Abstract

We explored intra-urban mobility of Tijuana, Mexico injection drug users (IDUs). In 2005, 222 IDUs underwent behavioral surveys and infectious disease testing. Participants resided in 58 neighborhoods, but regularly injected in 30. From logistic regression, “mobile” IDUs (injecting ≥3 km from their residence) were more likely to cross the Mexico/U.S. border, share needles, and get arrested for carrying syringes - but less likely to identify hepatitis as an injection risk. Mobile participants lived in neighborhoods with less drug activity, treatment centers, or migrants, but higher marriage and home ownership rates. Mobile IDUs should be targeted for outreach and further investigation.

Keywords: Injection drug use, mobility, distance, GIS, neighborhood context

Introduction

Almost half the world’s population now lives in an urban setting, with nearly all living in or very near to an urban environment in developed nations (United Nations Population Division, 2008). However, urban areas are diverse, and even within a single city social, structural, and economic disparities between neighborhoods may affect the context in which health concerns arise (Gorin et al., 2007; McConnochie et al., 1999; Osypuk & Acevedo-Garcia, 2008). Further, while insularity of neighborhoods and social networks within them might be protective in terms of infectious disease transmission, factors promoting disassortative mixing, such as intra-urban mobility, might increase transmission risk.

Injection drug users (IDUs) have long been recognized as a population at risk for blood borne infections, including HIV, hepatitis B and C, and HTLV-I and II. In various international settings, there has been concern that IDUs who engage in risky behaviors outside their areas of residence could potentially transmit infections to other IDU and non-IDU populations within and between countries (M. Williams, Atkinson, J, Klovdahl, A, Ross, MW, Timpson, S, 2005). For example, in Brazil, receptive needle sharing among highly mobile IDUs was associated with transmission of malaria from an endemic to a non-endemic region (Bastos, Barcellos, Lowndes, & Friedman, 1999).

At 1.4 million inhabitants and an annual growth rate of 4–5%, Tijuana is one of Mexico’s largest cities (Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI), 2008). Cross-border travel between Mexico and the United States is common, as the San Ysidro border crossing between San Diego and Tijuana comprises the busiest land border crossing in the world (San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG), 2007). However, travel within the sprawling city of Tijuana is also common, with the greater metropolitan area covering some 1,240 square kilometers (Periódico Oficial del Estado de Baja California, 1995). Tijuana is also situated on a major drug trafficking route for heroin, methamphetamine, and cocaine (Brouwer et al., 2006; Bucardo et al., 2005). It is in this context that the city has experienced burgeoning epidemics of injection drug use and HIV. There are estimated to be 21,000 illicit drug users in the city, and of these an estimated 10,000 are IDUs (Magis-Rodriguez et al., 2005; Trillo, 2002).

Mobility of IDUs between cities and across international borders can take place for a variety of reasons, including escaping social controls and increasing access to drugs (Dehne, 1999; Drucker, 1990; Rachlis et al., 2007; Uriely, 2005). IDU migration has been linked with spread of the HIV epidemic and, in some contexts, barriers to accessing medical care or drug treatment (Brouwer et al., 2009; Dehne, 1999; Drucker, 1990; Rachlis, et al., 2007). Considerably less is known about intra-urban mobility of IDUs. While some studies have explored access to drug treatment and care in regards to proximity to services within a city (Rockwell, Des Jarlais, Friedman, Perlis, & Paone, 1999; Sarang, Rhodes, & Platt, 2008) - in the present study we use a spatial approach to better understand neighborhood and individual-level characteristics of IDUs who often travel within a city. We hypothesized that drug users who live and inject in different parts of a city might be from neighborhoods with higher socio-economic status, given the cost of intra-urban transportation and stigma or other social pressures which might drive them to commute for their drug activities. Since the context in which drug use takes place can influence individual-level behaviors, we also explored intra-urban mobility of Tijuana IDUs in relation to risky drug use behaviors.

