Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to develop a cell culture system for fetal baboon hepatocytes and to test the hypotheses that (1) expression of the gluconeogenic enzyme phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase-1 (PEPCK-1) is upregulated in hepatocytes isolated from fetuses of nutrient-restricted mothers (MNR) compared to ad libitum-fed controls (CTR) and (2) glucocorticoids stimulate PEPCK-1 expression.

Methods

Hepatocytes from 0.9G CTR and MNR fetuses were isolated and cultured. PEPCK-1 protein and mRNA levels in hepatocytes were determined by western blot and quantitative PCR, respectively.

Results

Fetuses of MNR mothers were intrauterine growth restricted (IUGR). Feasibility of culturing 0.9G fetal baboon hepatocytes was demonstrated. PEPCK-1 protein levels were increased in hepatocytes isolated from IUGR fetuses and PEPCK-1 mRNA expression was stimulated by glucocorticoids in fetal hepatocytes.

Conclusions

Cultured fetal baboon hepatocytes that retain their in vivo phenotype provide powerful in vitro tools to investigate mechanisms that regulate normal and programmed hepatic function.

Keywords: Liver, dexamethasone, diabetes nonhuman primate

Introduction

Compromised intrauterine environment, such as restricted nutrient availability, has a profound impact on health and disease later in life (20, 37, 53). This concept, referred to as developmental programming, can be defined as the response to a specific challenge during a critical developmental time window that alters the trajectory of development, altering phenotype and predisposing to chronic adult diseases. Human epidemiological studies have shown that unwanted effects of altered development including those resulting in mild growth restriction may predispose to chronic adult diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease (37). These human studies provided the stimulus for extensive animal studies interrogating the underlying mechanisms whereby reduced maternal nutrient availability results in predisposition to chronic adult diseases (3, 4).

Across a wide variety of species, immediate prenatal organ terminal differentiation is dependent on fetal glucocorticoids (15). This key developmental function of glucocorticoids has been shown most clearly in studies utilizing the unique capability to catheterize blood vessels in both the pregnant ewe and her fetus and carry out perturbation studies in which fetal adrenal function is either decreased (by adrenalectomy) or increased by administration of physiological or supraphysiological amounts of glucocorticoid. In these studies glucocorticoids have been shown to regulate late gestation maturation of the fetal thyroid (56), brain (11), kidney (24, 25), liver (13, 34), pancreas (14), gut (57), skeletal muscle (17), lung (32), and heart and cardiovascular system (58).

Evidence for this important role for fetal glucocorticoids in nonhuman primates however is more difficult to obtain due to the difficulty in conducting required chronic fetal catheterization studies in these species. The ability of maternal treatment with synthetic glucocorticoids to accelerate fetal lung maturation in primates, both humans and experimental nonhuman primate models would indicate that similarities exist between primates and other precocial species (6, 21, 22, 30, 31, 35). To remove this barrier to progress and enable studies on metabolism in the fetal nonhuman primate we have developed a model of baboon pregnancy for the study of the effects of maternal nutrition reduction on fetal development (49, 50, 52). Studies in this model have demonstrated that maternal consumption of 70% of the global ad libitum diet fed from 0.16 gestation (G, 30 days of gestation - G) to 0.9G (165 days G; full term is 180 days G) of pregnancy leads to altered function of the placenta (28) and several fetal organs by 0.9G - kidney, adipose tissue, brain (2, 8, 9, 39, 40, 55) as well as the liver (18, 23). Importantly, offspring of MNR mothers show an altered postnatal behavioral phenotype (45) and the emergence of a pre-diabetic state by puberty (7).

In this paper we report our finding that both male and female fetuses of MNR mothers are IUGR and weigh less than CTR fetuses. We also demonstrate the development of a system to study the key gluconeogenic enzyme PEPCK-1 and test the hypothesis that glucocorticoids enhance fetal hepatocyte PEPCK-1 expression using cultured 0.9G fetal baboon hepatocytes. We have previously shown that PEPCK-1 expression is elevated in vivo at 0.9G in the fetal liver in the setting of MNR, a situation in which fetal cortisol is also elevated (39).

Materials and Methods

Animal Care and Maintenance

The research conducted herein was approved by the Texas Biomedical Research Institute and University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

We studied a total of 38 baboon pregnancies. Details of housing structure, system for recording individual feeding, and formation of stable grouping for the nutrient reduction study have been previously published in detail (8, 48). The individual feeding system used in this study allows group social interaction and normal physical activity while permitting individual feeding. Maternal morphometric measurements were made prior to pregnancy to ensure homogeneity of weight and general morphometrics (8, 48).

