Abstract

Genomic imprinting is a normal process of epigenetic regulation leading some autosomal genes to be expressed from one parental allele only, the other parental allele being silenced. The reasons why this mechanism has been selected throughout evolution are not clear; however, expression dosage is critical for imprinted genes. There is a paradox between the fact that genomic imprinting is a robust mechanism controlling the expression of specific genes and the fact that this mechanism is based on epigenetic regulation that, per se, should present some flexibility. The robustness has been well studied, revealing the epigenetic modifications at the imprinted locus, but the flexibility has been poorly investigated.

Prader-Willi syndrome is the best-studied disease involving imprinted genes caused by the absence of expression of paternally inherited alleles of genes located in the human 15q11-q13 region. Until now, the silencing of the maternally inherited alleles was like a dogma. Rieusset et al. showed that in absence of the paternal Ndn allele, in Ndn +m/-p mice, the maternal Ndn allele is expressed at an extremely low level with a high degree of non-genetic heterogeneity. In about 50% of these mutant mice, this stochastic expression reduces birth lethality and severity of the breathing deficiency, correlated with a reduction in the loss of serotonergic neurons. Furthermore, using several mouse models, they reveal a competition between non-imprinted Ndn promoters, which results in monoallelic (paternal or maternal) Ndn expression, suggesting that Ndn monoallelic expression occurs in the absence of imprinting regulation. Importantly, specific expression of the maternal NDN allele is also detected in post-mortem brain samples of PWS individuals. Here, similar expression of the Magel2 maternal allele is reported in Magel2 +m/-p mice, suggesting that this loss of imprinting can be extended to other PWS genes. These data reveal an unexpected epigenetic flexibility of PWS imprinted genes that could be exploited to reactivate the functional but dormant maternal alleles in PWS.

Keywords: imprinting, Prader-Willi, Necdin, Magel2, mouse model

Genomic imprinting is a normal process of gene regulation revealed in mammals1 and flowering plants.2 Genomic imprinting leads some autosomal genes to be expressed solely from the maternal inherited chromosomes, and others are expressed solely from the paternal inherited chromosomes; thus, the corresponding paternally or maternally inherited alleles, respectively, are silenced. It is a non-Mendelian epigenetic form of gene regulation that is germline-inherited, the epigenetic marks being established in the parental gametes without altering the DNA sequence. The marks are subsequently maintained after fertilization, transmitted through cell division and differentiation and read in the tissue where the parental allele should be repressed.1

Approximately 150 genes are imprinted in mouse and in humans (www.har.mrc.ac.uk/research/genomic-imprinting/), and the vast majority are expressed in placenta and in the brain. At the individual level, a monoallelic expression instead of a biallelic expression should be more deleterious since, when mutated, the functioning allele could not be compensated by the other allele that is silenced; this raises the question about the relevance of genomic imprinting. The reason(s) why this mechanism has been selected/maintained throughout evolution is not clear, although several hypotheses have been put forward.3 Obviously, genomic imprinting imposes sexual reproduction since the functional contributions of the paternal and maternal genomes are necessary for normal embryonic and extra-embryonic development.4-6 Post-natally, imprinted genes are mainly involved in metabolism,7,8 energy homeostasis, and behavior9 and play a role in the adaptation to early postnatal life.10 A lack of expression of some of these genes is associated with pathologies in human and mouse, and a 2-fold increase in imprinted gene expression can also be found in human disorders, suggesting that expression dosage is critical for at least some imprinted genes.11 In view of this, genomic imprinting should be a robust mechanism, reproducible from generation to generation and allowing (1) the monoallelic expression of those paternal or maternal developmental genes necessary for a normal development and (2) a control over gene dosage to prevent both copies being expressed.