Methods

Study Population

From February-April 2005, a cross-sectional interviewer-administered survey was conducted among 222 IDUs in Tijuana, as described previously (Brouwer, et al., 2009; Frost et al., 2006). Participants were recruited through respondent-driven sampling (RDS) in order to achieve a more representative sample of this hard-to-reach population (Heckathorn, 1997). Briefly, a group of “seeds” was selected based on diversity of location, gender, and drug preferences, and given three uniquely coded coupons to refer IDUs in their social networks who were themselves given coupons to recruit three peers, until approximately 200 were recruited. Eligibility criteria included being aged 18 years or older, having injected drugs within the previous month, able to speak Spanish or English, and providing informed consent. Although this study was conducted in two cities, Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, the present analysis was restricted to the Tijuana sample, for which detailed neighborhood information was available. The Ethics Board of the Tijuana General Hospital and the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Diego approved all study methods, and informed consent was received from all participants.

Data Collection and Laboratory Testing

Staff from both the Comité Municipal de SIDA (COMUSIDA) [the municipal HIV/AIDS program] and the Centro de Integración y Recuperación para Enfermos de Alcoholismo y Drogadicción “Mario Camacho Espíritu,” A.C. (CIRAD), an NGO that began working with drug users in 1991, administered a quantitative survey to elicit information on topics such as demographic and economic factors, drug use practices, sexual behavior, and HIV testing history. Additionally, participants were asked in which neighborhood (or ‘colonia’) they reside and where they most often injected drugs in the prior 6 months. Tijuana is divided into approximately 700 colonias. These colonias are comprised of roughly 2000 residents each and until recently they were the smallest unit for which public census data were available, making them an appropriate unit for analyses of neighborhood effects (Diez Roux, 2001; Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI), 2000). Whereas new, sparsely populated colonias are largely divided by administrative boundaries, colonias in the most populated areas of the city form neighborhoods with distinct historical traditions and characters. More importantly, colonia names are commonly known and serve as a ready means to determine the approximate locations of residences or injection sites.

Participants were tested in the field for HIV, Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), and syphilis antibodies, as described previously (Frost, et al., 2006). Counseling before testing and upon release of results was provided to all participants. Those testing positive were referred to local public health care providers. Those with syphilis titers 1:8 or greater were provided with free antibiotic treatment and counseling on risk behaviors, while HCV-positives were provided with counseling on risk reduction and medical referrals.

Variable Definitions

Analyses were based on 221 participants who answered the questions: “What is the name of the colonia where you live?” and “In the past 6 months, in which neighborhood did you shoot up the most often?” In a number of cases, colonias identified by participants were sub-divided in the Tijuana census (e.g. Villas del Sol was divided into sections I and II). In these cases, weighting and aggregation of census data was performed. A strength of our mapping strategy was that location information of homeless participants could be collected the same way as for other participants, based on colonia name and landmarks to determine where a participant most often injected or spent their time. As 3 km was close to the median travel distance, distinguished all who lived and injected in the same versus different colonias, was located at a natural break point in the data, and is the distance the average person walks in 30–40 minutes (Knoblauch, Pietrucha, & Nitzburg, 1996; Marx et al., 2000), it was used as the cutoff for distinguishing between injecting “near” versus “far” from one’s residence.

A participant was considered to have participated in distributive syringe or needle sharing if they responded ‘Sometimes,’ ‘Often,’ or ‘Always’ to the question, “In the last 6 months, how often did you give, rent or lend a syringe to someone else that you had already used?” Receptive syringe/needle sharing was based on these same responses to the question, “In the past 6 months, how often have you used a needle or syringe that you knew or suspected had been used before by someone else?” Educational level was divided by secondary education or higher (at least a 9th grade education) vs. less than a secondary education since this is the level to which education is compulsory in Mexico. We defined participants as homeless if in the last 6 months they lived or slept in a car, bus, truck or other vehicle; abandoned building; shelter, welfare residence; on the streets; or in the Tijuana river canal.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (i.e. Chi-square, Fisher’s exact or Mann-Whitney U tests) and univariate logistic regression were used to compare IDUs who lived and most often injected in the same or a nearby colonia compared to those who regularly travelled between colonias for such activities. Respondent Driven Sampling Analysis Tool 6.0.1 was used to explore the structure of the sample and calculate adjusted prevalences, where indicated. The Global Moran's I spatial statistic was calculated to determine the extent of overall clustering of residential and injection colonias, in an effort to see if injection was linked to a certain geographic area(s) rather than a reflection of mobility for other reasons. Characteristics of colonias in which IDUs lived or injected were also compared based on year 2000 census data (INEGI, 2000) or data collected from health service or other registries. In most cases, such analyses were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test to compare median population values. The sample size precluded development of a full multivariate model. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

