To the Editor

Left anterior fascicular block (LAFB) is considered a benign electrocardiographic (ECG) finding,1 but its long-term consequences have not been comprehensively studied. Conduction blocks occur due to conduction system fibrosis and are associated with myocardial fibrosis, even in the absence of other cardiovascular disease.2,3 Therefore, LAFB may be an immediately accessible marker of left heart fibrosis, a substrate for atrial fibrillation (AF)4 and congestive heart failure (CHF).5 We investigated the long-term outcomes of participants with LAFB in the absence of manifest cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS).

Methods

Established in 1989, CHS is a prospective cohort study of individuals aged 65 years or older sampled from Medicare eligibility lists nationwide.6 Institutional review board approval was waived for the current study. Participants provided written consent and were followed up semiannually. We excluded participants with a history of diabetes, hypertension, coronary disease, myocardial infarction (MI), AF, and CHF. We defined LAFB as a QRS axis between −45° and −90° and QRS duration of less than 0.12 seconds in the absence of left ventricular hypertrophy, inferior MI, and ventricular preexcitation on the baseline ECG.1 Outcome ascertainment for this study ended on June 30, 2008. We identified AF by study visit ECGs or hospital discharge diagnosis, and CHF was identified by physician diagnosis plus either pharmacological therapy or clinical findings. Deaths were identified from obituaries, the Social Security Death Index, Medicare claims, and participant proxies. Outcomes were compared using Kaplan-Meier estimates and Cox proportional hazards models. Adjusted comparative incidence rates (IRs) obtained from Poisson regressions are reported per 100 person-years. Covariates were chosen a priori or when associated with the predictor and outcome using a P value of less than .10 in the predictor and outcome. Participants having 1 or more covariates with missing data (n=183, 8%) were excluded from analyses involving missing variables. Data analysis was performed using Stata version 12 (StataCorp). Two-tailed P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

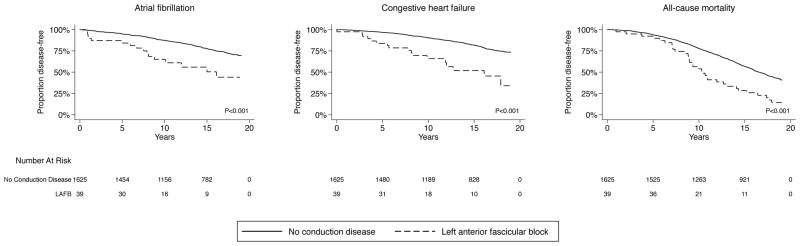

Of the eligible 1664 participants, the 39 individuals (2.3% [95% CI, 1.6%–3.1%]) with baseline LAFB were older and more likely male (TABLE). At follow-up (median 15.7, IQR 10.6–18.4 years), 380 participants had developed AF; 328, CHF; and 954 had died. Sixteen participants (41% [95% CI, 25%–57%]) with LAFB developed AF; 17 (44% [95% CI, 27%–60%]), CHF; and 33 (85% [95%CI, 73%–96%]) died. Through 10 years of annual ECGs, 0 LAFB participants developed left bundle branch block (LBBB) and 4 developed right bundle branch block, whereas 2 exhibited pacing. Participants with LAFB had an increased risk of AF, CHF, and death (FIGURE). After adjusting for age, race, sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, smoking, alcohol consumption, income, and study center, LAFB remained significantly associated with AF (hazard ratio [HR], 1.89 [95% CI, 1.11–3.24], P=.02; IR, 3.4 vs 1.8), CHF (HR, 2.43 [95% CI, 1.44–4.12], P=.001; IR, 3.5 vs 1.6), and death (HR, 1.57 [95% CI, 1.08–2.26], P= .02; IR, 6.2 vs 4.5). No meaningful differences were found when various baseline age cutoffs were applied. Also, LAFB was associated with death limited to cardiovascular causes (adjusted HR, 2.02 [95% CI, 1.08–3.77], P=.03; IR, 3.3 vs 1.8).

