Abstract

Background

Due to the concentration of individuals at-risk for suicide, an emergency department visit represents an opportune time for suicide risk screening and intervention.

Purpose

The Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE) uses a quasi-experimental, interrupted time series design to evaluate whether (1) a practical approach to universally screening ED patients for suicide risk leads to improved detection of suicide risk and (2) a multi-component intervention delivered during and after the ED visit improves suicide-related outcomes.

Methods

This paper summarizes the ED-SAFE’s study design and methods within the context of considerations relevant to effectiveness research in suicide prevention and pertinent human participants concerns. 1,440 suicidal individuals, from 8 general ED’s nationally will be enrolled during three sequential phases of data collection (480 individuals/phase): (1) Treatment as Usual; (2) Universal Screening; and (3) Intervention. Data from the three phases will inform two separate evaluations: Screening Outcome (Phases 1 and 2) and Intervention (Phases 2 and 3). Individuals will be followed for 12 months. The primary study outcome is a composite reflecting completed suicide, attempted suicide, aborted or interrupted attempts, and implementation of rescue procedures during an outcome assessment.

Conclusions

While ‘classic’ randomized control trials (RCT) are typically selected over quasi-experimental designs, ethical and methodological issues may make an RCT a poor fit for complex interventions in an applied setting, such as the ED. ED-SAFE represents an innovative approach to examining the complex public health issue of suicide prevention through a multiphase, quasi-experimental design embedded in ‘real world’ clinical settings.

Keywords: suicide, research methods, mental health, emergency department

1. Background

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States. 1 Considerable federal effort has been directed towards reducing the national suicide rate. An emergency department (ED) visit may represent an opportune time to initiate suicide prevention efforts because a significant concentration of individuals at risk for suicide present to the ED for care.2 The average annual number of ED visits for attempted suicide and self-inflicted injury more than doubled from approximately 244,000 in 1993–1996 to 538,000 in 2005–2008.3 Studies conducted outside of the United States (U.S.) have found that nineteen percent of suicide attempters treated in the ED will re-attempt within the 6 months after the visit4, and 39% of completed suicides are by people who had been seen in an ED within the year before their death.5 When prospectively queried, rates of suicidal ideation among adult ED patients presenting with non-psychiatric chief complaints have ranged from 3 to 12%.6–10

Despite the likely density of at-risk individuals, most ED clinicians do not routinely screen for suicide risk. This is, in part, due to the paucity of evidence to support such screening. The human participants’ protections needs associated with managing such high risk individuals and the need for large sample sizes to test suicide reduction strategies due to the relative rarity of the event has discouraged research in this area. As a result, there are no suicide risk screeners validated for primary risk detection among adult ED patients. Despite the barriers to doing such research, the public health impact of preventing suicide argues for expanded efforts to develop and test feasible approaches to universal ED-based screening for suicide risk and effective interventions that can be initiated during or shortly after the ED visit. In response to this need, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) issued a Request for Applications, RFA-MH-09-150, and “Suicide Prevention in Emergency Departments.” Detailed information regarding the background leading up to the issuance of the RFA, as well as specific application requirements may be found on the National Institutes of Health website (http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-MH-09-150.html).

The Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE) was funded as a result of the RFA. ED-SAFE study has two primary objectives: (1) to develop and test the feasibility and effectiveness of a standardized approach to screening adult ED patients for suicide risk using a tool suitable for systematic use in general medical EDs; and (2) to refine and test an ED-initiated intervention to reduce suicidal behavior among people who screen positive for suicide risk. ED-SAFE attempts to examine both of these components (screening and intervention) in a single study. Studying both screening and intervention, the practical constraints of working within a ‘real world’ clinical setting, the methodological issues associated with studying rare events, and the high-risk nature of the patient population led to several important design considerations. The goal of this paper is to summarize ED-SAFE methodology, with a focus on design considerations, human participants’ protections, and intervention fidelity.i

2. Study design and procedures

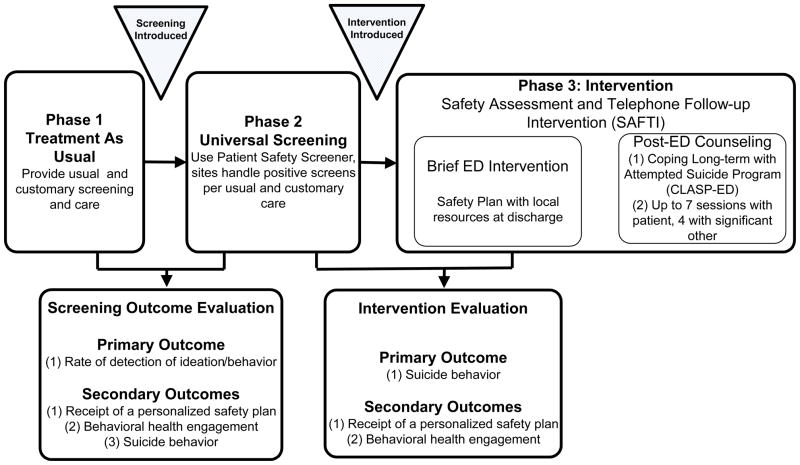

The study team decided to use a three phase, interrupted time series design to achieve the study’s dual objectives. The overall study approach is presented in Figure 1. It consists of three sequential phases of data collection Across all three phases, data collection will be standardized but suicide-related clinical protocols applied during routine care in the EDs will change. This is consistent with systems-based change and effectiveness research principles. Specifically, after the Treatment as Usual phase, all sites will implement universal suicide risk screening for adults as a standing clinical protocol. All adults treated in the EDs will be screened regardless of their reason for presentation or recruitment into the prospective subcomponent of the study. Data will then be collected for the Universal Screening Phase. After data collection for the Universal Screening Phase is complete, all sites will modify their clinical protocols to add enhanced secondary screening and discharge with outpatient suicide prevention resources, including a personalized safety plan and outpatient mental health resource guide. In addition, the post-visit telephone intervention, Coping Long-term with Active Suicide Program – Emergency Department (CLASP-ED), will be initiated. Data will then be collected for the Intervention Phase.