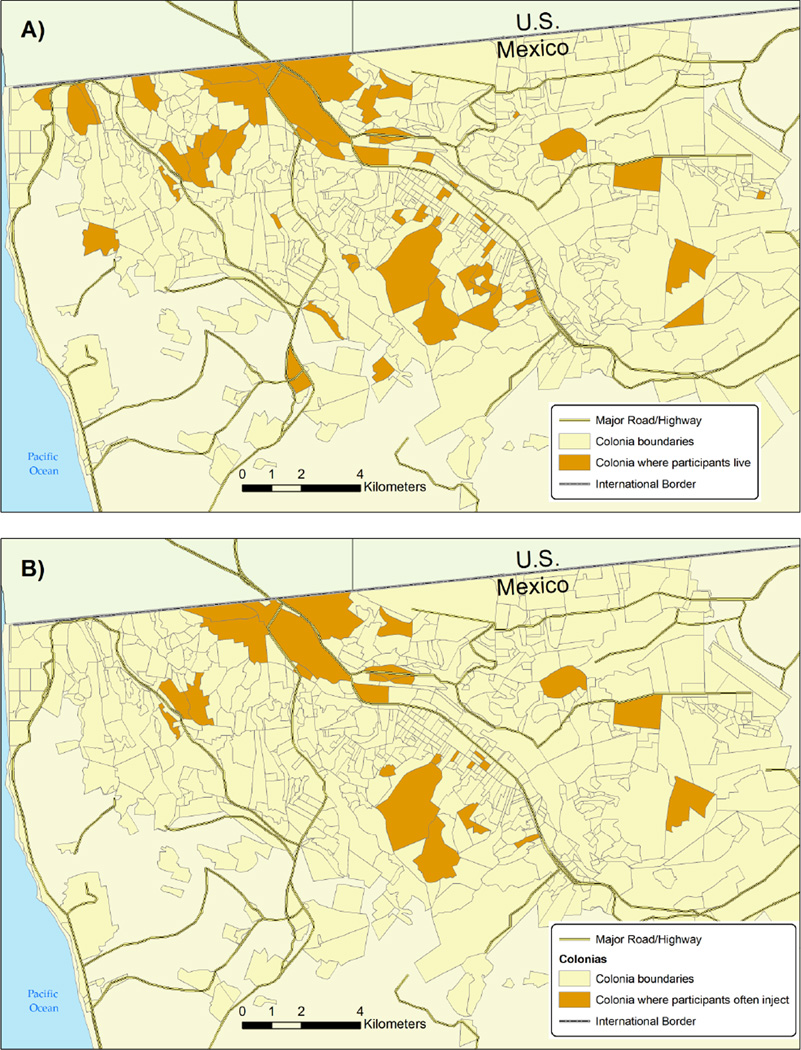

Of the 222 participants enrolled in the study, 221 (99.5%) provided identifiable location information on where they live and most often inject. Of these, 91% were male, median age and age at first injection was 34 and 19 years, respectively; and the majority (57%) was born in southern/central Mexico. Drugs commonly injected in the past 6 months were heroin (98%) and heroin with methamphetamine (67%). Participants resided in 58 identifiable colonias, but regularly injected in only 30 (Figure 1). Neither residential nor injection colonias were particularly clustered (Global Moran’s I p-value>0.1), indicating that participants lived and injected in a variety of locations within the city. For those regularly injecting outside of their colonia of residence, median distance traveled was 3.4 kilometers (inter-quartile range (IQR) 1.9–5.8 km) but ranged as high as 19 km. Approximately a quarter of participants regularly traveled at least 3 km between place of residence and injection. Although adjusted network size was slightly higher for less mobile IDUs (15 vs. 11 for less and more mobile IDUs, respectively) and homophily was somewhat higher for less mobile individuals (0.22 vs. −0.13 for less and more mobile IDUs, respectively), RDS equilibrium was achieved after just two waves.

Figure 1.