Diet and food consumption

Baboons ate Purina Monkey Diet 5038 with a basic composition of crude protein not less than 15%, crude fat not less than 5%, crude fiber not more than 6%, ash not more than 5% and added minerals not more than 3% throughout the study. All pregnant baboons were fed ad libitum until 30 days of gestation when CTR baboons continued to feed ad libitum and MNR baboons were fed 70% of feed consumed by CTR on a weight adjusted basis (8).

Cesarean sections and tissue collection

Cesarean sections were performed at 165 days G [0.9G; fetuses of CTR mothers, N=24 (11 males, 13 females); fetuses of MNR mothers, N=14 (8 males, 6 females)] under isoflurane anesthesia (2%, 2 l/min) to obtain the fetus. Techniques used and post-operative maintenance have been previously described in detail (51). Analgesia was provided with Buprenorphine hydrochloride 0.015 mg.kg-1.d-1 during 3 postoperative days [Buprenex ® Injectable, Reckitt Benckiser Health care (UK) Ltd, Hull, England HU8 7DS]. The fetus was submitted for morphometric measurements and tissue sampling. Fetal livers were rapidly removed and either processed for hepatocyte isolation (as described below) or cut into pieces and quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen before the fetus was euthanized by exsanguination while still under general anesthesia.

Isolation of hepatocytes

Hepatocytes were isolated from 0.9G fetuses [fetuses of CTR mothers, N=6 (5 males, 1 female); fetuses of MNR mothers, N=6 (4 males, 2 females)] by following a modified protocol used to isolate fetal rat hepatocytes (33). Briefly, baboon fetal liver tissues were finely minced and incubated at 37°C in calcium-free Earles Balanced Salt Solution (EBSS), pH 7.4 for 5 min, followed by three 15 min-incubations at 37°C in calcium-free EBSS containing 0.05% collagenase (Type II) and 0.005% DNase I, pH 7.4. The media was gassed (95% O2-5%CO2) for 15 sec before incubation. After each 15 min-incubation, supernatent was collected, added to Williams E medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and filtered through a 0.45 micron nylon mesh. Isolated hepatocytes were then resuspended in Williams E media following passage through 90% percoll and three low-speed centrifugations (50g/4°C/2 min). Trypan blue dye exclusion was then performed to determine cell viability and yield, and monitor uniformity between preparations. Fetal baboon hepatocytes with a viability >90% were routinely cultured and used in our studies.

Culture of hepatocytes

Freshly isolated hepatocytes were suspended in Williams E medium containing 1% glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 5% FBS, and plated on collagen-coated dishes at a density of 40X104 cells/35 mm dish or 15X104 cells/well in a 24-well dish. To perform immunocytochemistry, 15X104 cells were plated on collagen-coated coverslips. Two h after incubation at 37°C, the cells were washed and incubated overnight in fresh Williams E medium containing 5% FBS. The next day, cells were incubated in serum-free Williams E medium for 8 h. Hepatocytes were then cultured in the absence or presence of dexamethasone (100 nM) for an additional 24 h prior to study.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from hepatocytes using TRI Reagent according to manufacturer's instructions. The RNA samples were treated with DNAse I (RNAse-free) and then reverse transcribed. The complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was carried out in a thermocycler at 25°C/10 min, 42°C/50 min, 72°C/10 min and 4°C. Real time RT-PCR assay was then performed with the TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, CA) for human PEPCK-1 (Hs01552565_g1) using an ABI 7700 Sequence Detection System. In each experiment mRNA levels were normalized to 18S RNA (TaqMan Gene Expression Assay Hs99999901_s1) which did not change under experimental conditions (data not shown).