Fig 1.

Figure One: ED-SAFE Study Design

Data from these three phases will be used for two primary evaluations. Phases 1 and 2 (Treatment as Usual, Universal Screening) will be used to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of universal suicide risk screening (the Screening Outcome Evaluation). Phases 2 and 3 (Universal Screening, Intervention) will be used to determine the feasibility and effectiveness of the enhanced intervention combining improved ED safety planning and a postED telephone intervention in decreasing future suicidal behavior (Intervention Evaluation).

2.1 Study sites and participants

ED-SAFE has eight participating hospitals, ranging from small community hospitals to large academic medical centers (see Table One). In order to make the results generalizable to the field at large, no site has a stand-alone psychiatric ED. In each phase, sites will staff the ED with research assistants (RAs) who will prospectively review medical charts in “real time.” Any adult patient whom any level of self harm ideation or behavior documented on his or her ED medical chat will be considered eligible for approach. The threshold for initial approach will be kept low by approaching patients with any self-harm, not just suicidal self-harm per se, to avoid missing potential participants. The RAs will approach these individuals after they have been medically stabilized and sanctioned for approach by their treating clinicians, conduct an eligibility interview (see Table Two), and enroll a sample of 60 participants per site for each phase (480/phase), for a total of 1,440 prospective participants across the study.

Table One.

ED-SAFE Site Characteristics

| Name | Location | Annual ED Visit Volume (2009) | Council of Teaching Hospitals (COTH) | Primary Emergency Medicine Residency Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center | Boston, MA | 54,075 | Yes | Yes |

| Maricopa Medical Center | Phoenix, AZ | 50,000 | Yes | Yes |

| Marlborough Hospital | Marlborough, MA | 27,145 | No | No |

| Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island | Pawtucket, RI | 31,463 | Yes | No |

| Ohio State University Medical Center | Columbus, OH | 48,753 | Yes | Yes |

| University of Arkansas Medical Center | Little Rock, AR | 39,430 | Yes | Yes |

| University of Colorado Hospital | Aurora, CO | 43,903 | Yes | No |

| University of Nebraska Medical Center | Omaha, NE | 51,083 | Yes | Yes |

Table Two.

Eligibility Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

All RAs will be trained centrally on the data collection procedures through multi-media teleconferences and supervised locally by an experienced emergency medicine investigator. The site will be given a detailed manual of procedures, and the site personnel will meet with ED-SAFE study leadership for monthly teleconference call to review progress, receive training updates, and problem solve.

2.2. Study oversite

A Steering Committee will direct and oversee the operations of the study. Study materials will be generated centrally at the coordinating center at Massachusetts General Hospital and distributed to the sites for submission to their respective Institutional Review Boards. NIMH will appoint an independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) with authority to shut down the study.

2.3 Outcome assessments

Across all three phases, outcome data collection will be performed in the same way. During each RA shift, all patients who enter the ED will be documented on a screening log, which will be used as the primary data for the Screening Outcome Evaluation to determine if screening and detection of suicidal ideation or behavior is impacted by the implementation of universal screening protocols. The log will contain basic demographic information and will indicate if the individual’s chart documented any screening for self harm ideation or behavior. If such screening is documented on the chart, the RA will note whether the screen is negative (i.e., self harm ideation or behavior is documented as not present) or positive (i.e., self harm ideation or behavior is documented as present), and will be further classified by the RA as current (i.e., occurring during or immediately preceding the current ED visit); past (i.e., noted in the past but not currently); or unknown time (documented but without any clear time reference). All individuals with self harm will be approached by the RA and further evaluated specifically for suicidal ideation and behavior within the past week.

The participants who are enrolled into the prospective portion of the study will be followed post-discharge (from ED or inpatient, if admitted) using a multi-method approach. Follow-up assessments will occur 6, 12, 24, 36, and 52 weeks after discharge. Patient reported outcome assessments will be done through a centralized call center staffed by trained technicians blinded to baseline data. The study team chose the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (CSSRS)11 as the primary instrument for assessing suicidal ideation and behavior based on the need to assess both suicidal ideation and behavior, its ease of the training, and its widespread use in clinical trials.

Table Three outlines the additional domains assessed and the schedule of assessments. In addition to the data gathered through the assessment calls, state and national vital statistics registries will be used to track participant outcomes for 12 months. Due to the variation in access to vital statistics registries between states, each site will develop its own protocol on how to access the registries, with guidance from study investigators. A uniform abstraction tool will be used to ensure similar data collection approaches across sites. A final review of the National Death Index will occur 24 months after the final participant is enrolled to validate the site level reviews. Finally, administrative databases associated with the site’s healthcare system will be reviewed to monitor healthcare utilization, including ED visits and hospitalizations, both related and unrelated to self harm.

Table Three.