Colonia (neighborhood) of residence (panel A) and most frequent injection site (panel B) of injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico (n=221)

More mobile IDUs had a similar age and gender distribution as their less mobile counterparts. Although the groups were similar in percentage currently married, mobile IDUs had nearly 3 times the odds of having had a marriage that had ended in divorce or separation (Table 1). Further, while income levels did not differ greatly, a formal job with pay was the principal source of income for 40% of those injecting farther from their residence versus only 22% for less mobile IDUs. In regards to other mobility variables, those commuting between their injection site and residence had resided longer in Tijuana (p<0.01) and had an increased odds of crossing the Mexico/U.S. border in the past 6 months (p=0.03) (Table 1); however, they were less likely to have lived outside of Mexico in the last 10 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of mobile vs. less mobile IDUs (n=221) *

| Characteristic | More mobile IDUs (n=57) % |

Less mobile IDUs (n=164) % |

Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| % Male | 93.0 | 91.5 | 0.81 | (0.26–2.57) |

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 36.1 ± 8.6 | 34.5 ± 7.6 | ||

| Civil status ‡ | ||||

| Single | 60.0 | 67.9 | ||

| Married/common law | 20.0 | 23.9 | ||

| Divorced/separated | 17.5 | 6.7 | ||

| Widowed | 1.8 | 1.9 | ||

| % Divorced/separated † | 17.5 | 6.7 | 2.96 | (1.18–7.40) |

| Completed secondary school or higher | 24.6 | 35.0 | 0.61 | (0.31–1.20) |

| Job with pay principle source of income in last 6 months † | 40.4 | 22.0 | 2.41 | (1.26–4.59) |

| Earns > 3000 pesos per month § | 34.7 | 41.6 | 0.75 | (0.36–1.53) |

| Homeless (last 6 months) | 56.7 | 52.6 | ||

| Mobility | ||||

| Born outside of the state of Baja California ‡ | 60.7 | 73.5 | 0.56 | (0.28–1.11) |

| Lived in Tijuana at least 10 years † | 80.4 | 59.3 | 2.81 | (1.36–5.84) |

| Worked outside of Mexico in past 10 years † | 24.6 | 45.4 | 0.39 | (0.20–0.77) |

| Crossed border to U.S. (last 6 months) † | 17.9 | 7.6 | 2.63 | (1.07–6.48) |

| Drug Use Activities and Knowledge (last 6 months unless indicated) | ||||

| Age of first injection (mean years ± SD) | 19.7 ± 7.8 | 20.4 ± 6.6 | ||

| Years injecting (mean years ± SD) ‡ | 16.3 ± 9.1 | 14.1 ± 8.2 | ||

| Drugs most frequently used | ||||

| Heroin alone | 38.6 | 30.4 | ||

| Cocaine alone | 0.7 | 0.0 | ||

| Speedball (heroin + cocaine) | 2.1 | 8.7 | ||

| Methamphetamine + Heroin | 53.1 | 52.2 | ||

| Methamphetamine + Cocaine | 1.4 | 2.2 | ||

| Other | 4.2 | 6.5 | ||

| Injects more than once a day ‡ | 64.9 | 51.2 | 1.76 | (0.94–3.29) |

| Distributive syringe/needle sharing†, § | 83.3 | 67.7 | 2.38 | (1.08–5.25) |

| Receptive syringe/needle sharing ‡, § | 85.2 | 74.1 | 2.02 | (0.88–4.63) |

| Injected in any of these places (last 6 months): | ||||

| At home | 29.8 | 36.6 | ||

| At someone else’s home | 28.1 | 23.2 | ||

| Shooting gallery | 75.4 | 67.1 | ||

| Construction site | 19.3 | 17.7 | ||

| Alleyway | 33.3 | 26.2 | ||

| Bar/hangout | 10.5 | 10.4 | ||

| On the street | 42.1 | 39.0 | ||

| Other | 14.0 | 9.8 | ||

| Arrested for carrying new syringes (last month) § | 42.3 | 34.8 | 1.37 | (0.69–2.73) |

| Arrested for carrying used syringes (last month) †, § | 59.3 | 43.2 | 1.93 | (1.28–2.90) |

| Overdose | 13.0 | 6.9 | 2.00 | (0.74–5.46) |

| Identified hepatitis as an infection one can get from drug use † | 17.5 | 37.2 | 0.36 | (0.17–0.76) |

| Identified HIV as an infection you can get from drug use | 76.4 | 83.6 | 0.63 | (0.30–1.34) |

Mobile IDUs were defined as those traveling ≥3 km between residence and injection site; deviations from total N were ≤5 unless indicated

and bold-face. Statistically significant (p<0.05)

Marginally statistically significant (p<0.10); marginal association with years of injecting disappeared upon age adjustment

