Abstract

Background

Psoriasis (Ps) is a common, relapsing, immune-mediated, inflammatory skin disorder of unknown etiology. Ps is not single organ disease confined to the skin but it is systematic inflammatory condition analogous to other inflammatory immune disorders which are known to have increased risk of heart disease. On other hand, inflammation plays also an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. So, there is striking similarity between molecular and inflammatory pathway in Ps and atherosclerosis.

Aim of the work

Was to assess the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with Ps by using carotid ultrasonography.

Patients and Methods

60 patients with Ps were enrolled in this study after exclusion of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases (CVD). In addition, 20 age and gender matched healthy persons served as controls. Patients were classified according to Ps area and severity index (PASI) score into group I (20 mild patients), group II (20 moderate) and group III (20 severe). The average common carotid artery (CCA) intima media thickness (IMT), internal diameter (ID) and arterial wall mass index (AWMI) were measured using high resolution B- mode ultrasound.

Results

Psoriatic patients showed statistically significant increase in CCA-IMT (P value 0.001), AWMI (P value 0.010) and significant decrease in ID (P value 0.001), as compared to controls.

Conclusion

Psoriasis patients could be suggested as a group with an increased atherosclerotic risk especially in older ages with longer duration of Ps. The carotid IMT, ID and AWMI can identify patients with subclinical atherosclerosis who need special follow up to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Common carotid artery, Intima media thickness, Internal diameter, PASI score

Abbreviations

- Ps

psoriasis

- CVD

cardio-vascular diseases

- PASI

psoriasis area severity index

- CCA

common carotid artery

- IMT

intima media thickness

- ID

internal diameter

- AWMI

arterial wall mass index

- SLE

systemic lupus erythermatosus

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- R

redness

- T

thickness

- S

scalness

- h

head

- u

upper extremities

- t

trunk

- i

lower extremities

- MHz

mega hertz

- GE

general electric

- MI

myocardial Infarction

- BMI

body mass index

Introduction

Psoriasis (Ps) is a common, immune-mediated, inflammatory skin condition of unknown etiology that requires lifelong treatment [1]. Advances in understanding the immunopathogenesis and genetics of Ps have shifted from single organ disease confined to the skin to a systematic inflammatory condition analogous to other inflammatory immune disorders. Patients with immune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or rheumatoid arthritis (RA), are known to have increased risk of heart disease; similarly, patients with Ps carry an excess risk of heart disease [2]. Additionally, inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [3], [4]. There are therefore striking similarities between molecular and inflammatory pathways in psoriasis and atherosclerosis [2].

At present, a number of screening tests that detect symptomatic patients at risk of atherosclerosis are available, such as measurements of carotid artery intima media thickness (IMT) [5] and plaque by high resolution B mode ultrasound. This is a useful, non-invasive surrogate marker of macro vascular atherosclerosis that provides early information on atherosclerosis in subclinical stages of the disease. Increased IMT of the common carotid artery (CCA) is an indicator of generalized atherosclerosis [6]. Carotid atherosclerosis is associated with coronary atherosclerosis and hence the incidence of carotid plaque or increased IMT is higher in patients prone to coronary artery disease [7], [8].

Patients and methods

This study was conducted on 60 psoriatic patients classified according to PASI score into Group I (20 patients with mild psoriasis), Group II (20 patients with moderate psoriasis) and Group III (20 patients with severe psoriasis). The study also included 20 disease-free subjects, with matching age and gender who served as controls. All subjects were recruited from the Outpatient Clinic of Dermatology and Venereology Department, Tanta University Hospital during the period of June 2011 to June 2012. The Research Ethics Committee of the hospital (code No: 870/04/12) approved the study and informed written consent was obtained from each participant.

Exclusion criteria

Patients included in this study did not have other dermatological or systemic diseases considered as risk factors of atherosclerosis such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, SLE or RA. Study patients did not have chronic hepatic or renal diseases, vascular problems (such as CVD) or malignancies. The study excluded psoriasis patients receiving anti-psoriatic drugs, systemic (such as corticosteroid, methotrexate or phototherapy) for at least 6 weeks prior to the date of carotid ultrasonography. Pregnant or lactating women or women on contraceptives were also excluded, as were patients and controls who gave a positive history of smoking.