Western blot analysis

Cells plated on collagen-coated dishes were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Cell lysates were rocked at 4°C for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 10,000g for 2 min at 4°C. The supernatant proteins were estimated by bincinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Protein samples (10 μg) were added to 4X sample buffer (150 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 1% SDS, 40% glycerol), size-fractionated on 8% SDS polyacrylamide gels, and electroblotted onto 0.45 μm PVDF membranes. Membranes were immunoblotted overnight at 4°C with specific PEPCK-1 (1:250, #28455, Abcam, MA), albumin (1:250, #sc-46293, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (HNF4α, 1:250, #417700, Invitrogen, NY), alpha feto protein (AFP, 1:250, #sc-130302, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) or tubulin (1:1000; loading control, #1799-1, Epitomics, CA) primary antibodies followed by a secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody [(1:10,000 dilution, anti-rabbit #111-036-046 or anti-mouse #115-036-071; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, PA) for 1 hr at room temperature. Specific proteins were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (GE Healthcare Biosciences, PA). Immunoblots were quantified with Scion Image analysis software (Scion Corporation, MD). For detection of secreted insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), conditioned medium was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 mins, and equal volumes of supernatant was then mixed with 4× sample buffer followed by size fractionation of proteins on 12% SDS polyacrylamide gel. Immunoblot analysis was performed using wet transfer and membranes blocked using 5% bovine serum albumin. IGFBP-1 monoclonal antibody (1:10000, #6303-SP-5, Medix Biochemica, Finland) was used as the primary antibody and HRP conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000, #170-6515, BioRad, CA) as the secondary antibody. Western Lighting Enhanced Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer, MA) was used for detection of proteins. The image was captured using Quantity One imaging software (BioRad, CA).

Immunocytochemical staining of cells

After 24-48 h of culture, cells on coverslips were rinsed with PBS and then fixed in 10% formalin for 30 min. Coverslips were then washed with PBS followed by treatment with blocking buffer (1.5% normal serum with 0.1% triton X-100, 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS) for 10 min. FX signal enhancer (#136933, Invitrogen, NY) was added for 30 min. Next, the cells were incubated with primary antibody PEPCK-1 (1:50, #28455, Abcam, MA) and HNF4α (1:25, #417700, Invitrogen, NY) overnight at 4°C. The next morning, after repeated washes with PBS, the coverslips were incubated with secondary antibodies (1:500), either goat anti-rabbit (#A11012, Invitrogen, NY) or goat anti-mouse (#A31619, Invitrogen, NY) in blocking buffer for 60 mins at room temperature in the dark. The coverslips were rinsed and then mounted (50% glycerol in 10mM Tris-HCl pH8.0) and sealed on glass slides with clear nail polish. Slides were stored at 4°C and protected from light until images were taken. Images were acquired with a SPOT cooled camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., MI).

Statistical analysis

To determine the effects of treatment on fetal weight, an initial comparison of male and female fetuses was first performed. As expected this comparison by t-test showed that the male and female fetuses were two distinct groups and thus analysis of the effect of the dietary treatment on fetal weights in the two sexes was conducted separately by t-test. Fetal hepatic protein levels acquired by Western blot analysis and mRNA levels obtained by quantitative RT-PCR were compared between CTR and IUGR fetuses and untreated (con) and dexamethasone (Dex)-treated groups using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Results for males and female fetuses were pooled together for studies performed in hepatocytes as the distribution of sexes did not permit a comparison by sex of fetus. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant and SAS version 9.3 software (The SAS Institute, NC) was used for analyses.

Results

At necropsy female CTR fetuses weighed 757.0 ± SD 30.0g (N=13) and fetuses of MNR mothers weighed 670.8 ± SD 26.0g (N=6) (P<0.05); male CTR fetuses weighed 840.4 ± SD 33.6g (N=11), and fetuses of MNR mothers weighed 748.8 ± SD 26.5g (N=8) (P<0.05). Thus both males and female fetuses of MNR mothers were intrauterine growth restricted (IUGR).

Fetal baboon hepatocytes in culture express hepatocyte markers

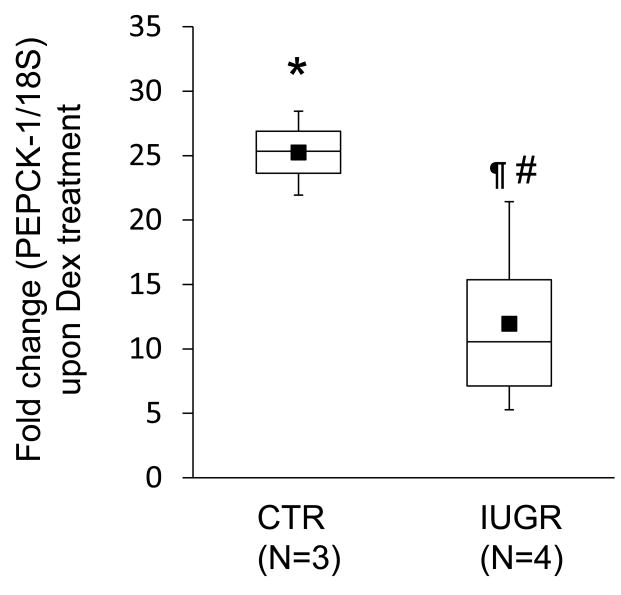

As shown in Fig 1A, hepatocytes isolated from 0.9G fetuses expressed a number of well-established hepatocyte marker proteins including albumin, PEPCK-1, AFP and HNF4α. Cultured 0.9G cells also secreted the hepatocyte marker insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1), an important IGF binding protein involved in fetal growth and development (1, 54). Additionally, we performed immunofluorescence studies which demonstrated the cellular co-localization of cytosolic PEPCK-1 and nuclear HNF4α in 0.9G hepatocytes cultured on collagen-coated coverslips (Fig 1B).