Paradoxically to this idea of robustness, imprinting regulation is an epigenetic mechanism, and per se, flexibility of this mechanism should be observed in somatic cells. Indeed, imprinted genes have been hypothesized to be vulnerable to environmental perturbation,12,13 leading to somatic imprinting alterations and causing several developmental diseases.14 It has also been suggested that genomic imprinting allows developmental plasticity in response to environmental conditions.15 However in a situation of induced maternal undernutrition, an environmental alteration, imprinted genes appear neither more susceptible to, or more protected from, expression perturbations, either in the F1 or F2 generation.8 An interesting approach to study the flexibility of genomic imprinting might be analysis of genes showing tissue specific imprints (approximately 30% of all imprinted genes). The aforementioned genes show imprinted expression in one specific tissue and biallelic expression in other tissues within the same organism, suggesting that tissue-specific factors contribute to the allelic relaxation.16 The study of these tissue-specific differences in allelic expression will shed new light on the relationship between epigenetic marks and the state of allelic repression.

When the active allele of an imprinted gene is mutated, loss of imprinting (LOI) might compensate for the lack of expression of this gene, allowing the expression of the corresponding silent allele. In this context, such an imprinted flexibility might be considered as a rheostat that enhances the adaptability to a changing genomic environment and might potentially contribute to the positive selection of imprinting mechanisms through mammalian evolution. Until now, few cases of reactivation of a normally silent allele rescuing an altered phenotype have been described,17,18 but it seems important to examine other situations in which the LOI improves and/or rescues a phenotypic trait. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the robustness and/or flexibility of imprinting regulation is an important first step in finding ways to manipulate this rheostat function in health and disease.

Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) is the most studied neurogenetic disease involving imprinted genes (1/25000, OMIM 176270). The essential clinical criteria include neonatal hypotonia and abnormal feeding behavior with a poor suck followed by a hyperphagia, resulting in severe obesity and behavioral problems.19-22 Breathing deficiency, with central apneas present from birth, is a significant health concern for many patients and contributes to some cases of sudden death.23,24 Other characteristics of the syndrome include hypogonadism, severe skin picking, and abnormal pain responses. Notably, there is considerable variability in the severity of the symptoms among patients.19 To date, no comprehensive physiopathological mechanisms have been clearly identified. A dysfunction of the central nervous system, in particular of the hypothalamus, has been identified in PW patients and mouse models for PWS share this dysfunction.25

From the genetic point of view, PWS is a contiguous gene syndrome resulting from the loss of expression of the paternal copies of genes located in the 15q11-q13 region; thus, PWS involves a cluster of maternally imprinted genes19—five genes code for proteins (MKRN3, MAGEL2, NECDIN, NPAP1/C15orf12, and SNURF-SNRPN), other genes code for large non-coding transcripts and orphan snoRNAS, including SNORD116. Until now, based on genomic data, a major role was suggested for the SNORD116 snoRNAs, although the role of these snoRNAs was largely debated, and recently, an important role has been attributed to the large non-coding host transcript encoding the SNORD116.26 Very recently, pathogenic mutations of MAGEL2 have been reported in four patients,27 causing a classical PWS in one patient and PWS-like phenotypes in the three others; all patients presented feeding difficulties in infancy, ASD, and intellectual disability. These results underline the major role of MAGEL2 in PWS. The high degree of conservation of the PWS imprinted cluster between mouse and human at the level of both genomic organization and imprinting status has allowed the use of mouse models. Models have been established where all the paternally expressed genes in the cluster have been inactivated, but their physiological analysis has been limited since 80% of the mutant neonates die.28-31 Their death results from a failure to thrive reminiscent of the early problems encountered in the PWS phenotype. Recently, by modifying the genetic background, a higher degree of survival has been obtained, and the resulting adult animals recall some PW features.32 Single gene knockouts have also been created in order to link a specific gene with specific aspects of the PWS phenotype,25 and based on the results from different laboratories, the mouse models in which Magel2 or Necdin have been inactivated, recapitulate many PW features.

