gene transfer of AAV vectors, we were interested to determine whether leakage of vector to the liver following i.m. injection was occurring in our system.12,15,16 As seen in Supplementary Figure S1, we observed a large degree of eGFP expression in the liver 14 days following i.m. injection of AAV2/8.CB.eGFP. As transgene product expression occurs not only in the muscle, but also in liver, future studies will be necessary to determine the effect of liver expression on tolerance induction in this system.

Discussion

Numerous studies have confirmed the ability of AAV vectors to evade immune activation to highly antigenic, nonself transgenes, allowing for stable, long-term transgene expression.3,4,5,6,7 Unfortunately, it is also clear that this state of tolerance can be threatened by numerous factors, including host species, capsid serotype, and target tissue. As such, understanding the delicate balance between tolerance induction and immune activation is critical to the safe translation of gene therapy strategies to the clinic. By characterizing the mechanisms of AAV8-induced tolerance induction in the muscle, we offer an additional perspective on the number of AAV:host cell interactions that contribute to the activation or evasion of immunity.

Several studies have documented cases where transgene-specific CD8+ T cells are primed, but nonfunctional in terms of clearing transduced cells. Recent work by Velazquez et al. showed a strong transgene-specific CD8+ response following i.m. delivery of AAV8; however, upon migration to the muscle, these cells underwent functional impairment following by programmed cell death.29 Alternatively, transgene-specific CD8+ T cells primed in response to AAV7 and AAV8 vectors in two vaccination studies documented a state of exhaustion, where T cells were not deleted, but became functionally impaired upon antigen restimulation.14,30 Our earlier work has shown that in the case of AAV8, generation of a strong CD8+ T cell response can often be avoided altogether due to a lack of proper costimulation and CD4+ T cell help during early T cell priming. Here, we have shown that in the muscle, AAV2/8 evades immune activation from even the earliest stages of vector interaction with the host by poorly transducing APCs. A decrease in APC transduction reduces the amount of endogenous antigen available for processing and direct presentation onto MHCI for the priming of naive T cells. This finding is concurrent with reports that other AAV serotypes demonstrate poor APC transduction, requiring the less efficient cross-presentation pathway to function in the loading of transgene antigens onto MHCI for CD8 priming.8,31 Concurrent with many reports comparing innate immune induction of AAV versus adenoviral vectors,25 AAV2/8 also avoids the activation of type I IFNs, which has been shown to result following TLR9/MyD88 signaling in response to AAV1, 2, and 9.28 In concert with poor APC transduction, avoidance of innate inflammation reduces the recruitment and activation of APC populations and proper upregulation of molecules critical to antigen processing and presentation.32,33 We observed that in vivo transduction of AAV2/8 showed minimal recruitment of CD11c+ DCs to spleen and draining lymph nodes, as well as reduced surface expression of the CD11c+ activation markers MHCII, CD80/86, CD40 in comparison with AAV2/rh32.33. These data support previous findings that AAV2 vectors show poor upregulation of MHCII or CD80/86 on the surface of CD11c+ DCs.27 Limited MHCII upregulation may prevent priming of CD4+ T helper cells, which have been shown to play a critical role in CD8+ T cell activation, effecting either initial CD8 priming, or the establishment of functional CD8 memory. This is supported by our previous findings that AAV2/8 shows minimal CD4+ infiltration in comparison with AAV2/rh32.33.2 Furthermore, without the expression of proper costimulatory molecules, such as CD80/86 or CD40, T cells are primed in the absence of signal 2, resulting in an anergic phenotype. The importance of CD40-CD40L costimulation in successful CD8+ T cell priming to AAV2/rh32.33 has also been reported.2