Figure 1. Expression of hepatocyte markers in 0.9G baboon hepatocytes.

A) Western blot analysis demonstrating expression of well-established hepatocyte markers, albumin, PEPCK-1, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α) and alpha feto protein (AFP), in hepatocytes isolated from 0.9G fetal liver. Presence of secreted insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) in the media is also observed. B) Immunohistochemistry indicating the presence of cytosolic PEPCK-1 and nuclear HNF4α in hepatocytes isolated from a 0.9G fetus.

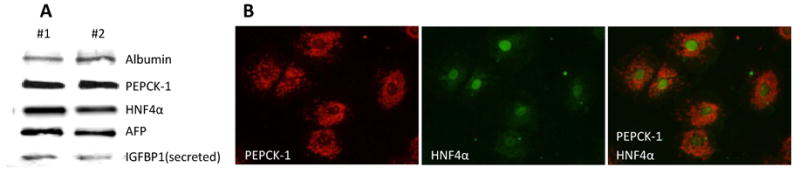

PEPCK-1 expression is increased in 0.9G IUGR fetal hepatocytes

We have previously observed that MNR increases in vivo PEPCK-1 expression in 0.9G fetal liver tissues (39). To determine whether there is a similar increase in PEPCK-1 expression in cultured 0.9G IUGR hepatocytes, we compared PEPCK-1 protein levels in hepatocytes isolated from 0.9G IUGR and CTR fetuses. As shown in Fig 2, western blot analysis demonstrated ∼4-fold increase (X2=3.76, df=1, P=0.05) in PEPCK-1 protein levels in 0.9G IUGR fetal hepatocytes compared to 0.9G CTRs.

Figure 2. PEPCK-1 protein levels are increased in 0.9G baboon hepatocytes isolated from IUGR fetuses.

Box-and-whisker plot for CTR (N=3) and IUGR (N=5) are shown. The lower boundary of the box-and-whisker plot corresponds to the 25th percentile, the line within the box to the median, and the upper boundary of the box to the 75th percentile. Mean (■); * (X2=3.76, df=1, P=0.05). Inset shows representative immunoblots from 2 CTR and IUGR fetuses. Tubulin was used as a loading control.