Study participants were subjected to full history-taking, thorough general and dermatological examinations, routine laboratory investigations that included measurement of blood glucose levels (fasting and 2 h postprandial); measurement of lipid profile (cholesterol, triglycerides, high density lipoprotein and low density lipoprotein); complete blood picture, and hepatic and renal function tests. Participants were then assessed on psoriasis severity using the PASI score, which evaluates the severity of psoriasis in relation to three parameters: erythema (redness) (R), infiltration (thickness) (T) and desquamation (scaliness) (S) [9]. Severity is rated for each index on a 0–4 scale (0 for no involvement, and up to 4 for severe involvement). The body is divided into four regions comprising the head (h), upper extremities (u), trunk (t), and lower extremities (i). In each of these areas, the fraction of total surface area affected is graded on a 0–6 scale (0 for no involvement; up to 6 for greater than 90% involvement). The various body regions are weighed to reflect their respective proportion of body surface area. The composite PASI scores for each region by the weight of area of involvement score for that respective region, and then summing the four resulting quantities; mathematically, this evaluation is as follows: [9].

Measurement of common carotid artery intima media thickness, internal diameter and arterial wall mass index

Carotid IMT was measured as a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis to assess structural changes in the vascular wall using a high resolution B-mode ultrasound with 7.5–10 MHz linear vascular probe (Vivid 7, GE Vingmed Ultrasound).

Patients and controls were examined in supine position with the neck extended and turned slightly to the contralateral side. Both bilateral carotid arteries were scanned in both transverse and longitudinal section to measure the IMT in the far wall of the artery. The best images of the far wall that could be obtained were used to determine the CCA-IMT. Data was built into the machine. CCAs were examined using posterior approach by both transverse and longitudinal scans. Measurements of the CCA-IMT and ID were taken at three points on each side.

-

(1)

CCA (10 mm before the bulb).

-

(2)

Bulb (5–10 mm cranially to the start of the bulb)

-

(3)

Internal carotid artery column after the flow divider.

The IMT was defined as a distance of more than 1.0 mm between the leading edge of the first echogenic line and the leading edge of the second echogenic line. The first line represents the luminal-intimal interface and the second line is produced by the collagen-containing upper layer of the adventitia close to the medial adventitial interface. The maximum IMT, which is the highest IMT value among the six segments studied, were assessed according to sonographic criteria. IMT was considered to be normal if ⩽0.9 mm, while values >0.9 mm were considered to be indicative of thickened intima and value >1.3 mm was indicative of atherosclerotic plaque [10]. The following data were measured:

-

(1)

Internal diameter at the end of diastole.

-

(2)

Intima media thickness at the end of diastole.

-

(3)

Arterial wall mass index (AWMI) was calculated using this equation: [10]

Statistics

All data obtained were transferred to the statistical package for Social Sciences version 15 (IBM Co., New York, USA) for analysis. Data were summarized using mean, standard deviation (mean ± SD) using student’s t test. Comparison between groups was made by using X2 test and Fisher’s Exact Test for quantitative variables. Linear Correlation Coefficient was used for the detection of correlation between two quantitative variables. Statistical significance was determined at a level of p ⩽ 0.05∗; and p ⩽ 0.001∗ was considered highly significant.

Results

Clinical results: the demographic characteristics and disease profile of the patients are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data of studied groups.