Overall, the ability of supplemental, TLR ligand-mediated inflammation to overcome tolerance confirms that AAV2/8 alone fails to induce the inflammatory response necessary to prime a functional class of CD8+ T cells and initiate CTL-mediated clearance of transduced cells. Interestingly, even in the presence of TLR ligands, when the T cell response to AAV2/rh32.33 is restored, those T cells are only capable of clearing cells transduced by AAV2/rh32.33, but not those transduced by AAV2/8. It is important to note that the absence of a sufficient inflammatory response to AAV vectors prevents proper upregulation of antigen presentation machinery not only in the APC population itself, but also in target cells. While poor upregulation of these molecules in DCs diminishes functional T cell priming, poor expression on non-APC populations makes AAV-transduced cells poor targets for CTL-mediated clearance. Our studies demonstrate that, compared with AAV2/rh32.33, delivery of AAV2/8 to the muscle results in a reduction of MHCI upregulation on the surface of myocytes. This finding is concomitant with our previous work showing that poor inflammatory responses prevent proper upregulation of MHCI on hepatocytes following AAV2/8 delivery to the liver.13 As such, the immune response to AAV2/8 in the muscle can be viewed as one involving minimal inflammation, with insufficient APC transduction and poor upregulation of the molecules required for both T cell priming and target cell recognition.

If antigen load, APC activation, and maturation do not reach a critical level, insufficient antigen would be presented to the naive T cell pool, resulting in immunological ignorance. This phenotype has been previously described for AAV2.8 In our studies, however, the ability of AAV2/8 to induce transgene-specific tolerance to AAV2/rh32.33.nLacZ clearly shows that ignorance is not the prevailing method of tolerance at work in this system. AAV2/8 is not avoiding T cell priming altogether, but instead priming dysfunctional T cells or perhaps a class of suppressors. Due to the well-documented role of Tregs in hepatic tolerance to AAV, we attempted to determine the role of suppression in our system. Depletion and adoptive transfer experiments were unable to rule out the involvement of a regulatory population, suggesting instead that a suppressive factor may be necessary, but was not sufficient to explain AAV2/8-mediated tolerance in the muscle of our studies. Future studies will be needed to confirm these findings and further elucidate the potential role of active suppression in this system. As an alternative to suppression, aberrant T cell functionality would be another likely cause of the phenotype observed. Additional reports in the literature support the hypothesis that AAV vectors injected into the muscle can prime a class of functional aberrant T cells,14,30 and that muscle-directed gene transfer does not result in Treg induction.34

The ability to break tolerance by supplementing immune activation with TLR ligands indicates that the small number of T cells primed to AAV2/8 are likely either anergic/deleted or exhausted. Characterization of the phenotype of this T cell population indicates that, compared with AAV2/rh32.33, AAV2/8-primed T cells display significantly more robust expression of the inhibitory receptors PD1, LAG3, and 2B4 (CD244), which are recognized markers of exhaustion. Previous work supports this hypothesis by showing that nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cells primed in response to AAV8.nLacZ were unable to produce IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, or interleukin-2 above background levels.2 This was in contrast to AAVrh32.33.nLacZ vectors, which generated nLacZ-specific CD8+ T cells with a significant increase in production of all three cytokines when compared with PBS-injected mice 21 days after i.m. administration.2 This phenotype was also observed following injection of AAV2/7 into the muscle, and has been reported in many systems where chronic, persistent antigen expression cannot be overcome by CTLs, resulting in a T cell population which demonstrates decreasing functionality over time and upregulation of these inhibitory receptors.14,35 Though the exhaustion phenotype has been found to be transcriptionally distinct from T cell anergy, reports that early PD1 upregulation can induce anergic CD8+ T cells in vivo suggests that the two phenotypes may be closely linked.24,36 Further studies will be necessary to fully characterize the distinctions between T cell anergy and exhaustion, especially as they relate to AAV-induced tolerance in vivo. Taken together, it is conceivable that effector T cells primed to the nLacZ transgene circulate to the muscle, where, due to poor antigen display on transduced myocytes, they are unable to kill the majority of transduced cells. As a result, in the presence of persistent, undiminishing antigenic stimulation, these effector cells become quickly exhausted, mirroring the phenotype commonly seen in response to chronic viral infections such as lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus.37

Importantly, numerous studies have shown that hepatic gene transfer of AAV vectors can induce transgene-specific tolerance.12,15,16 Therefore, it is possible that vector dissemination to the liver after i.m. injection may support the induction of immune tolerance as well. Indeed, leakage of both eGFP and ffLuc expression from muscle to liver after i.m. injection of AAV8 has been observed.38 As such, the effect of hepatic expression on tolerance induction in this system will be an important line of future investigation. The use of a muscle-specific promoter, for instance, may be helpful in delineating the immune effects of AAV8.nLacZ circulation and gene expression in the liver.