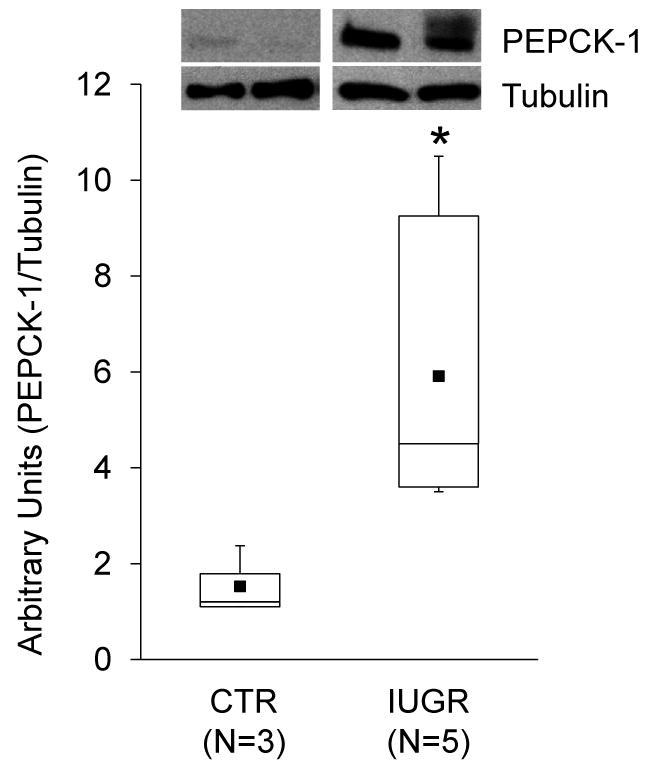

Dexamethasone (Dex) stimulation of PEPCK-1 expression in 0.9G fetal hepatocytes

To determine whether direct exposure of fetal IUGR liver hepatocytes to increased glucocorticoid levels augments PEPCK-1 expression, 0.9G CTR and IUGR fetal hepatocytes were cultured for 24 h followed by exposure to 100 nM Dex, a synthetic glucocorticoid, for another 24 h. As shown in Fig 3, Dex treatment of 0.9G CTR fetal hepatocytes resulted in ∼25-fold increase (X2=4.35, df=1, P<0.04) in PEPCK-1 mRNA levels, as measured by quantitative RT-PCR. Treatment of 0.9G IUGR fetal hepatocytes with Dex demonstrated a smaller but highly significant ∼12-fold (X2=6.05, df=1, P<0.02) increase in PEPCK-1 expression. The increase in PEPCK-1 mRNA levels in Dex-treated cells isolated from CTR fetuses was significantly greater (X2=4.5, df=1, P<0.04) than the observed increase in Dex-treated IUGR hepatocytes.

Figure 3. Dexamethasone treatment of hepatocytes from 0.9G CTR and IUGR fetuses increases PEPCK-1 mRNA levels.

Box-and-whisker plots depict fold change in PEPCK-1 mRNA levels upon Dex (100 nM) treatment of hepatocytes for 24 h compared to untreated cells. The lower boundary of the box-and-whisker plot corresponds to the 25th percentile, the line within the box to the median, and the upper boundary of the box to the 75th percentile. CTR (N=3, paired); IUGR (N=4, paired); Mean (■); * (X2=4.35, df=1, P<0.04) for Dex-treated vs untreated CTR samples; ¶ (X2=6.05, df=1, P<0.02) for Dex-treated vs untreated IUGR samples; # (X2=4.5, df=1, P<0.04) for CTR vs IUGR Dex-treated samples.

Discussion

We have developed and characterized a nonhuman primate baboon model of MNR (7, 23, 28, 39, 40, 47) which shows elevated circulating fetal glucocorticoids and expression of the key hepatic gluconeogenic enzyme PEPCK-1. In this study we report that the moderate level of MNR produces IUGR fetuses. To determine potential cellular mechanisms involved in the increased hepatic expression of PEPCK-1 in the IUGR fetuses in vivo, we isolated fetal hepatocytes at 0.9G since this time represents maximum fetal maturation without complication by changes in labor. To our knowledge, fetal nonhuman primate hepatocytes have never been cultured previously. We examined the expression of several hepatic proteins by immunocytochemistry and western blot analysis to determine whether the cultured cells had functional properties of hepatocytes (Fig 1). AFP and albumin, the earliest markers to be expressed by the embryonic liver (61) were expressed in the cultured cells as demonstrated by western blot analysis. Hepatocytes also expressed HNF4α, a nuclear transcription factor that is crucial for hepatocyte differentiation and function (61). Furthermore, the cultured hepatocytes secreted IGFBP-1, an important signaling molecule of the IGF axis, which plays a critical role in fetal growth and development (1, 54). In additional studies, we observed elevated PEPCK-1 protein expression in cultured hepatocytes from 0.9G IUGR fetuses compared to CTR fetuses (Fig 2), as previously observed in vivo at term (39). Taken together, these studies demonstrate that the cultured cells have functional properties of hepatocytes and are suitable to study early, causative mechanisms involved in upregulation of PEPCK-1 – and potentially other cellular mechanisms in IUGR fetuses.

Transcriptional activation of PEPCK-1 has been extensively investigated. Glucocorticoids play an important role in increasing PEPCK-1 expression (19, 60). In addition, glucocorticoids induce numerous enzymes and mediate liver glycogen accumulation at the end of pregnancy to prepare the fetus for independent neonatal life (29). However, increased fetal glucocorticoid exposure impairs growth, promotes gluconeogenesis, and antagonizes insulin's actions (10, 59). Research in rodents and ruminants has shown an increase in circulating glucocorticoid levels in fetuses of nutrient-restricted mothers (3, 5). Studies have also shown that prenatal exposure to dexamethasone increases PEPCK-1 resulting in hyperglycemia in adult rat offspring (41). In the current study, we observed that exposure of hepatocytes from both CTR and IUGR fetuses increases PEPCK-1 expression significantly (Fig 3). Although the IUGR fetal hepatocytes demonstrate an increase in PEPCK-1 expression upon Dex treatment, the fold increase is significantly lower than that observed with the CTR fetal hepatocytes perhaps because of prior in vivo exposure to cortisol. Our results thus suggest that the in vivo increase in hepatic PEPCK-1 expression observed in our nonhuman primate IUGR model may be due to increased fetal cortisol levels.