Since the first human and mouse PWS candidate genes33,34 were discovered, it has been widely accepted that only their paternal alleles are expressed, the maternal alleles being completely silenced. Consequently, all the studies of mouse models have been done using heterozygous animals deleted for the paternal allele.25

However, it should be noted that the lack of maternal expression of the PW candidate genes in humans is mainly based on the absence of their corresponding transcripts in lymphoblasts, fibroblasts, and, only in a few cases, human brain tissues of PW patients (while the exact origin of the brain structure is not known). The methods used were classical reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction or Northern blot analysis. A relaxation of imprinting in two PW patients with a deletion and two atypical PW patients with a maternal disomy have been reported;35,36 however, both studies were again made on RNAs from patients’ lymphoblasts, and these studies have not been followed up. In particular, no study has ever been done using RT-qPCR or in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry in the brains of PW patients, in whom the maternal alleles are always present. Similarly, studies performed in mouse models of PWS, in which the whole paternal region is deleted or inactivated as in PW patients, initially reported a lack of expression of the maternally inherited genes.29 Subsequently, using real quantitative PCR, an incomplete silencing of PWS genes in brains of one of the mouse models has been reported;28 the other models have not been investigated concerning this question.

In a recent publication in Plos Genetics,18 Rieusset et al. reported that the mechanism regulation imprinting at the PWS locus might be flexible in both a mouse model with an inactivated Necdin (Ndn) gene and in PW patients. The Ndn gene is responsible for the respiratory distress observed in Ndn deficient mice37,38 and probably in PW patients.

This study reports a stochastic expression of the maternally inherited allele of the Ndn gene in mice where the paternal gene (Ndn +m/-p mice) has been inactivated. Quantification of maternal Ndn transcripts using RT-qPCR showed an extremely low and very variable number of transcripts that were not detectable by classical RT-PCR. Unexpectedly, immunohistochemistry using anti-Ndn antibodies confirmed that these transcripts are translated into Necdin protein, detected in around 50% of Ndn +m/-p mice. In contrast, no expression of the maternal allele was detected in wild-type mice suggesting that it is the absence of the paternal allele that is a prerequisite for maternal allele expression. Furthermore a comparison between Ndn −/− and Ndn +m/-p pups showed that the lethality, due to respiratory distress, is decreased 2-fold in Ndn +m/-p compared with Ndn −/−. In agreement with this decreased lethality, the surviving Ndn +m/-p mice present a greater than 2-fold decreased incidence of apnea in adulthood. Since these apneas in Ndn deficient mice have previously been correlated with a deficit in the 5HT system,37 the authors searched for a correlation between the number of 5HT neurons and the number of 5HT neurons expressing Necdin in Ndn +m/-p mice. Indeed, at the cellular level, a positive correlation was established between the level of Necdin expression and the number of 5HT neurons. This confirms the functional importance of the extremely weak expression of the Ndn maternal allele. Finally, NDN transcripts and protein were also detected in brain tissue from human Prader-Willi patients suggesting a relaxation of imprinting.

The results presented in this article nevertheless provoke a number of key questions.

(1) What is the mechanism allowing such maternal expression?

Rieusset et al. proposed that expression of the maternally inherited allele occurs only in absence of an active paternal allele. In support of this hypothesis, they showed that the expression of a non-imprinted BAC transgene, with the Ndn promoter driving eGFP expression, is significantly higher in Ndn−/− and Ndn+m/-p mice compared with WT offspring, and eGFP expression is absent in a mouse model overexpressing Ndn. Furthermore, on a wild-type genetic background, either eGFP or Necdin but not both, is expressed in the cells of the same brain structure that should normally express Necdin, suggesting a mechanism of expression resulting from an allelic exclusion. Explanations for these observations might include promoter competition for transcriptional activators or a mechanism involving physical contact in trans between promoters, a type of counting mechanism described in X chromosome inactivation.39 It has previously been reported that there is pairing between the imprinted region of 15q11-q13 in humans, but this has not yet been confirmed in the mouse syntenic region.40 Recently, it has been shown that chromosome pairing in somatic cells, including imprinted regions, is associated with trans-allelic effects on gene transcription.41 Altogether, these results suggest that, even in the absence of imprinting regulation of Ndn as is the case for the Ndn-eGFP BAC transgene, it appears that there is a transcriptional regulation predisposed to a monoallelic expression of Ndn. In this context of allelic exclusion, an imprinting mechanism dictates that the maternal allele is inactivated. Imprinted genes are functionally monoallelic in a parent of origin-specific manner. This is the first data indicating that gene dosage and parent-origin expression of the Ndn imprinted gene might be dissociated.