Total n=198 for income, 212 for distributive and receptive needle sharing, 207 and 209 for arrests for carrying new and used syringes, respectively

SD: Standard Deviation

The two groups were similar in regards to age of first injection, drugs currently used, and the types of places in which injection takes place (e.g. alleyway etc.). However, mobile IDUs had more than twice the odds of engaging in distributive needle sharing (Odds Ratio (OR) 2.38, (95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.08–5.25) and were marginally more likely to engage in receptive needle sharing (OR 2.02, 95%CI: 0.884.63) and inject multiple times per day (OR 1.76, 95%CI: 0.943.29) (Table 1). Mobile IDUs also had almost twice the odds of having been arrested for carrying used syringes during the past month. Mobility was inversely associated with identifying hepatitis as an infection one can acquire from injecting drug use (18% vs. 37%, OR 0.36, 95%CI: 0.17–0.76) and mobile IDUs were somewhat less likely to identify HIV (76% vs. 84%, OR 0.63, 95%CI: 0.30–1.34) as an infection one can acquire from drug use (Table 1).

Crude and RDS-adjusted prevalence of HIV was fairly low overall (3% and 0.6%, respectively) and HCV prevalence was high (96% and 97%, respectively); HIV and HCV serostatus did not differ significantly by mobility. More mobile IDUs, however, were somewhat less likely to test antibody positive for syphilis (Crude and RDS-adjusted (95% CI) prevalence for mobile IDUS 13% and 20% (2%-44%) and less mobile IDUs 15% and 33% (12%-47%)), although the groups did not differ by percentage of cases with high antibody titers (indicative of an active case).

While mobile and less mobile IDUs injected in similar types of neighborhoods, there were distinct differences in the places in which they resided. Less mobile IDUs had higher odds of living in a neighborhood with high levels of drug activity or with a drug treatment center (Table 2). More mobile IDUs tended to live in colonias with a lower percentage of migrants and a higher percentage of home ownership, married residents, and male headed households (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of neighborhoods (colonias) of residence of mobile vs. less mobile IDUs (n=212)

| Colonia characteristic | More mobile IDUs (n=51) |

Less mobile IDUs (n=161) |

P- value* |

Odds Ratio |

95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | |||||

| Colonia considered high drug activity area by police | 63.0 | 79.1 | 0.018 | 0.45 | (0.23–0.88) |

| Health center present | 25.5 | 22.2 | 0.623 | 1.20 | (0.59–2.43) |

| Drug treatment center present | 23.6 | 41.9 | 0.015 | 0.43 | (0.20–0.90) |

| Median % | |||||

| Residents living in Tijuana at least 10 years | 82.2 | 72.7 | <0.001 | ||

| Residents born in the state of Baja California | 41.3 | 35.1 | <0.001 | ||

| Married | 37.2 | 32.1 | <0.001 | ||

| Home ownership | 60.9 | 44.4 | <0.001 | ||

| Female headed households | 23.4 | 27.5 | <0.001 | ||

Based on Pearson chi-square or Mann-Whitney U test

Discussion

While migration has been found to be important in the spread of infectious diseases, comparatively little is known of the effect of intra-urban mobility. Commuting between one’s residence and usual place of injection was common among Tijuana IDUs. The present analysis represents a growing trend in considering spatial aspects of the drug using risk environment. While previous studies tended to use relative distances or approximate travel times to explore associations such as access to care or mobility within a city, mapping technology now allows one to explore such issues in a more systematic manner and in relation to a variety of neighborhood-level data (Brouwer, Weeks, Lozada, & Strathdee, 2008; Latkin, Glass, & Duncan, 1998).

We explored a number of variables that might help to explain some of the intra-urban travel taking place in our study population. It was more common for “more mobile” IDUs to have a job with pay than their less mobile counterparts. As we do not have data on the location of these jobs, we are not able to determine if work outside of one’s residential area explains where a participant most often injects. However, considering that only a minority held a job, this likely is not a primary motivator for living and injecting in different areas. IDUs who most commonly injected far from their residence tended to inject more frequently – although this was not statistically significant. It may be that the extent of their addiction motivates them to inject while away from their home area, while those who use drugs less often can wait until returning home from a drug purchase location. However, when we looked at the types of locations where IDUs injected (e.g. shooting gallery, at a friend’s house, outside, etc.), there were no statistically significant differences between more and less mobile IDUs. While we do not know the exact motivations behind travel, our study did identify some distinct differences between more and less mobile IDUS, which may have important public health consequences. They are discussed in the following.