Overall, we believe there is a threshold required for the activation of functional CD8+ effectors, where numerous factors contribute to either helping AAV overcome this threshold or keeping it below the critical level, resulting in tolerance. The early ability of the AAV vector to induce innate inflammation, transduce, and activate APCs largely dictates whether or not this threshold is met. Higher order species, more immunogenic capsids, and tissues with a greater degree of regeneration and inflammation are known to more readily generate immune activation to AAV vectors. Here, we demonstrate that AAV2/8 delivery to the muscle of C57BL/6 mice results in poor APC transduction, recruitment, and upregulation of CD80/86, CD40, and MHCI and II, limiting CD8+ T cell priming and preventing proper antigen display on target cells. This leads to the priming of a dysfunctional class of CD8+ T cell effectors, which (unable to recognize their targets) are rapidly exhausted, perpetuating the phenotype of stable expression following AAV2/8 transduction in muscle. Future studies will certainly continue to further elucidate the nuances of the immune response to AAV in various settings with the ultimate goal of establishing a thorough understanding of the threshold between establishing tolerance and generating immunity. The ability to predict and circumvent deleterious cellular responses is essential to the safe and efficacious translation of AAV vectors into the clinic.

Materials and Methods

Vector production and purification. Recombinant AAV vector with the AAV8 or AAVrh32.33 viral capsid expressing nuclear-targeted LacZ (nLacZ) or eGFP was manufactured as described previously39 by Penn Vector at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA). Briefly, an AAV cis-plasmid containing transgene cDNA driven by the chicken β-actin (CB) promoter (or cytomegalovirus promoter for eGFP vectors) and flanked by AAV2 inverted terminal repeats was packaged by triple transfection of HEK293 cells using an adenovirus helper plasmid (pAdΔF6), and a chimeric packaging construct containing the AAV2 Rep gene and the AAV8 or AAVrh32.33 Cap gene. Vectors were purified by cesium chloride gradient centrifugation. The genome titer (GC per ml) of AAV vectors was determined by real-time PCR.

Animals. Male C57BL/6 mice, aged 6–8 weeks, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were maintained in the Animal Facility of Translational Research Laboratories. All experimental procedures involving the use of mice were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania.

Animal treatments. Mice were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (70 and 7 mg/kg of body weight, intraperitoneally (i.p.)); 1011 GC of recombinant AAV vector was injected into the anterior tibialis muscle in a volume of 50 µl of sterile PBS. For TLR ligand administration, the following concentrations were used: LPS: 50 µg; poly I:C: 100 µg. All TLR ligands (Invivogen, San Diego, CA) were injected i.p. in a final volume of 100 µl, diluted in endotoxin free water. Ligands were administered on the day of AAV2/rh32.33 i.m. injection, and for 3 additional days thereafter for a total of 4 consecutive days of administration. The PC-61 monoclonal antibody was injected i.p. at a concentration of 500 µg, starting 2 days before vector administration, and continued every 2 weeks thereafter. Where indicated, whole blood was extracted by retro-orbital bleeds using a heparinized capillary tube in the lateral canthus of the eye, on lightly anesthetized animals (35 and 5 mg/kg, i.p. of ketamine-xylazine). At various timepoints after vector injection mice were killed by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation to harvest spleen and muscle.

Adoptive transfer. Six- to eight-week-old age-matched male C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory) were injected i.m. with 1011 GC of AAV2/8.nLacZ. At day 21, splenocytes were harvested, and CD4 T cells were isolated using MACS cell separation kits (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). The purity of the isolated cells was >95% as determined by subsequent flow cytometry (fluorescence-activated cell sorting) analysis. Freshly isolated splenocytes or CD4 cells (2–4 × 106/mouse) were adoptively transferred to naive C57BL/6 mice via intravenous tail vein injection.