Table.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants Without Overt Cardiovascular Diseasea

| No. (%) of Patientsb | ||

|---|---|---|

| No Conduction Disease (n = 1625)c |

Left Anterior Fascicular Block (n = 39) |

|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 71.4 (5.0) | 74.9 (6.8)d |

| Male sex | 618 (38) | 25 (64)d |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)e | 25.1 (4.2) | 25.5 (4.2) |

| Systolic blood pressure, median (IQR), mm Hg | 122 (113–130) | 120 (114–128) |

| Race/ethnicityf | ||

| White | 1471 (91) | 33 (85) |

| Black | 147 (9) | 6 (15) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 3 (<1) | 0 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Other | 3 (<1) | 0 |

| Annual income, $ | ||

| <25 000, No./total (%) | 820/1512 (54) | 23/37 (62) |

| 25 000–49 999 | 427 (28) | 10 (27) |

| ≥50 000 | 265 (17) | 4 (11) |

| Current smoker, No./total (%) | 235/1624 (14) | 6/39 (15) |

| No. of alcoholic beverages consumed/wk | ||

| 0, No./total (%) | 698/1617 (43) | 17/39 (44) |

| <1 | 331 (20) | 5 (13) |

| 1–6 | 329 (20) | 9 (23) |

| 7–13 | 133 (8) | 5 (13) |

| >14 | 126 (8) | 3 (8) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

The normally distributed continuous variables were compared using t tests. Nonnormally distributed variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 and Fisher exact tests.

Unless otherwise indicated.

Referent group.

Comparison with referent group yielded a P value of less than .05.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Participants self-identified their race from the 5 investigator-specified categories listed. Race was assessed in the Cardiovascular Health Study to explore potential associations with cardiovascular disease. Race was included in this study as a potential confounder.

Figure.

Unadjusted Kaplan Meier estimates of proportions of individuals with left anterior fascicular block free of atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, or death.

Differences in proportions are compared using log-rank tests. Individuals with left anterior fascicular block more often developed atrial fibrillation (p<0.001), congestive heart failure (p<0.001), and death (p<0.001), when compared to those without conduction disease.

Discussion

In an older population without clinically manifest cardiovascular disease, LAFB was associated with an increased risk of AF, CHF, and death. Because no participants with LAFB went on to LBBB, and only 2 exhibited pacing throughout 10 years, it does not appear that progression of conduction disease was the reason for these observations.

Important limitations of this study include the small number of patients with LAFB and that this was an older cohort. Though CHS thoroughly identifies cardiovascular disease, it remains possible that LAFB is simply a marker of undetected underlying hypertension or coronary disease. Given previous histopathological studies,2,3 these findings suggest that LAFB may be a clinically relevant marker of an individual’s propensity to left heart fibrosis. Further research is needed to determine if LAFB is an important predictor of consequent adverse outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This publication was supported by the National Center for Research Resources, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, through grant TL1 RR024129. This research was also supported by contracts HHSN268201200036C, N01HC85239, N01 HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, and grants HL080295 and HL068986 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Additional support was provided by grant AG023629 from the National Institute on Aging and the Joseph Drown Foundation. A full list of principal Cardiovascular Health Study investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/PI.htm.

Role of the Sponsors: The funding organizations were not involved in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions: Ms Mandyam and Dr Marcus had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Mandyam, Soliman, Marcus.

Acquisition of data: Mandyam, Soliman, Heckbert.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Mandyam, Heckbert, Vittinghoff, Marcus.

Drafting of the manuscript: Mandyam, Marcus.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Mandyam, Soliman, Heckbert, Vittinghoff.

Statistical analysis: Mandyam, Vittinghoff, Marcus.

Obtained funding: Mandyam, Heckbert.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Mandyam.

Study supervision: Marcus.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Heckbert reported receiving grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr Vittinghoff reported receiving support for statistical consulting from the National Institutes of Health. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- 1.Elizari MV, Acunzo RS, Ferreiro M. Hemiblocks revisited. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1154–1163. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.637389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies M, Harris A. Pathological basis of primary heart block. Br Heart J. 1969;31(2):219–226. doi: 10.1136/hrt.31.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demoulin JC, Simar LJ, Kulbertus HE. Quantitative study of left bundle branch fibrosis in left anterior hemiblock: A stereologic approach. Am J Cardiol. 1975;36(6):751–756. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(75)90456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus GM, Yang Y, Varosy PD, et al. Regional left atrial voltage in patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4(2):138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Querejeta R, López B, González A, et al. Increased collagen type I synthesis in patients with heart failure of hypertensive origin: relation to myocardial fibrosis. Circulation. 2004;110(10):1263–1268. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140973.60992.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The cardiovascular health study: Design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1(3):263–276. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]