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Total | Group IV | f Test | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/year | Range | 19–45 | 28–48 | 26–49 | 19–49 | 22–39 | 2.336 | 0.152 |

| Mean ± SD | 30.4 ± 9.5 | 39.5 ± 6.3 | 38 ± 9.1 | 35.9 ± 5.2 | 30 ± 5.9 | |||

| Gender | Male | 8(40%) | 12(60%) | 12(60%) | 32(53%) | 12(60%) | 3.176 | 0.311 |

| Female | 12(60%) | 8(40%) | 8(40%) | 28(47%) | 8(40%) | |||

| Duration/year | Range | 3–20 | 4–20 | 4–19 | 3–20 | – | 1.345 | 0.632 |

| Mean ± SD | 8.6 ± 2.1 | 10.9 ± 5.1 | 10.6 ± 7.1 | 11.25 ± 6.95 | – | |||

| PASI score | Range | 1.8–9.7 | 10–19 | 21.7–43.6 | 1.8–43.6 | – | 22.36 | 0.001⁎ |

| Mean ± SD | 6 ± 3.2 | 14.3 ± 3.3 | 29.6 ± 6.2 | 18.49 ± 11.29 | – | |||

| Body mass index kg/m2 | Range | 22.5–29.6 | 24.9–29.7 | 25.7–29.9 | 22.5–29.9 | 23.1–28.8 | 1.811 | 0.219 |

| Mean ± SD | 26.5 ± 2.6 | 27.8 ± 1.8 | 27.3 ± 2.8 | 27.3 ± 2.52 | 25.1 ± 3.5 | |||

| Family history | +VE | 10(50%) | 8(40%) | 8(40%) | 26(43.3%) | – | 1.00 | 0.999 |

| -VE | 10(50%) | 12(60%) | 12(60%) | 34(56.7%) | – |

PASI = Ps area and severity index score.

P highly significant ⩽0.001.

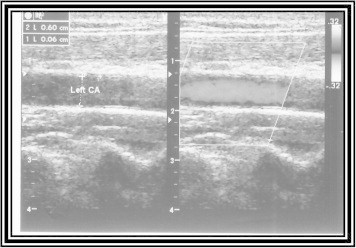

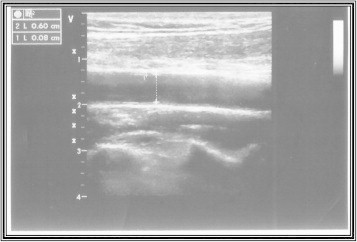

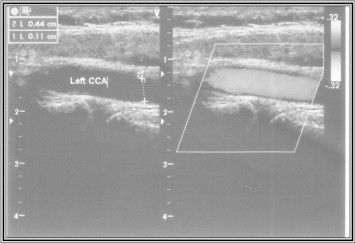

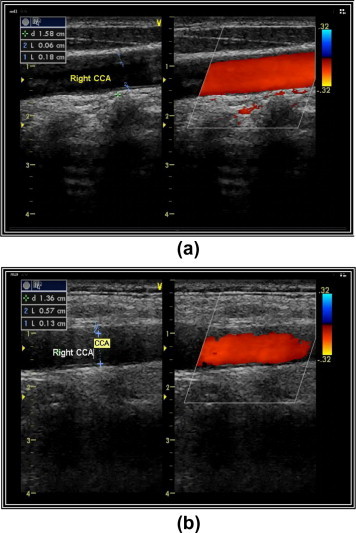

Carotid ultrasonography results are illustrated in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4.

Figure 1.

Carotid artery intima media thickness 0.06 and ID 0.60 cm in control subject. (Values ⩽0.09 mm were considered to be normal).

Figure 2.

Carotid artery intima media thickness 0.08 and ID 0.60 cm in mild psoriatic patient.

Figure 3.

Carotid artery intima media thickness 0.11 and ID 0.44 cm in moderate psoriatic patient.

Figure 4.

(a) Carotid artery intima media thickness 0.13 and ID 0.57 cm in severe psoriatic patient. (b) Carotid artery intima media thickness 0.18 cm (atheromatous plaque in severe psoriatic patient.