APC transduction and activation studies. JAWSII murine DCs were transduced by eGFP expressing vectors at an MOI of 1 × 107 GC/cell. Mouse macrophage cells (RAW 264.7) were transduced at an MOI of 1 × 106 GC/cell by vectors expressing ffLuc. U937 human monocyte-derived DCs were cotransduced at an MOI of 1 × 106 with AAV.eGFP vector, wtAd5 (MOI: 1 × 104), and anti-Ad5 antibody (1/8,000). Fluorescence microscopy images were taken 4 days post-transduction. Transduced U937 cells were run on the flow cytometer and gated for GFP fluorescence (FL1) to compare MFI. For in vivo activation studies, C57BL/6 mice were injected i.m. with 1 × 1011 GC of AAV2/8 or AAV2/rh32.33 expressing nLacZ. At 12 hours postinjection, spleen, popliteal, and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested and stained for antibodies against the DC marker CD11c, and the APC activation markers, CD80/86, CD40, and MHCII. An i.p. injection of LPS was used as a positive control.

MHCI tetramer staining. PE-conjugated MHCI H2-Kb-ICPMYARV tetramer complex was obtained from Beckman Coulter (Fullerton, CA). At various time points after vector injection, tetramer staining was performed on heparinized whole blood cells isolated by retro-orbital bleeds. Cells were costained for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT) with PE-conjugated tetramer and FITC-conjugated anti-CD8α (Ly-2) antibody (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Red blood cells were then lysed and cells were fixed with iTAg MHC tetramer lysing solution supplemented with fix solution (Beckman Coulter) for 15 minutes at RT. The cells were then washed three times in PBS and resuspended in 0.01% BD CytoFix (BD Biosciences). Data were gathered with an FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL) and were analyzed with FlowJo analysis software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA). In the analysis, lymphocytes were selected on the basis of forward and side scatter characteristics, followed by selection of CD8+ cells, and then the tetramer-positive CD8+ T cell population.

Intracellular Foxp3 staining. Spleens harvested from treated mice were transferred into Liebowitz's-15 (L-15; Cellgro, Mediatech, Herndon, VA) at RT. The tissue was then homogenized and passed through a 70-µm nylon cell strainer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) to remove cell clumps and un-dissociated tissue. The cells were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 1,600 rpm at RT, resuspended in fresh L-15 media, and centrifuged again. The cell pellet was resuspended in T cell assay media (DMEM; (Cellgro, Mediatech), 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Hyclone; Logan, UT), 1% Pen-Strep (Cellgro, Mediatech), 1% L-Glutamine, 10 mmol/l HEPES (Cellgro, Mediatech), 0.1 mmol/l nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), sodium pyruvate, and 10–6 mol/l 2-mercaptoethanol (Cellgro, Mediatech)).

Harvested splenocytes were stained using the Mouse Regulatory T cell Staining Kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 100 µl of prepared cells (106 cells/well) were plated in a 96-well plate. Cells were stained using anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 antibodies (eBioscience) for 20 minutes at 4 °C. After washing, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and subsequently stained with anti-Foxp3 (eBioscience) for 45 minutes at 4 °C. After washing, cells were examined by flow cytometric analysis. Samples were acquired on an FC500 (Beckman-Coulter) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

IFN-γ ELISPOT. Splenocytes from treated mice were harvested as described above. Following isolation and washing steps splenocytes were overlaid onto a Ficoll-Paque (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) gradient layer and centrifuged for 20 minutes at 2,000 rpm at RT in order to remove red blood cells. The lymphocyte band was then recovered and further washed two times in PBS/1% fetal bovine serum.