Schedule of Follow-up Assessments

| Construct | Method | Instrument | Time (B=baseline; other times in weeks) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Calls | ||||||||

| B | 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 52 | |||

| A. Demographics, contact information | INT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| B. Suicidal ideation, lifetime, interval | INT | CSSRS11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| C. Suicidal behavior, lifetime, interval | INT, DR, AD, CR | CSSRS11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| D. Non-suicidal self- injury (NSSI) | INT | Modified Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| E. Healthcare utilization | INT, AD, CR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| F. Lethal means restriction | INT | Various 20–22 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| G. Psyc. Distress | INT | Brief Symptom Checklist23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| H. Alcohol use | INT | AUDIT, short24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| I. Drug use | INT | Drug screener25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| J. Quality of life | INT | SF-6D26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

INT=Interview; DR=death registries; AD=Healthcare administrative database; CR=Chart review AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; SF-6D = Short Form Health Survey – 6D

2.4 Study phases

The three sequential study phases (conditions) are summarized below.

Phase 1: Treatment as usual

The primary goal of Phase 1 (Treatment as Usual) is to provide baseline detection data that will serve as the control for the Universal Screening phase. Over the course of first ten months of the study, RAs at each of the eight sites will prospectively screen charts for documentation of intentional self harm. Patients will be treated according to the usual and customary care at the specific site, enabling a determination of the site’s natural rate of screening and detection of self harm ideation and behavior.

Phase 2: Universal screening

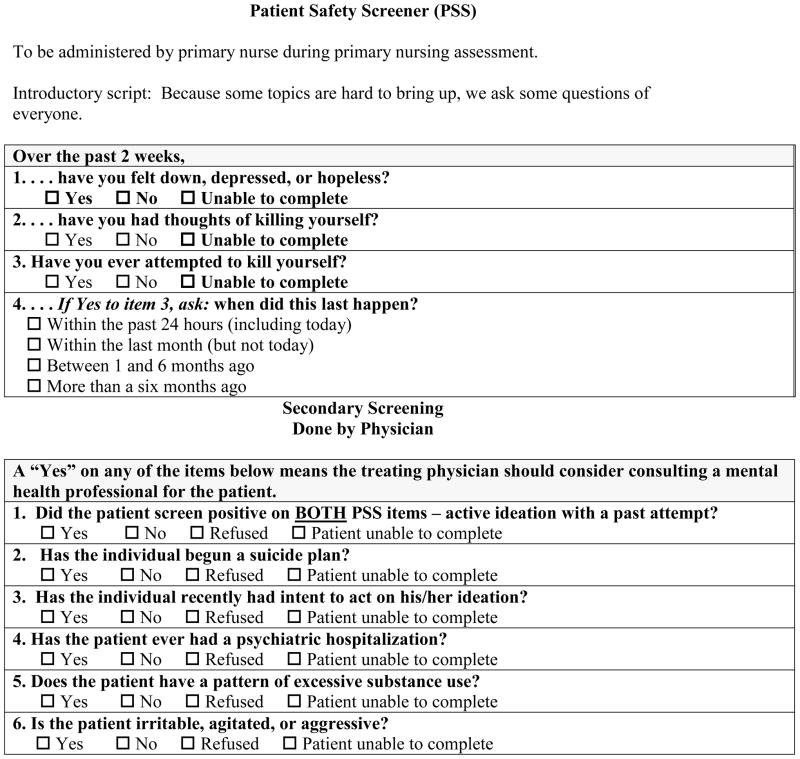

As there are no validated primary suicide screening instruments that have been used for universal screening purposes in ED settings, one was created for this study. The three-item Patient Safety Screener (PSS) (see Figure Two) begins with the depressed mood item from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ).12 While not strongly predictive of suicide in and of itself, we believe it will be more clinically acceptable to patients to include the PHQ depression item as a “lead in” to the suicide questions; an assessment of mood will allow for an easier transition to an assessment of suicidal thoughts/behavior. The other two items assess active ideation (thoughts of killing oneself) and lifetime suicide attempt, with a follow-up question assessing the timing of the most recent attempt for those with a history of attempt. A “positive screen” will be individuals who either endorse active ideation or report a suicide attempt within the past 6 months.

During the Universal Screening phase, sites will incorporate the PSS into their standard clinical protocols. To guide the transition from Treatment as Usual (Phase 1) to Universal Screening (Phase 2), each site will create a performance improvement team to modify the site’s policies and procedures and oversee the implementation of the PSS. Sites will use the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle methodology, a performance improvement technique commonly applied in healthcare settings.13 Online webinars will be used to provide standardized training to all sites in performance improvement methods and the creation of clinical guidelines. Conference calls between the site investigators, RAs, and the study’s principal investigators will occur on a regular basis to discuss progress, challenges, and solutions to implementing screening.

While there may some natural variation in screening procedures across sites, key aspects of the screening process will be standardized. At all sites, the primary treating nurse, rather than the triage nurse, will conduct the screening; screening during triage will only occur for those cases presenting with a primary psychiatric complaint. The triage nurse often has limited time available and the conditions of triage are typically not ideal for asking highly sensitive questions. The primary nurse, however, has more time with the patient, is usually in a secluded treatment area, and has the opportunity to build rapport prior to asking more sensitive questions. These conditions are more likely to result in the administration of the screening questions and to yield honest patient responses. The screener will be embedded in the standardized chart templates or electronic health records at each site to promote and support its use.

During the Universal Screening Phase sites will be encouraged to further evaluate and treat individuals who screen positive, but the study will not be providing standardized treatment protocols. This study phase will examine screening in the absence of a standardized intervention so that we may obtain a clearer understanding of outcomes following mandated screening (see Section 2.5 for elaboration on how this will be done).