Animal studies have at least three major strengths over human fetal studies: 1) better control of maternal variables, 2) relevant data obtained more rapidly and 3) insight into mechanisms responsible for observed effects due to the ability to obtain fetal tissue samples across gestation in ways not ethical in human pregnancy. The baboon is the nonhuman primate species with the greatest amount of experimental data on placental and fetal metabolic and endocrine development (26, 36, 42). Genetic similarity between baboons and humans is evident in overall DNA and individual gene sequence identity (98%) and arrangement of genetic loci on chromosomes (43, 44, 46) reflecting a close evolutionary relationship. Our baboon model of IUGR (7, 23, 28, 39, 40, 47) which shows the emergence of a pre-diabetic state in juveniles provides an opportunity for understanding mechanisms mediating the long lasting effects of environmental exposures during gestation on the emergence of late onset adult diseases like type 2 diabetes (12, 16, 27, 38).

In summary, we have shown that 30% global MNR results in fetal IUGR. We have demonstrated the feasibility of culturing primary hepatocytes from fetal baboons at 0.9G and that the cells maintain their in vivo phenotype when cultured. Our studies also show that fetal baboon hepatocytes in culture respond to glucocorticoids by increasing key gluconeogenic enzyme PEPCK-1 expression. Thus, our cell culture system provides a unique opportunity to elucidate mechanisms potentially involved in fetal programming of liver function. We speculate that upregulation of hepatic PEPCK-1 by elevated fetal cortisol in IUGR fetuses results in increased gluconeogenesis, which could contribute to diabetes in later life.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge grant support from NIH grant HD 21350 (PWN), Grant-in-Aid American Heart Association Award (AK), Kronos Longevity Research Institute grant (AK) and CTSA grant UL1RR025767 (AK).