Needle/syringe sharing was common for the IDUs in the study, but even more so for mobile IDUs. Our findings are supported by a geobehavioral study by Williams and Metzger in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA which found that longer distances between home and places where drugs were used was related to receptive injection equipment sharing by Latino IDUs (C. T. Williams & Metzger, 2010). While it is legal to purchase and carry injection equipment in Mexico, previous qualitative and quantitative studies in this setting have found arrest for carrying clean needles to be common (Pollini et al., 2008; Strathdee et al., 2005). Arrest for possession of unused/sterile syringes was also independently associated with twice the odds of syringe sharing and 3.6 times increased odds of injecting in a shooting gallery, with similar associations found for arrest for carrying used syringes (Philbin et al., 2008; Pollini, et al., 2008). Although more research is needed to understand the reasons for these arrests, they may be related to either police harassment and/or a disconnect between “laws on the books” and enforcement activities (Miller et al., 2008; Pollini, et al., 2008; Strathdee, et al., 2005). Considering that mobile IDUs had nearly twice the odds of having been arrested for carrying a used syringe in the past month, the desire to avoid arrest for carrying needles may have been a motivator behind syringe sharing as well.

Our study suggests that more mobile IDUs may be less likely to know about risks of drug use. Harm reduction services and education in Tijuana – often in the form of mobile clinics - are targeted at drug using hotspots and at the time of the present study, such services were limited in scope; however, if a more “mobile” person is only in these hotspots for a short duration and lives in a neighborhood that is less likely to offer drug treatment, they might not be exposed to education or harm reduction services. If stigma is associated with attending services at fixed sites, moving mobile prevention programs to “sender” colonias will not necessarily result in increased access to information. Instead, qualitative research with mobile IDUs is likely needed to better understand factors shaping their drug use knowledge and behaviors.

We had hypothesized that more mobile IDUs would have higher incomes or reside in neighborhoods with higher socio-economic status, given the cost of intra-urban transportation and perhaps social pressures which may have driven them to commute for their drug activities. Income, however, did not differ between the sub-populations. Whereas higher socio-economic status may characterize some of Tijuana’s commuting population, Klak and Holtzclaw discuss how the poor in Latin American cities scramble for work and shelter wherever they may be found and local policies of enforcement on land invasions may result in long commutes (Klak & Holtzclaw, 1993). Mobile Tijuana IDUs, however, did appear to have more stable financial and living situations, with a higher percentage earning money from a formal job and having lived in Tijuana for a longer period of time.

There were some striking differences between the neighborhoods of residence of more and less mobile IDUs. More mobile IDUs lived in areas with fewer migrants, but higher marriage and home ownership rates. These colonias were also less likely to be considered high drug using/selling areas by the local police. These factors suggest a more stable environment that may perhaps come with increased social pressures against substance use or a lack of social networks of people overtly using drugs, thus driving resident IDUs to travel. Fewer local drug markets, however, may also mean that mobile IDUs are simply traveling to colonias where it is easier to purchase illicit substances.

The differences in injection risk behaviors found in the present study did not translate into statistically significant differences in infectious disease prevalence. This might be attributed in part to our sample size, which gave limited statistical power to find differences in low (HIV) or high prevalence (HCV) infections. Alternatively, the social networks of these two IDU sub-populations may differ, with decreased disease prevalence in networks of more mobile IDUs off-setting higher risk behaviors. However, considering the very high prevalence of HCV in both groups - future spread of HIV, which can increase explosively in IDU populations - should be monitored closely. Further, considering that more mobile IDUs were more likely to have crossed the Mexico/U.S. border in the past 6 months, potential for disease transmission among international networks is concerning. Syphilis antibody prevalence was somewhat higher among less mobile IDUs. This might indicate different sexual networks of each sub-population, especially if mobile IDUs less often engage in sexual relations in the colonias in which they inject.