Inter- and intra-individual variation in DNA methylation at the DMRs of imprinted genes has been reported in different tissues, most importantly in the brain, and might be a source of imprinting relaxation and phenotypic variations.42 In the article, the authors studied DNA methylation in a secondary DMR (42 CpGs), previously shown to be correlated with imprinted regulation of Ndn expression, although methylation of this DMR occurs after the blastula stage. The sodium bisulphite sequencing study did not however reveal any major changes in methylation on the Ndn maternal allele in Ndn +m/-p brains. This failure to detect modifications to methylation in a secondary DMR may be the result of using whole brain extracts in the analysis: only a few neurons express the Ndn maternal allele, and this escapes the global brain analysis that was performed. However, another explanation might be that the methylation profile does not change, but histone modifications allow an expression of the silent maternally inherited allele.

In the context of cellular mechanism, an important question is: does the expression from the maternal allele result from all-or-none loss of imprinting in mRNA expression in single cells as described for the PLAGL1 gene?43 The all-or-none loss of imprinting of Ndn at the single cell level has not been demonstrated, although this model is supported by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization results where a restricted number of cells express the maternal allele. It would be interesting to explore this all-or-none relaxation using RT-qPCR in single cells, but this is a technically difficult experiment since we cannot identify, a priori, which cells express the Ndn maternal allele.

(2) Can this relaxation of imprinting be generalized to other PWS genes?

In the literature, using RT-qPCR, an incomplete silencing of PWS genes in brains of one of the mouse models with an imprinting mutation has been previously reported.28 The maternal expression could only be detected in the absence of a functional PWS-imprinting center and is suggested to be due to a trans effect on the maternal allele.