References

- 1.Abu Shehab M, Khosravi J, Han VKM, et al. Site-specific IGFBP-1 hyper-phosphorylation in fetal growth restriction: clinical and functional relence. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:1873–1881. doi: 10.1021/pr900987n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonow-Schlorke I, Schwab M, Cox LA, et al. Vulnerability of the fetal primate brain to moderate reduction in maternal global nutrient availability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3011–3016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009838108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armitage JA, Khan IY, Taylor PD, et al. Developmental programming of the metabolic syndrome by maternal nutritional imbalance: how strong is the evidence from experimental models in mammals? J Physiol. 2004;561:355–377. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.072009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armitage JA, Poston L, Taylor PD. Developmental origins of obesity and the metabolic syndrome: the role of maternal obesity. Front Horm Res. 2008;36:73–84. doi: 10.1159/000115355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armitage JA, Taylor PD, Poston L. Experimental models of developmental programming: consequences of exposure to an energy rich diet during development. J Physiol. 2005;565:3–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck JC, Mitzner W, Johnson JW, et al. Betamethasone and the rhesus fetus: effect on lung morphometry and connective tissue. Pediatr Res. 1981;15:235–240. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198103000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi J, Li C, McDonald TJ, et al. Emergence of insulin resistance in juvenile baboon offspring of mothers exposed to moderate maternal nutrient reduction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R757–R762. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00051.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox LA, Nijland MJ, Gilbert JS, et al. Effect of 30 per cent maternal nutrient restriction from 0.16 to 0.5 gestation on fetal baboon kidney gene expression. J Physiol. 2006;572:67–85. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox LA, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N, Hubbard GB, et al. Gene expression profile differences in left and right liver lobes from mid-gestation fetal baboons: a cautionary tale. The Journal of Physiology Online. 2006;572:59–66. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.105726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dean S, Tang JI, Seckl JR, Nyirenda MJ. Developmental and tissue-specific regulation of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-alpha (HNF4-alpha) isoforms in rodents. Gene Expr. 2010;14:337–344. doi: 10.3727/105221610x12717040569901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan AR, Sadowska GB, Stonestreet BS. Ontogeny and the effects of exogenous and endogenous glucocorticoids on tight junction protein expression in ovine cerebral cortices. Brain Res. 2009;1303:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards LJ, Coulter CL, Symonds ME, McMillen IC. Prenatal undernutrition, glucocorticoids and the programming of adult hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28:938–941. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowden AL, Forhead AJ. Adrenal glands are essential for activation of glucogenesis during undernutrition in fetal sheep near term. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E94–102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00205.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowden AL, Gardner DS, Ousey JC, et al. Maturation of pancreatic beta-cell function in the fetal horse during late gestation. J Endocrinol. 2005;186:467–473. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowden AL, Giussani DA, Forhead AJ. Intrauterine programming of physiological systems: causes and consequences. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:29–37. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00050.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gnanalingham MG, Mostyn A, Symonds ME, Stephenson T. Ontogeny and nutritional programming of adiposity in sheep: potential role of glucocorticoid action and uncoupling protein-2. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1407–R1415. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00375.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gokulakrishnan G, Estrada IJ, Sosa HA, Fiorotto ML. In utero glucocorticoid exposure reduces fetal skeletal muscle mass in rats independent of effects on maternal nutrition. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R1143–R1152. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00466.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo C, Li C, Myatt L, et al. Sexually Dimorphic Effects of Maternal Nutrient Reduction on Expression of Genes Regulating Cortisol Metabolism in Fetal Baboon Adipose and Liver Tissues. Diabetes. 2012 doi: 10.2337/db12-0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanson RW, Reshef L. Regulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) gene expression. Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:581–611. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoet JJ, Ozanne S, Reusens B. Influences of pre- and postnatal nutritional exposures on vascular/endocrine systems in animals. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 3):563–568. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson JW, Mitzner W, London WT, et al. Betamethasone and the rhesus fetus: multisystemic effects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;133:677–684. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson JW, Mitzner W, London WT, et al. Glucocorticoids and the rhesus fetal lung. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978;130:905–916. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(78)90267-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamat A, Nijland MJ, McDonald TJ, et al. Moderate global reduction in maternal nutrition has differential stage of gestation specific effects on {beta}1- and {beta}2-adrenergic receptors in the fetal baboon liver. Reprod Sci. 2011;18:398–405. doi: 10.1177/1933719110386496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller-Wood M, von Reitzenstein M, McCartney J. Is the fetal lung a mineralocorticoid receptor target organ? Induction of cortisol-regulated genes in the ovine fetal lung, kidney and small intestine. Neonatology. 2009;95:47–60. doi: 10.1159/000151755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim CR, Sadowska GB, Newton SA, et al. Na+,K+-ATPase activity and subunit protein expression: ontogeny and effects of exogenous and endogenous steroids on the cerebral cortex and renal cortex of sheep. Reprod Sci. 2011;18:359–373. doi: 10.1177/1933719110385137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koenen SV, Mecenas CA, Smith GS, et al. Effects of maternal betamethasone administration on fetal and maternal blood pressure and heart rate in the baboon at 0.7 of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:812–817. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langley-Evans SC. Nutritional programming of disease: unravelling the mechanism. J Anat. 2009;215:36–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, et al. Effects of maternal global nutrient restriction on fetal baboon hepatic insulin-like growth factor system genes and gene products. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4634–4642. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liggins GC. The role of cortisol in preparing the fetus for birth. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1994;6:141–150. doi: 10.1071/rd9940141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liggins GC, Howie RN. A controlled trial of antepartum glucocorticoid treatment for prevention of the respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants. Pediatrics. 