To determine the number of cells secreting IFN-γ in response to antigenic stimulation, an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences). Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with capture antibody overnight at 4 °C and blocked for 2 hours at 25°C with Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 1% Pen-Strep-L-Glut. Splenocytes were plated at two densities (105 and 2.5 × 105 cells/well) in T cell assay media supplemented with 1 µg/ml of the nLacZ dominant peptide (ICPMYARV; Mimotopes, Victoria, Australia), 2 µg/ml of the AAV8 capsid peptide library, or 2 µg/ml of the dominant AAVrh32.33 capsid CD8 H2-Kb T cell epitope40 (SSYELPYVM; Mimotopes). PMA/Ionomycin (PMA: 0.05 µg/ml; Ionomycin: 1 µg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used to stimulate a separate population of lymphocytes (plated at 2 × 104/well) as a nonspecific, positive control. Cells plated in media alone (no peptide stimulation) served as a negative control. Plates were incubated for 18 hours at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Following incubation, plates were washed vigorously in deionized water, PBS/0.05% Tween-20 (Sigma), and incubated for 2 hours at RT with 2 µg/ml of biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ detection antibody. Following three washes with PBS/0.05% Tween-20, the plates were incubated with 5 µg/ml of enzyme conjugate (streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase) for 1 hour at RT. Following a series of washes with PBS/0.05% Tween-20 and PBS, spots were developed using the AEC Substrate Set (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Color development was stopped after 8 minutes by washing with distilled water. Plates were dried overnight at RT and read using the AID ELISPOT reader system (Cell Technology, Columbia, MD). Responses >200 spot-forming units or at least 2 logs over background were considered.

Histology and transgene detection. To examine expression of nuclear β-galactosidase, X-gal staining on cryosections from snap frozen muscles was performed according to standard protocols.41 Sections were slightly counterstained with Fast Red to visualize nuclei. Muscles expressing GFP were fixed over night in formalin, washed in PBS for several hours, and then snap frozen for sectioning. Cryosections were mounted in Vectashield containing DAPI (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) to show nuclei.

Analysis of MHCI expression. To detect expression of H-2K/H-2D, sections (8 µm) from frozen gastrocnemius muscle were fixed at −20 °C in acetone for 5 minutes and processed using a “mouse on mouse” kit (Vector Laboratories) to prevent unspecific binding of mouse antibodies onto mouse tissue. Briefly, the sections were blocked with avidin and biotin, treated with mouse-specific blocking solution, and stained with monoclonal antibody 5041.16.1 (Cedarlane Laboratories, Burlington, NC) diluted 1:50 for 1 hour followed by biotinylated anti-mouse antibodies and rhodamin-avidin. All dilutions were made in PBS containing the respective blocking agent and samples were washed between incubation steps with PBS. For controls, primary antibodies were replaced by normal sera from the same species from which the primary antibody originated, at a 1:1,000 dilution. As an additional control for the haplotype b-specific antibody against H-2K/H-2D, muscle sections from BALB/c mice (i.e., haplotype d) were stained using the same protocol.

To quantify MHCI expression, a low magnification image (4× objective) was taken from each muscle section stained for H-2K/H-2D. The brightness values of the images (i.e., the sum of all pixel values of each image) were determined with ImageJ software (Wayne S Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) and averaged for each group.