Phase 3: Intervention

During the Intervention Phase, sites will continue to administer the PSS as they did during the Universal Screening Phase. Patients who screen positive will be further evaluated by their treating physician, as is typically done. However, added in Phase Three, we will recommend the treating physician use a secondary screener consisting of a brief review of risk factors commonly associated with suicide (Figure Two) to aid in the decision to consult a mental health specialist. Like the primary screener, the secondary screener was created for the study, and it consisted of well-known risk factors, including the presence of suicidal intent or plan, previous psychiatric hospitalization, excessive substance use, and irritability, agitation, or aggression. The risk factors were chosen based on a review of the literature to identify the strongest and most consistent predictors among ED patients and the clinical experience of the Steering Committee. The list was reviewed by external experts unaffiliated with the study.

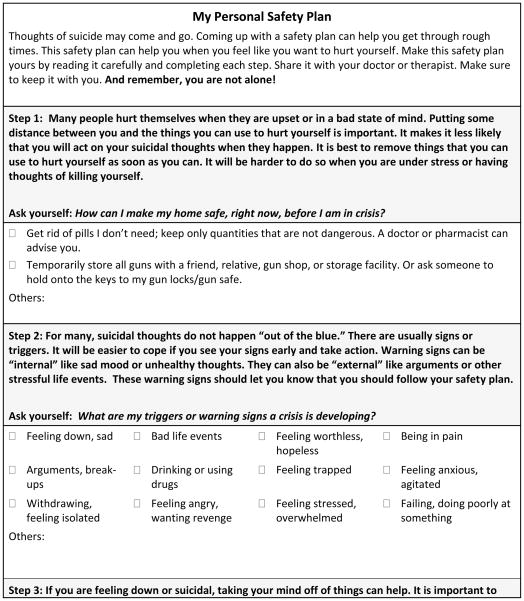

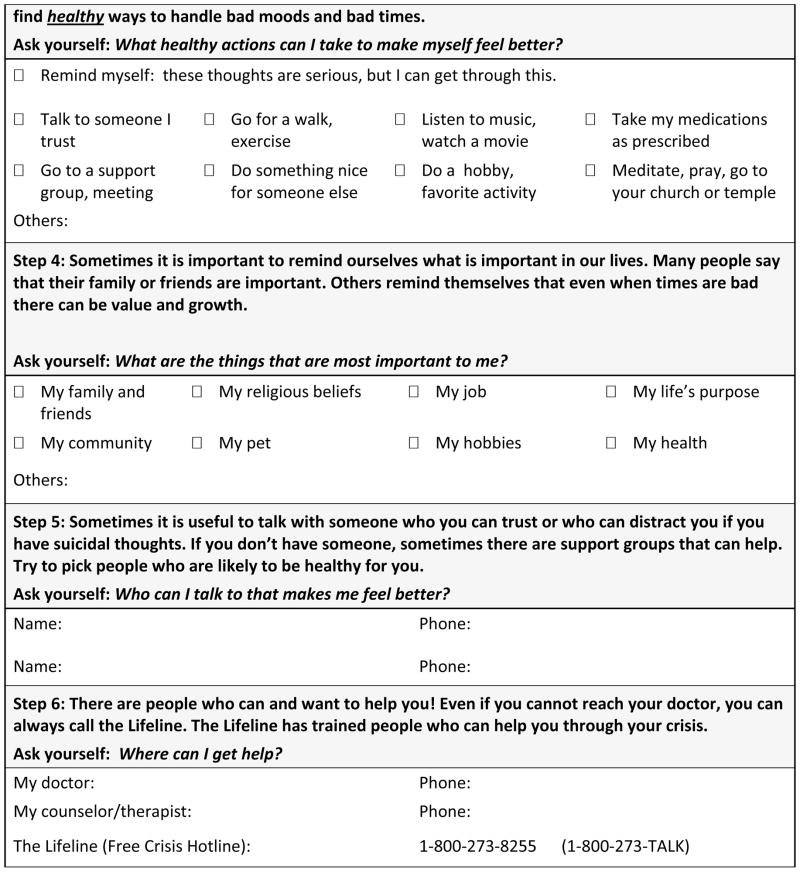

In addition, as part of this phase, all individuals who screen positive on the PSS, regardless of whether or not they receive a mental health consultation, will receive a printed safety plan that will include community resources and hotline numbers (see Figure Three). A safety plan is a structured tool that helps individuals identify early warning signs for suicidal behavior, internal and external coping resources, and plans for accessing social support and professional help if their first-line coping strategies do not work to reduce their suicidal thoughts. The safety plan was modeled after work by Stanley and Brown14, but it is designed to be self-administered by the individual rather than therapist guided. The patient’s primary nurse will be responsible for reviewing the safety plan’s purpose and instructions for completing it with the patient upon discharge. We considered having the nurse complete the safety plan with the patient but the logistical demands associated with providing care in the ED do not support such a time-intensive, interactive strategy. Besides standardizing the primary screening, recommending the secondary screener be used to help decide whether psychiatry needs to be consulted, and requiring all individuals who screen positive on the primary screener receive outpatient suicide prevention resources, we did not standardize decision making or require any additional intervention components during the ED visit.