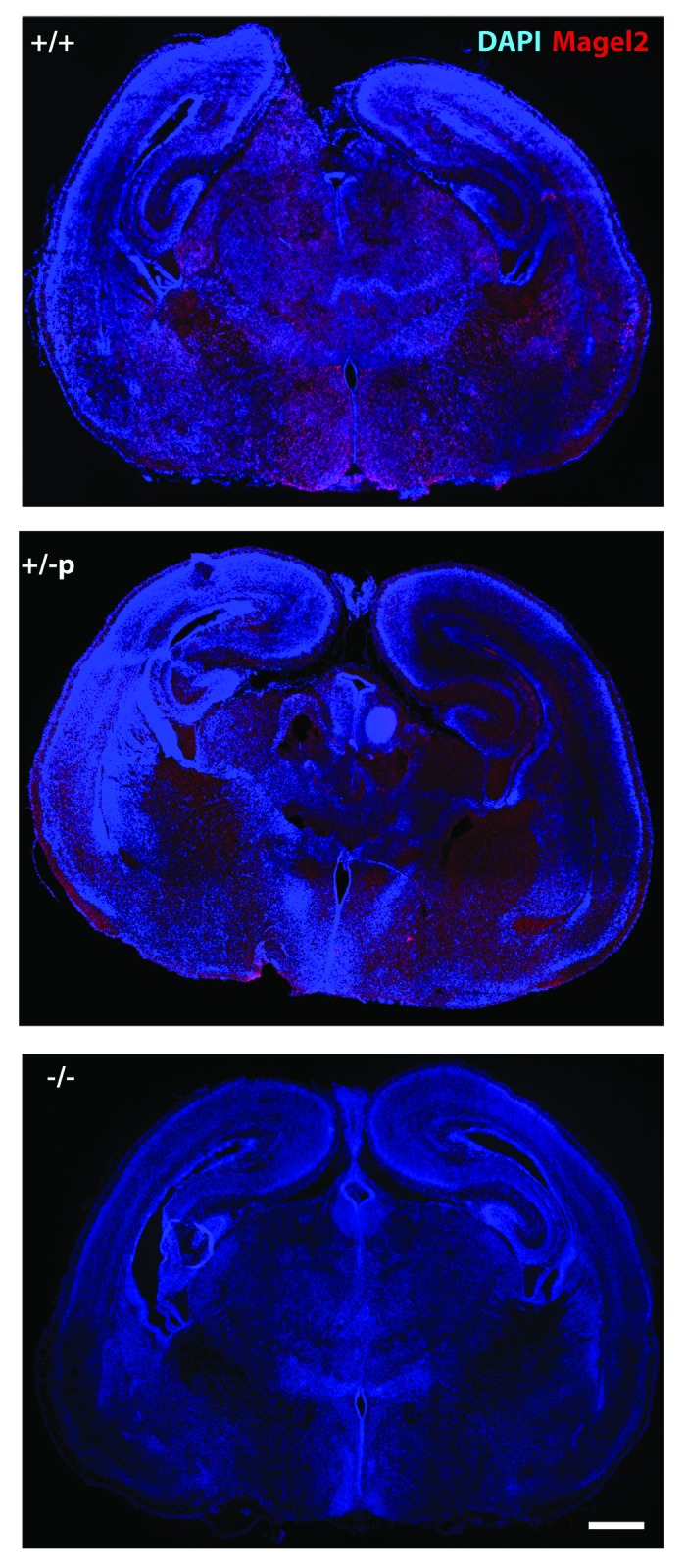

Our team has also investigated a mouse model deleted for the paternal allele of Magel2, another imprinted candidate gene for PWS. The mouse model presents a deletion including the Magel2 promoter, and consistent with the results obtained for Ndn, we detected Magel2 transcripts by ISH in Magel2+m/-p mice as shown in Figure 1. Unfortunately, we do not have a specific anti-Magel2 antibody, and we cannot check the presence of the Magel2 protein. Importantly, the presence of Magel2 transcripts has also been observed on brain sections from PW patients (data not shown).

Figure 1. Detection of Magel2 transcript on brain sections of Magel2 +m/-p mice. Using a specific anti-sense probe for Magel2 transcript44 (in red), in situ hybridization was performed on coronal brain sections issued from Magel2 +/+, Magel2 +m/-p, and Magel2 −/− newborns (P0). Although no signal was detected on brain sections from Magel2 −/− mice, an expected signal is detected in wild type mice and also in Magel2 +m/-p mice. Scale bar: 500 µm.