As regard the IMT, in Group I; it ranged from 0.036–0.135 cm with the mean (0.07 ± 0.03) cm; in Group II it ranged from 0.045–0.12 cm with the mean (0.09 ± 0.21) cm, while in Group III, it ranged from 0.062–0.141 cm with the mean (0.10 ± 0.02) cm; and in Group IV, it ranged from 0.03–0.079 cm with the mean (0.05 ± 0.01) cm. Comparison between patient groups regarding carotid IMT revealed highly significant difference (P = 0.001). As for the ID, in Group I, it ranged from 0.41–0.79 cm with the mean (0.59 ± 0.09) cm; in Group II, it ranged from 0.41–0.63 cm with the mean (0.51 ± 0.08) while in Group III, it ranged from (0.49–0.60) cm with the mean 0.54 ± 0.05 cm. In Group IV, it ranged from 0.418–0.63 cm with the mean (0.53 ± 0.07) cm.

Comparison between psoriatic patient groups regarding carotid ID revealed a highly significant difference (P = 0.001). As for the AWMI, in Group I, it ranged from 0.077–0.292 mg/cm with the mean (0.14 ± 0.06) mg/cm, while in Group II, it ranged from 0.079–0.199 cm with the mean (0.15 ± 0.03) mg/cm. In Group III, it ranged from 0.112–0.479 mg/cm with the mean (0.23 ± 0.09) mg/cm, and in Group IV, it ranged from 0.047–0.152 mg/cm with the mean (0.09 ± 0.03) mg/cm. A comparison between psoriatic patient groups regarding carotid AWMI revealed a significant difference (P = 0.010) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison between carotid ultrasonography results in the studied groups.

| Group I | Group II | Group III | Total | Group IV | f Test | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMT/cm | Range | 0.036–0.135 | 0.045–0.12 | 0.062–0.14 | 0.036–0.14 | 0.036–0.079 | 11.442 | 0.001⁎ |

| Mean ± SD | 0.07 + 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.21 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | |||

| ID/cm | Range | 0.41–0.79 | 0.41–0.63 | 0.49–0.61 | 0.041–0.79 | 0.418–0.63 | 9.362 | 0.001⁎ |

| Mean ± SD | 0.59 ± 0.09 | 0.0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 0.49 ± 0.18 | 0.53 ± 0.07 | |||

| AWMI(g/cm) | Range | 0.077–0.292 | 0.079–0.199 | 0.112–0.474 | 0.077–0.48 | 0.047–0.152 | 8.963 | 0.010⁎⁎ |

| Mean ± SD | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 0.18 ± 0.08 | 0.09 ± 0.03 |

IMT = Iintima media thickness, ID = Internal diameter, AWMI = Arterial wall mass index.

P highly significant ⩽0.001.

P significant ⩽0.05.