Following the ED visit, all eligible and consenting participants in this phase (n=60/site) will participate in a telephone-based intervention designed to reduce subsequent suicidal behavior and help promote outpatient treatment engagement. This intervention is a modification of the Coping Long-term with Active Suicide Program (CLASP) [Miller, R34MH073625, R01AA015950]. The CLASP-ED intervention is an adjunctive intervention that combines principles of case management, individual counseling, and family/significant other mobilization. Patients will receive up to seven telephone calls from a trained “advisor,” while their significant other will receive up to four calls (with permission from participants). The schedule and content of the calls are summarized in Table Four. The CLASP-ED intervention will be centrally delivered by trained staff from Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island.

Table Four.

CLASP-ED Session Content Summary

| Timing | Contact | Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 (ASAP after discharge from ED/hospital) | Patient |

|

| Week 2 | Patient |

|

| Week 3 | Significant Other* |

|

| Weeks 4, 10, 22, 34 and 48 | Patient |

|

| Weeks 8, 20 and 32 | Significant Other |

|

Significant others will be recruited to assist if there are emergencies

2.5 Analysis Plan.ii

The Screening Outcome Evaluation examines the first step for prevention – detection of risk -- by comparing suicide screening and detection before and after universal screening is implemented. We hypothesize that implementing universal screening will increase detection of suicidal ideation and behavior when compared to Treatment as Usual. Data from the screening logs maintained during Phases 1 (Treatment as Usual) and 2 (Universal Screening) will be analyzed to determine if screening increased detection of suicidal ideation or behavior. First, we will determine if the screening rate actually increases after we implement the clinical protocol (i.e., do nurses actually carry out the protocol?). This will be determined by examining proportion of patients in the Screening Log who have any self-harm screening documented. If universal screening is implemented with fidelity, the proportion of patients who have any screening documented should increase between Phase 1 and Phase 2. Moreover, we will set as our target goal for Phase 2 that 75% of patients should have a documented screening; we did not set it to 100% because there are legitimate reasons why ED patients might not be screened, including altered mental status and emergency medical conditions.

Because the Screening Log will not only document whether a screening for self-harm risk was performed but also the outcome (i.e., whether there was self-harm ideation or behavior present or absent), we shall be able to determine whether detection of self-harm risk increases after universal screening by calculating the proportion of total patients in Phase 1 and Phase 2 who are positive for self-harm ideation or behavior.

The Intervention Evaluation will rely on data collected during Phases 2 (Universal Screening) and 3 (Intervention). We hypothesize that fewer participants enrolled during the Intervention phase will exhibit suicidal behaviors in the 12 months following the ED visit when compared to participants enrolled during the Universal Screening phase. This will be the suicide outcome data for the participants enrolled into the longitudinal portion of the study.

3. Methodological Considerations

In planning the study, there were several key considerations focused on the design itself, strategies for case identification, approaches to outcome assessments, and blinding.

3.1 Study design

We chose an interrupted time series design, rather than a randomized design, because we wanted to assess the impact of implementing systems-based changes, and designs involving site or individual level randomization did not seem appropriate given our study aims and certain constraints (e.g., budget, setting, etc). A cluster randomized trial was judged to be prohibitively expensive due to the required number of sites, which was estimated to be greater than 40. Designs requiring individual level randomization are a poor fit for screening studies, because randomly assigning patients to be screened or not by the treating nurse is logistically impossible.

Several methodological controls will be incorporated to help reduce artifact and bias. First, larger census sites might have greater access to mental health resources, are more likely to be affiliated with an academic teaching hospital, and may have other characteristics that could be independently related the outcomes. Consequently, the eight sites will be characterized based on whether they have higher or lower than the median census, randomly assigned to one of four cohorts, and randomly assign to a start date, with the start dates spaced approximately two months apart. This approach should help control for confounding site differences that may be introduced by the size of the hospital by ensuring that similar census sites do not all start at the same time. Moreover, the staggered start times for each cohort will help to control for historical effects, such as naturally rising screening rates, by allowing comparisons within similar time periods across sites in different stages. For example, while the last cohort to start, cohort four, is finishing the Treatment as Usual phase, the first cohort to start, cohort one, will be implementing Universal Screening. By comparing the changes in screening rates for this overlapping time period across cohorts in different phases of the study, we can deduce whether increases in screening rates were truly due to the implementation of the intervention, per se, or were simply naturally rising because of historical or secular trends. .

3.2 Case identification

To help avoid selection bias and maintain standardization across all sites and RAs, several procedures will address case identification and selecting individuals for study participation. First, training on all research protocols will be centralized and all sites will use a standardized manual of procedures. Second, in deciding whether to approach an individual for eligibility screening, RAs will use the threshold of any self harm, based on chart review, not just suicidal self harm. Second, all RAs will use a set of standard questions in a computer guided interview to limit subjectivity and exclude ambivalent cases (e.g. patients with an ambiguous overdose of recreational drug use who are not trying to kill themselves). If the individual denies any intent to die, he or she will be considered ineligible. This two stage process of low threshold chart review and standardized eligibility screening helps to assure that we do not miss anyone who is potentially suicidal while only enrolling into the trial patients who are clearly suicidal, and centralizes (or standardizes) the eligibility determination, limiting site/RA level variability with respect to case identification.