Our study was limited by mapping participant locations at the neighborhood (polygon) rather than point level. Further, distance calculations were Euclidean, rather than based on actual commute times, which would have yielded greater precision. Despite these limitations, our investigation afforded us with the tools to identify a unique group of “more mobile” IDUs who presented with a different risk profile than less mobile IDUs. The present analysis was also limited in that it focused on the locations where a participant “most often” injected drugs or resided at the time of the interview, whereas such data may be missing stopover points, shifts over time, or other neighborhood environments to which IDUs are exposed. Although mobility patterns are not static, as most of the behavioral data collected referred to the prior 1–6 months, these behaviors likely most often occurred in the mapped locations. Future studies, with longitudinal point data may help to better elucidate differences between IDU sub-populations based on their mobility and the environments in which they live and inject.

We found that mobile IDUs more often engaged in risky injection behaviors and appeared less knowledgeable about blood-borne disease transmission routes than other IDUs, suggesting that current education and harm reduction programs may not be effectively reaching this sub-population, or possibly other contextual variables are at play in enhancing the risk environment. Whereas many cities focus efforts on neighborhoods where injection drug use is most common, these efforts must take into account opportunities to reach those who may not reside in such neighborhoods. Although HIV prevalence was low in the current study, an HIV incidence of 2 per 100 person years was recently found among IDUs and female sex workers in Tijuana (Strathdee & Magis-Rodriguez, 2008), indicating high potential for future transmission. Structural and additional individual-level interventions to reduce sharing of injection equipment are needed. Applying geographic information system methods to future behavioral and intervention IDU studies may provide unique insights to better tailor such efforts in relation to the challenging risk environments which substance users face.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the study participants for their time and willingness to join in this effort. We also extend our thanks to the staff of Proyecto El Cuete, CIRAD, and Patronato ProCOMUSIDA. The authors also express their sincere thanks to the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) for support through grants R37 DA019829, R21 DA024381, and R01 DA09225-S11, donor support for the Harold Simon Chair in Global Public Health, the UCSD Center for AIDS Research (grant P30 AI36214-06), and a career award supporting K.B. (K01DA020364). Special thanks to Carolina Magis, Lourinda Brouwer, and Serena Ruiz for abstract translations.

Glossary

- IDU

Injection Drug User

- GIS

Geographic Information System

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bastos FI, Barcellos C, Lowndes CM, Friedman SR. Co-infection with malaria and HIV in injecting drug users in Brazil: a new challenge to public health? Addiction. 1999;94(8):1165–1174. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94811656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer KC, Case P, Ramos R, Magis-Rodriguez C, Bucardo J, Patterson TL, et al. Trends in Production, Trafficking and Consumption of Methamphetamine and Cocaine in Mexico. Substance Use and Misuse. 2006;41(5):707–727. doi: 10.1080/10826080500411478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer KC, Lozada R, Cornelius WA, Firestone Cruz M, Magis-Rodriguez C, Zuniga de Nuncio ML, et al. Deportation along the U.S.-Mexico border: its relation to drug use patterns and accessing care. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer KC, Weeks JR, Lozada R, Strathdee SA. Integrating GIS into the study of contextual factors affection injection drug use along the Mexico/U.S. border. In: Thomas YF, Richardson D, Cheung I, editors. Geography and Drug Addiction. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bucardo J, Brouwer KC, Magis-Rodriguez C, Ramos R, Fraga M, Perez SG, et al. Historical trends in the production and consumption of illicit drugs in Mexico: implications for the prevention of blood borne infections. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(3):281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehne KL, Khodakevich L, Hamers FF, Schwartlander B. The HIV/AIDS epidemic in eastern Europe: recent patterns and trends and their implications for policy-making. AIDS. 1999;13:741–749. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199905070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–1789. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker E. Epidemic in the war zone: AIDS and community survival in New York City. Int J Health Services. 1990;20:602–615. doi: 10.2190/6M3V-C0G1-AMCJ-6V73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost SD, Brouwer KC, Firestone Cruz MA, Ramos R, Ramos ME, Lozada RM, et al. Respondent-Driven Sampling of Injection Drug Users in Two U.S.-Mexico Border Cities: Recruitment Dynamics and Impact on Estimates of HIV and Syphilis Prevalence. J Urban Health. 2006;83(Suppl 7):83–97. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin SS, Ashford AR, Lantigua R, Hajiani F, Franco R, Heck JE, et al. Intraurban influences on physician colorectal cancer screening practices. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(12):1371–1380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44(2):174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI) XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda 2000. México: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI) Sistema para la consulta de informacion censal. SCINCE por colonias. XII Censo de Poblacion y Vivienda. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI) II Conteo de Población y Vivienda 2005: Principales resultados por localidad 2005 (ITER) 2008 Retrieved from http://www.inegi.gob.mx/est/contenidos/espanol/sistemas/conteo2005/localidad/iter/