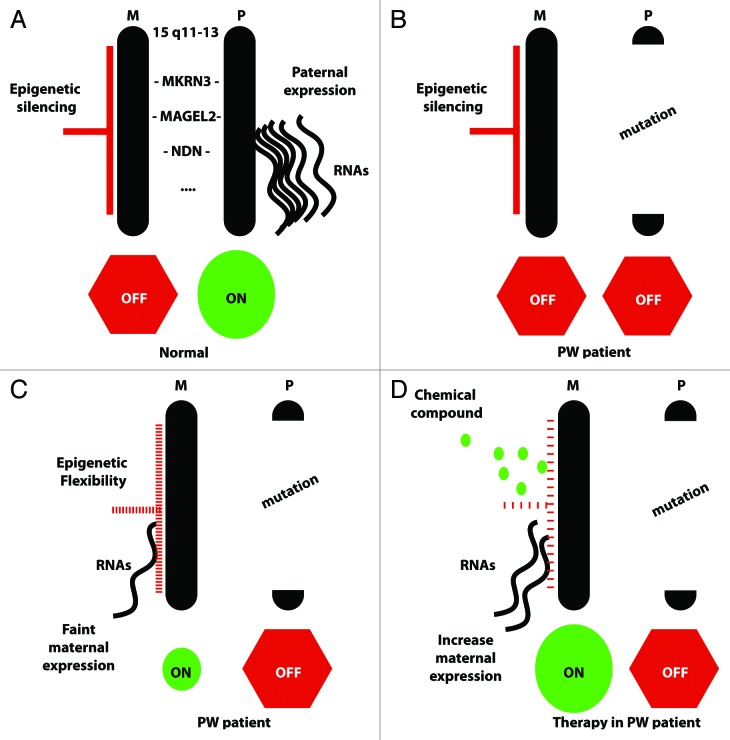

Altogether, these data suggest that the maternally inherited alleles of PWS genes might be reactivated in pathological conditions, in absence of a fully active paternal allele. Importantly, Rieusset et al. revealed that very low levels of expression of PWS maternally silenced genes might be sufficient to alleviate or rescue specific PWS symptoms and might explain the high variability in the severity of the symptoms observed in PW patients. These results are important in a therapeutic perspective, and an understanding of the context in which the Ndn maternal allele might be transcribed could be an important step toward the development of a pharmacological therapy to trigger and/or increase the expression of this maternal allele in PWS patients (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. From a controlled epigenetic silencing to loss of silencing and reactivation of the maternal alleles of PWS genes. This scheme summarizes the quantity of transcripts produced from the maternal and paternal inherited alleles of PWS genes such as NECDIN (NDN) and MAGEL2 in a normal individual (A), in PW patients (B and C), or in perspective of a pharmacological therapy (D). In a normal individual, chromosomal 15q11-q13 regions from both parental origins are present, and transcripts issued only from the paternal allele of PWS genes are detected (A). In PW patients, due to a mutation of the 15q11-q13 region, there are no “PWS transcripts” issued from the paternal active allele (B, C, and D). However, a stochastic partial loss of silencing of the maternal alleles, named here epigenetic flexibility, may result in the production of few maternal “PWS transcripts” detected in some patients (C). We postulate that chemical compounds might modify this epigenetic flexibility in PW patients, allowing an increased expression of the maternal “PWS transcripts” and consequently alleviating the PWS features (D).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

Studies in the authors’ laboratory were funded by INSERM (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale), by ANR (Agence Nationale de la Recherche) grant PRAGEDER, by European community (grant #512136 PWS), and by Fondation Jerôme LeJeune. We acknowledge Pr Keith Dudley for his helpful comments.