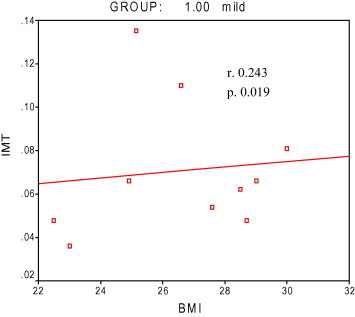

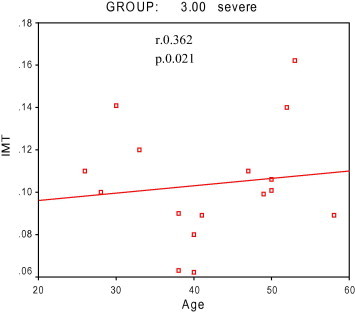

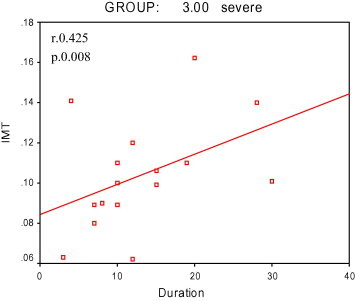

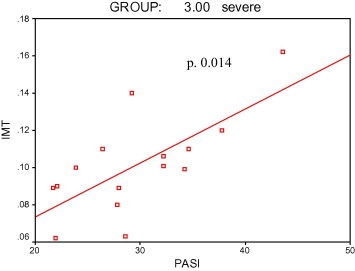

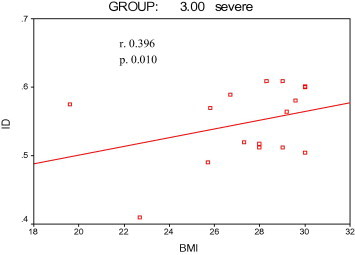

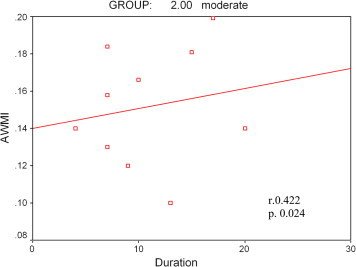

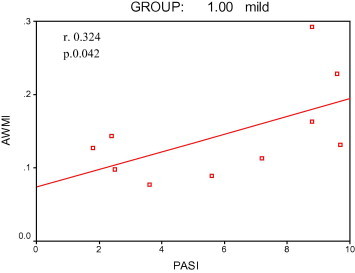

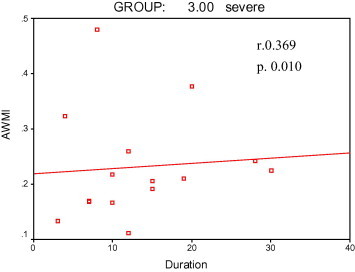

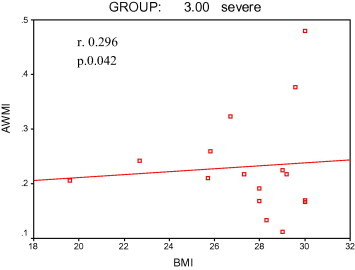

IMT in Group I showed a significant positive correlation with BMI (Fig. 5) while IMT in Group III showed a significant positive correlation with patient ages (Fig. 6), duration of disease (Fig. 7), and PASI score (Fig. 8). The ID in Group III showed significant positive correlation with BMI (Fig. 9) and a significant negative correlation with age of patients and duration of disease. AWMI in Group I showed a positive correlation with duration of disease (Fig. 10) and PASI score (Fig. 11), while in Group III, AWMI showed a significant positive correlation with duration of disease (Fig. 12) and BMI (Fig. 13).

Figure 5.

Intima media thickness in relation to body mass index in Group I. atheromatous.

Figure 6.

Intima media thickness in relation to age in Group III.

Figure 7.

Intima media thickness in relation to duration of disease in Group III.

Figure 8.

Intima media thickness in relation to psoriasis area and severity index in Group III.

Figure 9.

Internal diameter in relation to body mass index in Group III.

Figure 10.

Arterial wall mass index in relation to duration of disease in Group I.

Figure 11.

Arterial wall mass index in relation to psoriasis area and severity index in Group I.

Figure 12.

Arterial wall mass index in relation to duration of disease in Group III.

Figure 13.

Arterial wall mass index in relation to body mass index in Group III.

Discussion

Carotid arteries are of particular interest to investigators because they are easily accessible to non-invasive examination by high resolution B-mode ultrasonography which allows reliable, easily accessible measurement of the carotid artery IMT. The latter is widely used to evaluate premature atherosclerosis in chronic inflammatory diseases such as RA [11] and SLE [12]. The CCA-IMT is an effective sonographic marker of early atherosclerotic changes. It is a good indicator of generalized atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease providing early information on atherosclerosis in the subclinical stages of the disease in individuals at risk [13], [14].

Ultrasonographic data of the current study showed that the mean of IMT in psoriasis groups was (0.07 ± 0.02) cm; and in control group mean IMT was (0.05 ± 0.01) cm. A comparison between psoriasis patients and controls regarding carotid IMT revealed a highly significant difference (P = 0.001). The mean IMT results of the present our controls were similar to Grewal et al., [15] and El-Mongy et al., [16].