- Klak T, Holtzclaw M. The housing, geography, and mobility of Latin American urban poor: the prevailing model and the case of Quito, Ecuador. Growth Change. 1993;24(2):247–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2257.1993.tb00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch RL, Pietrucha MT, Nitzburg M. Field Studies of Pedestrian Walking Speed and Start-Up Time. Transportation Research Record, Pedestrian and Bicycle Research. 1996;1538 [Google Scholar]

- Latkin C, Glass GE, Duncan T. Using geographic information systems to assess spatial patterns of drug use, selection bias and attrition among a sample of injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50(2):167–175. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magis-Rodriguez C, Brouwer KC, Morales S, Gayet C, Lozada R, Ortiz-Mondragon R, et al. HIV prevalence and correlates of receptive needle sharing among injection drug users in the Mexican-U.s. border city of Tijuana. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2005;37(3):333–339. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2005.10400528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx MA, Crape B, Brookmeyer RS, Junge B, Latkin C, Vlahov D, et al. Trends in crime and the introduction of a needle exchange program. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1933–1936. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnochie KM, Russo MJ, McBride JT, Szilagyi PG, Brooks AM, Roghmann KJ. Socioeconomic variation in asthma hospitalization: excess utilization or greater need? Pediatrics. 1999;103(6):e75. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Firestone M, Ramos R, Burris S, Ramos ME, Case P, et al. Injecting drug users' experiences of policing practices in two Mexican-U.S. border cities: public health perspectives. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19(4):324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osypuk TL, Acevedo-Garcia D. Are racial disparities in preterm birth larger in hypersegregated areas? Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(11):1295–1304. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periódico Oficial del Estado de Baja California. Ley Orgánica de la Administración Pública Municipal. Baja California: Mexicali; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Philbin M, Pollini RA, Ramos R, Lozada R, Brouwer KC, Ramos ME, et al. Shooting gallery attendance among IDUs in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico: correlates, prevention opportunities, and the role of the environment. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(4):552–560. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9372-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollini RA, Brouwer KC, Lozada RM, Ramos R, Cruz MF, Magis-Rodriguez C, et al. Syringe possession arrests are associated with receptive syringe sharing in two Mexico-US border cities. Addiction. 2008;103(1):101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlis B, Brouwer KC, Mills EJ, Hayes M, Kerr T, Hogg RS. Migration and transmission of blood-borne infections among injection drug users: understanding the epidemiologic bridge. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(2–3):107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell R, Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Perlis TE, Paone D. Geographic proximity, policy and utilization of syringe exchange programmes. AIDS Care. 1999;11(4):437–442. doi: 10.1080/09540129947811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) All Crossings at California's Ports of Entry. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.sandag.org/uploads/publicationid/publicationid_895_4055.pdf.

- Sarang A, Rhodes T, Platt L. Access to syringes in three Russian cities: implications for syringe distribution and coverage. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19(Suppl 1):S25–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Fraga WD, Case P, Firestone M, Brouwer KC, Perez SG, et al. “Vivo para consumirla y la consumo para vivir” [“I live to inject and inject to live”]: High-Risk Injection Behaviors in Tijuana, Mexico. J Urban Health. 2005;(82) 3_suppl_4:iv58–iv73. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Magis-Rodriguez C. Mexico's evolving HIV epidemic. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(5):571–573. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trillo A. Adictos: enfermos pero no criminales [Addicts: sick but not criminals] Border Reflections. 2002 Retrieved February 17, 2008, from http://www.pciborderregion.com/newsletter/1700_SP/1700_1_EN.htm.

- United Nations Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2007 Revision. New York: United Nations; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Uriely N, Belhassen Y. Drugs and tourists' experiences. J Travel Res. 2005;43:238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Williams CT, Metzger DS. Race and distance effects on regular syringe exchange program use and injection risks: A geobehavioral analysis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1068–1074. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, Atkinson J, Klovdahl A, Ross MW, Timpson S. Spatial bridging in a network of drug-using male sex workers. J Urban Health. 2005;82(Suppl 1):i35–i42. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]