Statistical analysis. Calculations were performed using Graph Pad Prism 5.0 software. Statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05) was determined using the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Intramuscular delivery of AAV2/8 results in leakage to the liver. Figure S2. In vivo activation of APCs at 24- and 96-hour timepoints. Figure S3. APC frequency and activation in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Animal Models Program and Cell Morphology Core (University of Pennsylvania Gene Therapy Program) for help with the animal studies, processing of tissue samples, and histological staining. We also thank Penn Vector at the University of Pennsylvania for providing the vectors used in this research. Additional thanks go to Yiping Yang at the Department of Immunology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC for personal communication and studies regarding innate immune activation by AAV2/8 and AAV2/rh32.33 and to Michael Kormann at the University of Tübingen for assistance with statistical analysis. This research was supported by grants from NICHD P01 HD57247 and NIDDK P30 DK47757 (J.M.W.) as well as NIH T32-AR-053461-03 and T32-AI-007324-17 (L.E.M.). J.M.W. is a consultant to ReGenX Holdings, and is a founder of, holds equity in, and receives a grant from affiliates of ReGenX Holdings; in addition, he is an inventor on patents licensed to various biopharmaceutical companies, including affiliates of ReGenX Holdings. L.E.M. is currently at the Department of Translational Genomics and Gene Therapy, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany. This work was performed in Philadelphia, PA. Part of the information included in this paper was presented in The Twelfth Annual Meeting of the American Society of Gene Therapy that was held in San Diego, CA, 27–30 May 2009, Oral Abstract #769. All the other authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zaiss AK, Muruve DA. Immunity to adeno-associated virus vectors in animals and humans: a continued challenge. Gene Ther. 2008;15:808–816. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays LE, Vandenberghe LH, Xiao R, Bell P, Nam HJ, Agbandje-McKenna M, et al. Adeno-associated virus capsid structure drives CD4-dependent CD8+ T cell response to vector encoded proteins. J Immunol. 2009;182:6051–6060. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder RO, Miao C, Meuse L, Tubb J, Donahue BA, Lin HF, et al. Correction of hemophilia B in canine and murine models using recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat Med. 1999;5:64–70. doi: 10.1038/4751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acland GM, Aguirre GD, Bennett J, Aleman TS, Cideciyan AV, Bennicelli J, et al. Long-term restoration of rod and cone vision by single dose rAAV-mediated gene transfer to the retina in a canine model of childhood blindness. Mol Ther. 2005;12:1072–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotte TR, Afione SA, Conrad C, McGrath SA, Solow R, Oka H, et al. Stable in vivo expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator with an adeno-associated virus vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10613–10617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplitt MG, Leone P, Samulski RJ, Xiao X, Pfaff DW, O'Malley KL, et al. Long-term gene expression and phenotypic correction using adeno-associated virus vectors in the mammalian brain. Nat Genet. 1994;8:148–154. doi: 10.1038/ng1094-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai H, Herzog RW, Hagstrom JN, Walter J, Kung SH, Yang EY, et al. Adeno-associated viral vector-mediated gene transfer of human blood coagulation factor IX into mouse liver. Blood. 1998;91:4600–4607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jooss K, Yang Y, Fisher KJ, Wilson JM. Transduction of dendritic cells by DNA viral vectors directs the immune response to transgene products in muscle fibers. J Virol. 1998;72:4212–4223. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4212-4223.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzynski E, Mingozzi F, Liu YL, Bendo E, Cao O, Wang L, et al. Induction of antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell anergy and deletion by in vivo viral gene transfer. Blood. 2004;104:969–977. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzynski E, Fitzgerald JC, Cao O, Mingozzi F, Wang L, Herzog RW. Prevention of cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to factor IX-expressing hepatocytes by gene transfer-induced regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4592–4597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508685103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino AT, Nayak S, Hoffman BE, Cooper M, Liao G, Markusic DM, et al. Tolerance induction to cytoplasmic β-galactosidase by hepatic AAV gene transfer: implications for antigen presentation and immunotoxicity. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breous E, Somanathan S, Vandenberghe LH, Wilson JM. Hepatic regulatory T cells and Kupffer cells are crucial mediators of systemic T cell tolerance to antigens targeting murine liver. Hepatology. 2009;50:612–621. doi: 10.1002/hep.23043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somanathan S, Breous E, Bell P, Wilson JM. AAV vectors avoid inflammatory signals necessary to render transduced hepatocyte targets for destructive T cells. Mol Ther. 2010;18:977–982. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SW, Hensley SE, Tatsis N, Lasaro MO, Ertl HC. Recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors induce functionally impaired transgene product-specific CD8+ T cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3958–3970. doi: 10.1172/JCI33138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao O, Dobrzynski E, Wang L, Nayak S, Mingle B, Terhorst C, et al. Induction and role of regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells in tolerance to the transgene product following hepatic in vivo gene transfer. Blood. 2007;110:1132–1140. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-073304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Nayak S, Hoffman BE, Terhorst C, Cao O, Herzog RW. Improved induction of immune tolerance to factor IX by hepatic AAV-8 gene transfer. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:767–776. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setiady YY, Coccia JA, Park PU. In vivo depletion of CD4+FOXP3+ Treg cells by the PC61 anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody is mediated by FcγRIII+ phagocytes. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:780–786. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M, Gregori S, Bacchetta R, Roncarolo MG. Tr1 cells: from discovery to their clinical application. Semin Immunol. 2006;18:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Garra A, Vieira P. Regulatory T cells and mechanisms of immune system control. Nat Med. 2004;10:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nm0804-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levings MK, Roncarolo MG. Phenotypic and functional differences between human CD4+CD25+ and type 1 regulatory T cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2005;293:303–326. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27702-1_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Huang CT, Huang X, Pardoll DM. Persistent Toll-like receptor signals are required for reversal of regulatory T cell-mediated CD8 tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:508–515. doi: 10.1038/ni1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mescher MF, Curtsinger JM, Agarwal P, Casey KA, Gerner M, Hammerbeck CD, et al. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Ruiz J, Salaiza-Suazo N, Carrada G, Escoto S, Ruiz-Remigio A, Rosenstein Y, et al. CD8 cells of patients with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis display functional exhaustion: the latter is reversed, in vitro, by TLR2 agonists. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wherry EJ, Ha SJ, Kaech SM, Haining WN, Sarkar S, Kalia V, et al. Molecular signature of CD8+ T cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:670–684. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaiss AK, Liu Q, Bowen GP, Wong NC, Bartlett JS, Muruve DA. Differential activation of innate immune responses by adenovirus and adeno-associated virus vectors. J Virol. 2002;76:4580–4590. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4580-4590.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X, Li J, Samulski RJ. Efficient long-term gene transfer into muscle tissue of immunocompetent mice by adeno-associated virus vector. J Virol. 1996;70:8098–8108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8098-8108.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj AS, Kelly M, Kim D, Chao H. Induction of immune tolerance to FIX by intramuscular AAV gene transfer is independent of the activation status of dendritic cells. Blood. 2010;115:500–509. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Huang X, Yang Y. The TLR9-MyD88 pathway is critical for adaptive immune responses to adeno-associated virus gene therapy vectors in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2388–2398. doi: 10.1172/JCI37607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez VM, Bowen DG, Walker CM. Silencing of T lymphocytes by antigen-driven programmed death in recombinant adeno-associated virus vector-mediated gene therapy. Blood. 2009;113:538–545. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-131375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Zhi Y, Mays L, Wilson JM. Vaccines based on novel adeno-associated virus vectors elicit aberrant CD8+ T-cell responses in mice. J Virol. 2007;81:11840–11849. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01253-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Chirmule N, Gao Gp, Wilson J. CD40 ligand-dependent activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by adeno-associated virus vectors in vivo: role of immature dendritic cells. J Virol. 2000;74:8003–8010. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8003-8010.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Janeway CA Jr. Innate immune recognition and control of adaptive immune responses. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:351–353. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M, Bharadwaj AS, Tacke F, Chao H. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance to coagulation factor IX in the context of intramuscular AAV1 gene transfer. Mol Ther. 2010;18:361–369. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:492–499. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikuma S, Terawaki S, Hayashi T, Nabeshima R, Yoshida T, Shibayama S, et al. PD-1-mediated suppression of IL-2 production induces CD8+ T cell anergy in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;182:6682–6689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac AJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, Sourdive DJ, Suresh M, Altman JD, et al. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2205–2213. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Louboutin JP, Bell P, Greig JA, Li Y, Wu D, et al. Muscle-directed gene therapy for hemophilia B with more efficient and less immunogenic AAV vectors. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:2009–2019. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Calcedo R, Nichols TC, Bellinger DA, Dillow A, Verma IM, et al. Sustained correction of disease in naive and AAV2-pretreated hemophilia B dogs: AAV2/8-mediated, liver-directed gene therapy. Blood. 2005;105:3079–3086. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays LE, Wilson JM. Identification of the murine AAVrh32.33 capsid-specific CD8+ T cell epitopes. J Gene Med. 2009;11:1095–1102. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell P, Limberis M, Gao G, Wu D, Bove MS, Sanmiguel JC, et al. An optimized protocol for detection of E. coli β-galactosidase in lung tissue following gene transfer. Histochem Cell Biol. 2005;124:77–85. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0793-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.