1972;50:515–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liggins GC, Kitterman JA. Development of the fetal lung. Ciba Found Symp. 1981;86:308–330. doi: 10.1002/9780470720684.ch15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liggins GC, Kitterman JA, Campos GA, et al. Pulmonary maturation in the hypophysectomised ovine fetus. Differential responses to adrenocorticotrophin and cortisol. J Dev Physiol. 1981;3:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lilja H, Arkadopoulos N, Blanc P, et al. Fetal rat hepatocytes: isolation, characterization, and transplantation in the Nagase analbuminemic rats. Transplantation. 1997;64:1240–1248. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199711150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNeil CJ, Nwagwu MO, Finch AM, et al. Glucocorticoid exposure and tissue gene expression of 11beta HSD-1, 11beta HSD-2, and glucocorticoid receptor in a porcine model of differential fetal growth. Reproduction. 2007;133:653–661. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitzner W, Johnson JW, Scott R, et al. Effect of betamethasone on pressure-volume relationship of fetal rhesus monkey lung. J Appl Physiol. 1979;47:377–382. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.47.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Musicki B, Pepe GJ, Albrecht ED. Functional differentiation of the placental syncytiotrophoblast: Effect of estrogen on chorionic somatomammotropin expression during early primate pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4316–4323. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-022052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nathanielsz PW. Life in the Womb: The Origin of Health and Disease. Ithaca, NY: Promethean Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nathanielsz PW. Animal models that elucidate basic principles of the developmental origins of adult diseases. ILAR J. 2006;47:73–82. doi: 10.1093/ilar.47.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nijland MJ, Mitsuya K, Li C, et al. Epigenetic modification of fetal baboon hepatic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase following exposure to moderately reduced nutrient availability. J Physiol. 2010;588:1349–1359. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.184168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nijland MJ, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, et al. Non-human primate fetal kidney transcriptome analysis indicates mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a central nutrient-responsive pathway. J Physiol. 2007;579:643–656. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.122101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nyirenda MJ, Lindsay RS, Kenyon CJ, et al. Glucocorticoid exposure in late gestation permanently programs rat hepatic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucocorticoid receptor expression and causes glucose intolerance in adult offspring. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2174–2181. doi: 10.1172/JCI1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pepe GJ, Albrecht ED. Fetal regulation of transplacental cortisol-cortisone metabolism in the baboon. Endocrinology. 1987;120:2529–2533. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-6-2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perelygin AA, Kammerer CM, Stowell NC, Rogers J. Conservation of human chromosome 18 in baboons (Papio hamadryas): a linkage map of eight human microsatellites. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;75:207–209. doi: 10.1159/000134484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powell JR, Caccone A. Intraspecific and interspecific genetic variation in Drosophila. Genome. 1989;31:233–238. doi: 10.1139/g89-040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodriguez JS, Bartlett TQ, Keenan KE, et al. Sex Dependent Cognitive Performance in Offspring Baboons Following Maternal Caloric Restriction in Pregnancy and Lactation. Reproductive Sciences. doi: 10.1177/1933719111424439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogers J, Mahaney MC, Witte SM, et al. A genetic linkage map of the baboon (Papio hamadryas) genome based on human microsatellite polymorphisms. Genomics. 2000;67:237–247. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N, Ballesteros B, Dudley C, et al. Moderate maternal nutrient restriction, but not glucocorticoid administration, leads to placental morphological changes in the baboon (Papio sp.) Placenta. 2007;28:783–793. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Howell K, Rice K, et al. Development of a system for individual feeding of baboons maintained in an outdoor group social environment. J Med Primatol. 2004;33:117–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Howell K, Rice K, et al. Development of a system for individual feeding of baboons maintained in an outdoor group social environment. J Med Primatol. 2004;33:117–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, Dammann MJ, et al. Normal concentrations of essential and toxic elements in pregnant baboon and fetuses (Papio species) J Med Primatol. 2004;33:152–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, Dammann MJ, et al. Normal concentrations of essential and toxic elements in pregnant baboons and fetuses (Papio species) J Med Primatol. 2004;33:152–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2004.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlabritz-Loutsevitch NE, Hubbard GB, Jenkins SL, et al. Ontogeny of hematological cell and biochemical profiles in maternal and fetal baboons (Papio species) J Med Primatol. 2005;34:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2005.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Symonds ME, Sebert SP, Budge H. The impact of diet during early life and its contribution to later disease: critical checkpoints in development and their long-term consequences for metabolic health. Proc Nutr Soc. 2009;68:416–421. doi: 10.1017/S0029665109990152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tazuke SI, Mazure NM, Sugawara J, et al. Hypoxia stimulates insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 (IGFBP-1) gene expression in HepG2 cells: a possible model for IGFBP-1 expression in fetal hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10188–10193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tchoukalova YD, Nathanielsz PW, Conover CA, et al. Regional variation in adipogenesis and IGF regulatory proteins in the fetal baboon. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;380:679–683. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas AL, Krane EJ, Nathanielsz PW. Changes in the fetal thyroid axis after induction of premature parturition by low dose continuous intravascular cortisol infusion to the fetal sheep at 130 days of gestation. Endocrinology. 1978;103:17–23. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trahair JF, Perry RA, Silver M, Robinson PM. Studies on the maturation of the small intestine in the fetal sheep. II The effects of exogenous cortisol Q J Exp Physiol. 1987;72:71–79. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1987.sp003056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Unno N, Wong CH, Jenkins SL, et al. Blood pressure and heart rate in the ovine fetus: ontogenic changes and effects of fetal adrenalectomy. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H248–H256. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whorwood CB, Firth KM, Budge H, Symonds ME. Maternal undernutrition during early to midgestation programs tissue-specific alterations in the expression of the glucocorticoid receptor, 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoforms, and type 1 angiotensin ii receptor in neonatal sheep. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2854–2864. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoon JC, Puigserver P, Chen G, et al. Control of hepatic gluconeogenesis through the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Nature. 2001;413:131–138. doi: 10.1038/35093050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao R, Duncan SA. Embryonic development of the liver. Hepatology. 2005;41:956–967. doi: 10.1002/hep.20691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]