The current study confirmed the findings from previous studies that psoriasis was associated with subclinical atherosclerosis by exhibiting an increased carotid-IMT compared with healthy controls [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. Previous studies were performed on chronic psoriasis patients, [16] or on both psoriasis and PsA without other traditional risk factors [22]. The results have shown that psoriasis alone, PsA alone or both had increased CCA-IMT compared with controls. Increased carotid IMT was reported with higher frequency of coronary heart disease in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis than no-psoriasis patients [23]. Moreover, the increased risk of atherosclerosis was further supported by Hahn et al., [24] who found that even after controlling traditional cardiovascular risk factors, psoriasis was conferred as an independent risk for MI. CCA-IMT also serves as a risk factor for MI and stroke in asymptomatic adults, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors [25].

In the present study, the correlation between IMT and age of studied psoriatic patients revealed a significant positive change in Group III. This result was in agreement with that reported by Kimhi et al., [17] Enany et al., [20] and Sahar et al., [22] who showed that IMT correlated with age as a conventional risk factor of atherosclerosis.

The present study revealed there was no significant correlation between IMT and gender of studied psoriatic patients. However, our study revealed a significant positive correlation between IMT and duration of disease in Group III, while no significant correlation was found in Groups I and II. These results were in agreement with various studies [20], [26], [27], [28], [29] which showed that increased cardiovascular risk, manifested as increased carotid IMT, correlates with the duration of the disease, suggesting that long standing inflammation is responsible for subclinical atherosclerosis. These results were in contrast with the study conducted by Sahar et al., [22] who reported no correlation between IMT and duration of disease. Also Balci et al., [19] failed to detect any association between IMT and duration of disease, explaining this failure due to the relatively young (mean age 38.5 years) of their patients.

The current study revealed a significant positive correlation between IMT and BMI in Group I, but not in Groups II and III. These results were in agreement with Kimhi et al. [17] However, Sahar et al. [22] showed no correlation between IMT and BMI. In the this study, there was a significant positive correlation between IMT and PASI score in Group III, while there was no significant correlation in Groups I and II. These results were in line with the study conducted by El-Mongy et al. [16]. Another study concluded that increased disease severity was associated with higher rate of CVD [30]. In contrast, Kimhi et al. [18] and Sahar et al. [23] showed no correlation between IMT and PASI scores. The fact that PASI is not a stable parameter may explain why these authors failed to detect a significant association between subclinical atherosclerosis indicators and PASI scores. The most independent predictor of carotid IMT in the present study was duration of disease (R = 0.425, P = 0.008) followed by age (R = 0.362, P = 0.021), PASI score (R = 0.326, P = 0.014) and BMI (R = 0.243, P = 0.019). These results were in contrast to El-Mongy et al. [16] who demonstrated that age was the most important independent predictor of carotid IMT followed by PASI scores.

There is normal variation in the size of caliber or diameter of carotid arteries from one population to another, therefore ID was not as good an indicator for subclinical atherosclerosis as IMT and AWMI, but its role in this study was to estimate the AWMI by equation, as previously discussed. The mean of ID in psoriasis groups was (0.49 ± 0.18) cm while in the control group it was (0.53 ± 0.07) cm. Comparison between psoriatic patients and the control group regarding carotid ID revealed a highly significant difference.

Regarding the correlation between the ID and clinical data of studied psoriatic patients there was a significant negative correlation between ID and age in Group III but no correlation was found in either Group I or II. There was no correlation between ID and all studied psoriatic groups in relation to gender and PASI score. Also there was a significant negative correlation between ID and duration of disease in Group III, but there was no correlation in either Group I or II. Correlation of ID and BMI revealed a significant positive correlation in Group III.