Despite these controls, the samples collected across each of the three phases may still comprise different kinds of participants, and these differences may be related to the outcomes of interest. For example, patients who are enrolled in the treatment as usual phase may be more severely suicidal than those in the later phases, which could artificially inflate the intervention effect because the less severe patients enrolled during the later phases may have a lower likelihood of attempting suicide. In order to limit this potential bias, we will aim to enroll approximately half of each phase with participants who have actually attempted suicide within the past week (including the current ED visit) and half who have active suicidal ideation but no attempt within the past week. This equal representation of attempters and ideators will help to balance the sample composition for suicide risk severity across phases to help counteract selection bias. Finally, data analyses will be conducted to confirm that the composition of each group is equivalent and variances will be adjusted statistically. While there are sophisticated stratified sampling methods to help account for this kind of selection bias, they were judged to be infeasible for practical reasons (e.g., the time to enroll a sufficient sample would exceed the four year study period).

3.3 Outcomes and Power Calculations

The outcomes of interest reflect both systems-level data (screening and detection outcomes) and individual-level data (suicide behavior outcomes). It is unusual to have a study in which the primary outcomes, and therefore the unit of analysis, will occur at two levels. This has a practical effect on data collection methods. Specifically, it required data to be collected to identify if the system changed, such as through RA collection of screening log data, in addition to data reflecting individual impact, such as telephone follow-up after the ED visit. It also impacted analytic strategies, which required two separate data analytic plans to address the Screening Outcome Evaluation and the Intervention Evaluation separately (Figure 1). The multiple study outcomes made the power analysis difficult.

Briefly, we decided to power the trial based on the individual level outcome of suicide behavior, then examined how this would influence the power for the systems-level outcomes (i.e., screening and detection). Moreover, we determined the target sample of suicidal patients per phase by the needs of the Intervention Evaluation because the Screening Outcome Evaluation (phase 2 vs phase 1) and the Intervention Evaluation (phase 3 vs phase 2) would share data collected during the Universal Screening phase and we also wanted to power the study to allow a conditional post-hoc test using the Treatment as Usual phase (i.e., a comparison of phase 3 vs phase 1). The latter comparison would allow us to assess whether the Intervention led to better suicide outcomes than usual care. We recognized that the possibility that Universal Screening might be sufficient to improve suicide outcomes. If true, this would attenuate the difference between the Universal Screening and Intervention phases; the improvement from the intervention might not be statistically different from Universal Screening but, nevertheless, would represent a significant enhancement over Treatment as Usual.

Given the dearth of published data from which to derive base rate and effect size estimates, we made conservative assumptions to protect against under-powering. We set our anticipated proportion of the suicide composite in the Universal Screening phase at 20% over the 12 months post-visit versus 13% in the Intervention group. Under these assumptions, with an alpha <0.05 and beta 20%, and assuming a compound symmetry covariance structure and within-person correlation of 0.7, the study would need to have 328 participants enrolled during each of the two phases. This would give us 80% power to detect a relative risk of 0.65. Because we anticipate an attrition rate of approximately 30% for telephone follow-up over 12 months in this patient population, we decided to oversample to 472 participants per phase. Finally, because we wanted to power the study to allow for the conditional post-hoc test, we also sought to recruit 472 participants in the Treatment as Usual phase.

Returning to the comparisons at a systems-level, our estimates of the number of patients who would have to be seen in the ED during RA shifts, and therefore logged into the screening log for the Screening Outcome Evaluation, in order to enroll the targeted number of participants for the prospective part of the study (n=60/site/phase) suggested there would be ample data recorded on the screening log to detect even small to modest improvements in suicide risk detection, such as an absolute improvement from 3 to 5% positive detection. This was important because even small differences in an outcome as important as suicide behavior, when applied to large populations, can translate into enormous public health impact.

Because of the unique requirements of researchers to act on suicide risk when assessed, the frequency and timing of the follow-up telephone assessments was very important. Assessments will occur 6, 12, 24, 36, and 52 weeks after discharge (see Table Three). In order to improve the validity of the assessments, participants must be interviewed frequently enough so that memory bias or forgetting will not be a major factor. However, because the responsibilities inherent in monitoring suicidal patients require the researcher to act if an individual is above a risk threshold, the number of assessments should be minimized to avoid introducing a contaminating effect.15,16, 17 As clearly outlined by Oquendo et al.17, if the suicide monitoring and human participants protection procedures are “too good, the outcome measure rate may decrease in a way that is inconsistent with “real world” conditions, which at a minimum diminishes the study’s ecological validity and at worst makes the study impossible to conduct.” (p. 1559). The assessment schedule was judged to be a reasonable balance between the goals of maintaining the scientific integrity of the study with the need for strong human participants’ protections.

3.4 Blinding

In a study such as this, it is impossible to fully blind participants to their condition. They must provide informed consent and thereby are given knowledge about the condition to which they are consenting. However, as will be described in a later section, by using serial consent forms specific to each phase, each participant will only knows about the condition to which he or she is consenting. Individual participants will not know that there are other conditions, since these other conditions will not happen contemporaneously and it will never be an option for the individual to potentially be assigned to the other conditions. As a result, the participant will be partially blinded in that he or she will not have knowledge of the contrast between the condition in which he or she is enrolled and comparison conditions. To help reduce selection bias, the consent process will be kept as similar as possible for each of the three phases.

It is also impossible to blind the clinical staff – they are trained to perform the screening and interventions, so they have full awareness of the phases of the study. The outcome assessors will be blinded to baseline data, including the participant’s phase of enrollment, but they will know about the different phases of the study and are likely to be able to determine which participants are enrolled in which phase. This is unavoidable and will be partially mitigated by using a standardized, computer assisted telephone interview to help reduce the influence of interviewer bias and the collection of objective data from vital statistics registries and healthcare administrative databases.