References

- 1.Reik W, Walter J. Genomic imprinting: parental influence on the genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:21–32. doi: 10.1038/35047554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gehring M. Genomic Imprinting: Parental Lessons from Plants. Annu Rev Genet. 2013 doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood AJ, Oakey RJ. Genomic imprinting in mammals: emerging themes and established theories. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton SC, Surani MA, Norris ML. Role of paternal and maternal genomes in mouse development. Nature. 1984;311:374–6. doi: 10.1038/311374a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGrath J, Solter D. Completion of mouse embryogenesis requires both the maternal and paternal genomes. Cell. 1984;37:179–83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90313-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Surani MA, Barton SC, Norris ML. Development of reconstituted mouse eggs suggests imprinting of the genome during gametogenesis. Nature. 1984;308:548–50. doi: 10.1038/308548a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith FM, Garfield AS, Ward A. Regulation of growth and metabolism by imprinted genes. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;113:279–91. doi: 10.1159/000090843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radford EJ, Isganaitis E, Jimenez-Chillaron J, Schroeder J, Molla M, Andrews S, Didier N, Charalambous M, McEwen K, Marazzi G, et al. An unbiased assessment of the role of imprinted genes in an intergenerational model of developmental programming. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies W, Isles AR, Humby T, Wilkinson LS. What are imprinted genes doing in the brain? Epigenetics. 2007;2:201–6. doi: 10.4161/epi.2.4.5379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charalambous M, Ferron SR, da Rocha ST, Murray AJ, Rowland T, Ito M, Schuster-Gossler K, Hernandez A, Ferguson-Smith AC. Imprinted gene dosage is critical for the transition to independent life. Cell Metab. 2012;15:209–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNamara GI, Isles AR. Dosage-sensitivity of imprinted genes expressed in the brain: 15q11-q13 and neuropsychiatric illness. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:721–6. doi: 10.1042/BST20130008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann MR, Lee SS, Doherty AS, Verona RI, Nolen LD, Schultz RM, Bartolomei MS. Selective loss of imprinting in the placenta following preimplantation development in culture. Development. 2004;131:3727–35. doi: 10.1242/dev.01241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jirtle RL, Skinner MK. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:253–62. doi: 10.1038/nrg2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim AL, Ferguson-Smith AC. Genomic imprinting effects in a compromised in utero environment: implications for a healthy pregnancy. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:201–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radford EJ, Ferrón SR, Ferguson-Smith AC. Genomic imprinting as an adaptative model of developmental plasticity. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2059–66. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prickett AR, Oakey RJ. A survey of tissue-specific genomic imprinting in mammals. Mol Genet Genomics. 2012;287:621–30. doi: 10.1007/s00438-012-0708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ineson J, Stayner C, Hazlett J, Slobbe L, Robson E, Legge M, Eccles MR. Somatic reactivation of expression of the silent maternal Mest allele and acquisition of normal reproductive behaviour in a colony of Peg1/Mest mutant mice. J Reprod Dev. 2012;58:490–500. doi: 10.1262/jrd.11-115A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieusset A, Schaller F, Unmehopa U, Matarazzo V, Watrin F, Linke M, Georges B, Bischof J, Dijkstra F, Bloemsma M, et al. Stochastic loss of silencing of the imprinted Ndn/NDN allele, in a mouse model and humans with prader-willi syndrome, has functional consequences. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, Driscoll DJ. Prader-Willi syndrome. Genet Med. 2012;14:10–26. doi: 10.1038/gim.0b013e31822bead0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler MG. Prader-Willi Syndrome: Obesity due to Genomic Imprinting. Curr Genomics. 2011;12:204–15. doi: 10.2174/138920211795677877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McAllister CJ, Whittington JE, Holland AJ. Development of the eating behaviour in Prader-Willi Syndrome: advances in our understanding. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:188–97. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dykens EM, Lee E, Roof E. Prader-Willi syndrome and autism spectrum disorders: an evolving story. J Neurodev Disord. 2011;3:225–37. doi: 10.1007/s11689-011-9092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Festen DA, de Weerd AW, van den Bossche RA, Joosten K, Hoeve H, Hokken-Koelega AC. Sleep-related breathing disorders in prepubertal children with Prader-Willi syndrome and effects of growth hormone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4911–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tauber M, Diene G, Molinas C, Hébert M. Review of 64 cases of death in children with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146:881–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Resnick JL, Nicholls RD, Wevrick R. Recommendations for the investigation of animal models of Prader-Willi syndrome. Mamm Genome. 2013;24:165–78. doi: 10.1007/s00335-013-9454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Powell WT, Coulson RL, Crary FK, Wong SS, Ach RA, Tsang P, Alice Yamada N, Yasui DH, Lasalle JM. A Prader-Willi locus lncRNA cloud modulates diurnal genes and energy expenditure. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4318–28. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaaf CP, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Xia F, Potocki L, Gripp KW, Zhang B, Peters BA, McElwain MA, Drmanac R, Beaudet AL, et al. Truncating mutations of MAGEL2 cause Prader-Willi phenotypes and autism. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1405–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chamberlain SJ, Johnstone KA, DuBose AJ, Simon TA, Bartolomei MS, Resnick JL, Brannan CI. Evidence for genetic modifiers of postnatal lethality in PWS-IC deletion mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2971–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang T, Adamson TE, Resnick JL, Leff S, Wevrick R, Francke U, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Brannan CI. A mouse model for Prader-Willi syndrome imprinting-centre mutations. Nat Genet. 1998;19:25–31. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabriel JM, Merchant M, Ohta T, Ji Y, Caldwell RG, Ramsey MJ, Tucker JD, Longnecker R, Nicholls RD. A transgene insertion creating a heritable chromosome deletion mouse model of Prader-Willi and angelman syndromes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9258–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9258. [In Process Citation] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dubose AJ, Smith EY, Yang TP, Johnstone KA, Resnick JL. A new deletion refines the boundaries of the murine Prader-Willi syndrome imprinting center. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3461–6. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Relkovic D, Doe CM, Humby T, Johnstone KA, Resnick JL, Holland AJ, Hagan JJ, Wilkinson LS, Isles AR. Behavioural and cognitive abnormalities in an imprinting centre deletion mouse model for Prader-Willi syndrome. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:156–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glenn CC, Porter KA, Jong MT, Nicholls RD, Driscoll DJ. Functional imprinting and epigenetic modification of the human SNRPN gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:2001–5. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.12.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cattanach BM, Barr JA, Evans EP, Burtenshaw M, Beechey CV, Leff SE, Brannan CI, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Jones J. A candidate mouse model for Prader-Willi syndrome which shows an absence of Snrpn expression. Nat Genet. 1992;2:270–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1292-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogan PK, Seip JR, White LM, Wenger SL, Steele MW, Sperling MA, Menon R, Knoll JH. Relaxation of imprinting in Prader-Willi syndrome. Hum Genet. 1998;103:694–701. doi: 10.1007/s004390050893. [In Process Citation] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muralidhar B, Marney A, Butler MG. Analysis of imprinted genes in subjects with Prader-Willi syndrome and chromosome 15 abnormalities. Genet Med. 1999;1:141–5. doi: 10.1097/00125817-199905000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zanella S, Watrin F, Mebarek S, Marly F, Roussel M, Gire C, Diene G, Tauber M, Muscatelli F, Hilaire G. Necdin plays a role in the serotonergic modulation of the mouse respiratory network: implication for Prader-Willi syndrome. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1745–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4334-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren J, Lee S, Pagliardini S, Gérard M, Stewart CL, Greer JJ, Wevrick R. Absence of Ndn, encoding the Prader-Willi syndrome-deleted gene necdin, results in congenital deficiency of central respiratory drive in neonatal mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1569–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01569.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu N, Tsai CL, Lee JT. Transient homologous chromosome pairing marks the onset of X inactivation. Science. 2006;311:1149–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1122984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thatcher KN, Peddada S, Yasui DH, Lasalle JM. Homologous pairing of 15q11-13 imprinted domains in brain is developmentally regulated but deficient in Rett and autism samples. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:785–97. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krueger C, King MR, Krueger F, Branco MR, Osborne CS, Niakan KK, Higgins MJ, Reik W. Pairing of homologous regions in the mouse genome is associated with transcription but not imprinting status. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider E, Pliushch G, El Hajj N, Galetzka D, Puhl A, Schorsch M, Frauenknecht K, Riepert T, Tresch A, Müller AM, et al. Spatial, temporal and interindividual epigenetic variation of functionally important DNA methylation patterns. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:3880–90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diplas AI, Hu J, Lee MJ, Ma YY, Lee YL, Lambertini L, Chen J, Wetmur JG. Demonstration of all-or-none loss of imprinting in mRNA expression in single cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:7039–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaller F, Watrin F, Sturny R, Massacrier A, Szepetowski P, Muscatelli F. A single postnatal injection of oxytocin rescues the lethal feeding behaviour in mouse newborns deficient for the imprinted Magel2 gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4895–905. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]