The AWMI ultrasonographic mean results for all psoriatic groups were (0.18 ± 0.08) g/cm, while in the control group, the mean was (0.09 ± 0.03) g/cm. Comparison between psoriatic patients and controls regarding carotid AWMI revealed a significant difference. Correlation between AWMI in terms of age and gender, revealed no significant correlation in all psoriatic studied groups. Correlation between AWMI and duration of disease showed a statistically significant positive correlation in Group I and III, but there was no significant correlation in Group II. In addition, there was no significant correlation between AWMI and BMI in Groups I and II, while there was a significant positive correlation in Group III. Also there was a significant positive correlation between AWMI and PASI score in Group I, while no significant correlation was found in Groups II and III. The use of AWMI and IMT are effective indicators in the detection of early atherosclerotic changes in the artery, unlike the use of plaque which is a late indicator of atherosclerosis. To our knowledge, no reported previous studies illustrate the association between the ID and AWMI of CCA and the subclinical atherosclerosis in psoriatic patients.

One study showed increased atherosclerosis risk in psoriatic patients, particularly those with moderate/severe disease, as evidenced by increased expression of platelet CD62 compared with healthy controls. Moreover, this study found positive correlation between CD62 expression PASI score [31].

Another study, aimed at assessing the association between psoriasis and cardiovascular outcomes, concluded that psoriatic patients with predominantly mild disease from the general population are as likely to develop atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events as subjects without psoriasis [32].

Finally, in the current study, psoriatic patients showed evidence of subclinical atherosclerosis as indicated by increased carotid IMT and AWMI compared with matched controls. These changes were more pronounced in older patients having more severe disease as indicated by PASI score and longer duration of the disease. All of these results suggest that psoriasis itself is an independent risk factor associated with subclinical atherosclerosis, whereas the presence of coexisting CVD risk factors would aggravate this condition. This leads us to speculate that early onset of atherosclerosis may be a characteristic feature of psoriasis similar to SLE and RA.

Recommendations

Psoriasis patients could be suggested as a group with an increased atherosclerotic risk especially in older ages with more severe psoriasis and longer duration of the disease. Older patients with severe psoriasis therefore need frequent follow-up to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Disclosure: Authors have nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Contributor Information

Raghda Ghonimy Elsheikh, Email: raghdaghonimy@gmail.com.

Tarek El-Sayed Amin, Email: Tarek_ameen4@yahoo.com.

Amal Ahmad El-Ashmawy, Email: elashmawy2013@yahoo.com.