4. Human Participants Considerations

The potential ethical/human participant issues involved when studying patients with high suicide risk has resulted in decreased research efforts involving this population. Recognition that these potential ethical issues have severely hampered research and, in turn, limited progress in our knowledge of how to best treat suicidal patients has led to the publication of several papers providing guidelines for addressing these human participants issues so that the research can occur.15–17 These guidelines informed our decision making with respect to human participants considerations when designing the trial.

4.1 Informed consent

Because screening is being implemented system wide during routine clinical care, patients will not consent to the screening. However, across all three phases, RAs at each site will obtain written informed consent for study participants who are enrolled into the prospective clinical trial portion of the study. Because ED-SAFE is not a randomized trial, and individuals are enrolled at the time of their ED visit, a potential participant will be eligible for only one condition (an individual who enrolled in one phase is ineligible for subsequent phases). All consent forms will describe the expectations associated with participation, including the telephone follow-up assessments, risks/benefits, the limits to confidentiality, and the Certificate of Confidentiality obtained, but will not discuss alternative conditions.

In Phase 3 (Intervention), identification of a significant other that can be included in the intervention will be encouraged, though not required. The significant other can be anyone whom the participant identifies, including a spouse, romantic partner, family member, or friend. If the study participant agrees, the designated significant other will be contacted via telephone. During the first call to a significant other, the patient advisors (interventionists) will fully explain the study procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives and obtain audio-recorded, verbal informed consent. Although written informed consent is preferable to verbal consent, obtaining written consent will not be feasible because of the clinical need for timely initiation of contact with the significant other, difficulties physically locating significant others, and the burden on significant others if required to have face-to-face contact with research personnel. We will, however, send a copy of a written informed consent form to the significant other, and will request, but not require, that it be signed and returned to research staff.

4.2. Clinical back-up for assessments

While the individuals making the outcome assessment calls will be trained to conduct the outcome assessment protocol, they will not be mental health professionals. Given the high risk nature of the study population, we felt it prudent to have clinical back-up available in the event that imminent risk for suicidality was identified during an assessment call. The decision was made to use the resources available for telephone counseling through Boys Town National Hotline, which is part of the national network of crisis centers forming the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8355; www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org) and provides crisis intervention services to both adults and children. As part of their training in ED-SAFE study protocols, call center staff conducting the outcome assessments will be trained on when and how to connect study participants with a Boys Town crisis counselor. A study participant will be referred to Boys Town if they report: 1) active suicidal ideation at the time of an assessment call, or 2) a suicide attempt since the last call that was not treated by a health care professional. Prompts will be built into the computer assisted telephone interview to alert the call technician when either of these conditions is present. Other situations which may lead to the interviewer connecting the study participant with the Boys Town National Hotline would be if the study participant is extremely distressed during the interview, makes ambiguous or evasive innuendos suggestive of imminent suicidal ideation or intent, or there is an imminent risk of harm to others.

When connecting the study participant with the Boys Town National Hotline, the interviewer will inform the participant that s/he will be connected directly with a crisis counselor, and will be placed on hold briefly while the connection is made. The participant will be asked not to hang up during this time. The interviewer will convey pertinent information to the crisis counselor including the participant’s contact information and the contact information for the participant’s emergency contact. After this information has been given to the crisis counselor, the interviewer will connect the participant to the crisis counselor, leave the call, and follow up with an email of the information to Boys Town.

5. Intervention Fidelity

Fidelity to intervention protocols are a critical component for any research project, particularly when, as is the case with ED-SAFE, the protocol is being implemented in ‘real world’ settings. When assessing a health behavior treatment, three strategies have been targeted for improving and measuring treatment fidelity: using a treatment manual, developing strategies to train and maintain provider skills, and checking adherence to protocol.18 Monitoring the implementation of the ED-SAFE intervention protocols will be addressed by multiple overlapping activities. First, we will provide each participating site with a manual of procedures containing step-by-step instructions for each phase of the study. Second, all clinical staff at each site will be trained by site-trainers who will be trained by the study principal investigator and the ED-SAFE training director via webinars and teleconferences. Third, we will integrate study interventions (e.g., the suicide screener) into the pre-existing local medical documentation templates or electronic health records. This will increase the likelihood that the screener is completed by being an integral part of the medical record rather than a separate form. It will also create a more streamlined process for nursing staff to include the screener as part of their initial assessment.

We will measure protocol fidelity through chart reviews and patient interviews. The patient interviews will occur during the Universal Screening and Intervention phases. These interviews will be completed with a random subset of ED patients whose medical record indicates either an absence of suicidality (i.e., a “no” on the screening items) or has no screening documented. This interview will be completed by the research assistant and will ask the patient if he or she was asked the suicide screening questions by their nurse during the visit. These data will allow us to determine the proportion of patients with a negative screener or no documentation who were actually asked the suicide screening questions in the ED (versus simply documenting a negative screening but not actually asking the patient the question). The results of the chart reviews and patient interviews will be presented to the ED clinical staff on an ongoing basis; providers will be given graphs to track the progress of their performance (e.g., universal screening, documentation of secondary screening). In addition, during the Intervention phase, patients will be questioned by their CLASP-ED telephone advisor about several aspects of their ED care, including whether they were counseled, received a printed safety plan, and were given a referral list.

Conclusion

ED SAFE represents an example of an alternate approach to the randomized clinical trial when conducting suicide prevention research. The results of this study will help establish the feasibility, effectiveness, and sustainability of a multi-component screening and intervention for suicide within general ED settings, will have significant practical implications for the prevention of suicide.