Samah Ibrahim Abd El-fttah Abdalla, Email: Samahi@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Griffiths C.E., Barker J.N. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370(9583):263–271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61128-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kremers H.M., McEvoy M.T., Dann F.J., Gabriel S.E. Heart disease in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2):347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson D., Jr., Hackett M., Wong J., Kimball A.B., Cohen R., Bala M. IMID Study Group. Co-occurrence and comorbidities in patient with immune-mediated inflammatory disorders: an exploration using US health care claims data, 2001–2002. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(5):989–1000. doi: 10.1185/030079906X104641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansson G.K., Libby P. The immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(7):508–519. doi: 10.1038/nri1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naghavi M., Falk E., Hecht H.S., Jamieson M.J., Kaul S., Berman D. From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable patient–Part III: executive summary of the screening for heart attack prevention and education (SHAPE) task force report. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(2A):2H–15H. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimball A.B., Gladman D., Gelfand J.M., Gordon K., Horn E.J., Korman N.J. National psoriasis foundation clinical consensus on psoriasis comorbidities and recommendations for screening. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(6):1031–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gottlieb A.B., Chao C., Dann F. Psoriasis comorbidities. J Dermatol Treat. 2008;19(1):5–21. doi: 10.1080/09546630701364768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celermajer D.S., Sorensen K.E., Gooch V.M., Spiegelhalter D.J., Miller O.I., Sullivan I.D. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet. 1992;340(8828):1111–1115. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93147-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van de Kerkhof P.C. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index and alternative approaches for the assessment of severity: persisting areas of confusion. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(4):661–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fathi R., Marwick T.H. Noninvasive tests of vascular function and structure: why and how to perform them. Am Heart J. 2001;141(5):694–703. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kassem E., Ghonimy R., Adel M., El-Sharnoby G. Non traditional risk factors of carotid atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Egypt Rheumatol. 2011;33(3):113–119. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roman M.J., Shanker B.A., Davis A., Lockshin M.D., Sammaritano L., Simantov R. Prevalence and correlates of accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematous. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(25):2399–2406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simons S., Algra A., Bots M.L., Grobbee D., Van der Graaf Y. Common carotid intima-media thickness and arterial stiffness: indicators of cardiovascular risk in high-risk patients. The SMART Study (Second Manifestation of ARTerial Disease) Circulation. 1999;100(9):951–957. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.9.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Copeland R., Birrell F., Worselet A. Psoriatic arthritis treatment approach. Hosp Pharm. 2008;15:207–211. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerwal J., Anand S., Islam S., Lonn E. SHARE and SHARE-AP Investigators. Prevalence and predictors of subclinical atherosclerosis among asymptomatic “low risk” individuals in a multiethnic population. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197(1):435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Mongy S., Fathy H., Abdelaziz A., Omran E., George S., Neseem N. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimhi O., Caspi D., Bornstein N.M., Maharshak N., Gur A., Arbel Y. Prevalance and risk factors of atherosclerosis in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36(4):203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tam L.S., Shang Q., Li E.K., Tomlinson B., Chu T.T., Li M. Subclinical carotid atherosclerosis in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1322–1331. doi: 10.1002/art.24014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balci D.D., Balci A., Karazincir S., Ucar E., Iyigun U., Yalcin F. Increased carotid artery intima-media thickness and impaired endothelial function in psoriasis. J Eurn Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enany B., El Zohiery A.K., Elhilaly R., Badr T. Carotid intima-media thickness and serum leptin in psoriasis. Herz. 2012;37(5):527–533. doi: 10.1007/s00059-011-3547-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez-Juanatey C., Llorca J., Miranda-Filloy J.A., Amigo-Díaz E., Testa A., García-Porrúa C. Endothelial dysfunction in psoriatic arthritis patients without clinically evident cardiovascular disease or classic atherosclerosis risk factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(2):287–293. doi: 10.1002/art.22530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sahar S., Shereen H., Iman B., Amer Y. Susceptibility to atherosclerosis in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis as determined by increased carotid artery intima-media thickness. Egypt J Dermatol Androl. 2009;20:159–172. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sommer D.M., Jenisch S., Suchan M., Christophers E., Weichenthal M. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;298(7):321–328. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0703-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hahn B.H., Grossman J., Chen W., McMahon M. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis in autoimmune rheumatic diseases: roles of inflammation and dyslipidemia. J Autoimmun. 2007;28(2–3):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Leary D.H., Polak J.F., Kronmal R.A., Manolio T.A., Burke G.L., Wolfson S.K., Jr. Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(1):14–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gelfand J.M., Neimann A.L., Shin D.B., Wang X., Margolis D.J., Troxel A.B. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296(14):1735–1741. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.14.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakkee M., Thio H.B., Prens E.P., Sijbrands E.J., Neumann H.A. Unfavorable cardiovascular risk profiles in untreated and treated psoriasis patients. Atherosclerosis. 2007;190(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soy M., Yildiz M., Sevki Uyanik M., Karaca N., Güfer G., Piskin S. Susceptibility to atherosclerosis in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis as determined by carotid-femoral (aortic) pulse-wave velocity measurement. Article in Spanish. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62(1):96–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eder L., Zisman D., Barzilai M., Laor A., Rahat M., Rozenbaum M. Subclinical atherosclerosis in psoriatic arthritis: a case-control study. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(5):877–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25(6):529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saleh HM., Attia EA., Onsy AM., Saad AA., Abd Ellah MM. Platelet activation: a link between psoriasis per se and subclinical atherosclerosis–a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(1):68–75. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dowlatshahi E.A., Kavousi M., Nijsten T., Ikram M.A., Hofman A., Franco O.H. Psoriasis is not associated with atherosclerosis and incident cardiovascular events: the Rotterdam study. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(10):2347–2354. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]