Fig 2.

Figure Two: Screeners

Fig 3.

Figure Three: Personal Safety Plan Template

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the time and effort of the research coordinators and research assistants from the 8 participating sites. ED-SAFE Investigators Not Listed as Author Michael Allen, MD (University of Colorado Denver) Edward Boyer, MD, PhD (University of Massachusetts) Jeffrey Caterino, MD (Ohio State University Medical Center) Robin Clark, PhD (University of Massachusetts) Mardia Coleman (University of Massachusetts) Barry Feldman, PhD (University of Massachusetts) Talmage Holmes, PhD (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Medical Center) Maura Kennedy, MD (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) Frank LoVecchio, DO (Maricopa Medical Center) Lisa Uebelacker, PhD (Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island) Wesley Zeger, DO (University of Nebraska Medical Center)

Disclosures: The project described was supported by Award Number U01MH088278 from the National Institute on Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. None of the authors have financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Several aspects of the study, including the adverse event monitoring system, a provider knowledge and attitudes survey, and an economic analysis are considered beyond the scope of the current discussion. All of these sub-studies will be addressed in forthcoming manuscripts.

For practical reasons, we do not discuss our planned statistical analyses here but, rather, simply outline the major comparisons that will be made. The specific analyses will be detailed in the primary manuscripts.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Edwin D Boudreaux, Departments of Emergency Medicine, Psychiatry, and Quantitative Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA.

Ivan Miller, Butler Hospital and the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Amy B Goldstein, Division of Services and Intervention Research, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Ashley F Sullivan, Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

Michael H Allen, University of Colorado Depression Center and VISN 19 MIRECC, Aurora CO.

Anne P Manton, Cape Cod Hospital / Cape Psychiatric Center, Cape Cod, MA.

Sarah A Arias, Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

Carlos A Camargo, Jr., Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) 2012 www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

- 2.D'Onofrio G, Jauch E, Jagoda A, et al. NIH Roundtable on Opportunities to Advance Research on Neurologic and Psychiatric Emergencies. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(5):551–564. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.06.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ting SA, Sullivan AF, Boudreaux ED, Miller I, Camargo CA., Jr Trends in US emergency department visits for attempted suicide and self-inflicted injury, 1993–2008. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. May 2; doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beautrais AL. Further suicidal behavior among medically serious suicide attempters. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34(1):1–11. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.1.1.27772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gairin I, House A, Owens D. Attendance at the accident and emergency department in the year before suicide: retrospective study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003 Jul;183:28–33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudreaux ED, Clark S, Camargo CA., Jr Mood disorder screening among adult emergency department patients: a multicenter study of prevalence, associations and interest in treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008 Jan-Feb;30(1):4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boudreaux ED, Cagande C, Kilgannon JH, Clark S, Camargo CA. Bipolar Disorder Screening Among Adult Patients in an Urban Emergency Department Setting. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(6):348–351. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v08n0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boudreaux E, Baker C, Huang D, et al. Validation of depression and bipolar disorder screening among emergency department patients. Ann Behav Med. 2005:29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claassen CA, Larkin GL. Occult suicidality in an emergency department population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005 Apr;186:352–353. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilgen MA, Walton MA, Cunningham RM, et al. Recent suicidal ideation among patients in an inner city emergency department. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2009 Oct;39(5):508–517. doi: 10.1521/suli.2009.39.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Valildity and Internal Consistency Findings From Three Multisite Studies with Adolescents and Adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A New Depression Diagnostic and Severity Measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32(9):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berwick DM. Continuous improvement as an ideal in health care. N Engl J Med. 1989 Jan 5;320(1):53–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901053200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety Planning Intervention: A Brief Intervention to Mitigate Suicide Risk. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson JL, Stanley B, King CA, Fisher CB. Intervention research with persons at high risk for suicidality: safety and ethical considerations. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62(S25):17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nierenberg AA, Trivedi MH, Ritz L, et al. Suicide risk management for the sequenced treatment alternatives to relieve depression study: applied NIMH guidelines. J Psychiatr Res. 2004 Nov-Dec;38(6):583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oquendo MA, Stanley B, Ellis SP, Mann JJ. Protection of human subjects in intervention research for suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Sep;161(9):1558–1563. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borrelli B, Sepinwall D, Ernst D, et al. A new tool to assess treatment fidelity and evaluation of treatment fidelity across 10 years of health behavior research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005 Oct;73(5):852–860. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, Michel BD. Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview: development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychol Assess. 2007 Sep;19(3):309–317. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okoro CA, Nelson DE, Mercy JA, Balluz LS, Crosby AE, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of household firearms and firearm-storage practices in the 50 states and the District of Columbia: findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2002. Pediatrics. 2005 Sep;116(3):e370–376. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Betz ME, Barber C, Miller M. Suicidal behavior and firearm access: results from the second injury control and risk survey. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2011 Aug;41(4):384–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller M, Barber C, Azrael D, Hemenway D, Molnar BE. Recent psychopathology, suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts in households with and without firearms: findings from the National Comorbidity Study Replication. Inj Prev. 2009 Jun;15(3):183–187. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.021352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI® 18) Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Canada Assessment Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): Guidelines for use in primary care. 2. World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boudreaux ED, Bedek KL, Gilles D, et al. The Dynamic Assessment and Referral System for Substance Abuse (DARSSA): development, functionality, and end-user satisfaction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009 Jan 1;99(1–3):37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ. 2002 Mar;21(2):271–292. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]